Tutankhamun

| Name of Tutankhamun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

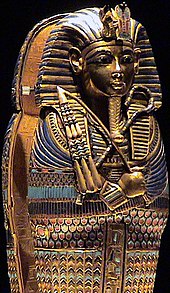

The death mask of Tutankhamun in the Cairo Egyptian Museum

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

K3-nḫt-twt-mswt Strong Taurus, with perfect births / completed at (re) births |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Nfr-ḫpw-sgrḫ-t3.w (j) With perfect laws that calm the two countries

Wr-ˁḥ-Jmn The great of the palace of Amun

Nfr-ḫpw-sgrḥ-t3.w (j) -s-ḥtp-nṯr.w-nbw With perfect laws, who calms the two countries, who the gods satisfies and makes peace |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Wṯs-ḫˁw-s-ḥtp-nṯr.w He who raises the crown, who pleases the gods

Wṯs-ḫˁw-jt = f-Rˁ Who raises the crowns of his father Re |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Nb-ḫprw-Rˁ Lord of Gestalten, a Re

Nb-ḫpw-Rˁ-ḥq3-m3ˁ.t master of figures, a Re, ruler of the mate |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

(Tut anch Aton) Twt ˁnḫ Jtn Living image of Aton later changed proper name:

(Tut anch Amun) Twt ˁnḫ Jmn Living image of Amun

(Tutankhamun heqa Iunu schema) Twt ˁnḫ Jmn ḥq3 Jwnw šmˁj Living image of Amun, ruler of the southern Junu ( Heliopolis ) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Chebres, Khebres Rathotis |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tutankhamun (including Tutankhamun , originally Tutanch Aton ) was an ancient Egyptian king ( Pharaoh ) of the 18th Dynasty ( New Kingdom ), the v about 1332-1323. Ruled. He became known when Howard Carter discovered his almost unlooted grave ( KV62 ) in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 .

family

parents

The archaeologist and former General Secretary of the Supreme Council of Antiquities , Zahi Hawass , had had fragments of a block from Hermopolis searched in the magazine for further investigation in order to prove the parenthood of Tutankhamun , the inscription of which reads: Son of the king in his womb, loved by him, Tut -anchu-aton . The block had already been published in 1969 after it was discovered by Günther Roeder and other employees of the German Hermopolis expedition during the excavations in Hermopolis (1929–1939) . The inscription shows Tutankhamun (here still Tutanchaton ) as the son of an unnamed king, but the inscription on the block names Tutankhamun as well as his sister Ankhesenpaaton . However, the part of the block is badly damaged, which is why the name of Anchesenpaaton could only be deduced, but must point to Akhenaten as the father for both royal children , since Ankhesenpaaton is evidently indicated as Akhenaten's daughter in other inscriptions. Zahi Hawass was already convinced in 2008 before the DNA analysis carried out in 2010 that only Akhenaten could be considered as the father of Tutankhamun. The DNA analysis of 2010 confirmed this assumption, also made by numerous other Egyptologists .

A CT scan showed that the identified person from grave KV55 died between the ages of 35 and 45. Earlier estimates were based on a younger age. Zahi Hawass explained that, in combination with the inscription, there was no doubt that the person from grave KV55 was Akhenaten and thus Tutankhamun's father. The female mummy KV35YL from grave KV35 , referred to as the “ Younger Lady ”, could not only be identified as Tutankhamun's mother, but also as the sister of the mummy from KV55. The name is currently unknown, but motherhood is proven.

Concerning the reliability of the DNA analysis, doubts were expressed that the test results could contain some uncertainties due to the age and possible contamination of the samples. As the sole evidence, they would not allow proper identification. So far, Queen Nefertiti , her daughter Maketaton or Akhenaten's concubine Kija have been suspected as possible mothers. In Saqqara ( Bubasteion ) is the tomb of Maia , who was demonstrably Tutankhamun's wet nurse.

siblings

According to the previous findings about Tutankhamun's origins, he had at least six sisters / half-sisters: Meritaton , Maketaton , Anchesenpaaton , Neferneferuaton tascherit , Neferneferure and Setepenre . The assignment of the semenchkare to the family situation , which is often viewed as a brother / half-brother, is uncertain .

Wife and children

Tutankhamun's great royal wife was Ankhesenamun (originally called Ankhesenpaaton), daughter of Akhenaten and thus a sister or half-sister of Tutankhamun.

There are no finds that prove by inscriptions that Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun had children. The two fetuses found and mummified in his grave, a premature birth and a stillbirth, were considered his daughters. However, this was not considered certain, as a large number of objects from the Amarna period were found in Tutankhamun's tomb as well as in KV55 , so that the fetuses could possibly also have been removed from a tomb in Amarna . Such a close relationship (father / daughter) could only be assumed from the facts of the find.

