Imperial Japanese Navy

|

Imperial Japanese Navy |

|

|---|---|

Kyokujitsuki (flag) of the Imperial Japanese Navy. It was introduced in 1889 and consists of the Japanese national flag , supplemented with 16 stylized rays. |

|

| active | 1869 to 1945 |

| Country |

|

| Type | marine |

| management | |

| High command | General Staff |

| High command in case of war | Daihon'ei |

| administration | Department of the Navy |

The Imperial Japanese Navy ( Japanese 大 日本 帝國 海軍 Shinjitai : 大 日本 帝国 海軍 or 日本 海軍Nippon Kaigun ), literally the Navy of the Empire of Greater Japan, was the naval force of the Empire of Greater Japan . Its construction began in 1869 and it rose to become one of the strongest sea powers in the world , alongside the American US Navy and the British Royal Navy , by the Pacific War in 1941 . It was subordinate to an admiral staff and was administered by the Ministry of Navy . Alongside the Imperial Japanese Army (Army), it was one of two parts of the armed forces in the Japanese Empire that were commanded together by the Daihon'ei in times of war .

history

As early as the end of the 16th century, under the unification of the empire Toyotomi Hideyoshi, there was a first all-Japanese fleet, which was defeated by the Korean navy in the Imjin War . Until the first half of the 17th century, the Japanese built ocean-going ships based on western standards. But after the government ( Tokugawa Shogunate ) had decided on an isolation policy with the closure of Japan , the production of ocean-going ships was not pursued for almost two and a half centuries. However, the maritime tradition was maintained by the Satsuma clan, who played a key role in the newly formed Imperial Navy from the late 19th century.

Japanese fleets of the Middle Ages and early modern times

The island location of Japan allowed fishing and coastal shipping to flourish early on. The dugout canoes , bundle of reed rafts and bark boats had survived among the Ainu natives until the 20th century . The art of shipbuilding adopted by the Koreans and Chinese also made the Japanese into a sea people and enabled maritime traffic not only to China and Korea, but also via Formosa (Taiwan) to India and the Philippines. The predominant vehicle type was initially the frameless plank boat and the junk that emerged from it . As with Korean junks, the planks of the floor were laid lengthways (with Chinese junks they were transverse), while the stern and rudder resembled Chinese junks. The bow of Japanese junks, on the other hand, was more pointed and ended in a jib boom with staysail, to make turning and cruising easier, gaff and spriet sails based on the European model have often been introduced since the 19th century.

The first naval battles between the feudal families fighting for power took place as early as the 12th century. During the Gempei War , the Minamoto remained victorious in the naval battles of Yashima and Dan-no-ura in 1185 and henceforth ruled the entire country as shoguns . However, their maritime power was modest and, in view of the ever new outbreak of civil wars, was hardly in a position to take action against the rising piracy. At the beginning of the 13th century a new phase of intense maritime interactions between Japan, Korea and China began. While China and Korea ( Goryeo ) were busy with the expansion of the Mongols on land and had to raise gigantic tribute payments, their coastal defense and the naval force necessary to protect trade fell into disrepair. Japanese pirates, the Wokou , took advantage of this and, from 1223, plundered mainly Korean coastal cities and merchant ships. After the subjugation of China and Korea, the Mongols urged Japan to fight piracy. The Japanese rejection was ultimately a trigger for the Mongol invasions in Japan in 1274 and 1281 , mainly supported by Korean ships. The Japanese owed their successful defense against the invasions not to their warships, but to their land army and " divine storms "; After the defeat of the Mongols and the decline of their power, however, Japanese pirates began organized military attacks from 1302 on the Mongol-ruled China.

The Ming Dynasty , which came to power in China in 1368 after the expulsion of the Mongols, and the Joseon Dynasty , which came to power in Korea in 1392, strengthened the coastal defenses and created strong war fleets to protect merchant shipping and to combat Japanese pirates. After a Korean naval attack on the Tsushima pirate base , the Japanese pirate raids came to a temporary end from 1419. From the middle of the 15th century, however, China reduced its naval engagement, and coastal defense also fell into disrepair. Chinese smugglers joined the Japanese pirates. The simultaneous lack of a Japanese central authority ( Sengoko period ), which would have been able or at least willing to fight organized piracy, favored its resurgence. From the middle of the 16th century, the attacks along the navigable rivers into the Chinese hinterland reached a new high point. It was not until 1563 that the Chinese ( Qi Jiguang ) were able to inflict a devastating blow on the pirates.

In Japan, Oda Nobunaga was the first to end the piracy. For the fight against rival princes and pirates he had large, possibly iron- armored coastal defense ships ( Atakebune ) built in 1576 , for which he recruited the last pirates. His successor, the regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi, wanted to distract the samurai and professional warriors who were now unemployed after the unification of the empire with a campaign against China. Since Korea refused the Japanese to march through to China, Hideyoshi began the Imjin War against Korea in 1592 . From Kyushu Hideyoshi crossed over with hundreds of transport ships. The Korean armed forces had nothing to oppose the up to 200,000 war-experienced Japanese who had landed, but the Korean navy was superior to Hideyoshi's fleet and defeated them as early as 1592 in the sea battle of Okpo . The Korean fleet was smaller than the Japanese, but the Korean seamen were more experienced and battle-tested, and their turtle ships were stronger than the numerically superior Japanese transport ships. The temporary Japanese victory at Chilcheonryang in 1597 did nothing to change this. While the Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin defeated the Japanese transport fleet at Myongnyang in 1598 and thus cut off supplies, the Koreans managed to repel the Japanese on land with the help of Chinese troops.

