Ahrensburg Castle

The Schloss Ahrensburg is located in the directory named after the castle district town of Ahrensburg in southern Schleswig-Holstein , about 30 kilometers north-east of Hamburg city center. The small moated castle is actually a mansion and as such was once the center of a noble estate . However , the building has been referred to as a castle since the 18th century.

The castle is one of the main works of Renaissance architecture in Schleswig-Holstein. It is one of the most famous sights in the state and is open to the public. In addition to the manor house, the palace area includes the former manor chapel with its so-called God's booths and a palace park designed in the style of English landscaped gardens.

use

The Renaissance building , originally protected by simple fortifications , has been in the possession of various lines of the Rantzau family, which belonged to the Holstein nobility , since the 16th century . After a period of economic decline, the Ahrensburg estate and castle came into the possession of the Schimmelmann family , who had been raised to the nobility , and under whom the manor house was transformed into an elaborate country residence. The Schimmelmanns stayed in Ahrensburg for several generations, then the property was sold in 1932. After the castle had served various purposes during the Second World War , it now houses a museum focusing on Schleswig-Holstein's aristocratic culture. Weddings through the registry office in Ahrensburg are possible on the ground floor in the garden hall or on the second floor in the Louis Seize salon or in the library.

history

From Arnesvelde Castle to Ahrensburger Gut

In the vicinity of today's castle there was already a fortified manor house in the Middle Ages , the so-called Arnesvelde Castle , which belonged to the Counts of Schauenburg . In 1327 the complex and the adjoining lands came to the Reinfeld monastery , where it remained for the next centuries. The little castle was hardly used and over time it began to deteriorate. In the course of the Reformation , the monastery was secularized in the 16th century and Arnesvelde became the property of the Danish King Frederick II . He initially awarded it to the Blome family in 1564.

On March 9, 1567, the general Daniel Rantzau , who was in royal Danish service, received the remains of the castle as a reward for his services and compensation for debts the king had with him. Together with the castle he received the four villages of Woldenhorn, Ahrensfelde, Meilsdorf and Bünningstedt. Rantzau, who came from the Nienhof branch of the most influential family in Schleswig-Holstein at the time, fell two years later in a battle for the Swedish fortress of Varberg without ever having set foot in his new property. Since he was childless, the inheritance fell to his brother Peter Rantzau , who established an extensive estate with the land.

16th to 18th century: A mansion of the Rantzau family

Peter Rantzau took over the land around the future castle in 1569. North of the village of Woldenhorn - which has merged into today's city of Ahrensburg - a large estate was built, which became the economic center of the complex. Peter Rantzau had the manor house built between the manor buildings and the village in the south, in a flat brook valley through which the Hunnau flows. For the building, which was built around 1585, the remains of the Arnesvelder Castle located a few kilometers to the south were demolished and some of the material was used in Ahrensburg; only a few overgrown ramparts and moats are left of the medieval castle. The name of the castle carried over to the new property. Peter Rantzau's cousin from the Breitenburg line of the family, the humanist Heinrich Rantzau , summed up the change of location of the building in poetic words:

“See me castle, which in future will live in the mouth of the time,

Arnsburg is named with a fitting name, I

lay lonely and my modern stone went in ruins.

Now I am in a nicer place again. "

The mansion was built in the traditional form of the so-called multiple house and equipped as a modern, lavish Renaissance seat. Heinrich Rantzau described the manor house and its furnishings in 1597 - probably a bit exaggerated - as "a building built at inconceivable costs, the rooms of which were clad in gold and silver" . The manor house was to serve Peter Rantzau primarily as a retirement home and, according to his will, then "for eternity" as the ancestral home of his family branch. With the castle chapel, completed in 1596, in the immediate vicinity of the estate, he also created the burial place for himself and his descendants. However, the dream of permanent fame of his line already ended in the following generation, as his son Daniel died without male offspring. Nevertheless, the estate remained in the possession of the widely ramified Rantzaus, and the manor house housed a total of seven generations of the family until the 18th century.

