storm Division

The Sturmabteilung ( SA ) was the paramilitary fighting organization of the NSDAP during the Weimar Republic and, as a police force, played a decisive role in the rise of the National Socialists by using violence to shield their meetings from groups of political opponents or by obstructing opposing events. Because of their uniformity with brown shirts from 1924 onwards, the troops were also called "brown shirts" . In the run-up to the seizure of power in 1933 , the organization devoted itself, in addition to propaganda, to street fighting and attacks on social democrats, communists and Jews. Conflicts with state power were carefully avoided.

In the initial phase of the Nazi state after the seizure of power , Hermann Göring , the Reich Commissioner for the Prussian Ministry of the Interior , appointed the SA as " auxiliary police " as the employer of the Prussian police . After SS units had murdered the top management of the SA in the so-called Röhm Putsch in mid-1934 , it lost a lot of its importance in the further period of National Socialism .

After the unconditional surrender in 1945, like the NSDAP and SS , it was banned and dissolved by the Control Council Act No. 2 .

history

The history of the SA can be divided into three historical stages: the early phase from 1920/21 to 1923, then the rise to a mass organization and from 1934 as an organization in the Nazi state.

Beginnings of the organization and name change

The first police force was increasingly deployed in "hall battles" in January 1920 as room protection ( SS for short ); it consisted mainly of members of various volunteer corps and some members of the Bavarian Reichswehr . The group was initially founded as a gymnastics and sports department in November 1920, and renamed Sturmabteilung (SA) on October 5, 1921.

When the German Workers' Party (DAP) held its first mass events in January 1920 , the necessity of having its own security service quickly became clear, as was the case with other parties. On November 12, 1920, the watchmaker Emil Maurice , whose Jewish origin was unknown to Hitler at the time, founded a "gymnastics and sports department" for the party. After Hitler received dictatorial powers in his party in July 1921, the security service developed into a party force that served to keep him in power.

From this hall protection, the later Sturmabteilung ( SA for short ) developed over several steps as a pure thug troop for provoked clashes with left-wing parties (especially the KPD ), which often led to brutal street fights.

Hitler set up a new protection force of the party leadership called Sturm-Staffel , whose abbreviation was again SS and which consisted of a few members of the Freikorps who remained in the NSDAP. This storm squadron took over the function of the party-internal stewardship . In 1923, Hitler formed his personal bodyguard , the Adolf Hitler strike force , from particularly aggressive members of this storm squadron .

After a particularly brutal battle in the hall between the National Socialists and members of the KPD , the members of this storm squadron and the still unnamed majority of the uniformed free corps and thugs (with the exception of Adolf Hitler's raiding party ) were officially renamed by Hitler on November 4, 1921 as Sturmabteilung . The new name referred to a military combat tactic developed by Willy Rohr during the First World War to overcome trench warfare. The SA, which was then divided into 21 groups and around 300 men, was not only represented with its own units in Munich, but also in Freising, Landshut and Bad Tölz.

The SA was banned three times - on November 23, 1923, on April 13, 1932 and on October 10, 1945 - and was legalized again twice: on February 16, 1925 and on June 14, 1932. As a result of the Hitler-Ludendorff- coup banned the NSDAP and its organizations. In order to circumvent this ban, the SA was designated as a frontbann from April 1924 to February 1925 .

After the seizure of power in January 1933, only the short names ( acronyms ) "SA" and "SS" were in use. The SA and SS existed as nominally separate organizations until the SA leadership was eliminated in mid-1934.

Originated in military associations until the SA was banned from 1923–1925

The gymnastics and sports department became a catchment basin for former members of the resident brigades, which were dissolved in June 1921, and of the former Oberland Freikorps. Ernst Röhm , who is networked with the Reichswehr and the Freikorps, took over the establishment of the party's own security service . As a member of the NSDAP and an active captain and general staff officer at the infantry leader of the VII Bavarian Reichswehr Division, he was the link between the right-wing military associations and the Reichswehr. From former members of Mine Throwing Company 19 of the former Bavarian Army , he formed the party's first hall protection . Former members of the Ehrhardt Marine Brigade , which was disbanded in April 1920, served as commanders . On August 3, 1921, Hermann Ehrhardt von Röhm was first appointed as a guide; However, the latter delegated the task to Lieutenant Hans Ulrich Klintzsch on August 8th . Klintzsch was arrested in early September 1921 in connection with the murder of Matthias Erzberger . Until Klintzsch was released in early 1922, Emil Maurice took over the management again. As a so-called military association, the SA also served to intimidate political opponents; it was also included in mobilization plans by the Bavarian government . The military training was carried out by the 7th (Bavarian) Division of the Reichswehr (in particular by the 7th Engineer Battalion and the 19th Infantry Regiment ).

The Munich SA comprised around 1150 men in 1923 and had artillery hundreds and cavalry platoons. Their commanders took on military terms such as rifle or gun leader. The year 1923 was marked by strong polarization between right and left groups ( German October ). At Röhm's instigation, the "Working Group of Patriotic Associations" was set up in February 1923. In it the SA, the "United Patriotic Associations of Munich", the "Reichsflagge", the "Bund Oberland" and the Gau Niederbayern of the federal "Bavaria and Reich" came together. On May 1, 1923, the working group tried to prevent the SPD and trade unions from moving in Munich in May and pulled several thousand armed men, including 1,300 members of the SA, together on the Oberwiesenfeld. But she bowed to the counter-march of the police and the Reichswehr without a fight and returned the weapons that she had obtained from army depots against the prohibition of the Reichswehr. Röhm, whom the Bavarian Reichswehr leadership under Otto von Lossow held responsible for this, was removed from his previous post in the Reichswehr and, after a vacation, was transferred from Munich to Grafenwohr.