Yi Sun-sin defeated the ships returning to Japan at the end of 1598 in the sea battle of Noryang, but even after this defeat and Hideyoshi's death, Japan initially remained a seafaring nation. Hundreds of Tokugawa - shogunate emitted Red Seal ships exaggerated at the beginning of the 17th century overseas trade to the Philippines, Indonesia and Indochina. There they met European ships and the first European influences on the Japanese art of shipbuilding. However, for fear of the prevailing European influences (e.g. Christian missionary work ), the shogunate ordered Japan to be sealed off in 1636 , overseas shipping was discontinued, and the building of ocean-going ships as well as Christianity were forbidden. From then on, a certain maritime tradition was only maintained by the Shimazu clan , who had subjugated the island of Okinawa and the entire kingdom of Ryūkyū from Satsuma (Kigoshima) in 1609 and who controlled the sea connections to the islands. Those descendants of the feudal lords of the region , later mostly known as the Satsuma clan, were to play a key role in the new Imperial Navy in the Meiji era from the end of the 19th century.

Time of opening

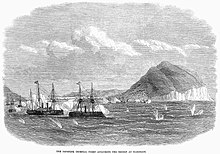

Only after the forced opening of the Japanese Empire by the USA after 1854 ( Kanagawa Convention ) and the bombardment of Shimonoseki and Kagoshima did the ruling class again see the need to modernize and bring the maritime defense up to date.

With the Meiji Restoration from 1868, the construction of the navy was pushed forward. A naval school was opened in Nagasaki in 1869, and future command officers were sent to study in western countries. The initial inventory of obsolete ships was taken over by the Shogunate Navy . During the reign of Emperor Mutsuhito in 1869, the Japanese acquired their first steel armored ship from the French, the Kōtetsu , formerly Stonewall , and other ships from France and Great Britain . The Imperial Navy passed its first baptism of fire in May 1869 in the naval battle of Hakodate against insurgent remnants of the old shogunate navy. After the end of this (first) civil war, in 1873 the Imperial Navy had 17 warships with 70 cannons and 2,300 men, including an armored corvette with 12 cannons, a wooden corvette with 10 cannons and six cannon boats with a total of 23 cannons. Their first mission against neighboring countries, a Japanese landing on Taiwan, failed in 1874 due to Chinese resistance. The next mission was more successful: In Korea, Japanese warships and Japanese gunboat policy forced the opening of three contract ports for Japanese trade in 1876 . After a second civil war and the suppression of the Satsuma rebellion in 1877 and the associated annexation of the Ryūkyū Islands in 1879, the Satsuma clan began to play a dominant role in the Imperial Navy, numerous admirals and naval ministers came from this old samurai family and their subsidiary lines (e.g. Saigō Tsugumichi , Yamamoto Gonnohyōe ). Their rivalry with the Chōshū clan , which dominated the army, influenced government policy from then on.

At the beginning of 1887 the Imperial Navy had a casemate ship , two belted armored cruisers, two armored ramming ships, four ramming cruisers, eight cruisers (three of them under construction), three second-class cruisers, two wheeled Avisos (one of which was used as a torpedo training ship ), seven gunboats (including one under construction), three screw steamers used as training ships, a screw yacht, a deep-sea torpedo boat, 19 torpedo boats and two torpedo launches. From 1886 to 1890, the French warship designer Louis-Émile Bertin developed the basic features of the Japanese naval plan, trained Japanese designers, and designed modern warships and bases.

In 1894, on the eve of the First Sino-Japanese War , the Japanese fleet had 58 warships with 497 guns, including one ironclad and 26 torpedo vehicles. The bulk of the combat-strong units that Japan had in its fleet had been bought abroad:

- Hiei , armored corvette, 2300 tons, completed in Great Britain in 1878

- Congo , armored corvette, 2300 tons, completed in Great Britain in 1878

- Fusō , ironclad, 3700 tons, completed in Great Britain in 1878

- Naniwa , armored cruiser, 3600 tons, completed in Great Britain in 1885

- Takachiho , armored cruiser, 3600 tons, completed in Great Britain in 1885

- Unebi , protected cruiser, 3615 tons, completed in France in 1886

- Chiyoda , armored cruiser, 2400 tons, completed in Great Britain in 1891

- Itsukushima , protected cruiser, 4200 tons, completed in France in 1891

- Matsushima , protected cruiser, 4200 tons, completed in France in 1892

- Yoshino , armored cruiser, 4150 tons, built in Great Britain in 1892

- Akitsushima , armored cruiser, 3100 tons, completed in Japan in 1894

- Hashidate , protected cruiser, 4200 tons, completed in Japan in 1894

Rise to sea power

The Imperial Japanese Navy then experienced its first major rehearsal in the First Sino-Japanese War. On September 17, 1894, the sea battle took place on the Yalu , in which the Japanese fleet sank eight of twelve Chinese warships.

