Roussolakkos

| Roussolakkos | |

|

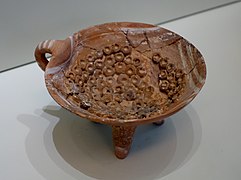

North-western part of the archaeological site |

|

| meaning | Minoan city |

| Start of building: | unknown |

| founding | unknown |

| Heyday | 2000–1450 BC Chr. |

| Given up | around 1250 BC Chr. |

| discovery | 1902 |

| Height: | 10 m |

| Location: | 35 ° 11 '43.1 " N , 26 ° 16' 32.1" E |

| Directions | Sitia - Palekastro |

| opening hours | Tue – Sun 8 am–3pm |

| entry | 2, - € |

Roussolakkos ( Greek Ρουσσολάκκος , also Ρουσολάκο Rousolako 'red pit') is the name of the archaeological site of a Minoan town in the municipality of Sitia in the east of the Greek island of Crete . It is located at a height of about 10 meters about 250 meters southwest of Chiona beach (Παραλία Χιόνα) on the east coast of Crete on the Levantine Sea . Because of its proximity to Palekastro , 1.5 kilometers to the west, the archaeological site is also known in publications as Palaikastro .

location

Roussolakkos, the "red pit", is named after the reddish colored fine and impermeable marl sandstone of the small depression around the excavation site. The Minoan city covered an area of about 600 × 600 meters, of which an area of about 10,000 m² has been excavated, but has been partially backfilled. In the past it was located directly on the beach, but is now over 200 meters from the coast due to alluvial deposits.

In the vicinity of the archaeological site there is pastureland, but also olive plantations and vineyards. North of Roussolakkos is the 89.79 meter high hill Kastri (Καστρί) 700 meters away , 1.5 kilometers south of the summit of the 254.75 meter high Petsofas (Πετσοφάς). The north-south orientation of the coastal plain around Palekastro, interrupted by the Kastri directly on the coast, is about 5 kilometers, to the west towards Sitia, 15 kilometers away, it increases only slightly along the road. Cape Sideros (Ακρωτήριο Σίδερος or Κάβο Σίδερο), the north-eastern tip of Crete, is 14 kilometers north of Roussolakkos. The archaeological site of the Minoan Palace of Zakros is 11 kilometers south, that of the Palace of Petras 14.5 kilometers to the west.

history

Minoan time

The area on the coast near Palekastro was already settled at the end of the Neolithic , the so-called Copper Age. The first finds of a smaller scattered settlement date from the early Minoan period FM I B / II A after 2900 BC. BC, from which a building on Kastri hill and two buildings in Roussolakkos were located. Already during the first excavations at the beginning of the 20th century, early Minoan graves and ostotheques ( Larnakes ) were discovered in the vicinity . A large building from phase FM II B under block Χ of the excavation site resembles buildings from the same period in Vassiliki , Myrtos , Knossos , Tylissos and Phaistos . No buildings can be assigned with certainty to the phases of Early Minoan FM III and Middle Minoan MM I A, although corresponding ceramic finds are known.

In the time MM IB / MM II A from around 2000 BC. The pre-palace settlement developed into a planned city. At the same time the summit sanctuary Petsophas was founded south of Roussolakkos. Around 1900 BC BC, in the time of the Old Palace , there were contacts across the sea to Asia Minor and Egypt . After an earthquake around 1760 BC At the end of MM III A, the city was rebuilt in MM III B at the beginning of the new palace period . It now received a paved road system with drainage canals. From the end of this period there are again indications of earthquake damage, which the city around 1570 BC. Chr. Concerned.

Most of the building remains in Roussolakkos date from the period from the Middle Minoan phase MM III B to the late Minoan phase SM I B. They consist of local sideropetra (crystalline limestone) and conglomerate, as well as sandstone for door posts and ashlar masonry . Purple and blue-green slates were used to pave the streets and floors in the houses . Building 1 in the very north of the excavation site was the first in SM I A whose four outer walls were built as brickwork. Towards the end of SM I A around 1500 BC A seven centimeter thick layer of volcanic ash from the Thera eruption covered the region and one or more tsunamis at least nine meters high flooded the Palekastro plain. The buildings of Roussolakkos were doing almost to the foundations destroyed.

During the reconstruction in SM I B from around 1490 to 1460/40 BC As planned, wide streets, large city blocks and buildings with cuboid facades structured by protrusions and recesses, such as buildings 1, 2, 4 and 5 in the north sector, were built. The partly two-story houses had peristyle courtyards , large main rooms, cult basins, fountains and cisterns , house shrines with consecrated double horns made of alabaster and many magazines. Finds of richly decorated pottery, stone vases and panels with linear letters A indicate that they were used by wealthy traders. Other areas of the city, such as Buildings 2 and 6, remained in ruins. In the period from 1460 to 1440 BC There was a series of devastations from fires, probably due to enemy raids on the city. From the last of these horizons of destruction in SM I B come rich and well-crafted finds, among them the kouros of Palaikastro , a masterpiece of Minoan craftsmanship that was broken into several individual parts and discovered in and next to building 5 of the excavation site.

