Albin Egger-Lienz

Albin Egger-Lienz (born January 29, 1868 in Stribach near Lienz ( East Tyrol ); † November 4, 1926 in St. Justina near Bozen ( South Tyrol )) was an Austrian painter .

Life

Albin Egger-Lienz was born out of wedlock to Maria Trojer and the church painter Georg Egger, his name was initially Ingenuin Albuin Trojer. It was not until 1877 that he was granted permission to use the Egger family name. After attending elementary school in Lienz from 1875 to 1882, he studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich with Karl Raupp , Gabriel von Hackl and Wilhelm von Lindenschmit the Elder from 1884 to 1893 through the mediation of his father and his friend Hugo Engl . J. During his studies he received the Small Silver Medal of the Academy for the image of the Holy Family and the Large Silver Medal of the Academy for Good Friday . The use of the name Egger-Lienz is documented for the first time in 1891. After completing his studies, he lived as a freelance painter alternately in Munich and East Tyrol. In 1894 he received the Small Golden State Medal in Vienna for Good Friday .

In 1899 Egger-Lienz married Laura Helena Dorothea von Egger-Möllwald (born June 11, 1877 in Vienna, † October 22, 1967 in Vienna) and settled in Vienna. In 1900 he became a member of the cooperative of visual artists Vienna and a founding member of the Hagenbund . At the Paris World Exhibition he received the bronze medal for the painting Feldsegen . In 1902 he received the Kaiserpreis for After the Peace Agreement , the painting was bought by the state. In 1909 he became a member of the Vienna Secession . In 1910 he was proposed as a professor by the college of professors at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts . The appointment was prevented by the heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand . Reasons for this are to be found in Egger's affiliation to the Secession, which Franz Ferdinand rejected, as well as in the fact that Egger had exhibited the painting Der Totentanz Anno Neun as part of the exhibition for the 60th anniversary of Emperor Franz Joseph's reign , a picture that is not patriotic was and, given the advanced age of the jubilee, could not be regarded as respectful.

In the following year Egger-Lienz settled in Hall in Tirol , where he communicated with the artists of the Brennerkreis . In 1912 he went to teach at the Grand Ducal College of Fine Arts in Weimar , where he only stayed until 1913. After a summer stay at Katwijk aan Zee in Holland, where he painted pictures of the sea and dunes, he settled in St. Justina near Bozen. In Klausen , some of his students ran an art school under his direction. In 1914 Carl Weigelt published a monograph on him.

When the First World War broke out , Egger-Lienz was already an established artist. At the end of April 1915 - before Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary - Egger-Lienz reported to the Tyrolean Standschützen , a troop that mainly belonged to age groups that were not initially subject to general conscription. The Standschützen were called up on May 19, 1915 and sworn in on the following day in Bolzano . The standing rifle unit in which Egger-Lienz served moved into the Tombio mountain fortress as a crew . The painter was to Schanz work and camouflaging of casemates used. A fortress doctor, Dr. Friedrich Pfahl from Innsbruck stated "heart problems when walking uphill" and made it possible for Egger-Lienz, who was 47 years old at the time, to return home. After returning home, Egger-Lienz reported: “I had already been in the firing line with the Standschützen for 14 days in the front line at a fortress near Riva, in the middle of the thunder of cannons. There was also fire from our fort. The crew, of which I was a member, did not need to intervene. But everything was in readiness. Our borders are so fortified that the whales can never get in without always having to go back bloody ”.

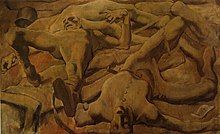

Egger-Lienz was subsequently assigned as an artistic advisor to the War Welfare Office in Bolzano. He made his sketches in the field and also small oil paintings available for reproduction for the benefit of the Red Cross , the War Welfare Office and other aid organizations. From mid-January to mid-February 1916 he worked as a war painter in Folgaria , until May 1916 in Trento . He visited high mountain positions and painted several pictures of the front, which he also made available to the Imperial and Royal War Press Quarters (KPQ) for exhibitions. He also designed war postcards and illustrations for the Tiroler Soldatenzeitung . The KPQ gave him permission to “paint at the front”, which meant that he was not accepted into the KPQ's stand and, as an official war painter , was not bound by the KPQ's tax regulations. From May 1916 onwards, Egger-Lienz only dealt with the war in free compositions painted in the studio. The monumental painting The Nameless 1914 was created during this time . In later years Egger-Lienz confessed to the nameless as one of his strongest creations: “In none of my pictures have I ever achieved so much pure form size or formal language as in the 'family' and the 'nameless'; the heads of the former as well as the bodies of the latter bear witness to it ”.

