German minority in Denmark

The German minority in North Schleswig , also known as the German ethnic group or German North Schleswig , consists of around 15,000 to 20,000 people in North Schleswig (also South Jutland or Sønderjylland ) in Denmark . This corresponds to about six to nine percent of the area's population or 0.2-0.3 percent of the entire Danish population.

German minority in North Schleswig

Identity and designation

Publications by the minority themselves often prefer the term German ethnic group as a term for the minority. In official and general Danish usage, the designation det tyske mindretal (i Sønderjylland) ("the German minority (in Southern Jutland )") applies similarly to det danske mindretal (i Sydslesvig) for the Danish minority south of the border. "Minority" is also the term used in the Bonn-Copenhagen declarations.

On the part of the Danish majority population, the relatives are also called "German-minded" (Danish: tysksindet ) or "Heimdeutsche" (hjemmetyskere) . The latter word comes from the period after 1864 and originally referred to the native German-minded people of Schleswig, in contrast to the Prussian officials and soldiers who only settled after 1864. Sometimes it is perceived as negative, although it is considered by many to be a traditional and everyday name. Since the decades after 1864, and at the latest since 1920, the Danish inhabitants have rarely referred to themselves as Nordschleswiger, but as Süderjüten (Danish: sønderjyder ) and the part of the country as Süderjutland ( Sønderjylland ) .

According to the Bonn-Copenhagen Declarations of 1955, the commitment to a national minority is free and must not be checked. Danish censuses do not provide any information on ethnicity. The core of the minority can be found in the Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger, in the Schleswig Party and its voters as well as in the people who visit German institutions such as kindergartens, schools and libraries.

For decades there has been a clear effort by the minority to put an end to the border struggle of earlier times and to replace nationalism with European values and cultural "two-streams". The region is strongly emphasized, and many members of the minority, but also parts of the Danish population, describe themselves as Schleswig rather than German or Danish. As in southern Schleswig, there is a certain influx of the majority population into the schools, who use the minority schools as an alternative cultural and educational offer.

language

In the German north of Schleswig, the language use is characterized by diglossia , a bilingual or multilingualism, whereby the different languages are used in different situations. The colloquial language is primarily the Danish dialect Sønderjysk (Synnejysk) , which is still used in everyday life by almost two thirds, mainly by the elderly of the ethnic group. High German is the language of schools, although Danish is also taught and cultivated as a second language. The newspaper Der Nordschleswiger and the minority organizations use the German language.

Standard German is also the standard language on official occasions (church services, festivals and clubs). Ecclesiastically, this applies both in the North Schleswig community , the church of the rural areas , which is organized as a separate religious community , and in the four northern Schleswig towns, where the service is performed by German-speaking pastors within the Danish national church ( Danish Folkekirken ). These two solutions for the German members of the Evangelical Church in the countryside and in the cities have proven themselves since the reunification of North Schleswig with Denmark in 1920. Catholicism hardly plays a role in this part of the country.

Against this background, membership of the ethnic group ("national ethos") can usually not be determined on the basis of everyday language. Especially in the border areas on both sides of the border, the South Jutian Danish dialect was considered the neutral language of the entire population until the 1950s; however, today's language border practically coincides with the state border. On the Danish side, too, South Jutian has lost ground, although it is one of the stronger dialect areas in Denmark. Promotion work is carried out both by the German minority and in other circles. In the Æ Synnejysk Forening cultural association , German and Danish-minded people work closely together, which - in comparison with the traditionally nationally separated youth associations, gymnastics associations and church associations - represents an innovation.

Low German was never widely used, as the importance of Low German had already declined when a certain Germanization of North Schleswig took place from the 17th century through the use of High German as the de facto official language. The Nordschleswiger has now and then a crevice on the north Schleswig flat .

Organizations

Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein

The Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger (BDN) is the umbrella organization of the German minority and represents them externally in all questions. With around 4,500 members, it is the largest association and the publisher of the daily newspaper Der Nordschleswiger (circulation: 4,000). Despite criminal prosecution and other adverse circumstances, a new political beginning succeeded in 1945 with the establishment of the Federation on November 22, 1945, whose principles were formulated in November 1943 by a group of opponents of the National Socialist occupation regime in Hadersleben. The principles, combined with a declaration of loyalty to Denmark, drew a line under the border revision claims of the German minority - both were expressed in the founding declaration of the BDN.

His main task in the first post-war years was the attempt to alleviate the consequences of legal accounting; however, no concessions were made from the Danish side. After most of the German prisoners were released, association structures could slowly be rebuilt from 1948 onwards. The highest body of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein is the Assembly of Delegates. This elects the main chairman, his deputy and the chairmen of the culture committee and the Schleswig Party (SP). While the culture committee is responsible for the overall cultural planning of the minority, the Schleswig party takes on the political representation of the minority in the municipalities.

Press

- The Nordschleswiger , daily newspaper of the ethnic group

schools

The German School and Language Association for North Schleswig is the amalgamation of local school and kindergarten associations that are themselves responsible for their facilities, in particular of

- 22 German kindergartens with 600 children,

- 14 German schools, including 5 secondary schools, with 1400 students,

- the German Gymnasium in Aabenraa.