An initial phase of the estate's economic upswing also found expression in the Gottesbuden at the castle church, a pension facility for old and disabled estate workers founded by Peter Rantzau. In contrast to the Breitenburg members of the Rantzau family, who provided several royal governors and thus were actively involved in state politics, the Ahrensburg lords remained rather insignificant in the history of the duchies. During this time, the mansion was primarily the elaborate residential building of a noble estate and less a place of princely court culture.

From the 17th century, the Ahrensburg property went through several financial crises, also triggered by the consequences of the Thirty Years' War . In the 18th century, the Rantzaus also got into conflicts with their farm workers, who were serfs in their status , but whose demands for better living conditions grew increasingly and culminated in protracted uprisings. This period of conflicts between serfs and landlords is sometimes referred to in local literature as the Thirty Years Ahrensburg Peasants' War . The estate experienced a final economic boom after it was passed on to Detlev Rantzau from the Putlos line of the family through inheritance and marriage . When Detlev Rantzau died in 1746, the heavily indebted property could no longer be held by the family and was offered for sale in the middle of the 18th century.

18th to 20th century: The summer residence of the Schimmelmann family

After he had been in negotiations with the last estate manager Christian Rantzau since January 1759, the merchant Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann , who came from Western Pomerania, bought the highly indebted estate in May of that year for 180,000 Reichstaler . In 1756, during the Seven Years' War, Schimmelmann was promoted to grain supplier for the Prussian army and, thanks to fortunate circumstances, was able to acquire the inventory of the Meissen porcelain factory . With the white gold - part of the porcelain is still on display in the castle today - he acquired part of his considerable fortune. Schimmelmann took part in the Atlantic triangular trade as a slave trader and soon became one of the richest men of his time. His skills as a financier led him to the Danish court, where he was appointed royal treasurer in 1768. Copenhagen became his main residence, where he acquired the so-called Berkenthische Palais near the Amalienborg Palais' , today's Odd Fellow Palæet . His business also took him to Hamburg and Altona, which was then administered by Denmark . In Hamburg, he acquired the Gottorper Palais near the Michaelis Church as a city domicile. Ahrensburg, on the other hand, was to serve him as a country residence near the cities of Hamburg and Altona, as well as the manor house in Wandsbek, which was also acquired .

Schimmelmann had the Ahrensburg manor house converted into a late baroque country palace, which was his summer residence until the new building in Wandsbek was completed in 1778. The Schimmelmann family usually left Copenhagen in May of each year and stayed in Ahrensburg until November, where they were cared for by an average of twenty-five domestic workers. The Schimmelmann, who came from the middle class, was raised to baron and finally to count and married his children into the Holstein-Danish landed gentry. The manor house developed into a social center of the Holstein manor culture and the Danish King Christian VII also visited it several times. The building experienced its heyday in this era and Schimmelmann wrote about his country estate "I have so much love for Ahrensburg [...] it is my only pleasure" .

With the completion of the new Wandsbeker Castle in 1778, Ahrensburg was visited less often. After the treasurer's death, the children divided the inheritance, which included six mansions and palaces. The Ahrensburg estate went to the son Friedrich Joseph Schimmelmann. Under him, the most progressive innovation, serfdom was abolished in 1788, but since he was unable to continue his father's successful business, he increasingly indebted the property. At the beginning of the 19th century, the economic crisis deepened due to the consequences of the Napoleonic Wars , which affected neighboring Hamburg as well as the Danish kingdom. The stagnation did not end until the middle of the century and the various Schimmelmann possessions came together again in one person under Ernst Schimmelmann , a great-grandson of the treasurer. During this time the manor house was modernized and the old farmyard on the castle island was demolished; new outbuildings were erected east of the mill pond. The farm, supplemented with successful horse breeding, continued until the beginning of the 20th century.

With the end of the First World War , the estate experienced one last major crisis. The old form of manor rule was outdated, the depression of the 1920s and the subsequent global economic crisis led to renewed over-indebtedness, which resulted in the sale of the estate and the manor house. Up to 1932, a total of seven generations of the Schimmelmann family lived in the castle, just as many as at the time of the Rantzau family.

