City fortifications of Worms

The city fortification of Worms , which was built to protect the city of Worms since Roman times , in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period, consisted in the final stage of two wall rings with around 60 towers and eight gates in the inner and nine gates in the outer wall. The fortification was never taken.

history

Romans

The city of Worms (civitas Vangionum / Borbetumagus) was not walled until the end of the Roman Empire , around 360 AD, when the threat of attacks from the right bank of the Rhine became latent. This date is mainly secured by an extensive excavation on the east side of the fortification, where about 40 m were uncovered and archaeological findings prove this. Before that, the settlement hadn't had a wall. There is no archaeological evidence for an earlier Roman city wall, which is widely suspected in older literature, but numerous assumptions have sprouted.

The Roman wall ran south along today's Andreas and Wollstrasse. To the east, a little west of Fischmarkt and Bauhofgasse, the original edge of the edge towards the Rhine. Here the wall was proven by an excavation and part of the evidence was kept open in an archaeological window so that it can be seen here. The course of the northern section, however, is not known and is assumed to be on a line between Ludwigsplatz and north of Paulusstrasse. Roman masonry is also visible in the western city wall. It is probably not the Roman city wall, but a part of the building of the adjoining Roman temple area that was used as a secondary building in the Middle Ages .

middle Ages

The Roman wall ring was sufficient for the needs of the city until the High Middle Ages. It was repeatedly repaired - even later. The oldest surviving written mention of the wall comes from 897.

On the inside of the eastern wall, facing the Rhine, there was the Salier castle in the High Middle Ages , who began their career here as a family of counts.

It was not until the 10th century that the wall was extended to the south, where the wall now ran along today's Willy-Brandt-Ring and Schönauer Straße. In the vicinity of this expansion or because of the threat from the Normans who pushed up the Rhine, but - in contrast to the Hungarians - never reached Worms, a wall building code was created that is attributed to Bishop Thietlach . It regulated who had to contribute to the construction and maintenance of the wall. In addition to the other city dwellers, this also included the Frisians , who settled in the northeastern area of the city and were active in long-distance trade. The wall section there was subject to their care. Building and maintaining such a city fortification was expensive. Various groups of townspeople and also potentially protection seekers from unsurfaced places in the surrounding area were obliged to guarantee this, who had the right to seek protection behind the walls in the event of war. That didn't always work smoothly. The wall often showed structural damage and the refusal of individual obligated parties to make their contribution is also attested.

The second expansion took place under Bishop Burchard at the beginning of the 11th century. After a phase in which the structural maintenance of the walls had been neglected, he arranged for the repair and the northern section of the Roman wall was extended by the wide arch of a new wall that ran from the western edge of today's Ludwigsplatz, along Martinsgasse, Judengasse and the Bärengasse was replaced. In the east it was connected to the existing Roman wall that protected the east side of Worms. The written sources that have been preserved do not give any reliable clues as to the specific appearance of the facility at that time. Some of them are also contradictory. Every now and then there is also talk of a wall without its relationship to the wall being explained or clarified.

In the Annales of Lampert von Hersfeld , written in 1078/1079, he reports that the citizens of Worms sided with Heinrich IV in the conflict . The Worms fortifications are mentioned as excellent and impregnable. Since the Bishop of Worms, Adalbert II , had sided with the opponent Henry IV, the citizens saw an opportunity to ally themselves against the city lord with the king. This put troops into the city and thus effectively took over the city rule. With the gradual withdrawal of the royal military, he also left the city's citizens with control of the city walls, a process that took place in the first quarter of the 12th century. Since then, the citizenship has had sovereignty over the city's defense and the facilities that serve it. News from the years 1116 and 1234/35 also report that the city was fortified from a military point of view.

The third extension of the city wall - now under the direction of the city - was erected shortly before 1200 to the east, where the wall was moved forward by 70 m, about the thickness of a building block, towards the Rhine, to the east. The dating was dendrochronologically secured after an archaeological excavation in 1987 : built-in wooden posts date from the year 1196. This would also be the oldest absolute historical dating available for the city fortifications. But because the point where the samples were taken also allows for alternative interpretations, this dating is questioned by others and the construction of the wall is set in the second third of the 13th century due to criteria of art history .

Originally the simple wall with battlements ran around the city. She was about 6,30 m high. The movement of the guards and the military along the wall served an alley that ran directly behind the wall. The Judengasse was an exception. The northern row of houses was built directly to the rear of the city wall, which led to conflicts between the defense interests of the city and the interests of the landowners. This extension of houses to the wall is unique in medieval Worms and structurally resulted in the city wall here on the field side [!] Showing the remains of Romanesque , Gothic and Renaissance windows .

The wall was raised to about 8 m - probably in the 14th century - after black powder and firearms appeared. Broad arches were set behind the wall. A wooden battlement , which was largely open to the city, ran on top of it. A reconstruction can be seen in the area of the Nibelungen Museum and is accessible. In the area of Judengasse, where the houses were built directly onto the city wall, this meant that the battlements had to be led through the house in some buildings, for example in No. 39, the house "Zur Büchs" (also : "Guggenheimhaus"), on the second floor, which was only removed during a renovation in 1980.

For 1201 it is recorded that the men of the Jewish community were also armed and obliged to defend the city wall.

In 1234 part of the wall at the inner Andreastor collapsed.

For 1272 there is a message that - at least parts - of the city wall were in a ruinous state. In 1321 the city council issued an ordinance on the construction and maintenance of the moat.

In 1491 the master builder Jakob Bach from Ettlingen was recommended by the Worms council of the city of Frankfurt, where he completed the cathedral tower . This makes it likely that he previously carried out construction work for the city of Worms and its fortifications.

Early modern age

From 1515 to 1518 Franz von Sickingen besieged the city. The fortification held up.

During the Thirty Years' War , the city opened the gates to the Imperial (1620 and 1635–1642), Swedes (1632), Lorraine (before 1631 and 1642–1644) and French (1644–1650) each on a contractual basis. The city and its fortifications were largely spared from damage. Only the Swedes demolished the outer fortifications and the suburbs in 1630.

The log of an inspection of the inner wall is available for 1686. It records what the city council representatives found in the towers of the inner wall. The condition of the military equipment, especially the guns, was checked . Much was still usable, but some of the equipment was also defective.

In 1688, based on an agreement with the city council, French troops occupied the city during the War of the Palatinate Succession . They first destroyed the outer ring of the fortifications from February 1689 and from March 1689 began to destroy the inner wall ring as well. Martinspforte, Neutor and Leonhardstor were blown up. After the destruction of the city on May 31, 1689, but at the latest after the withdrawal of the French troops in June 1689, the inner wall was left partially destroyed, around 1150 m of the approximately 2750 m long wall were completely destroyed. The damage to the fortifications amounted to 800,000 Reichstaler .

The medieval city wall was meanwhile militarily senseless in view of "modern" artillery and the remains were useless for defense. However, it was still used for legal, police and tax delimitation from the surrounding area and was therefore repaired. This was no longer done by the citizens themselves, but the council commissioned craftsmen to do it. Not much is known about the scope of these repairs. B. It is doubted whether the burned, wooden parts of the battlements were restored. During the reconstruction phase from around 1700, the wall could be used as a back wall for buildings. Windows were broken into there. The encircling battlements disappeared except for small remains. In sections the wall also served as a quarry, e.g. B. for the construction of the Holy Trinity Church 1710–1715. A section of the outer wall was used to expand the Jewish cemetery , while a section of the ditch in front of it served the Hessian Ludwig Railway in the 19th century as a route for its route from Mainz to the state border at Bobenheim in Bavaria , which was opened in 1853.

Modern times

Victor Hugo , who also visited Worms as a traveler on the Rhine in 1838, also reports ironically and disappointedly about the remains of the city fortifications that he found:

A few decrepit pieces of wall from which window sockets stare, a few stumps of the wall, either completely overgrown and suffocated by ivy, or transformed into apartments of good citizens of Worms, with white window curtains, green shutters or hanging vines and garden houses instead of battlements, loopholes and kennels . Misshapen ruins of a round tower, which stood out from the wall in an easterly direction, seemed to be the remains of the old Niedeck tower […] We reached the city […] where there was originally a gate and now there was only a hole. Two poplars on the left, a dung heap on the right .

