Giovanni Segantini

Giovanni Segantini (born January 15, 1858 in Arco ( Tyrol , Austrian Empire ); † September 28, 1899 on the Schafberg near Pontresina , Canton of Graubünden , Switzerland ; full name Giovanni Battista Emanuele Maria Segatini [ sic! ] ) Was a in Welschtirol as Austrian citizen born painter of realistic symbolism . He was considered a master of the high mountain landscape and began to paint in the open air at an early age . Segantini developed his own version of the pointillist painting technique, with the help of which he could reproduce the unbroken light of the high mountain world and increase the naturalistic effect of his pictures.

Life

origin

The Segatini family [ sic! ] Dates back to at the Adige River in Verona located Bussolengo , which by its linen - and silk weaving was known. Johannes Maria Segatini (born May 3, 1718), the great-grandfather of Giovanni Segantini, and his grandfather Anton Giovanni Segatini (born May 7, 1743) also dedicated themselves to this trade. After silk weaving and the associated trade had declined sharply in the second half of the 18th century, the grandfather emigrated with the workers to Trentino and settled as a silk weaver in Ala , where a flourishing silk industry was to develop. Eight sons were born to him between 1788 and 1802, including the youngest Agostino Segatini, who would become the artist's father. Aloisio Segatini, an older brother of Agostino, was the first of the family to settle in Trento , the younger brother followed later and gave up the old family business to become a cheese merchant.

Segantini's mother, Margherita Girardi, came from an old Fiemme Valley family who lived in Castello-Molina de Fiemme . Margherita Girardi was a direct descendant of Francesco Girardi, an imperial councilor and colonel , "who organized the Tyrolean militia and author of a publication that has become classic in military literature, the 'Handbüchl zum Exercieren'". The name Girardi is widespread in the Ladin area, and you can also find it outside the Fiemme Valley in the Rolle Pass area , at the foot of the Cimone della Pala and in the Ampezzo Valley , from where Alexander Girardi also came from.

Early Years (1858-1875)

Giovanni Battista Emanuele Maria Segatini, his real name, which he later changed to Segantini, was born in 1858 in the then Austrian Arco north of Lake Garda as the child of the carpenter Agostino Segatini (* 1802 - 20 February 1866) and his third wife, Margherita de Girardi (born September 4, 1828 in Castello , † March 3, 1865 in Trento ). A brother six years older was killed in a fire on July 20, 1858.

After the mother's early death (she died at the age of 36), the alcoholic father brought him to live with a daughter from his first marriage, Irene. The little one found this a burden, and Giovanni ran away whenever he could. In July 1865, hatred drove the half-sister so far that she wrote to the Innsbruck authorities asking them to revoke Giovanni of Austrian citizenship. This happened: According to the repressive laws that applied to the Italian rulers in the then Austrian Empire , citizenship could be withdrawn from a seven-year-old.

Segantini remained stateless all his life. In 1870 he was picked up without papers and, since his father died, he ended up in the Riformatorio Marchiondi educational institution . There he learned the trade of shoemaker. An old chaplain took care of him. He recognized his talent for drawing, told him about the painter monk Fra Angelico and allowed him to draw and model. Thanks to the intervention of his half-brother Napoleone, he was able to leave the reformatory in 1873 and worked in its photo and drug store in Borgo Valsugana until 1874 . He then came to Milan and from 1875 worked for the former Garibaldi supporter Luigi Tettamanzi, a painter of saint flags, banners and pub signs, comedian and author of historical dramas. Tettamanzi hired him as an assistant and gave him drawing lessons.

Milan (1875–1880)

In 1875 he enrolled at the Brera Art Academy in Milan , taking day courses in painting and evening courses in ornamentation . At a national exhibition of the Brera, he caused a sensation among teachers and students as early as 1879 with his first larger picture, the choir stalls of Sant'Antonio , due to the novel treatment of light.

“I was certainly not anxious to create a work of art, but simply to be active in painting. A stream of light penetrated through an open window, dousing the carved wooden seats of the choir with light. I painted this part, trying mostly to hold on to the light, and immediately realized that when you mixed the colors on the palette you got neither light nor air. So I found the means to arrange the colors real and pure by placing the colors on the canvas that I would otherwise have mixed on the palette, unmixed one next to the other and then leaving it to the retina to apply them while looking at the painting to merge their natural distance. "

The choir stalls of “Sant'Antonio”, which were illuminated through a side window, were considered an insoluble problem by the students of the perspective. They wanted to award Segantini the "Principe Umberto Prize" endowed with 5000 lire. Envious people and enemies knew how to prevent this by making the jury aware that Segantini was Austrian and not Italian. The picture was acquired by the Society of Fine Arts of Milan . He was later commissioned to make colored anatomical drawings for the students, which enabled him to acquire a good knowledge of anatomy himself.

Because of differences of opinion with the professors at the Brera, he left them after two years. In the same year he met the art critic and dealer Vittore Grubicy de Dragon (1851-1920) in the "Galleria Vittore ed Alberto Grubicy" in Milan. The gallery organized a memorial exhibition for Tranquillo Cremona (1837–1878), who died early. Segantini entered the exhibition in poor clothes and rough shoes. He was reprimanded by Grubicy, continued to study the paintings carefully, apologized, and identified himself as a painter. Thus began a relationship and friendship for life, and Segantini's financial hardship came to an end for the time being, because Grubicy procured him orders for still lifes and brought Segantini's paintings to the art market. In addition, the well-traveled Grubicy brought him into contact with reproductions of the art of his time, which was one of the few opportunities for Segantini to gain knowledge of the luminism of the Hague School , Neo-Impressionism and other artists such as Anton Mauve and Jean-François Millet and their works receive.

Brianza (1880-1886)

In 1880 Segantini moved into his first studio in Via San Marco near the Navigli in Milan, which he kept as his Milan domicile. Here he met seventeen-year-old Luigia Bugatti (1863–1938), known as Bice, the sister of his classmate and friend Carlo Bugatti , who later became a sought-after cabinet maker in Milan and Paris . Bice was the model for La Falconiera (The Falconer) from 1880, a romantic painting that reflects the painter's love. The heroine of the picture is called “Bice del Balzo” and, in the eyes of the enamored painter, “took on earthly form in the female forms of the beloved Luigia Bugatti, who from now on became his Bice.” They could not marry because he did not have the necessary papers.

In 1881 he moved with Bice to Pusiano in Brianza, a rural, hilly lake landscape between Lecco and Milan. The couple had two sons there: Gottardo Guido (1882–1974), who later became his father's painter and biographer, and Alberto (1883–1904). His third son Mario (March 1885–1916) and daughter Bianca (May 1886–1980) were later born in Milan. Mario also became a painter and Bianca published her father's writings and letters in German in 1909 in Leipzig. In 1882 the Segantini family moved into a mansion in Carella, where Segantini met the Lombard painter Emilio Longoni (1859–1932), who lived and worked in the same house for a while.

Segantini studied the "Natura morta" in detail and developed a painting close to nature in numerous still lifes. He often painted flowers because for him they embodied the pure beauty of nature. Here, on Lake Pusiano, the first version of Ave Maria auf der Überfahrt was created in 1882 , which was to be awarded two years later at an exhibition in Amsterdam. This first version has not survived.

On January 20, 1883, Segantini and Grubicy signed a contract in which Segantini authorized his patron and dealer to sign pictures with the monogram "GS", to represent him in all public and private matters and to dispose of his work and possessions.

