Don Karlos (Schiller)

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Don Carlos, Infante of Spain |

| Genus: | A dramatic poem |

| Original language: | German |

| Author: | Friedrich Schiller |

| Publishing year: | 1787 |

| Premiere: | August 29, 1787 |

| Place of premiere: | Theater im Opernhof Gänsemarkt , Hamburg |

| people | |

|

|

Don Karlos, Infante of Spain (also known as Dom Karlos at the time ) is a drama by Friedrich Schiller . The piece, identified in the paratext as a “ dramatic poem ”, consists of five acts . Schiller wrote the drama between 1783 and 1787; it was premiered on August 29, 1787 in Hamburg. It primarily deals with political and social conflicts - such as the beginning of the Eighty Years War , in which the Dutch provinces won their independence from Spain - and family-social intrigues at the court of King Philip II (1556–1598).

In addition to the title of the national edition, "Don Karlos", the drama is also often quoted and treated as Don Carlos .

action

The Spanish Crown Prince Don Karlos meets his childhood friend Marquis von Posa again in the summer residence of Aranjuez , who has been traveling for a long time and has just returned from Brussels, where he has now become a member of the Dutch provinces. He wants to convince Karlos to have himself sent to the troubled province of Flanders as governor, in order to give the Protestant Dutch, who are revolting against the Catholic Spanish occupation power, greater freedoms and so peacefully resolve the conflict.

Karlos, however, no longer wants to hear about his political dreams as a young man and desperately tells his friend that he still loves Elisabeth von Valois , his former fiancée, but who has now become the wife of his father, King Philip , and thus Karlos' stepmother. Desperate, Karlos Posa explains that the strict etiquette of the court on the one hand and the suspicious jealousy of the king on the other have not yet allowed him to speak to the queen in private. Posa, who had also been friends with Elisabeth since his time in Paris, then arranged a meeting between Karlos and the Queen, during which Karlos confessed his passion to his stepmother. Elisabeth, however, is appalled by Karlos' impetuous wooing, admits that she got to know and honored Philipp as a human being, and emphasizes her sense of duty and responsibility for the Spanish people. She decisively rejects Karlos' advances and calls on him to no longer devote himself to love for her, but instead to love his fatherland.

Back in Madrid, Karlos asks the king, just as Posas intended, for governorship in Flanders, although to do so he has to jump over his shadow and overcome his aversions to the imperious, unloved father. But King Philip does not trust the Infante and refuses his offer of reconciliation. He considers him too careless, soft, even cowardly, and prefers the more experienced Duke of Alba for the post .

Karlos receives a love letter from Princess Eboli , but mistakenly believes that the queen is the author. So overjoyed he follows the invitation contained therein to go to a remote cabinet of the castle, but only finds Eboli there, who confesses her love to him in complete misunderstanding of the true situation. Karlos learns from a letter from Philip to Eboli that she is to be made the king's mistress and therefore forced to marry the Count of Silva. Karlos is moved by her story, but can only offer her his friendship, not his love, because, as Karlos confesses to the princess on his part, he loves someone else. He takes the compromising letter with the intention of delivering it to the Queen later. Only now does Princess Eboli begin to suspect who is hiding behind that other love. Out of jealousy and because of her rejection by the prince, she decides to take revenge on Karlos and the queen.

Duke Alba and Father Domingo have meanwhile allied themselves against Karlos. They convince the Eboli to betray Karlos' love for the queen to her husband and ask them to steal incriminating documents from the queen. Karlos tells Posa of his misfortune towards the Eboli and of the king's infidelity. Posa prevents the prince from showing the king's letter to Eboli to the queen and reminds him of his former ideals and political goals.

After Alba reveals the meeting between Queen and Karlos to the king and Domingo tells him about a confession by Princess Eboli and rumors that Elisabeth's little daughter is not the king's child, the already suspicious Philip feels betrayed by his wife and decides To have his wife and son killed. Surrounded only by cowardly court envelopes, he longs for a sincere friend and comes up with the idea of summoning the Marquis of Posa, who is known as fearless and worldly, and accepting him into his service. Posa initially rejects the king's request. He makes a fiery plea for humanity and appeals to Philip to turn prison Spain into a refuge of freedom. The king is impressed by Posa's courage and openness and makes him his minister and closest advisor. Above all, however, he now sees him as a trusted friend who is supposed to spy on the true relationship between Karlos and the Queen. Posa makes an appearance.