After the end of the war, he was offered a professorship at the Vienna Academy in 1919 , which he did not accept, as was a new offer in 1925. From 1923 to 1925 he worked on the design of the war memorial chapel designed by Clemens Holzmeister in Lienz, which also included the painting of Christ's Resurrection originated. After protests against the design of the chapel, among others by the dean, the Holy Office in Rome ordered a ban on worship in the chapel. It was not open to the public again until 1950.

In the last years of his life, Egger-Lienz was made an honorary doctorate from the University of Innsbruck and an honorary citizen of Lienz. Egger-Lienz regularly took part in the Bolzano Art Biennials , which took place in the Bolzano City Museum from 1922 . Josef Soyka and Giorgio Nicodemi published monographs on him. Egger-Lienz died on November 4, 1926 in the Grünwaldhof in St. Justina.

Works and influences

Egger-Lienz's oeuvre mainly includes oil paintings. He destroyed preliminary studies such as drawings and numerous works. Several of his motifs have been preserved in several pictures and versions. He also made lithographs of some motifs, such as mountain mowers .

Early stage

Egger-Lienz's artistic talent was encouraged by his father and his acquaintance, the painter Hugo Engl . They also enable him to study painting in Munich at the Academy of Fine Arts. Important influences were his teacher, the history painter Wilhelm Lindenschmit the Elder. J., and genre painting by Franz von Defregger , for example , but also Mathias Schmid and Alois Gabl . The painting Ave Maria after the Battle of Bergisel (1894/96) is designed in the style of history painting . The pieces Portrait Painter in the Country (1891) and The Application II (1898) are committed to Defreggers' manner . An important theme at this time is the religious life in the country, visible for example in the pictures Good Friday (1892/93), Holy Sepulcher (1900/01) and Christmas Eve (1903/05).

Within the history painting, Egger-Lienz developed his own composition scheme in which he broke up the predominantly static picture composition of the traditional norm and brought dynamism into the composition. In the oil painting Das Kreuz (1901) the accidental-looking image section is emphasized, the men almost pushing out of the picture, while the anonymous crowd pushes in from behind. Later, in Haspinger Anno Neun (1909), this dynamic conception is reinforced by the emphasis on the diagonal line.

Vienna - Dance of Death and Sower

In the fall of 1899 Egger-Lienz settled in Vienna. For the painting, which was still started in Munich, The Cross was given to him on the XXVIII Annual exhibition of the cooperative of visual artists awarded the Great Golden State Medal, the hoped-for monetary prize did not materialize, as did the hoped-for purchase by the public sector.

In the picture After the peace treaty in 1809 (1902) he led the history painting towards symbolic generalization. The theme of the dance of death is formally anticipated in the resignation and in the design of the group of figures. The citizens of Calais from Auguste Rodin , of whom plaster models were exhibited in the Vienna Secession in 1901 and which had greatly impressed him, were certainly an important stimulus for Egger-Lienz .

In 1904 Egger-Lienz turned to the subject of the sower, which was to occupy him until the 1920s. The model here is Jean-François Millet ( The Sower , 1851), the actual trigger was more the work of Giovanni Segantini , who is related to Millet and of whom 36 major works were exhibited in the Secession in 1901. Here too, Egger-Lienz is characterized by the long time it takes from absorbing an influence to processing it in its own works.

In 1904/05, Die Wallfahrer was created in South Tyrol , the formal conception of which shows parallels to Ferdinand Hodler's picture The Truth (1903), which was exhibited in the Secession in spring 1904 together with 30 other works by Hodler. While the first drafts for The Pilgrims had a seated Madonna and Child in the middle, Egger-Lienz replaced it with the crucified one under the influence of Hodler. With this painting Egger-Lienz achieved the breakthrough to the "monumental-decorative period".

From 1906 he dealt with the topic of the dance of death . A first oil painting was created in Längenfeld in the summer . In terms of composition, the stringing of figures dominates here, as was already used in the peace treaty and the pilgrims. In addition to Rodin's citizens of Calais , Constantin Meunier is another role model for the formal design. Egger-Lienz already knew his work from Munich, and in 1906 the Hagenbund showed an exhibition in Vienna with 148 works by Meunier. The bronze relief Retour des mineurs (The return of the miners, 1895/97) shows clear parallels to the dance of death. In the autumn of 1907 the first oil version of the dance of death was finished, in February / March 1908 he painted a version in casein technique in the Vienna studio , which enabled him to achieve the monumentality and stylization he wanted. Then he cut the first oil barrel. As a result, another 12 preserved versions or versions were created over the years.