In 1884 Segantini left Carella with his family and moved to Corneno. From 1885 to 1886 he stayed in Caglio in Lombardy , a few kilometers from Carella, for six months . In one of his most important works, An der Stange , a large-scale, light-filled and spacious composition, he summarized the experiences in the Brianza. The picture represented the sum total of his painterly development and anticipated something of his triptych Being, Becoming, and Passing .

Savognin (1886-1894)

Tired of the landscape, Segantini left the Brianza in 1886, moved to Milan with his family for six months and carried out commissioned work for the Lombard bourgeoisie. After a long excursion via Como , Livigno , Poschiavo , Pontresina and Silvaplana , he settled in Savognin in Oberhalbstein in the "Peterelli" house, where he lived with his family until 1894. Segantini processed motifs from village and alpine life into pictures in which the rural people were included in the landscape. Many of his great works were created here. So he created a new version of Ave Maria bei der Überfahrt , in which he experimented for the first time with the technique of Divisionism . One of his most popular pictures, The Two Mothers , was also created in Savognin. The work Die Scholle from 1890 is now in the Neue Pinakothek in Munich.

He had achieved fame in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, later also in Austria, but also in Japan and was visited by Max Liebermann and Ludwig Fulda . Giovanni Giacometti and the young Cuno Amiet , whom he met during a summer vacation in Stampa at Giacometti's in 1896 , received his benevolent support. As part of the world exhibition in London in 1886, Segantini was one of the best represented artists at the Italian Exhibition , which confirmed his international presence. In 1889 he was represented with works in the Italian section at the World Exhibition in Paris, and the picture Cows at the Trough from 1888 was awarded the gold medal. In his pictures he began to approach symbolism . The first “Segantini retrospective” took place in December 1891 at the Grubicy Gallery in Milan. Segantini took up relationships with the dealers Ernst Arnold in Dresden, Eduard Schulte in Berlin and others, whereby Alberto Grubicy lost the exclusive right to his works.

Barbara Uffer , Segantini's preferred model, is depicted in many of Segantini's works : among other things as a drinking girl at the fountain in Bündnerin at the fountain from 1887; as a knitting girl in a meadow in Knitting Girl from 1888; as a shepherdess under a clear blue sky in midday in the Alps from 1891 or as a sleeper next to a fence in peace in the shade from 1892. After Segantini and his family had settled in Savognin in 1886, the then 13-year-old Barbara, known as Baba, stepped in , as nanny and housemaid at the service of the family. She took care of the four children Gottardo, Alberto, Mario and Bianca and took care of the rooms. She also had to accompany Segantini with painting utensils and provisions when he worked in the countryside.

When the Segantinis moved to Maloja in 1894, Baba came with them. In 1899 she accompanied Segantini to the Schafberg, where he worked on the middle section of the triptych. After Segantini's death, she stayed with Bice and the children for five years until she left the family after a total of 19 years.

Maloja (1894–1899)

In August 1894 the Segantini family left Savognin, settled in Maloja in the Upper Engadin and moved into the "Chalet Kuoni" built by the Gotthard Railway Company engineer Alexander Kuoni from Chur ; a spacious chalet not far from Lake Sils . Segantini got in touch with the art dealers Bruno and Paul Cassirer as well as Felix Königs from Berlin, by whom he was represented. From 1896 Segantini worked in Maloja in summer and in Soglio in Bergell in winter . Here, among other things, high mountain landscapes were created using a painting technique related to Neo-Impressionism. Above all, the grandiose Alpine triptych Becoming - Being - Passing away (La vita - La natura - La morte) consisting of the parts Life , Nature and Death is known . Life originated in the vicinity of Soglio from 1896 to 1899, Nature from 1897 to 1899 on the Schafberg above Pontresina in the Engadine and Death from 1896 to 1899 at the Malojapass in the direction of Bergell. The triptych hangs in the Segantini Museum in St. Moritz .

During his time in Maloja, Segantini had a lively correspondence with the poets Angelo Orvieto (1869–1967) and Domenico Tumiati (1847–1933); the novelist Neera (pseudonym for Anna Radius Zuccari, 1846–1918), who was one of his first biographers, the Milanese late romantic Gerolamo Rovetta , with the librettist Luigi Illica , the Divisionist painter Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo and the Neapolitan poet Vittorio Pica (1866– 1930). The latter made impressionism and symbolism known to the Italian public from Paris . Finally, an exchange began with the Vienna Secessionists , who saw Segantini as a pioneer. Statelessness caused great trouble for Segantini. In Austria, however, where Emperor Franz Joseph admired his works, he was granted a certain protection.

In 1897, before a meeting in Samedan , Segantini announced a project that was supposed to be financed by Engadin hoteliers, but never came about. For the world exhibition in Paris in the spring of 1900 he had planned a panorama of the Engadine . The aim was to create a pavilion which "in the best tradition of the panorama of the 19th century would have shown the restoration of the natural beauties of the Engadine by means of a pictorial and plastic illusionism." The project envisaged a circular iron architecture with a total area of 3850 square meters, which should represent the landscape and the atmosphere of Swiss alpine life in a 360 ° panoramic view. The triptych of nature should be integrated into it. The high cost of one million francs, which should have been raised for the rent, and the resulting long negotiations, which continued until 1900, caused the project to fail.

For the illustration of a Bible, for which the publishing house "Geillustreerde Bijbel Uitgaven" in Amsterdam had founded a company with the aim of publishing the Bible in several languages at low cost, numerous artists recognized in Europe were asked to participate. Segantini delivered three drawings in 1898. The company lasted from 1896 to 1903.

He presented his thoughts and artistic views in numerous texts. In November 1898, Segantini's “Reflections on Art” - his answer to a survey by Lev Tolstoy in an article in Le Figaro in which the latter asked the artist: “ What is art? ”- published by the Vienna Secession magazine Ver Sacrum .

When Tolstoy asked “Qu'est-ce que l'art?” Segantini answered at the beginning of What is Art? : “When I wanted to alleviate the pain of the parents of a dead child, I painted the 'pain comforted by faith'; in order to consecrate the bond between two lovers, I painted 'Liebe am Lebensborn'; in order to allow the full intimacy of motherly love to be felt, I painted 'the love fruit', the 'angel of life'; when I wanted to punish the bad mothers and the vain and sterile voluptuous, I painted the 'Punishment in Purgatory', and when I finally wanted to indicate the source of all evils, I painted the 'Vanity'. "

At the end he replied: “Leo Tolstoy pretends not to know what is meant by beauty and what its meaning is. All he has to do is look at a flower; it would tell him better than any definition what beauty is. He also pretends not to know where art begins. It begins where the brutal, the artificial and the banal end. When you walk past a farmhouse with lovingly decorated flowers on the window, you can be sure that order and cleanliness will prevail inside that house, and the people who inhabit it will not be bad. This is where art begins with its benefits. "

In the middle of September 1899 Segantini climbed up the Schafberg with Barbara Uffer and his son Mario to work on the almost finished being . During the summer he had worked on Becoming and Fading . The great triptych of nature should be ready for the world exhibition in Paris. Soon after his arrival, he suffered from stomach ache, tiredness and clouded consciousness, but continued to work tirelessly. Baba hurried down to St. Moritz to see Oscar Bernhard , a doctor and friend of the painter. Together with Segantini's partner Bice, who had hurried over from Milan, he climbed the mountain, but it was impossible to help the sick man.

Giovanni Segantini died on September 28 at the age of 41 in the hut on the Schafberg, which was later named after him , on a Thursday, forty minutes before midnight. His son Mario, Dr. Oskar Bernhard and Bice. In anticipation of his coming end, but also in anticipation of his recognition, he said to his dejected wife: "I saw a large crowd down there, these people were so small, and I, I was so big." His last words should have been his: “Voglio vedere le mie montagne.” (I want to see my mountains.) - a final commitment to his beloved mountains. After his death, his young friend Giovanni Giacometti came to his deathbed and painted the revered artist.