The analysis of the battle led to important findings in shipbuilding. In particular, the heavy 32 cm guns of the Matsushima and her two sister ships of the Sankeikan class had disappointed, while their fast-firing 12 cm guns were attributed a decisive part in the victory.

After the end of the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the forced return of the Liadong Peninsula to China by Russia , Japan began to prepare for any further conflicts by building up a powerful army and fleet. To this end, Japan announced a 10-year plan to build up its naval forces. The core of the plan was the construction of the "six-six program" of six battleships and six armored cruisers as the core of the Japanese Navy. Since Japan was not yet able to build large armored ships, the orders went to foreign shipyards, mainly to Great Britain. Great Britain and Japan grew closer in their interests during this time, which eventually ended in the Anglo-Japanese Alliance . France, which initially had a strong influence on the development of the Japanese navy, and Germany seemed to want to expand their influence in East Asia from the Japanese point of view.

All six ships of the line were ordered in Great Britain. The two ships of the Fuji class , whose approval and contracting had already begun before the war, became the first ships in this construction program. Another three ships of the line were the Shikishima and Asahi , ordered in 1896 , and the Hatsuse, ordered in 1897 . These are referred to as the Shikishima class , with Asahi as a two-chimney differing from the other two three-chimneys, and is therefore often viewed as a single ship. The last ship of the line in this construction program was the better armored Mikasa , which was delivered in 1902 and served as the flagship of the fleet during the Russo-Japanese War .

The British company Armstrong supplied the marine artillery for all ships in the expansion program, two of the aforementioned ships of the line ( Yashima , Hatsuse ), the protected cruiser Takasago and the four armored cruisers Asama , Tokiwa , Izumo and Iwate , the first two and the last of which were sister ships. For political and diplomatic reasons, the Yakumo was ordered in Germany and her near-sister ship Azuma in France . The Yakumo was the only new build of the Japanese Navy that was commissioned in Germany. These two armored cruisers were also armed for compatibility with British guns.

When tensions with Russia increased from 1897 onwards, the Japanese navy acquired two Kasuga- class armored cruisers in Italy, which had been built there for Argentina and were on the transfer voyage in Singapore when the war broke out .

Japanese self-builds were largely limited to protected cruisers , destroyers and gunboats . Between the war with China and the war with Russia, eight new cruisers came into service with the Japanese fleet, five of which (two of the Suma class , two of the Niitaka class and the Otowa ) were built in Japan, while the Kasagi and the Chitose were built the USA and the Takasago from Great Britain.

In 1900 the Japanese Navy participated in the fight against the Boxer Rebellion in China on the part of the Western powers. It provided the largest number of Allied warships (18 of the initial 50 ships) and the largest contingent of troops (20,840 soldiers from the army and navy with a total of 54,000 men). The cooperation with the European powers and the USA gave the Japanese military insights into their methods, procedures and decision-making bases.

The next major conflict was the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/05. Major naval maneuvers had taken place as early as the spring of 1903. On the eve of the war, the war fleet counted 7 ships of the line of 93,712 tons (including the largest, Mikasa, launched in 1900, 15,440 tons, 19 nautical miles an hour, 16,400 horsepower, 4 heavy 30.5 cm, 14 medium, 32 light rapid-loading cannons, 4 torpedo tubes), 1 armored cannon boat, 6 armored cruisers of 58,778 tons (the largest, Iwate, launched 1900, 9,906 tons, 21 nautical miles an hour, 14,700 hp, 4 heavy, 14 medium, 20 light rapid-loading cannons, 4 torpedo tubes), 16 protected cruiser of 59,529 tons (the largest, Kasagi, launched in 1898, 4,978 tons, 22.5 nautical miles per hour, 17,235 hp, 2 heavy, 10 medium, 18 light rapid-loading cannons, 5 torpedo tubes), also 3 Avisos, 2 gunboats, 21 torpedo vehicles from 203–864 tons, 57 torpedo boats from 80–152 tons. 60 Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha steamers were on duty as auxiliary cruisers. After the Japanese fleet had switched off the Russian Pacific fleet in the port of Port Arthur in a surprise attack in February 1904, it also succeeded in defeating the outnumbered Russian Baltic fleet in the naval battle of Tsushima in May 1905 . The Russian fleet was almost completely destroyed and lost 34 of 38 ships. The result of the battle was the end of the war and a shift in the consciousness of Japanese naval planners. From now on, a strategy of the "great decisive battle" was used and other possible courses of a conflict began to be largely neglected in planning considerations.