The monumental paintings King Etzel's Entry into Vienna (1910), Haspinger Anno Neun (1908/09) and the first version of Sower and Devil (1908/09) were created using the casein technique . Egger-Lienz differed from his contemporaries, who also painted in casein, in the emphasis on the sculptural body forms and the monumentality in contrast to the decorativeness of Art Nouveau .

Other influences are impressionism , which can be found in the light-flooded works Maisernte (1906), The Mountain Mowers (1907) and The Lunch (1908).

Late work

Important for the period around 1910 and thereafter is the “strict reduction of the form in the figural”. This can also be seen in a saying by Egger, which applies to his later work: “I paint shapes, not farmers.” At this time Egger also began to deal with the major issues of being.

Central themes are fate, the tension between becoming and passing. Some of the works he painted during and shortly after the First World War are closely related to German Expressionism , especially the Finale (1918), described by Gert Ammann as “the central work in Egger-Lienz's oeuvre”. In other images of war, such as The Nameless 1914 (1916), in Totenopfer (1918) and in the Missa eroica (1918), the emphasis is on the self-contained volume, the cubic foreshortening and the distortions. In the pictures after the World War, the peasants also appear as contemporary witnesses and ambassadors of suffering and death, for example in the paintings Generations (1918/19), War Women (1918/22), and Mothers (1922/23). They appear as mute observers of an ominous world .

reception

Egger-Lienz's reception after his death was strongly influenced by political criteria. His work is often assigned to the sphere of a conservative, if not even fascist, aesthetic . While Egger-Lienz is seen by Austrian authors more as a representative of modernism and as a pacifist, international experts see him more as a forerunner of National Socialist painting.

During his lifetime, this political classification was not yet noticeable, as Leon Trotsky wrote about an exhibition at the 1909 Secession: Albin Egger-Lienz occupies the most prominent place in the exhibition, remember his name. [...] His “Haspinger”, his “Seeders” are undoubtedly and to the highest degree perfect wall painting. Carlo Carrà , one of the most important theorists of Italian Futurism , described him as one of three outstanding artists of the XIII. International Art Exhibition in Venice in 1922.

Under the National Socialists Egger-Lienz was particularly valued by Alfred Rosenberg , but this did not lead to an exhibition of Egger-Lienz's works before the annexation of Austria in 1938. In the same year, the main office arranged "fine arts" in the NSDAP together with the NS organization “ Strength through Joy ” in Berlin, a major traveling exhibition with works by Egger-Lienz. Adolf Hitler's appreciation for Egger-Lienz, which has been repeatedly claimed, is an unproven political myth , and Hitler immediately passed on to the Carinthian State Gallery the picture man and woman that was given to him by the Carinthian regional administration for his 50th birthday . In 1943, the Egger Lienz Museum, which still exists today, was opened in Bruck Castle in Lienz . The cultural policy of the National Socialists preferred the works of the early period and the middle of his oeuvre to his later work; even the war women were exhibited in 1940, as was the painting Finale in 1940/41 in the Viennese gallery Welz - albeit in a separate room . Other pictures, such as The Nameless 1914 , were reinterpreted in the National Socialist sense.

This official appreciation by the National Socialists lastingly impeded the reception of Egger-Lienz in the Second Republic. Only four solo exhibitions took place between 1945 and 1996. In 1968 Egger's birthday was ignored even in Tyrol, only in 1976 and again in 1996 there were exhibitions in the Tyrolean Provincial Museum Ferdinandeum on the anniversary of the death . According to his biographer Wilfried Kirschl , in recent years Egger's reception has deviated from the emphasis on the popular, the typical towards the designer of the war experience and the later mental images. Robert Holzbauer sees Egger-Lienz's future classification as a representative of classical modernism.

On the art market, the large number of versions and replicas of the individual pictures is seen as a price inhibitor. The market is also essentially limited to Austria. The highest price achieved for a painting by Egger-Lienz is 760,000 euros, which was paid for a version of the Dance of Death 1809 from 1921 on May 30, 2006 at an auction in Vienna's Dorotheum . The highest international price was around 208,000 euros for a version of the mountain mower from 1907, which was achieved in 2002 at Sotheby’s in London.

His works are mainly in Tyrolean museums, such as Schloss Bruck in Lienz and the Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum in Innsbruck , but also in Vienna in the Army History Museum , the Belvedere and the Leopold Museum .