On November 9, 1923, the roughly 2,000 members of the SA took part in the Hitler-Ludendorff putsch under their military leader Hermann Göring . This coup attempt 16 NSDAP members (including five were raiding party men's) from the Bavarian police and the military shot; the party thus had its first “ martyrs ”. Goering fled to Innsbruck.

Period of prohibition 1923–1925

After the putsch, President Friedrich Ebert transferred executive power to the head of the Reichswehr - Hans von Seeckt . On November 23, the latter issued a ban on the NSDAP and the KPD. In order to circumvent this ban, the SA was designated as a frontbann from April 1924 to February 1925 .

Ernst Röhm, who had been entrusted by Hitler with the military leadership of the forbidden Kampfbund and the now banned SA, sat after his release from prison (April 1, 1924) at a meeting held in Salzburg on May 17 and 18, 1924 as an SA- Führer instead of Goering.

Röhm developed guidelines for a reorganization of the SA. As early as 1924 outside of Bavaria under cover names or as part of other associations, the first SA groups in the Ruhr area and Westphalia and also some in northern, eastern and central Germany were formed, although the fluctuation of members within the spectrum of the military associations was very high.

In addition, Röhm drafted plans for a defense movement throughout the Reich, independent of the party, called "Frontbann". The SA, which was still banned, was supposed to form the core of the movement, but it was also open to other military organizations. Although Hitler rejected this plan, fearing that such activities could endanger his release and the SA could be withdrawn from him, Röhm succeeded in establishing the "Frontbann" in August 1924. This soon had around 30,000 followers.

Restructuring 1925 to 1930

After the re-establishment of the party, which took place on February 27, 1925, because Hitler had been released prematurely from prison at the end of 1924, the SA was reorganized under Ernst Röhm just one day after its ban was lifted on February 26 and in the course of the Reorganization of the NSDAP in line with its regulations of February 1923. After the reorganization of the SA by Röhm, which was de facto unauthorized, he asked Hitler on April 30 whether the SA could see itself again as the party's "military association" and received a written refusal four weeks later from the Fuehrer's office: According to the letter, Hitler only needs a hall protection. According to Hitler, the resurrected SA should primarily be an auxiliary force of the party - and not a military association as part of a comprehensive National Socialist defense movement. Thereupon Röhm resigned bitterly and disappointed all leadership positions in the front line and the SA. Until the completion of the reorganization of the party, the SA remained leaderless and was assigned to regional party leaders as their "auxiliary force".

On November 1, 1926, the former Freikorpsführer Franz Pfeffer von Salomon took over the SA leadership as Supreme SA Leader (OSAF), to which all of the NS combat units (SA, SS, HJ and NS Student Union) that had existed until then were subordinated.

The main tasks of the SA were now, according to Hitler's will, marches and "civil" violent attacks against political opponents. This included primarily members of the KPD and the SPD ; the SA fought street and hall battles with the communist Red Front Fighter League and the social-democratic republican black-red-gold banner . It also attacked Jews and Christian groups such as the Kolping Youth .

At the beginning of December 1926, a uniform, hierarchical organizational concept was created, the basic unit of which was the group with around a dozen SA men. Several groups resulted in a troop, up to five troops a storm. Up to five storms were combined into one standard, several standards under the direction of a gaus tower. In mid-1927, the brigade joined the organization between Standarte and Gausturm. By autumn 1927, the SA had 17 Gaustürme in the Reich. Since 1928 they have been subordinate to the seven Oberführer Ost, Nord, West, Mitte, Süd, Ruhr and Austria in their area. SA Oberführer Süd in Munich was the former Major August Schneidhuber. The total strength of the SA for 1926 is estimated at 10,000-15,000 men. In Bavaria there were the Gaustürme Upper Bavaria-Swabia and Franconia; the Palatinate and Saarland together also formed a Gausturm.

In 1926 and 1927, the Munich party leadership aimed at winning over the workforce and was therefore radically anti-capitalist. At the same time, however, the SA acted aggressively against the left-wing parties. The constant tendencies towards radicalization in the SA resulted in constant tension with the party leadership.

In May 1927, the Munich SA rebelled against what they considered to be too moderate and bureaucratic party leadership. One of the leaders was the businessman and former lieutenant Edmund Heines, who had been incorporated into the SA on September 2, 1926 with the remnants of the Roßbach Freikorps. The crisis was finally resolved only in the following year. Heines was excluded, but rehabilitated again in 1929. In Central Franconia, the SA practically disintegrated in 1928 after a conflict with Gauleiter Julius Streicher. It was then reorganized under Streicher by the new Gausturmführer Philipp Wurzbacher.

In 1929 the OSAF deputy areas East, North, West, Middle, South, Ruhr and Austria took the place of the Oberführer. The southern area comprised Bavaria with the two Gaustürme Bavaria and Franconia as well as the Gaustürme Baden and Württemberg. The Gausturm Pfalz / Saar belonged to the West area. OSAF deputy south was the previous Oberführer Süd, August Schneidhuber. The SA brigade "Greater Munich" was divided into standards I and II in March 1929. In August a third Munich-Land standard was added. Since March 1929, the over 40-year-old SA men were grouped in reserve storms in order to increase the effectiveness of the active storms.

1930 until the NSDAP came to power

In the run-up to the Reichstag elections in 1930 , there was a serious crisis between the SA and the party leadership. The SA demanded that leading members be guaranteed a promising place on the list, which Hitler refused. SA leadership and mandate must remain strictly separate. When Pfeffer von Salomon adopted this principle, the Berlin SA went on strike: On August 30, OSAF-Ost Walther Stennes let the Berliner SA stand for a general roll call instead of guarding the hall for an election campaign with Joseph , as planned Goebbels in the Berlin Sports Palace . One day later, his SA men occupied the NSDAP's Gau office and the editorial offices of the newspaper Der attack . This resulted in fights that were only ended by the police called by the SS. Hitler then hurried from Munich to Berlin and restored calm by taking over the post of OSAF himself from Pfeffer von Salomon, who had recently resigned. The post of Chief of Staff, which Ernst Röhm took over, was newly established for day-to-day work.