From the 20th century to the present

The estate's lands were sold to various buyers, but interest in the old mansion was low, so that it was empty from 1932. Some of the inventory was auctioned off as early as 1927, and in 1929 the local savings bank bought the remaining items for 25,000 Reichsmarks . On the initiative of a citizen of Ahrensburg, the local savings bank also bought the castle, which had been open to visitors since 1932, and set up the first museum in 1935. In 1938 a castle association was founded with the aim of preserving the manor house. In the course of the Second World War, the museum was closed in 1941, the inventory was relocated and the castle was hidden under camouflage nets. During the war - which it survived largely unscathed - it served, among other things, as a military hospital in 1943 and as the headquarters of the German Naval Observatory in 1944 . After the end of the war, the castle briefly housed a command post for the British Army, after which it took in more than 400 refugees. In 1947 a vocational school moved in, which remained until 1954.

The Schlossverein under the direction of Hans Schadendorff tried to reopen the museum in the post-war period , which happened in 1955. In the decades that followed, the palace complex was renovated in stages, especially from 1984 to 1986 under the direction of Horst von Bassewitz . It served, among other things, as a backdrop for the German Edgar Wallace films The Green Archer and The Strange Countess . Some exterior shots of The Dead Eyes of London were made at the Castle Church. The castle was also the location of the ARD fairy tale film adaptation of The Brave Little Tailor .

On February 21, 2003 the castle was incorporated into a foundation under civil law established by the state of Schleswig-Holstein, the Stormarn district, the city of Ahrensburg and the Sparkasse Stormarn . According to its own statements, the foundation receives decreasing amounts of public funding, a good two thirds of the total budget required by the house is generated by itself. From 2002 to 2006 the foundation received an annual grant of 25,600 euros from the state budget. The 2015 and 2016 annual reports can be viewed on the castle's website under the heading "Foundation".

The maintenance of the building is financed, among other things, by the entrance fees to the museum, which is open all year round, and up to 30,000 visitors are counted annually. Further income results from the diverse usage concept of the palace complex, regular festivities and concerts are held. Some of the castle rooms can also be rented for events; By renting out the wedding room, for example, up to 40,000 euros can be earned annually. A large children's program with over 250 events a year should also inspire the younger generation for the castle. From 2009 to 2016, a total of four construction measures with a total volume of 2.6 million euros were invested in the complete renovation of the house thanks to public funding. During the same period, also with public funds, the moat was cleared and the park was renovated. The house receives donations from donations and private initiatives of the Freundeskreis Schloss Ahrensburg e. V. , which was able to provide over 300,000 euros for renovation work and purchases in recent years. Further support comes from the Sparkassen-Stiftung Schloss Ahrensburg , which has assets of 400,000 euros (as of the end of 2016) and which works closely with the Schloss Ahrensburg Foundation .

Castle building

Originally, only the buildings of the sovereigns, i.e. the king or the appointed dukes in Schleswig and Holstein, had the privilege of being called a castle. However, this custom was broken, depending on the status and influence of the client concerned. Even Christian Rantzau , the governor of the Danish king was, in 1651 the chapel of his Breitenburg attach an inscription in which the mansion was determined local to the castle. The Ahrensburg manor house has also been referred to as a castle since the 18th century due to its importance and its art-historical position in Schleswig-Holstein.

Building description

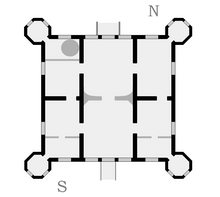

The castle stands on a castle island surrounded by the Hunnau and is surrounded by a moat. The building was built towards the end of the 16th century and construction work was completed around 1585. The builder of the Ahrensburg Palace is unknown. For the manor house, building material from the demolished Arnesveld Castle was partly used. The structure including the basement is almost cube-shaped with a base area of approximately 18 by 20 meters. The three white long houses lying next to each other are typical of the Holstein manor architecture and were to be found in a similar design in many systems of the time. The gables of the houses are curved and adorned with small obelisks , the windows that break through the building symmetrically were once provided with decorative frames and window crosses made of sandstone.

The cube is flanked by four slender octagonal towers. These towers were not included in the first draft of the house and were only added to the manor during the construction phase. They have copper-covered domes, which contrasts with the with red bricks form roofs of longhouses. The wind flags of the towers, each in the form of half a horse and a rider, are reminiscent of the author of the estate, Daniel Rantzau, who is said to have been killed by a cannonball together with his horse in the Battle of Varberg.

