Riots against the new tax on stamp paper

The revolts against the new tax on stamped paper , in French Révoltes du papier timbré , were a series of contiguous revolts against the fiscal policy of the ancien régime under the rule of Louis XIV in France . From April to September 1675 it covered Brittany and Aquitaine with a focus on Bordeaux as a result of a tax increase, including on stamped paper, which was required when drawing up documents .

background

Dutch War

Louis XIV declared war on the United Netherlands in 1672 . But in contrast to the successful campaigns in the war of devolution (1667–1668), the French army was stopped after an initially rapid advance on June 20, 1672 by floods, which the Dutch triggered by opening locks and dams. The war dragged on and Louis XIV soon found himself facing an anti-French coalition. The Dutch fleet threatened the French coasts, especially those of Brittany. After landing on Belle-Île in 1673 and another on Île de Groix in 1674, she crossed the Breton coast in April and May 1675, which seriously disrupted the Bretons' trade in goods.

Tax increases

New taxes were levied to finance the war. First, the stamped paper was taxed in April 1674. It was required for all legal records, such as wills, sales contracts or civil status registers . The tariff was based on the format and type of certificate. This created general dissatisfaction, particularly in Rennes , the provincial administrative and judicial capital, as it increased the price of documents for a private individual and decreased the number of cases for legal practitioners. On September 27, 1674, the sale of tobacco was declared an exclusive right of the king, who levied a tax on it and leased it. The tenants and assistants authorized for resale bought the supplies previously intended for free sale from the dealers. This reorganization of the trading cycle affected the distribution of tobacco for smoking and chewing and heightened public anger.

At the same time, a new tax was imposed on all pewter items , even if they were bought long ago. This angered the wealthy farmers and innkeepers, who passed them on to their guests through increased prices. After all, non-nobles in possession of a fief were required to pay an annual income as a tax every twenty years. In the same year, the French West India Company was dissolved and the French Crown took over direct administration of the New France colony in North America .

Starting point in Brittany

These new taxes and threats were part of a difficult economic situation in Brittany. A recession in trade and industry was felt since 1671. The province was then very populous with about 10% of the total population of the kingdom. It had been spared famine and epidemics since the 1640s . However, in the years 1660 to 1670 Brittany entered a phase of economic bottlenecks. These were the consequences of Louis XIV's war policy, the simultaneous sharp rise in taxes and the structural weaknesses of agriculture. According to the correspondence between Duke de Chaulnes , governor of Brittany , and Jean-Baptiste Colbert on August 8, 1671, for example, the trade in wine and cloth fell by two thirds. The nickname of the duke was incidentally due to its unpopularity "fat pig" (French gros cochon , Breton high lart ). Income from land leases also fell by a third, causing general deflation, with the exception of fees and salaries of judicial officers.

The system of certain leases, called domaines congéables , which was particularly widespread in lower Brittany, regulated the relationship between the farmers who worked the land and the owners. It has been questioned by some as it did not encourage farmers or seigneurs to invest and promote cultivation methods, as if the owners gave notice, they would have to reimburse the farmers for the value of any improvements to the land and buildings. The latter, in turn, in view of their declining income since 1670, demanded their other rights in the form of natural produce and money in a more pedantic way. As a result, payments were refused in the Carhaix area in 1668 . Jean Meyer questions the role of the lease and tax system in connection with the uprising. The correspondence of the map of the revolt with the areas with domaines congéables is in his opinion "doubtful". Indeed, it should be noted that municipalities outside the domaines congéables also rose, while other municipalities within the area did not. An abolition of the system was not mentioned in any of the paysan code .

