Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (* probably 1525 in Palestrina , Latium region , † February 2, 1594 in Rome) was an Italian composer who succeeded the Franco-Flemish style, singer and bandmaster of the Renaissance and an outstanding master of church music .

Live and act

In addition to the first name Giovanni and the actual family name Pierluigi , the denomination of origin da Palestrina was added during the composer's lifetime , so that today it is common in music history to speak briefly of Palestrina. He was the son of Sante and Palma Pierluigi from Palestrina (historically Praeneste ) in the vicinity of Rome, where the family had been based at least since the middle of the 15th century. The year of birth results from the obituary of the Lorraine clergyman and member of the papal curia , Melchior Major, from February 1594 on the composer's death with the indication Vixit annis LXVIII ("lived 68 years"), which results in a date of birth between the 3rd February 1525 and February 2, 1526. Giovanni's first mention was in the will of his grandmother Iacobella Pierluigi, who lived in Rome, on October 22, 1527, in which she transferred her estate to her sisters and children and also mentions her grandson, about two years old, "Giov", who received some household items. According to a census by Pope Clement VII in 1526/1527 , a Santo de Prenestina lived with his family near the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome. Giovanni had three siblings, Giovanni Belardino, Palma and Silla; the latter also became a musician with only a few traditional compositions. The mother Palma died in 1536.

In a contract between the cathedral chapter of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome and the singer and conductor Giacomo Coppola of October 25, 1537, six choirboys entrusted to the latter are also mentioned, among them a "Joannes de Palestrina". Because the Kapellmeister there often changed after a few years, in addition to Coppola, Rubinus Mallapert (around 1520–1573), as well as a certain Roberto and a Firmin le Bel, could be Palestrina's teachers; however, there is no reliable information about his further career. On October 28, 1544, the composer signed a contract with the canons of the Cathedral of San Agapito in his hometown Palestrina, in which he undertook to conduct the choral singing on a daily basis at the celebration of Mass , Vespers and Compline , to play the organ on festive days as well also to give musical lessons to canons and choirboys. During this time, Palestrina married on June 12, 1547, Lucrezia Gori from a respected family in his hometown; the sons Rodolfo (1549–1572), Angelo (1551–1575) and Iginio (1558–1610), who emerged from the marriage, were later all active as composers.

As Mallapert's successor, Palestrina was appointed magister cantorum on September 1, 1551 without the usual examination procedure at the Cappella Giulia of St. Peter's Church in Rome, possibly through the protection of the bishop of his hometown Giovanni Maria Ciocchi, who later became Pope Julius III. (Term of office 1550–1555). At least Palestrina later dedicated his first publication Missarum liber primus (Rome 1554) to this, a stately choir book that begins with the cantus firmus - mass Ecce sacerdos magnus as a tribute composition. At the beginning of 1555, Palestrina was appointed a member of the papal chapel ( Sistine Chapel ) by order of Julius III, also here without the specified examinations and without the usual resolution of the other singers. During this period of service, Palestrina's first book of madrigals for four votes was published. After the death of Julius III. on March 23, 1555, Marcellus II received his pontificate , which lasted only three weeks, but with its humanistic and musical reformist impulses had a clear influence on Palestrina (composition of the Missa Papae Marcelli , around 1562). The successor Paul IV (1555–1559) decreed in his backward-looking reform zeal that the members of the Sistine Chapel can only be clerics , so that on July 30, 1555, among others, the three married members, including Palestrina, with a lifelong Pension were dismissed.

Palestrina took over on 1 October 1555 as the successor of Orlando di Lasso , the Kapellmeister of the Cappella Pia at St. John Lateran , the Roman See of the Pope, who was finance and personnel considerably worse equipped than its previous positions. Nevertheless, the composer strengthened his reputation with the appearance of madrigals in quick succession in renowned collective prints. During this time he composed his eight-part improperia for two choirs, first performed on Good Friday 1560, which made such a deep impression that Pope Pius IV (1559–1565) requested a copy of it for the papal chapel. Palestrina left his office at the Lateran Basilica on August 3, 1560 and became head of the Cappella Liberiana on March 1, 1561 at Santa Maria Maggiore , the place of his education, where he stayed for about four years. During this time there were discussions in the last part of the Council of Trent (1545–1563) on liturgical reform and church music, and Palestrina's music aroused the special interest of Cardinal Rodolfo Pio da Carpi (1501–1564) and the circle of him around Council participants. A year later, Palestrina dedicated his annual liturgical cycle of motets , Motecta festorum totius anni , his first individual print to the cardinal . Cardinal Ippolito II. D'Este , builder of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli, hired the composer for three months for his lavishly occupied chapel in the summer of 1564; Palestrina's first book of motets (five to seven parts) was dedicated to him.