Stylistic classification

Various art historians describe the manor house as one of the most mature achievements of Renaissance architecture in the duchies. The castle combines stylistic references to the Dutch Renaissance with the traditional, local forms of construction in Schleswig-Holstein. It is one of the few houses of the time in the country that, apart from the white whitewash and details on the facades, has remained almost unchanged in the exterior. The castle was originally without white plaster; the red brick facades and the window openings were structured by sandstone elements. Once similarly important buildings of the epoch, such as the manor house at Gut Rantzau or the Wandsbeker Castle, were largely redesigned or later even demolished during the Baroque period, while other Renaissance buildings, such as the manor house on Nütschau , were far more rustic.

The traditional twin house of Schleswig-Holstein culminated in an artistically perfect form in the Ahrensburg Castle . While the two-fold semi-detached houses had been widespread as residential buildings on the regional moated castles since the Middle Ages, three-fold or even multi-tiered houses did not gain acceptance until the 16th century. They were not always planned in one move like Ahrensburg, but rather, like the Ehlerstorf manor house, only expanded when necessary. Up until then, the towers of the buildings primarily served a functional purpose. Older semi-detached houses were often without, others like Breitenburg or Wahlstorf only had a stair tower, and the original Kiel Castle had two stair towers. The Glücksburg Castle , the sovereign counterpart to the Ahrensburg building, was the first multiple house to be equipped with four striking corner towers, which were also intended from the outset as residential pavilions and not as stair towers.

The symmetry of Glücksburg is repeated in Ahrensburg. The similarity between the two buildings is obvious, but the Glücksburg Castle, which is a good third larger in terms of its basic dimensions, consists of simpler structures; the longhouses are the same size, and the massive towers only slightly protrude from the eaves . The smaller mansion, on the other hand, has more balanced proportions . While the building looks like a cube of three similar houses at first glance, it is only at second glance that it becomes apparent that the houses on the side are slightly narrower than the central nave, which makes the facades appear less severe. The slender corner towers tower over the otherwise three-story building with a fourth floor and are crowned with tall, lantern-like domes. The influence of the Dutch Renaissance can be found in the curved gables with their decorations as well as in the curved domes of the towers.

Ahrensburg is considered to be the last significant creation of the so-called golden age of Ranzau , an era in which more than seventy Schleswig-Holstein goods were in the possession of the ancient noble family. The construction of the double house reached its climax with the completion of the Ahrensburg Castle. Subsequent Renaissance mansions of this type, as they were built in the 17th century on Gut Wensin or on Gut Jersbek , were again simpler. The traditional multiple houses were finally replaced by the more modern baroque facilities of the 18th century, as can be found on Gut Güldenstein or Gut Pronstorf .

18th century remodeling

After Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann had acquired the estate, the complex, which had been dominated by the Renaissance up until then, was rebuilt from 1759 onwards. Schimmelmann had extensive drafts for a conversion of the palace, its outbuildings and gardens made, but the plans were only implemented on a smaller scale.

The castle was to be redesigned in the form of a baroque palace. Similar to the renovation of the Kiel Castle under Ernst Georg Sonnin , the effect of the structure of the Ahrensburg mansion, consisting of long houses with single roofs, was to be completely changed by a large, uniform mansard roof and the removal of the Renaissance gable. In the end, however, Schimmelmann only decided to make minor modifications; he even had the old gables rebuilt in their original form. The house ditch was filled in in 1759, the brick façades, which had been red until then, were whitewashed and the sandstone frames of the windows were removed. In contrast, major changes were made to the interior of the castle.

inside rooms

The manor house has four floors: the basement, which is partly below the waterline, extends in height to the edge of the house ditch; the lower residential floor with the entrance area of the castle is approximately at the level of the surrounding area, above are the middle and top floors, followed by the three parallel attics.

Following the external structure, the castle is also divided into three parts inside. The original floor plan extends through all four floors and was similar to that of Glücksburg, albeit in a reduced version. As there, the middle house housed halls leading through the entire building, while the side houses were each divided into two halves by a central wall. In the western nave there was originally an internal spiral staircase, which was later removed. There are three more spiral staircases in the towers, which, like in Glücksburg, initially contained small, octagonal cabinets .