Until the last quarter of the 19th century, the city sold sections of the wall as building land or to residents and removed gate systems in order to gain wider openings for the growing traffic. Parts of the southern section of the wall were demolished at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1874 the city council issued a price list for the sale of parts of the city wall. This was countered by efforts to preserve the historical substance: in 1838 the demolition of the gate tower was prevented on the grounds that it was a historical monument. In 1851, the city council stipulated that valuable antiquities found during demolition work on the city wall should be returned to the city, and in the first decade of the 20th century, parts of the wall were restored as historical monuments.

The moat of the inner wall in the west and partly in the north was redesigned into a park in the second half of the 19th century, then in the west - inaugurated in 1868 - the monumental Luther memorial was placed in the green area. Woog and Gießen on the east side increasingly silted up. Building land was later created here.

In 1907, under the head of the building department and mayor Georg Metzler, the remaining wall was secured and redesigned, also in terms of monument preservation . The existing building was renovated, but the new Andreastor in the south and the Raschitor in the north were also broken through the wall in order to meet modern traffic requirements.

In 1920, parts of the moat in the area of the green area on the west side of the inner city fortifications were filled. Up until the 1960s, parts of the wall were torn down when they stood in the way of rebuilding.

With the onset of modern monument preservation in the 1970s, as manifested in the "European Year of Monument Protection 1975", increasing attention was also paid to the preservation of the remaining architectural evidence of the city wall in Worms. From the 1980s onwards, more archaeological investigations were added.

A structure as large and used for many centuries as the Worms city wall represents a great challenge for research and monument preservation alike .

History of the outer wall

In the 12th and 13th centuries the walls were also built on a larger scale ("Martinsvorstadt", later "Mainzer Vorstadt"). In 1268 the northern settlement on Mainzer Straße, the main axis to Mainz and to the north, is still secured by a pole fence, not a wall. It is not clear when the outer wall was built. The oldest written record that has been preserved is from 1279. Repeated reports about the cost of building the wall from the 13th century are now interpreted as evidence of repairs to the existing inner wall ring. There is documentary evidence of the towers of the outer wall from the middle of the 14th century, but before 1500 this outer wall is "only very isolated". The north-south extension of the outer wall ring was about 2200 m, in east-west direction it was about 800 m.

Knowledge of the history and appearance of the outer wall ring is less than that of the inner one. The construction work was also less complex than that of the inner wall ring and today there are hardly any structural evidence left.

In the 16th century the outer wall was reinforced with 11 bastions and received a rampart and a moat. A bird's eye view of the city of Worms as it was before it was destroyed in 1689, drawn by Peter Hamman at the end of the 17th century, shows the closed wall ring that surrounded the city in the north, west and south. Only in the east, towards the Rhine, was there no second wall.

As early as 1630, during the Thirty Years War , Swedes damaged the outer fortifications and the suburbs. In 1688, French troops also occupied the neutral city of Worms as part of the War of the Palatinate Succession . From February 1689, the outer wall ring was laid down, including more than 40 towers.

Although militarily useless, attempts were made by the city to restore the outer wall. Since there was no money for this, the city gave out adjacent urban land for agricultural purposes on the condition that the manager also rebuilt the adjacent wall. The measure had only moderate success.

Landwehr

In front of both wall rings there was a Landwehr that was pushed far into the district .

organization

Construction

From the late Middle Ages onwards, the city had paid construction workers who were supported by day laborers who were subordinate to the “Allment and Building Authority”. This was directed by the older and younger builders who were specialists. These in turn were under the supervision of two councilors with the titles "Oberbauherr" and "Unterauherr". The "Allment- und Bauamt" operated a municipal building yard, the oldest mention of which dates back to 1499 and which was also responsible for maintaining the wall.

The supervision of the structural condition of the wall was the responsibility of both the builders and the councilors. Wall and ditch sections were assigned to individual councilors for life. In addition, the city gave apartments in the towers to “proper bachelors”. Instead of rent, they were obliged to maintain the towers and stairs structurally and the guns stationed there ready for action and to reinforce the guard.

The city reformation of 1499 - a summary of the Worms city law - also contained a number of provisions for the structural protection of the city wall. Because there were numerous attempts by residents to use the wall structurally for their needs and to change it, be it through extensions or superstructures or even the breakthrough of doors.

guard

There is different information about whether walls and towers were always occupied in peacetime, but the opened gates were always guarded. Individual wall sections and towers were assigned to the 17 guilds for defense, some of which also attached their guild signs. All the towers were constantly armed with guns. The permanent wall guard was given up after 1689 at the latest.

In order to keep the dangers associated with the open city gates as low as possible, only the four main gates - and only as long as there was daylight - were usually always open, the others only when there was seasonal demand, especially for agriculture. The main gates were: Martinspforte, Rheintor, Leonhardspforte and Andreaspforte.

Opening and closing the gates was a cumbersome process. The gates were so heavy that the guard needed help. Since the keys were kept with the mayor at night for security reasons, they first had to be picked up by the gate closers there in the morning. There were special gate closers for each gate. They came from the ranks of the young citizens who lived near the gate in question. They then also helped the guard open and close the gate.

The open gate was guarded by the day watch. At their head was the porter, a paid city official. In addition to the military-police guarding the gate, he had the task of making sure that no one left the city without being able to show the receipt for the unpaid money . At night it was his job to forward mail that arrived at the city gate. The actual guard consisted of the "journeymen from the beat" and comprised three or four men. The day watch was paid. Each of the 17 guilds in Worms had to provide one. The conversion to mercenaries , as happened in many other cities, did not take place in Worms until the end of the 18th century. In addition to the actual security duty, the “journeymen” were also responsible for delivering services to the mayor when it was questionable whether someone was allowed to enter the city.

The night watch was organized differently: In the 15th century, a guild provided 14 men for three consecutive nights who had to do this without pay. They had to go through the gates and make sure that they were all properly locked. There was also patrol in advance of the fortifications , especially at night.

After the completion of the outer wall, only the gates of the outer wall were occupied in times of peace.

The city wall was not only used for defense. Rather, it was also a customs border . From the 16th century, taxes and duties were levied on consumer goods imported into the city, and export bans were monitored. So the name of the head of the gate guard changed from “gatekeeper” to “gatekeeper”.

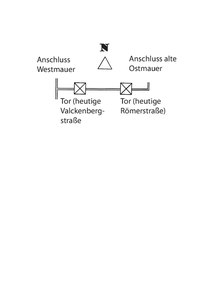

Inner wall ring before the 13th century

The southern city wall was rebuilt in the 10th, and the east end of the 12th century, shifted outward compared to the existing Roman wall.

Old east wall

The first east wall, abandoned around 1200 or in the 13th century, historically consisted of two sections: A northern one, which was built on the occasion of the new construction of the northern fortifications at the beginning of the 11th century. It connected to the Roman wall further south. Both together formed the eastern city wall until the 13th century.

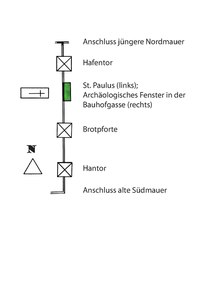

In the area of the St. Paulus monastery , archaeological investigations on a larger scale were possible on this first east wall in the years 1987–1989. An “archaeological window” has remained open on site.

Old port gate

In the old east wall there was a city gate to the Rhine harbor at the point where the Judengasse, Bärengasse and Sterngasse meet today. Since this is only documented and not proven by an archaeological finding, its exact position remains open. It also remains to be seen whether the remains of the wall that came to light in this area during an excavation in 1987 can be assigned to the gate.

Bread gate

Nothing is known about the bread gate. Its oldest surviving mention comes from a forged document dating back to 1080 in the 12th century. It got its name from the Brotgasse which opens there. The bread gate is possibly identical to the "salt gate" (Brotgasse and Salzgasse ran parallel here). This makes it likely that it belonged to the old east wall, as the new east wall was built at the end of the 12th century at the earliest.

Others assign the "bread gate" to the area of the Rhine gate in the newer east wall. One of the two partially preserved sandstone reveals, the gates that were subsequently broken into the wall, between the Rheinpforte and Mayfels, then belonged to it.

Hantor

The Hantor / Hanport was a passage at the south end of the wall. The name comes from the Hagenstraße which flows here, which was temporarily shortened to "Hanstraße" in colloquial language. The gate was down the street. It has not yet been proven archaeologically, but a Roman origin seems plausible. The substance of the city was destroyed in 1689, and it was not until 1788 that the city council had the gate demolished and the demolished material auctioned.