The results of DNA tests published in February 2010 finally revealed that both child mummies were almost certainly Tutankhamun's daughters. The mother of both fetuses is the mummy KV21A from grave KV21 . So far this could not be genetically confirmed as the daughter of the mummy from KV55, which is regarded as Akhenaten. It is therefore uncertain whether this mummy is Tutankhamun's wife Ankhesenamun.

Domination

Tutanchaton ascended the throne of Egypt four years after Akhenaten's death. In between there was probably a three-year reign of the Semenchkare or a ruler with the throne name Ankh-cheperu-Re . The identities of these two people are unknown. It is sometimes assumed that Akhenaten's royal wife Nefertiti is hidden behind both names .

Due to his very young age, there is a presumption that the child king was strongly influenced by the pressure of the priesthood, high officials and probably also by Eje , who carried the title “Father of God”. The underage king could easily be persuaded to restrict the worship of the god Aton and to restore the conditions before Akhenaten's "revolution". This can be seen in the gradual turning away from the cult of Aton at the beginning and during his reign. Tutankhamun assumes the throne name "Neb-cheperu-Re" on his accession to the throne and is married to Ankhesenpaaton , Akhenaten's third daughter, who was thus his sister or half-sister.

He changed his maiden name from Tutanch aton ("living image of Aton") to Tutanch amun ("living image of Amun" or "in honor of Amun") and that of his wife from Ankhesen paaton ("she lives for / through Aton") in Ankhesenamun (“she lives for / through Amun”). After Akhenaten's newly founded capital Akhet-Aton (Tell el-Amarna) gave up in the second year of his reign , the royal court moved to Memphis ; not according to Thebes , as is often wrongly read.

The most important evidence of the policy carried out under Tutankhamun is his “Stele of the Restoration”, which was later seized by Haremhab and found in Karnak . It describes the decline of the empire under Aton, and he proclaims the return to the old gods. The young pharaoh has the temples of the old gods restored throughout the country. In the Temple of Luxor , the decoration of the colonnade is being completed, Karnak is getting two new chapels, and work is being done on the Sphinx avenue again. In Medinet Habu he is building his mortuary temple (perhaps the former temple of Ankh-cheperu-Re ). From Giza to Nubia there are indications of its construction activity. However, some of these monuments are later usurped by Haremhab as well.

However, the transition from the Amarna period did not take place suddenly: In Tutankhamun's tomb there are numerous objects on which the classic motif of the Amarna period - aton as a life-giving sun disk - can be seen. The most famous example is the throne chair that Tutankhamun used in his first years of reign. The Amarna period also has a long-lasting effect on art, which is particularly evident in the elements of statics and perspective. Thus, a forced departure from the old religious course is very unlikely, because in this case there would have been an iconoclasm , whereby care would have been taken to delimit oneself precisely from the old styles. There are numerous connections, so that Egyptologists also count the pharaohs Tutankhamun and Eje to the Amarna period (sometimes differentiated by after Amarna ).

In addition to Eje and Haremhab, various other officials under Tutankhamun are attested. The southern vizier was a certain Usermonth , and Pentu was another vizier, who so far is only attested by a pot inscription in Tutankhamun's tomb. Another important person was Maya , the treasurer , whose tomb was found in Saqqara and which was richly decorated with reliefs . The chief asset manager was Iniuia , and the viceroy of Kush was Huy , who is best known for his magnificently decorated grave in Thebes. Amenemone was the head of the royal workshops and goldsmiths. Nachtmin was another general. Sennedjem was "Head of Teachers".

death

Cause of death

The CT examination of January 6, 2005 showed an age of death of 18 to 20 years and corresponded to earlier scientific estimates by the anatomist Douglas E. Derry (1882–1969) of the University of Cairo , the radiologist Ronald George Harrison (1921–1983) of the University of Liverpool , the dental surgeon Frank Filce Leek (1903–1985) from the University of Manchester and the biologist and Egyptologist Renate Germer from the University of Hamburg . However, Leek referred to an entry in Carter's diary dated November 14, 1925:

"The results of Drs. DERRY and BEY's study (.....) has enabled them to give a definite pronouncements to the age of Tut-ankh-Amen. This controversial question has now been settled and his age definitely fixed between the limits of 17 or 19 years of age "

The assumption of an age of 23-27 years, for example by Gabolde, Wente and Harris, was thus refuted. On this occasion the then General Secretary of the Egyptian Antiquities Administration , Zahi Hawass , once again complained about the poor condition of the mummy, which he attributed to the improper treatment by Howard Carter.

The burial date can be narrowed down to the period from mid-March to early May, as flowers were found as grave goods that only bloom during this time of year. Between the end of December 1324 BC And mid-February 1323 BC. Chr. Death must have occurred, the period of which could be determined taking into account the seventy days of embalming . Bob Brier explained in his book The Tutankhamun Murder that the death was caused by external violence. He assumed an unnatural cause of death. He proved this with old x-rays showing an injury to the skull. This was very controversial in Egyptologists' circles, but also among medical professionals, as it was a misunderstanding: the X-ray shows a fragment of bone that came off after death.