The riot was very often led by women. During this time, royal legislation against women became increasingly strict. All of their economic and civil rights have been weakened. For example, they were no longer allowed to choose their husbands themselves. This was shocking in a country where women traditionally occupy a very important place in society. This deficiency is mentioned in the texts of the Code paysan . After all, Brittany was a Pays d'États , a province with an assembly of estates that was also responsible for tax approvals. The salt tax , the Gabelle , which is widespread in the rest of France , was not levied here and since the unification of Brittany with France, new taxes had to be accepted by the Breton estates. In 1673 the French crown received 2.6 million livres as a voluntary donation (don gratuit) from the Breton clergy . In the same year the estates bought for the same sum the abolition of the Chambre des domaines , which had denied some nobles their legal rights, and they bought themselves free from the royal laws that had introduced the new taxes. With various other expenses in favor of the crown, the payments amounted to an exorbitant sum of 6.3 million livres. Just a year later, the same laws were redefined without negotiating with the estates. In August 1673, Louis XIV had the tax on stamped paper registered by the Parlement of Brittany, and the tax on tobacco in November 1674. This meant a disregard for the “Breton freedoms”, ie those privileges that the Bretons in the treaty of union with France were granted. These new taxes raised fears after the introduction of the table and hit the peasants and the small people in the cities more than the wealthy, because the consumption of tobacco was already widespread among the people, and it was the people who used pewter dishes in contrast to the wealthy. All of this created a broad front of discontent with the unprecedented brutality of the French crown.

course

Urban riots

The uprising began in Bordeaux. The garrisons were too weak for the city's governor, César d'Albret, to restore order. Citizens also refused to set up their militias. From March 26th to 30th, 1675 the city came into the hands of the rebels. On March 29th, the peasants in the vicinity reached Bordeaux to assist the rebels. Under public pressure, the Bordeaux Parliament filed an order to suspend the new tax. The news reached Rennes and Nantes , which also rose in early April. Other cities in the southwest joined the revolt for the same reasons. For example, in Bergerac there was an uprising on May 3rd and 4th. On April 6, the king issued a declaration of amnesty for the rioters in Bordeaux, as his governor did not have the means to bring the city back under control.

In Brittany, the urban uprisings, disorderly and spontaneous, were initially limited to two cities, Rennes and Nantes. The basic pattern of the process was the same there. The government offices of the stamped paper or the marking of the Zinngeschirrs were looted and clashes with the cry of "Vive le roi sans la gabelle" ( German Long live the king without Gabelle! ) Accompanied. A first uprising took place in Rennes on April 3rd, but calm was quickly restored by the King's General Procurator at the Parliament. Another unrest took place on April 18, with at least ten dead, and spread to Saint-Malo the following day . According to Auguste Dupouy, the unrest there was of “minor” magnitude, since the Newfoundland fishermen had left or were ready to leave. This was followed by riots on April 23 in Nantes and again in Rennes and Nantes on May 3. Other cities such as Guingamp , Fougères , Dinan , Morlaix followed.

The citizen militias were not very reliable and at times supported the rebels. Troops were sent to restore calm, first in Nantes on June 3rd, then in Rennes on June 8th. In the Ancien Régime, all troops lived with the residents at their expense, but the Breton cities had the privilege of being exempt from providing shelter for the war people. This violation of the law resulted in an outbreak of anger that lasted for three days, June 9-11. It was expressed in the siege of the episcopal mansion where the governor of Brittany, the Duke of Chaulnes, was staying. This forbade the soldiers to shoot. After the order was given to the troops to leave the city, the situation calmed down. In his letter of June 30, the Duke of Chaulnes expressed his dissatisfaction with the Parliament, which he accused of passivity and benevolence towards the rebels. In his reports, however, he did not mention the extent of the unrest, which was expressed in verbal abuse, the inability to react and the hostage taking of the bishop, who was exchanged for a rebel on May 3. After peasant uprisings in western Brittany became known, a third riot broke out in Rennes on July 17th with a rush to the office of the stamped paper under the low vaults of the Palace of Justice.

Uprising in western Brittany

From June 9th, the example was followed in the cities through actions in lower Brittany. The revolt had several flocks, from the Bay of Douarnenez to Rosporden , Briec and Châteaulin . On June 3rd and 4th the uprising reached the area around Daoulas and Landerneau , on June 6th the area of Carhaix, on June 12th from Brasparts to Callac and Langonnet . A first wave occurred on June 27th and 28th in the area of Le Faouët , for example on the occasion of the Pardon of St. Gurloesius in Lanvénégen . Meanwhile, rumors of the imminent introduction of the Gabelle were spreading in Brittany. The cities did not participate but were attacked. Pontivy was taken on June 21 by 2,000 farmers who scattered or took 400 Mütt with them, handed over by the citizens. The Duke of Chaulnes had to seek refuge in Port-Louis .