Segantini hut around 1900

On October 1, 1899, Segantini was buried in the small cemetery of Maloja, which he had painted in the comfort of faith from 1895 to 1896 . Bice died on September 13, 1938 in St. Moritz, 39 years later. She was buried next to Giovanni. A plaque bears the inscription Da presso e da lunge in terra e in cielo uniti in vita e in morte ora e semper (near and far, on earth and in heaven, united in life and death, now and always) . Above their graves is the inscription Arte ed amore vincono il tempo (art and love defeat time). Next to Giovanni and Bice are the graves of their sons Mario, Gottardo and Alberto Segantini. The daughter Bianca was buried in Arco, where she had returned after her stay in Leipzig.

In his medical report written 14 days after the patient's death, Oscar Bernhard committed himself to the diagnosis of appendicitis . He justified the fact that he had not operated on the patient with his general weakness, the inadequate heatability of the room on the Schafberg and the impossibility of transporting him to the valley. However, the symptoms of Segantini's disease can also indicate lead poisoning . Segantini used large amounts of white lead in his painting . Measurements on the coat that Segantini wore to work show contamination with lead on his sleeves.

The artist

Segantini's real career began with the move to Brianza. Here he dealt in his artistic form of expression with Jean-François Millet , who had already anticipated style elements of Impressionism with his pictures such as Le printemps (spring) from 1868 to 1873 and only in his later landscape paintings and drawings from 1865 with hers mystical light moved closer to symbolism. Segantini only knew the Frenchman's work from photographs. Despite the relationship with Millet, however, the work of the two painters differs on closer comparison: The original studio painter Millet painted his landscapes darkly, Segantini, on the other hand, bright and in a relentless light. In a letter to the poet Tumiati on May 29, 1898, Segantini wrote:

- “In order to be able to express my emotional movements more strongly and to be able to enliven the whole milieu of my work through the poetic-painterly sensations of my mind, I emancipated myself from the cold models at first, went out in the evening in the hours of sunset and took the mood that I conveyed to the screen on the day. "

This poetically dreamy epoch coincided with his liberation from the mentally constricting life of the big city. The harmony of his rural surroundings, his infatuation with rural life and his own young household contributed to this artistic development and encouraged creativity from within.

At Segantini, people were embedded in the landscape from the start and merged with it. Millet had poetized the peasant, elevated him romantically and literarily; with Segantini the shepherds and farmers remain simple and devoid of any pathos. With Gustave Courbet, Millet discovered the peasant as an artistic theme, and the choice of this motif was an expression of a social-ethical program. Millet experienced the peasant as an intellectual, as a city dweller, seen from the outside and as a critic of urban existence. Despite the external similarity of the motifs of both artists, those of Segantini have a completely different character. He felt this clearly and also expressed it that way. He just wanted to paint his models "[...], very different from Millet, happy, beautiful and satisfied, not arousing pity, certainly more envy when you get to know them and their lives as I did."

In 1908, in the Kunstwart , a German magazine that was close to the life reform movement, Ferdinand Avenarius made the comparison with Millet and summarized it in the following statement: “Segantini does not even come close to achieving the force of the human figure, but does not even strive to achieve him. He gives his Millet man greatness, but he does not make him sole ruler. To him the great is to a different extent than Millet the whole, the land, the motherly land, or, with a change in the emphasis on emotions, 'life'. ”In contradiction to Segantini's striving to increase the greatness of natural and human life without pathos describe, his son, as a biographer, often fell into a hymn-like tone when it comes to portraying the greatness of the artist:

- "To him the artist is a priest of the noble beauty of the created, who has to put his life in the service of this enlightened goddess and, if necessary, to sacrifice."

Segantini lived in a time of accelerated industrialization, great technical achievements (completion of the Gotthard Railway in 1882) and advances in natural science. Like many artists, he saw the advance of naturalistic and materialistic ways of thinking as a danger to the spiritual, the soul and the ideal. Regarding the relationship between ideal and nature, he said: “An ideal outside of the natural has no life force lasting; but a reality without an ideal is a reality without life. "

In the biography of Segantini, his son Gottardo asked if Segantini was a naturalist or an idealist, and concluded that he was neither one nor the other. "This is no longer a naturalist who has always perfected his skills in competition with the greatest of his time through serious constant effort, that is a great idealist." To reproduce nature in an eavesdropping manner, not the "immersion in grotesque and interesting peculiarities, but rather the determination of the generally known beauties ”, was the basic direction of his endeavors.

Segantini did not want to run after the critics, not to produce so-called folk art. His pictures were not audience pictures. They caused a sensation among the creative painters, at least they were recognized where they fit into the advancing art movements. They gained a special position insofar as they were used in various places to declare war on the traditional painterly attitude. If after the death of the artist his works and his name quickly gained fame and the public made his pictures “favorites of their choice”, one cannot conclude that they were also painted as public pictures.

For a long time, the assessment of Segantini's art was determined by the fact that he painted in pointillist technique. For him, however, technology was only a means to an end. Above all, he was a painter of landscape dreams and was inspired by the high mountains to bring these dreams onto canvas. Although Segantini, seen from an art-historical point of view, belongs to the symbolists with his own technique of pointillism, he was an expressionist in his basic attitude and made use of realistic forms of expression. So he is, "with all the diversity of means, close to Caspar David Friedrich , whom he surely towers in both the painterly and the primeval nature of the experience of nature."

The alpine triptych

The panorama of the Engadine planned for the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900 could not be realized for financial reasons. Segantini reduced the Alpine Symphony intended for the panorama to seven parts and began with the three middle pieces. After sketches, he worked on the spacious pictures in which light, air, distance and background should make the true spirit of the mountains visible. Because the proposed four other images due Segantini's death self-love , charity , the work and the Avalanche for the Alpine Symphony were not finished, that's Alpine Triptych seen as a fragment of what was going Segantini: A panorama of the Engadine .

Originally the three paintings were called Armonie della vita , La natura and Armonie della morte ; the titles La vita - La natura - La morte , as well as their German translation Life - Nature - Death , were only given to the three pictures after Segantini's death. On the occasion of the “IX. Art Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists ”in the Vienna Secession in January 1901, the three pictures were renamed Becoming - Being - Passing , making the work today's Alpine triptych .

Armonia della morte was started first, but always postponed. Armonie della vita was the second of the three paintings and was started in Soglio in the fall of 1896. La natura - and by that Segantini meant the nature of the mountains - was to be "propagandistically for St. Moritz as the client of the great work, a tremendous, at that time they said 'grandiose' glorification." Segantini made a large drawing under the title Sein , die served as a demonstration object and convinced the client of the beauty of the project. After the contract was signed, Segantini used the two pictures Armonie della vita and Armonie della morte as side pieces to La natura .

In 1899 Segantini drew three cardboard boxes for the triptych and sent them to the President of the Art Commission for the World's Fair. A letter written by Segantini and translated into French by Grubicy accompanied the entry of the boxes and states that the triptych, including the lunettes , should have been twelve and a half meters wide and five and a half meters high.

Become - La vita

Werden shows the landscape near Soglio in Bergell on the Plan Luder plateau in the setting sun. In the background the Sciora group can be seen on the left and the Bondasca glacier on the right. The viewer's gaze is directed through the descending path to mother and child, the actual center of the picture. The mother is as if grown together with the Swiss stone pine and Segantini said that the picture represented "[...] the life of all things that have their roots in mother nature." The branches of the tree protrude into the sky. They represent a connection between earth and heaven, from which the gaze is drawn over the slope of the mountain down to the right to the two women on the way. The circle closes.

