1. Amendment to the United States Constitution

The first Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America ( English First Amendment ) is part of the Bill of Rights designated list of fundamental rights of the Constitution of the United States. The article, passed in 1791, forbids Congress from passing laws that restrict freedom of speech , freedom of religion , freedom of the press , freedom of assembly, or the right to petition . The article also prohibits the introduction of a state religion and the preferential treatment or disadvantage of individual religions by federal law.

Although the wording of the article only restricts Congress, the Supreme Court has ruled in several rulings that this restriction also applies to the states due to the 14th Amendment .

text

The original text of the 1st Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America is (with German translation):

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. "

“Congress should not pass any law that has as its object or restricts the freedom to practice any institution, freedom of speech, freedom of the press or the right of the people to peacefully assemble and petition the government for an end to grievances to judge, restricts. "

The 1st Amendment is as adopted by the US Congress legislative document as the third item ( english Article the third ) listed.

history

The constitution, as originally ratified, aroused some opposition because it did not adequately guarantee civil rights. In response, the first amendment to the Constitution, along with the rest of the Bill of Rights, was proposed by Congress in 1789 . On December 15, 1791 , the Bill of Rights had been ratified by the necessary number of states and thus passed.

Interpretation by the courts

The Supreme Court has over time established rules for the constitutionality of laws in accordance with the first Amendment. Subordinate federal courts and courts of the individual states are required to follow these rules in their interpretation of the federal constitution. Such classic expressions as clear and present danger , without redeeming social value and wall of separation between church and state (“clear and acute danger”, “without compensatory social value” and “dividing wall between church and state”) are not in the text of the Constitution, but were important in court decisions and also found their way into current legal practice.

Establishment of a state religion

The so-called establishment clause , (for example: " establishment clause ") forbids the Congress to introduce a state religion. Before Amendment 14 came into effect , the Supreme Court generally held that the essential rights and prohibitions contained in the Bill of Rights did not affect state activities . Subsequently, some selected regulations were also related to the federal states through the incorporation doctrine (for example: “insertion doctrine ”). However, it was not until the second half of the twentieth century that the Supreme Court began to interpret the clauses that forbade the establishment of a state religion and guaranteed freedom of worship, so that state government subsidies for certain religions were substantially reduced. For example, the judge came David Souter in 1994 to the fall in the judgment Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumble at the end:

"Government should not prefer one religion to another, or religion to irreligion."

"The government should neither prefer one religion to another, nor religion over the absence of religion."

Free exercise of religion

The freedom to practice one's religion clause has often been interpreted to include two freedoms: the freedom to believe and the freedom to act. The first freedom is absolute, while the second is often restricted by the state. The Jehovah's Witnesses , a religious group, were often the target of such a restriction. Several cases, including those involving Jehovah's Witnesses, allowed the Supreme Court to discuss the freedom of worship clause at length. Under Chief Justice Earl Warren , a generous interpretation of the clause was introduced, the compelling interest doctrine (for example: "Doctrine of compelling interest"). According to this doctrine, the state must demonstrate that it is of overriding interest to restrict religious activities. However, later decisions have reduced the scope of this interpretation.

freedom of speech

Incitement to riot

Notably, until the beginning of the twentieth century, the Supreme Court did not handle a single case in which it was asked to check the constitutionality of a law against the clause of the first amendment guaranteeing freedom of expression. The constitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts has never been challenged in the Supreme Court, and even the leading critics of these laws, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison , only argued that the laws were unconstitutional based on the 10th Amendment rather than the First Amendment.

After the First World War , laws restricting freedom of expression were the subject of several trials in the Supreme Court. The Espionage Act of 1917 provides for a maximum penalty of 20 years ago to anyone who insubordination , disloyalty, mutiny or conscientious objection in the land or naval forces of the United States ( English insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty in the military or naval forces of the United States ) caused or attempted to cause. The prosecution of over two thousand people has been initiated because of this law. For example, a filmmaker was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment for alleging malicious intentions of a United States ally, the United Kingdom , for portraying British soldiers in a film about the American independence movement . The Sedition Act went even further and made "faithless" ( English disloyal ), "grossly vulgar" ( English scurrilous ) and "abusive" ( English abusive ) statements about the government prosecution.