During the CT examination in 2005 it was found that Tutankhamun's death could not have been a blow to the head, since no injuries to the skull caused in this way could be found. To everyone's surprise, a hitherto undiscovered thigh fracture of the left leg was found. Some specialists on the same team also found a fracture in the lower left thigh, as well as a fracture in the right kneecap and right lower leg. The finding suggests that the fractures were caused by an accident before Tutankhamun's death; There were no indications of a murder. Most Egyptologists now assume a hunting accident that caused Tutankhamun's later death. Zahi Hawass agreed with this thesis and vigorously denied the seriousness of a murder theory, which, however, is in contrast to earlier statements. However, these do not have to have a serious basis and can be based on other motives (press, tourism).

There was also a pressure injury that could have been caused by a blow or a tumor. Brier opted for a punch, but it was a fallacy - as determined by the 2005 CT scan. The missing sternum and the missing ribs of the mummy were still present after the recovery of Carter and Carnarvon. A photo that was taken immediately before Tutankhamun was reburied after Carter's investigations shows the mummy still in an intact condition. According to new knowledge, the damage was caused by grave robbers during the Second World War. In order to get to the pieces of jewelry, which were firmly attached to the mummy by the embalming resin , the ribs and the breastbone had to be sawed out. The CT examination confirmed this process, since no breaks, but rather smooth separations were found.

After further examinations of the old x-rays, the examining radiologist Richard Boyer had already concluded that Tutankhamun suffered from scoliosis (deformation of the spine). Those involved in the computed tomography examination from 2005 could not confirm a scoliosis and suspected that the undoubted slight deformation of the spine was caused by the mummification. A CT and DNA examination from 2010, however, agreed with Boyer and found that Tutankhamun - like close relatives including his father, presumably Akhenaten - had suffered from mild scoliosis; the mummy of his great-grandmother Tuja was even found to have a severe form. In addition, the 2010 examination also revealed other bone diseases in Tutankhamun (e.g. Köhler-Albau's disease type II ) and his close relatives. Boyer had also radiographically diagnosed Klippel-Feil syndrome (merging of several cervical vertebrae), but neither the CT examination in 2005 nor the DNA and CT examinations five years later gave a statement. Finds such as the limestone relief known as “Walk in the Garden”, which according to established opinion shows Tutankhamun with a walking stick and anchesenamun, also led to a debate about the king's orthopedic health.

Zahi Hawass assumes that the king died of a malaria infection , as gene segments of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum were discovered. Christian Timmann and Christian Meyer, scientists at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, doubt this and suspect that he died of sickle cell anemia . They published convincing evidence for this cause of death. The offer of cooperation between Timmann and Meyer with Zahi Hawass and the Egyptian Antiquities Authority was rejected in a letter from Hawass to Christian Meyer.

A new study, which took into account the distorting influence of overheating of the corpse due to the embalming process on previous analysis results, came to the conclusion in 2013 that Tutankhamun - as previously suspected - had died in an accident, probably in a chariot race, at least not from the skull injury that occurred postmortem. In contrast to the usual ancient Egyptian mummification practice, the heart of Tutankhamun is said to have been removed, which led to the assumption that it could have been so badly injured in an accident and, according to the ideas of the time, would no longer have been usable in the afterlife. ORF.at quotes a documentation from Channel4 (from Nov. 10, 2013) based on a recent British study that an "incredible chemical reaction" of the embalming oils led to the spontaneous combustion of the oils or the corpse shortly after its burial in the sarcophagus. Douglas E. Derry pointed out this chemical reaction as early as 1925 when he examined the mummy.

Representation in the grave

The names of the Pharaoh, his wife and his successor Eje - like that of all Amarna kings - were soon deleted from all official documents by Haremhab or Seti I and scratched off the walls, so that they do not appear in any king lists. On Amenhotep III. Haremhab follows directly there. The grave escaped the complete pillage because the entrance with overburden from the excavation of the grave of Ramses VI. was buried. However, people must have managed to break into the grave at least twice beforehand.

For a long time it was assumed by experts that - although Tutankhamun is said to be in the vicinity of his grandfather Amenhotep III. wanted to be buried - his highest adviser and successor Eje II had him buried in a small grave (KV62) in the Wadi Biban el-Muluk ( Valley of the Kings ), which was not originally intended for a royal burial . After more recent considerations, however, Egyptologists came to the view that Tutankhamun's tomb (KV62) was intended as such for him from the beginning, since a nearby tomb (KV55) was proven to be that of the Kija.