Old south wall

The course of Andreasstraße and Wollstraße corresponds to the course of the old wall from Roman times, which was replaced from the 10th century by the new wall positioned further south. There is only a few evidence of the sections of the Roman-early medieval wall that are now at the rear, as the demolition material was rebuilt elsewhere. However, there are some archaeological findings.

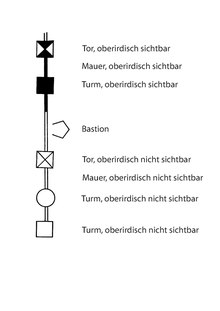

Inner wall ring after 1200

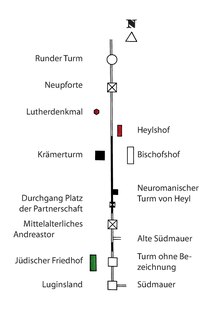

In the final stage, the inner city wall consisted of a simple wall, which was reinforced at intervals by 27 towers, had eight gates and was subsequently provided with a battlement. It was about 2500 m long. All 26 towers were rectangular, except for one: the round tower (not preserved) on the west side. Also all towers - except one - were full towers, only the binding tower was a shell tower . The inner wall was preceded by a ditch that was very deep, especially to the west. Because of the slope of the terrain towards the Rhine, it only ran in the eastern half of the water, in the south roughly to the Leonhardstor, in the north to the Martinstor. The western half was dry.

The assignment of individual wall sections or parts to specific epochs or building measures is extremely problematic and has only been done in a few sections to this day.

Along the inner wall ring there are 11 places in addition to the masonry still visible today, where archaeological excavations have taken place.

The following individual descriptions start in the north and continue clockwise.

North side

The wall is built on the south, west and north sides from precisely placed quarry stone blocks made of sandstone . The northern section of the wall runs in a wide semi-arch, the eastern part of which forms the wall on Judengasse. From the beginning of the 11th century, a Jewish settlement center developed here - following the settlement of the Frisians. The houses in Judengasse border directly on the back of the city wall. In the house at Judengasse 39, the house "Zur Büchs", the battlements ran through the building, a situation that was not resolved until the 1980s. For the house at Judengasse 37, the city wall to today's Herta-Mansbacher-Anlage was redesigned around 1900 into a new Romanesque (second, rear) facade (not preserved).

The easternmost area of the northern section already belongs to the eastern urban expansion of the late 12th century. Remnants of the foundations - not visible from the outside - are preserved in the house at Bärengasse 34.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the northern section of the wall was heavily historicized and the "Rashi Gate" was also broken down.

The following were or are set in the wall on the north side:

Martin Gate

The Martinspforte in the northern section of the inner city wall secured the entry of the important trade route from and to Mainz into the city. It was badly damaged in 1689 and demolished in the 18th century, as was a customs gate built in the same place in the 19th century.

In 1903/04, a replica was created with the construction of the “Martinspforte” house , whose shape was based on the former gate tower, but was rotated 180 degrees and roughly halved in height.

In 1989 an archaeological excavation took place in the area of the city wall adjoining it to the east. Here, two sections of the wall are still preserved and visible in the house walls.

Brick tower

The brick tower, based on structural features from the Hohenstaufen era, stands in the northern section of the wall, east of the Martin gate. It was named after an upper floor made of bricks, which has not been preserved today.

After it was damaged in the city's destruction in 1689 and during air raids in 1945, a piece of it was removed in the 1970s “to ensure that an apartment behind it could be lit”. Today it is only two-story and serves as the roof terrace of the neighboring apartment. Originally it was 22 m high. A door was broken into the historical substance and a platform staircase was introduced. Measures that are highly dubious in terms of monument preservation.

Breakthrough at the Herta Mansbacher facility

The breakthrough of the Herta-Mansbacher -anlage is a short street created after the Second World War between the Berliner Ring and the Judengasse . It is not designed in relation to the city wall.

Executioner's or torture tower

The executioner's or torture tower was roughly level with Synagogenplatz. It was demolished in the 1950s when the house at Judengasse 33 was rebuilt. The foundations of the tower were archaeologically uncovered again later. It was found that it is identical to the "Mayfels" tower, which dates it to the end of the 1200s.

Execution Tower

The executioner's tower stands in the northern section of the wall, was probably built in the Hohenstaufen era and has a cellar. Originally it was 22 m high. The tower was blown up and damaged in 1689, but rebuilt for the construction of the Raschitor in 1907/08. The wall on the city side is medieval masonry, while the walls on the field side date from after 1689. The tower was only rebuilt up to the height of the battlements. Since the breach of the wall by the "Raschitor", the executioner's tower has formed the western "gate tower" of the gate.

Judenpforte

The Judenpforte was in the area of Bärengasse. The oldest written evidence with this name for this city gate ("Porta Judeorum") dates from the 12th century. This is in a forged document, but dated to 1080. The gate tower was 22 m high.

During the Swedish occupation of the city in the Thirty Years War, a ravelin was thrown in front of the gate in 1632.

During the reconstruction after 1689 the gate was walled up. After the opening of the ghetto, the gate was opened again, also known as the “Hamburger Tor” in the 19th century.

Raschitor

The Raschitor is a modern breakthrough through the wall that took place in 1907/08. The remaining wall was renovated under the construction department and mayor Georg Metzler , but in addition to the Raschitor in the north, the new Andreastor in the south and the opening for Herzogenstrasse in the east were created as new connections through the wall in order to meet modern traffic requirements.

The wall continues east here. After about 100 m, at the southwest corner of the crossing Bärengasse, the beginning of the first east wall from the 11th century can be seen.

Kopsort

Kopsort (also: Capsort) was the northeast corner tower of the inner city fortifications. It had a small bay window and was 23 m high.

This is also where the outer ring of the wall began, which ran north from here.

East Side

The kink of the wall, where the Kopsort stood and where the north and east sections meet, is called the "Friesenspitze". The name comes from the Frisians who settled in this area in the 10th century and operated long-distance trade.

The course of the wall was created here on the occasion of a city expansion towards the Rhine at the end of the 12th or 13th century. The construction took place in one go with walls, buttresses and supporting arches for the battlements and took some time. This section of the wall was laid out on a regular basis - before later renovations changed it: three towers, a gate, three towers, a gate and another three towers. The towers protruding from the wall on the field side are particularly striking. The wall facing the Rhine also had a representative character. Around 1300 the wall was raised and the battlements were placed on arcades presented inside .

This section of the wall appears to be the most completely preserved today. However, at the beginning of the 19th century, 9 of the original 11 towers on the Rhine front were still preserved. Today there are still two of them. And these have only been preserved because nobody wanted to buy the site because of the poor, damp building site. Later, the section at the citizen and gate tower was added to the restoration of individual sections of the city wall in 1907, including the loopholes and the battlements. The representations by Peter Hamman from the 17th century were used as the basis for the heavily damaged upper areas. What can be seen today is largely a historicist building in the upper areas . Three construction phases can be identified in the medieval-early modern building fabric. The two younger ones each raised the wall a little. The two older ones ended with battlements , the youngest provided the wall with the covered battlement .

From 1999 to 2001 the Nibelungen Museum was built on the inside of the wall, between the citizen tower and the gate tower - including the city wall and its battlements . This was preceded by considerable concerns from the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments and the attempt to prevent the project with a referendum , but this failed due to the quorum . In January 2020, renovation work began in the area between the Herzogenstrasse passage and the gate tower .

The Kopsort described above was or is set in the wall on the east side. It is followed to the south by the internals:

Anabaptist Tower

The Anabaptist Tower stood on the Wallstrasse 3 property. The origin of the name is unclear. In 1527 all Anabaptists were expelled from Worms. As late as 1720, consideration was given to using it as a city prison.

While the Anabaptist Tower was not preserved, the corresponding section of the wall is well preserved and can be seen particularly well from Rheintorgasse . Individual views are also possible from Wallstrasse, which runs parallel to it. However, the city wall forms the rear boundary of the property and is therefore difficult to access.

Rhine gate

The Rhine gate is a small, Gothic passage through the wall in the course of the street Große Affengasse , the arch of which on the city side is still original. It was used for pedestrian traffic when the Rhine gate was closed.

Rheinpforte

The Rheinpforte or the Rheintor was one of the passages through the eastern wall to the Rhine and the harbor, following a gate that used to be in the Mayfels tower. Here taxes were levied on consumer goods imported into the city. The Rhine gate was Rheinstrasse 29. The roof of the gate tower was wearing a roof turret and had four corner towers. A tower blower was stationed here as a guard.