The Supreme Court was first established in 1919 in the Schenck v. United States requests to declare unconstitutional law violating freedom of expression. Charles Schenck was involved in the case, who had distributed leaflets during the war in which he had challenged the conscription system of the time. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld Schenck's conviction for violating the Espionage Act . The judge Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. , who acted as clerk in the process, stated:

"The question in every case is whether the words used are in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent."

"In any event, the crucial question is whether the words that have been used in such circumstances are of the nature that they create a definite and acute danger and that they cause the essential evils that Congress may lawfully prevent."

The test for clear and acute danger from the Schenck trial was expanded again by Oliver Wendell Holmes in another trial. That process involved a speech by Eugene V. Debs , a political activist. Debs hadn't said a single word in it that posed a definite and acute danger to the conscription system, but in his speech he praised, among other things, those who had been imprisoned for obstructing conscription. Judge Holmes pointed out that Debs' speech had "obvious intent" ( English natural tendency ) to prevent his draft.

In this way, the Supreme Court interpreted the First Amendment as allowing a large number of restrictions on freedom of speech. Further restrictions on freedom of speech was in 1925 in the case v Gitlow. New York accepted. Judge Edward Sanford spoke for the majority of the judges when he suggested:

"And a state may penalize utterances […] [which], by their very nature, involve danger to the public peace and to the security of the state."

"And a state may punish utterances [...] [which] by their nature lead to danger for public peace and for the security of the state."

The legislators were allowed to decide for themselves which statements would create such a danger.

During the Cold War , freedom of expression was influenced by anti-communism . In 1940 , Congress reinstated the sedition law that had expired in 1921 . The Smith Act , passed that year, said:

"It shall be unlawful for any person to […] advocate […] [the] propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force and violence."

"It is unlawful for any human being to advocate the overthrow of any United States government."

The law was mainly used as a weapon against communist leaders . The constitutionality of the law was in the Dennis v. United States challenged. The Supreme Court upheld the bill 6-2 (one judge, Tom C. Clark, did not vote for having previously ordered prosecutions under the Smith Act in his previous position as Attorney General ). Chief Justice Fred M. Winson relied on the test of definite and acute danger designed by Oliver Wendell Holmes as he spoke for the majority of the judges. Winson noted:

"Obviously, the words cannot mean that before the Government may act, it must wait until the putsch is about to be executed, the plans have been laid and the signal is awaited."

"Obviously, the words cannot mean that before the government can act, it has to wait until the coup is about to be carried out, until the plans are made and just waiting for the signal."

By this statement he defined the words clear and acute danger in general. Therefore, Communist Party speeches that violated the Smith Act while not posing a direct threat were banned by the Supreme Court.

The verdict in the case of Dennis v. United States has never been expressly overturned by the Court, but subsequent decisions have effectively reversed the case. In 1957 the court changed its interpretation of the Smith Act when it opened the Yates v. United States treated. The Court decreed that the law on "the advocacy of action, not ideas" ( english the advocacy of action not, ideas ) aimed. Thus the defense of abstract doctrines remains protected by the first amendment. Only speech expressly inciting the violent overthrow of the government remains punishable by the Smith Act .

Under Chief Justice Earl Warren , the Supreme Court expanded the protection of freedom of expression in the 1960s , although there were exceptions. In 1968 , for example, in the United States v. O'Brien passed a law that prohibited the mutilation of military passes. The Court decreed that the complainants Defense passports should not burn, because it interferes with the "smooth and speedy functioning" ( English smooth and efficient functioning ) of the system convening einwirke.

In 1969 the Supreme Court ruled in the Tinker v. Des Moines that freedom of expression also applies to students. The case involved several students who had been punished for wearing black bracelets to protest the Vietnam War . The court ruled that the school could not prohibit symbolic language that did not cause inappropriate interruptions in school activities. Judge Abe Fortas wrote:

“State-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism. School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students [...] are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State. "

“Public schools must not be enclaves of totalitarianism . School officials have no absolute authority over their students. The students [...] have basic rights that the state must respect, just as the students must respect their obligations to the state. "

The decision was made in 1986 by the Bethel School District v. Fraser arguably dismissed, or at least undermined, as the Supreme Court in this case ruled that a student could be punished for speaking at a public meeting.