His successor and closest paternal advisor Eje arranged the funeral for Tutankhamun, and he is represented as his successor at the mouth opening ceremony in his burial chamber, which was laid out with the paintings and inscriptions during the very young Pharaoh's lifetime . Normally, when a pharaoh died, all work in his tomb was stopped, so such a representation should not exist. There are several ways to do this.

- Basically, nobody could have known beforehand that Tutankhamun would die at the age of 18; But Eje himself, more than 50 years old, should have expected not to survive this Pharaoh. This representation of the opening of the mouth ceremony, made before Tutankhamun's death, could be an indication that Eje had a hand in his early death. A Pharaoh who became increasingly self-confident over the years, who would then possibly also father a male successor, was not in his interest.

- Eje is represented as crowned, that is, the grave walls were made after his inauguration and thus after Tutankhamun's death. Tradition may have been broken in order not to lead the Pharaoh into the afterlife without sufficient protection and assistance. The hasty, almost sloppy work and the soot stains speak for it. The coronation after death, but before the burial of the old Pharaoh, can be explained by Eje's pursuit of royal dignity.

The treasures of the grave

→ Main article: KV62

When Howard Carter discovered the tomb in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 , news of it went around the world and sparked a great deal of interest that did not wane for a long time. The grave, initially declared as unopened, was relatively intact, as could be seen when the grave was opened on February 16, 1923 (opening of the wall between the anteroom with additions and the actual coffin chamber with sarcophagus). Tutankhamun, although only an insignificant king, had a plentiful supply of precious burial objects. As the only mummy of the Egyptian kings, Tutankhamun's mummy is currently in her grave, but was reburied in an air-conditioned plexiglass coffin to better protect it from environmental influences.

The grave goods can be roughly divided into two groups. There are objects that were specially made for the ruler's burial, and there are objects that seem to have been used in everyday life and then placed in the grave. The group of objects specially made for a burial includes the coffins, the canopic jars , but also a set of figures of gods in shrines, which are also known from other royal tombs of the New Kingdom and were previously only found at the burials of kings.

The group of everyday objects mainly includes furniture, headrests, some of the jewelry and other utensils. The addition of everyday objects to burials is a typical feature of the 18th dynasty (see: Grave goods (Ancient Egypt) ) and occurs only rarely before and later. For this reason, it can certainly be assumed that his grave was typical of his time, but probably more richly furnished with grave goods than the grave of important rulers such as Cheops or Sesostris I.

Golden grave goods

Many of the grave goods are made of wood decorated with gold leaf or pure gold, for example one of the most famous finds: the golden death mask of Tutankhamun. It covered the head, shoulders and chest and weighs a good 12 kilograms alone. The king is depicted wearing the Nemes headscarf typical of the 18th dynasty . The eyes rimmed with lapis lazuli are also a characteristic feature. Neither before nor later were death masks of comparable skill made. The outermost and middle coffins were gold-plated, while the innermost coffin, in which the mummy was located, is made of pure gold and weighs 110.4 kilograms. The four wooden shrines surrounding the sarcophagus as well as the smaller canopic shrine with the canopic box, other shrines and statues of the king and various deities were also gilded. The most famous statues are probably the life-size guardian statues from the antechamber, but only a small proportion of them are made of gold.

Another important find is the golden throne. The front of the backrest is provided with inlays made of semiprecious stones and silver and shows the anointing of the Pharaoh by his wife under the rays of the Aton , who each holds an ankh sign to the royal couple . The name of the god Aton is documented here as the “ new didactic name of Aton ”, which was used by Akhenaten from the 9th year of reign. In addition, it is noteworthy that the two armrests of the throne have both different variants of the king's name: on the inside of the left armrest the shape Tut-anch-Amun, on the outside of the right armrest the shape of Tut-anch-aton.

This scene is in the style of Amarna art, as known in the intimacy of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. The back of the backrest does not contain any inlays in gold leaf and shows ducks soaring from the papyrus thicket. The titles and names of the king and queen are given on the vertical wooden struts.

There were also many pieces of gold jewelry in the form of rings, earrings, bracelets or pectorals. Tutankhamun was also given items of clothing, including golden sandals tied with a string between his big toes.

Other additions

Other important burial objects were bows and arrows as well as several chariots dismantled into individual parts and other hunting utensils that the young king must have used on his hunting expeditions. A dagger blade made of meteor iron was also found in the burial chamber. Several writing palettes were also enclosed with the king, in which even dried paint was found. One bears the name of Meritaton, the eldest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, as well as the cartouche of Nefertiti, which identifies the pallet as an offering.