The medieval Rhine gate was auctioned for demolition on May 15, 1822, and the material was used to reinforce the banks of the Rhine. However, remains of the foundation in the cellar of a house on the corner of Rheinstrasse and Rheintorgasse are said to have been preserved.

In front of the tower was a wooden-covered bridge over the Woog. The foundations of the bridge were archaeologically excavated in 2009, partially conserved, preserved and accessible. The bridge was protected on the Rhine side by another small gate building. From here the path continued towards the Rhine and crossed the Gießen , another body of water, again with a wooden-covered bridge. This crossing was guarded by another gate tower, the Gießenpforte, through which the path led.

The Rheinpforte gave its name to the Rheintorgasse.

Immediately next to the Rhine gate was the municipal building yard, which also served to maintain the walls. The armory, on the other hand, where valuable equipment was stored, was on Römerstrasse.

Significant parts of the wall section between the Rheinpforte and the Mayfels tower located next to the south have been preserved parallel to Haspelgasse. From there there is a pedestrian passage through the wall. On the Rhine side, a path runs through a small green area with a good view of the outside of the city wall. Since the 1990s, the various construction phases and heights of the wall have been highlighted with plaster. On the city side, houses for poor people were built into the arches that support the battlements in the 18th century, which are only about four meters deep. These were renovated and modernized in the period after the Second World War.

Mayfels

The foundations of the Mayfels were created on the occasion of the eastern city expansion towards the Rhine. The tower protruded from the line of the wall on the field side and was the most important city gate on the Rhine side until the construction of the neighboring Rhine gate as the “Rhine gate”. Humpback blocks typical of the Staufer era were built here. It is known from written records that the tower on its east side, facing the Rhine, was painted with a picture of Emperor Henry IV at the end of the 15th century , who certified Worms as a town in 1074. The accompanying text referred to the event and also contained a vow of loyalty from the citizens. When the picture was taken is unknown.

The ruins of the tower still stood after the Second World War . A partially preserved Romanesque archway on the inside showed that a gate had been converted into a tower here. Its rising masonry was demolished in the 1950s to make way for new buildings. In 1987 the foundations were uncovered again in an archaeological dig. A depot with 150 stone cannonballs of different calibers was also discovered. A skyscraper was then erected on the area with almost the cubature of Mayfels, which externally takes on the shape of the tower, as Peter Hamman depicted it in the 17th century.

Immediately south of the Mayfels, the city wall had a passage for a drainage canal. Here, the course of the city wall was also marked in a modern way in the pavement and the wall has been preserved beneath the ground surface as the wall of the underground car park of an apartment building.

Locksmith tower

The locksmith's tower was also called the "tower at the building yard". It was named after the fact that individual guilds were responsible for towers and / or wall sections, here the locksmiths. Schlossergasse, on the other hand, is in the city center.

Eisbach outlet

Immediately to the north next to the begging vogt tower was the outlet of the Eisbach , which in this section was referred to as "Unterbach". It ran through the city, was important as process water for various water-intensive trades from the tanners to the operation of mills and flowed again from the walled city area towards the Rhine.

Begging Vogt Tower

The Beggar Vogtturm was immediately north of Petersstrasse. Its remains were still there after the Second World War and were demolished in the 1950s in order to place a block of flats there, an "urban planning sin".

Passage Herzogenstrasse

The Herzogenstraße passage is a new passage in the wall created in 1907 to cope with modern traffic. It is one of the breakthroughs made during this period, as are the Rashi and Andrea gates. It was designed historicizing . Its abrupt northern end came about when, after the Second World War, the city wall had to give way to “an architecturally mindless and incorrectly placed apartment building”.

Citizen Tower

The citizen tower , also built on the occasion of the eastern expansion of the city, is identical to the "Mayfels". and protrudes from the wall on the field side. There are only small loopholes here , backwards, towards the city, but large windows. The humpback blocks typical of the Staufer era were built here. The tower has four floors. It was not until 1988 that the battlements were converted into windows and a tower helmet was put on.

Fisherman's gate

The Fischerpforte is an ogival passage for pedestrians. It did not take on its current form until 1907. The passage is also known as the “Luther Gate”, but has nothing to do with Martin Luther or his stay in Worms for the 1521 Reichstag .

Gate tower

The gate tower (also: "Fischerpforte", not to be confused with the aforementioned Fischerpforte) was built on the occasion of the eastern expansion of the city. It served as one of the gates to the Rhine. Directly in front of him was the “Woog”, a dammed pond over which the fishing bridge led. This was secured on the Rhine side by an additional small external gate.

The tower protrudes from the wall on the field side, the battlements on the city side lead around the building on the outside. The humpback blocks typical of the Staufer period were used here. The tower corners on the Rhine side are reinforced by two buttresses each. The ground floor is a gate hall with an ogival entrance. There are only small loopholes towards the Rhine, towards the city towards the back, but large windows. The tower had a total of four floors with wooden ceilings. There was a fireplace in the room on the first floor. The current tower helmet dates from 1987.

When the city was destroyed in 1689, the tower burned down. It was also restored in 1907. The tower was preserved because it belongs to the section of the wall that was considered very poor building land due to its proximity to the Rhine. The corresponding plots of fortification proved to be unsaleable. In 1838, the municipal council campaigned for the preservation of the tower - quite contrary to its otherwise practiced policy. An air raid shelter was built here during the Second World War . When it was demolished after the war, the arches of the gate were badly damaged.

Marktmeisterturm

The market masters tower has not been preserved.

Schmitturm

The smith tower follows south. The name was derived from the fact that individual guilds were responsible for towers and / or wall sections, in this case the forge. In the drawing by Peter Hamman, which shows the city of Worms after it was destroyed in 1689, the tower appears intact and still supports its roof.

Between the present-day properties at Weihergasse 8 and 9, remains of the wall at the height of one storey have been preserved. They can be seen from the street.

In Weiherstrasse and Wollstrasse, the course of the above-ground city wall, which is no longer preserved above ground and which crossed today's roads here at almost a right angle, is marked in the paving of the road surface.

Binding tower

The binding tower was the hinge between the southern and eastern walls. It was open to the city and 23 m high. In the drawing by Peter Hamman, which shows the city of Worms after its destruction in 1689, the tower is mainly damaged on the city side, the roof is missing, but the wall on the field side seems to be largely at the original height.

Remnants of the tower are now preserved behind the houses Pfauenpforte 9 and Jahnstraße 10. This is also where the outer city wall began, which ran further south from here, while the inner wall continued to the west.

South side

The "Luginsland" tower formed the hinge between the western and southern walls, and the binding tower between the southern and eastern walls. The remnants of the eastern part of this section were cleared away in the 20th century. However, there are some archaeological findings here, including where the course of the wall can no longer be traced in the cityscape due to modern developments. In the western section, from Valckenbergstrasse, the south wall still stands in considerable parts. The Andreasstift is located directly behind the wall, leaning against it . The back wall of the southern cloister wing forms the city wall and also the outer wall for the two floors of the museum above. There is a second row of arcades on the first floor, which rests on the lower one, and only then was the battlements. Four of the arcades have been preserved. All window openings through the wall in this area date from the 20th century. Three buttresses placed in front of the city wall support the building. Extensive construction studies and renovation took place here in 2012.

Part of this section of the wall next to the Christoffelturm collapsed on the night of May 14th, 1907, because the abutment of the last pillar of the defensive arcade had been partially removed and replaced by a wooden frame. But that had become rotten. The city wall had to be rebuilt here.

The Luginsland wine grows on the grave-side area in front of the Andreasstift - one of the smallest vineyards ever. The filling of this vineyard is almost as high as the interior ground floor of the museum.

The binding tower described above was set in this southern section of the wall, which follow or follow to the west:

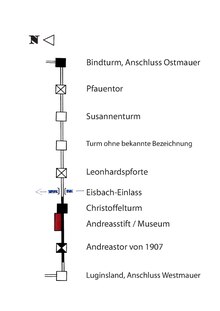

Peacock gate

The oldest surviving written record of the peacock gate dates from 1035. The peacock gate (porta pavonis) was the easternmost gate in the south wall. According to the excavation findings from 1993, it was shifted a few meters from the axis to the east in the street Pfauenpforte at its confluence with the intersection of Schönauer Straße / Pfauentorstraße. From here the route led to Maria Münster (Nonnenmünster), a Cistercian convent, and on towards Speyer. This is where the name comes from: "Pfauenpforte" is a corruption of "Frauenpforte".