The box shows the bezel an allegory of the forces that give life and death. Blown by the wind, water and fire draw with death, but new life arises from their destructive power. For the medallions on the right and left the representations of self-love and charity were provided.

To be - La natura

His was created on the Schafberg above Pontresina . In the last daylight, the viewer looks at St. Moritz and the Upper Engadine lakes; in the background lies the Bernina group . The people and animals returning home are quietly integrated into the cycle of nature. Contrary to the actual circumstances, Segantini makes the foreground appear like a plateau. The valley floor with the lakes arches upwards so that it appears flatter than it actually is. The view of the sky is fixed by the low horizon. Segantini achieved its extraordinary luminosity by covering the entire sky with fine lines directed radially outwards. In the area of the sun he uses more yellow, towards the outside more and more light blue and white, whereby the lines are offset with a little red.

The lunette of the cardboard shows St. Moritz houses in a winter landscape, brightly illuminated by the moonlight. For the medallions on the right and left, the representations of alpine rose and edelweiss were intended, the symbols for alpine spring and summer.

Offense - La morte

The unfinished offense shows a wintry morning landscape at the Malojapass , in which a young dead woman is carried out of a hut. Through the fence and the horse the gaze is directed up to the clouds: The dead woman has overcome earthly life. Heaven filled with light shows hope and comfort.

In the lunette of the cardboard box, two angels carry the souls of the dead into the Christian heaven, because everything that goes away is reborn in the believing heart. In the medallions to the right and left of it, the depictions of Die Arbeit and Die Avalanche were provided.

Iltrittico della natura - La vita , the Alpine triptych , 190 × 320 cm - La natura , 235 × 400 cm - La morte , 190 × 320 cm; Becoming - being - passing away , 1898–1899, oil on canvas Segantini Museum , St. Moritz.

Gottardo Segantini on this work:

- “The structure of the entire triptych is reminiscent of the masterpieces of the Renaissance, in which the artists never tire of forcing the most varied of designs together in order to bring a religious train of thought completely to mind. The beauty of the three large pictures [...] gives rise to the thought that this God-gifted artist would have been able to create such a painterly, artistic, mental miracle in the finished work, even against the taste then and now, that of this' triptych the Nature 'a new era of painting could have started. "

reception

Effect on contemporaries

In the Ottocento, the Italian art of the 19th century, Segantini was considered the most universal painter. Art theorists ranked him as synonymous with the artists Edvard Munch , Vincent van Gogh and James Ensor . Wassily Kandinsky compared Segantini in his influential art-theoretical work On the Spiritual in Art , published in 1912, with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Arnold Böcklin , emphasizing that Segantini, "for whom even the formal imitators form a worthless train [...] is outwardly the most material, because he took completely finished natural forms, which he sometimes worked through in the smallest detail (e.g. mountain ranges, also stones, animals, etc.) and, despite the visibly material form, he knew how to create abstract shapes, which inwardly made him perhaps the most immaterial of this series is. "

The Parisian avant-garde, however, found no access to Segantini: his name and his work were quickly forgotten. The history of painting in the 19th century was taught in an all too simplified way, “by equating it with the French avant-garde and attaching importance only to revolutionary artistic means of design. [...] The consequence of this approach is that all artists or movements not directly bound to these simplified schemes are no longer part of general cultural knowledge. ”The cultural milieu of France and Segantini's all too“ foreign ”work was therefore not a point of contact for the French, despite the influence of Millet's paintings.

The only exception here was the Florentine Circle, as it had already opened up to French Impressionism between 1875 and 1880. The Ottocento was largely ignored outside the country's borders, and Anglo-Saxon and French historians stubbornly insisted on seeing 19th-century Italian art as, as Alphonse de Lamartine put it, "terre des morts". In addition, the missed World Exhibition in Paris in 1900 brought Segantini a loss of popularity; the exhibition of his Panorama of the Engadine could have confirmed his success in Paris.

Even during Segantini's lifetime, during the Meiji period from 1868 to 1912 , the Japanese familiarized themselves with his work and have remained loyal to him to this day. The Italian painter Antonio Fontanesi (1818-1882), of the Japanese Emperor in 1876 as yatoi O gaikokujin after Tokyo was called to for two years as a teacher of plein air painting to teach at the first belonging to Kōgakuryō Western Academy KOBU Bijutsu gakko owes " Japan the intellectual processing of the European point of view and the participation in the important international art movements of the 20th century. ”So Segantini is now represented in the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.

The first commemorative exhibition for Segantini opened in Milan on November 26, 1899, two months after his death.

Aftermath in the 20th century

Segantini was only perceived as a “phenomenon” in the north; south of the Alps, he was seen as a representative of Italian painting, which was breaking into the 20th century. North of the Alps, he was considered by many artists as the creator and performer of a nature-loving way of life. Segantini cannot be blamed for the fact that this later led to a backward-looking Heimatkunst.

In 1903 Paul Klee made the grotesque and satirical etching Jungfrau im Baum , which has a strong affinity for Segantini's painting The Evil Mothers and which is one of the first of a series of ten etchings that Klee called Inventions until 1905 .

In 1905, the musician Anton Webern was inspired by the Alpine triptych to create his first string quartet. During his musicological studies at the University of Vienna, Webern had taken art history as a minor and saw the painting The Plowing from 1890 in the Munich Pinakothek during a stay in Munich in August 1902 . He wrote in his diary: “I long for an artist in music, as Segantini was in painting, that would have to be a music that the man lonely, far from all the world, in the sight of the glaciers, the eternal ice and snow, The dark mountain giant writes that it should be like Segantini's pictures. ”In the summer of 1905 he completed the composition for a string quartet, which only became known from the composer's estate. The world premiere took place on May 26, 1962 in Seattle by "The University of Washington String Quartet". Becoming , being and passing away were the motto of the composition.

In 1932 Leni Riefenstahl made the mountain film Das Blaue Licht and wrote in her memoir : “Now I still missed the farmers, they were the most difficult to find. I wanted to have special faces, tough and strict types, as they are immortalized in the pictures of Segantini. "Riefenstahl had not found these types, because the" 'reality' of Segantini is always due to the artistic origin, here by Millet and Anton Mauve, filtered "

Segantini's last words “Voglio vedere le mie montagne” were made 72 years later by the sculptor Joseph Beuys , who spent the Christmas days and the turn of the year 1969/70 together with his wife Eva and their two children Jessyka and Wenzel in the Hotel Waldhaus in Sils Engadin, the title of a room installation in the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven . It is entitled Voglio vedere i miei montagne , 1971. A large cupboard with an oval mirror on the left is opposite a bed frame on the right. Between the bed and the cupboard there is a high transport box open on one side and a low wooden chest on which a piece of bog oak lies and inside of which there is a yellow cloth and a bone. A mirror smeared with grease is placed on a stool covered with sulfur. In the bed there is a photograph of Beuys dressed and with a walking stick in his hand lying in this very bed. Next to the cupboard, at head height, hangs a portrait of Beuys. “I was born here next to this closet: there on the side. The closet haunted me eerily from time to time. I had my first dreams next to this cupboard […] ”Each of these objects is marked with chalk. The Rhaeto-Romanic word “Vadrec [t]” (glacier) is written on the cupboard ; on the wooden chest “Sciora” (rocks, mountain range); on the back of the mirror "Cime" (mountain peak) as well as " Pennin " and on the bed "Walun" (valley). The butt of a rifle on the wall is labeled "Think". All objects, cupboard, transport box, wooden chest, stool and bed are connected on the floor with a copper construction. From the ceiling, in the middle of the triptych-like semicircle of the installation, hangs a round lamp that reaches down to the floor and brightly illuminates a round piece of felt.