A large golden fan has become known among the abundance of other individual parts . This consists of a long rod with a semicircular, large two-dimensional attachment. Originally there were ostrich feathers in the upper attachment ; but after Carter and Carnarvon's regular invitation to visitors to pull hard on it (to see for themselves the stability with their own eyes), only the golden part ultimately made it to the museum. A wreath of flowers also fell victim to them. The grave researchers interpreted this romantically as the present from the grieving widow. For his physical well-being, the pharaoh was also given wine in jugs, 26 of which had been preserved. These are exactly the winery, often even the parcel of origin. For example, on jug No. 571 you can read the inscription sweet wine from the house of Aton from Karet, cellar master Ramose .

There were also trumpet-like brass instruments , the so-called " Scheneb " ( Šnb ), which are probably the oldest surviving examples. These instruments probably served as signaling instruments in the military field.

The two fetuses

Other important burial objects are the two mummified premature babies. On the other hand, according to popular opinion, these are not an isolated find; some other finds of mummified fetuses are known. The Italian archaeologist Ernesto Schiaparelli discovered 1903-1906 in the grave ( QV 55 ) of Amuncherchepeschef - a son of Ramses III - in the valley of the queens also a fetus, probably a child of Ramses III. The skeleton of a late fetus or a premature birth was also found in the shaft below the grave of Haremhab . There are also known burials of fetuses in a Roman cemetery in the Daleh oasis .

The two fetuses were found in the tomb of Tutankhamun in small coffins, which do not have the children's names, but simply designate them as " Osiris ", a title that every dead person wore. They are now held under inventory numbers "Carter 317a" and "Carter 317b" in the Medical Faculty of Cairo University .

317a is the smaller of the two fetuses and was in very good condition when it was discovered; it even had remains of the umbilical cord. The body was artificially mummified , so traces of mummified entrails were found in the body cavity and traces of embalming material in the skull. The hands of the fetus are placed on the inner thighs. Today, however, the mummy is in such a bad condition that no incision to remove the organs or damage to the skull to remove the brain could be detected. Even the statement from earlier studies that the fetus is female can no longer be confirmed today. The fetus is 29.9 cm and is estimated to be 24.5 weeks of age.

The larger fetus 317b was less well preserved when it was discovered, but is in better condition than 317a today. He is 36.1 cm tall and still has hair fluff, eyebrows and eyelashes. The hands are placed on both sides of the body. There is a 1.8 cm incision on the side of the mummy through which the entrails were removed. The brain was removed with a tiny instrument. This tool was so small that it was probably made specifically for the mummification of the fetus. The then examining medic, Douglas Derry, threw it away. The fetus lived to be 30-36 weeks old (the data differ depending on the examination) and was fully viable. However, it has some genetic anomalies: Sprengel malformation, the spinal dysphrasia syndrome and a slight scoliosis . The fetus is female.

Due to the poor state of preservation, proper DNA samples could not be taken from the fetuses. With fetus 317a they were so bad that no conclusive results could be obtained, with 317b, however, there is a 99.9% probability that it is a child of Tutankhamun. As the mother of the child, the mummy KV21a was identified as part of the 2010 King Tutankhamen Family Project . This could not be genetically assigned to a daughter of King Akhenaten and thus possibly Anchesenamun . Your identity has therefore not yet been clarified.

Interpretations

Many of the grave goods are articles of daily use for the king; in some cases he may have used them until his death, in some cases (like the children's throne from Amarna) they had not been in use for a long time. There are many grave goods bearing the names of Tutankhamun's relatives; a writing palette came - as described above - from the possession of Merit-Aton, as well as a children's rattle with a dedication to Queen Teje, as well as a box with the image and the name of Nefer-neferu-Re, the second youngest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti.

The finds from Amarna were brought here earlier, before the king's death. Near the Tutankhamun tomb is the tomb KV55, whose destroyed mummy, according to the findings of a CT examination, could most likely be that of Akhenaten. The contents of the tomb consist of items made of Amarna - from different owners. An expedition was probably sent to Amarna, which in addition to all these things also brought the mummies of Kija, Teje (grave KV35) and Akhenaten. After the reconstruction of the lid, the sarcophagus can be clearly assigned to Akhenaten.

It is not sufficiently clear whether the Egyptian custom included gifts from relatives in the grave, and whether the grave goods were newly made or objects of daily use were also taken. It is most likely that everyday objects (official insignia, for example) were taken along and some pieces were specially made for the afterlife.

There is, however, the possibility that Tutankhamun's tomb was filled in a rush and that there is not a conscious intention behind all things old or "given" . This could be supported by the evidence that the king's mummy was mummified in a very short time and possibly not sufficiently dried out. Furthermore, Christine El-Mahdy has proven that the wine jugs did not dry out over the centuries, but that they were already empty when they were placed in the grave.

The mysterious Dachamunzu affair , which may have followed Tutankhamun's death, is partly interpreted as a clever move by the royal advisor Eje , who wanted to get General Haremhab , who also acted as advisor, out of the way so that he does not claim the throne for himself could. In spite of everything, it is only one of several theory and there are other ways to interpret the evidence.