In 1969 the court also decided the Brandenburg v. Ohio , which passed the judgment of the Whitney v. California dismissed a 1927 trial in which a woman was sentenced to imprisonment for supporting the Communist Party . The case of Brandenburg v. Ohio also overturned the judgment from the Dennis v. United States by clearly granting the right to speak freely from violent acts and revolution:

“[Our] decisions have fashioned the principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action. "

“[Our] decisions have found expression in the principle that the constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and freedom of the press do not allow a state to forbid or outlaw the advocacy of the use of force or the violation of a law. An exception to this is the case that this advocacy is aimed at stimulating or producing threatening lawlessness and there is a high probability that such actions are actually stimulated or produced by this advocacy. "

Some claim that the verdict from the Brandenburg v. Ohio is essentially rewriting the test for clear and acute danger, but the veracity of such statements is difficult to judge. The Supreme Court has v since the judgment of Brandenburg. Ohio no longer heard or decided a case the subject of inflammatory speeches was.

The issue of burning the US flag , which caused great disagreement, came with the fall of Texas BC in 1989 . Johnson before the Supreme Court . The Supreme Court overturned Gregory Johnson's conviction for burning the US flag by five votes in favor to four against. Judge William Joseph Brennan argued :

"If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea offensive or disagreeable."

"If there is a rationale of the First Amendment, it is the principle that forbids the government from prohibiting the expression of an idea solely on the basis of the fact that society finds that idea offensive and obnoxious."

Many members of Congress vilified the court's decision. The House of Representatives unanimously passed a resolution denouncing the court; the Senate did the same with only three no votes. Congress passed law prohibiting the burning of the flag, but the Supreme Court declared it in 1990 in the United States v. Eichman also found it unconstitutional. There have been several attempts to amend the constitution to allow Congress to prohibit the desecration of the flag. Since 1995 , the constitutional amendment regarding desecration / burning of the flag ( English Flag Desecration Amendment or Flag Burning Amendment ) has repeatedly received sufficient votes to be passed in the House of Representatives, but could not achieve the required number of votes in the Senate. In 2000 , the Senate voted 63 in favor of 37 against, which was four votes too few for the required two-thirds majority. The last time this addition was passed during the term of office of the 109th Congress with 286 for, 130 against and 18 abstentions on June 22, 2005 in the House of Representatives.

Profanity

The US and state governments have long been allowed to restrict obscene or pornographic language. While obscene language is generally not protected by the First Amendment, pornography is subject to some regulation. However, the exact definition of profanity and pornography has changed over time. Judge Potter Stewart is the author of the famous statement that, although he could not define pornography, while apparently recognize ( English I know it when i see it. ).

When John Marshall Harlan in 1896 in the case of Rosen v. United States delivered the verdict, the Supreme Court established the standard of profanity set in the famous British Regina v. Hicklin had been set up. The Hicklin standard was as follows:

"[Material is obscene if it has] the tendency […] to deprave or corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall."

"[Something is obscene when it] tends [...] to corrupt and harm those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands such publications may fall."

Thus, the standard of the most sensitive members of society was the standard for profanity. In 1957, in the Roth v. United States that the Hicklin test was inappropriate. The Roth test was introduced in its place:

"[The test of obscenity is] whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest."

"[The test of profanity is] whether the main theme of the material as a whole appeals to the indecent interests of the average person, given current social standards."

As the Court in 1973 in the case v Miller. California decided the test was expanded. According to the Miller Test , a work is obscene if it appeals to the indecent interests of the average person when current social standards are taken into account, portrays sexual conduct in a manifestly offensive manner, and has no serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific merit. It should be noted that the social standard - not the national standard - must be considered when assessing whether the material appeals to lewd interest; therefore, it is possible that a work may be considered obscene in one place but not in another. On the other hand, national standards are applied when assessing the question of whether the material has any value. Child pornography is subject pursuant to a ruling by the Supreme Court of 1982 is not the Miller test. The Court found the government's interest in protecting children from abuse a priority.