"As the Segantini mountains assure the cycle of growth and decay, so in the installation [by Beuys] the accidental life becomes a necessity." Beuys breaks through Segantini's fateful symbolic vision. For Beuys, the flow of the cycle can be shaped and influenced.

At Segantini, Beuys was attracted by the “holistic claim, the immersion of humans and animals in natural events, the cyclical rhythm of life and decay. 'Make art a worship service', declared the pantheist Segantini and demanded that the new cult should be rooted in nature, the mother of life, should be connected to the invisible life of the earth and the universe. "

In 1974, the British rock band Yes released a compilation of two albums called Yesterdays . Designed by the fantasy artist Roger Dean , the motif of the interchangeable front side goes back to Giovanni Segantini's painting The Punishment of the Voluptuous from 1891. The front shows two withered, intertwined tree trunks at the left and right edges. At the top right is the Yes logo and the album title. In the center of the picture hovers a young, undressed woman.

In 1999 the Israeli-Swiss composer Yehoshua Lakner performed his “Segante” project through Giovanni Segantini in the domed hall of the main building of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich , as well as in Milan and Bratislava .

The Italian composer and pianist Ludovico Einaudi inspired the three paintings to Segantini Alpine Triptych with its themes nature, life and death 2007 Divenire , a suite for piano, two harps and orchestra.

"Sentiero Segantini"

In 1994 (100 years of Segantini in Maloja), the Basel photographers Dominik Labhard and Hans Galli initiated a walk, the so-called "Sentiero Segantini", which connects the important stages of Segantini's work in Maloja and documents them with display boards. The route begins at the “Casa Segantini”, Segantini's home and studio, and ends at the “Chiesa Bianca” church, where Segantini was laid out and painted by Giovanni Giacometti . Today the church is owned by Segantini's granddaughter Gioconda Leykauf, who, with the help of sponsors, saved the building from decay and had it restored. Today it is used for exhibitions and concerts.

From Segantini's house the path leads to a glacier mill , which Segantini used for Vanity , and on to Majensäss Blaunca northeast of Maloja above Lake Sils. Here a panel shows Segantini's painting The Two Mothers . Continue to the former site of the so-called "Taverna americana", a stone hut, which Segantini pictured offense abbildete. From the point where the offense emerged from the triptych, the path leads to the penultimate station on the path, the Maloja cemetery, where Segantini painted the picture of Faith .

The "Senda Segantini" long-distance hiking trail connects the late focal points of the painter's work. It starts in Thusis and ends in Pontresina.

Refuges

Several refuge huts are named after Segantini : The Chamanna Segantini above Pontresina in the Languard group, the Rifugio Giovanni Segantini (Rifugio Amola) 2371 m, with the valley town of Pinzolo in the Presanella group and the "Baita Segantini" 2170 m, at Passo Costazza, in the Pala group in the Dolomites .

Awards (selection)

- 1883: Gold medal for Ave Maria on the crossing , 1882 (1st version); World Exhibition Amsterdam.

- 1886: Gold medal for Ave Maria on the crossing , 1886 (2nd version); World Exhibition in Amsterdam.

- 1886: Gold medal for An der Stange , 1886; World Exhibition in Amsterdam.

- 1889: Gold medal for cows at the drinking trough , 1888; World Exhibition in Paris .

- 1892: Gold medal for lunch in the Alps , 1891; Munich.

- 1892: Gold medal for The Plowing , 1890; National show in Turin.

- 1895: Prize of the Italian State for Il Ritorno al paese natio , 1895; International art exhibition in Venice (acquired from the Berlin State Museums in 1901).

- 1896: Golden State Medal for The Two Mothers , 1889; Association of Austrian Visual Artists.

- 1897: Large gold plaque for love at the fountain of life , 1896; International art exhibition Dresden .

Exhibitions (selection)

- 1891: Giovanni Segantini , Galleria Vittore ed Alberto Grubicy, Milan.

- 1894: Esposizioni Riunite al Castello Sforzesco. Omaggio a Segantini , Sforza Castle , Milan.

- posthumously

- 1901-1902: IX. Art exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists , Vienna Secession , Vienna.

- 1904: International art exhibition , Kunstpalast , Düsseldorf.

- 1910: Exposition du Salon d'Automne , section Italienne, Paris.

- 1912: International art exhibition of the Sonderbund of West German Art Friends and Artists 1912 , Am Aachener Tor, Cologne.

- 1924: Modern Italian Paintings , Tate Gallery , London.

- 1926: XVI Biennale internazionale d'Arte , Expositione individuale di Giovanni Segantini , Venice.

- 1930: Exhibition of Italian Art at Burlington House , Royal Academy of Arts , London.

- 1935: Giovanni Segantini , 1858–1899, Kunsthalle Basel , Basel.

- 1938: XXVI Biennale internazionale d'Arte , Venice.

- 1964: European art at the turn of the century. Secession , House of Art , Munich.

- 1976/1977: The world of Giovanni Segantini , Swiss Institute for Art Research , Zurich.

- 1976/1977: Segantini - a lost paradise? Segantini - un paradiso perduto? Thearena-Rote Fabrik, ETH Zurich Center & Hönggerberg , Zurich / Chur Industrial School, Chur / St. Gallen University of Commerce, St. Gallen / Glarus Art Museum , Glarus / Aargauer Kunsthaus , Aarau / Museo della Citta, Milano / Munich Art Association , Munich

- 1977: The Alps in Swiss Painting , Odakyu Grand Gallery, Tokyo / Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur.

- 1990–1991: Giovanni Segantini, 1858–1899 , Kunsthaus Zürich , Zürich / Belvedere , Vienna.

- 1997: Voglio vedere le mie montagne. The Gravity of the Mountains 1774–1997 , Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau / Kunsthalle Krems , Krems.

- 1999: Armonia della vita - Armonia della morte. Giovanni Segantini: A retrospective , St. Gallen Art Museum , St. Gallen.

- 1999: Giovanni Segantini, 1858–1899. Exhibition on the 100th anniversary of death , Segantini Museum St. Moritz, St. Moritz.

- 2011: Segantini , Fondation Beyeler , Riehen near Basel.

- 2011: 画家 ジ ョ ヴ ァ ン ニ ・ セ ガ ン テ ィ ー ニ 展 (Gakka Giovanni Segantini-ten) Exhibition of the collection of the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation , Tokyo

- 2013: Decadence - Positions of Austrian Symbolism , Belvedere, Vienna.