The Council of Trent decided on special aesthetic and stylistic requirements for church music; this also includes the unconditional intelligibility of the word in the word-tone relationship. The cardinals Carlo Borromeo and Vitellozzo Vitelli were commissioned to implement the resolutions, which also included a reform of the papal chapel . In this context, the Seminario Romano was founded on February 1, 1565 as a training center for the next generation of priests; Palestrina was appointed musical director and teacher at this institution shortly afterwards. On April 28, 1565, there was a hearing in Cardinal Vitelli's house, at which the papal choir had to perform some recent mass settings, also by Palestrina, so that the appropriateness of the polyphonic style for the music of worship could be assessed according to the new guidelines. It can be assumed that Palestrina's Missa Papae Marcelli was also performed on the occasion . After the honorary title modulator pontificus (for example: "papal composer") was awarded to Palestrina by Pius IV on June 6th of this year and his monthly pension was increased, the composer's increased importance for the church music reforms after the council results . Palestrina now had a reputation of European standing. His second and third mass books from 1567 and 1570 were dedicated to King Philip II of Spain, and Count Prospero d'Arco, Maximilian II's imperial envoy , negotiated with him about the successor to the vacant position of Kapellmeister at the Viennese court. In the end, however, the emperor was unable to meet Palestrina's high financial demands, which is why Philippe de Monte got the job.

After Giovanni Animuccia , conductor and successor of Palestrina in 1555 at the Cappella Giulia of St. Peter's Basilica, died at the end of March 1571, Palestrina took over this position for the second time after only a week had passed. In addition to the daily duties to be performed, other tasks arose for him in the 1570s. Pope Gregory XIII (1572–1585) commissioned the composer and singer Annibale Zoilo (1537–1592) in a decree of October 15, 1577 to reform the choral chants ( Graduale Romanum ); both started work immediately and completed it the next year. However, this version was never printed because the linguistic and musical interventions in the chorales went too far, especially for King Philip II of Spain, whereupon the Pope withdrew the commission in 1578. Palestrina was also active for the Arciconfraternita della Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini e Convalescenti , a Roman piety movement of that time, for which he made musical contributions in 1576 and 1578. A closer relationship developed between him and the court of the Gonzaga in Mantua . Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga strove for a counter-Reformation center in Italy and built the castle church, Basilica Palatina di Santa Barbara , in Mantua , for which he ordered ten choral masses at Palestrina based on a liturgical tradition specially cultivated in Mantua. He received the first four-part Alternatim Mass on February 2, 1568, the remaining nine five-part between November 1578 and April 1579. The attempt to win Palestrina for the position of Kapellmeister at the new basilica in 1583 failed because of his high salary.

In the first ten years of Palestrina's renewed ministry at St. Peter, there were several deaths in his family. His brother Silla died on New Year's Day 1573, his eldest sons Rodolfo and Angelo in 1572 and 1575, and on August 22, 1580 his wife Lucrezia fell victim to a virus epidemic in Rome. In the following year, 1581, three of his grandchildren died. This was possibly reflected in the composition of his second four-part book of motets, which contains a striking number of funeral music. Palestrina then apparently decided to become a priest and asked his employer, Pope Gregory XIII., In the autumn of 1580 to receive minor orders; this was approved and carried out on December 7th of that year in the church of San Silvestro al Quirinale . In January 1581 he received a benefice at the Church of Santa Maria in Ferentino, southeast of Rome. A little later he gave up the intention to go to the priesthood again and on March 28, 1581 married the wealthy widow of the papal fur supplier, Virginia Dormoli. As the owner of a fur business, he carefully invested the income in real estate.

