Karl Emil French

Karl Emil Franzos (born October 25, 1848 in Podolia , Russian Empire , crossed the border to his hometown Czortkow (today Tschortkiw ), Austrian Empire ; died January 28, 1904 in Berlin ) was an Austrian writer and publicist who was very popular at the time . His stories and novels reflect the world of Eastern European Judaism and the tensions to which he was exposed as a German and a Jew.

Life

The paternal ancestors were Sephardi , who came to Galicia via Lorraine in the 18th century under the name Levert . There they took the surname Franzos. Karl Emil Franzos' parents were the doctor Heinrich Franzos (1808-1858) and Karoline Franzos born. Klarfeld from Odessa . The father, strongly influenced by the ideas of German liberalism, felt and confessed himself to be German. As a district doctor in Tschortkau threatened by the Poles during the Wielkopolska Uprising , shortly before the delivery he sent his wife across the border to the family of a forester friend of his in the Russian governorate of Podolia . Shortly after the delivery, mother and son returned to Czortków across the border. In many books, however, Czortkow is given as the place of birth. Since Franzos himself writes in great detail about his birth outside of Czortków, this is probably a mistake.

Karl Emil Franzos received private lessons from Heinrich Wild, a participant in the Vienna October Uprising in 1848 , who was sent to the military as punishment. He later attended the Dominican convent school in Czortków for three years and also received private lessons in Hebrew. After the death of her father (1858) Karoline Franzos moved with her family to Chernivtsi , the capital of Bukovina . As ordered by his father in his will, Franzos attended the German kk I. Staatsgymnasium Czernowitz from 1859 to 1867 . Under the direction of Stephan Wolf , this only German middle school in the east enjoyed a high reputation. For the French, it was the “forecourt to paradise Germany”. He always remained top of the class and became more and more enthusiastic about German culture. In Chernivtsi he received the strongest impressions of his life. The insight into the ethnic complexity of the Habsburg Monarchy was reflected in the later stories and novels . The first poetic attempts also fall during school days. Franzos began to lean towards the profession of writer.

“The [Czernowitz] grammar school remained an ideal of German education and tolerance for him throughout his life. During the holidays he used the opportunity to gain an insight into the world of the ghetto of the Galician villages, and as much as he was attracted by the mysterious and poetic character of this almost archaic world of the shtetl , he was equally irritated by the intolerance of Hasidism , the deeply religious movement of the Eastern European Judaism. Despite the Mosaic religion of his family, to which he confidently adhered all his life, he had not been interested in the Judaism of the Chernivtsi community surrounding him since childhood. "

Academic years

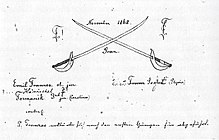

He passed his Matura on August 3, 1867 with distinction. At the end of the year he traveled to Vienna. On January 25, 1868 , he enrolled at the University of Vienna for law . This was preceded by an attempt to obtain a state scholarship to study classical philology . He was allegedly refused because he was Jewish and did not want to understand the hint to be baptized. Barely 19 years old, he was completely on his own two feet. He had a meager livelihood with lessons and small literary work. His fellow students included Hubert Janitschek , Alfred Klaar and Anton Schlossar . He was in the Academic Reading Club with the older Karl Lueger . On April 22, 1868 he became a fox of the Vienna academic fraternity of Teutonia . He was born on May 27, 1868. He was a member of the fraternity for 17 years . With the growing German national movement and its anti-Semitism (until 1945) he was expelled in 1885 with nine federal brothers.

For unknown reasons, Franzos finished his studies in Vienna in the summer semester of 1868. After spending the semester break at home in Czernowitz, he switched to the University of Graz for the winter semester of 1868/69 - probably in the hope of an easier livelihood. He immediately became active in the "Orion" academic association . He was Propräses in WS 1869/70 and President of the progressist federation in WS 1870/71 . He remained loyal to Orion until the end of his life.