Stennes did not give up in the following years. Unlike Hitler, who relied on legality since the Ulm Reichswehr trial, OSAF East wanted to conquer power in Germany by force, with a revolution . This course put the NSDAP in danger when the Brüning government issued an emergency ordinance in March 1931 , which allowed it to override certain basic rights of the Weimar Reich constitution . Hitler then deposed Stennes, who in turn triggered the so-called Stennes Putsch : On April 1, 1931, his SA men forcibly occupied the premises of the Berlin Gauleitung and the attack and issued their own number. In it, Stennes committed himself to revolution and socialism . However, he did not succeed in pulling larger parts of the SA over to him. After the Berlin police ended the occupation, Stennes and around 500 SA men were expelled from the NSDAP.

During this time, the SA had become a powerful and well-structured organization. The growth of the SA was favored by the global economic crisis and the electoral successes of the NSDAP. In November 1930 the SA had 60,000 members; in August 1932 there were already 471,384 members. When he took office in January 1931, Röhm had found an SA with almost 77,000 men. By April 1931 it had grown to 118,982 men, and in November 1931 it had passed the 200,000 man mark. In December 1931, 260,438 men marched under the flags of the SA. In the summer of 1932 there were 445,279 men. At the turn of the year 1932/1933 the SA numbered 700,000 men and at the end of 1933 there were around 2.9 million SA men. The strong growth also resulted from an extreme fluctuation of street fighters alternating with the KPD and the Red Front Fighters League and a strong influx of party members of the NSDAP after the ban on membership on May 1, 1933.

A ban on the SA issued by Chancellor Heinrich Brüning on April 13, 1932 because of the terrorist wave lifted - after interventions by SA leader August Wilhelms von Prussia , fourth son of Kaiser Wilhelm II, on April 14, 1932 with the then Reich Defense Minister and Interior Minister General Groener , and the NSDAP leader Adolf Hitler on June 13, 1932 with Reich Chancellor von Papen (then Reichswehr Minister: General von Schleicher) - Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen (Brüning's successor from June 1, 1932) on June 14. In the run-up to the Reichstag elections on July 31, 1932 , there were civil war-like conditions with a total of around 300 dead and over 1,100 injured, in which the SA was significantly involved. The struggle for new seats in the Reichstag in the summer of 1932 unleashed criminal energies in the SA, which rioted unrestrainedly against political opponents; In the last ten days of the election campaign, 24 people were killed and 284 seriously injured in Prussia alone.

Role of the SA in the takeover of power by the NSDAP

The SA, which has now grown to more than 400,000 members, celebrated Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933 with a night torchlight procession coming from the Großer Stern in Berlin through the Brandenburg Gate to the Reich Chancellery on Wilhelmstrasse .

Many SA men expected the immediate seizure of power in the style of a violent coup. The Boxheim documents with plans for a coup d'état by the SA had already been made public in autumn 1931 .

But the leadership of the National Socialists shied away from the option of a violent coup by the SA, which at that time would have meant a civil war against the Red Front Fighter League and the Reich Banner with an unclear outcome. It was also not certain whether the Reichswehr and above all the Prussian police, which had been under strong social democratic influence during the Weimar Republic, would unanimously obey the instructions of the new government. The political goal of the Nazi leadership was not to overthrow, but to bring about conformity .

The SA remained active. Immediately after January 30, 1933, several people fell victim to the SA in Berlin alone and many were injured. SA troops organized house searches and arrests on their own.

On February 22, 1933, the provisional Prussian interior minister Hermann Göring founded the auxiliary police . It was mainly recruited from the ranks of the SA, which was thus integrated into the state power apparatus. The SA could now operate with state authority and extensive competencies, which on the one hand satisfied its need for action, on the other hand also channeled it. In addition, the massive presence of the SA caused the regular police force to adapt to the new rulers. It is estimated that around 3,000 to 5,000 SA men were appointed auxiliary police in Berlin alone.

In this context, the SA field police , the core of the later SA Feldjägerkorps, with headquarters in the Berlin SA prison Papestrasse , appeared. While this special unit of the SA leadership was initially used to persecute and detain opponents of the regime, it was later increasingly given internal organizational tasks of order, which it carried out under its new name SA Feldjägerkorps until 1935. The Prussian auxiliary police, however, were disbanded at the beginning of August 1933.

The “ Reichstag Fire Ordinance ” was issued immediately after the Reichstag fire on the night of February 28, 1933, a few days before the 1933 Reichstag election . Thus the basic rights of the Weimar Constitution were practically overridden and the persecution of political opponents of the NSDAP by the police and the SA legalized, which had started on a large scale immediately after the seizure of power.

The Navy SA tortured political opponents on the “ Ghost Ship ” in Bremerhaven from May to October 1933. Between March and autumn 1933, the SA took unrestrained revenge on political opponents and ideological enemies. Estimates speak of around 50,000 prisoners in their own, sometimes "wild" concentration camps.

For Hitler, precisely because of the terror it wielded, the SA was extremely useful in the first phase of the seizure of power. On the one hand, with their help, he was able to intimidate and terrorize his opponents, on the other hand, he was able to present himself to the conservatives as the only person who was able to tame the SA. Depending on the circumstances, he implicitly threatened to give the SA a real free hand or promised to act moderately on them. With this tactic he got many conservatives to agree to the terrorism and to reward him for keeping the terror within "tolerable limits". The SA leaders who had gained power and influence in this way and who had taken on the role of a local commissioner had to be “taken care of” after the end of the terror era. For example, the sporting inexperienced commissioner Hans von Tschammer und Osten was resigned to the new post of sports commissioner , and shortly after the seizure of power he was appointed Reich Sports Commissioner or Reich Sports Leader with the rank of State Secretary .