After Carl Heinrich Schimmelmann took over the castle in the 18th century, he had the interior of the building completely redesigned, so hardly anything has been preserved from the Renaissance furnishings of the house. The continuous entrance hall was divided into two halves from 1760, and the salons in the side houses were also partly separated by partition walls. The rooms were newly decorated in the Rococo style and a large, open staircase was set up, which was broken through the floors in the right nave. The castle could now be entered at ground level from the garden through the filled-in moat, so that a second portal was built into the south facade next to the northern main entrance. Under the successors of Schimmelmann, the castle was refurbished again in the 19th century. Some of the interiors were decorated in the classicism style and the great knight's hall on the middle floor was divided into two smaller halls.

tour

The castle museum allows you to visit the lower and middle floors of the manor house. The basement rooms are rented out by the foundation for private events, the second floor is open on weekends. The sequence of rooms to be visited, in which a large part of the historical inventory is collected, all date from the Schimmelmann era. Some of the furniture came from regional manufacturers, and some were acquired on extended trips of the family members in Italy. Since the castle serves as a museum of Schleswig-Holstein's aristocratic culture, furniture and paintings from other mansions in the country can also be found there. The preserved works of art from the original furnishings include animal still lifes by Tobias Stranover, landscape paintings by Philipp Hackert and wallpapers painted by Giuseppe Anselmo Pellicia in the classical antiquity.

The building is entered via a stone bridge on the north side of the castle, which leads directly into the simple vestibule on the lower floor. To the east of this is the dining room, paneled in dark oak, the panels of which come from a Parisian factory . The panels, made in the second half of the 18th century, still have the assembly instructions of French artisans on their backs. A smaller salon leads to the garden room, which is decorated with large flower still lifes and is connected to the outside area by a small bridge. The museum tour leads through another salon around the vestibule and into the large stairwell.

The actual staircase is a free-standing baroque construction made of oak that leads to the upper floors. On the middle floor, next to the former bedrooms and living rooms of the count's family, there are two large halls, which have taken the place of the former knight's hall since the mid-19th century. With its large-format portraits, the so-called Emkendorf Hall refers to the family connection to the manor house of the same name near Kiel . The second large room on the middle floor follows the Emkendorf hall, the ballroom with a star-shaped parquet floor , the current furnishings of which date from 1855. The top floor of the palace contains the library and the so-called Louis-seize room, two rooms that cannot be seen during regular museum operations, and there are also three rooms for the children's program. Further rooms are used by the castle administration.

Surroundings of the castle

Castle island and garden

The castle protrudes directly from a house moat that was created together with the building in the 16th century. Although such trenches had hardly any fortification use since the end of the Middle Ages , they were retained as a means of expressing strength and dignity in many Schleswig-Holstein manors. When Schimmelmann took over the castle in the middle of the 18th century, the moat with its apparent defensive strength no longer corresponded to the taste of the time and was filled in, the building could be entered directly and without bridges for the first time. In the course of the next few centuries, however, this measure led to increasing moisture penetration of the basement, as the ditch in the marshy Au valley also served as a kind of drainage . The moat was reconstructed from 1983 to 1985 and the castle has been surrounded by water twice since then.

The castle is located in the southern area of the rectangular castle island. This was originally partially fortified with its ditch fed by the Hunnau, a tributary of the Alster , and a surrounding wall. The elongated castle pond formed to the east from the widened ditch served as a reservoir for the operation of a water mill, which was once part of the estate management. The castle pond is now leased by the Anglerverein Ahrensburg from 1958. V. Various outbuildings stood on the northern part of the island until the middle of the 19th century. The buildings of this farm yard were partly demolished under Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann as part of the planned redesign of the palace complex. Instead, Georg Greggenhofer designed a large gatehouse, which was to serve as a combined cavalier's house and farm building. The U-shaped complex would have been designed in a similar way to Greggenhofer's gatehouse at Gut Hasselburg and would have encompassed the castle and exceeded it in terms of area several times. However, the baroque building never got beyond the planning stage, just like a design by Carl Gottlob Horn from 1766, which would have connected the palace on the courtyard side with two winged buildings with quarter-circle walls.