The only major examination he passed on July 29, 1869, was the state examination in law and history. Franzos got in touch with Wilhelm Scherer , Julius Froebel and Robert Hamerling . He gave speeches at popular assemblies of the German National, signed the appeal to German universities of July 25, 1870, and played a prominent role in the charity event held on October 6, 1870 for the widows and orphans of the fallen German warriors. The fact that he was in charge of a German national Kommers on December 5, 1870 , he had to pay a fine after he had endured police harassment in 1868. He enthusiastically welcomed the proclamation of the German Empire . He spoke out in favor of a German unification under Prussian leadership, including Austria. He sat on the committee of the Victory Festival on March 6, 1871. His speeches and declamations had an extraordinary effect, for example in 1869 at the celebration of the 100th birthday of Alexander von Humboldt in Chernivtsi and at the commemoration of Ernst Moritz Arndt in Graz. Graz is the site of many of his stories and the setting of his only verse novella Mein Franz . In Graz he wrote satires , reviews , stories and poems for daily newspapers . The broken love affair with a Christian from Chernivtsi became the occasion for the novella The Christ Image . It was included in Westermann's monthly magazine and immediately met with approval from the readers. Franzos received a doctorate in law , but soon realized that he was more drawn to journalism and writing .

Half-Asia and everyday Jewish life

In 1872/73, Franzos wrote for the features section of Pester Lloyd . For the Neue Freie Presse he reported on the opening of the University of Strasbourg in the realm of Alsace-Lorraine , convinced “that the glorious German spirit, which has led to the proudest victories reported in history, will prove itself doubly proud and strong in peace will". Returning to Graz from Strasbourg in May 1872, he was determined to give up legal practice and devote himself to writing. The founding and editing of the weekly Die Laterne turned into a financial fiasco; It did not get past six issues. Travels to Venice , Genoa , Monaco , Florence , Rome and Naples were included in his travel articles.

Since his travel articles were popular, the Neue Freie Presse sent him from 1874 to 1876 on trips to the eastern part of the Habsburg Monarchy , the countries of the Hungarian Crown and Bukovina . He reported on the opening of the University of Chernivtsi . At the Kommers on October 5, 1875, a French celebratory song was sung. The cultural-historical and ethnographic newspaper reports appeared as a book under the title From Half-Asia . Updated again and again, several editions were very successful. In 1878 and 1888 further collections of such cultural images appeared ( Vom Don zur Donau , Aus der große Ebene ). Salomon Wininger wrote about the "ethnographic" writings of the French

“No other German-language poet like Franzos has accentuated the poetry of that half or completely barbaric subject area with such creative power. Next to him all the other actors of Jewish popular life disappear. "

The Jews wanted Franzos to adapt more to “German culture”, which earned him attacks from Jewish newspapers. He justified himself by saying that he was the first Jew to draw the Jews realistically and without any whitewashing. In the short story collection Die Juden von Barnow (1877), which unites Jewish Stetl stories, Franzos erected a literary monument to his hometown of Czortkow (the fictional Barnow of his writings). These works created the material basis for him to turn more and more away from daily journalism and devote himself to writing in his main profession.

marriage

During his summer vacation in Gmunden in 1876 , he met Ottilie Benedikt. As the daughter of a Jewish businessman, she was related to the co-editor of the Neue Freie Presse Moriz Benedikt and the writer Fritz Mauthner . She had published texts under the name “Fanny Ottmer”. On January 28, 1877, she married Franzos in the Vienna City Temple . Her brother was the lawyer and politician Edmund Benedikt , who later became historian Heinrich Benedikt, her nephew.

Publisher in Vienna

In addition to his work as a writer, Franzos also worked as a translator, for example of Gogol and Ukrainian folk songs, and above all as an editor. In 1879, Franzos published the works of Georg Büchner , the increasingly forgotten German poet from the pre- March period , as an outstanding achievement . In addition to the well-known theater plays Dantons Tod and Leonce and Lena , this edition also contained the Woyzeck (then still Wozzeck ), the French from the estate first published in 1878 in the magazine Mehr Licht! published. Franzos' edition is rated positively in contemporary philology, on the one hand, and editing errors and the partial destruction of Büchner's manuscripts by Franzos are criticized on the other. According to Kindler's literary dictionary, Woyzeck is the original spelling. "Wozzeck" can be traced back to a typo by Franzos, which was taken over in Alban Berg's opera "Wozzeck".