In addition, there is the Deutsche Nachschule Tingleff , a boarding school for the 9th to 10th grade, which accepts students from all over Denmark and Northern Germany.

In addition to the general education of the children, the aim of the lessons is in particular to introduce them to the German language and culture. The school leaving certificate is recognized in both Denmark and Germany. The number of pupils in Denmark has generally declined in recent years, which also applies to German schools.

The German schools are considered to be private schools or free schools ( friskoler ), which operate on the basis of the Danish Free School Act and mainly receive funding as a result. Unlike other Danish private schools that collect school fees, school is free, except for membership in the school association, a small activity fee, class trips and bus transport.

It happens that Danish parents send their children to a German school because - similar to the Danish schools in southern Schleswig - the minority schools are small, well-equipped schools with bilingualism and a good educational environment.

Libraries

- The Association of German Libraries in North Schleswig operates a central library and central library in Aabenraa, four city libraries in Hadersleben, Sonderburg, Tondern and Tingleff and serves 15 school libraries with block collections. Two book buses drive every 5 weeks to rural areas and deliver reading material and AV media free of charge. The libraries have a media inventory of 230,000 media units and record around 350,000 loans per year. The library system works within the framework of the Danish Library Act, which makes the provision of public libraries a compulsory task for the municipalities. A school library law applies to schools.

Youth work

The German Youth Association for North Schleswig is the umbrella organization for 25 youth groups, sports clubs and youth and leisure clubs with a total of around 2500 members, organizes sporting and cultural events as well as trips and camps and operates the Knivsberg youth farm with its extracurricular activities and a holiday home on the Flensburg Fjord . The youth association is also the organizer of the Knivsbergfest, a summer folk festival of the German North Schleswig-Holstein, the tradition of which goes back to 1894. There is also the German Rowing Association with seven local rowing clubs, the citizens' and craftsmen's associations, the shooting clubs, the North Schleswig Comradeship Association and the local history study group.

Social work

- Social work is in the hands of the Nordschleswig Social Service Association, an association of 20 nursing associations, women's associations and senior clubs with 2560 members. The tasks of the association had to adapt to the welfare state development in Denmark, so that the nursing service was dropped and the emphasis was shifted to social care and family counseling, for example in the Quickborn house on the Flensburg Fjord. Special attention is given to the elderly, who are able to enjoy spa stays, excursions and trips.

Agriculture

The German farmers are organized in the Main Agricultural Association for North Schleswig. It looks after the economic and professional interests of around 1100 members and deals with crop cultivation, livestock husbandry and accounting. It is an independent group member of the Danish Farmers' Association.

church

In the four municipalities of Aabenraa , Hadersleben , Sonderburg and Tondern , the Danish national church has appointed its own pastors for the German-speaking part of the entire community since 1920, as a need for German-speaking church supplies and a long tradition of German-speaking church services were recognized here. This was only partially the case in rural areas, which is why members of the minority founded the North Schleswig community in Tingleff in 1923 , a free church under Danish law. It was affiliated with the Schleswig-Holstein regional church (today: Evangelical Lutheran Church in Northern Germany ). There were up to seven parishes, each looked after by a pastor, today there are five. Of the nine pastors, eight come from the Federal Republic of Germany and only one from the minority, 99 percent of whom are denominationally Protestant.

politics

The Schleswig Party ( Slesvigsk Parti ), as part of the BDN, represents the interests of the German minority, but has an independent board.

National level

1920–1939 the minority was represented in the Folketing by Pastor Johannes Schmidt-Vodder , who was replaced by Jens Møller in 1939–43 . In 1943, the minority did not take part in the Folketing election, mainly because 7,500 people were absent due to military activities, which meant that the number of voters would halve and the mandate would be lost.

Also in 1945 the minority did not take part in the Folketing election. From 1947 to 1953 the minority put forward non-party candidates. With the Danish Basic Law of 1953 and the expansion of the Folketing from 150 to 179 members, the Schleswig party again succeeded in gaining a mandate. As a minority privilege, the party did not and does not have a threshold clause (otherwise the rule 1953-61 was at least 60,000 votes nationwide and from 1961 two percent of the vote). 1953-64 represented Hans Schmidt-Oxbüll the party.

In the 1950s and 1960s, schools, kindergartens and libraries were set up with the support of the Federal Republic of Germany and the State of Schleswig-Holstein. For complex reasons, such as the industrial development with emigration from the rural areas, but perhaps also the end of the border war, there was a weakening of the minority in the 1950s to 1980s, as was the case with the Danish minority south of the border. Since the electorate had decreased, the party last took part in a Folketing election in 1971.

In 1965, the Folketing appointed a contact committee with representatives of all parties in parliament, to which the ethnic group was allowed to send three members. Since the committee had little competence or importance, the German minority tried to be represented by a candidacy on the list of Centrum Democrats . 1973–79, Jes Schmidt, the editor-in-chief of the German daily newspaper Der Nordschleswiger , was a member of the Folketing. The cooperation ended after the death of Jes Schmidt, because Centrum-Demokratie [Democratic Center] rejected a new candidate because of his past in the Waffen SS.