The gate tower was rectangular and had two buttresses at the corners of the outside. He was with portcullis and drawbridge equipped and decorated to the outside with a small turrets and the inscription "Specula Vangionum". In the woodcut by Sebastian Münster , this inscription even appears as the name of the gate. The gate tower had a height of 29 m. The gate is shown badly damaged in a drawing by Peter Hamman, which he made while looking south at the city of Worms, which was destroyed in 1689.

Today the gate is no longer preserved, but was discovered in 1993 during an archaeological dig.

Susann Tower

According to the excavation findings of 1993, the Susannenturm was located east of Römerstraße about 20 meters north of its confluence with Schönauer Straße. It was placed on the trench side in front of the wall and originally had a height of 21 m. On the drawing by Peter Hamman, which he made while looking south at the city of Worms, which was destroyed in 1689, the tower can no longer be made out in the rubble of the wall, so it is probably completely destroyed.

Nothing remains of the tower above ground today. However, it was found during an archaeological excavation on a property on the corner of Schönauerstrasse and Römerstrasse. There, its outline was reproduced in the pavement after the excavation findings , but this is no longer preserved today (2019) and means that the public memory of the position of the tower has disappeared.

Tower with no known name

Another tower - for which no name has been passed down and which has not been preserved as a building - is not reproduced on the drawing by Peter Hamman, which he made of the city of Worms, which was destroyed in 1689. The tower can no longer be made out in the rubble of the wall, so it was completely destroyed. In 1990 it was detected during an archaeological excavation in the area of Schönauerstraße 11. and uncovered again on the occasion of construction work in 2019. He jumped about ten feet from the wall.

Leonhard Gate

The Leonhardspforte was one of the southern city gates for the connection to Speyer and has not been preserved. It is attested under various names. It is mentioned for the first time in 1259 under the name “nova porta” (new gate). It must not be confused with the Neutor in the western city wall. So it was built into the wall shortly before this oldest surviving mention. Over time, traffic to and from the south increasingly shifted from the Pfauentor here. This also led to the name "Inner Speyer Gate".

The gate tower was 23 m high. During the Swedish occupation of the city in the Thirty Years War, a ravelin was thrown in front of the gate in 1632. In the drawing by Peter Hamman, which he made of the city of Worms, which was destroyed in 1689, he shows the eastern wall of the gate tower collapsed.

The moat in front of the gate led - coming from the direction of the Rhine - water roughly as far as here. It was surmounted by a bridge from the gate, the Leonhard Bridge.

When the French troops began to tear down the inner wall in March 1689, the Leonhardstor was also destroyed.

Eisbach inlet

At the Leonhardspforte there was a passage through the inner wall for the Eisbach into the city. Presumably this was done on the west side of the gate tower. Another passage a little east of the tower could have belonged to a mill. To get into the city, the Eisbach had to cross the city moat. This happened on a wooden footbridge. On the drawing by Peter Hamman, which he made of the city of Worms, which was destroyed in 1689, this construction is shown as still fully functional! The Eisbach continued underground on the inside of the wall.

Christoffelturm

The Christoffelturm (also: Christophelturm ) is only medieval in the lower area. It was 23 m high and was badly damaged in 1689. The upper floors were not added again until the 1920s. Like the neighboring Andreasstift , the tower is now part of the Worms City Museum .

Andrea's Gate (1907)

Today's Andreastor is right next to the Andreasstift. It was created in 1907 as a passage through the southern section of the wall for the increasing traffic. During the construction work, the existing city wall turned out to be so dilapidated that it had to be completely removed in this section and rebuilt together with the newly created gate.

The following section of the wall up to the Luginsland is depicted as completely destroyed by Peter Hamman. Building studies have shown, however, that it still has, to a large extent, older structures in the rising masonry. The presentation by Hamman is then exaggerated.

Luginsland

The "Luginsland" tower was positioned diagonally to the adjoining walls, the south and west walls of the inner city fortifications, which converged at right angles, and formed the southwest corner and the hinge between the two wall sections. The tower was 33 m high. According to a local legend, Emperor Friedrich II had his son, Heinrich (VII), who rebelled against him, locked up here in 1235. On a drawing by Peter Hamman, which he made of the city of Worms, which was destroyed in 1689, he shows the blown up tower, whose city-side wall has been preserved, but whose field-side wall has completely collapsed. The tower was later rebuilt. It was only demolished when the Villa Werger was built in the 1890s. The corner tower of the villa reproduces the situation in the same place.

The "Luginsland" tower gave its name to the street of the same name.

West side

The west side of the inner city wall has only a few towers. It is also built from precisely placed quarry stone blocks. Above ground nothing remains of the western part from the connection to the northern wall up to the level of Stephansgasse, but the line of the wall can still be seen on the building boundary to the ring of buildings (the former city moat). Many houses used the wall as a foundation facing west. The only and so-called “round tower” of the inner wall ring used to stand here.

Subsequently, along the Lutherring, the oldest parts of the wall were preserved. They stand on Roman foundations from the 2nd century. However, it is not certain whether these are parts of a city wall from this time or masonry that originally served another building. On the one hand, a pointed moat, as was common in Roman fortifications, is said to have run in front of it. On the other hand, the wall is interpreted here as part of the building of the adjoining Roman temple area. The oldest rising masonry comes from the Frankish-Carolingian period. It is the oldest surviving medieval architectural monument in Worms. In the garden of the Heylshof , which adjoins the wall on the city side, it serves as a romantic closure of the park to the west. A grotto with the Hercules fountain was built in here in the late 19th century and a neo-Romanesque turret was introduced inside [!]. To the south of the park, between the cathedral and the city wall, the nation's place (today: the place of partnership) was created in 1933/1935 by demolishing the farm and coach house buildings of the Heylshof . He uses the inside of the city wall as a closure to the west. The existing inside arches of the wall were blocked and two round arched passages were broken.

The Luginsland described above was or is set in the western wall, followed by installations to the north:

Unmarked tower

Between the medieval Andreastor and the Luginsland, opposite the entrance to the Holy Sand , there was another tower whose name has not been passed down.

Medieval Andrea Gate

The medieval (inner) Andreastor was in the southern section of the western city wall. It was destroyed in 1689. This medieval gate is not to be confused with the new Andreastor of the same name from 1907 in the southern city wall.

Place of partnership

The Place of Partnership (then: Place of the Nation ) was created in the 1930s. The city wall to the complex in front of it was broken through with two arched openings.

Neo-Romanesque turret

As an elevated tank to supply the neighboring villa of the industrialist Cornelius Wilhelm von Heyl zu Herrnsheim , the Heyl's Hof , and above all its park with water, a neo-Romanesque turret was built on the inside [!] Of the city wall at the end of the 19th century so that it also served as a peripheral decoration for the park. The turret is now integrated into the design of the partnership square with a heavily modified roof.

Chandler Tower

The Krämerturm (also: "Neidturm" or "Mauerturm") was one of the few towers on the west side of the wall and the only one between Andreastor and Neupforte. It stood at the point of the wall behind which the bishop's court was. This did not suit the bishop, Johann II von Fleckenstein , and he obtained a construction freeze in 1411, so that the tower could only be completed in 1424, when the relationship between the bishop and the city relaxed temporarily. The fact that the motive for the construction of the tower was the curiosity of the citizens of Worms to look into the bishop's garden and annoy him is a nice story, but nowhere is it proven.

The tower was freely presented to the wall in the moat without touching it. Its stump has been preserved in the area of the Lutherring park. The corners consisted of hewn blocks made of red sandstone , the remaining walls were made of rubble stones. The tower was 17 m high. The bishop's court and tower were destroyed by the French in 1689.

In the 18th century, the bishop built an orangery with two turrets here and also included the city wall. The city protested, but could not prevent it.

Inner New Gate

The inner “new gate” was also called the “new gate”. It was on the corner of Adenauerring and Obermarkt, in front of the houses Obermarkt 13 and 15, and is said to have been laid out in the middle of the 13th century. Its gate tower was 34 m high, making it the tallest tower on the inner wall. In the 17th century it carried a high roof with four small turrets at the corners. Immediately north of the gate, the city dance house was built on the wall, which was demolished in 1880.