On June 23, a group of parishioners rose in the Saint-Tugdual church of Combrit . They looted the manor of the Seigneur of Le Cosquer and mortally wounded him. A little later, the inhabitants of fourteen communities in Bigoudenland began to destroy all the files that deposited the privileges of the seigneurs. The code paysan , which was probably drawn up on July 2nd in the Notre-Dame-de-Tréminou chapel in Plomeur , found its origin in their demands. The peasant uprising broke out in the center of the zone of the domaines congéables , according to Cornette, exactly where the regime was most severe. In a letter to Colbert, the Duke of Chaulnes spoke of the "brutality of the people", but admitted that the seigneurs were a heavy burden on the peasants. The castles and the offices of the stamped paper or the tax on drinks were besieged and looted, the nobles attacked and killed.

In late July and early August 1675, the violence reached its peak in the Poher, where Carhaix and Pontivy were attacked and looted. These cities were not fortified and had no garrison. The farmers in this area were led by the notary Sébastien Le Balp. At the beginning of September he besieged and looted Tymeur Castle with 600 "red hats" and burned all papers and archives there. On the night of September 3, the eve of a planned general uprising, Sébastien Le Balp was killed by a sword blow from his prisoner, the Marquis de Montgaillard . This act put an abrupt end to the revolt.

Code paysan

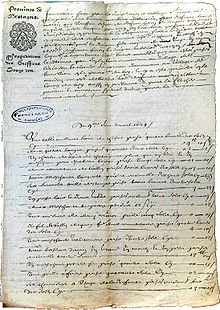

The revolting peasants laid down rules and regulations under different names: code paysan , pessovat ( German that is good ). Eight texts are known which, because of their content, are regarded as anticipations of the Cahiers de Doléances in the French Revolution. The best known is the Règlement des 14 paroisses ( German regulation of the 14 municipalities ). It was probably made in the Notre-Dame-de-Tréminou chapel in Plomeur and appears to follow various earlier texts. It is written in French and committed the residents of 14 parishes. As with royal proclamations, it had to be posted at intersections and read aloud during Sunday sermons. It is divided into fairly short, numbered articles.

Suppression and punishment

All fortified cities ( Concarneau , Pont-l'Abbé , Quimper , Rosporden , Brest, and Guingamp) were equally islands of resistance. Three insurgents, including a woman, were hanged in Guingamp. The “prosecution” began in Nantes, where the royal troops stayed for three weeks and where the ringleader Goulven Salaün, a house servant from lower Brittany, was hanged. Missionaries and Jesuits , above all Julien Maunoir , were mobilized to prevent the farmers from taking any further action. This saves time until the arrival of troops who had devastated the Palatinate under the command of Turenne a year earlier . These arrived at the end of August 1675 and operated in an area from Hennebont to Quimperlé. In Combrit, 14 farmers were hanged from the same oak. The captured leaders were executed after being tortured. This action lasted all of September.

In Aquitaine the arrival and a stay of several weeks for troops were enough to restore calm. In Bordeaux, on November 18, the parliament returned to its decision to suspend taxes. The city was punished for it with the obligation to take eighteen regiments coming from Catalonia during the winter. The officers and soldiers lived with the residents at the expense of the city administration, which could amount to about a million livres. In addition, the Château Trompette was expanded and its garrison strengthened in order to vividly expand the military rule of the king over the city. This included the destruction of the Saint-Croix city gate in the south of the city. Another symbolic measure was the confiscation of the bells of the Saint-Michel and Sainte-Eulalie churches .