Even today, political representation in parliament and government is practiced by the contact committee for the German minority ( Kontaktudvalget for det tyske Mindretal ). The members of the contact committee are three representatives of the minority, proposed by the political organization of the minority and formally appointed by the Danish interior minister, as well as the head of the secretariat of the German ethnic group in Copenhagen (Jan Diedrichsen), a representative of each faction of the Folketing, the interior ministers and the Minister of Education.

Local and regional level

Before 1970, the minority in the small parish- based parishes had 46 representatives. During the municipal reform in 1970, the four North Schleswig districts were merged in Sønderjyllands Amt . (The districts of Åbenrå and Sønderborg were merged in 1932–1970, but still had separate district representatives.) After 1970, the Schleswig party had about one representative in the North Schleswig District Council and 16 members in 8 of the 23 large municipalities.

With the new structural reform that came into effect in 2007, the 14 Danish offices (districts) were dissolved and the municipalities were merged into larger units. The four northern Schleswig municipalities now roughly correspond to the four districts before 1970 (Tondern, Aabenraa, Hadersleben and Sønderborg).

Initially after the structural reform, the SP was represented by two MPs in Aabenraa and Tondern , and one MP each in Sønderborg / Sonderburg and Hadersleben / Haderslev . In Hadersleben, a fully valid mandate could only be obtained in the 2009 election.

In 2017, the SP achieved 13.5% and five members in Sønderborg, due to the popularity of Stephan Kleinschmidt and a list connection with the radical Venstre and the conservative Folkeparti , both of which were not represented. In Aabenraa the SP has 6.1% and two mandates, in Tondern 5.8% and two mandates, in Hadersleben 2.2% and one mandate (a fully valid mandate that was achieved through the list connection with Kristdemokraterne and Retsforbundet ).

In addition to the possibility of obtaining a fully valid mandate, the Danish local electoral law has provided since 2005, in order to safeguard the protection of minorities, to grant a special mandate without voting rights if the party of the German minority receives a quarter of the votes in a mandate. In the first period of the new large community of Hadersleben, the representative of the Schleswig party held such a mandate. If the party of the German minority receives less than a quarter but more than a tenth of the votes in a mandate, the party will not receive a special mandate, but the municipality must set up a contact committee for the German minority. The latter rule has not yet been applied. Since the four North Schleswig local councils each have 31 members, the proportion of votes for a mandate is around 3.2%, for a special mandate for the minority 0.8% and for representation via a contact committee 0.32%. The background to this regulation is the European framework convention for the protection of national minorities , but laws on the representation of the Hungarian minority in Slovakia were specifically studied.

The special regulation does not apply to regional representation elections. After the structural reform of 2006, North Schleswig is part of the Syddanmark region. Denmark is divided into five regions, which do not represent a full administrative level, but are to be understood as a delegation of the central power. Its tasks are primarily hospitals, but also regional spatial planning, psychiatry, offers for the severely disabled, as well as development plans for nature, the environment, teaching and culture, the practical implementation of which is the responsibility of the municipalities.

Many people from North Schleswig and the German minority criticized the abandonment of the historically conditioned administrative unit of North Schleswig (Sønderjyllands Amt). In later years, however, there is a fear that the regions will be abolished, as the Syddanmark region has meanwhile advocated cross-border cooperation.

The partnership Region Sønderjylland-Schleswig , founded in 1997, consists of the four North Schleswig municipalities and Region Syddanmark, on the German side the districts of North Friesland and Schleswig-Flensburg and the city of Flensburg (but not the district of Rendsburg-Eckernförde), as well as the state of Schleswig-Holstein and the two minorities.

Economy

The German private schools can be classified relatively easily under the Danish free school laws, according to which 82% of the costs are covered by the state. The remaining costs are paid for by a special notice to cover the two-part mother tongue tuition, in principle according to rules that also apply to immigrants and foreigners, so that German schools are in practice completely on an equal footing with municipal schools.

In other areas, too, there is some financial aid from the Danish state , in particular for the library system, one third of which is funded by the Danish state and 2/3 by the German state . The German minority receives further subsidies from the Federal Republic of Germany and the State of Schleswig-Holstein .

history

The Duchy of Schleswig emerged as an independent state structure in the 12th century, but until 1864 it belonged to the Danish crown as a royal Danish fief and through a personal union . It comprised the area between the Königsau in the north and the Eider in the south. Already since 1460 there were close relations with the German Duchy of Holstein , which also had the Danish king as head through a personal union. See also: Duchy of Schleswig

Danish and Prussian times

The Duchy of Schleswig was formed after 1200 from the Jarltum of Southern Jutland and three southern Jutland Sysseln . It remained a Danish imperial and royal fief until 1864, but was at times divided into several domains. The Gottorf ducal house , which also had shares in northern Schleswig, had a formative influence in the 17th century . The colloquial language in northern Schleswig was dominated by Danish or the dialectal Sønderjysk, while (standard) German became increasingly important in southern Schleswig. In modern times, German was also used as the administrative language in North Schleswig; the duchies were accordingly administered jointly in German by the German Chancellery in Copenhagen. With the introduction of the Reformation , Latin was replaced by Danish in most of the districts of North Schleswig. However, urban communities, such as in Sonderburg , Hadersleben (1526) and Tondern (1531), received German as the church language . The boundary between the German and Danish church language was later to become the boundary of ethos, as it ran roughly along the current state border. Economically, Schleswig was oriented more towards the south and formed a unit with Holstein.