The palace garden, which was located outside the palace grounds on the site of today's Marstall and primarily served as a kitchen garden, would have been transformed into a large baroque park according to Greggenhofer's plan . The design envisaged providing the garden in front of the manor house with large broderie parterres and dividing its western area outside the castle island with nine bosquets . Several pavilions were planned at the intersection of long lines of sight . This extensive redesign, however, was not tackled and Schimmelmann concentrated instead on creating a representative park at Wandsbeker Castle. The baroque gardens on the Ahrensburg Castle Island were realized on a smaller scale by Carl Gottlob Horn. Only the linden tree avenues of the castle island as well as two sandstone vases and two lions flanking the castle bridge have been preserved from this park. The small palace park as it is today was designed in the 19th century in the style of English landscape gardens . The area was also topographically reshaped and given a slightly hilly character. The paths in the Hunnau meadow valley outside the island lead to the somewhat distant chapel with its holy booths.

Castle church and God's booths

The Ahrensburg Castle Church is within sight of the manor house . The church was built between 1594 and 1596 under Peter Rantzau as an estate chapel and tomb and was dedicated to its patron saint , the holy apostle Peter . It replaced a smaller previous building on the local cemetery. Originally called Woldenhorn Church, the building has only been called the Castle Church since the 19th century. The church now serves as the Evangelical Lutheran parish church of the city of Ahrensburg.

The simple hall consists of a cuboid structure, on the north side of which is a small burial chapel, which was added under Detlev Rantzau in the 18th century. On the west facade there is a low tower, which was built under Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann in place of a free-standing belfry. The tower was crowned with a copper helmet until 1804, then this was replaced by the still existing blunt tent roof. The roof turret sitting on the roof ridge served as an eye-catcher for the line of sight through the Woldenhorn settlement beginning behind the church. In contrast to the “modern” Renaissance mansion at the time, the church was still shaped by the forms of the brick Gothic, which can still be seen in the pointed arched windows. The flat ceiling with the fan vault and the stars imitating the sky is unique in this form in Schleswig-Holstein. Only a few pieces of the original furnishings of the church have survived, the present baroque inventory of the church comes mainly from the first half of the 18th century and was commissioned by Detlev Rantzau. Left and right of the high altar are the patron saints' boxes of the Ahrensburg landlords, several tombs of the Rantzau family have been preserved in the chapel annex.

In 1639 under Kay Rantzaus, an organ gallery was built to accommodate a two-manual organ by the organ builder Friedrich Stellwagen (1603–1660).

To the north and south of the church are the so-called God's booths . They are two elongated, one-story residential buildings that frame the former churchyard and originally formed an enclosed area with walls in the east and west. The houses contained apartments for needy members of the estate, the elderly and the sick, for whom the landlord felt responsible, a novelty at that time and despite the existing duty of care of the landlords towards their serfs, not a matter of course on all estates. In his will, Peter Rantzau decreed that the foundation for the poor should continue to exist even after his death and even announced “God's punishment and all misfortune here on earth” to those who would enrich themselves or neglect the foundation.

The historic buildings were erected at the same time as the church at the instigation of Peter Rantzau and contain eleven - previously twelve - apartments consisting of a kitchen and a living room, which have been inhabited for over 400 years and are still used for social purposes. The rooms managed by the parish are rented out to the present for a symbolic fee.

The former farmyard and the stables

Until the middle of the 19th century, some of the outbuildings belonging to the estate were still on the castle island. Under Ernst Schimmelmann, these buildings were demolished from 1856 and instead the island's gardens were expanded to the north. The buildings to the east of the palace on the site of the old palace gardens and earlier outbuildings were replaced by new buildings.

The entrance area of the castle island was provided with a granite arch bridge from 1841 to 1843 and a neo-Gothic gatehouse in 1845 , which had to be demolished in 1960 due to its disrepair. Opposite is the Marstall , built from 1846 onwards , which is the only significant building of this construction phase that has been preserved. It has served as the cultural center of the city of Ahrensburg since 2000. The large structure in the arched style was built in 1845 and housed not only stables, but also official apartments for employees of the estate. Behind the three-winged building, the farm yard was renewed and provided with cattle stalls, granaries, a riding arena and greenhouses. In 1896 a fire destroyed most of the buildings. Some of the new buildings that were built afterwards are still preserved, but the former farmyard was no longer needed after the farm was closed and became private property.