The extent of retaliation in Brittany is difficult to quantify. The king ordered the destruction of the contents of all legal archives concerning the uprising. Because of this, this persecution remains the least known of all the great uprisings of the 17th century, and no extensive studies have been conducted. In the name of King Louis XIV, the Duke of Chaulnes ordered heavy sanctions in Bigoudenland. Insurgents were hanged or sent on galleys . The church bells that had rung the storm to mobilize the peasants were brought down, for example at the Notre-Dame de Languivoa chapel in Plonéour-Lanvern . Six bell towers were completely demolished, those of the churches of Saint-Tugdual in Combrit, St-Jacques de Lambour in Pont-l'Abbé, Saint-Honoré in Plogastel-Saint-Germain , Saint-Philibert in Lanvern, Notre-Dame de Languivoa en Plonéour and in Tréguennec . Historians disagree as to whether the last church is today's Notre-Dame-de-Pitié parish church outside the town center or the former parish church that was demolished in the 19th century. Some, like those of Saint-Jacques de Lambour in Pont-l'Abbé or of Saint-Philibert in Lanvern, were never restored by order of the parishes because they saw it as two-tier on the one hand, but on the other hand the memory of the uprising and wanted to see the punishment perpetuated. A tradition that emerged in the 20th century of the tall, cloth-shaped head covering of the female population of Bigoudenland traces the form back to a challenging message sent to the Duke of Chaulnes: “If the king has knocked off the church tower, we will put it on ours Head".

Historians disagree on whether the reprisals were harsh or moderate. For Jean Delumeau, the promise of an amnesty was largely kept. The punitive measures remained moderate and fewer than 80 leaders were brought to justice. The Duke of Chaulnes did not believe in the effectiveness of a brutal prosecution. Many wanted people fled to Paris or Jersey . Alain Croix suspects that the retaliatory measures may have been less violent than desired for fear of isolating the soldiers in the Bocage countryside. Other historians disagree and rely on other sources, such as a letter from the Duke of Chaulnes informing the Governor of Morlaix on August 18 that all the trees on the paths from Quimper towards Quimperlé were beginning to grow under the load that they would have been given, which is also quoted in the conclusions of Yvon Garlan and Claude Nyères. The royal power punished some of the elite but was more ruthless towards the rebellious peasants. The main responsible persons were given to a special commission of the parliament. In exceptional cases, the courts could judge in the last instance, which resulted in the rapid imposition of death sentences. From October 1676 on, galley and death penalties were pronounced against those responsible.

The villages were threatened with collective retaliation to hand over the leaders. On October 12, 1675 Duke of Chaulnes marched 6,000 men into Rennes, as Dragonade among residents quartered were. The Marquise de Sévigné wrote that the duke was received like a king, but for reasons of fear. For a month the city suffered from violence by the troops, and others even set up their winter quarters. The residents of Rue Haute were evicted and a third of the street was demolished. The parliament was exiled to Vannes on October 16, where it remained until 1690 and could only return to Rennes against an extraordinary payment to the king of 500,000 livres. The same thing happened to the Parlement of Bordaux, which was exiled to Condom on November 22nd , then to Marmande and La Réole , and did not return to Bordeaux until 1690. All resistance to absolutism was broken. The Brittany estates accepted a 15% increase in voluntary donations (don gratuit) to the royal treasury and all subsequent financial claims from the government, not to mention the gratuities given by the ministers, particularly to Colbert and his family. Brittany had to pay in full for the maintenance of the troops to put down the uprising, later for an army of 20,000 men during the winter, which the king sent in November 1675 following a complaint from the estates. On February 5, 1676, Louis XIV granted an amnesty (recorded by the Parliament on March 2), along with a list of more than 500 exempted persons.