Shortly before the outbreak of war with Russia, Japan ordered two ships of the line similar to the British King Edward VII class in Great Britain. Construction of the Katori class began before the loss of the Yashima and Hatsuse and was not a response to those losses, as is often shown. It was only during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 that the Japanese Navy ordered the Satsuma-class battleships , the Satsuma and Aki , in Japan, which began in Yokosuka and Kure in 1905 . These four ships with reinforced medium artillery were followed by the first Japanese " dreadnoughts " with the two ships of the Kawachi class , Kawachi and Settsu . They were the first ships of a new eight / eight program (8 battleships and 8 battle cruisers). Also during the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese Navy ordered six Tsukuba-class armored cruisers in response to the loss of the aforementioned ships of the line. They should get the same heavy artillery and have the speed of an armored cruiser. In fact, only two ships of this class were completed. Two similar reinforced armored cruisers came into service as the Ibuki class before the first real battle cruisers. These four heavy armored cruisers were reclassified as the first battle cruisers in 1912 .

Armament

After defeating China and Russia and most European states suffered heavy losses in ships and industrial capacities in World War I , Japan rose to become the third strongest sea power in the world after England and the USA around 1920.

The United States had by its annexation of Hawaii in 1898 and occupation of the Philippines in 1899 and developed a regional power in the Pacific and stood in economic competition with Japan. The subsequent interference by the USA in Japan's China policy through the proclamation of the “ open door policy ” from 1899 onwards intensified tensions. A future exchange of blows against the numerically superior enemy USA therefore seemed the most likely early on to the Japanese naval planners.

In order to compensate for their quantitative inferiority, the Japanese Navy relied on increasing quality and a high degree of specialization when planning new ships and training their crews. The smaller number of heavy units that the Navy had at its disposal should first be compensated for by decimating the potential opponent's fleet through surprise attacks to such an extent that their remnants could be defeated in a major decisive battle. Even without the technical possibilities of radar , attacks at night, in which the darkness helped to mask one's own weakness, or by submarines appeared as a suitable means of achieving this goal.

Japan's heavy and light cruisers, destroyers and submarines were developed specifically for this task in the period that followed. A high level of training of officers and men, in which value was placed on the night combat capabilities of entire naval units, should help to implement the strategy , together with the development of appropriate weapons, such as powerful torpedoes .

This determination led to technical developments that made Japan superior to all other sea powers in these areas. Other areas that would be important in an unexpectedly long naval war, such as protecting merchant ships and fighting enemy submarines, were largely ignored.

Sustainably prevented by the London Agreement from building new battleships , the Japanese concentrated on cruisers and destroyers , but also built an aircraft carrier fleet and the associated aviation industry.

Shipbuilding 1912–1945

A key element in the doctrine of the great decisive battle were surface units with heavy artillery . The navy initially asked for eight battleships and eight battle cruisers , the construction of which was to begin before the First World War. The only ship commissioned abroad was the battle cruiser Kongō in 1913 , which was laid down by the Vickers shipyard in Great Britain. The navy could not convince the politicians to provide the funds for the construction of all required ships, so the battleship building dragged on until the Second World War. Of the units that had started, the construction of the Tosa class and the Amagi class had to be stopped due to international fleet contracts and the Tosa , which had already been launched, had to be destroyed. The second Tosa-class ship and one Amagi-class ship were converted into aircraft carriers.

Capital ships

Battleships

- Fusō class , 2 ships, construction started in 1912

- Ise class , 2 ships, construction started in 1915

- Nagato class , 2 ships, construction started in 1917

- Tosa class , 2 ships, construction started in 1922 (canceled)

- Yamato class , 5 ships, construction started in 1937 (2 deleted)

Battle cruiser

- Kongō-class , 4 ships, construction started in 1911

- Amagi class , 4 ships, construction began in 1920 (canceled)

Aircraft carrier

Fleet aircraft carrier

The realization that aircraft carriers would play a key role in future conflicts only slowly penetrated the ranks of naval planners from 1920 onwards. In 1928, the first carrier division was formed with the three existing carriers and a corresponding, independent doctrine began to be developed. Only when the beginning of the Second World War began to emerge did the Navy begin to develop massive construction activity in the aircraft carrier sector, largely discontinued other construction programs and began converting (*) other types of ships into aircraft carriers.

- Hōshō , 1 ship, construction started in 1919

- Kaga , 1 ship, construction started in 1920 *

- Akagi , 1 ship, construction started in 1920 *

- Sōryū class , 2 ships, construction started in 1934

- Shōkaku class , 2 ships, construction started in 1937

- Hiyō class , 2 ships, construction started in 1939

- Shinano , 1 ship, construction started in 1940 *

- Taihō , 1 ship, construction started in 1941

- Unryū class , 6 ships, construction started in 1943

Light aircraft carrier

- Ryūjō , 1 ship, construction started in 1929

- Zuihō class , 2 ships, construction started in 1934 *

- Ryūhō , 1 ship, construction started in 1941 *

- Chitose class , 2 ships, construction started in 1943 *

- Ibuki , 1 ship, construction started in 1943 *

Escort

- Taiyō class , 3 ships, construction started in 1938 *

- Kaiyo , 1 ship, construction started in 1942 *

- Shin'yō , 1 ship, construction started in 1942 *

cruiser

Heavy cruisers

The so-called A-class cruisers were an important part of the fleet . These heavy cruisers made full use of the contractually permitted limits and in some cases even exceeded them considerably. Designed with the basic idea of using them in quick, surprising attacks at night, their artillery and torpedo armament formed the heaviest cruiser armament in international comparison. From 1922 the Navy built six classes of heavy cruisers, the seventh was discontinued:

- Furutaka class , 2 ships, construction started in 1922

- Myōkō-class , 4 ships, construction started in 1924

- Aoba class , 2 ships, construction started in 1926

- Takao class , 4 ships, construction started in 1927

- Mogami class , 4 ships, construction started in 1931

- Tone class , 2 ships, construction started in 1934

- Ibuki class , 2 ships, construction started in 1942 (canceled)

Light cruisers

From the findings of the First World War, the navy derived the need for ships with the combat power of a destroyer, but which should have a greater range and better communication options. The requirements increased with heavy torpedo armament and later also with anti-submarine capabilities.