With the emergence of national currents around 1830, there were serious disputes between Germans and Danes in the duchies, which mainly related to the future national affiliation of Schleswig. Both a Schleswig-Holstein (German) and a Danish national liberal movement emerged, both of which stood in opposition to the absolute Danish ruled as a whole . The majority in Holstein and in the south of Schleswig acknowledged their German nationality. With regard to social stratification, the German creed was especially widespread among the upper and middle classes, for example among civil servants, merchants, pastors, the urban bourgeoisie and large farmers, and not least among Duke Christian August von Augustenburg and his son Friedrich , who were united Schleswig-Holstein strived for in the German Confederation with itself as constitutional ruler. The Danish creed, on the other hand, was more widespread among the rural population, but also in parts of the urban bourgeoisie. Although numerically dominant in their areas, the languages Danish and Frisian were often considered socially inferior. Accordingly, southern areas such as Eiderstedt and Schwansen switched to Low German before 1800. In the course of the 19th century - after the outbreak of the conscious nationality struggle - fishing followed, but in central southern Schleswig, where social conditions were more balanced, Danish was spoken until the 20th century.

The national dissent finally erupted for the first time in 1848. A draft of a moderate-liberal constitution for the state as a whole, suggested by King Christian VIII , was published on January 28, 1848 by his successor Frederick VII . He did not meet the demands of the Danish National Liberals for a national constitution only for Denmark and Schleswig. Nevertheless, German national liberals in the duchies feared just such a step. On March 18, 1848, at a joint meeting in Rendsburg , the German delegates of the Schleswig and Holstein assemblies of estates demanded, among other things, the admission of Schleswig to the German Confederation , freedom of the press and assembly and a popular arming. On March 20th, the demands also reached the capital Copenhagen, where on March 20th a people's assembly initiated by the Danish National Liberals took place in the Copenhagen casino. Under public pressure, the King dismissed the previous government on March 21 and on the following day appointed a government (the so-called March Ministry ), which was jointly occupied by Danish Conservatives (general supporters of the state) and Danish National Liberals (representatives of the Eider Police ). The demands made by the German MPs in Rendsburg were rejected by Friedrich VII on March 23, 1848, which in turn led to the formation of a German-minded Provisional Government and finally to the Schleswig-Holstein uprising in Kiel on the night of March 23 to 24, 1848 led. The survey ended, however, with the defeat of the German Schleswig-Holsteiners and a restoration of the status quo of the previous state as a whole.

From 1851 to 1864 Denmark made a policy change in the Duchy of Schleswig. Danish circles now generally perceived that a language change was spreading from the south, and it was often the opinion that too little had been done to prevent this Germanization or to enforce the equality of languages. In order to save the future of Danish in central Schleswig, the controversial language scripts were introduced, according to which the school language in parishes with Danish vernacular should continue to be Danish, the church language German and Danish with changing services. A more extensive rescript by King Friedrich VI. von 1810 had planned that the court language should also follow the vernacular, but was stopped by reluctant officials from the German Chancellery. It is unclear whether the 1851 rescripts also included peripheral areas where the language change was so advanced that the Danish language was gone. Although Danish pastors and teachers were able to report educational advantages in teaching the new school language among Danish-speaking children, the change was politically accepted by the German Schleswigholsteiners in the course of the civil war.

Although the Danish government refrained from directly punishing the officials and pastors who had supported the insurgent government in the 1848-50 war for treason, they were often dismissed or required to swear allegiance to the Danish king. Theodor Storm's example was about the latter, but after refusing to make this statement, he lost his legal qualifications. Then he moved to Prussia to work there.

The language rescripts and the exchange of disloyal officials were seen by the Schleswig-Holstein movement as an attempt at "Danization". Protests spread among the population of Schleswig, especially in the German-oriented middle and upper classes. The protest soon spread to the newspapers of all German states. The Danish "tyranny" in Schleswig and Holstein became a collection symbol for all of German nationalism.

The picture was complicated by the fact that only Denmark proper had a free constitution since 1849. In 1858, the German Confederation refused to allow a general Danish state constitution to apply in Holstein, which was also endangered for Schleswig, as Denmark had undertaken to treat the two duchies equally in their connection to the kingdom. Accordingly, absolutism still ruled Holstein; Both duchies had privileged voting rights; freedom of expression and freedom of the press was worse than in Denmark, but better than in most German states.