Works

A total of around 450 works by Segantini are known.

| image | title | year | Size / material | Owner / collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Natura morta con S. Cecilia Still life with S. Cecilia |

1878 | 74.5 × 54 cm tempera on paper on cardboard |

Civica Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan |

|

Il coro di Sant'Antonio The choir of Sant'Antonio |

1879 | 119.5 × 84 cm oil on canvas |

Private collection |

|

I pittori dell'oggi The saint painters of today |

1881 | 76.5 × 44 cm oil on canvas |

Bündner Art Museum |

|

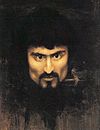

Autoritratto a vent'anni Self-portrait at the age of twenty |

1879-1880 | 35 × 26 cm oil on canvas |

Commune di Arco, Arco |

|

La falconiera The falconer (with Bice as a model) |

1879-1880 | 143 × 106 cm oil on canvas |

Musei Civici del Castello Visconteo, Pavia |

|

Paesaggio con donna su un albero Landscape with a woman in a tree |

1880–1883, unfinished | 68.5 × 104.5 cm oil on canvas |

Sturzenegger Foundation Museum Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen |

|

Autoritratto self-portrait |

1882 | 52 × 38.5 cm oil on canvas |

Gottfried Keller Foundation Segantini Museum , St. Moritz |

|

I Zampognari in Brianza The bagpipers of Brianza |

1883-1885 | 107.2 × 192.2 cm oil on canvas |

National Museum of Western Art , Tokyo |

|

Pianura sull'imbrunire level at dusk |

1883-1885 | 80 × 100 cm oil on canvas |

Beat Curti collection |

|

La benedizione delle pecore The blessing of the sheep |

1884 | 189 × 120 cm oil on canvas |

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

L'ultima fatica del giorno The last effort of the day |

1884 | 117 × 82 cm oil on canvas |

Szépművészeti Múzeum , Budapest |

|

A messa prima stair study |

1884-1885 |

|

Bündner Kunstmuseum , Chur |

|

A messa prima early mass 2nd version after painting over La penitente |

1884-1885 | 108 × 211 cm oil on canvas |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation , St. Gallen Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

La penitente The Sinner 1st version before overpainting |

1884-1885 | 108 × 211 cm oil on canvas |

|

|

Pastorello con agnellino Shepherd boy with lamb |

around 1885 | 42 × 27.5 cm pastel and colored chalk on watercolor paper |

Private property Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Ritratto della Signora Torelli Portrait of Mrs. Torelli |

1885-1886 | 101 × 74.5 cm oil on canvas |

Private collection, New York |

|

Ritratto di un morto Portrait of a dead man |

1886 | 41 × 59 cm oil on canvas |

Gottfried Keller Foundation Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

|

Alla stanga on the pole |

1886 | 169 × 389.5 cm oil on canvas |

Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna , Rome |

|

Ave Maria a trasbordo Ave Maria during the crossing 2nd version |

1886 | 120 × 93 cm oil on canvas |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation, St. Gallen Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

La portatrice d'acqua The water carrier |

1886-1887 | 74 × 45.5 cm oil on canvas |

Privately owned |

|

Il bagno del bambino The child's bath |

1886-1887 | 65 × 49.5 cm oil on canvas |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation, St. Gallen Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

La tosatura delle pecore sheep shearing |

1886-1887 | 65 × 50.5 cm oil on canvas |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation, St. Gallen Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Costume Grigionese Bündnerin at the fountain |

1887 | 54 × 79 cm oil on canvas |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation, St. Gallen Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Ritratto di Vittore Grubicy Portrait of Vittore Grubicy; Cutout |

1887 | 151 × 91 cm oil on canvas |

Museum of Fine Arts , Leipzig |

|

I miei modelli My models |

1888 | 65.5 × 92.5 cm oil on canvas |

Kunsthaus Zurich , Zurich |

|

Allo scogliersi delle nevi When the snow melts |

1888 | 66 × 98 cm oil on canvas |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation, St. Gallen Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Ragazza che fa la calza Knitting girl |

1888 | 53 × 91.5 cm oil on canvas |

Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich |

|

Vacche aggiogate cows at the drinking point |

1888 | 83 × 139.5 cm oil on canvas |

Gottfried Keller Foundation, Kunstmuseum Basel , Basel |

|

Il frutto dell'amore The fruit of love |

1889 | 88.2 × 52.2 cm oil on canvas |

Museum of Fine Arts, Leipzig |

|

Le due madri The two mothers |

1889 | 157 × 280 oil on canvas |

Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan |

|

L'Aratura Plowing |

1890 | 116 × 227 cm oil on canvas |

New Pinakothek , Munich |

|

Ritorno dal bosco Return from the forest |

1890 | 64 × 95 cm oil on canvas |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation, St. Gallen Segantini Museum St. Moritz, St. Moritz |

|

Mezzogiorno sulle alpi Midday in the Alps |

1891 | 77.5 × 71.5 cm oil on canvas |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation, St. Gallen Segantini Museum St. Moritz, St. Moritz |

|

Il castigo delle lussuriose The punishment of the voluptuous |

1891 | 99 × 173 cm oil on canvas |

Walker Art Gallery , Liverpool |

|

Capriolo morto Dead deer |

1892 | 55.5 × 96.5 cm oil on canvas |

Gottfried Keller Foundation Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Mezzogiorno sulle alpi Midday in the Alps |

1892 | 85.5 × 79.5 cm oil on canvas |

Ohara Museum of Art, Kurashiki, Japan |

|

Riposo all'ombra rest in the shade |

1892 | 44 × 68 cm oil on canvas |

Private collection Christoph Blocher |

|

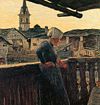

Sul balcone on the balcony (detail) |

1892 | 64.5 × 41 cm oil on canvas |

Gottfried Keller Foundation Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur |

|

Autoritratto self-portrait |

1893 | 34.4 × 24.2 cm Conté pen and pencil on paper |

Deposit from the Otto Fischbacher Giovanni Segantini Foundation, St. Gallen Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Donna alla fonte woman at the source |

1893-1894 | 71.5 × 121 cm oil on canvas |

Museum Oskar Reinhart , Winterthur |

|

Pascoli alpini alpine pastures |

1893-1894 | 169 × 278 cm oil on canvas |

Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich |

|

L'angelo della vita angel of life |

1894 | 216 × 217 cm oil on canvas |

Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan |

|

L'angelo della vita angel of life |

1894 | 275.5 × 212 cm oil on canvas |

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Le cattive madri The bad mothers |

1894 | 120 × 225 cm oil on canvas |

Belvedere , Vienna |

|

Autoritratto self-portrait |

1895 | 59 × 50 cm charcoal with gold dust and traces of chalk on canvas |

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Il ritorno al paese natio return home |

1895 | 161 × 299 cm oil on canvas |

Old National Gallery , Berlin |

|

Il dolore confortato dalla fede of faith |

1895-1896 | 151 × 131 cm oil on canvas |

Hamburger Kunsthalle , Hamburg |

|

L'amore alla fonte della vita Love at the source of life |

1896 | 70 × 98 cm oil on canvas |

Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan |

|

Pascoli di primavera spring pasture |

1896 | 95 × 155 cm oil on canvas |

Pinacoteca di Brera , Milan |

|

Pine branch |

1897 | 32 × 77.5 cm oil on canvas |

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

La propaganda The sower |

1897 | 51.3 × 53.7 cm Black and white chalk on paper |

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

La vanità The vanity |

1897 | 78 × 126 cm oil on canvas |

Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich |

|

Le due Madri The two mothers |

1899-1900; finished by Giovanni Giacometti after Segantini's death . | 69 × 125 cm oil on canvas |

Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur |

|

Iltrittico della natura La vita Life |

1898-1899 | 137 × 108 cm charcoal and Conté pen on cardboard |

Foundation for Art, Culture and History, Winterthur

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Iltrittico della natura La natura Nature |

1898-1899 | 137 × 127 cm charcoal and Conté pen on cardboard |

Foundation for Art, Culture and History, Winterthur

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

|

Iltretico della natura La morte Death |

1898-1899 | 137 × 108 cm charcoal and Conté pen on cardboard |

Foundation for Art, Culture and History, Winterthur

Segantini Museum, St. Moritz |

literature

- Primary literature

- Wilhelm Kotzde (foreword): Giovanni Segantini. Edited by the Free Teachers' Association for Art Care, Mainzer Volks- und Jugendbücher, Josef Scholz, Mainz 1908 (portrait & 17 plates). Cover by Max Wulff.