The curse of the pharaohs

In connection with the excavation work and the lively interest of the world press, the legend of the curse of the Pharaoh spread after the grave was discovered . Much has been said about the curse of the mummy, which supposedly hit the discoverers. Some members of Carter's excavation team died within the first five years of the excavation of the sarcophagus, including the financier of the KV62 excavation, Lord Carnarvon , who died of infection on April 5, 1923.

The causes of the deaths were investigated: Five members of the discovery team committed suicide based on the publications of the other deaths. Other causes were seen to be infections caused by mold spores in the air of the burial chamber or mosquito bites. Illnesses already existing when the grave was opened also led to death, which would have occurred even without connection to the grave. Statistical studies even showed an increased average age of all alleged victims.

The finds today

The main finds from the tomb, including the golden death mask, are in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and in magazines in Cairo and Luxor. The pharaoh's mummy is the only one of an Egyptian king that is still in the original tomb in the Valley of the Kings after the tomb was discovered and opened. In the course of the revolution in Egypt in 2011 , the Egyptian Museum was looted, which also affected the finds from Tutankhamun's tomb. A small gold-plated statuette ( JE 60710.1 ) and the upper part of another have been missing since then. Several other statues were broken but could be restored.

In January 2015 it became known that the death mask was damaged when the lighting fixtures on the armored glass showcase were replaced in August 2014: the pharaoh's beard broke off and was improperly reattached with resin glue. Glue dripped onto the mask, which was then scraped off and caused further damage. In early 2016, eight Egyptians were charged in this matter, including the former director of the Egyptian Museum and the then chief restorer. The mask has meanwhile been restored.

literature

German-language literature

- Hartwig Altenmüller : Papyrus thicket and desert: considerations on two statue ensembles of Tutankhamun In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) 47, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, pp. 11-19.

- Jan Assmann : Tutankhamun and his time. In: Thomas Schneider , Mirco Hüneburg: MA'AT - Archeology of Egypt, Issue 1. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1357-3 , pp. 24–33.

- Horst Beinlich: Concordance of the Tutankhamun catalogs. In: Göttinger Miszellen 71, Göttingen 1984, pp. 11-26.

- Horst Beinlich: The Book of the Dead at Tutankhamun. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 102, Göttingen 1988, pp. 7-18.

- Howard Carter , Arthur Mace: Tutankhamun. An Egyptian royal tomb. 3 vols., Leipzig 1927.

- Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt : Tut-Ench-Amun - Life and Death of a Pharaoh. Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1971, ISBN 3-548-04712-2 .

- Rosemarie Drenkhahn: A reburial of Tutankhamun? In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. 39, von Zabern, Mainz 1983, pp. 29-37.

- Marianne Eaton-Krauss: Tutankhamun as a hunter. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 61, Göttingen 1983, pp. 49-50.

- Christine El Mahdy : Tutankhamun. Life and death of the young pharaoh. Goldmann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-442-15260-7 .

- Zahi Hawass , Sandro Vannini: Tutankhamun. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-89405-711-4 (illustrated book: grave, sarcophagus, grave goods and history of discovery).

- Zahi Hawass: In the footsteps of Tutankhamun , Theiss, Darmstadt 2015.

- Dieter Kessler: About the hunting scenes on the little golden Tutankhamen shrine. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 90, Göttingen 1986, pp. 35-44.

- Klaus Köller: Comments on the "Reliefed gold sheet of Tutankhamun". In: Göttinger Miscellen. 13, Göttingen 1993, pp. 79-84.

- Christian E. Loeben : Figure concordance between the English and German editions of Carter's Tutankhamun publication. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 40, Göttingen 1980, pp. 69-80.

- Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the New Kingdom to the Late Period. Marix, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 978-3-7374-1057-1 , pp. 114–128.

- Hermann A. Schlögl : Akhenaten - Tutankhamun. Harrassowitz Collection, 1993, ISBN 3-447-03359-2 .

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 301-302.

- André Wiese, Andreas Brodbeck (ed.): Tutankhamun - The golden afterlife. Grave treasures from the Valley of the Kings. Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany , Bonn 2004, ISBN 3-905057-17-4 (catalog of the exhibition from November 4, 2004 to May 1, 2005).

Foreign language literature

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs, Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9 , pp. 479-481.

- Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt: Toutankhamon et son temps. In: Exhibition catalog of the Petit Palais (Paris) . Ed .: Ministère d'État des Affaires Culturelles and Ville de Paris, 1967.

- Jacobus van Dijk, Marianne Eaton-Krauss: Tutankhamun at Memphis. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. 42, von Zabern, Mainz 1986, pp. 35-41.

- Marianne Eaton-Krauss: Tutankhamun at Karnak. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. 44, von Zabern, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-8053-1039-0 , pp. 1-11.