However, private ownership of obscene material cannot be prohibited by law. As rapporteur in the Stanley v. Georgia wrote to Judge Thurgood Marshall :

"If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man sitting in his own house what books he may read or what films he may watch."

"If the first amendment says anything, it says that it is not the business of the state to tell someone who is in their own house which books they can read or which films they can watch there."

However, it is not unconstitutional for the government to prohibit the shipping or sale of obscene works, even if they were only viewed privately. The verdict of the Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition of 2002 the above rights was further maintained by the law for the prevention of child pornography of 1996 abrogated and testified:

"Banning the depiction of pornographic images of children, including computer-generated images, was overly broad and unconstitutional under the First Amendment."

"The ban on the display of child pornography images, including computer-generated images, was overly comprehensive and, due to the first amendment to the constitution, unconstitutional."

Judge Anthony M. Kennedy wrote:

“First Amendment freedoms are most in danger when the government seeks to control thought or to justify its laws for that impermissible end. The right to think is the beginning of freedom, and speech must be protected from the government because speech is the beginning of thought. "

“The freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment are most at risk when the government tries to control the mind or to direct its laws towards that inadmissible goal. The right to think is the beginning of freedom, and language must be protected from the government because language is the beginning of thinking. "

US courts have upheld a certain regulation of pornography because they believed that regulating and banning pornography as a way to protect children was the test that requires rigorous and scrutiny. A law of differentiating regulation that limits the places where pornography can be viewed can be valid if the law is aimed primarily at secondary effects, the differentiation is unrelated to the suppression of pornographic content, and the law has other options for the Viewing the content creates.

Defamation and Private Lawsuit

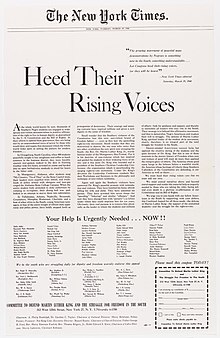

The US ban on defamatory speech and slanderous publications can be traced back to English law. The interpretation of the Defamation Act was changed significantly by the Supreme Court in 1964 when it came to the New York Times Co. v. Sullivan gave the verdict. Together with the decision in the New York Times Co. United States (1971), regarding the Pentagon Papers , which marked the suppression of information as unconstitutional even before publication, Sullivan is considered to be one of the most important judgments in the area of press freedom.

The New York Times published a full-page ad on March 29, 1960, from supporters of pastor and Civil Rights Movement activist Martin Luther King, Jr. , which contained several factual errors: It was alleged that King was arrested seven times in Montgomery , Alabama , in fact it was four times; the police officers there had surrounded Alabama State College , in fact they only gathered nearby, and because of the civil rights demonstration, they had not been there either; Ultimately, the students would not have sung the song that was mentioned in the ad. The allegation that police officers brutally suppressed protests by African Americans during the American civil rights movement was not criticized .

The unnamed LB Sullivan, one of the three Public Safety Office commissioners responsible for the Montgomery Police Department, then sued the Times for defamation on the grounds that the article was damaging the reputation of the Montgomery Police Department. The Times was found guilty by Alabama state courts and sentenced to $ 500,000 in damages - courts across the southern states had already ordered civil rights activists and their organizations, journalists and publications $ 300 million in libel charges.

The Supreme Court overturned the ruling against the Times by 9 votes to 0. In particular, it was found that if a plaintiff in a defamation process is a civil servant or a person running for public office, he must not only demonstrate the normal elements of defamation - the publication of a false defamatory statement against a third party - but also prove that the statement was made with actual malice , which means that the accused either knew the alleged defamation was false or recklessly disregarded the truth. The term actual malice was found in the Alabama Supreme Court decision; in the case law of the US Supreme Court he was found only once before Sullivan .

The requirement to prove actual malice applies to both civil servants and well-known people, including celebrities. Although the details vary from state to state, private individuals usually only need to prove culpable conduct on the part of the defendant; but see Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. one paragraph below.