In 1932, the Austrian Post published a value with the portrait of Egger-Lienz in a series of 6 items on Austrian painters. Later three more stamps were issued based on motifs by Egger-Lienz (100 Years of the Künstlerhaus, 1961; Christmas, 1969; European Family Congress, 1978).

Michael Powolny's post-war 1 schilling aluminum coin showed the figure of the devil from Egger-Lienz's painting Sower and Devil from 1921. It sparked discussions because of the motif. It was issued from 1946 to 1957 and was in circulation until 1961.

1930 in Vienna- Meidling the Egger-Lienz-Gasse named after the painter. Egger-Lienz-Platz is located in Lienz . In 1951 a memorial plaque was placed on the artist's former home at Veithgasse 3 in Vienna. There is a memorial in Längenfeld in Tyrol, where he spent his summer stays. In the Gries-Quirein district of Bolzano , Egger-Lienz-Strasse commemorates the artist.

Works (selection)

- Sunday morning (private collection), 1897, oil on canvas, 94.7 × 69.2 cm

- The pilgrims (Mannheim, Kunsthalle), 1904–1905

- The Dance of Death from Anno 09 (Vienna, Belvedere ), 1906–1908, oil on canvas, 225 × 233 cm

- Mountain Mower (Vienna, Leopold Museum), 1907, oil on canvas, 94.3 × 149.7 cm

- Macabre Dance (Lienz, City Museum), 1907

- Anno Neun (Lienz, Schloss Bruck), 1908/09, casein on canvas, 265 × 456 cm

- Man and Woman or The Human Couple (Klagenfurt, Carinthia State Museum ), 1910

- Lunch or The Soup (Vienna, Leopold Museum), 1910, oil on canvas, 91 × 141 cm

- Alpine landscape in the Ötztal (Vienna, Leopold Museum), 1911, oil on canvas, 32.5 × 52.5 cm

- Schnitter (Lienz, City Museum), 1914–1918, oil on canvas

- The Nameless 1914 (Vienna, Heeresgeschichtliches Museum ), 1916, tempera on canvas, 245 × 476 cm

- A mower (Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesmuseum ), 1916–1918, oil on canvas, 70 × 57 cm

- Finale (Vienna, Leopold Museum), 1918, oil on canvas, 140 × 228 cm

- Dead soldier from the "Missa eroica" (Vienna, Heeresgeschichtliches Museum), 1918, tempera on canvas

- Leichenfeld II (Vienna, Heeresgeschichtliches Museum), 1918, oil on canvas, 70.5 × 119.5 cm

- Ila, the artist's younger daughter (Linz, Lentos Kunstmuseum, inv. No. 155), 1920, oil on wood, 82 × 72 cm

- Die Schnitter (Vienna, Leopold Museum), around 1922, oil on canvas, 82 × 138 cm

- Die Quelle (Vienna, Leopold Museum), 1923, oil on canvas, 85 × 126 cm

- The grace (Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesmuseum), 1923, oil on canvas, 136 × 188 cm

- Christ's Resurrection (Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesmuseum), 1923–1924, oil on canvas, 197 × 247 cm

- The Farmer ( Dorotheum auction , Vienna, May 2011), 1925–1926, oil study on canvas, 70 × 99 cm

- Pilgrims (private property), 1904, oil study on canvas, 56.5 × 108 cm

literature

- Wilfried Kirschl : Albin Egger Lienz. 1868-1926. The complete work . (2 vols.). Christian Brandstätter Verlag, Vienna 1996. ISBN 3-85447-689-2

- Leopold Museum (Ed.): Albin Egger-Lienz. 1868-1926 . Exhibition catalog, Christian Brandstätter Verlag, Vienna 2008. ISBN 978-3-85033-194-4

- Heinrich Hammer : Albin Egger-Lienz In: Der Schlern 1923, pp. 165–179. (on-line)

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilfried Kirschl: Albin Egger Lienz, 1868–1926. Das Gesamtwerk , Vienna 1996, p. 267 f.

- ↑ Ludwig Hesshaimer: Miniatures from the monarchy. An Austro-Hungarian officer tells with a pencil . Edited by Okky Offerhaus, Vienna 1992, pp. 81–83.

- ↑ Adalbert Stifter Verein (ed.): Muses to the Front! Writer and artist in the service of the Austro-Hungarian war propaganda 1914-1918 . Exhibition catalog, Munich, 2003, volume 1, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Walter Reichel: "Press work is propaganda work" - Media Administration 1914-1918: The War Press Quarter (KPQ) . Communications from the Austrian State Archives (MÖStA), special volume 13, Studienverlag , Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-7065-5582-1 , p. 107 f.