In contrast to other settlements in Eastern Crete in phases SM II and SM III A1 around 1440 to 1400 BC. A city that was largely rebuilt in the 3rd century BC, often on the old plan, suffered in the early period of SM III A2 between 1400 and 1320 BC Again destruction by fire, possibly at the same time as the final destruction of Knossos. The subsequent extensive reconstruction in SM III A2 and SM III B was followed by destruction by an earthquake in the middle of SM III B around 1250 BC. And leaving the city by the residents. After their abandonment, the settlement of the area was limited in phase SM III C from 1200 to 1100 BC. A small refuge on the 180 meter long and 15 to 30 meter wide plateau of the Kastri north of the excavation site, accessible only from the south . It is unclear whether it was a successor settlement to the inhabitants of Roussolakkos, newly arrived settlers or a castle of pirates who carried out their raids from here.

Greco-Roman time

From the Geometric to the Roman period, from the 8th century BC. BC to the 4th century AD, there was a sanctuary above block Χ of the archaeological site, of which four fragments of a limestone stele with an inscription were found in a pit near the block at the end of May 1904. It is known as the Hymn to the Dictean Zeus or Hymn of the Kouretes . The inscription on the stele written on both sides dates from the beginning of the 3rd century AD, but judging by the smooth meter , the text is from the Hellenistic period of the late 4th or early 3rd century BC. BC, based on older ideas and rites. In the hymn, the young Zeus is called as the “greatest kouros ” who “leaps on” herds, fields, ships, cities and young citizens, to return to Dikta as the almighty ruler at the head of the demons and to enjoy the hymn. Presumably the sanctuary, which could be assigned to the god by the inscription, was the center of Heleia (Ἥλεια), also Eleia (Ἑλεία), a city or an area of the Eteocretes , which according to inscriptions and the tradition by Strabo (10.4.6) had retained the cult of the dictean Zeus.

In around 900 BC The sanctuary for the young god of fertility was founded in the 3rd century BC and was initially uncovered. A festival of the rebirth of nature was celebrated annually, at which the initiation of young citizens took place before the summoned Zeus . Finds of bronze relief shields, life , weapons and many vessels are evidence of rich offerings. In later times (550 to 150 BC) a temple was built on the site of the sanctuary. The goblets, lamps and torches found show that wine was consumed in the cult of the night ceremonies. The temple developed from a local place of worship to a supra-regional religious center of Eastern Crete, the administration of which the Poleis Itanos , Praisos and Hierapytna claimed for themselves.

Initially, the Itanians were able to protect themselves from the Egyptian king Ptolemy VI. Claim Philometor against the Praisier. After the king's death in 145 BC BC, the withdrawal of the Egyptian troops from Itanos and the destruction of Praisos by the Hierapytnians, war broke out between Itanos and Hierapytna over the island of Leuke and Heleia, which borders on the Temple of Zeus. The Itanians, apparently militarily inferior, demanded intervention by the Roman Senate . This saw after the end of the war in 141 BC. BC, mediated by a Roman embassy under the former consul Servius Sulpicius Galba , in 140 BC. BC that a foreign court of arbitration should deal with the claims of the Hierapytnier.

The consul C. Laelius Sapiens commissioned Magnesia am Mäander with the arbitration award, the 132 BC. In favor of Itanos and of which ancient parts of the inscription can be seen built into the facade of the Toplou monastery . Hierapytna seems to have ruled the disputed area in the following period. Tied into various Cretan camps, Itanos in alliance with Lato and Knossos, Hierapytna with Olous and Gortyn , it came about 121 BC. To further battles for the border areas. Hierapytna meanwhile established a village in the disputed area, which was never the extraterritorial part of the temple itself, but the neighboring land.

After another war in 115 to 114 BC BC, which Itanos began in a presumably weak phase of Hierapytna, and repeated attempts at mediation by the Romans determined consul L. Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus 112 BC. B.C. again the magnets to pass a judgment on the border question, which confirmed the earlier decision in favor of Itanos. Subsequently, commissions from Milesian and possibly Roman Horothetai established the demarcation between the two poles, which was followed by the conclusion of an alliance and isopoly agreement between Itanos and Hierapytna. According to Diodorus , the settlement at the temple of Dictean Zeus was in the 1st century BC. No longer inhabited. Even after the complete Roman conquest of Crete in 67 BC. No major settlement emerged in the area, although the sanctuary was still in use. Apparently the temple was looted and destroyed by fanatical Christians in the late 4th century AD . Of the Zeus sanctuary, besides the hymn inscription, only the Tonsima of the temple with the relief representation of warriors on chariots and on foot and a relief fragment made of clay, probably from the gable of the building, which served the peasants of Palekastro as a quarry until modern times.

- Roussolakkos archaeological site

Research history

Already Thomas AB Spratt mentioned in his 1865 book Travels and Researches in Crete in the first volume “ Phoenician ” terracottas, which he saw at Palekastro in the early 1850s. These could be the two ornate terracotta panels that a trader discovered in a stall in the early 1880s and duly reported. They were acquired by the Sylloge in Candia, which later became the archaeological museum in Heraklion , and some of them were published as a sketch by Federico Halbherr in 1892 after his visit to Palekastro. Halbherr wasn't sure whether the plates came from sarcophagi or belonged to a building frieze. In October 1899 two molds for Minoan cult figures and symbols were found 150 meters northwest of the town of Palekastro , of which Stefanos Xanthoudidis made plaster casts and published the photos in March 1900 in connection with a description and evaluation.