To the west of the castle island was the so-called Bagatelle , once a meierhof of the estate. The wash house there from Schimmelmann's time has been preserved and has been used by the local citizens' association since a complete, partly voluntary renovation in 2005.

The planned city of the 18th century

The extensions to the palace complex, commissioned by Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann, were only implemented to a limited extent, but the plans also concerned the village of Woldenhorn, upstream of the estate. According to Schimmelmann's will, the place was to be redesigned into a small ideal town , which was implemented by 1766 by demolishing the old town center and the subsequent new building. The plans for this project probably came from the Ludwigsluster master builder Johann Joachim Busch . The roof turret of the castle church served as a point de vue of a visual axis that leads from there over the old market square and a meadow to the south, where three radial streets designed as avenues on the so-called Rondeel open up the wider area. The ideal city of Woldenhorn was the only planned foundation in Schleswig-Holstein in the 18th century.

The construction of the small settlement followed the hierarchy of social classes at the time. Below the castle church, within sight of the manor house, were the houses of the estate officials, followed by those of the merchants and then the houses and farms of the farmers. In addition to the local farmers, craftsmen and tradespeople were settled following the Ludwigslust model, who were supposed to help the estate area to regain economic growth. However, Schimmelmann's great plans could not be realized and so Woldenhorn initially remained a relatively insignificant place, which was renamed Ahrensburg in 1867 and made a town in 1949.

Little remains of the 18th century buildings in Ahrensburg / Woldenhorn. The radial roads were cut through in the 19th century by the railway line and in the 20th century by a modern traffic system, many of the old houses were demolished in the post-war period and replaced by functional buildings. However, the rectangular meadow continues to form the center of the town, and the structure of the baroque complex can still be seen from the air.

reception

The children's radio play series Schubiduuu ... uh by Peter Riesenburg and Hans-Joachim Herrwald is about a ghost who lives in Ahrensburg Castle.

literature

- Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg 1715-1867. Wachholtz, Neumünster 2006, ISBN 978-3-529-07128-7 (= Stormarner Hefte 23; review ).

- Georg Dehio : Handbook of the German art monuments . Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 978-3-422-03033-6 , pp. 136-139.

- Johannes Habich , Deert Lafrenz, Heiko KL Schulze, Lutz Wilde: Castles and manors in Schleswig-Holstein. L&H Verlag, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 978-3-928119-24-5 , pp. 200-207.

- Peter Hirschfeld: Mansions and castles in Schleswig-Holstein. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1980, ISBN 978-3-422-00712-3 .

- Kurt Janssen (Ed.), H. Schadendorff: Ahrensburg - Castle and Church. Graphische Kunst- und Verlagsanstalt Gries, Ahrensburg 1967.

- Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle. Wachholtz, Neumünster 2007, ISBN 978-3-529-07211-6 .

- Frauke Lühning, Hans Schadendorff: Ahrensburg Castle. Wachholtz, Neumünster 1982, ISBN 3-529-02828-2 .

- Deert Lafrenz: manors and manors in Schleswig-Holstein. Published by the State Office for Monument Preservation Schleswig-Holstein, 2015, Michael Imhof Verlag Petersberg, 2nd edition, ISBN 978-3-86568-971-9 , p. 32.

Web links

- Ahrensburg Castle

- Marstall Ahrensburg cultural center

- The history of the Ahrensburg estate ( Memento from December 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- Material on Ahrensburg Castle in the Duncker Collection of the Central and State Library Berlin (PDF; 262 kB)

- Ahrensburg Castle as a 3D model in SketchUp's 3D warehouse

Individual evidence

- ↑ In Schleswig-Holstein (and Mecklenburg) the designation castle was reserved for sovereign or episcopal seats.

- ^ Ahrensburg Castle Foundation: Getting married in a fairytale castle. (Leaflet 09/2016).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , p. 136.

- ↑ a b Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 17.

- ↑ The time of the Rantzau in Ahrensburg; Webpage of the "Historical Working Group Ahrensburg" ( Memento from December 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c schloss-ahrensburg.de - overview of the history of the castle , accessed on December 6, 2009.