- Tenryū class , 2 ships, construction started in 1917

- Kuma class , 5 ships, construction started in 1918

- Nagara class , 6 ships, construction started in 1922

- Sendai-class , 3 ships, construction started in 1922

- Yūbari , 1 ship, construction started in 1922

- Katori class , 4 ships, construction started in 1938 (1 deleted)

- Agano class , 4 ships, construction started in 1939

- Ōyodo , 1 ship, construction started in 1941

destroyer

Destroyers had become the workhorse of the navies and the Japanese navy initially invested extensively in the development of their destroyer fleet, but neglected its continuous modernization, so that the majority of its flotilla was out of date at the beginning of the Pacific War in 1941 or was about to end its service life. The neglect of the destroyer construction and the specialization of the ship classes in the fight against surface ships, in combination with inadequate retrofitting of the existing units with modern radar and anti-submarine equipment, proved to be devastating for Japanese merchant shipping in the Pacific War.

- Sakura class , 2 ships, construction started in 1912

- Urakaze class , 2 ships, construction started in 1913

- Kaba class , 10 ships, construction started in 1915

- Momo class , 4 ships, construction started in 1916

- Isokaze class , 4 ships, construction started in 1916

- Kawakaze class , 2 ships, construction started in 1916

- Enoki class , 6 ships, construction started in 1917

- Minekaze class , 15 ships, construction started in 1918

- Momi class , 21 ships, construction started in 1919

- Kamikaze class , 9 ships, construction started in 1921

- Wakatake class , 8 ships, construction started in 1921

- Mutsuki class , 12 ships, construction started in 1924

- Fubuki class , 20 ships, construction started in 1926

- Akatsuki class , 4 ships, construction started in 1930

- Hatsuharu class , 6 ships, construction started in 1931

- Shiratsuyu-class , 10 ships, construction started in 1933

- Asashio-class , 10 ships, construction started in 1935

- Kagerō-class , 19 ships, construction started in 1937

- Yūgumo class , 19 ships, construction started in 1940

- Akizuki-class , 12 ships, construction started in 1940

- Shimakaze class, 1 ship, construction started in 1941

- Matsu class , 18 ships, construction started in 1943

- Tachibana class , 14 ships, construction started in 1944

Torpedo boats

- Chidori class , 4 ships, construction started in 1931

- Otori class , 8 ships, construction started in 1934

Kaibokan

Kaibokan (Japanese 海防 艦) (Kai = ocean, Bo = defense, Kan = ship, ocean defense ship) were security ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy which were built in Japan from 1939 to 1945 in various shipyards. Six different Kaibokan classes were built. First, the Shimushu class or class A was built. On December 13, 1939, construction began on the Shimushu, the first ship of the Kaibokan class of the same name. 171 Kaibokan ships had been completed by the end of the war. Furthermore, in June 1944, the Isojima , the captured Chinese light cruiser Ning Hai , and the Yasojima , the captured Chinese light cruiser Ping Hai , were put into service as Kaibokan. Of the 173 Kaibokan, only 68 were still operational at the end of the war. The other ships were mostly sunk by attacks by Allied submarines and aircraft. The Shimushu-class ships were built to act as security ships for convoys, anti-mine vehicles and fishing protection boats. The later classes were only built as security ships for convoys. The main task in the convoy was anti-submarine and anti-aircraft defense.

- Shimushu class , 4 ships, construction started in 1938

- Etorofu class , 14 ships, construction started in 1942

- Mikura class , 8 ships, construction started in 1942

- Ukura class , 31 ships, construction started in 1943

- C-Class , 56 ships, construction started in 1943

- D-class , 67 ships, construction started in 1943

Submarines

The Imperial Japanese Navy began importing and inspecting various foreign submarine designs prior to World War I. Samples of the American Holland class , the British C and L class , the French Laubeuf type and the Italian Fiat Laurenti type were purchased. Seven formerly German submarines fell to Japan after the war in 1919 and were extensively tested. To this end, German specialists were recruited to train Japanese designers and strategists. The submarine structures that followed were largely seen as support units for the regular fleet and in some cases had properties such as high speed and the ability to carry a reconnaissance aircraft that appeared helpful for this role. Unlike other naval forces of the time, the Japanese Navy developed a very wide variety of submarine types.