Excavations from 1902 to 1906

From April to May 1902 the British School at Athens carried out the first preparatory excavations at Palekastro. They were under the direction of the archaeologist Robert C. Bosanquet , assisted by the architect of the Institute C. Heaton Comyn . Wilhelm Dörpfeld and David G. Hogarth had previously waived an excavation permit for the Palekastro plain in favor of the British School . First of all, Bosanquet dug an exploratory trench in the Roussolakkos field, which was designated by the locals. Here the edge of a slab was found that matched the terracotta slabs found in the 1880s and testified that the latter came from this part of the site. Bosanquet interpreted the uncovered building remains as that of a Mycenaean city, possibly the capital of Eastern Crete at the corresponding time. At the same time, he noticed the large number of earlier ceramics in the Kamares style , which were also in graves and on the Kastri . Boards with linear writing were also discovered during the first excavation campaign. A burial site called “beehive grave” by Bosanquet 275 meters east of Angathia (Αγκάθια) with an 8 meter long dromos , a relatively small burial chamber 2.30 meters in diameter and nine finds was later considered one of the earliest Minoan chamber tombs with a long (“Mycenaean “) Dromos identified in Eastern Crete from SM III A2 / B.

In the excavations from 1903 to 1905 Robert C. Bosanquet was assisted by Richard M. Dawkins , Charles T. Currelly and Marcus N. Tod . At the same time, John L. Myres examined the summit sanctuary of Petsophas, 900 meters southeast, and Wynfrid LH Duckworth and Charles H. Hawes studied the Minoan cemeteries in the area. The headquarters of the expedition was in Angathia between Roussolakkos and Palekastro. The excavation site in Roussolakkos was divided into regular blocks of several houses that were given Greek letters to distinguish them from the grid squares of the excavation site. Bosanquet included the coast at the bay of Kouremenos (Κουρεμένος) north of Kastri in the investigations.

From March 23, 1903, in addition to other Kamares ceramics, an early form of a wine press, jugs with a pointed spout and two pithoi , which in their arrangement probably played a role in the production of oil, peas, barley and some olive pits in jugs, were engraved in Roussolakkos Gemstones ( gems ), two of which were provided with three-sided seals, a pair of finely granulated amber earrings , the edge of a steatite bowl with four incised Minoan characters, a well-preserved woman's head carved from a bone and a series of four depictions of cult horns Stone found. In addition to the ceremonial axes from Kouremenos, two different sizes came from Roussolakkos, one only five centimeters from point to point. Geometric ceramics, bronzes comparable to those from the altar mound in Praisos and a scarab seal over the southeastern end of the former Minoan main street gave first indications of an ancient temple, which was suspected at this location based on the architectural terracottas that have already been found. A stratum of wood ash indicated a building made mainly of wood.

Richard M. Dawkins first tried in 1904 to synchronize various excavations from the beginning of the 20th century . To do this, he compared the findings from Roussolakkos with the results of the excavations carried out by Arthur Evans since March 1900 and with finds from Zakros , Vassiliki , Gournia and Phaistos on Crete and Phylakopi on Milos , Vaphio in Laconia and Mycenae in the Argolis . At the same time he tried the chronological development of Minoan art from the early Minoan to the beginning of the late Minoan period by comparing the strata of Roussolakkos with the grave goods found, for example at Ta Ellenika (Τὰ Ἑλληνικά) at the foot of the Kastri , but also ceramics from other sites, like Kato Zakros or Phylakopi, understandable. In addition to the rich finds of the year from the Minoan period, fragments of the hymn of the Kouretes and several fragments of the terracotta cornice of the ancient Zeus temple, which were mixed with so-called Mycenaean and archaic remains, were discovered in May 1904 . Finding the parts of the inscription led to the localization of the sanctuary of the dictaean Zeus in Roussolakkos, known from the arbitration rulings of the magnets.

|

|

|

|

|

||

The 1905 excavation campaign led by Dawkins ran from March 29 to June 17 with an average of 60 to 70 workers. From May the architect Vaclav Seyk (also Sejk) created a complete plan of the archaeological site. At the end of the season, Guy Dickins from New College in Oxford took on the task of packing and unpacking the finds for transport to the Candia Museum, among other work. The focus of the campaign was the temple area, which was completely exposed in the third and fourth seasons. No walls were found of the structure of the Temple of Zeus on an artificially leveled platform halfway up the south-eastern slope, near the end of the Minoan main street, only fragments of the terracotta decoration and the 36-meter-long remains of the peribolus surrounding the Temenos . The Temenos extended over most of the Minoan blocks Π and Χ as well as the road separating them. Only the location of the altar could be identified from the temple based on a 3 meter long and 0.25 meter thick layer of gray wood ash and the votive offerings, vases and lamps, bronze shields and a bronze lion, mostly from the archaic period from the 7th to the 5th century BC. BC, to be localized. The anathemas of large and small bronze shields are similar to those discovered in the Idean Grotto .