"Röhm Putsch" 1934

After Adolf Hitler had increasingly secured his power in the course of 1933, also thanks to the SA, he withdrew his favor in the summer of 1934. Ernst Röhm , who was appointed chief of the SA staff in 1930, pursued a conception deviating from Hitler's regarding the role of the SA combat organization, which he again wanted to remove from the control of the party. After the “seizure of power”, he called for a “second revolution” and the creation of a “National Socialist People's Army” to replace the Reichswehr. Their units should join the SA, merge into it and thus form the "National Socialist Army".

For Hitler, the SA had fulfilled its terrorist function in order to achieve power. In the summer of 1934, the large organization was more of an obstacle to the development of power. Hitler, who at that time needed the support of the Reichswehr for his future war plans, let Röhm's deliberately falsified and widespread quotations spread the impression that Röhm wanted to instigate an uprising. Given the 3.5 million SA members, the authorities (police and / or Reichswehr) would have faced a difficult task. Röhm emphasized several times internally in party circles: "Remember, almost four million bullies are behind me!" Even if this was apparently said jokingly, it sounded extremely threatening to Hitler and the Reichswehr leadership. These "revolutionary rumors" were spread mainly by the former SA leader Hermann Göring and the Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler , who nevertheless repeatedly assured Röhm in writing of his unconditional loyalty to himself and the SS. To date there is no evidence that a putsch by Röhm was seriously planned or was imminent.

On June 30, 1934, Hitler visited Röhm at his vacation spot in Bad Wiessee . He accused him of plotting coups and blamed him for his homosexuality . In the party leadership it was an open secret that Röhm and parts of his environment had homosexual tendencies . Newspapers had disseminated this information even before 1933, such as Fritz Gerlich's “ Der direkt Weg ”. Hitler's feigned horror at Röhm's homosexuality, which was officially announced after the “Röhm Putsch”, was commented on by a political joke : "How horrified will Hitler be when he realizes that Goering is fat and Goebbels has a clubfoot?"

On June 30th and July 1st, 1934, the SA leadership was arrested by members of the notorious SS-Sturmbannes "Oberbayern" in the early hours of the morning and shot a little later by a firing squad specially set up for the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler under Josef Dietrich .

Röhm himself was shot on July 1st in his prison cell by the Dachau commander of the guard guard "Upper Bavaria" Theodor Eicke and his deputy Michel Lippert . As part of the Röhm putsch, other uncomfortable people were arrested and later murdered, including the SA-Obergruppenführer Heines, the former Reich Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher with his wife, the former NSDAP organization leader Gregor Strasser , the former Bavarian State Commissioner General Gustav von Kahr and Herbert von Bose and Edgar Julius Jung , both close collaborators of Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen .

The liquidation had several advantages for Hitler:

- By eliminating paramilitary competition, Hitler gained the trust of the Reichswehr generals.

- The threat potential of the SA was eliminated for the further development of power.

- With the disempowerment of the SA, consisting primarily of the unemployed and petty bourgeoisie, Hitler rose in favor of large and heavy German industry.

- By eliminating the leadership of the SA, which had grown to 4.5 million members by June 1934, a potentially dangerous internal party power was neutralized

- The disarmament of the SA, with the handing over of weapons to the Reichswehr, advanced the rearmament of the Reichswehr.

The neutralization of the SA made it possible for the leader of the SS , Heinrich Himmler, to emancipate the SS , originally conceived as Hitler's bodyguard, from the parent organization SA and to establish it formally as an independent organization under National Socialism. In the years that followed, Himmler was able to develop the SS, its subdivisions (e.g. SD , Waffen-SS ) and thus also himself an almost unprecedented level of power in the Nazi state.

Role of the SA after 1934

After Röhm and his followers were eliminated - the estimates range from 150 to 200 deaths, including 50 leaders - the SA became almost insignificant and was mainly concerned with giving its own members pre-military training. Officially, the SA downgraded its training to "sport with military relevance".

The number of members showed an enormous shrinkage of the SA: They fell from 4.5 million (June 1934) to 2.6 million (September 1934), to 1.6 million (October 1935), to 1.2 million in 1938. At the beginning of 1940 the SA only had around 900,000 members. The new chief of staff Viktor Lutze created an SS-like elite standard within the SA. This was called SA-Standarte Feldherrnhalle , was a standing and armed unit and was considered the SA counterpart to the units of the SS available troops . Numerous SA departments were disbanded and assigned to other associations.

The SA was deployed nationwide again on the “ Reichspogromnacht ” against the Jewish population in November 1938 and once again showed its terrorist energy.

When the war broke out in 1939, the SA took over the training of postponed conscripts in "SA Wehrmannschaften", which in April 1940 made up 1.5 million volunteers. At the beginning of the war, 60% of the ranks and 80% of the leaders were drafted into the Wehrmacht. In Danzig and the Sudetenland, SA Freikorps were temporarily formed, but they were also absorbed into the Wehrmacht, as service in the SA did not exempt them from compulsory military service.

During the Second World War , SA men, unless they had been drafted into the Wehrmacht , were used to look after the troops and for pre-military training. The rest of the SA performed auxiliary services for the armed forces, police, customs, air protection, SS, border guards and other organizations during the war. Around 80,000 armed SA men were subordinate to the Gauleiter in "storms for special use" as police reinforcements against possible uprisings by the population.

Shortly before the end of the war, the SA was also used as a reservoir for Volkssturm fighters , with SA members often committing acts of violence against prisoners of war or those willing to surrender.

After Lutze's death in 1943, Wilhelm Schepmann took over the management until the end of the war.

About several SA generals who had already held leading positions in the police apparatus of the Third Reich and were sent by the regime as envoys to the south-eastern European vassal states - which was only declared as a temporary diplomatic service for the sake of external appearance, in fact they were more likely to be designated German Reich Commissioners of the areas to be occupied - the SA was also more and more directly involved in the deportations of Jews there and the Holocaust than had long been assumed.