Justice Black criticized:

“'Maliciousness,' even as defined by this court, is an abstract term difficult to prove and difficult to disprove. The requirement that malice has to be proven offers at best a fleeting (in the original: evanescent ) protection for the right to critically discuss public affairs, and certainly does not meet the robust security precautions contained in the First Amendment . "

In 1974 the Supreme Court ruled in the Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. stated that opinions should not be regarded as defamatory. According to this judgment, for example, it would be permissible to claim that a lawyer is bad, but it would not be permissible to state that this lawyer is ignorant of the law: the first statement is judgmental while the second relates to facts.

A few years later, in 1990, in the Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co. , the Supreme Court distanced itself from the protection of opinion, which it provided in the Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. had set up. The Court specifically stated that statements stamped as opinion were not exempted from the Defamation Act in general, but that a statement must instead be falsifiable before it could be the subject of a defamation process.

In 1988 the actual malice request was made in the Hustler Magazine v. Falwell of the Supreme Court, who protected a parodic caricature in the process , extended to the intentional infliction of emotional distress. In that judgment, actual malice was defined as

"Knowledge that the statement was false or with reckless disregard to its truth or falsity."

"Knowing that the utterance is wrong or that it ruthlessly neglects the fact whether it is true or false."

Usually the first amendment is used only to prevent direct government censorship . Despite protection from these government-initiated defamation processes, it is recognized that it is necessary to authorize the state to conduct a defamation process between private individuals. The scrutiny of defamation trials carried out by the Supreme Court is therefore sometimes viewed as part of a broader development in US jurisprudence: away from the strict legal requirements for trials towards the application of the principles of the First Amendment when private individuals appeal to state power.

The Noerr-Pennington Doctrine is also a legal guideline that often prevents the application of antitrust law to statements made by competitors in public institutions: a monopoly can go unhindered to the city council and insist that his competitor does not have a building permit is granted without being subject to the Sherman Antitrust Act . This principle is also applied outside of antitrust law in the processes, the content of which is a violation of the state in the international influencing of company connections and SLAPP processes (processes started by large companies in which they burden their less powerful opponents with such high defense costs that they criticize them stop) are.

Similarly, some states, under their protection of free speech, have adopted the Pruneyard Doctrine, which prevents private owners who own a common public forum (often a mall or grocery store) from using their private property rights to political speakers and signature collectors from theirs Keep property away. This doctrine was rejected as a federal law in the United States, but is increasingly accepted as a state law.

Political speeches

US federal election campaigning law of 1971 and similar laws limited the amount of money that could be donated to political campaigns and the expenses of candidates. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the 1976 Act in the Buckley v. Valeo apart. The court upheld some parts of the law but rejected others. He realized:

"[T] he ceilings imposed [on campaign contributions] […] serve the basic governmental interest in safeguarding the integrity of the electoral process without directly impinging upon the rights of individual citizens and candidates to engage in political debate and discussion."

“[T] he limits on [donations to political parties] [...] serve the essential interests of the government in ensuring the integrity of the electoral process without affecting the rights of individual citizens or candidates to participate in political debates and discussions to hurt."

At the same time, the Court lifted the limits on the candidates' spending, which it believed

"[Imposed] substantial restraints on the quantity of political speech."

"Significantly reduced the number of political speeches."

Additional rules on campaign funding were adopted by the Supreme Court in 2003 in the McConnel v. Federal Election Commission scrutinized. The case revolved around the 2002 bipartite campaign reform law, a law that introduced several new limits on campaign funding. The Court upheld the rules on the procurement of soft money , money that is not donated to the election campaign but used directly to support it, by national parties and the use of soft money by private organizations to help certain members of the electorate Funding advertisements prohibited. At the same time, the Court raised the issue selection policy ( English choice of expenditure rule on), said that the parties either their spending could coordinate for all candidates or it could allow the candidates to spend independently money for the campaign, but not a mix of these two approaches are allowed to apply. The Supreme Court also stated:

"[The] provision place [d] an unconstitutional burden on the parties' right to make unlimited independent expenditures."

"[The] regulation imposes an unconstitutional burden on the party's right to spend unlimited, independent amounts of money."