Original steel engraving from Raab after Ramberg , around 1859

He seeks out Elisabeth and arranges to meet with her to persuade Karlos to rebel against the king and secretly go to Brussels to free the Dutch from the Spanish yoke. He brings Karlos a letter from the Queen and asks for his wallet. The queen has meanwhile discovered the theft of her letters (by the Eboli) and accuses the king, which leads to a dispute. The Marquis hands Karlos' wallet to the King. When Philip discovers Eboli's letter to his son in it, he gives the marquis unrestricted authority to act and issues an arrest warrant for the Infante. Count Lerma reports this to Karlos, who then runs, dismayed, to Princess Eboli, in whom he mistakenly sees his last confidante. There Posa arrests him. The princess now confesses to the queen that the letters have been stolen. Posa realizes that his original plan has failed, secretly takes a new one and asks the queen to remind the king's son of his old vow to create a free state.

The Marquis visits Karlos in prison and informs him about the false letters that compromise him (Posa) and that he has leaked to the king. Duke Alba comes and declares Karlos free, but he sends Alba away because he only wants to be rehabilitated personally by the king and to receive his freedom again. Posa tells Karlos of the Eboli betrayal and reveals to him his new plan to sacrifice himself for his friend. A short time later a shot is fired and the marquis sinks to the ground, fatally hit. The king, resigned and bitterly disappointed by Posa's betrayal, appears to release his son. But he accuses him of murder and informs him about his friendship with the Marquis. An officer of the bodyguard reports on a revolt by the citizens in the city who want to see Karlos free. Lerma persuades the heir to the throne to flee to Brussels. The Grand Inquisitor, however, shows the king his human weakness as a mistake and demands Karlos as a sacrifice. Meanwhile, disguised as his grandfather's ghost, he has snuck into the queen's room. There Philip delivers him to the Grand Inquisitor.

To understand

Historical reference

In the period from 1479 to 1492 a unified Spanish state was established under the government and administration of the Catholic kings Isabella I (Castile) and Ferdinand II (Aragón) (as Ferdinand V, King of the united Spanish monarchy). After Ferdinand's death in 1516, his grandson Charles I, who also ruled the Burgundian Netherlands as Duke of Burgundy , ascended the throne. After Karl was elected Roman-German King in 1519 , he took on the title of “chosen emperor” at his coronation in 1520 and ruled as Charles V over the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . Under him, Spain rose to become a world power. It included most of the Pyrenees Peninsula (except Portugal), Sicily, Sardinia and the Kingdom of Naples, as well as the countries of the so-called Burgundian Heritage. After the war of Spain against the French King Francis I , Milan and a number of northern Italian regions were added.

When Charles V resigned as emperor and king of Spain, his son Philip II ruled over Spain, parts of Italy, the overseas territories and the Spanish Netherlands from 1556 onwards . The Dutch aristocrats protested against the introduction of the Inquisition and the increase in dioceses because this limited their own power. The iconoclasm of 1566 caused a punitive expedition to be sent under the Duke of Alba (1567–1573). It was not until 1648 that the armed conflicts ended with the recognition of the northern part of the Spanish Netherlands as an independent republic of the States General .

The capture and death of Don Carlos inspired Schiller. The fact that Schiller depicts Alba’s posting to Flanders and the greeting of the Duke of Medina Sidonia after the fall of the Armada in his drama at the same time (in fact, there were 20 years between the two events), can be recognized (as well as other changes, which some as Misunderstanding of history ) that it was not Schiller's intention to write a realistic drama.