Although the excavations were intended to be completed in 1905, Richard M. Dawkins carried out an eight-day excavation in the vicinity of Roussolakkos in 1906, with the assistance of John P. Droop of Trinity College in Cambridge and about 10 workers. A field at the hamlet of Agia Triada on the road from Palekastro to Sitia was examined, where a few years earlier two stone forms for the production of two votive double axes, a female figure and other objects were found, the Plaka hill (Πλάκα), between the Petsofas and the cape Plaka, and the slopes and the plateau of the Kastri . Of the excavations, only the one on Plaka was reasonably successful, where a burial place was found in a cave.

Excavations in 1962 and 1963

The excavations of the British School at Athens in 1962 and 1963 under the direction of L. Hugh Sackett and Mervyn R. Popham focused on house Ν in Roussolakkos and the Minoan settlement of Kastri . Work began in 1962, in agreement with the Greek Archaeological Council, with the cleaning and exploration of the areas left open from previous excavations. This affected parts of blocks Β, Γ and Δ as well as the adjacent sections of the main road (from Β 12 to Δ 20).

The probes in blocks Β, Γ and Δ did not provide any significantly new insights. In block Β only three successive phases from SM I were recognized, an unexcavated section in block Γ contained some simple vessels and a test excavation in Δ 33 produced MM I ceramics from deeper layers as well as fragments from FM II and III above the rock floor. Investigations of a hill 400 meters northwest of Roussolakkos in the direction of Angathia yielded better results, where architectural remains from MM III, SM I and SM III were discovered. a. a wall made of MM III made of regular ashlar stones. It was later included in two rooms from SM I and SM III A, which separately contained a SM I B destruction layer and a characteristic SM I A stratum. The hill must therefore have been inhabited at least in places from MM III to SM III A.

The examined house Ν is characterized by its ceramic finds. It contained an undisturbed SM IB destruction layer, as it was only partially repopulated in rooms 12 and 19. Two of the six painted vases found are considered to be knossic imports, including a flip-top jug with an octopus decor . The four other vessels are in the retarding SM I A style that is characteristic of Eastern Crete. The decorated vases from the period of resettlement at the latest in SM III A1 are obviously based on Knossic models, only the undecorated utility ceramics show closer ties to Eastern Crete. The repopulation extends into phase SM III A2, whereas SM III B is absent. The style SM III C is limited to the Kastri settlement, whereas Roussolakkos probably remained uninhabited.

The excavations of 1962 and 1963 confirmed the assumption that the main phase of the building activity of the Minoan city was in MM III, a layer of destruction marked its decline in SM IB and a partial repopulation in SM III A apparently did not end violently, but with an exodus from which all valuable items were taken. The results of the excavations and the catalog of the finds were mainly compiled by L. Hugh Sackett. The study and catalog of ceramics and the drawing of the shards and some pots was done by Mervyn R. Popham. Peter M. Warren was responsible for the section on stone objects.

Excavations in 1972 and 1978

Areas of the Palekastro site were excavated in 1972 and 1978 by the Greek Archaeological Service under the direction of Costis Davaras . When examining two Minoan buildings with SM I ceramics in Vlychades (Βλυχάδες) near Roussolakkos, on the coast below Petsophas, one found among other things a channel with a double ax sign. About 300 meters southeast of Roussolakkos and 400 meters from the sea, a round structure with burned edges was discovered. The excavations in August 1978 revealed that it was a Minoan kiln , the easternmost of Crete. It was cut about 1.30 meters deep into the white chalk marl with a diameter of 2.68 meters and had a step 0.40 meters wide, interrupted by an opening in the east. It served as a tapping channel with a curvature of 0.65 meters high and the same width on the outside.

Excavations since 1986

The third series of excavations by the British School at Athens under L. Hugh Sackett and J. Alexander (Sandy) MacGillivray began in 1983 with a preparatory topographical and magnetic survey , based on which they estimated the size of the Minoan city to be 30 hectares . In the same year the architect Jan M. Driessen examined the quarries of Ta Skaria (Τα Σκαριά) on the seashore southeast of Roussolakkos, from which, according to Bosanquet (1901/02), the "yellow stone " from aeolianite in the area of the excavation site came. From 1986, the northern sector of Roussolakkos in particular, with buildings 1 to 7, was excavated, with building 6 belonging to block Μ, which had already been largely explored.

The most important find of the excavations was a chryselephantine statuette from the late Minoan phase SM I B, which is known under the name Kouros of Palaikastro . It was discovered broken into individual parts from 1987 to 1990 in and in front of House 5, first the torso with the arms, then the head and legs. MacGillivray saw the statuette, the embodiment of a youthful male figure, an equivalent to the Egyptian god Osiris , a ruler who dies and is reborn in the change of nature. He reminds of the dictaean Zeus of classical Greek antiquity, the young Zeus as the "greatest kouros", to whom the sanctuary was later consecrated in Roussolakkos and a temple was built.

Geophysical surveys to the southeast of the Roussolakkos archaeological site revealed in 2001 that the Minoan city extended over an even larger area than L. Hugh Sackett and J. Alexander MacGillivray assumed in 1983. Linear anomalies have also been discovered in the western sector, but these are difficult to interpret. In addition to another block of Minoan houses, an approximately 120 × 60 meter structure could also be the central courtyard of a palace, which has not yet been proven for Roussolakkos, but has been widely accepted due to the size of the city.