Ultimately, it became apparent that public opinion in southern Schleswig continued to cling to the German and in northern Schleswig predominantly to the Danish creed. The Danish November constitution of 1863 provided for the establishment of joint bodies for Denmark and Schleswig, but with the retention of Schleswig's self-government (including a state parliament for Schleswig). The German Confederation demanded the immediate repeal of the constitution and decided a federal execution against the member state Holstein. Against protests by the German Confederation, however, Prussian and Austrian troops crossed the border river Eider in February 1864, which set the German-Danish and Second Schleswig War in motion. As a result of the war, Denmark had to cede all of the duchies to Prussia and Austria ; In 1867, Schleswig was finally united with Holstein to form the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein .

Just as the Danish state failed to show a convincing tolerance for minorities before 1864, the Prussian state increased its Germanization measures in the predominantly Danish north of Schleswig after 1864 . In 1876, German was allowed as the sole administrative language in Schleswig, and in 1888 German finally became the only school language, with the exception of four hours of religion in Danish. In the same year the Prussian authorities closed the last Danish private school. German settlers were also deliberately recruited. After 1896 the Prussian state bought land and set up state-owned domain farms that were leased to German settlers. However, these measures met with resistance from the Danish population in Schleswig and led to the organization of the Danish minority in northern and central Schleswig, which not least pushed for the referendum promised in the Prague peace treaty to be held. The policy of Germanization reached its climax with the appearance of Oberpräsident Ernst Matthias von Köller and the Köller policy named after him, which openly discriminated against the Danish part of the population. By 1900 around 60,000 Danish Schleswig emigrants, not least because of the Prussian military service, others were expelled by the Prussian authorities. Around 5,000 Danish Schleswig-Holstein soldiers died as German soldiers in the First World War . Parts of the southern Schleswig population, especially the Frisians, decided to emigrate during the Prussian period.

1920 to 1922

With reference to the right of peoples to self-determination proclaimed by the American President Wilson and Article V of the Prague Peace of 1866, which provided for a referendum in Schleswig, a referendum was held in northern Schleswig after the First World War in 1920 .

The boundaries of the voting areas were determined by the Allies, as were the voting modalities, which to a certain extent favored Denmark. In the vote in the 1st zone (North Schleswig), the overall result of the area was decisive ("en bloc vote"), while in the 2nd zone, votes were taken on a community basis. Denmark was given the opportunity to win individual municipalities with a Danish majority in the 2nd zone, should Danish majorities arise here - but without the risk of losing individual municipalities with a German majority in the 1st zone.

The historian Hans Victor Clausen had proposed the so-called Clausen line as the border line as early as 1891, taking into account the historical, linguistic and economic conditions , which coincided with the border between the 1st and 2nd voting zone, and thus with today's border. This line also roughly corresponded to the historical boundary between the Danish and German church languages. While Danish (South Jutish) was and is also spoken south of this line, knowledge of the standard Danish language was not very widespread. Clausen had only defined his line up to about 7 kilometers west of Flensburg and did not comment on Flensburg's position. Flensburg was generally seen as part of North Schleswig, as it still had a Danish majority in the first decades after 1864. The fact that industrialization and militarization had led to Germanization during the Prussian period spoke against the integration of Flensburg in Denmark. It is also assumed that the four cities of North Schleswig wanted to get rid of the competition from the large Flensburg. The right-wing national camp in Denmark, however, hoped that the former Danish sympathies in Flensburg were still strong. The policy of the Danish Nordschleswiger, as well as the Danish government, was therefore a reunification up to the Clausen line without Flensburg. Only right-wing national circles advocated the effort to win more southern areas for Denmark - which the more moderate majority considered impossible or dangerous, as it would jeopardize relations in the border region and with its German neighbors.

The en-bloc procedure in the 1st zone was also supported by the view that was widespread among the victorious powers and in Denmark that Schleswig was subjected to Germanization after 1864 with coercion or pressure or immigration from the south (and migration to the north), and this To a certain extent they wanted to compensate for development. Equally decisive, however, were the desire to keep North Schleswig together economically, and a short border line that was as easy to defend and control as possible.

A third voting zone, which was supposed to extend as far as the Tönning – Schleswig – Schlei line, was surprisingly decreed by the Allies, which probably happened at the instigation of national groups in Denmark and Danish activists in southern Schleswig. However, the Danish government asked the Allied Committee to delete this zone again.

The result of the approximately 100,000 eligible voters in North Schleswig was 74.9% for joining Denmark and 25.1% for remaining with the German Reich. A majority of all cities voted to remain with Germany; the rural population, however, largely voted for Denmark. In addition to German strongholds with three-quarter majorities such as the city of Tondern and the Flecken Hoyer (76% and 73%) and narrow majorities of 54% in Aabenraa and 55% in Sønderborg , there were also majorities in some communities in the south in favor of remaining with Germany. The southern and eastern hinterland of Tønder in particular was controversial and mostly had narrow German or Danish majorities.

The 2nd zone almost completely voted for Germany, with the exception of three municipalities with a majority Danish vote, which remained with Germany because they were not directly on the new border line.