In the new phase of his life, Palestrina developed an intensive and extensive composition and publication activity. A large number of madrigals and motets appeared in a large number of collective prints, and many significant individual prints came out, such as books of masses, motets, and madrigals, and the two collections of five-part sacred madrigals. The great cyclical works of his later period also include the Hohelied motets (1583/1584), the Lamentations (1588), the Magnificat collection (1591) and the two annual liturgical cycles with hymns (1589) and offerings (1593). In the spring of 1593 he intended to return to his homeland to take over the vacant position of cathedral music director and organist until the regular occupation. But before the contract was signed, Palestrina fell seriously ill in early 1594 and died on the morning of February 2nd. He was buried in a crypt of St. Peter, in which other family members were already resting. His grave bears the inscription Musicae princeps ("Prince of Music"). His successor in the office of director of the Cappella Giulia was Ruggiero Giovannelli on March 12 , and the position of composer at the papal chapel went to Felice Anerio on April 3, 1594 .

meaning

In the second half of the 16th century, after the knowledge about the psychological, ethical and political effects of music and thus its social significance ( Francesco Bocchi 1581), there were reform movements in religious life and thus also in liturgical music. This gave rise to the orders of the Jesuits and Filipinos on the one hand, and the reform efforts of the Council of Trent on the other, at which in its last session the usefulness of polyphonic music for the devotion of the listener due to the lack of intelligibility of the text was critically discussed. Even should parody masses with templates of "lascivious" madrigals and chansons are repressed; The most energetic advocate of such demands was Pope Sixtus V. In this context, Palestrina was first described in 1609 by the composer Agostino Agazzari (1578–1640) as the “savior of church music”, who with his Missa Papae Marcelli met such reform demands in an exemplary manner. Strangely enough, he also counted Palestrina's music among the forerunners of the figured bass style. It should be noted, however, that given the prevailing diversity of opinion among the Council participants, there was no serious fear of restricting or even banning polyphonic music. Palestrina has shown in his works that he has mastered both the previous polyphonic style and the recently desired reform style. He did not join the efforts of a church music reform style as represented by the composers Giovanni Matteo Asola and Vincenzo Ruffo . For Palestrina, intelligibility of the text was not a prerequisite for vocal church music, but only an option for compositional techniques.

From the early 17th century, the repertoire of the Sistine Chapel was more and more dominated by the compositions of Palestrina, which continued into the 19th century. A number of the composer's works were subsequently arranged by other masters, such as the Missa Papae Marcelli by Giovanni Francesco Anerio , who reduced this mass to four voices in 1619, or by Francesco Soriano , who expanded the same mass to double choirs in 1609. Many of Palestrina's motets were re-texted for extended use in the 18th century. Johann Sebastian Bach arranged the six-part Missa sine nomine for voices, cornetti , tromboni and figured bass. In the history of music theory, a contrapuntal teaching tradition emerged from the Palestrina generation of students, which led to the Gradus ad Parnassum by Johann Joseph Fux (Vienna 1725), in which the contrapuntal style of Palestrina is taught in dialogue form. This work became one of the most influential counterpoint textbooks well into the 19th century, offered Haydn , Mozart and Beethoven the opportunity to incorporate counterpoint into the composition and gave the church music restoration movements of the 19th century the foundation in the theory of composition.

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann , in his essay “Old and New Church Music” (1814), highlighted Palestrina's work as “true music from the other world”, and from around 1830 the musical reform movements were mostly based on Palestrina as the main representative of classical vocal polyphony. This culminated in the Cecilian movement , which originated in Munich and Regensburg , with the result that outstanding composers such as Franz Liszt , Charles Gounod , Joseph Rheinberger , Johannes Brahms and Anton Bruckner also dealt artistically with the music of Palestrina. Hans Pfitzner (1869–1949) wrote and composed in his “Musical Legend” Palestrina 1910 to 1915 the story of the composer as a late romantic confessional drama of ideas in which quotations from Palestrina's works are used as leitmotifs. Finally, the Danish musicologist has Knud Jeppesen Christian (1892-1974) analyzes the manner set in Palestrina's works and in his counterpoint represented the historically correct counterpoint of the composer of the 1935th