At the 10th International Congress of Cretan Studies in October 2006, Jan M. Driessen and J. Alexander MacGillivray presented to the public the theory of one or more tsunamis as a result of the Thera eruption , making the Minoan city of Roussolakkos too large at the end of SM IA Parts was destroyed. They relied on the excavation findings from buildings 6 and 2, which showed both the ashes of the volcano and the simultaneous destruction of the buildings. In doing so, they compared the marks of destruction with those of the tsunami after the earthquake in the Indian Ocean in 2004 . MacGillivray took the view of a late date of the Thera outbreak around 1500 BC. And a short period of about 40 years for the subsequent late Minoan phase SM I B in Roussolakkos.

In the first decade of the new millennium, graves were discovered and excavated in the area, experimental trenches were dug in certain places and the northern buildings of Roussolakkos were further investigated. Finally, in the 2010s, there were again major excavation campaigns under the name Palace and Landscape at Palaikastro (PALAP). After the geophysical investigations of 2001 and this confirming geophysical work in 2012, corresponding excavation zones of the “palace fields” were defined. The 2013 excavations there did not confirm the assumption of larger palace-like buildings. The deposits found probably originate from a water channel during floods in the direction of Petsophas. The following two excavation campaigns in 2014 and 2015 took place on the plots of Argyrakis (Αργυράκης), Mavrokoukoulakis (Μαυροκουκουλάκης) and Papadakis (Παπαδάκης) southeast of the areas of the Roussolakos archaeological site that are now open to the public. The structures of three buildings (AP1, AM1 and MP1) from phases SM I and SM III were examined with some signs of earlier settlement.

literature

- Robert C. Bosanquet, Marcus N. Death : Archeology in Greece 1901–1902 . In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies . No. 22 . Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, London 1902, p. 384–387 (English, digitized version [accessed March 18, 2018]).

- Robert C. Bosanquet: Excavations at Palaikastro I . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 8 . Macmillan, London 1902, pp. 286–316 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- Robert C. Bosanquet, Richard M. Dawkins and others: Excavations at Palaikastro II . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 9 . Macmillan, London 1903, pp. 274–387 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- Richard M. Dawkins, Charles T. Currelly: Excavations at Palaikastro III . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 10 . Macmillan, London 1904, pp. 192–231 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- Richard M. Dawkins, Charles H. Hawes , Robert C. Bosanquet: Excavations at Palaikastro IV . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 11 . Macmillan, London 1905, pp. 258–308 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- Richard M. Dawkins: Excavations at Palaikastro V . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 12 . Kraus Reprint, London 1971, p. 1–8 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- Robert C. Bosanquet, Gilbert Murray : The Palaikastro Hymn of the Kouretes . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 15 . Macmillan, London 1909, pp. 339–356 (English, digitized version [PDF; 1.3 MB ; accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- Robert C. Bosanquet, Richard M. Dawkins: The Unpublished Objects from the Palaikastro Excavations, 1902-1906 . Macmillan, London 1923 (English).

- Richard W. Hutchinson, Edith Eccles , Sylvia Benton: Unpublished Objects from Palaikastro and Praisos. II . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 40 . Cambridge University Press, 1940, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 38-59 , JSTOR : 30096709 (English).

- L. Hugh Sackett, Mervyn R. Popham: Excavations at Palaikastro VI . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 60 . Cambridge University Press, 1965, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 249-315 , JSTOR : 30103158 (English).

- MH Smee: A Late Minoan Tomb at Palaikastro . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 61 . Cambridge University Press, 1966, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 157-162 , JSTOR : 30103168 (English).

- L. Hugh Sackett, Mervyn R. Popham: Excavations at Palaikastro VII . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 65 . Cambridge University Press, 1970, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 203-242 , JSTOR : 30103217 (English).

- J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett et al .: An Archaeological Survey of the Roussolakkos Area at Palaikastro . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 79 . Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 129–159 , JSTOR : 30103053 (English, digitized [accessed March 16, 2018]).

- J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett, Jan M. Driessen, David Smyth: Excavations at Palaikastro 1986 . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 82 . Cambridge University Press, 1987, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 135-154 , JSTOR : 30103085 (English).

- J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Excavations at Palaikastro 1987 . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 83 . Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 259-282 , JSTOR : 30103119 (English).

- J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Excavations at Palaikastro 1988 . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 84 . Cambridge University Press, 1989, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 417-445 , JSTOR : 30104568 (English).

- J. Alexander MacGillivray, Jan M. Driessen: Minoan settlement at Palaikastro . In: Pascal Darcque, René Treuil (ed.): L'Habitat Égéen Préhistorique (= Bulletin de correspondance hellénique . Volume 19 ). École Française d'Athènes, 1990, ISSN 0304-2456 , p. 395–412 (English, digitized version [accessed March 17, 2018]).

- J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Excavations at Palaikastro 1990 . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 86 . Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 121-147 , JSTOR : 30102877 (English).

- J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett, Jan M. Driessen: Excavations at Palaikastro, 1994 and 1996 . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . tape 93 . Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 221–268 (English, online [accessed December 23, 2018]).

- Jan M. Driessen, J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett (Eds.): Ancient Palaikastro - 1902-2002, An Exhibition to mark 100 years of Archaeological Work . Exhibition Catalog. Hellenic Center, London 2003 (English).