In 1884, Franzos became editor of the Neue Illustrierte Zeitung in Vienna and in 1886 founded the magazine Deutsche Dichtung (1886–1904), which he edited until his death. Conrad Ferdinand Meyer , Theodor Fontane and Theodor Storm wrote in this literary journal . Franzos also made it his business to promote young talent. Stefan Zweig published his first poems and aphorisms in it. During his ten years in Vienna, Franzos was one of the friends, confidants and advisers of Rudolf of Austria-Hungary . He also advised him on the Crown Prince Work .

Berlin

In 1887, Franzos left his journalistic life behind. He moved with his wife from Vienna to Berlin. There he wrote mostly bourgeois love and social novels with slightly pessimistic features, which despite some echo from the reading public did not become literary canonical. At the same time he got involved with his fellow Jews in Russia, who were under increasing pressure. In 1891 he joined the Central Committee for Russian Jews , which raised money for persecuted Jews. He also gave lectures on this topic (manuscript titles: Russian literature and culture , The legal situation of Russian Jews , The Jews in Russia: Based on testimonies from Christian Russians ). In 1895, Franzos initiated (and financed) the founding of Concordia Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft . Franzos suffered from heart problems since 1901 and died in Berlin at the age of 55. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Berlin-Weißensee in an honorary grave in field A 1. His gravestone contains the inscription:

dream

“[Franzos] was determined to the last not to give up his dream of love and humanity, his Judaism, as well as the German Enlightenment . The Enlightenment was called to him to liberate and civilize Eastern Jewry, which was trapped in the fetters of orthodoxy, superstition and religious despotism. The absorption of Judaism in German culture, which he so revered, remained the main concern in all of his works, including the last novel Der Pojaz , which was only published after his death . "

Quotes

- "Every country has the Jews it deserves."

- "I had to do my duty in the small Jewish community as well as in the large German one."

- "Necessity is the only deity one can believe in without ever having to doubt or despair."

- "Let us finally understand the truth that only love can save us, but faith blindly."

- "I draw conclusions from facts that are firmly established as truth to me, I do not falsify facts in order to be able to draw conclusions from them."

Works

“Franzos always wrote - like a real columnist - on the border between journalism and fiction. He himself considered his beautiful feature articles about half-Asia to be pure literature. "

stories

- David the Bocher . Narrative. 1870.

- One only child. Narrative. 1873.

- The Jews of Barnow . Novellas ( The Shylock von Barnow - According to the higher law - Two saviors - The wild Starost and the beautiful Jütta - The child of atonement - Esterka Regina - Baron Schmule - The image of Christ - without inscription ). 1877.

- Young love. Novellas. 4th edition. 1879.

- Silent stories. 2nd Edition. Bonz Verlag, Stuttgart 1905.

- Moschko of Parma . Three stories ( Moschko von Parma , Judith Trachtenberg , Leib Christmas cake and his child ). 2nd Edition. Ruetten & Loening Verlag, Berlin 1984.

- My French novellas in verse. Breitkopf & Härtel publishing house, Leipzig 1883.

- The President . Narrative. Trewendt, Breslau 1884. Digitized from the Internet Archive

- The journey to destiny. Narrative. 3. Edition. Cotta, Berlin 1909.

- Tragic novels. 2nd Edition. Cotta, Berlin 1895.

- The shadow. Narrative. 2nd Edition. Cotta, Berlin 1895.

- The old doctor's god. Narrative. 2nd Edition. Cotta, Stuttgart 1905.

- A victim. Narrative. Engelhorn Verlag, Stuttgart 1893 ( Engelhorn's novel library. 10.8).

- The seeker of truth. Novel. 3. Edition. Cotta, Berlin 1896 (2 volumes).

- Inept people. Stories. 3. Edition. Cotta, Stuttgart 1894.

- Little Martin. Narrative. 3. Edition. Cotta, Stuttgart 1910.

- Body Christmas cake and his child. Narrative. Greifenverlag, Rudolstadt 1984. Digitized from the Internet Archive.

- All kinds of ghosts. Stories. 2nd Edition. Concordia publishing house, Berlin 1897.