During the Swedish occupation of the city in the Thirty Years War, a ravelin was thrown in front of the gate in 1632 . From March 1689, the French military that had occupied Worms in the course of the War of the Palatinate Succession began to tear down the inner wall. The Inner Neutor was destroyed in the process. When the city was rebuilt after 1700, a simple gate was built here, which was again demolished in 1866. Its foundation is marked in the paving and with a plaque embedded there.

Round tower

Unlike all of the other 25 towers of the inner city wall, which were all rectangular, this one was a round tower. It was roughly level with the memorial for the fallen of World War II . On Peter Hamman's bird's eye view, which shows the city before it was destroyed in 1689, he wears a Welsche hood . On a drawing he made of the city of Worms, which was destroyed in 1689, only the foundations of the tower can be seen. Today nothing of it has survived above ground either.

Then the Martin Gate followed again in a north-easterly direction (see above).

Outer wall

The information on the outer defensive ring is far more sparse than on the inner city wall. From location information that are received in documents and that refer to the wall, it can be concluded that the outer wall was built in the second half of the 1360s, but at least in the second third of the 14th century. Other authors, based on general considerations, assume the 13th century. It is also likely that construction dragged on for decades.

The structural design of the walls of the outer wall ring was much less complex than the inner wall ring: It was a simple wall, without battlements, which was reinforced with mostly small, but not exclusively round towers. The gate systems, on the other hand, were designed more representative and thus also served the self-portrayal of the city to the outside world and had six own archways. But the city's growth stagnated as early as the 14th century. During the entire time that the outer wall ring was in existence, it never succeeded in settling the area it encompassed even in an even approximately closed manner. Most of the areas here were used for horticulture and agriculture.

The course described below begins at the Bindturm, the southeast corner tower of the inner fortification, and goes clockwise and from south to north:

Cattle gate

The cattle gate was a simple gate and secured access to the citizen pasture. The gate was between today's houses at Pfauentorstrasse 8 and 9.

Two or three towers of unknown names

Two or three towers of unknown names protected the southern section of the outer wall along the Rhine. It does not yet exist in Sebastian Münster's depiction. Most of the authors proceed from Peter Hamman's account. Instead of Wormbß, as it did in 1631 before the Swedish ruin of the Vorstätt […] , that is, two towers remained . The northern or both northern towers were small round towers, the southern one of the few square towers in the outer wall. Between the square tower and the Aulturm there was an arched opening in the wall, from which drainage flowed out.

Aulturm

The Aulturm, also called “Die Aul” for short, is called “Nideck” by Sebastian Münster. But only the upstream bulwark bore this name. The name "Aul" or "Owl" was the name of a pot shape that roughly corresponded to the appearance of the tower.

The Aulturm protected the southeast corner of the outer fortifications. The tower was round and had a brick, domed roof. In terms of design, it was intended for the stationing of artillery . Judging by its structural shape, it is said to have been built around 1450. He was surrounded by his own bastion.

When the city was destroyed by the French in 1689, this tower was the first building of the city fortifications to be blown up . It was damaged in the process, but did not topple over at first. It was only possible to destroy it on the second attempt.

There was a bulwark between the Aulturm and the New Speyer Gate, but no more a tower.

New Speyer gate

The gate was in the area of the intersection of today's Speyerer Straße with the Mainz – Mannheim line , south of the tracks. The historic Speyerer Straße was the main axis from Worms to the south and already existed in Roman times. The oldest surviving written mention of the gate comes from 1258.

The New Speyer Gate was a gate tower decorated with a roof turret on a square floor plan. It replaced the much more elaborate Old Speyer Gate to the west.

Old Speyer Gate

The Alte Speyerer Pforte was in the area of the intersection of Speyerer Straße with the Mainz – Mannheim railway line, north of the tracks. Here Speyerer Strasse left the city in the direction of Speyer .

It was a double gate with two flanking round towers. There was another bastion in front of it. For unknown reasons, the gate was abandoned, walled up and replaced by the New Speyerer Porte.

Three towers of unknown names

The further course of the wall was reinforced by three more small round towers, the name of which has not been passed down.

Inlet of the Eisbach

The inlet of the Eisbach in the outer wall was protected by a flanking square tower. The entrance itself was through a simple arch.

Gate of the mill of the Nonnenmünster monastery

In this area, the mill of the Nonnenmünster monastery was built into the wall. There was an additional door in the wall that gave access to the squeegee . The key was entrusted to the conductor of the monastery, who had to swear a special oath to the city council for handling the key .

Michael Gate

The Michaelspforte was a relatively unspectacular gate in the southwest corner of the outer wall. It was only opened when necessary, but was important for agricultural traffic.

In front of the Michealspforte in 1515, all residents of the city threw an additional fortification in view of the threat posed by Franz von Sickingen - only the clergy did not participate. A bastion was in front of the gate in the 17th century.

Southwest corner tower

There is no archaeological or other evidence of the Roman origin - at least of the foundations - of the following tower, presumed in the older literature. This tower formed the southwest corner of the outer wall ring.

Three towers of unknown names

This is followed by three towers of unknown names. The wall between the northernmost of these towers and the outer Andreastor has been preserved as the elevated eastern area of the historic Jewish cemetery . After the outer defensive line was abandoned, the cemetery was expanded to include the rampart from the beginning of the 18th century. The trench in front of the rampart, which the Hessian Ludwigsbahn used from 1853 for the route of its Mainz – Bobenheim (state border) line , today's Mainz – Mannheim line, was also preserved .

Outer Andrea Gate

The outer Andreaspforte served the road towards Alzey . There was a bastion in front of it, which had a third gate.

Four towers of unknown names

Another four round towers of unknown names follow. The three southern ones were in the area of Das Wormser . Another bastion lay in front of the next north. According to the city map by Peter Hamman, which depicts the city before it was destroyed in 1689, the two middle towers of these towers had one-story accompanying buildings on each side along the wall.

Outer new gate

The Outer Neutor was located in today's Wilhelm-Leuschner-Strasse between houses 29 and 30. According to Peter Hamman's illustration, it was flanked by a rectangular tower, the passage and the associated archway were north of the tower. A bridge led over the ditch in front, which was secured on the field side with another gate. That was about where the prince's pavilion of the reception building of Worms main station stands today.

Four towers of unknown names

This was followed in a northerly direction by a section with four towers of unknown names. According to the city map by Peter Hamman, which depicts the city before its destruction in 1689, they had two-story wing structures on each side, parallel to the wall. One of the towers stood in the Siegfriedstrasse / Renzstrasse area.

The section of the wall running here was used as its eastern wall in the 19th century when the new cemetery was created (today: Albert-Schulte-Park ).

Neuhauserpforte

The Altmühl- or Neuhauserpforte was in the area of the roundabout Gaustraße / Altmühlstraße. The gate was walled up after an incident in 1408.

A tower of unknown name

In the further course another tower followed with a name unknown today.

Mainz Gate

The Mainzer Pforte stood in the area of today's intersection of Mainzer Straße and Liebfrauenring and secured the old trading route in the outer wall ring leading from the Martinspforte to Mainz.

The gate tower, which was destroyed in 1689, became the model for the bridge tower on the left bank of the Rhine (still preserved today) shortly before the turn of the 20th century when the Ernst Ludwig Bridge was built.

Four towers of unknown names

This is followed by four towers of unknown names, with the approximate positions: near Mainzer Straße, where Bergadistraße joins Liebfrauenring Liebfrauenring 21 and north of Liebfrauenkirche. In front of the latter was the Liebfrauenbuckel, the north-easternmost bastion of the outer wall. According to the city map by Peter Hamman, which depicts the city before its destruction in 1689, all towers had two-story wing structures on each side, parallel to the wall. None of the towers have survived.

New tower

The Neuturm formed the mounting dernordöstlichen corner of the outer boundary wall, was right on the Rhine and was especially designed imposing. It was destroyed in 1689.

Golden gate

The "Gültenpforte" was immediately south of the new tower. It is said to have borne its name because of a particularly rich decoration. However, according to all the historical images that have been preserved, it was an extremely simply designed gate without any decoration. It is widely known in the literature that it served as a representative reception for important guests arriving on the Rhine. The only example that has been cited again and again is the arrival of Empress Bianca Maria , wife of Emperor Maximilian I. The Güldene Pforte was bricked up in 1719.