- Carl Knappett, Anna Collar, L. Hugh Sackett, Peter Warren, Victor EG Kenna: Unpublished Middle Minoan and Late Minoan I Material from the 1962-3 Excavations at Palaikastro, East Crete (PK VIII) . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 102 . Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 153–217 , JSTOR : 30245249 (English, digitized [accessed March 23, 2018]).

- Hendrik J. Bruins, Johannes van derpflicht, J. Alexander MacGillivray: The Minoan Santorini Eruption and Tsunami Deposits in Palaikastro (Crete): Dating by Geology, Archeology, 14 C, and Egyptian Chronology . In: Radiocarbon . tape 51 , no. 2 . Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona, 2009, ISSN 0033-8222 , p. 397–411 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- Florence Driessen-Gaignerot: The frieze from the Temple of Dictaean Zeus at Palaikastro . In: Πεπραγμένα Ι΄ Διεθνούς Κρητολογικού Συνεδρίου (Χανιά, 1-8 Οκτωβρίου 2006), Τόμος Α5 . Filologikos Syllogos "O Chrysostomos", Chania 2011, ISBN 978-960-9558-07-5 , p. 425–436 (English, digitized version [accessed March 17, 2018]).

- Seán Hemingway, J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: The LM IB Renaissance at postdiluvian Pre-Mycenaean Palaikastro . In: Thomas M. Brogan, Erik Hallager (eds.): LM IB pottery: relative chronology and regional differences (= Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens . No. 11, 1 ). Danish Institute at Athens, Athens 2011, ISBN 978-87-7934-573-7 , p. 513-530 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 28, 2018]).

Individual evidence

- ^ A b J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Palaikastro . In: Eric H. Cline (Ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean . Oxford University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-987360-9 , pp. 571 (English, excerpt from Google book search).

- ^ A b J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Palaikastro . In: Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Gerald Cadogan, John A. Gifford (Eds.): The Aerial Atlas of Ancient Crete . University of California Press, Berkeley 1992, ISBN 978-0-520-07382-1 , pp. 226 (English, digitized in the Google book search).

- ↑ Catherine Morgan: Palaikastro. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2012, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Αρχαιολογικoί Χώροι: Το Παλαίκαστρο στη Μινωική Εποχή. Palaikastro.com, 2015, accessed March 16, 2018 (Greek).

- ^ Diedrich Fimmen : The Cretan-Mycenaean culture . Teubner, Leipzig and Berlin 1921, sites on the Sporades and Crete: Paläkastro, p. 16 ( digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ a b c Ian Swindale: Palaikastro. Minoan Crete, May 20, 2016, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Palaikastro . In: John A. Gifford, J. Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Gerald Cadogan (Eds.): The Aerial Atlas of Ancient Crete . University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles 1992, ISBN 978-0-520-07382-1 , pp. 226 (English, excerpt [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ a b c d e J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Palaikastro . In: Eric H. Cline (Ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean . Oxford University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-987360-9 , pp. 574 (English, excerpt from Google book search).

- ^ Antonis Vasilakis: Crete . Mystis, Iraklio 2008, ISBN 978-960-6655-30-2 , Palaikastro (ancient dicta), p. 83-84 .

- ↑ Sebastian Zöller: The society of the early "dark centuries" on Crete . Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg 2005, location catalog: Palaikastro Kastri ( digitized , Fig. 45–47 [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ Mark Alonge: The Palaikastro Hymn and the modern myth of the Cretan Zeus. (PDF, 167 kB) Stanford University, December 2005, p. 2 , accessed on March 16, 2018 (English).

- ↑ Jane Ellen Harrison : Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1912, The Hymn of the Kouretes, pp. 1–29 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ Martin Persson Nilsson : History of the Greek Religion . 3. Edition. First volume: The religion of Greece up to the Greek world domination . Beck, Munich 1992, ISBN 978-3-406-01370-6 , Prehistoric times: The afterlife of the Minoan religion, p. 322 ( excerpt [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ Balbina Bäbler: Zeus. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/2, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01487-8 , Col. 782-791, here Col. 788.

- ↑ Strabo : Description of the Earth . Ed .: Albert Forbiger . Hoffmann, Stuttgart 1858, Description of Crete, p. 144, 149 ( 475 , 478 [accessed March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ Joseph Eddy Fontenrose : The Ritual Theory of Myth . University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles / London 1971, ISBN 978-0-520-01924-9 , The Palaikastro Hymn, p. 30 (English, excerpt [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ^ Antonis Vasilakis: Crete . Mystis, Iraklio 2008, ISBN 978-960-6655-30-2 , The Sanctuary and Temple of Dictean Zeus, p. 84 .

- ↑ Otto Kern (Ed.): The inscriptions of Magnesia on the Maeander . Spemann, Berlin 1900, ISBN 978-3-11-084477-1 , Arbitration of the magnets in a dispute between Hierapytna and Itanos, p. 99 ( extract [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ^ Marc Dubin: The Greek Islands (= DK Eyewitness Travel Guide ). Dorling Kindersley, London 2011, ISBN 978-1-4053-6070-8 , Moní Toploú, p. 281 (English, excerpt [accessed on March 20, 2018]).