The Palestrina style can be described as a synthesis between the contrapuntal art of Franco-Flemish music and the Italian sense of sound. With regard to the actually present, mutable and highly differentiated, complex compositional style of the master, the concept of the Palestrina style is simplified more in the sense of a historically solidified and doctrinally communicable sentence model, which is fundamentally different from the later concertante style as stile antico of the figured bass age. The main characteristic is the melodic, rhythmic and harmonic, finely tuned balance of a work on all levels of the musical structure. This is the result of a development in the history of music in which the papal band and their previous singer-composers played a major role. The aim was to relate all the relevant sizes and typesetting parts of a work to one another in a structural balance. The melody prefers second steps and creates the impression of unity in its balance of upward and downward movements. Larger intervals in the melody are regularly answered with smaller steps in the opposite direction; ascending movements usually begin with a larger interval, followed by smaller ones; with descending movements it is the other way round. The formation of symmetries, sequences and phrase-like repetitions is avoided, as is the juxtaposition of strongly contrasting note lengths within melodies. Accents are only determined by the declamation of the text and dissonant sounds are always prepared and resolved as continuation , lead and alternating note dissonances. In terms of the density of movements, the relationship between the sound of a voice and a pause, Palestrina strives for a balance, which in terms of sound amounts to the ideal of four-part music. Thus, the four-part works have the densest structure of the movement, with the five-part works the pause portion is on average a fifth to a quarter, with the six-part works a quarter to a third. When a sentence is played, the alternation between full and low voicing results in a continuous fluctuation in the density of the sentence.

Works (summary)

-

Total expenditure

- Pierluigi Palestrina's works , 33 volumes, Leipzig without year [1862–1907]

- Le opere complete di Giovanni Perluigi da Palestrina , 35 volumes, Rome 1939–1999

- Trade fairs, individual prints

- "Missarum liber primus", Rome 1554

- "Missarum liber secundus", Rome 1567

- "Missarum liber tertius", Rome 1570

- "Missarum cum quatuor et quinque vocibus, liber quartus", Venice 1582

- "Missarum liber quintus quatuor, quinque, ac sex vocibus concinendarum", Rome 1590

- "Missarum cum quatuor vocibus, liber primus", Venice 1590

- "Missae quinque, quatuor ac quinque vocibus concinendae [...] liber sextus", Rome 1594

- "Missae quinque, quatuor ac quinque vocibus concinendae [...] liber septimus", Rome 1594

- "Missarum cum quatuor, quinque & sex vocibus, liber octavus", Venice 1599

- "Missarum cum quatuor, quinque & sex vocibus, liber nonus", Venice 1599

- "Missarum cum quatuor, quinque & sex vocibus, liber decimus", Venice 1600

- "Missarum cum quatuor, quinque & sex vocibus, liber undecimus", Venice 1600

- "Missarum cum quatuor, quinque & sex vocibus, liber duodecimus", Venice 1601

- "Missae quattuor octonis vocibus concinendae", Venice 1601

(a total of 113 masses in 14 books)

- Magnificat individual printing

- "Magnificat octo tonum. Liber primus […] nunc recens in lucem editus ”, Rome 1591

- Magnificat cycles

- 8 Magnificat toni I – VIII with four voices, setting odd stanzas and 8 Magnificat toni I – VIII with four parts, setting even stanzas, 1591

- 8 Magnificat toni I – VIII with four voices, setting of even stanzas

- 8 Magnificat toni I – VIII with five to six voices, setting of even stanzas

- Magnificat individual works

- Magnificat quarti toni to four voices, setting of even stanzas

- Magnificat sexti toni for four voices, setting of even stanzas

- Magnificat primi toni to eight voices, setting odd / even stanzas

(35 Magnificat settings in total)

- Litanies-individual print and single works

- Individual print “Litaniae Deiparae Virginis musica D. Ioannis Petri Aloysii Praenestini […] cum quatuor vocibus”, Venice 1600

- “Litaniae Beatae Mariae Virginis” with three to four voices, 1600

- “Litaniae Beatae Mariae Virginis” with three and four voices, 1596

- “Litaniae Beatae Mariae Virginis” with five voices, approx. 1750, opus dubium

- “Litaniae Beatae Mariae Virginis” with six voices, probably autograph

- "Litaniae Beatae Mariae Virginis" (I) to eight votes (anonymous)

- "Litaniae Beatae Mariae Virginis" (II) to eight votes (anonymous)

- “Litaniae Domini” (I) with eight votes

- “Litaniae Domini” (II) with eight votes

- "Litaniae Domini" (III) to eight votes (anonymous)