Judgment on the SA in the Nuremberg trials

With the Control Council Act No. 2 of October 10, 1945, the SA was banned by the victorious powers. In contrast to the SS, which in the meantime had significantly more members and was spun off from it in 1934, and despite its murders and crimes, the SA was not classified as a “ criminal organization ” in the Nuremberg trials - against the vote of the Soviet Union - because its members 1939 "in general" were not involved in criminal acts.

Motto

The SA's motto was “Everything for Germany”.

Hierarchical structure

guide

Until 1926, the SA commandant was referred to as the "Supreme SA Leader" (OSAF) . Until then, the SA was regarded as a National Socialist fighting organization that was independent of the NSDAP . From autumn 1926 Adolf Hitler took over the leadership of the SA, that is to say, himself became Supreme SA Leader. The new title SA Reichsführer was introduced for the previous incumbent ; from then on this was under the control of the party. With the creation of the SA Reichsführer, the counterpart for the supreme commandant of the SS was created ; this, from 1925 onwards, also had the rank of Reichsführer , but was formally still subordinate to the SA Reichsführer.

When Ernst Röhm returned to the SA, the rank of Chief of the SA Staff ( SA Chief of Staff for short ) was introduced. The best known holder of this rank was Ernst Röhm. After Röhm's murder in the Röhm Putsch , Viktor Lutze became chief of staff and on August 23, 1934 he was personally subordinate to Hitler as " Reichsleiter SA ". He now received his own rank badge. After Lutze's death in a car accident in May 1943, Wilhelm Schepmann became Chief of Staff.

Organization of the construction

The SA was set up and coordinated in accordance with the “Basic Orders” (GRUSA) and “SA Orders” (SABE) of the Supreme SA Leader (OSAF).

Internal structure (as of January 30, 1933)

SA man was the generic designation for all members of the SA and included SA leader and team ranks. All applicants who were not yet placed in the group were designated SA candidates. SA reserves I and II were formed after the takeover of power (1933) from the former soldiers' associations " Kyffhäuserbund " and " Stahlhelm ". Until March 1931, the “Gaustürme” were the highest administrative authorities. From May 1, 1931, these were reorganized into ten groups and two subgroups; by 1932 there were 14 SA groups. By July 1933, the SA was combined into eight main groups, which consisted of 21 SA groups. The highest administrative institution was now the “Leadership Main Office SA” with four “SA inspections ” (West, Southeast, Central, East). In May 1934, three more main groups were added. After the " Röhm Putsch " the SA was reorganized until August 1934. The main groups, the inspections and various departments of the SA Leadership Main Office were dissolved, and some sub-groups such as the SS became independent.

Organizational structure of the SA from August 1934

- Structure of the SA

| usual division | resulting theoretical total strength |

annotation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supreme SA leadership | |||

| SA group | 2–6 brigades | 3,888-777,600 men | were formed according to the population density and other "SA service conditions" |

| brigade | 3-9 standards | 1,944-129,600 men | |

| Standard | 3–6 storm wards | 648-14,400 men | |

| Stormbane | 3–10 storms | 216-2,400 men | |

| Storm | 3 squads | 72-240 men | |

| Squad | 3–5 furrows | 24-80 men | |

| Crowd | 1-2 rotten | 8–16 men | |

| Rotte | 4–8 men | 4–8 men | |

In 1938 the SA was reorganized based on the military model. From June 1938 this structure was adopted for the "SA Obergruppe Ostmark", which was incorporated in March of the same year. The SA as a whole was structured as follows on January 30, 1939:

1. General SA

- 1.1 Active SA-I (between 18 and 35 years of age)

- 1.2 Active SA-II (between 35 and 45 years of age)

2. SA reserve (over 45 years of age)

3. SA military teams

These were subdivided according to military specialist areas and areas of activity and weapon colors were now also introduced for the SA , which in turn replaced the colors of the SA groups:

- News-SA (lemon yellow)

- Reiter-SA (orange)

- Pioneer SA (Black)

- SA hunters / SA rifle units (green)

- Medical SA (royal blue)

- Navy SA (navy blue)

- SA foot standards (gray)

- SA group rods (light red)

- Supreme SA leadership (carmine)

Two former SA units were removed after Hitler came to power and built into independent formations with other organizations:

- The Motor-SA was reorganized with other automobile associations to the NSKK .

- The Flieger-SA was incorporated into the NSFK together with the Flieger-SS .

Uniforms and symbols

Uniformity

Initially (1920-1923) the former soldiers of World War I in the SA wore their military uniform. Members who were not previously soldiers put on gray windbreakers to replace uniforms. They could only be recognized by their red armbands with a swastika.

The party shirt, later officially known as the “brown shirt”, was introduced by chance: The Freikorps and SA leader Gerhard Roßbach , who fled to Austria at the end of 1923, was able to acquire a larger post of brown shirts, originally for the German protection force in Africa under Lettow-Vorbeck were intended. After his return, Rossbach introduced these shirts to the SA, which were worn as the "Lettow shirt" from 1924.

The "earthy" brown was declared the color of the right-wing movement from 1925 and later interpreted as an expression of a special bond with home and soil. It was chosen by chance because of the purchase of the "Lettow shirts", inspired by free corps uniforms and in contrast to the red of the communists and the black of the Italian fascists.

In an oral conversation with Georg Franz-Willing , who emerged as an employee of the Institute for Historical Review and a Holocaust denier , Roßbach said, however, that he had a decisive influence on the appearance of the brown shirt. In the so-called “Book of Honor of the SA” from 1934 it is also described that the brown shirt was originally worn by the “Roßbach departments” of the SA and was first used on April 5, 1925. It is therefore quite conceivable that Roßbach merely wanted to distance himself from the Nazi regime with his original statement of a "chance discovery". The uniform had to be purchased by every SA man himself, which is why you can often see incompletely equipped SA members in (especially early) pictures.