- Hans Goedicke : Tutankhamun's Shields. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 140, Göttingen 1994, pp. 27-36.

- JR Harris: The Date of the "Restoration" Stela of Tutankhamun. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 5, Göttingen 1973, pp. 9-11.

- Erik Hornung : The New Kingdom. In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental studies. Section One. The Near and Middle East. Volume 83). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2006, ISBN 90-04-11385-1 , pp. 197-217. (on-line)

- Mary A. Littauer, Joost Crouwel: Unrecognized Linch Pins from the Tombs of Tutankhamun and Amenophis II: A Reply. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 100, Göttingen 1987, pp. 57-62.

- Boyo G. Ockinga: ti.t Sps.t and ti.t Dsr.t in the Restoration Stele of Tutankhamun. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 137, Göttingen 1993, p. 77.

- Robert B. Partridge: Tutankhamun's Gold Coffin: An Ancient Change in Design? In: Göttinger Miscellen. 150, Göttingen 1996, pp. 93-98.

- Nicholas Reeves : The Complete Tutankhamun - The King. The tomb. The Royal Treasure. Thames & Hudson, London 2000 (Paperback), ISBN 0-500-27810-5 .

- Nicholas Reeves: Tutankhamun and his Papyri. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 88, Göttingen 1985, pp. 39-46.

- Robert Ritner: Unrecognized Decorated Linch Pins from the Tombs of Tutankhamon and Amenhotep II. In: Göttinger Miszellen. 94, Göttingen 1986, pp. 53-56.

- Gay Robins: Two Statues from the Tomb of Tutankhamun. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 71, Göttingen 1984, pp. 47-50.

- Gay Robins: Isis, Nephthys and Neith Represented on the Sarcophagus of Tutankhamun and in four freestanding statues found in KV62. In: Göttinger Miscellen. 72, Göttingen 1984, pp. 21-26.

- Gay Robins: The Proportions of Figures in the Decoration of the Tombs of Tutankhamun (KV62) and Ay (KV23). In: Göttinger Miscellen. 72, Göttingen 1984, pp. 27-32.

Web links

General

- Literature by and about Tutankhamun in the catalog of the German National Library

- Marianne Eaton-Krauss: Tutankhamun. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical dictionary on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on September 3, 2008.

- Very comprehensive site about Carter's excavations, with original photographs, excavation diaries and complete list of all findings (English)

- Extensive Flash Player animation about Tutankhamum, with 3-D skull reconstruction and tomb paintings (English)

- Comprehensive explanations of the situation at that time for Tutankhamun and his wife Ankhesenamun with some very good pictures for illustration

For DNA testing

- Jan Dönges: paternity test for a mummy. DNA examination on Tutankhamun provides new findings. www.wissenschaft-online.de, February 16, 2010, accessed on March 27, 2011 .

- ZDF documentary May 24, 2010: Tutankhamun - the solution to the riddle

- JAMA: Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family - DNA test results in 2010 (English)

- Karin Schlott: Royal Mummies: Dispute over Tutankhamun. In: epoc 4/12. www.spektrum.de, November 29, 2012, pp. 76–81 , accessed on January 29, 2013 .

For CT examination

- Complete, official press release of the CT examination (English)

- Facial reconstruction of Tutankhamun from 2005 ( memento from June 30, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

Exhibitions

- Tutankhamun - His grave and the treasures - adventure exhibition with faithful replicas of the burial chambers and approx. 1000 replicas of the most important finds

- Tutankhamun, the Treasures of the Pharaoh - Last exhibition of original finds outside of Egypt

Individual evidence

- ^ Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume 1, London 2008, p. 479.

- ^ Reign after Josephus: 9 years. Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , p. 115.

- ↑ Dating after Rolf Krauss from: Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 318.

- ^ Günther Roeder: King's son Tut-anchu-Aton. In: Rainer Hanke: Amarna reliefs from Hermopolis (excavations of the German Hermopolis expedition in Hermopolis 1929–1939), Volume 2 . Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1969, p. 40.

- ↑ Zahi Hawass: King Tut was the son of Akhenaten. from 2009 ( Memento from November 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Information Service Science: Parents of Tutankhamun identified. On: idw-online.de from February 17, 2010; Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ Doubts about the results of the DNA analysis. On: focus.de from February 16, 2010; Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Zahi Hawass: DiscoveringTutankhamun. From Howard Carter to DNA. The University Press, Cairo 2013, ISBN 978-977-416-637-2 , p. 170.

- ↑ Note : the throne name Ankh-cheperu-Re is used by both Semenchkare and Neferneferuaton. There is also a feminine form of the name: Anch et -cheperu-Re.

- ↑ Frank Filce Leek: The human remains from the tomb of Tutankhamun (= . Tut'ankhamūn's tomb series Volume 5). Griffith Institute, Oxford 1972, p. 7.

- ↑ a b This fact was published at the press conference after the CT examination (see web link).