- “Litaniae sacrae eucharistiae” (I) with eight votes

- “Litaniae sacrae eucharistiae” (II) with eight votes

(a total of 11 litany settings)

- Lamentations

- Individual print: "Lamentationum Hieremiae prophetae, liber primus", Rome 1588

- Cycle 1 (liber primus): 14 lamentations

- Cycle 2 (liber secundus): 12 lamentations

- Cycle 3 (liber tertius): 12 lamentations

- Cycle 4 (liber quartus): 12 lamentations

- Cycle 5 (liber quintus): 12 lamentations

- Individual lessons: 10 lamentations

(a total of 72 lamentation settings)

- Hymns

- Individual print: "Hymni totius anni, secundum sanctae romanae ecclesiae consuetudinem, quattuor vocibus concinendi, necnon hymni religionum", Rome 1589

(77 hymns in total)

- Motets, offertories, improperies, Marian settings, cantica and psalm settings

- Individual print "Motecta festorum totius anni cum communi sanctorum [...] quaternis vocibus [...] liber primus", Venice 1564, numerous reprints

- Individual print "Liber primus [...] motettorum, quae partim quinis, partim senis, partim septenis vocibus concinatur", Rome 1569

- Individual print "Motettorum quae partim quinis, partim senis, partim octonis vocibus concinatur, liber secundus", Venice 1572 (with an additional 1 motet each by Palestrina's sons Angelo and Rodolfo and two motets by his brother Silla Pierluigi da Palestrina)

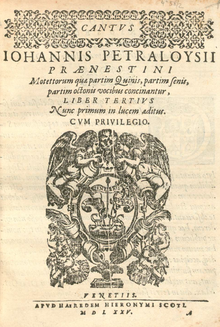

- Individual print “Motettorum quae partim quinis, partim senis, partim octonis vocibus concinatur, liber tertius”, Venice 1575

- Individual print “Motettorum quinque vocibus liber quartus”, Rome 1583/84, numerous reprints

- Individual print “Motettorum quatuor vocibus, partim plena voce, et partim paribus vocibus, liber secundus”, Venice 1584

- Individual print “Motettorum quinque vocibus liber quintus”, Rome 1584

- Individual print “Offertoria totius anni, secundum sanctae romanae ecclesiae consuetudinem, quinque vocibus concinenda […] pars prima”, Rome 1593

- Individual print "Offertoria totius anni, secundum sanctae romanae ecclesiae consuetudinem, quinque vocibus concinenda [...] pars secunda", Rome 1593

(a total of 336 authentic compositions and 81 works of uncertain attribution or doubtful authenticity)

- Spiritual madrigals

- Individual print “Il primo libro de madrigali a cinque voci”, Venice 1581

- Individual print “Delli madrigali spirituali a cinque voci […] libro secondo”, Rome 1594

(56 spiritual madrigals in total)

- Secular madrigals and canzonets

- Individual print “Il primo libro di madrigali a quatro voci”, Rome 1555, many reprints

- Individual print “Il secondo libro di madrigali a quatro voci”, Venice 1586

(93 secular madrigals in total)

- Instrumental music

- "Recercate", 8 ricercare over the 8 modes for four voices

- “Esercizi (IX) sopra la scala” for four voices, opus dubium

Literature (selection)

Monographs

- A. de Chambure: Palestrina. Catalog des oevres religieuses , Volume 1. Paris 1989.

- Karl Gustav Fellerer : The Palestrina style and its meaning in the vocal church music of the 18th century. Augsburg 1929, reprint Wiesbaden 1972.

- Karl Gustav Fellerer: Palestrina. Life and work. Regensburg 1930, 2nd edition Düsseldorf 1960.

- J. Garratt: Palestrina and the German Romantic Imagination: Interpreting Historicism in Nineteenth-Century Music. Cambridge 2002.

- Michael Heinemann : Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and his time. Laaber-Verlag, Regensburg 1994.

- Christoph Hohlfeld , Reinhard Bahr: School of musical thought. The cantus firmus movement in Palestrina. Florian Noetzel Verlage, Wilhelmshaven 1994, ISBN 3-7959-0649-0 .

- Johanna Japs: The Madrigals by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. Genesis - Analysis - Reception. Wißner-Verlag, Augsburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-89639-524-5 .