- Man and woman. Novellas. 2nd Edition. Cotta, Stuttgart 1905.

- New novellas. 2nd Edition. Cotta, Stuttgart 1905.

- Old Damian and other stories. Cotta, Stuttgart 1905 (Cottasche reference library; 100).

- The Job of Unterach and other stories. Cotta, Stuttgart 1913 (Cottasche reference library; 181).

Travel reports

- Half Asia. Country and people of Eastern Europe. Cotta, Stuttgart 1897 ff.

- From half-Asia. Cultural images from Galicia, South Russia, Bukovina and Romania. Volume 1, 5th edition. 1914.

- From half-Asia. Cultural images from Galicia, South Russia, Bukovina and Romania. Volume 2, 5th edition. 1914.

- From the Don to the Danube. New cultural images from half of Asia. Volume 1, 3rd edition. 1912.

- From the Don to the Danube. Volume 2, 3rd edition. 1912.

- From the great plain. New cultural images from half of Asia. Volume 1, 2nd edition. 1897.

- From the great plain. Volume 2, 2nd edition. 1897.

- German rides. Travel and culture images .

- From Anhalt and Thuringia. Aufbau-Taschenbuchverlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7466-6071-8 . Editionhochufer.com, Hannover 2011, ISBN 978-3-941513-20-4 .

- From the Vosges. A trip to Alsace in 1903. Editionhochufer.com, Hanover 2010, ISBN 978-3-941513-12-9 .

- Erfurt. A travel report from 1901 (special print from Aus Anhalt and Thuringia ). Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-86680-321-3 (with a foreword by Steffen Raßloff ).

- In the Schwarzatal. A travel report from 1901 (special print from Aus Anhalt and Thuringia ). Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-86680-329-9 (with a foreword by Rolf-Peter Hermann Ose).

- From Vienna to Chernivtsi. "From half-Asia". With a contribution by Oskar Ansull. Editionhochufer.com, Hannover 2014, ISBN 978-3-941513-35-8 .

Novels

- A fight for justice . Novel. 2 volumes. Schottlaender, Breslau 1882.

- Judith Trachtenberg. Narrative. Concordia, Breslau / Berlin 1891.

-

The Pojaz . A story from the east. Cotta, Stuttgart / Berlin 1905. Digitized from the Internet Archive.

- New edition: The Pojaz. A story from the east. Edited and with an afterword by Petra Morsbach . Sankt Michaelsbund, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-939905-59-2 .

editor

- The story of the first work. Autobiographical essays. Titze, Leipzig 1894.

Work edition

- Selected Works. The Pojaz. 7th edition. Rotbuch-Verlag, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-434-54526-3 .

- Anna-Dorothea Ludewig (Hrsg.): A selection from his works. Olms, Hildesheim 2008, ISBN 978-3-487-13703-2 .

- Oskar Ansull (ed.): Name studies / Études de noms (1888/1897) bilingual Edition (German-French) Translation by Ariane Lüthi. hochufer.com, Hanover 2012, ISBN 978-3-941513-23-5 (comparative text edition). - Franzos' studies of the compulsory assignment of surnames to the Jewish population in Galicia at the end of the 18th century.

memory

- In his memory a memorial was erected in Chortkiv on April 30, 2017

literature

Books

- Oskar Ansull : Two spirit Karl Emil Franzos. A reading book by Oskar Ansull. Potsdam Library, German Cultural Forum Eastern Europe 2005, ISBN 3-936168-21-0 (with enclosed CD of the radio broadcast (NDR) by Oskar Ansull “A colorful spot on the caftan”).

- Petra Ernst (Ed.): Karl Emil Franzos. Writer between cultures (= writings of the Center for Jewish Studies. Volume 12). Studien-Verlag, Innsbruck 2007, ISBN 978-3-7065-4397-2 .

- Gabriele von Glasenapp : From the Judengasse. On the emergence and development of German-language ghetto literature in the 19th century. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-484-65111-3 (also dissertation, TH Aachen 1994).