After the vote in the second voting zone, the German historian Johannes Tiedje suggested that some predominantly German or almost predominantly Danish areas of the district of Tondern Germany be added. Then the Tondern district would not have had to be divided, and minorities of equal numbers would have arisen on both sides of the new border. Denmark rejected this suggestion, as did the demand from Danish national circles to claim Flensburg despite the vote. In the subsequent demarcation process, the German majorities near the border in southern North Schleswig were not taken into account. The current state border thus runs along the Scheidebach in the east and the Wiedau in the west, and around 25,500 German-minded people remained immediately north of the border, and around 12,800 Danish-minded people south of the border. See also: Referendum in North Schleswig, 1920

The area around Hoyer, Tondern, Tingleff and Krusau, which was disputed in 1920, has since formed a core area of the German minority, while the German presence in the northern half of the region, on the west coast and on the island of Alsen is low (with the exception of the cities).

1922 to 1933

The German minority had to adjust to life in the Danish "hostel state". After the founding of the Schleswig voters' association in 1920, oppositions to the Danish state immediately arose because the demarcation of the border was felt to be unjust and a border revision was called for.

On the one hand, despite their negative attitude towards Denmark, the German minority was still given the opportunity to lead a cultural life of its own, which was the toleration of German associations and daily newspapers, the development of a German school system with German language of instruction in public and private schools, the continuation or establishment of kindergartens, the establishment of a German library system and the continued existence of (reduced) German-speaking church life.

On the other hand, Danish nationalist circles made no secret of the fact that they wanted to assimilate the German ethnic group as quickly as possible. The North Schleswig politician HP Hansen said that in a few years the German minority would disappear like dew in the sun. Corresponding measures were also taken: after German and Danish had been equal as the church language for centuries, only Danish was introduced as the official church language in 1923. In the same year, immigration from the south was prevented and German citizens were expelled through the introduction of residence and work permits, while immigration from so-called Reich Denmark and Danish institutions such as adult education centers, barracks and state-owned companies were strongly promoted and a national settlement policy was pursued in agriculture .

A “national struggle” broke out over the people who had not taken a position nationally, and over their agricultural land, because both ethnic groups still had their strengths largely in the independent peasantry. Both sides set up credit institutes to support them. In this "ground fight" between 1925 and 1939 about 34,000 hectares were transferred from German to Danish hands; During the difficult economic times, factors such as trade unions and the Danish workplace also played a role in the political recruitment of people who did not want to commit themselves nationally, so that many German-minded social democrats became members of the Danish social democratic party and were more likely to be active here.

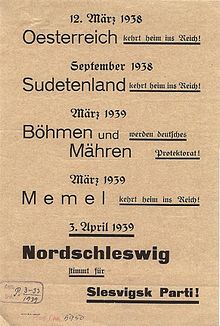

1933 to 1945

The financial and cultural dependency of the minority on the German Reich became clear after the National Socialist takeover of power in 1933. Crisis- related social conflicts since the 1920s, especially in agriculture , and the border struggle had prepared a good breeding ground for National Socialism among the German people of North Schleswig, as with other ethnic Germans . As early as 1933, many of them voluntarily joined National Socialism. In 1938, all German-Southern Jutland associations " into line ". The party of the German Nordschleswiger, the Schleswigsche Party (SP), which had a seat in the Danish parliament since 1920, joined the German NSDAP in 1935 and was renamed NSDAP-N . Jens Möller was the “ ethnic group leader ” . The region was also a stronghold of the Danish DNSAP , which competed with the German National Socialists. A border revision was demanded by the German minority throughout the interwar period, but the demand increased after 1933 and especially after Hitler's annexations of the Sudetenland and Memelland.

War effort

When the Third Reich occupied Denmark on April 9, 1940 at the Weser Exercise Company, in violation of international law and in breach of a non-aggression pact, the troops were enthusiastically welcomed by members of the German minority with the Hitler salute. Many collaborated openly with the Wehrmacht right from the start. See also: Denmark under German occupation

More than 2100 young Germans from North Schleswig volunteered in the war for Germany, of which 748 were killed. Most of them served in the Waffen SS because of their Danish citizenship . It was only from 1943 onwards that it was possible to volunteer for the Navy and Air Force .

Even after the gradual turn of the war after Stalingrad, the voluntary work of the German minority did not decrease. From the end of 1944 to 1945, volunteers from the German minority were involved in building three lines of defense across Jutland, the Brunhilde, Gudrun and Kreimhilde positions.

There was no open opposition within the minority; however, the question of the future in the event of a German defeat was taken up by a very small group of non-National Socialists. The so-called Hadersleben Circle secretly drafted the Hadersleben Declaration in November 1943 , which proclaimed the end of the border struggle and loyalty to the Danish royal family , to Danish democracy and to the German-Danish border that had existed since 1920, but still demanded cultural autonomy for the German ethnic group.

When a new main association for the minority, the Bund deutscher Nordschleswiger (BdN), was founded on November 22nd, 1945 , the contents of the Hadersleben declaration served as a solemn declaration of loyalty to Denmark. However, the statement did not take a position on the recent crimes and the settlement of war criminals and collaborators, which was actually the hottest issue of the time.