Two towers of unknown names

Two more towers follow along the wall. The northern one was in the area of today's port station and was a round tower, like most of the smaller towers of the outer ring. In Sebastian Münster, around 1550, in Braun / Novellanus / Hogenberg: Description ., Before 1574, and also in Matthäus Merian , around 1650, the northern of the two towers is depicted as a ruin or unfinished. It is only about as high as the top of the wall and has no roof. The southern one stood roughly in the area where Friedensstrasse joins Hafenstrasse and was - in contrast to most of the other towers on the outer wall - square. According to the city map by Peter Hamman, which depicts the city before its destruction in 1689, he had two-story wing structures on each side, parallel to the wall. The towers have not been preserved.

Goose gate

The Gänspforte was at the confluence of Friesenstrasse (formerly: Fischergasse) in the Berliner Ring. It was used to drive cattle to the pastures in front of the wall. All depictions in front of Peter Hamman show a gate with a passage in an east-west direction. Peter Hamman, on the other hand, shows a gate building rotated by 90 degrees with a passage in a north-south direction. It remains to be seen whether a renovation took place here or whether Peter Hamman made a mistake.

Two towers of unknown names

Two more towers of unknown names followed. One stood in front of today's house at Nibelungenring 27, the other on the corner of today's Wallstrasse and Berliner Strasse.

Sebastian Münster's view from around 1550 shows only a tower with a square floor plan in this section of the wall. Braun / Novellanus / Hogenberg: Description , shows no tower at all in this wall section. Peter Hamman's plan, which depicts the city before it was destroyed in 1689, shows two square towers. In his drawing of the Rhine front of the city of Worms, however, the tower in front of the house Nibelungenring 27 is shown as a small round tower. Most authors assume this representation. The towers have not been preserved.

Trench passage

Immediately before the outer wall at Kopsort , the north-eastern corner tower of the inner city fortifications, rejoined the inner wall, it had a passage for the trench that ran along in front of the inner wall.

Upstream bastions

In the 16th century the outer wall was reinforced with 11 bastions . It was in response to an increasingly powerful artillery. They were ramparts that protruded from the wall at right angles . On the enemy side, they predominantly had two walls ( facen ) that were also at right angles to one another , the rear throat that was drawn in was - with the exception of three - occupied by one of the gates or a tower. Clockwise, from south to north, these were the bastions:

- Nideck in front of the Aulturm, a Viereckschanze

- Bastion between the Aulturm and the New Speyer Gate (without tower)

- Old Speyer Gate

- Michael Gate

- An unmarked bastion, just in front of the Luginsland tower of the inner wall (no tower)

- Outer Andrea Gate

- Bastion south of the new gate

- Bastion east of the Neuhauser Pforte (without tower)

- Mainz Gate

- Liebfrauenbuckel, the northeasternmost bastion of the outer wall. A round tower used to stand in its center. Today, the bastion is the only one that can still be seen in the area, north of the street “Liebfrauenring”, in the vineyard of the Valckenberg estate .

- Neuturm, a square bastion next to the tower

Further fortifications and defenses

The Nonnenmünster monastery to the south, in front of the city gates, was fortified by the city in the middle of the 13th century, a measure that was, however, part of a political dispute within the city between the bourgeois authorities and a guild-like artisan group directed against them. The fortification therefore had to be removed again.

The city of Worms was able to equip warships. The majority of the evidence for this comes from the 13th century and relates to foreign war trips. The ships could also be used for defense in an attack from the Rhine.

Worth knowing

- The preserved parts of the city fortifications of Worms are cultural monuments due to the monument protection law of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate .

- Before it was destroyed in 1689, French officers measured the wall and made plans that are still to be kept in Paris today. Further documents on the Worms fortifications are suspected to be in the war archive in Stockholm.

- In Herta Mansbacher-conditioning is on a playground , the city wall with its eight goals reduced recreated as a game device. This is an attempt to convey the structure of the inner city wall to children. The "gates" are there, however, created as shell towers , which the originals never were.

- In the 1990s there was a "city wall festival".

swell

literature

in alphabetical order by authors / editors

- KH. (= Karl Heinz Armknecht): The Martin Gate . In: Worms monthly mirror from December 1968, p. 25f.

- KH. (= Karl Heinz Armknecht): The Neidturm . In: Worms monthly mirror from December 1970, p. 4f.

- Karl Heinz Armknecht: The Worms city walls . In: Der Wormsgau 9 (1970/1971), pp. 54-65.

-

Gerold Bönnen (ed.): History of the city of Worms . Theiss, Stuttgart 2005. ISBN 3-8062-1679-7 , therein:

- Gerold Bönnen: The heyday of the high Middle Ages: From Bishop Buchard to the Rhenish Bund (1000–1254) , pp. 133–179.

- Gerold Bönnen: Between Bishop, Empire and Electoral Palatinate: Worms in the late Middle Ages (1254–1521) , pp. 193–261.

- Gerold Bönnen and Joachim Kemper: The spiritual Worms: Abbey, monasteries, parishes and hospitals up to the Reformation , pp. 691–734.

- Otfried Ehrismann: Worms and the 'Nibelungenlied' , pp. 824–849.

- Mathilde Grünewald : Worms from the prehistoric epoch to the Carolingian era , pp. 44-101.

- Thomas Kohl and Franz Josef Felten : Worms - city and region in the early Middle Ages from 600–1000 , pp. 102–132.

- Gunter Mahlerwein: The imperial city of Worms in the 17th and 18th centuries , pp. 291–352.

- Fritz Reuter : Between reaction and Hessian urban order (1852–1874) , pp. 441–478.

- Fritz Reuter: The Leap into Modernity: The “New Worms” (1874–1914) , pp. 479–544.

- Fritz Reuter: Warmasia - the Jewish Worms. From the beginning to the Jewish Museum of Isidor Kiefer (1924) , pp. 664–690.

- Irene Spille and Otto Böcher: Building history and architectural monuments , pp. 735–792.

- Hellmuth Gensicke: Contributions to the description of the city of Worms in the High Middle Ages . In: Der Wormsgau 3 (1951-1958), pp. 49-63.

- Wolfgang Grün: The city wall of Worms . Stadtarchiv Worms , Worms 1998. ISBN 3-00-002765-3

- Wolfgang Grün: Defensive Worms. 5. The city wall: monument, document, scale. 1) Old Wall - New City . In: Worms monthly mirror from August 1982, pp. 5-8. [quoted: Grün, August 1982]

- Wolfgang Grün: Defensive Worms. 5. The city wall: monument, document, scale. 2) Renewal measures - a civic commitment in Worms . In: Wormser monthly mirror from September 1982, pp. 53–57. [quoted: Grün, September 1982]

- Mathilde Grünewald: The new dates of the inner Worms city wall and the eastern urban expansion . In: Stadtarchiv Worms (ed.): Festschrift for Fritz Reuter on his 60th birthday . Worms 1990. Without continuous page counting. Without ISBN.

- Mathilde Grünewald: New theses on the Worms city walls . In: Mannheimer Geschichtsblätter NF 8 (2001), pp. 11–44.

- Mathilde Grünewald: Late Roman Worms. Excavations at the collegiate church St. Paul in Worms (III.) . In: Der Wormsgau 20 (2001) [special print with its own page number], pp. 7–25.

- Mathilde Grünewald: Under the pavement of Worms. Archeology in the city . Josef Fink, Lindenberg 2012. ISBN 978-3-89870-754-1

- Walter Hotz: Defensive Worms. 4. Art history of the city fortifications. 1.) From Roman times to the Hohenstaufen . In: Wormser monthly mirror from May 1982, pp. 5–12. [quoted: Hotz, May 1982]

- Walter Hotz: Defensive Worms. Art history of the city fortifications. 2) Late Gothic and Renaissance towers and gates . In: Wormser monthly mirror from June 1982, pp. 5-11. [quoted: Hotz, June 1982]

- Walter Hotz: Defensive Worms. Art history of the city fortifications. 5) Destruction, Baroque Restoration, and Decline . In: Wormser monthly mirror from July 1982, pp. 19–24. [quoted: Hotz, July 1982]

- Friedrich M. Illert: Before the end of the fortified city fortifications . In: Der Wormsgau 2 (1941), p. 312f.

- Heribert Isele: The defense system of the city of Worms from the beginning to the end of the 18th century . Masch. Diss. Heidelberg [1951?].