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis: The Treaties between Cretan Poleis in the Hellenistic Period . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 978-3-515-06827-7 , The historical framework, p. 49–51 ( excerpt [accessed March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis: Greedy Gods, Greedy Cities: Sanctuary ownership and territorial claims in the Cretan treaties . In: Edmond Frézouls, Edmond Lévy (eds.): Ktèma . No. 13 . Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 1988, ISSN 0221-5896 , p. 26 ( digital copy [PDF; 632 kB ; accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis: Sanctuaries of supraregional importance on Crete . In: Klaus Freitag, Peter Funke, Matthias Haake (eds.): Cult - Politics - Ethnos. Supraregional sanctuaries in the field of tension between cult and politics . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-515-08718-6 , The sanctuary of Zeus Diktaios near Palaikastro, p. 204–205 ( digital version [PDF; 1.1 MB ; accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis: The Treaties between Cretan Poleis in the Hellenistic Period . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 978-3-515-06827-7 , The historical framework, p. 55–56 ( excerpt [accessed March 16, 2018]).

- ^ Archaeological Site in Palekastro of Siteia. Ministry of Culture and Sport (Greece), 2012, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- ^ Ernst Pfuhl : Comments on archaic art . In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute . tape 48 . German Archaeological Institute, Berlin 1923, The terracotta reliefs from the sanctuary of Dictaean Zeus in Palaikastro, p. 119 ( digitized version [accessed on March 16, 2018]).

- ↑ Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt : Travels and Researches in Crete . van Voorst, London 1865, Chapter 19, p. 210 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Federico Halbherr : Researches in Crete III: The Præsian Peninsula . In: The Antiquary: A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past . tape 25 . Elliot Stock, London 1892, p. 155 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 19, 2018]).

- ↑ a b c Florence Driessen-Gaignerot: The frieze from the Temple of Dictaean Zeus at Palaikastro . In: Πεπραγμένα Ι΄ Διεθνούς Κρητολογικού Συνεδρίου (Χανιά, 1-8 Οκτωβρίου 2006), Τόμος Α5 . Filologikos Syllogos "O Chrysostomos", Chania 2011, ISBN 978-960-9558-07-5 , p. 425-426 (English, digitized [accessed March 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Stefanos A. Xanthoudidis : Μήτραι αρχαίαι εκ Σητείας Κρήτης . In: Ephēmeris archaiologikē . Athens Archaeological Society , Athens 1900, Sp. 25 (Greek, digitized version ).

- ↑ Stefanos A. Xanthoudidis: Μήτραι αρχαίαι εκ Σητείας Κρήτης . In: Ephēmeris archaiologikē . Athens Archaeological Society, Athens 1900, Πίναξ 3–4 (Greek, digitized version ).

- ^ A b Robert Carr Bosanquet, Marcus Niebuhr Death : Archeology in Greece 1901–1902 . In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies . No. 22 . Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, London 1902, p. 384–386 (English, digitized [accessed March 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Robert Carr Bosanquet: Excavations at Palaikastro I . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 8 . Macmillan, London 1902, pp. 286 (English, digitized version [accessed March 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Robert Carr Bosanquet: Excavations at Palaikastro I . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 8 . Macmillan, London 1902, pp. 288 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Robert Carr Bosanquet: Excavations at Palaikastro I . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 8 . Macmillan, London 1902, pp. 303–305 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 22, 2018]).

- ↑ Stefan Hiller : The Minoan Crete after the excavations of the last decade . In: Fritz Schachermeyr (Ed.): Mykenische Studien . tape 5 . Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1977, ISBN 978-3-7001-0176-5 , The time after the great palaces, p. 192-193 .

- ↑ a b Ancient Sites: Minoan Palaikastro - The excavators. palaikastro.com, 2015, accessed on March 19, 2018 .

- ^ Robert Carr Bosanquet, Richard MacGillivray Dawkins and others: Excavations at Palaikastro II . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 9 . Macmillan, London 1903, pp. 277 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 19, 2018]).

- ^ Robert Carr Bosanquet, Richard MacGillivray Dawkins and others: Excavations at Palaikastro II . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 9 . Macmillan, London 1903, pp. 274 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 19, 2018]).

- ^ Robert Carr Bosanquet, Richard MacGillivray Dawkins and others: Excavations at Palaikastro II . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 9 . Macmillan, London 1903, pp. 279–280 (English, digitized version [accessed March 19, 2018]).

- ^ Richard MacGillivray Dawkins, Charles Trick Currelly: Excavations at Palaikastro III . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 10 . Macmillan, London 1904, pp. 195–196 (English, digitized [accessed March 20, 2018]).

- ^ Richard MacGillivray Dawkins, Charles Trick Currelly: Excavations at Palaikastro III . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 10 . Macmillan, London 1904, pp. 198–202 (English, digitized [accessed March 20, 2018]).

- ^ Richard MacGillivray Dawkins: Excavations at Palaikastro IV . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 11 . Macmillan, London 1905, The Season's Work, pp. 258 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 21, 2018]).

- ^ A b Annual Meeting of Subscribers . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 11 . Macmillan, London 1905, pp. 310 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 22, 2018]).

- ^ Robert Carr Bosanquet: Excavations at Palaikastro IV . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 11 . Macmillan, London 1905, The Temple of Diktaean Zeus, p. 298–305 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 21, 2018]).