1945 to 1955

On May 5, 1945, the German troops surrendered in Denmark. In the near future there was a dispute with Danish collaborators, including many members of the German minority. A large number of male members of the minority were initially interned, and many were later convicted. Historians have debated whether this was an example of collective guilt , however the criminal proceedings in the legal settlement were conducted at the individual level.

The anger of the Danish population, and especially of the resistance fighters, was partially released on the ethnic group. The house of the German daily newspaper and the enormous Bismarck tower of the German meeting place on the Knivsberg were blown up. There were isolated attacks by Danish groups or people against German shops and meeting houses, as well as by Germans against Danish police stations. The only fatality fell when on December 28, 1948 a drunk man fired shots at a German Christmas party in Lügumkloster , killing a woman. The perpetrator was a native of Flensburg, who was a Danish resistance fighter in Copenhagen and was arrested by the German Wehrmacht in 1943.

About 3,500 members of the ethnic group were arrested, mostly in the Fårhus camp, the renaming of the former internment camp Frøslev , which was an instrument of the German Wehrmacht against Danes during the war. Later, 2,948 of them were sentenced to prison terms of one to ten years under laws with retroactive effect (so-called legal accounting ). Most received two years' imprisonment, while the NS ethnic group leadership received significantly higher sentences. Almost every German family in North Schleswig was affected by the so-called legal settlement, especially the war volunteers.

The German occupation troops left a debt of eight billion Danish kroner with the Danish National Bank . At the request of the Allies, a Danish law confiscating German and Japanese property was adopted. German property, including that of private individuals, was initially registered and confiscated, but ultimately only confiscated when it came to German citizens, German companies or capital or German imperial property. The private schools of the German minority were closed in 1945, but some have reopened since 1946. The confiscation of German property also applied outside of North Schleswig and also affected property of Danish-minded or non-National Socialist German citizens, e.g. B. Members of the Danish minority in southern Schleswig. 90 German farmers became the victims of the dissolution of the Vogelgesang loan as tenants of farms .

German nationals who were a minority among the German ethnic group were mostly expelled from Denmark. These "emigrants" were initially found in the former Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg, which was run by the British occupation authorities.

The liberal regulations of the pre-war years were repealed in 1945. A school law allowed the establishment of private schools at primary school level, but without exam rights for schools. Because punished teachers had been banned from their profession (or, if they were German citizens , had to leave the country) and the buildings of the minority were confiscated by the Danish state, the lack of teachers and buildings made teaching almost impossible. The re-establishment of the "German School and Language Association for North Schleswig" as the sponsor of a German school system in autumn 1945 was able to ensure that a very modest amount of German lessons was offered in an elementary school. Gradually by the early 1950s, 13 of the expropriated school buildings were bought back. The approximately 5,000 children in German schools and kindergartens at the end of the war had to be integrated into Danish schools by then.

Since 1955

In 1955 the Bonn-Copenhagen Declarations fully recognized the minorities in Germany and Denmark and confirmed their rights; The declarations did not grant the minorities any special rights, but only guaranteed the free admission of nationality and equal treatment of all citizens: According to the declarations, the minorities are citizens with equal rights in the respective “hostel state” and the minority issues affecting them are their internal affairs.

For the German minority, however, the results of the negotiations in 1955 were a disappointment, despite the tolerance towards the respective minority guaranteed in the Bonn and Copenhagen declarations; for their demand for amnesty and return of the expropriated property were viewed by the Danish side as interference in domestic Danish affairs and rejected. The German minority at least got the exam rights back for their schools and was allowed to set up a grammar school in Aabenraa .

After all, this started a process of relaxation that has led to today's good neighborly relationship. From 1953 to 1964 the minority was represented with its own mandate in the Folketing, and from 1973 to 1979 through an electoral alliance with the Center Democrats. After that, independent representation was no longer possible. A contact committee with parliament and government was established. In 1983 the secretariat of the German ethnic group was set up in Copenhagen. The historical highlights included the visit of Queen Margrethe II on July 24, 1986, the visit of Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker on April 27, 1989 as well as the joint visit of Queen Margrethe II and Federal President Roman Herzog on July 2, 1998 to the German ethnic group in North Schleswig. These visits were important steps on the way to final recognition and cultural equality and an expression of good neighborliness in the border region. Another breakthrough in the relationship between minority and majority came in 1995 with the invitation to the chairman of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein, Hans Heinrich Hansen , to the Düppel festival on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the demarcation of the border in 1920, on which he was next to the Danish Queen and the Danish Minister of State as a speaker. The minority viewed this as an expression of the equality of the German North Schleswig-Holstein.

Today, the German ethnic group is recognized as the only minority in the Kingdom of Denmark with its linguistic and cultural peculiarities in accordance with the Framework Convention of the Council of Europe for the Protection of National Minorities and the Charter for the Protection of Regional and Minority Languages.

Well-known German North Schleswig-Holstein

Leading representatives and officials

- Johannes Schmidt-Wodder , pastor, leading representative of the German minority and member of the Danish Folketing (parliament)

- Waldemar Reuter , general practitioner, leading representative of the German minority and, after 1945, as chairman, played a key role in the reconstruction of the school system and the church in North Schleswig.