- Günther A. Höfler: Psychoanalysis and development novel. Depicted on Karl Emil Franzos "Der Pojaz" (= publications of the Südostdeutschen Kulturwerk. Series B. Volume 47). Verlag des Südostdeutschen Kulturwerk, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-88356-049-9 .

- Sybille Hubach: Galician Dreams. The Jewish stories of Karl Emil Franzos (= Stuttgart works on German studies. Volume 157). Akademischer Verlag Heinz, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-88099-161-8 .

- Geneviève Humbert: Karl Emil Franzos (1848–1904). Peintre des confins orientaux de l'empire des Habsbourg (= Maison des Sciences de l'Homme de Strasbourg. Volume 13). Presses Universitaires, Strasbourg 1993, ISBN 2-86820-111-3 .

- Dieter Kessler: Maybe I am not a sufficiently modern person. Notes on Karl Emil Franzos (1848–1904) (= publications of the Südostdeutschen Kulturwerk. Series D. Volume 14). Verlag des Südostdeutschen Kulturwerk, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-88356-033-2 .

- Anna-Dorothea Ludewig (Ed.): Traces of a European. Karl Emil Franzos as a mediator between cultures. Olms, Hildesheim 2008, ISBN 978-3-487-13468-0 .

- Anna-Dorothea Ludewig: Between Chernivtsi and Berlin. German-Jewish identity constructions in the life and work of Karl Emil Franzos (1847–1904) (= Haskala. Volume 37). Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-487-13702-5 (also dissertation at the University of Potsdam; according to the Moses Mendelsohn Center, the first scientific biography of the French.) GoogleBooks

- Jolanta Pacyniak: The work of Karl Emil Franzos in the field of tension between the cultures of Galicia. A reflection of the contemporary discourse . Diss. Uni Lublin 2009, ISBN 978-83-227-3045-4 .

- Fred Sommer: "Half-Asia". German nationalism and the Eastern European works of Emil Franzos (= Stuttgart works on German studies. Volume 145). Akademischer Verlag Heinz, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-88099-149-9 .

- Carl Steiner: Karl Emil Franzos. 1848-1904. Emancipator and assimilationist (= North American studies in nineteenth-century German literature. Volume 5). Lang Verlag, New York 1990, ISBN 0-8204-1256-2 .

- Andrea Wodenegg: The image of the Jews of Eastern Europe. A contribution to the comparative imagology using text examples by Karl Emil Franzos and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (= European university publications. Series 1. Volume 927). Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-8204-8808-1 .

- Herwig Würtz (Ed.): Karl Emil Franzos (1848–1901). The poet of Galicia; for the 150th birthday. City Library, Vienna 1998 (catalog of the exhibition of the same name October 1998 to January 1999 in the Vienna City Hall).

Essays

- Jan-Frederik Bandel: The disappointed assimilator. The first German-Jewish bestseller: A hundred years ago, Karl Emil Franzos' ghetto novel “Der Pojaz” was published. In: Jüdische Allgemeine Zeitung. June 30, 2005.

- Heinrich Benedikt : Crown Prince Rudolf and Karl Emil Franzos. In: Austria in history and literature. 16, 1972, pp. 306-319.

- Roland Berbig: From half-Asia to European human life. Karl Emil Franzos and Paul Heyse. In: Hugo Aust, Hubertus Fischer (ed.): Boccaccio and the consequences. Fontane, Storm, Keller, Ebner-Eschenbach and the novella art of the 19th century (= Fontaneana. Volume 4). Spring conference of the Theodor Fontane Gesellschaft e. V. May 2004 in Neuruppin. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3458-9 , pp. 135-153.

- Andrei Corbea Hoișie : Not a “Bukovinian poet”. Karl Emil French. In: Zwischenwelt. Journal of the Culture of Exile and Resistance. Vol. 17, No. 2, 2000, pp. 23-25. ISSN 1563-3438

- Berlin booklets on the history of literary life. Volume 6 (2004), ISSN 0949-5371 ( online , with a focus on Karl Emil Franzos)

- Ludwig Geiger : KE French. In: Yearbook for Jewish History and Literature. 11, 1908, pp. 176-229. ( compactmemory.de ( Memento from February 11, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )), also in: Die Deutsche Literatur und die Juden. (Chapter 12: lexikus.de )

- Ernst Joseph Görlich: Franzos, Karl Emil. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961, ISBN 3-428-00186-9 , p. 378 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Alfred Klaar : Karl Emil Franzos. In: Biographisches Jahrbuch. Volume 10, 1907.