He also ruled that another directive banning minors from making political contributions was unconstitutional, with the Court relying on the Tinker case, a precedent .

Shortly after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 , in the course of George W. Bush's security campaign, so-called free speech zones (“areas of free speech”) emerged. They were set up by the Secret Service , a US law enforcement agency responsible, among other things, for the protection of the president, near the places where Bush passed or where he gave a speech. Before and during the event, officials looked for people with anti-Bush signs (sometimes people with pro-Bush signs) and directed them to the free speech zones . Local officials often prohibited reporters from filming or speaking to protesters. Protesters who refused to enter the free speech zones were often arrested and charged with trespassing , disturbing the peace and resisting state violence. In 2003, the rarely used federal law was US Code Title 18.1752 argued that says that "entering a restricted area around the President of the United States" ( english entering a restricted area around the President of the United States ) an offense is.

Involuntary briefing

A minority questioned whether laws on involuntary admission, when the diagnosis of the mental illness leading to full or partial admission is made to some extent on the basis of language or on the documents written by the admitted person, the right to freedom of speech hurt that person.

The effects of the first amendment on involuntary, psychiatric , drug treatment were also questioned. The competent district court was in 1982 in the case of Mills v. Rogers' opinion:

"[W] have powers the Constitution has granted our government, involuntary mind control is not one of them."

"[E] gal what our government is authorized by the constitution, it is not authorized to involuntary mind control."

However, that ruling did not set a precedent and the subsequent decision of the Supreme Court was essentially inconclusive.

Freedom of the press

See also freedom of expression

The press freedom , as freedom of speech, affected by restrictions on the basis of libel laws. However, these restrictions have been declared unconstitutional if they were aimed at the political message or the content of newspapers.

In the case of Branzburg v. Hayes of 1972 restricted the Supreme Court the ability of the press, of a subpoena by a grand jury , citing freedom of the press not to be followed. Was the subject of the process, whether a reporter could refuse, "to appear before the grand juries of the state and throughout the US and testify as a witness" ( english [to] appear and testify before state and Federal grand juries ) when it afterwards, occupations that such a publication and such testimony "the speech and press freedom, which is guaranteed by the first Amendment, reduced" ( English abridges the freedom of speech and press guaranteed by the first Amendment. ). The judges decided with five votes in favor to four against that the first amendment to the constitution did not grant such protection.

Taxation of the press

State governments have the right to tax newspapers just as they can tax other commercial goods. In general, taxes that only affected newspapers have been declared unconstitutional. In 1936 , in the Grosjean v. American Press Co. will void a tax imposed by the United States government on newspaper advertising income. Some taxes that favored the press were also suspended. So who told Supreme Court , for example, in 1987 an Act of Arkansas , religious, professional, trade and sports magazines ( English religious, professional, trade and sports journals ) are exempt from taxation, to be invalid because the law certain newspaper content preferentially treated.

In the case of Leathers v. Medlock of 1991 , the Court ruled that states different media should be treated differently by about the cable television but taxed, which newspapers do not. The Court found:

"Differential taxation of speakers, even members of the press, does not implicate the First Amendment unless the tax is directed at, or presents the danger of suppressing, particular ideas."

"Different taxation of speakers, even members of the press, does not fall under the first amendment to the constitution if the tax does not target certain ideas or runs the risk of suppressing them."

Regulation of the content

The courts have shown little sympathy for the regulation of the press in terms of content. 1971 declared Supreme Court in the process Miami Herald Pub. Co. v. Tornillo, a state law that forced newspapers criticizing politicians to publish their responses, unanimously invalid. The state claimed that the law was passed to ensure press liability. Finding that only freedom of the press, not press liability, is set out in the First Amendment, the Supreme Court ruled that the government should not force newspapers to publish anything they refused to publish.

However, the regulation of the content broadcast by television or radio has been upheld by the Court in various processes. Because there are only a limited number of frequencies available for non-cable television and radio, the government licenses various companies to use these frequencies. However, the Supreme Court ruled that this lack of spectrum problem does not allow a trial on the First Amendment to begin. The government can prevent radio and television broadcasters from broadcasting, but not because of their content.