- Knud Jeppesen: counterpoint (vocal polyphonic). Copenhagen / Leipzig [1930], German as counterpoint. Classical vocal polyphony textbook. Leipzig 1935, 10th edition Wiesbaden 1985.

- M. Janitzek, W. Kirsch (Ed.): Palestrina and the classical vocal polyphony as a model for church music compositions in the 19th century. Kassel 1995 (= Palestrina and church music in the 19th century, volume 3.)

- W. Kirsch: The Palestrina image and the idea of “true church music” in literature from around 1750 to around 1900. A commented documentation. Kassel 1999 (= Palestrina and church music in the 19th century, No. 2.)

- KS Nielsen: The Spiritual Madrigals of GP da Palestrina. Dissertation. Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 1999.

- Reinhold Schlötterer: The composer Palestrina. Basics, appearances and meaning of his music. Wißner-Verlag, Augsburg 2002, ISBN 3-89639-343-X .

- Marco Della Sciucca: Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. L'Epos, Palermo 2009, ISBN 978-88-8302-387-3 .

Essays

- Peter Ackermann: "Motet and Madrigal. Palestrina's Song of Songs motets in the field of tension of counter-Reformation spirituality", In: P. Ackermann, U. Kienzle, A. Nowak (Ed.): Festschrift W. Kirsch. Tutzing 1996, pp. 49-64. (= Frankfurt Contributions to Musicology, No. 24.)

- E. Apfel: "On the history of the origins of the Palestrina sentence", in: Archive for Musicology No. 14, 1957, pp. 30–45.

- P. Besutti: " Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina e la liturgia mantovana" , In: Congress report Palestrina 1986 . Palestrina 1991, pp. 155-164.

- V. Donella: "Palestrina e la musica al Concilio di Trento" , In: Rivista internazionale di musica sacra, No. 15, 1994, pp. 281-298.

- Helmut Hucke: "Palestrina as an authority and role model in the 17th century", In: Congress report Venice / Mantua / Cremona 1968 , Venice 1969, pp. 253–261.

- P. Lüttig: "The Palestrina style as a sentence ideal in music theory between 1750 and 1900", in: Frankfurter Contributions to Musicology, No. 23, Tutzing 1994

- R. Meloncelli: "Palestrina e Mendelssohn ", In: Congress report Palestrina 1986 , Palestrina 1991, pp. 439-460.

- Wilhelm Osthoff: "Palestrina e la leggenda musicale di Pfitzner", In: Congress report Palestrina 1986 , Palestrina 1991, pp. 527-568.

- H. Rahe: "The structure of the motets of Palestrina", In: Kirchenmusikalisches Jahrbuch, No. 35, 1951, pp. 54–83.

- Reinhold Schlötterer: "Structure and composition methods in the music of Palestrina", In: Archive for Musicology, No. 17, 1960, pp. 40–50.

- RJ Snow: "An Unknown" Missa pro Defunctis "by Palestrina", In: E. Cesares (Ed.): Festschrift J. López-Calo. Santiago de Compostela 1990, pp. 387-430.

See also

Movie

The film Palestrina - Prince of Music was shot in 2009 about the composer's life and work . Production ZDF / Arte , director: Georg Brintrup .

Trivia

- Geography: The Palestrina Glacier on the West Antarctic Alexander I Island bears his name in honor of the composer

- Astronomy: The asteroid (4850) Palestrina , discovered in 1973, got its name in honor of the composer

Web links

- Works by and about Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina in the German Digital Library

- Sheet music and audio files by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina in the International Music Score Library Project

- Sheet music in the public domain by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina in the Choral Public Domain Library - ChoralWiki (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Part Volume 13. Bärenreiter and Metzler, Kassel and Basel 2005, ISBN 3-7618-1133-0 .

- ↑ Marc Honegger, Günther Massenkeil (ed.): The great lexicon of music. Volume 6: Nabakov - Rampal. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau a. a. 1981, ISBN 3-451-18056-1 .

- ^ Internet Movie Database

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Palestrina, Giovanni Pierluigi da |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sante da Palestrina, Giovanni Pietro Aloisio; Sante, Giovanni Pierluigi; Sanctis, Johannes Petrus Aloisius (Latin) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian composer and conductor of the Renaissance |

| DATE OF BIRTH | uncertain: 1525 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Palestrina |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 2, 1594 |

| Place of death | Rome |