The “ armband ”, a red ribbon with a black swastika in a white circle, was worn on the left arm .

The SA men were well aware of the propaganda effect of the brown shirts in public. When the public wearing of brown shirts was forbidden in Bavaria and Prussia in 1930, the SA leadership evaded wearing white shirts in a lightning action, without otherwise being disturbed in their activities, which attracted the public's attention SA only further strengthened. After the ban had expired, people returned to wearing the brown shirt.

In 1932 Hugo Boss was commissioned by the NSDAP party leadership to produce standardized uniforms for the NS organizations. The occasional claim that Hugo Boss was responsible for designing the uniforms of the Nazi organizations is false. They were responsible for this themselves. With the exception of the SS , uniforms in various shades of brown were introduced in all party organizations.

The SA men wore a brown tie , brown breeches and boots with their brown shirt (in rare cases and mainly by senior leaders on festive occasions, they also wore “normal long trousers” and a uniform jacket in a military style, also with a brown base color). Typical was the SA cap, a shaft cap with a brown base color, originally soft and monochrome brown with a leather peak and storm strap. From August 1929, the SA cap was given a stiff body, from the upper colored trimmings the territorial affiliation of the SA man (Gau and territorial division) was recognizable. Silver strands of various widths also indicated the service position of the wearer.

The badges of rank were worn on the left, from the Standartenführer upwards, on both collar tabs, the basic color of which matched the colored edging of the SA cap. A silver, twisted cord ( piping ) ran around the collar of the brown shirt at these ranks . The numbers on the right-hand mirror denote the SA storm and the standard, for example: 1/5 means storm 1 of the standard 5. The members of the staff only had the number of the standard, for example 5 or the Sturmbann, for example III / 5. On the right shoulder pieces of armpit were worn in two-tone cord, silver and gold. If the SA man was also a member of the NSDAP (which was not a matter of course, but was a prerequisite for senior SA leaders for their service position), the party badge or a pin in the shape of the party eagle was initially placed on the brown binder at the level of the breast pocket buttons worn by the NSDAP. Later it became customary to wear the party badge on the left breast pocket.

The uniform also included a brown leather belt on which the SA dagger was worn on the left hip, with a belt lock and a shoulder strap.

Flag cult

From the beginning, the use of flags, mainly with the symbol of the swastika, played an important role in the SA as a standard , but also in mere accumulation as decoration vis-à-vis the public.

In addition to so-called “storm flags”, which were handed over to the respective “storm departments”, each unit carried an “SA standard” - designed by Adolf Hitler in 1922 - as a standard, whose design was based on old Roman models and models from Napoleon Time leaned and which was the subject of an extensive flag cult. The standards had the advantage over the "storm flags" that their image was always visible regardless of the weather conditions. The inscription "DEUTSCHLAND ERWACHE" came from the song "Sturm, Sturm, Sturm" by Dietrich Eckart . The first four standards were made by the Munich goldsmith Gar and ceremoniously handed over in January 1923 at the party congress in Nuremberg. The extensive introduction of the SA standards began in Weimar in 1926, when Adolf Hitler presented the SA standards "with a promise of loyalty" and a mystical ceremony bordering on religious matters.

At the 1927 party congress in Nuremberg, another 12 SA standards were "ceremoniously consecrated" before they were handed over to the carrier units. For this purpose the swastika flag was used, which had been carried as a flag during the Hitler putsch on November 9, 1923 in Munich during the march on the Feldherrnhalle. The flag was declared a " blood flag " to demonstrate its association with the movement's first " martyrs ". Whether the flag was actually "soaked" on this occasion with the blood of wounded or shot demonstrators is controversial. With a corner of this "blood flag" Hitler touched the flag of every new standard in the course of the flag consecration in blood-and-soil symbolism , about "the forces of the martyrs of the movement" on the flag and thus also on the SA unit led by it transferred to.

Veteran SA men

Members of the SA who had joined in the period from January 1, 1925 up to and including January 30, 1933 were referred to as "veteran SA men". From February 1934 they wore the so-called " Ehrenwinkel der Alten Kampf " on their left upper arm . But already in October of the same year the angle was replaced by the system of the gray-silver "honor strips". These were worn on the cuffs of both lower sleeves, their number and width differed according to the year of entry.

From the 1930s onwards, graduates of the SA Reichsfuhrer School were awarded the Tyr rune .

SA sport badge / SA military badge

The SA sports badge was created in order to create a closer connection to National Socialist ideas among the ranks of "non-political" athletes. It was renewed by Hitler on February 15, 1935, so that non-members could also purchase it. From January 19, 1939, it was renamed SA-Wehrabzeichen.

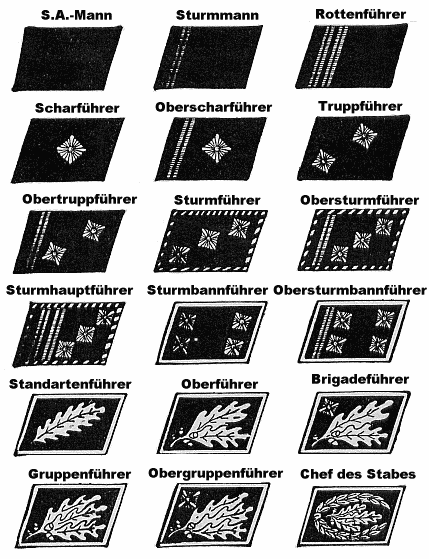

Ranks

The structure, badges and ranks of the SA served as a model for the "NSDAP branches" SS , NSKK and NSFK that emerged from the SA .