Freedom of assembly and the right to petition

The right to petition the government has been interpreted by the courts to mean that it applies to petitions to all three branches : Congress, the executive and the judiciary . The Supreme Court interpreted the phrase "redress of grievances" ( English redress of grievances ) generous: it is possible for example to ask the Government to use its power to promote the common good. However, the right to petition has been restricted directly by Congress several times. In the 1790s , Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts (see above), which punished opponents of the Federalist Party ; the Supreme Court never questioned the constitutionality of the law . In 1835 , the House of Representatives passed the Gag Rule , which banned petitions calling for the end of slavery . The gag rule was never the subject of any trial in the Supreme Court , but was repealed in 1840 . During the First World War , some individuals were punished for calling for the Sedition and Espionage Acts (see above) to be withdrawn ; again, there was no trial before the Supreme Court about these convictions.

The freedom of assembly was originally closely connected with the right to petition. A significant case involving the two rights was the United States v. Cruikshank from 1876 . At that time the Supreme Court ruled :

"[People have the right] peaceably to assemble for the purpose of petitioning Congress for a redress of grievances."

"[People have the right] to gather peacefully to petition Congress to put an end to grievances."

In essence, it was stated that freedom of assembly was secondary and the right to petition was primary. However, in later trials the meaning of the word freedom of assembly was expanded. In 1939 , for example, the Hague v. CIO "replace [at] views on national questions" on the right to gather, ( english [for the] communication of views on national questions ) and "[in order] to disseminate information" ( English [for] Disseminating information ).

International significance

Most of the provisions of the United States Bill of Rights are based on the English Bill of Rights of 1689 and other aspects of British law. However, many of the rights granted by the First Amendment to the US Constitution are not contained in the UK Bill of Rights . Thus, the First Amendment guarantees, for example, freedom of speech for all the people, while the English Bill of Rights (only "[the] freedom of speeches and debates and other operations in parliament" English freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament. Granted). The Declaration of Human and Civil Rights , a document that was passed in the wake of the French Revolution just weeks before the US Congress proposed the Bill of Rights , contains certain freedoms similar to those of the First Amendment. For example, it states:

"Tout citoyen peut donc parler, écrire, imprimer librement"

"Accordingly, every citizen can speak, write and print freely."

Freedom of speech is wider in the United States than in almost any other nation. While the first amendment does not specifically limit freedom of speech, other legal declarations sometimes do. The European Convention on Human Rights allows for example restrictions on freedom of speech

“Necessary for national security, territorial integrity or public security, for maintaining order or preventing crime, for protecting health or morals, for protecting the good reputation or the rights of others, for preventing the spread of confidential information Information or to maintain the authority and impartiality of the judiciary. "

In practice, these loopholes have been interpreted fairly generously by European courts.

The first amendment to the constitution was one of the first guarantees of religious freedom : neither the English Bill of Rights nor the French declaration of human and civil rights contains a corresponding clause. Due to the content of the first amendment to the constitution, the USA is neither a theocracy like Iran , nor an officially atheist state like the People's Republic of China .

Web links

- Kilman, Johnny and George Costello (Eds). (2000). The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation.

- Peter Irons: A People's History of the Supreme Court. Penguin, New York NY u. a. 1999, ISBN 0-670-87006-4 .

- Krusch, Barry (2003). Would The Real First Amendment Please Stand Up? This page, with an emphasis on the 1st Amendment to the US Constitution, examines the analytical process by which the Supreme Court interpreted the US Constitution and supports the theory that this process led to the emergence of a "virtual First Amendment".

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gitlow v. New York , 268 US 652 (1925).

- ↑ Global Ethic Foundation: German translation .

- ↑ Scientific Services of the German Bundestag - Department III: Constitution and Administration: The question of a reference to God in the US Constitution and the case law of the Supreme Court on the separation of state and religion (registration number: WF III - 100/04) . German Bundestag. May 13, 2004. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States: McConnell v. Federal Election Commission, 540 US 93 (2003), slip opinion . Supreme Court of the United States. December 10, 2003. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ↑ http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/html/uscode18/usc_sec_18_00001752----000-.html