- Margarita Pazi : Karl Emil Franzos' concept of assimilation and experience of assimilation. In: Hans Otto Horch (Ed.): Conditio Judaica. Judaism, anti-Semitism and German-language literature from the 18th century to the First World War; interdisciplinary symposium of the Werner Reimers Foundation. Volume 2, Niemeyer, Tübingen 1989, ISBN 3-484-10622-0 , pp. 218-233.

Web links

- Literature by and about Karl Emil Franzos in the catalog of the German National Library

- French manuscripts in German-language archives and libraries

- Works by Karl Emil Franzos in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Karl Emil Franzos and Erfurt

- Annotated link collection of the university library of the FU Berlin ( Memento from October 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (Ulrich Goerdten)

- Markus Winkler: Chernivtsi Judaism: a myth on the edge of Europe?

- The monument in Chortkiv

Individual evidence

- ^ Karl Emil Franzos: The Pojaz. 6th edition. eva Taschenbuch, 2002, ISBN 3-434-46215-5 , p. 5.

- ↑ a b c d e Harald Seewann , Raimund Lang : Karl Emil Franzos - Student History Notes. In: Chernivtsi Small Fonts. Series of publications by the traditional association of Catholic Czernowitzer Pennäler. Issue 28, 2014.

- ^ Helge Dvorak: Biographical Lexicon of the German Burschenschaft. Volume II: Artists. Winter, Heidelberg 2018, ISBN 978-3-8253-6813-5 , pp. 214-218.

- ↑ Otto Mühlwerth: One Hundred Years of fraternity Teutonia Vienna. Horn 1968.

- ^ Andrei Corbea-Hoișie: Half-Asia. In: Johannes Feichtinger , Heidemarie Uhl (Hrsg.): Rethinking Habsburg. Diversity and ambivalence in Central Europe. 30 key words in cultural studies. Böhlau, Vienna 2016.

- ↑ Salomon Wininger: Great Jewish National Biography. Volume II, Orient Printing House, Czernowitz 1927, p. 307.

- ↑ Great Jewish National Biography, Volume 2 (1927), p. 307

- ^ Franzos, Mrs. Ottilie (zeno.org).

- ↑ a b c Ralf Bachmann: Why the "Pojaz" mustn't die. In: this side. Journal of the Humanist Association, 22nd year, 3rd quarter, No. 84/2008, p. 27.

- ↑ Ralf Bachmann: Why the "Pojaz" mustn't die. In: this side. Journal of the Humanist Association, 22nd year, 3rd quarter, No. 84/2008, p. 28.

- ^ New edition: Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-548-30283-1 (The woman in literature).

- ↑ У Чорткові відкрили пам'ятник австрійському письменнику. Ukrainian

Remarks

- ↑ Certificate entry: the candidate has been declared qualified.

- ↑ Franzos first coined the word in his feature article "Todte Seelen." (Neue Freie Presse. Vienna. March 31, 1875.) It became a winged word and was first included in Georg Büchmann's collection of " Geflügelte Words " in 1895 (18th edition. Haude and Spener, Berlin 1895, p. 221).

- ↑ translated into sixteen languages

- ↑ Contents: The brown pink. The witch , the cousins of Brandenegg .

- ↑ Contents: The worst and the best. A coward

- ↑ translated into fifteen languages

- ↑ A special edition was published in Halle / Saale in 2005 under the title “Aus Anhalt”

- ^ Published posthumously. The book was based on a concept that was more than 30 years old, which was then revised by KE Franzos, but was no longer published during his lifetime due to the unfavorable socio-political climate in Germany. A Russian translation authorized by him appeared in St. Petersburg as early as 1894.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | French, Karl Emil |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian writer and publicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 25, 1848 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | near Czortkow in Russian Podolia, today Ukraine |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 28, 1904 |

| Place of death | Berlin |