- ↑ a b c d Frauke Lühning: Schloss Ahrensburg , p. 10.

- ^ Frauke Lühning, Hans Schadendorff: Schloss Ahrensburg . 3. Edition. Wachholtz, Neumünster 1991, ISBN 3-529-02950-5 (= Guide to Schleswig-Holstein museums. Volume 1. ), p. 6.

- ↑ a b Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 7.

- ↑ Habich, D. Lafrenz, H. Schulze, L. Wilde: Schlösser und Gutsanlagen in Schleswig-Holstein , p. 201.

- ↑ Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 8.

- ↑ Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 34.

- ↑ Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 64.

- ↑ Extensive description of the estate economy on Ahrensburg, webpage of the historical working group Ahrensburg ( Memento from December 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 166.

- ↑ a b c Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 18.

- ↑ Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 15.

- ↑ Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 17.

- ↑ Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 20.

- ↑ a b c d e Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 18.

- ^ Ahrensburg Castle Mansion . In: Stormarn Lexikon Online, accessed on March 18, 2019.

- ↑ a b schloss-ahrensburg.de - Foundation , accessed on January 23, 2017.

- ↑ a b c shz.de - The castle is spiced up for 560,000 euros, article from August 6, 2009 , accessed on December 11, 2009

- ↑ Schleswig-Holstein state budget, budget year 2007/2008, p. 54 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. pdf

- ↑ kreis-stormarn.de - Museums in Stormarn: The Ahrensburg castle , accessed on 23 January 2017th

- ↑ schloss-ahrensburg.de - Funding , accessed on December 11, 2009

- ^ Ahrensburg Castle Sparkasse Foundation. Retrieved January 23, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 6.

- ↑ a b Kurt Janssen (Ed.): Ahrensburg - Castle and Church , p. 8.

- ↑ Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 14.

- ↑ a b c d e Frauke Lühning: Schloss Ahrensburg , p. 9.

- ↑ a b Habich, D. Lafrenz, H. Schulze, L. Wilde: Schlösser und Gutsanlagen in Schleswig-Holstein , p. 204.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i G. Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , p. 138.

- ↑ G. Dehio: Handbook of the German art monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , p. 882.

- ^ HR Rosemann (ed.) Reclam's art guide: Lower Saxony, Hanseatic cities, Schleswig-Holstein . Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1967, p. 12.

- ↑ a b c d G. Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , p. 137.

- ↑ a b Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 16.

- ↑ The association's website , accessed on May 15, 2010

- ^ Adrian von Buttlar, MM Meyer: Historical Gardens in Schleswig-Holstein . 2nd Edition. Boyens & Co., Heide 1998, ISBN 3-8042-0790-1 , p. 105.

- ^ A b Adrian von Buttlar, MM Meyer: Historical Gardens in Schleswig-Holstein . 2nd Edition. Boyens & Co., Heide 1998, ISBN 3-8042-0790-1 , p. 104.

- ↑ a b Schloss Ahrensburg on gartenrouten-sh.de , accessed on December 6, 2009.

- ^ Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , p. 139.

- ^ Wilfried Pioch, The Ahrensburg Castle Church and its history. In: City of Ahrensburg (ed.), Ahrensburg: Counts, teachers and pastors. 400 years of the castle and church. Husum 1995. pp. 259-373. P. 261

- ↑ Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 67.

- ^ Heike Angermann: Diedrich Becker, Musikus. Approaching a musician and his time. 2013 ( online) (PDF; 2.3 MB) p. 23

- ↑ Abendblatt article on the Gottesbuden , accessed on January 23, 2017.

- ↑ a b Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 358.

- ↑ a b Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 21.

- ↑ Angela Behrens: The noble estate Ahrensburg from 1715 to 1867 , p. 19.

- ^ Report of the Hamburger Abendblatt from October 25, 2002 , accessed on December 6, 2009.

- ^ The "Bürgerhaus" on the website of the Ahrensburg Citizens' Association , accessed on January 23, 2017.

- ↑ a b Frauke Lühning: Ahrensburg Castle , p. 12.

- ^ Research by the historian Hans Schadendorff, webpage of the "Historisches Arbeitskreis Ahrensburg" ( Memento from December 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

Coordinates: 53 ° 40 ′ 48.4 " N , 10 ° 14 ′ 24.5" E