Comparisons

The dissolution of the uprising was also processed legally. In July 1675, the insurgents of the twenty communities from Scaër to Berrien besieged and looted Le Kergoët Castle in Saint-Hernin near Carhaix. The owner, Le Moyne de Trévigny, Seigneur of Le Kergoët, was believed to be close to those who had introduced taxes on tobacco and stamped paper. A comparison between the communes and Le Moyne de Trévigny was adopted in October 1679 by the estates of Brittany. In August 1675, seven residents of Plomeur were commissioned to negotiate with Monsieur du Haffont about compensation for the looting of his mansion in Plonéour-Lanvern. The settlement resulted in an agreement before the notary. A similar agreement was reached with the people of Treffiagat . In June 1676 the amounts due were halved. The following month, the residents of Plonéour-Lanvern and Plobannalec were asked to deliver eight tons of grain to replace the looted wheat. In 1692, the son of Monsieur du Haffont, who had since died, complained that he had still not received a sou of the compensation payment. Other disputes of this kind dragged on before the courts at least until 1710.

Historical conclusion

The size of the uprising was extraordinary for the reign of Louis XIV. The French historian Alain Croix describes the events as “unprecedented in the context of the time” and “the events that still took place in the time of Louis XIII. were imaginable, have not been since the takeover of power by Louis XIV and remained absolutely unique in the kingdom between Fronde and 1789, with the exception of course the very special case of the camisards in the Cevennes ”. It was the uprising during the reign of Louis XIV in which the local authorities let the rebels do their best. The local peculiarities brought the elite and the people in Brittany closer together. The insurgents initially acted spontaneously, but quickly organized themselves and brought ever larger groups within society to their side. What was unique was that they were not limited to looting, but also took hostages and drafted demands. The French historian Arthur de La Borderie (1827–1901) sees the revolt against the paper tax as a revolt against the tax system and on the occasion of the new taxes. On the other hand, he rejects the statements and remarks made by the Duke of Chaulnes, who reported on the "bad treatment" of the Breton nobles towards the peasants. He explains that the peasants' anger was directed at the nobles for two reasons. For a long time they represented the only power to maintain the existing order in the country, and their castles served as targets in the absence of representatives of the tax authorities. Finally, he returned to certain remarks made in 1675: "the dire passions, the extreme and subversive ideas that necessarily ferment in all these revolting masses, including communism and acts of violence against priests." He was referring to events during the Paris Commune in 1871. "People's passions, freed from social obstacles, plunge into the abyss of barbarism in a single leap". He also quoted the pastor of Plestin: “The peasants believed that everything was allowed, considered all property to be common property and did not even respect their priests. In certain places they wanted to cut off their necks, in others they wanted to expel them from their parishes ”. For Arthur Le Moyne de La Borderie, the uprising of 1675 was also an episode of class struggle .

The Soviet historian Boris Porschnew (1905–1972) essentially worked on the rich archives of the Chancellor of France Pierre Séguier , which were available to him in Leningrad . He, too, describes this uprising as directed against the treasury, as a climax of the class struggle. But it extends the causes of a revolt against the taxes for the landowners (nobles and religious orders). He also presents a Breton patriotic analysis of this survey, citing an article by Nikolai Yakovlevich Marr , which draws a parallel between the situation of Bretons in France and the “allogeneic” Caucasians in Tsarist Russia. Boris Porschnew wrote: “The final incorporation of Brittany into France, which was confirmed by the Brittany estates, took place in 1532. Can we speak of national submission and the struggle for national liberation of the Bretons, given that the Breton nobility were already entirely French and that basically only the peasants remained Breton? The answer lies in the current state of the Breton problem in France. Despite a continuous denationalization of part of the Bretons, the problem remains typical of national minorities and could not be solved under the conditions of a bourgeois order ”. Boris Porschnew draws the conclusion: "We are finding the distant historical roots of this struggle especially in the 17th century". After all, the uprising of 1675 heralded the French Revolution for him.

For Alain Croix, the revolt was the clash between the bourgeoisie and its allies on the one hand and the Ancien Régime on the other, as in the French Revolution, only “on a different scale. The pressure for change is moderate in Brittany and the particularity of the province's situation isolates it from the vast French kingdom anyway. Incidentally, there is nowhere the equivalent to the uprisings of 1675 ”. He also connects the uprising with the differences between the very maritime Breton economy and that in the rest of France, which is more towards the continent.

The French historian Roland Mousnier also emphasizes the archaic Breton feudal system as the cause of the uprising, which he regards as essentially directed against the treasury.