- ↑ Zahi Hawass, Yehia Z. Gad et al. a .: Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family. In: Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). 2010, Volume 303, No. 7, pp. 638-647, ("Reprinted with Corrections"), doi: 10.1001 / jama.2010.121

- ↑ E. Zahradnik: On the representation of a king with a pathological leg diagnosis on the relief "Walk in the garden". In: Palarch's Journal of Archeology of Egypt / Egyptology. Volume 6, No. 8, 2009, pp. 1-7. ISSN 1567-214X . ( (online) )

- ↑ Doubts about the alleged cause of Tutankhamun's death . On: Archeology Online. dated June 24, 2010; Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ C. Timmann, C. Meyer u. a .: King Tutankhamun's Family and Demise. In: Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). 2010, Volume 303, No. 24, Letters. P. 2473, doi: 10.1001 / jama.2010.822

- ↑ C. Timmann, C. Meyer: Malaria, mummies, mutations: Tutankhamun's archaeological autopsy. In: Tropical Medicine and International Health (TM&IH). 16. Aug. 2010, doi: 10.1111 / j.1365-3156.2010.02614.x (full text)

- ↑ shortnews.de 91 years after his discovery: Pharaoh Tutankhamun's cause of death probably revealed . On shortnews.de of November 3, 2013; Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ History Doc: Tutankhamun Mysteries of a Burial Chamber Documentary HD. Accessed December 30, 2018 .

- ↑ British researchers: Tutankhamun died in a car accident. On: ORF.at from November 10, 2013 ( Memento from November 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Griffith Institute, Oxford: AC Mace's account of the opening of the burial chamber of Tutankhamun on February 16, 1923 ( Memento of January 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Charges for sticking Tutankhamun's beard on. On: Deutschlandradio Kultur. - News of January 24, 2016.

- ↑ Horst Beinlich, Mohammed Saleh: Corpus of the hieroglyphic inscriptions from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-900416-53-X , No. 91, p. 36.

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg Germany: Meteorite material: Tutankhamun's dagger comes from space. In: SPIEGEL ONLINE. Retrieved June 3, 2016 .

- ↑ Daniela Comelli, Massimo D'orazio, Luigi Folco, Mahmoud El-Halwagy, Tommaso Frizzi: The meteoritic origin of Tutankhamun's iron dagger blade . In: Meteoritics & Planetary Science . May 1, 2016, ISSN 1945-5100 , p. n / a – n / a , doi : 10.1111 / maps.12664 ( wiley.com [accessed June 3, 2016]).

- ↑ H. Beinlich, M. Saleh: Corpus of the hieroglyphic inscriptions from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1989, No. 262.

- ^ Contents Box 272; photographed by Harry Burton around 1927, Heilbrunn timeline of art history. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY January 2009, at: metmuseum.org . ( Memento from September 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Manfred Dworschak: Viticulture - raster search underground. In: Der Spiegel. Issue 23/2006, p. 175.

- ↑ Zahi Hawass: In the footsteps of Tutankhamun . Theiss, Darmstadt 2015, p. 168 .

- ↑ on Merit-Aton as already described, on the children's rattle: H. Beinlich, M. Saleh: Corpus of the hieroglyphic inscriptions from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Griffith Institute, Oxford 1989, No. 620 (p. 13); to the box of the Nefer-neferu-Re: No. 54 hh.

- ↑ International Association of Egyptologists (IAE): List of missing artifacts from the Egyptian Museum Cairo ( PDF; 748 kB ( Memento from January 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive )) On: sca-egypt.org from March 15, 2011 ; Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Zahi Hawass: Sad News. On: drhawass.com ( Memento from November 24, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Looters destroy Tutankhamun treasures. on: spiegel.de from January 30, 2011; Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ Maybe they should have taken Pattex. A conversation with the restorer Christian Eckmann, in: FAZ No. 23, January 28, 2015, p. 9.

- ↑ Damaged death mask: Tutankhamun's beard hastily glued on with glue : spiegel.de , January 22, 2015; Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ Charges for sticking Tutankhamun's beard on . On: deutschlandradiokultur.de (Deutschlandradio Kultur - Nachrichten) from January 24, 2016.

- ↑ Guido Mingels: Egyptology: The Pharaoh's Surgeon . On spiegel.de ( Der Spiegel ) from December 19, 2015; Retrieved January 25, 2016.

| Contemporaries of Tutankhamun (1333–1323) | |||

| Hittites | Assyria | Mittani | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Šuppiluliuma I. (1355–1323) | Aššur-uballit I. (1353-1318) | Šattiwazza (1350-1320) | |

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Semenchkare |

Pharaoh of Egypt 18th Dynasty |

Eje II. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tutankhamun |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tutanchaton, Neb-cheperu-Re |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Egyptian Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 14th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 14th century BC Chr. |