- Monika Porsche: City Wall and City Development. Investigations into the early city fortifications in the medieval German Empire . Wesselkamp, Hertingen 2000. ISBN 3-930327-07-4

- Fritz Reuter: Peter and Johann Friedrich Hamman. Hand drawings by Worms before and after the city's destruction in 1689 in the “War of the Palatinate Succession”. Besseler, Worms 1989. ISBN 3-925518-05-3

- Fritz Reuter: City walls and defense towers through the ages . In: Wormser monthly mirror from February 1982, pp. 5-7.

- Fritz Reuter: Defensive Worms. 2. Staufer wall and late medieval expansion . In: Worms monthly mirror from March 1982, pp. 5-8.

- Fritz Reuter: Defensive Worms. 3. Towers, walls and battlements . In: Worms monthly mirror from April 1982, pp. 5-8.

- Erich Schwan: The street and alley names in medieval Worms = The Wormsgau. Supplement 1. City Library, Worms 1936.

- Irene Spille: Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany . Cultural monuments in Rhineland-Palatinate. Volume 10 (City of Worms). Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft , Worms 1992, ISBN 978-3-88462-084-7

- Olaf Wagener and Aquilante de Filippo: The Worms city wall - New findings on dating and development as well as a report on building research on the city wall in the area of the Andreasstift . In: Der Wormsgau 30 (2013), pp. 19–57.

Historical illustrations

sorted by year of publication

- Sebastian Münster : Cosmographey . Hencicpetrina, Basel 1572, pp. DCXCIII-DCXCVI. [Representation of Worms from the east, i.e. the Rhine side, around 1550].

- Georg Braun, Simon Novellanus and Franz Hogenberg: Description and contrafacture of the most prominent place in the world . Heinrich von Ach, Cologne 1574. Plate between pages 35 and 36. Worms City Archives: Dept. 214 No. 1499.

- Matthäus Merian : Topographia Palatinus Rheni et Vicinarum Regionum . Hoffmann, Frankfurt 1645, plate between p. 96 and p. 97.Worms City Archives: Dept. 217 No. 1495.

- Anonymous: Fortress plan of the city of Worms. View from the north. Drawn in 1622 for the Upper Rhine campaign of Count Ernst von Mansfeld

-

Peter Hamman , 1690–1692:

- Instead of Wormbß like the same in 1631 before the Swedish ruin of the Vorstätt [...] remained . (Pen drawing). Frankfurt am Main, 1691.

- [ View of the city of Worms as it was before 1689 from the east (Rhine front) ] (pen drawing). Frankfurt am Main, 1691.

- [ View of the city of Worms after the destruction in 1689 from the south ]

- [ View of the city of Worms after the destruction in 1689 from the north ]

- Individual drawings of Martinspforte, Pfauenpforte, Mainzer Tor and Neuturm.

Remarks

- ↑ The older local research, on the other hand, assumed - without evidence - an extensive Roman wall (Porsche: Stadtmauer , p. 57f; Armknecht: Die Wormser Stadtmauern , p. 55; Friedrich M. Illert: Die Reichsbedeutung der Stadt Worms. Reference to the Geographical location of the city and its effects . In: Der Wormsgau 2 (1939), pp. 197-220 (210f)). When opposing archaeological findings arose in the 1930s, these were suppressed by the “prevailing opinion”, which led to the transfer of the employee who had digged up these “unpopular” results (Grünewald: Neue Thesen , p. 11f). Mathilde Grünewald draws "the conclusion that there is nothing of it [the Roman wall], but that it persists as a myth" (Grünewald: Neue Thesen , p. 16).

- ↑ So wanted z. B. in 1272 the knights who were wealthy in the city refuse to contribute (Bönnen, in: Bönnen (ed.): Zwischen Bischof , p. 204).

- ↑ That a letter of protection for the Jewish community of King Heinrich IV. From the year 1090 secured this privilege is mentioned again and again in the literature. The text of the certificate does not provide that (Grünewald: Neue Thesen , p. 29).

- ^ According to Armknecht: Die Wormser Stadtmauern , p. 58, all six inland gates were destroyed.

- ↑ For example, Bönnen, in: Bönnen (ed.): Zwischen Bischof , p. 252f, completely dispenses with the depiction of the outer wall ring in the map “Worms around 1500”.

- ↑ The name has nothing to do with Hagen von Tronje , but with a nobleman of the same name who had an estate here in the High Middle Ages (Schwan: Die Straßen- und Gassennamen , p. 43f).

- ↑ DIVO HENRICO IV. ROME. REGI AUGUSTO VANGIONES IMMORTALES LAUDES DEBERE NULLO AEVO NEGABUNT / The Worms will never deny that they owe incessant praise to the immortalized Henry IV Roman King and Augustus (Emperor) (Armknecht: Die Wormser Stadtmauern , p. 61).

- ↑ Haspelgasse 2.

- ↑ “Schmitturm” is spelled with two “t” in the literature, which is mostly older and therefore obliged to use the old orthography . I'll treat this as a proper name and leave it at that.

- ↑ In front of the Weiherstraße 9 building.

- ↑ In front of the Wollstrasse 60 building.

- ↑ It concerns the area of today's stairwell in the Museum Andreasstift (Wagener / de Filippo: Die Wormser Stadtmauer , p. 23).

- ↑ “Lookout of the Worms” (so: Armknecht: Die Wormser Stadtmauern , p. 60) or “Wangionenwarte” (so: Hotz, May 1982, p. 12).

- ↑ Braun / Novellanus / Hogenberg: Description , do not represent a tower in this wall section.

- ↑ According to Hotz, June 1982, p. 8, the Mainzer Pforte is said to have even been a model for both bridge towers.

- ↑ See: Armknecht: Die Wormser Stadtmauern , p. 62, note 53.

- ↑ See: Armknecht: Die Wormser Stadtmauern , p. 59, note 32.

Individual evidence

- ^ Green: Die Stadtmauer , p. 4; Hotz, May 1982, p. 6.

- ↑ Grünewald: Late Roman Worms ; Porsche: City Wall , p. 59f.

- ↑ Grünewald in Bönnen (ed.): Geschichte der Stadt Worms , p. 79; Grünewald: Neue Thesen , p. 13. Insofar not applicable: Spille: Denkmaltopographie , p. 13, 40.

- ↑ See: Armknecht: Die Wormser Stadtmauern , pp. 54–58.

- ↑ Grünewald: Neue Thesen , p. 18, describes their "reconstruction" itself as "thought structure".

- ↑ Grünewald: Under the plaster , p. 42.

- ↑ Grünewald in Bönnen (ed.): Geschichte der Stadt Worms , p. 95.

- ↑ Grünewald in Bönnen (ed.): Geschichte der Stadt Worms , p. 161; see. Reconstruction in Grünewald: Under the plaster , p. 13.

- ↑ Grünewald: Spätrömisches Worms , p. 25.

- ^ Wagener / de Filippo: Die Wormser Stadtmauer , p. 20; Porsche: City Wall , p. 66.

- ↑ Kohl / Felten in Bönnen (ed.): Worms , pp. 109, 121.

- ↑ Grünewald in Bönnen (ed.): Geschichte der Stadt Worms , pp. 95, 161.

- ↑ Kohl / Felten in Bönnen (ed.): Worms , p. 130.

- ↑ Kohl / Felten in Bönnen (ed.): Worms , p. 130.

- ^ Reuter: City walls and defense towers , p. 7; one of these groups was the Jewish community (Bönnen, in: Bönnen (Hg.): Zwischen Bischof , p. 209).

- ↑ Bönnen, in: Bönnen (ed.): The bloom time , p. 166.

- ↑ Bönnen, in: Bönnen (ed.): The bloom time , p. 137.

- ↑ Grünewald in Bönnen (ed.): Geschichte der Stadt Worms , pp. 95, 161.

- ^ Wagener / de Filippo: Die Wormser Stadtmauer , p. 20; Grünewald: New Theses , p. 28.

- ↑ Bönnen, in: Bönnen (ed.): The bloom time , p. 144.

- ↑ Isele: Das Wehrwesen , p. 3.

- ^ Wagener / de Filippo: Die Worms city wall , p. 21.

- ↑ Grünewald in Bönnen (ed.): Geschichte der Stadt Worms , p. 92; Kohl / Felten in Bönnen (ed.): Worms , p. 161; Spille / Böcher: Building History , p. 756.

- ↑ Grünewald: The new data , p. 2; Porsche: City Wall , p. 82.