The ranks of service ( see NS ranks with a tabular comparison of SA, SS, police and armed forces ) were:

- Teams

- SA candidate

- SA man ( soldier of the Wehrmacht)

- SA-Sturmmann (Ober ... e.g. Oberschützen)

- SA-Obersturmmann, not in the picture on the right ( private )

- SA Rottenführer ( Obergefreiter )

- Unterführer

- SA-Scharführer ( NCO )

- SA-Oberscharführer ( Unterfeldwebel )

- SA troop leader ( sergeant )

- SA Obertruppführer ( Oberfeldwebel )

- SA main troop leader (not in the picture on the right)

- Officers

- SA-Sturmführer ( Lieutenant )

- SA-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant )

- SA-Sturmhauptführer ( Captain )

- from 1939/40 SA Hauptsturmführer

- SA-Sturmbannführer ( Major )

- SA-Obersturmbannführer ( Lieutenant Colonel )

- SA Standard Leader ( Colonel )

- SA Oberführer (no equivalent)

- General ranks

- SA Brigade Leader ( Major General )

- SA group leader ( lieutenant general )

- SA-Obergruppenführer ( General (with the addition of the type of weapon) )

- Chief of Staff of the SA

Press organ

Since March 1928 a monthly supplement appeared in the Völkischer Beobachter under the title “Der SA-Mann”, which was published as an independent weekly paper by the SA leadership from January 5, 1932. The chief editor of the newspaper, which dealt primarily with military issues as well as internal affairs of the SA and NSDAP, was Joseph Berchtold .

Financing the SA

In 1929 the SA had its own witness shop in Munich, which apparently worked profitably and developed into a coordination point for all relevant institutions in the Reich. Since August 1930 it has been under the Reich Treasurer of the NSDAP.

At the beginning of 1930, the compulsory insurance of the members, which had been mandatory since 1926, developed into the basis for a separate party company. Although a large number of the members refused to join, the company generated surpluses.

From the 1930s onwards, the major events held by the SA contributed to the financing in Munich to a considerable extent. Since July 1930, the local groups had to forward 50% of the income and collections via the Gau leadership to the respective SA Gau leadership, which had to bear all propaganda costs in the Gau. This improved the financial situation, but the SA did not finally get out of its financing problems. Much of the cost, e.g. B. for uniforms and for propaganda trips, the SA men denied out of their own pockets.

Equipment and service costs, as well as contributions for obligatory party membership in the NSDAP, had to be borne by the SA men themselves. Under the leadership of Pfeffer, grants and social benefits could be awarded since 1929, so that the mass unemployment of the world economic crisis could be used as a mass influx.

Social structure of the SA

The characterization of the SA as “rule of the mob” is not wrong either, but falls short and served apologetic purposes. For example that of saving the honor of the German bourgeoisie: as if political rule had been torn from “the street” by a (ragged) proletarian gang in the form of the brown shirts of the SA in 1933.

Very early on, significant parts of the SA members were not workers and unemployed, but students and middle-class members, not to mention the massive support that the SA found among Protestant pastors.

The higher leaders from the Standartenführer upwards were almost exclusively participants in the First World War. They had served in the Imperial Army and when the war was lost, most of them were left with nothing professional or business. Former career officers and free corps leaders dominated the highest ranking. The SA elite was shaped by the professional ethos of the Prussian-German officer and was characterized by a pronounced sense of class. All Obergruppenführer were former World War II officers, in Bavaria about Hans Georg Hofmann, Kraußer and Schneidhuber. The same applied to the group leaders like Friedrich Karl Freiherr von Eberstein and Wilhelm Stegmann. This privileged group of higher SA leaders demarcated itself from the mass of economically oppressed SA people, whose opportunities for advancement were slim. The SA leadership became increasingly alienated from the grassroots. The SA was not attractive to the Bavarian farmers. In April 1932 they made up only 7.3% of the members. Both the proportion of workers and the unemployed were in all probability greater in the SA than in the party.

In contrast to the SA leadership, the lower and middle ranks were mostly younger people born between 1900 and 1910. Historians Siemens classifies them as the “war youth generation”, which was marked by a childhood and youth for mobilization and during the First World War.

Training in the SA

The most important components of the SA training were marching and drills, sport and field exercises and the mostly weekly troop or storm evenings.

In March 1931, plans were drawn up for a Reichsführer-school of the NSDAP. On March 31st, 1931 the Prussian major a. D. and SA group leader Kurt Kühme was appointed. The Reichsfuhrer School opened on June 15, 1931 in Munich. It was primarily dedicated to training SA leadership personnel. The first lectures were given by Hitler (on political tasks) and Himmler (on the principle of the National Socialist selection of leaders). Other leading National Socialists also acted as speakers. The practical training included the handling of SA tasks, formal SA service and sport with daily basic physical training, team competitions, hikes and field exercises. However, the focus of the training was in the area of propaganda. In the first courses in 1931, 468 SA leaders were trained.

The Reichswehr saw the SA as an important reservoir for the next generation of military personnel. Its members were able to take part in pre-military training via the Reich Board of Trustees for Youth Enhancement. In Bavaria, courses were held at the military training areas in Lechfeld and Hammelburg.

See also

- Black Reichswehr

- Horst-Wessel-Lied , the battle song of the SA

- Storm song

- List of SA-Obergruppenführer

- List of SA group leaders

- List of SA brigade leaders

literature

- Bruce Campbell (historian) : The SA Generals and the Rise of Nazism. Univ. Press of Kentucky, Lexington 1998, ISBN 0-8131-2047-0 .

- Peter Longerich : The brown battalions. History of the SA. Beck, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-406-33624-8 . (New edition: History of SA.Beck , Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49482-X ).

- Yves Müller, Reiner Zilkenat (Ed.): Civil War Army . Research on the National Socialist Sturmabteilung (SA). Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-631-63130-0 .

- Sven Reichardt : Fascist combat alliances. Violence and community in Italian squadrism and in the German SA. Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2002, ISBN 3-412-13101-6 .

- Daniel Siemens : Sturmabteilung - The history of the SA, Siedler, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3827500519 .