- Gottardo Segantini: Giovanni Segantini. With 16 multicolored and 48 monochrome panels and 99 images in the text. Rascher, Zurich 1949.

- Franz Servaes: Giovanni Segantini. His life and his work. Klinkhardt & Biermann, Leipzig 1907.

- Beat Stutzer (Ed.): Giovanni Segantini. In dialogue with symbolism and futurism, Ferdinand Hodler and Joseph Beuys. With contributions by Oskar Bätschmann , Matthias Fischer, Paul Müller, Eva Mongi-Vollmer and Beat Stutzer. Segantini Museum , St. Moritz; Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 2014, ISBN 978-3-85881-439-5 .

- Beat Stutzer: Giovanni Segantini. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . July 6, 2015 , accessed April 1, 2020 .

- Luigi Villari: Giovanni Segantini. The story of his life together with seventy five reproductions of his pictures in half tone and photogravure. T. Fisher Unwin, London 1901.

- Hans Zbinden: Giovanni Segantini. Life and work. Paul Haupt Publishing House , Bern 1964.

- Bianca Zehder-Segantini (Ed. And editing): Giovanni Segantini's writings and letters. Zurich: Rascher Verlag, 1934.

- Secondary literature

- Karl Abraham : Giovanni Segantini. An attempt at psychoanalysis. (= Writings on applied psychology, issue 11), F. Deuticke , Leipzig / Vienna, 1911/1925. on-line

- Reto Bonifazi, Daniela Hardmeier, Medea Hoch: Segantini. A life in pictures. Werd, Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-85932-280-X .

- Gian Casper Bott : Giovanni Segantini. Teaching material publisher, Canton of Graubünden, 1999.

- R. Eschmann: Experience of death in the work of Giovanni Segantini , Göttingen: V & R unipress, 2016.

- Herta E. Harsch: The Fruit of Love by Giovanni Segantini. A psychoanalytic contribution. In: Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig, Jb. 08/09, Leipzig 2010, pp. 64–77.

- Herta E. Harsch: Again Abraham and Segantini: About a mistake by Abraham . In: Luzifer-Amor, issue 61 (21st year), Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt a. M. 2018 pp. 24–39.

- Emil Heilbut : Giovanni Segantini. In: Art and Artists. Illustrated monthly for fine arts and applied arts. Bruno Cassirer's publishing house, Berlin 1903, vol. 1, pp. 47–58.

- Annie-Paule Quinsac: Segantini: Catologo Generale. Mondadori Electa, 1982, ISBN 88-435-0731-1 , (Italian).

- Beat Stutzer: Look into the light. New reflections on the work of Giovanni Segantini. Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-85881-159-9 .

- Beat Stutzer, Gioconda Leykauf-Segantini: Segantini. Illustrated book. Montabella 1999, ISBN 3-907067-02-9 , (multilingual).

- R. Wäspe: Segantini Giovanni. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 12, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2001-2005, ISBN 3-7001-3580-7 , p. 108 f. (Direct links on p. 108 , p. 109 ).

- Bernhard Wiebel: Censorship and realization of the exhibition "Segantini - a lost paradise?" / "Segantini - un paradiso perduto?" Critical art studies around 1975. In: * Martin Papenbrock , Norbert Schneider (ed.): Art history after 1968. V&R unipress, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-89971-617-7 , pp. 125–142, excerpts in Google books .

- Exhibition catalogs

- Felix Baumann, Guido Magnaguagno (foreword): Giovanni Segantini. 1858-1899. Kunsthaus Zürich , 1990 (November 9, 1990 to February 3, 1991).

- Emil Bosshard, Hansjakob Diggelmann, Therese Fischer u. a. (Ed.): The world of Giovanni Segantini - an exhibition of texts and images. Swiss Institute for Art Research , Zurich, 1976/1977.

- Irma Noseda , Bernhard Wiebel (curators): Segantini - a lost paradise? Segantini - un paradiso perduto? Ed. Union of Culture, Education and Science GKEW Zurich, Zurich 1976, ISBN 3-7183-0001-X (German and Italian).

- Dieter Ronte, Oswald Oberhuber (foreword): Giovanni Segantini. 1858-1899. Vienna 1981 ( Museum of Modern Art Ludwig Foundation, Vienna . Museum of the 20th Century, Vienna, July 10 to August 23, 1981 and Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum , Innsbruck, September 3 to October 4, 1981).

- Beat Stutzer, Roland Wäspe (ed.): Giovanni Segantini. Gerd Hatje, Ostfildern 1999 ( Kunstmuseum St. Gallen , March 13 to May 30, 1999; Segantini Museum , St. Moritz, June 12 to October 20, 1999), ISBN 3-7757-0561-9 .

- Diana Segantini, Guido Magnaguagno, Ulf Küster (curators): Segantini . Fondation Beyeler , Riehen / Basel, January 16 to April 25, 2011, ISBN 978-3-905632-86-6 .

- Heinz P. Adamek : Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899), pioneer of modernity - forgotten Austrian. In: "Art Chords - Diagonal. Essays on Art, Architecture, Literature and Society". Vienna: Böhlau 2016 ISBN 978-3-205-20250-9 , pp. 18–31.

- Fiction

- Raffaele Calzini: Segantini. Novel of the mountains. Schünemann 1939.

- Asta Scheib : The most beautiful thing I saw. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-455-40196-7 .

Movies

- Giovanni Segantini - Life and Work. (Alternative titles: Giovanni Segantini - Life and Work. , Giovanni Segantini - Sa vie et son oeuvre , Giovanni Segantini - La vita e l'opera , Giovanni Segantini - Vida y obra ) Documentary, Switzerland, 1990, 45 min., Script and director : Gaudenz Meili , commentary: Guido Magnaguangno, speaker: Wolfgang Reichmann , Dinah Hinz , Ingold Wildenauer, the premiere took place on November 9, 1990 at the Kunsthaus Zürich , summary by Gaudenz Meili, film scenes and preview of The Roland Collection .

- Giovanni Segantini - Tramp and Star. Documentary, (1st part), Switzerland, 2013, 30 min., Script and direction: Beat Rauch, production: NZZ , series: NZZ Format, first broadcast: October 17, 2013, table of contents and preview by NZZ.

- Giovanni Segantini - Light and Landscape. Documentary, (2nd part), Switzerland, 2013, 29:30 min., Written and directed by Beat Rauch, production: NZZ, series: NZZ Format, table of contents and preview by NZZ.

- Giovanni Segantini - Magic of Light . (Alternative title: Giovanni Segantini - Magia della luce. ) Documentary, Switzerland, 2015, 81:46 min., Script and director: Christian Labhart , speaker: Bruno Ganz , Mona Petri , production: SRF SRG , cinema release (Switzerland): 11. June 2015, table of contents, film scenes and preview from movies.ch , review in outnow.ch .

Web links

- Publications by and about Giovanni Segantini in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Literature by and about Giovanni Segantini in the catalog of the German National Library

- Comprehensive internet information about Giovanni Segantini - segantini.com

Exhibitions

- Segantini Museum St. Moritz

- Works by Giovanni Segantini at Zeno.org .

- Giovanni Segantini on kunstaspekte.de

Biographies

- Dora Lardelli: Segantini, Giovanni Battista Emmanuele Maria. In: Sikart

- Biography of Giovanni Segantini at cosmopolis.ch , September 1999

Notes and individual references

Unless otherwise noted, the main article is based on Annie-Paule Quinsac's biographical compilation of Segantini's life in: Giovanni Segantini. 1858-1899. Kunsthaus Zürich 1990, p. 225 ff.