Jean Nicolas mentions the duration of the uprising, the rapprochement between elite and people in lower Brittany and the formulation of precise demands.

Medium and long term effects

The regaining of control silenced the estates and the parliament and also allowed the establishment of the Intendantur of Brittany, the office of royal overseer. Brittany was the last province with this institution, which represented the central power and which the estates of Brittany could always successfully avoid until then. All of Brittany was ruined in 1679 by the military occupation, according to the estates, who caused damage to the towns and villages by their movements.

The insurgent territories in lower Brittany were the same where the "blues" found approval during the French Revolution. They correspond to the areas with the lowest percentage of priestly vocations in the 19th century, the areas of “Breton rural communism” as well as the areas where the Breton language is most vivid. On the fourth Sunday in September, the Notre-Dame-de-Tréminou chapel in Plomeur commemorates this episode of Breton history with a pardon.

The new wave of red hats

In the 1970s, the Red Hats rebellion was portrayed by historians as a stage in the struggle of the Breton people for their emancipation. The Parti communiste français (PCF) organized a festival in Carhaix in 1975 to celebrate the events three hundred years ago. The Democratic Union of Brittany (UDB), for its part, had the play Le Printemps des Bonnets rouges ( German The Spring of the Red Hats) by the Breton writer Paol Keineg played. The performances took place as part of a tour through Brittany with the ensemble of the Parisian Théâtre de la Tempête , which they organized in a tent.

In 2013, protesters in the Finistère department opposed the introduction of the environmental tax on heavy goods vehicles. They wore red hats as a reference to the revolt against the paper tax. The protest became known under the name Mouvement des Bonnets rouges ( German Red Cap Movement ). The demonstrators have announced the color and gathered with red hats on in front of the last control bridge in Finistère, which was already in operation. The rise of the yellow vests movement in 2018 is also seen in a series of a long French tradition of uprisings against increased taxes.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Jean Delumeau: Histoire de la Bretagne . Private, 2000, ISBN 978-2-7089-1704-0 , pp. 292 (French).

- ^ Alain Croix: La Bretagne aux 16e et 17e siècles: la vie, la mort, la foi . Maloine, 1981, ISBN 978-2-224-00681-5 , pp. 283-350 (French).

- ^ Alain Croix, Jean-Yves Veillard: Dictionnaire du patrimoine breton . Apogée, 2001, ISBN 978-2-84398-099-2 , pp. 152 (French).

- ^ Georges-Bernard Depping: Correspondance administrative sous le règne de Louis XIV entre le cabinet du roi . tape 1 . Imprimerie nationale, 1850, p. 498 (French, google.de [accessed April 1, 2020]).

- ↑ Herrieu Loeiz: Istoér Breih, pé Hanes he Vretoned . Dihunamb en Oriant, 1910, p. 248 (Breton).

- ↑ Yvon Garlan, Claude Nibres: Les Révoltés Bretonnes de 1675 . Editions sociales, 1975, p. 26-27 (French).

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 229 .

- ^ Jean Nicolas: La rébellion française: mouvements populaires et conscience sociale, 1661–1789 . 2002, p. 254 .

- ^ Jean Meyer, Roger Dupuy: Bonnets rouges et blancs bonnets . In: Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l'Ouest, Volume 82, Number 4 . 1975, p. 405-426 (French, persee.fr [accessed April 1, 2020]).

- ↑ James B. Collins: La Bretagne dans l'État royal . 2006, p. 308 .

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 606 .

- ↑ James B. Collins: La Bretagne dans l'État royal . 2006, p. 242 .

- ↑ Skol Vreizh: Histoire de la Bretagne et des pays celtiques . tape 3 , p. 104 (French).

- ^ Alain Croix: L'Âge d'or de la Bretagne, 1532–1675 . 1993, p. 521 .

- ↑ James B. Collins: La Bretagne dans l'État royal . 2006, p. 180 (and in the texts of the Code Paysan ).

- ↑ Skol Vreizh: Histoire de la Bretagne et des pays celtiques . tape 3 , p. 104 (French).