- ↑ Liselotte Popelka: From Hurray to the corpse field. Paintings from the war picture collection 1914-1918. Vienna 1981, p. 58.

- ↑ quoted in Wilfried Kirschl: Albin Egger Lienz, 1868–1926. Das Gesamtwerk , Vienna 1996, p. 288.

- ↑ Sabrina Michielli, Hannes Obermair (Red.): BZ '18 –'45: one monument, one city, two dictatorships. Accompanying volume for the documentation exhibition in the Bolzano Victory Monument . Folio Verlag, Vienna-Bozen 2016, ISBN 978-3-85256-713-6 , p. 65-66 .

- ^ Obituary in the fascist Alpine newspaper of November 6, 1926, p. 6

- ^ Leopold Museum (Ed.): Albin Egger-Lienz. 1868–1926 , 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Leopold Museum (Ed.): Albin Egger-Lienz. 1868–1926 , 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Leopold Museum (Ed.): Albin Egger-Lienz. 1868-1926 . 2008, p. 23.

- ^ Robert Holzbauer: Egger-Lienz and the ideologues . In: Leopold Museum (ed.): Albin Egger-Lienz. 1868-1926 . 2008, p. 55.

- ↑ quoted from Robert Holzbauer: Egger-Lienz and the ideologues . In: Leopold Museum (ed.): Albin Egger-Lienz. 1868-1926 , 2008, p. 55.

- ↑ Carl Kraus , Hannes Obermair (ed.): Myths of dictatorships. Art in Fascism and National Socialism - Miti delle dittature. Art nel fascismo e nazionalsocialismo . South Tyrolean State Museum for Cultural and State History Castle Tyrol, Dorf Tirol 2019, ISBN 978-88-95523-16-3 , p. 165 .

- ↑ Martin Kofler: Albin Egger-Lienz and East Tyrol. The collection in the Museum of the City of Lienz Schloss Bruck between construction and restitution (1938 to the present) . In: Gabriele Anderl (Ed.): Nazi art theft in Austria and the consequences . Studien-Verlag, Innsbruck-Wien-Bozen 2005, ISBN 3-7065-1956-9 , pp. 131-144.

- ↑ quoted from Robert Holzbauer: Egger-Lienz and the ideologues . In: Leopold Museum (ed.): Albin Egger-Lienz. 1868–1926 , 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Robert Holzbauer: Egger-Lienz and the ideologues . In: Leopold Museum (ed.): Albin Egger-Lienz. 1868–1926 , 2008, p. 59.

- ↑ kron: Fatal tendency towards variation . Der Standard , February 28, 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Coin catalog: Coin ›1 Schilling colnect.com, accessed January 27, 2019.

- ^ Manfried Rauchsteiner , Manfred Litscher: Das Heeresgeschichtliche Museum in Wien , Verlag Styria , Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-222-12834-0 , p. 67.

further reading

- Albin Egger-Lienz. The person, the work, self-testimony . With contributions by Ila Egger-Lienz and Kristian Sotriffer. Haymon, Innsbruck 1996. ISBN 3-85218-227-1

- Ila Egger-Lienz: My father Albin Egger-Lienz . Deutscher Alpenverlag, Innsbruck 1939 (last 1981, ISBN 3-85395-026-4 )

- Johanna Felmayer: Egger-Lienz, Albin Ingenuin. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , p. 334 ( digitized version ).

- Maria Rennhofer: Albin Egger-Lienz. Life and work 1868–1926 . Christian Brandstätter Verlag, Vienna 2000. ISBN 3-85498-087-6

- Agnes Husslein-Arco , Helena Pereña, Stephan Koja (eds.): Dance of death: Egger-Lienz and the war. Exhibition catalog, Belvedere, Vienna, 2014, ISBN 978-3-902805-43-0 .

Web links

- Albin Egger-Lienz at Google Arts & Culture

- Holdings in the catalogs of the Austrian National Library Vienna

- Literature by and about Albin Egger-Lienz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Entry on Albin Egger-Lienz in the database of the state's memory for the history of the state of Lower Austria ( Museum Niederösterreich )

- Entry on Albin Egger-Lienz in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Works by Albin Egger-Lienz at Zeno.org .

- Brenner archive of the University of Innsbruck

- Albin Egger-Lienz: looted art under suspicion of fascism

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Egger-Lienz, Albin |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Trojer, Ingenuin Albuin (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 29, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Stribach near Lienz , East Tyrol |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 4, 1926 |

| Place of death | St. Justina , Bolzano , South Tyrol |