The submarines delivered after the First World War were:

| boat | Type | displacement | Japanese identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| SM U 125 | UE2 | 1164/1512 tons | until 1921 as O1 |

| SM U 46 | U Ms | 725/940 t | until 1921 as O2 |

| SM U 55 | U Ms | 715/902 tons | until 1921 as O3 |

| SM UC 90 | UC III | 474/560 t | until 1921 as O4 |

| SM UC 99 | UC III | 474/560 t | until 1921 as O5 |

| SM UB 125 | UB III | 516/651 t | until 1921 as O6 |

| SM UB 143 | UB III | 516/651 t | until 1921 as O7 |

Kaidai class

- Type KD1, a boat

- Type KD2, two boats

- Type KD3a, four boats

- Type KD3b, three boats

- Type KD4, three boats

- Type KD5, three boats

- Type KD6a, six boats

- Type KD6b, two boats

- Type KD7, ten boats

Junsen class

- Type J1, four boats

- Type J1 Mod., A boat (with two reconnaissance planes)

- Type J2, a boat

- Type J3, two boats (each with a reconnaissance aircraft)

A class

- Type A1, three boats (each with a reconnaissance aircraft)

- Type A2, a boat (each with a reconnaissance aircraft)

- Type AM , two boats (each with two dive bombers)

B class

- Type B1, twenty boats (each with a reconnaissance aircraft)

- Type B2, six boats (each with a reconnaissance aircraft)

- Type B3, three boats (each with a reconnaissance aircraft)

C class

- Type C1, five boats

- Type C2, three boats

- Type C3, three boats

D class

- Type D1, eleven boats

- Type D2, a boat

Kirai-sen class , four

Sen-Ho-class boats , one

Sen-Toku-class boat , three boats (each with three dive bombers)

Sen-Taka-class , three boats

Anti-mine vehicles

- W-1 class , 6 ships, construction started in 1922

- W-13 class , 6 ships, construction started in 1931

- W-7 class , 6 ships, construction started in 1937

- W-19 class , 17 ships, construction started in 1940

- Wa-1 class , 22 ships, construction started in 1941

Mine layers and net layers

- Katsuriki , 1 ship, construction started in 1916

- Shirataka , 1 ship, construction started in 1927

- Itsukushima , 1 ship, construction started in 1928

- Sokuten class , 13 ships, construction started in 1911

- Tsubame class , 2 ships, construction started in 1928

- Yaeyama , 1 ship, construction started in 1930

- Natsushima class , 2 ships, construction started in 1931

- Okinoshima , 1 ship, construction started in 1934

- MV Tenyo Maru , 1 ship, construction started in 1934

- Hatsutaka class , 3 ships, construction started in 1938

- Tsugaru , 1 ship, construction started in 1939

- Minoo , 1 ship, construction started in 1944

- Kamishima class , 2 ships, construction started in 1945

Seaplane carriers and tenders

- Notoro class 1 ship, construction started in 1919

- Kamoi 1 ship, construction started in 1921

- Kamikawa Maru class 4 ships, construction started in 1937

- Mizuhō 1 ship, construction started in 1937

- Nisshin 1 ship, construction started in 1938

- Akitsushima 1 ship, construction started in 1940

Auxiliary ships

- Asahi Maru 1 hospital ship

- Yasukuni Maru 1 submarine support ship, construction started in 1929

- Akashi 1 workshop ship, construction started in 1937

- Kazahaya 1 fleet tanker, construction started in 1942

- Hakachi 1 target ship, construction started in 1943

- Ōhama 1 target ship, construction started in 1944

Small weapons

In order to protect its island bases and the Japanese home islands in the event of impending invasions , the navy initiated several projects to build so-called small weapons until the end of the war . The programs included several types of miniature submarines , such as the " little fly ", the experimental submarine class type A and type A . There were also various types of the manned torpedo Kaiten and explosive devices of the Shin'yō type . However, the successes of these weapons were modest or they came too late to influence the course of the war.

Other extreme means, such as the use of the Fukuryō , a unit of divers who were supposed to sacrifice themselves in the defense against enemy dropships, were prepared to a small extent, but were no longer used.

staff

The Japanese Navy began to restructure its training program around 1900. Based on its own studies and observations abroad, the Naval Academy introduced a course system that consisted of a two-year course for prospective staff officers and a six-month course for junior officers. The graduates of the semi-annual course were then assigned to specialization schools of the Navy to learn navigation, fire control, torpedo shooting and other technical disciplines. Due to the practice of only training candidates to become naval officers when the Navy actually had a need for new officers, the number of graduates from the Navy Academy was too low to keep up with the growing number of ships in the Navy. With an estimated ten years of training and service required for a competent lieutenant and 20 years for a skilled commanding officer, the practice of not starting training additional officers until a new ship was commissioned was not more contemporary. Although it was possible to maintain a high level of training in the selection of the few admitted candidates, it was not possible to build up any significant reserves that were urgently needed in the war. In particular, the low staffing levels in the Navy Air Force should prove to be a problem with the heavy losses in the Pacific War that could never be solved satisfactorily.