- ^ A b Charles Durand: La révolte du papier timbré advenue à Bergerac en 1675 . In: Bulletin de la société historique et archéologique du Périgord . tape XXI , 1894, p. 389–393 (French, bnf.fr [accessed April 1, 2020]).

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 607 .

- ↑ Jean Delumeau: Histoire de la Bretagne . 2000, p. 291 .

- ↑ Auguste Dupouy: Histoire de Bretagne . Éditions Boivin, Paris 1932, p. 262 (French, newly published in 1983 by Éditions Calligrammes, Quimper, and Éditions Ar Morenn, Le Guilvinec).

- ↑ Herrieu Loeiz: Istoér Breih, pé Hanes he Vretoned . 1910, p. 249 .

- ↑ a b Olivier Chaline: Le règne de Louis XIV . Flammarion, 2005, ISBN 978-2-08-210518-7 , pp. 323-324 (French).

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 609 .

- ↑ Auguste Dupouy: Histoire de Bretagne . 1932, p. 265 .

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 612-613 .

- ↑ Jean Nicolas: La Rébellion française: mouvements populaires et conscience sociale, 1661-1789 . 2002, p. 256 .

- ↑ Yvon Garlan, Claude Nyères: Les Révoltés bretonnes: Rebellions urbaines et rurales au XVIIe siècle . 2004, p. 70-78 .

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 615-616 .

- ^ Arthur Le Moyne de La Borderie: La révolte du papier timbré advenue en Bretagne in 1675 . In: Les Bonnets rouges . Union Générale d'Éditions, Paris 1975.

- ↑ Skol Vreizh: Histoire de la Bretagne et des pays celtiques . tape 3 , p. 110 .

- ↑ Jules Lépicier: Archives historiques du département de la Gironde, tome 41 ( fr ) Société des archives historiques de la Gironde. P. 256, 1906. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ↑ James B. Collins: La Bretagne dans l'État royal . 2006, p. 249-250 .

- ↑ Serge Duigou, Jean Michel Le Boulanger: Histoire du Pays bigouden . Editions Palantines, Plomelin 2002, ISBN 978-2-911434-23-5 , pp. 74 (French).

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 621 .

- ↑ Olivier Chaline: Le règne de Louis XIV . 2005, p. 325 .

- ^ A b Alain Croix, Jean-Yves Veillard: Dictionnaire du patrimoine breton . 2001, p. 153 .

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 622 .

- ↑ Yvon Garlan, Claude Nyères: Les Révoltés bretonnes: Rebellions urbaines et rurales au XVIIe siècle . 2004.

- ↑ Armand Puillandre: Sébastien Le Balp - Bonnets rouges et paper timbré . Keltia Graphic, Kan an Douar 1996, ISBN 978-2-906992-65-8 , p. 87-89 (French).

- ^ Arthur Le Moyne de La Borderie: La révolte du papier timbré advenue en Bretagne in 1675 . In: Les Bonnets rouges . 1975, p. 155, 161 .

- ↑ Olivier Chaline: Le règne de Louis XIV . 2005, p. 321 .

- ↑ Jean Quéniart: La Bretagne au XVIIIe siècle (1675-1789) . Ouest-France, 2004, ISBN 978-2-7373-1818-4 , pp. 19 (French).

- ^ List of those excluded from the amnesty

- ↑ Serge Duigou: La révolte the bonnets rouges en pays bigouden . Ressac, Quimper 1989, ISBN 978-2-904966-19-4 (French).

- ^ Alain Croix: L'Âge d'or de la Bretagne, 1532–1675 . 1993, p. 522 .

- ↑ a b Olivier Chaline: Le règne de Louis XIV . 2005, p. 326 .

- ^ A b Jean Nicolas: La rébellion française: mouvements populaires et conscience sociale, 1661–1789 . 2002, p. 257 .

- ^ Arthur Le Moyne de La Borderie: La révolte du papier timbré advenue en Bretagne in 1675 . In: Les Bonnets rouges . 1975.

- ↑ a b Boris Porschnew: Les buts et les revendications des paysans lors de la révolte bretonne de 1675 . In: Les Bonnets rouges . Union Générale d'Éditions, Paris 1975.