- ↑ a b Beat Sulzer, Roland Wäspe (Ed.): Giovanni Segantini. Verlag Gerd Hatje, Ostfildern 1999, p. 200.

- ^ Michael Petters: Inter Media. Diversity and reduction. (Approval work), Munich 2001, p. 13 f., (PDF file; 405 kB), in: michael-petters.de , accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ a b silk weavers and mountain aristocrats. Reprinted from: Tiroler Almanach / Almanaco Tirolese , born 1980/10. Output. In: Dieter Ronte, Oswald Oberhuber (preface): Giovanni Segantini. 1858-1899. Vienna 1981 (Museum of Modern Art. Museum of the 20th Century, Vienna 10 July to 23 August 1981 and Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck 3 September to 4 October 1981), p. 12.

- ↑ Annie-Paule Quinsac (compilation): biography. In: Giovanni Segantini. 1858-1899. Kunsthaus Zürich 1990, p. 225.

- ↑ Wolfgang Müller: Personal riddle. Biography. In: Zeitmagazin , September 20, 2012, No. 39, p. 52.

- ^ A b Hans Zbinden: Giovanni Segantini. Life and work. Paul Haupt Verlag, Bern 1964, p. 11.

- ↑ Later record , in: Schriften und Letters , pp. 18 f.

- ↑ Gottardo Segantini: Giovanni Segantini. Rascher, Zurich 1949, p. 24.

- ^ Matthias Frehner : A realistic symbolist. On the 100th anniversary of the death of Giovanni Segantini. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung / kirchen.ch , September 25, 1999, accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Gottardo Segantini, Zurich 1949, p. 26.

- ^ Gian-Nicola Bass: Film about the exhibition Gottardo Segantini. July 14, 2018, accessed September 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Beat Sulzer, Roland Wäspe (ed.): Giovanni Segantini. Ostfildern 1999, p. 201.

- ↑ Comitato Segantini St. Moritz (ed.): Giovanni Segantini and the Segantini Museum in St. Moritz. Engadin Press, Samedan 1968, unpag.

- ↑ The interest in Segantini was awakened through Hermann Hesse's Peter Camenzind , who was translated into Japanese and in whom Segantini's work plays a role.

- ↑ Hans Zbinden, Bern 1964, p. 39

- ^ Sights in Engadin St. Moritz: Atelier Segantini, Maloja. In: engadin.stmoritz.ch, accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Annie-Paule Quinsac: The Segantini case. Fluctuations in the history of reception and the significance of his work today. In: Giovanni Segantini. 1858-1899. Kunsthaus Zürich 1990, p. 21.

- ↑ a b c Today , “Love at the source of life” , “The fruit of love” and “The wicked mothers” are common for the three work titles .

- ↑ What is art? , in: Schriften und Letters , p. 42 ff.

- ↑ a b Michael Hurni, Diana Segantini: A victim of his profession? In: NZZ , April 6, 2013, p. 66.

- ↑ Hans Zbinden, Bern 1964, p. 58.

- ↑ a b Gottardo Segantini, Zurich 1949, p. 52.

- ↑ Hans Zbinden, Bern 1964, p. 16.

- ↑ a b Hans Zbinden, Bern 1964, p. 18.

- ↑ a b Gottardo Segantini, Zurich 1949, p. 39.

- ↑ Gottardo Segantini, Zurich 1949, p. 40 ff.

- ↑ Hans Zbinden, Bern 1964, p. 7 ff.

- ↑ Comitato Segantini St. Moritz (ed.), Samedan 1968, unpag.

- ↑ Gottardo Segantini, Zurich 1949, p. 86.

- ^ Kunsthaus Zürich 1990, p. 198.

- ^ Dora Lardelli: Segantini's panoramas and other Engadine panoramas. Segantini Museum, St.Moritz 1991.

- ↑ Gottardo Segantini, Zurich 1949, p. 87.

- ↑ Wassily Kandinsky (1912): About the spiritual in art. In: geocities.jp , accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ a b Annie-Paule Quinsac: The Segantini case. Fluctuations in the history of reception and the significance of his work today . In: Kunsthaus Zürich 1990, p. 19.

- ↑ ア ン ト ニ オ • Fontanesi, Antonio. In: Mie Prefectural Art Museum , accessed February 17, 2018, MIE Prefectural Art Museum website (Japanese)

- ↑ Giovanni Segantini 1858–1899. Biography, biography, life and work. In: cosmopolis.ch , accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ^ Paul Klee: Virgin in the Tree from Inventions. 1903. In: Museum of Modern Art , [1] , accessed February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Hans and Rosaleen Moldenhauer: Anton von Webern. Chronicle of his life and work . Zurich 1979, p. 65 f.

- ^ A b Günter Metken: From Montesquiou to Beuys . In: Kunsthaus Zürich, 1990, p. 33.

- ^ Beat Stutzer: Segantini, Joseph Beuys and contemporary art. In: Beat Stutzer (Ed.): Giovanni Segantini. In dialogue with symbolism and futurism, Ferdinand Hodler and Joseph Beuys. With contributions by Oskar Bätschmann , Matthias Fischer, Paul Müller, Eva Mongi-Vollmer and Beat Stutzer, Segantini Museum , St. Moritz, Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 2014, p. 93.

- ↑ "When I do the environment 'voglio vedere [i miei montagne]', I mean the archetypal idea of the mountain: the mountains of the self." - Quote from Joseph Beuys in: Ilka Becker: The mountains of the self. Mineral kingdom and mountain world in the work of Joseph Beuys. Reprint from the Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch , Volume LVIII, 1979, Dumont Buchverlag Cologne, Cologne 1997, p. 139.

- ↑ Götz Adriani , Winfried Konnertz , Karin Thomas: Joseph Beuys . Cologne 1994, p. 121.

- ↑ Ilka Becker: The mountains of the self. Mineral kingdom and mountain world in the work of Joseph Beuys. Dumont Buchverlag Cologne, Cologne 1997, p. 137.

- ^ Theodora Vischer: Joseph Beuys. The unity of the work. Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter König, Cologne 1991, p. 211.

- ↑ After the Celtic mountain god Penninus (Celtic pen : mountain peak), who gave the name to the Pennines in England, the Pennine Alps in Switzerland and the Apennines in Italy.

- ^ Günter Metken, In: Kunsthaus Zürich, 1990, p. 42.

- ↑ Biography of Yehoshua Lakner. In: composer.ch , (German), accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Lukas Steimle: Ludovico Einaudir. In: Kulturpegel.de , April 8, 2011, accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Elfriede Schneider: Hoferin leaves the church in the village. ( Memento from August 1st, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ). In: Frankenpost , April 9, 2009.

- ↑ Hiking in Switzerland in the footsteps of the painter Giovanni Segantini. In: graubuenden.ch , accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Chamanna Segantini. In: segantinihuette.ch , accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ^ Rifugio Giovanni Segantini (Rifugio Amola). In: kreiter.info , accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Baita Segantini. In: kreiter.info , accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Fondation Beyeler shows Giovanni Segantini. In: kultur-online.net , accessed on February 17, 2018.

- ↑ Nihon FISBA. ( Memento of May 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). In: fisba.co.jp , accessed February 17, 2018.

- ^ Dieter Ronte, Oswald Oberhuber (preface): Giovanni Segantini. 1858-1899. Vienna 1981, p. 8.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Segantini, Giovanni |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Segatini, Giovanni Battista Emmanuele Maria (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian painter of symbolism |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 15, 1858 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Arco ( Tyrol , Austrian Empire ) |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 28, 1899 |

| Place of death | near Pontresina , Canton of Graubünden , Switzerland |