Ground forces

The Imperial Japanese Navy had extensive ground forces ( Japanese 海軍 陸 戦 隊 , Kaigun riku sentai ) inside and outside the Japanese Empire. As early as 1870, they set up the Japanese Marine Infantry , which consisted of infantry and artillery units. From 1929 onwards, there was a regrouping and the associated establishment of units or departments for operational use in amphibious landings, supporting parachute missions in enemy territory, anti-aircraft defense, guarding naval bases and naval facilities, pioneering and communications services, military police and civil engineering departments. The most famous units to emerge from the Imperial Japanese Navy's ground forces were the Navy's Special Landing Forces (including naval paratroopers ), which participated in numerous missions during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War.

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War was the first emergency for the Japanese Navy. This was clearly superior to its Chinese opponents in terms of material and equipment and was able to achieve a clear victory over the Chinese fleet in the sea battle at Yalu on September 17, 1894.

Russo-Japanese War

In the Russo-Japanese War, it was the Japanese fleet that opened combat operations. On the night of February 8th to 9th, 1904, Japanese destroyers attacked the Russian Pacific fleet off Port Arthur in a surprise attack . Although only three of the 16 torpedoes fired detonated, three ships of the line were immobilized. It was not until February 10, 1904 that the Japanese Empire officially declared war on the Russian Empire . Then there were the sea battles at Chemulpo , in the Yellow Sea , Ulsan and Korsakow , all of which ended victorious for the Japanese.

From May 27 to May 28, 1905, the decisive naval battle at Tsushima occurred , in which the Japanese defeated the Second Russian Pacific Squadron . Of 32 Russian ships, 28 were sunk or had to surrender.

First World War

The Imperial Japanese Navy took part in only a few combat operations during World War I. It is worth mentioning the siege of the German base in Qingdao , during which it carried out numerous operations to block the port and to transport Japanese troops. The Japanese losses were limited to the protected cruiser Takachiho and a few smaller units. In the further course of the war, Japanese troops occupied the German bases on the Marianas , Carolines and the Marshall Islands .

To relieve its own fleet, Britain asked Japan to send cruisers and destroyers. They were mainly used for escort duties in the Mediterranean and patrol services at the Cape of Good Hope , with the destroyer Sakaki being torpedoed on June 11, 1917 by the Austro-Hungarian submarine U-27 off Crete near the small island of Cengotto and badly damaged on the front ship. 59 men of the 92-man crew, most of whom were in the crew mess near the bow, were killed.

Second World War

The oil embargo against Japan of July 1940 and the growing economic pressure in the following period, not least due to pressure from the Imperial Navy, finally led Japanese politicians to realize that a military conflict with the USA could not be avoided.

The leadership of the Japanese Navy was aware that they would not be able to wage a longer war against the Allies in the Pacific. After France, the Netherlands and Great Britain were weakened by military losses in the European theater of war and could no longer defend their possessions in the Pacific region, the Japanese planners took the opportunity and prepared the landing of Japanese troops in the region. The armed conflict began with a surprise attack in December 1941 on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor by Japanese carrier aircraft, which was promptly followed by landing operations throughout the Pacific region. With the oil fields occupied in the Dutch East Indies , the fuel shortage was initially compensated for. With well-rehearsed crews, their modern cruiser and aircraft carrier fleet and their excellent night combat capabilities, the Imperial Navy succeeded in inflicting heavy losses on the Royal Navy, the Dutch, Australians and Americans in the early stages of the war.

After the hoped-for peace agreement with the USA did not materialize, the German Empire was forced to further expand its area of influence in the Pacific after the Doolittle Raid . In June 1942, in the Battle of Midway and in the ensuing battles for the island of Guadalcanal , the Imperial Navy suffered heavy losses in ships, aircraft and personnel that it could no longer make up for. At the same time, the number of Japanese cargo ships and tankers sunk by American submarines rose rapidly, while the Imperial Navy lacked the numerical strength and the technical means to counter this threat. Of the 6.6 million tons of available transport capacity at the beginning of the Pacific War, 1.8 million were used for naval operations and 2.1 million for transports for the Imperial Japanese Army. As early as 1942, the Allied submarines succeeded in sinking more ship space than the Japanese shipyards were able to build.

The lack of powerful Japanese radars and the intrusion of American interception specialists into Japanese naval communications gave the other side an information advantage on a tactical and strategic level, which increasingly turned the tide in favor of the Americans in combat.

The End

Unable to protect their merchant shipping, to compensate for the losses of their own ships by building new ones, to absorb the losses of highly qualified personnel and to catch up with the technical progress of the Americans, the Imperial Japanese Navy got more and more on the defensive in the Pacific War. The last major decisive battle in the Philippines, for which the naval planners used the majority of the ships still in existence, led to the sea and air battle in the Gulf of Leyte in October 1944 , in which a considerable number of the ships of the Imperial Navy were lost. The remnants of the fleet were no longer to play a decisive role until the end of the war.

After the end of the war, Japan undertook not to set up any more navies. As part of its self-defense forces , however , Japan set up the sea self-defense forces , which are defensive and have only taken over the flag of the Imperial Navy.

See also

- Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force

- Japanese Empire

- Imperial Japanese Army

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Type designations of the Imperial Japanese naval aviators

literature

- Hugh Cortazzi, Gordon Daniels (Eds.): Britain and Japan 1859–1991. Themes and personalities. Routledge, London a. a. 1991, ISBN 0-415-05966-6 .