Web links

- Literature on the SA in the catalog of the German National Library

- LeMO : The Sturmabteilung (SA)

- The future needs memories : the Sturmabteilung (SA) in the Third Reich

- Martin Schuster: The SA in the National Socialist "seizure of power" in Berlin and Brandenburg 1926–1934 , dissertation at the Technical University of Berlin, 2005 (PDF; 3.8 MB).

- SA field police memorial site SA prison Papestrasse

- Bernhard Sauer: Goebbels »Rabauken«. On the history of the SA in Berlin-Brandenburg. (PDF; 6.5 MB) In: Yearbook of the Berlin State Archives , 2006.

- Verfassungsschutz.de: Right-wing extremism: Symbols, signs and prohibited organizations (PDF) ( Memento from January 16, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Painted signs and symbols of the state as well as the NSDAP and their structures (= shape and color . No. 12 ). Berlin 1936 (special edition).

- ↑ SA badge . In: Robert Ley (ed.): Organization book of the NSDAP . 7th edition. Central publishing house of the NSDAP, Franz Eher Nachf., Munich 1943, badge of the NSDAP. (Fig.).

- ^ A b c d Daniel Siemens and Rudolf Walther: Militant masculinity. In: https://taz.de/ . taz, July 31, 2019, accessed December 3, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Wolfgang Petter: Sturmabteilung (SA) . In: Christian Zentner and Friedemann needy (ed.): The great lexicon of the third realm . Südwest Verlag, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-517-00834-6 , pp. 569 f .

- ↑ Peter Longerich: The brown battalions , p. 22 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Paul Hoser: Sturmabteilung (SA), 1921-1923 / 1925-1945. In: https://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/ . Retrieved December 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Björn Müller: " Storm Troops: The Emperor's" Special Forces " " from March 29, 2017 on FAZ-Net

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: The Order under the Skull - The History of the SS. Weltbild-Verlag, Augsburg 1992, ISBN 3-89350-549-0 , p. 22.

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: The Order under the Skull - The History of the SS. Weltbild-Verlag 1992, p. 23

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: The Order under the Skull - The History of the SS. Weltbild-Verlag, 1992, p. 6

- ↑ Peter Longerich: The brown battalions , p. 48

- ↑ a b Heinz Höhne: The Order under the Skull - The History of the SS. Weltbild-Verlag, 1992, p. 27

- ↑ Peter Longerich: The brown battalions , p. 52

- ↑ Peter Longerich: The brown battalions , p. 53

- ↑ a b Peter Longerich : The brown battalions. History of the SA . C. H. Beck, Munich 1989, p. 102 ff

- ^ Ralf Georg Reuth : Joseph Goebbels. The diaries. Vol. 2: 1930-1934. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1992, p. 575, note 25.

- ^ Ordinance of the Reich President to combat political excesses. From March 28, 1931. on documentarchiv.de, accessed on December 20, 2013.

- ↑ See Table 4 in: Michael Grüttner , Das Third Reich. 1933–1939 (= Handbook of German History , Volume 19), Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2014, p. 125

- ^ A b Heinz Höhne: Mordsache Röhm. In: https://www.spiegel.de/ . Der Spiegel, June 11, 1984, accessed December 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Ernst Deuerlein (ed.): The rise of the NSDAP in eyewitness reports . Edited and introduced by Ernst Deuerlein. 5th edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-423-02701-0 , p. 383-384 .

- ↑ "In the year after the seizure of power, the number of members of the SA increases tenfold to over 4 million." (Kerstin Arnold, Auf: Future needs memory )

- ↑ Arnd Krüger : "Today is Germany and tomorrow ..."? The struggle for the sense of conformity in sport in the first half of 1933. In: W. Buss, A. Krüger (Ed.): Sportgeschichte. Maintaining tradition and changing values. Festschrift for the 75th birthday of Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Henze (= series of publications by the Lower Saxony Institute for Sports History. Volume 2). Mecke, Duderstadt 1985, pp. 175-196.

- ↑ Peter Longerich: The brown battalions. History of the SA. CH Beck, Munich 1989, p. 184.

- ↑ see also: Eugen Kogon : Der SS-Staat .

- ↑ See Table 4 in: Michael Grüttner , Das Third Reich. 1933–1939 (= Handbook of German History , Volume 19), Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2014, p. 125.

- ^ Kurt Schilde: Sturmabteilung . In: Wolfgang Benz , Hermann Graml and Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 753 f.

- ^ Daniel Siemens : Sturmabteilung. The history of the SA. Siedler, Munich 2019, p. 375 ff.

- ^ The Trial of the Major War Criminals in the International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg November 14, 1945 to October 1, 1946 (1947), Volume 22, p. 591.

- ↑ Right to extreme in the Bundestag. Time online from October 24, 2017

- ↑ a b c d e Organization book of the NSDAP, 1937 (3rd edition), "Structure of the SA.", P. 364 ff.

- ↑ a b David Littlejohn: The SA 1921-45 , p. 7

- ^ Daniel Siemens: For the SA people, the SS members were traitors. In: https://www.welt.de/ . Springer Verlag, April 23, 2019, accessed on December 3, 2019 .

- ↑ dpa: Brown was the color of the Nazis during the Nazi era. In: https://www.zeit.de/ . dpa / Die Zeit, November 17, 2011, accessed on December 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Georg Franz-Willing: Origin of the Hitler Movement 1919–1922. 2nd, improved edition. KWSchütz-Verlag , Preußisch-Oldendorf 1974, ISBN 3-87725-071-3 , p. 127.

- ^ Karl WH Koch: The book of honor of the SA. Ms. Floeder, Düsseldorf 1934, p. 48.

- ^ Roman Köster: Hugo Boss, 1924–1945. The story of a clothing factory between the Weimar Republic and the “Third Reich”. Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-61992-2 , p. 41.

- ↑ Look it up! Bibliographical Institute, Leipzig 1938, p. 203.