- ↑ Richard MacGillivray Dawkins: Excavations at Palaikastro V . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 12 . Kraus Reprint, London 1971, p. 1–8 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 22, 2018]).

- ↑ J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Palaikastro . In: Eric H. Cline (Ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean . Oxford University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-987360-9 , pp. 572 (English, excerpt from Google book search).

- ^ L. Hugh Sackett, Mervyn R. Popham: Excavations at Palaikastro VII . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 65 . Cambridge University Press, 1970, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 203 , JSTOR : 30103217 (English).

- ↑ a b c Stefan Hiller: The Minoan Crete after the excavations of the last decade . In: Fritz Schachermeyr (Ed.): Mykenische Studien . tape 5 . Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1977, ISBN 978-3-7001-0176-5 , The time of the Minoan palaces, p. 164-165 .

- ↑ L. Hugh Sackett, Mervyn R. Popham: Excavations at Palaikastro VI . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 60 . Cambridge University Press, 1965, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 249 , JSTOR : 30103158 (English).

- ↑ Palaikastro. Quentin Letesson, 2014, accessed March 24, 2018 .

- ^ Günter Neumann: Epigraphische Mitteilungen . In: Kadmos . tape 25 , volume 2. de Gruyter, 1986, ISSN 1613-0723 , p. 172 (English, excerpt [accessed on March 26, 2018]).

- ^ Costis Davaras: A Minoan Pottery Kiln at Palaikastro . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . tape 75 . Cambridge University Press, 1980, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 115 , JSTOR : 30103011 (English).

- ↑ J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: Palaikastro . In: Eric H. Cline (Ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean . Oxford University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-987360-9 , pp. 572 (English, excerpt from Google book search).

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Reviewed Work: The Palaikastro Kouros: A Minoan Chryselephantine Statuette and Its Aegean Bronze Age Context . Book review. In: American Journal of Archeology . tape 106 , no. 2 . Archaeological Institute of America, 2002, ISSN 0002-9114 , pp. 326 , JSTOR : 4126258 (English).

- ↑ a b Alexander MacGillivray: Labyrinths and Bull-Leapers . In: Archeology . tape 53 , 2000, pp. 54 (English, digitized ).

- ↑ Christian Bauer: Goddess Twilight: The End of a Myth: Even among the Minoans, women did not rule - this is indicated by the discovery of a noble Zeus figure. Focus Online , September 3, 2007, accessed March 4, 2017 .

- ↑ Balbina Bäbler: Zeus. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/2, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01487-8 , Col. 782-791, here Col. 788.

- ↑ Michael J. Boyd, Ian K. Whitbread, Sandy MacGillivray: Geophysical Investigations at Palaikastro . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . No. 101 . Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISSN 0068-2454 , pp. 89–134 (English, abstract [PDF; 746 kB ; accessed on March 26, 2018]).

- ^ Seán Hemingway, J. Alexander MacGillivray, L. Hugh Sackett: The LM IB Renaissance at postdiluvian Pre-Mycenaean Palaikastro . In: Thomas M. Brogan, Erik Hallager (eds.): LM IB pottery: relative chronology and regional differences (= Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens . No. 11, 1 ). Danish Institute at Athens, Athens 2011, ISBN 978-87-7934-573-7 , p. 518 (English, digitized version [accessed on March 26, 2018]).

- ^ Matthew Haysom: Palaikastro, Mesonisi. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2002, accessed March 27, 2018 .

- ^ Matthew Haysom: Palaikastro. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2005, accessed March 27, 2018 .

- ↑ Don Evely: Palaikastro. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2010, accessed March 5, 2018 .

- ^ Caroline Thurston: Palaikastro. N. Mavrokoukoulaki plot. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2009, accessed March 27, 2018 .

- ^ Caroline Thurston: Palaikastro. G. Mavrokoukoulaki plot. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2009, accessed March 27, 2018 .

- ↑ Catherine Morgan: Palaikastro. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2008, accessed March 27, 2018 .

- ↑ Don Evely: Palaikastro. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2010, accessed March 27, 2018 .

- ↑ Catherine Morgan: Palaikastro. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2013, accessed March 27, 2018 .

- ^ Catherine Morgan: Palace and Landscape at Palaikastro. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2014, accessed March 27, 2018 .

- ^ John Bennet: Palace and Landscape at Palaikastro. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2015, accessed March 27, 2018 .

Web links

- Palaikastro: Roussolakkos (Settlement). In: Digital Crete: Archaeological Atlas of Crete. Foundation for Research and Technology-Hellas (FORTH), Institute for Mediterranean Studies(English).

- Αρχαιολογικός Χώρος στο Παλαίκαστρο Σητείας. Ministry of Culture and Sport (Greece), 2012, accessed 16 March 2018 (Greek).

- Sitia: Archaeological Places. Sitia Development Organization, 2016, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- Alexandros Roniotis: Minoan city of Rousolakos. CretanBeaches! 2018, accessed March 16, 2018.

- Ian Swindale: Palaikastro. Minoan Crete, May 20, 2016, accessed April 15, 2018 .

- Archaeological Site of Palaikastro. Greek Travel Pages, 2017, accessed March 16, 2018 .

- Palaikastro Archaeological site. Interkriti, accessed on March 16, 2018 .