- Ian C. Dear, Michael Richard Daniell Foot (Eds.): The Oxford companion to World War II. Oxford University Press, Oxford a. a. 2001, ISBN 0-19-860446-7 .

- Manfred P. Emmes: The foreign policies of the USA, Japan and Germany in mutual influence from the middle of the 19th to the end of the 20th century (= studies on political science. Department: B, 91). Lit, Münster u. a. 2000, ISBN 3-8258-4595-8 .

- David C. Evans, Mark R. Peattie: Kaigun. Strategy, tactics, and technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941. US Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD 1997, ISBN 0-87021-192-7 .

- Norman Friedman: Seapower as strategy. Navies and national interests. US Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD 2001, ISBN 1-55750-291-9 .

- Cynthia Clark Northrup (Ed.): The American economy. A historical encyclopedia. Volume 1. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara CA u. a. 2003, ISBN 1-57607-866-3 .

- Phillips Payson O'Brien (Ed.): Technology and Naval Combat in the Twentieth Century and beyond (= Cass Series: Naval Policy and History. Vol. 13). Cass, London et al. a. 2001, ISBN 0-7146-5125-7 .

- J. Charles Schencking: Making waves. Politics, Propaganda, and the Emergence of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868-1922. Stanford University Press, Stanford CA 2005, ISBN 0-8047-4977-9 .

- Spencer C. Tucker , Laura Matysek Wood, Justin D. Murphy (Eds.): The European powers in the First World War. An encyclopedia (= Garland Reference Library of the Humanities 1483). Garland, New York NY et al. a. 1996, ISBN 0-8153-0399-8 .

- HP Willmott: The Last Century of Sea Power. Volume 1: From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894-1922. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. a. 2009, ISBN 978-0-253-35214-9 .

Web links

- Imperial Japanese Navy Page (combinedfleet.com )

- Imperial Japanese Navy (Nihon Kaigun) on worldwar2database.com (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Roger Goodman, Ian Neary: Case studies on human rights in Japan . Routledge 1996, ISBN 1-873410-35-2 , pp. 77 ff.

- ↑ Christopher P. Hood: Japanese Education Reform: Nakasone's Legacy . Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-203-39852-1 , p. 65.

- ↑ Hans Nevermann: The shipping of exotic peoples , page 15f. Wigankow, Berlin 1949.

- ^ Hermann Kinder, Werner Hilgemann: dtv-Atlas zur Weltgeschichte , Volume 1 (From the Beginnings to the French Revolution), page 227. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1990.

- ↑ Mathias Haydt: East Asia PLOETZ - History of China, Japan and Korea for reference , pages 39, 116f and 148. Ploetz Verlag, Freiburg / Würzburg 1986.

- ↑ a b Hermann Kinder, Werner Hilgemann: dtv-Atlas zur Weltgeschichte , Volume 2 (From the French Revolution to the Present), page 115. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1990

- ↑ a b Golo Mann (Ed.): Propylaea World History , Volume 9 (The Twentieth Century), Page 238f. Propylaea Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt 1986.

- ^ Meyers Konversations-Lexikon , Volume 9 (Japan), page 495. Third edition, Leipzig 1876

- ↑ Brockhaus' Conversations-Lexikon , supplement volume, page 452f. Leipzig 1887

- ^ Meyers Konversations-Lexikon , Ninth Volume (Japan), page 496. Fifth edition, Leipzig and Vienna 1897.

- ^ Stanley Sandler: Ground warfare: an international encyclopedia , p. 117, Arthur J. Alexander: The arc of Japan's economic development , p. 44.

- ^ Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon, Volume 10, page 183 . Leipzig 1905-07

- ^ A b Kaigun, Strategy, Tactics and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1877-1941, Naval Institute Press, 1997, ISBN 0-87021-192-7

- ↑ JAPANESE NAVY by Jon Parshall, viewed on August 2, 2009 ( Memento from December 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Phillips Payson O'Brien, 2001, Technology and Naval Combat in the Twentieth Century and Beyond, page 103

- ^ Willmott, 2009, The Last Century of Sea Power: From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894–1922, p. 449

- ↑ KAIBOKAN! Stories and Battle Histories of the IJN's Escorts

- ^ Carl Boyd: The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II , 2002, US Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-55750-015-1

- ^ Spencer Tucker, Laura Matysek Wood, 1996, The European powers in the First World War: an encyclopedia , 581

- ^ Spencer Tucker, Laura Matysek Wood, 1996, The European powers in the First World War: an encyclopedia , 655

- ^ Hugh Cortazzi, Gordon Daniels, 1991, Britain and Japan, 1859-1991: themes and personalities , 205

- ↑ Manfred P. Emmes, 2000, The foreign policies of the USA, Japans a. Germany in mutual influence from the middle of the 19th to the end of the 20th century page 51

- ^ Cynthia Clark Northrup, 2003, The American economy: a historical encyclopedia, Volume 1, p. 313

- ↑ Dear, Foot, 2002, The Oxford companion to World War II , p. 492

- ^ Norman Friedman, 2001, Seapower as strategy: navies and national interests, page 304