- Matthias Hansen , executive chairman of the Association of German North Schleswig-Holstein 1945–1947

- Niels Wernich , chief chairman of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein 1947–1951

- Hans Schmidt-Oxbüll Chairman of the Association of German North Schleswig-Holstein 1951–1960, member of the Danish Folketing 1953–1964

- Harro Marquardsen , Chairman of the Association of German North Schleswig-Holstein 1960–1975

- Gerhard Schmidt , main chairman of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein 1975–1993

- Hans Heinrich Hansen , main chairman of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein 1993–2006, president of the Federal Union of European Nationalities since 2007

- Hinrich Jürgensen , Chairman of the Association of German North Schleswig-Holstein since 2006

- Ernst Siegfried Hansen , Secretary General of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein from 1945–1947

- Jes Schmidt , editor-in-chief of Der Nordschleswiger , general secretary of the Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger from 1947–1951, member of the Danish Folketing 1973–1979

- Rudolf Stehr , General Secretary of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein from 1951–1973

- Peter Iver Johannsen , General Secretary of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein from 1973 to 2008

- Uwe Jessen , Secretary General of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein since 2009

- Hermann Heil , General Manager of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein from 1962 to 2002

- Rasmus Hansen , General Manager of the Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein since 2002

- Siegfried Matlok , former editor-in-chief of Nordschleswigers , head of the secretariat of the German minority at the government and the Folketing in Copenhagen 1983-2006.

- Jan Diedrichsen , Head of the Secretariat of the German Minority at the Government and Folketing in Copenhagen from 2006, Director of the Federal Union of European Nationalities , (FUEN)

- Gwyn Nissen , editor-in-chief of Nordschleswigers

Artist and writer

- Anton Nissen , painter and graphic artist

- August Wilckens , painter and graphic artist

- Emil Nolde , painter and graphic artist

- Arndt Georg Nissen , painter and graphic artist

- Charlotte Hasselmann , painter

- Niko Wöhlk , painter

- Peter Sandkamm-Möller , painter

- Heinrich Hecht (Aabenraa) , painter

- Andreas Petersen-Röm , painter

- Thomas Hansen-Brunde , painter

- Gottfried Kinze , painter and ceramist

- Hans Schmidt-Gorsblock , local poet and writer

- Harboe Kardel , editor-in-chief and writer

- Hans Peter Johannsen , library director and writer

- Hans Schmidt Petersen , author and writer

- Günter Weitling , evangelical theologian; Church historian and writer

- Andrea Kunsemüller , journalist and writer

- Nis-Edwin List-Petersen , composer of New Sacred Songs , writer and library director

Well-known German Nordschleswiger who worked in Germany

- Jens Peter Jessen , political scientist and economist, resistance fighter in the assassination attempt on July 20, 1944

- Theodor Kaftan , theologian and general superintendent for Schleswig from 1886–1917

- Hjalmar Schacht , from 1923 to 1930 and 1933 to 1939 President of the Reichsbank and from 1934 to 1937 also Reich Minister of Economics

See also

- Danish minority in Germany

- Germans in Copenhagen

- German-speaking minorities

- Federal Union of European Nationalities

literature

- Society for threatened peoples: Danes and Germans as minorities.

- Gerd Stolz, Günter Weitling (Ed.): North Schleswig - Landscape, People, Culture. Husum 2005, ISBN 3-89876-197-5 .

Web links

- Federation of German North Schleswig-Holstein

- 100 years of the German minority . Representation of the minority policy of the North Schleswig-Holstein on the homepage of the “Federation of North Schleswig-Holstein” since the referendum in 1920

- printed daily newspaper Der Nordschleswiger , whose abolition is planned. Instead, there should be a fortnightly online magazine from 2021.

- German school and language association

- German libraries in Denmark

- German Youth Association North Schleswig

- Social Service North Schleswig

- North Schleswig community

- Schleswig party

- Hans Heinrich Hansen: The German minority in North Schleswig and Europe. Speech 2008 reproduced on the website of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (In particular about the protection of minority rights in the reform of the South Jutland region and the creation of the larger region of Syddanmark ( Memento of December 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Nordschleswigsche Gemeinde , kirche.dk

- ^ School profile , German School Aabenraa

- ↑ Contact budget for det tyske Mindretal , Leksikon, graenseforeningen.dk

- ^ Haderslev Domsogn, The German part of the community

- ↑ Tønder Sogn og Kirke, The German part of the municipality ( Memento from March 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (web archive, accessed on May 29, 2019)

- ↑ http://www.geschichte-sh.de/nordschleswig-1840-1920 Nordschleswig 1840 to 1920 on the homepage of the Society for Schleswig-Holstein History

- ↑ Jacob Munkholm Jensen: Dengang jeg drog af sted - Danske immigranter i the amerikanske borgerkrig. Copenhagen 2012, pp. 46/47.

- ↑ Henning Madsen: Mørkets gys, Frihedens lys. Copenhagen 2014, p. 221.

- ↑ BDN abolishes daily newspaper. The North Schleswig June 19, 2018

- ↑ Our digital future. Nordschleswiger will be published fortnightly after February 2021 .