- ^ Alain Croix: L'Âge d'or de la Bretagne, 1532–1675 . 1993, p. 536 .

- ^ Alain Croix: L'Âge d'or de la Bretagne, 1532–1675 . 1993, p. 533 .

- ↑ Roland Mousnier: Fureurs paysannes: les paysans dans les révoltes du XVIIe siècle (France, Russie, Chine) . Calmann-Levy, Paris 1967.

- ↑ Jean Quéniart: La Bretagne au XVIIIe siècle (1675 to 1789) . 2004, p. 19 et seq .

- ↑ James B. Collins: La Bretagne dans l'État royal . 2006, p. 240 .

- ↑ Ronan Le Coadic: Campagnes rouges de Bretagne . Skol Vreizh, 1991, ISBN 978-2-903313-40-1 , pp. 4 et seq . (French).

- ^ Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons . tape 1 , 2005, p. 604 .

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Monnier: Histoire de l'Union démocratique bretonne . In: Les cahiers du Peuple breton . tape 7 . Presses populaires de Bretagne, Lannion 1998, pp. 19 (French).

- ↑ L'Ecotaxe cristallise les tensions en Bretagne où la révolte gronde ( fr ) L'OBS. October 27, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- ^ Jean-Claude Bourbon: Violentes manifestations en Bretagne contre l'écotaxe ( fr ) Bayard press. October 26, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- ↑ La fronde contre les impôts, une longue tradition française ( fr ) Le Figaro . November 16, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

literature

- Jean Bérenger: La révolte des Bonnets rouges et l'opinion internationale . In: Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'Ouest . tape LXXXII , no. 4 , 1975, p. 443-458 (French).

- Léon de la Brière: Madame de Sévigné en Bretagne . Éditions Hachette, Paris 1882 (French).

- Serge Duigou: La Révolte des Bonnets rouges en pays bigouden . Éditions Ressac, Quimper 1989 (French).

- Serge Duigou: Les Coiffes de la révolte . Éditions Ressac, Quimper 1997 (French).

- Serge Duigou: La Révolte des pêcheurs bigoudens sous Louis XIV . Éditions Ressac, Quimper 2006 (French).

- Yvon Garlan, Claude Nières: Les Révoltes bretonnes de 1675 . Éditions Sociales, Paris 1975 (French).

- Loeiz Herrieu et al .: Istoér Breih pe Hanes ar Vretoned . Dihunamb, Lorient 1910, p. 247-250 (Breton).

- Charles Le Goffic: Les Bonnets rouges . Editions des régionalismes, 2013, ISBN 978-2-8240-0150-0 (French).

- Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie: Révoltes et contestations dans la France rurale de 1675 à 1789 . In: Revue des Annales . No. 1 , 1974 (French).

- Jean Lemoine: La révolte dite du papier timbré, ou, Des bonnets rouges en Bretagne en 1675 . H. Champion, Paris 1898 (French).

- Jean Meyer, Roger Dupuy: Bonnets rouges et blancs bonnets . In: Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'Ouest . tape 82 , 1975 (French).

- Upper: Istor Breizh betek . 1790 (Breton).

- Armand Puillandre, Sébastien Le Balp: Bonnets rouges et papier timbré . Éditions Keltia Graphic, Kan an Douar 1996 (French).

- Roland Mousnier: Fureurs paysannes: les paysans dans les révoltes du XVIIe siècle (France, Russie, Chine) . Calmann-Levy, Paris 1967 (French).

- Jean Nicolas: La rébellion française: mouvements populaires et conscience sociale, 1661–1789 . 1st edition. Gallimard, 2002, ISBN 978-2-7028-6949-9 , pp. 254 (French).

Theater adaptations

- Le Printemps des Bonnets rouges by Paol Keineg (1972).

- Les Bonnets rouges, chronique d'hier et d'après by Gérard Auffret (1971). The first performance with the ensemble of Les Tréteaux d'Armor took place on July 10, 1971 in Landerneau on the market square.