History of origin

Schiller received his first reference to the subject from Wolfgang Heribert von Dalberg , who pointed out to him that the Abbé Saint-Réal ( Dom Carlos, nouvelle histoire ) was being edited . On July 15, 1782 Schiller wrote to him: "The story of the Spaniard Don Carlos deserves the brush of a playwright and is perhaps one of the next subjects that I will work on." On December 9, 1782, he asked his friend, the librarian Wilhelm Friedrich Hermann for a number of books, including the Œuvres de Monsieur l'Abbé Saint-Réal . On March 27, 1783, Schiller wrote to Reinwald that he was now determined to tackle Don Karlos: “I think [...] is based on more unity and interest than I previously believed, and that I have the opportunity to strengthen myself Drawings and harrowing or touching situations. The character of a fiery, great and sensitive youth , who is at the same time the heir of several crowns, - a queen who, through the compulsion of her feelings, perishes with all the advantages of her fate, - a jealous father and husband, - a cruel hypocritical inquisitor and barbaric duke von Alba etc. shouldn't, I think, fail […] there is also the fact that there is a shortage of such German plays that deal with great state figures - and the Mannheim theater wants me to deal with this subject. ”To implement the subject Schiller needed additional material and asked for more works in the letter, such as Brantome's story Philipp ІІ. Schiller also studied the History of Phillip ІІ. by the Englishman Watson and the Historia de España by the Spaniard Ferreras.

The first phase of work lasted from the end of March to mid-April 1783. This is where the so-called “Bauerbach draft” was created, an outline of the plot clearly structured in five acts. During this time, Schiller thought intensively about the figure of the title hero, whereupon he wrote to Reinwald on April 14, 1783: “We create a character when we mix our feelings and our historical knowledge of foreigners into a different mixture [...]. Because I can definitely feel a great character without being able to create it. But that would be proven true that a great poet must at least have the strength for the highest friendship, even if he has not always expressed it. The poet does not have to be the painter of his heroes - he has to be his girl whose bosom friend [...] Carlos has, if I can use the measure, the soul of Shakespeare's Hamlet - blood and nerves of Leisewitz Julius and the pulse of me [... ]. ”In this letter, Schiller expresses for the first time the intention to integrate a polemical tendency into his play.

At the end of July 1783, Schiller moved to Mannheim and was employed as a theater poet on September 1st. Only a year later did he resume work on “Don Karlos”. On August 24, 1784, he confessed to Dalberg in a letter, “Carlos is a wonderful subject, excellent for me. Four great characters, almost of the same size, Carlos, Philip, the Queen and Alba, open an infinite field for me. I can't forgive myself now that I was so stubborn, maybe also so vain, to shine on an opposite side, to want to fence my imagination into the barriers of bourgeois Kothurn [...] I'm glad that I'm like that now am quite a master of the iambics. It cannot be missing that the verse will give my Carlos a lot of dignity and shine. "

According to Streicher's information, Schiller was already up to the in July 1784. Act advanced. On December 26, 1784, Schiller wore the І. Duke Karl August before. Schiller then founded a magazine, the first issue of which appeared in March 1785 with the title "Rheinische Thalia". It consisted only of contributions by the poet, including the nine appearances from those of the І. Act existed. Schiller lived in Gohlis near Leipzig until September 11, 1785 and came there with the ІІ. Act ahead. However, he achieved his most intensive progress in Dresden or Loschwitz , where he wrote on it in Christian Gottfried Körner's summer residence , possibly also in Schillerhäuschen . The second booklet, published under the title “Thalia”, contained the first three appearances of the ІІ. Act. The third issue (April 1786) ended with the sixteenth, currently last appearance of the ІІ. Act.

In the spring of 1787 Schiller completed his drama in Tharandt . At the same time he created stage work and completed the print manuscript for the book edition. He shortened the І act by almost a thousand verses by also reducing and smoothing expressions. On October 12, 1786 Schiller wrote to the Hamburg theater director Schröder that his “Don Karlos” would be finished by the end of the year and that this play was capable of a theatrical performance. Schröder wanted a summary in iambs and received a theatrical adaptation of 3,942 verses. A stage version in prose, the so-called "Riga prose version" was created in April 1787.

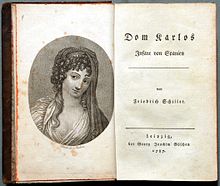

At the end of June 1787 the first book edition was available under the title "Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien, by Friedrich Schiller, Leipzig, bei Göschen, 1787". An improved second edition also appeared in 1787. Further editions, including a superb edition in large octaves, were published by Göschen until 1804. The last edition edited by Schiller appeared in 1805 in the first volume of the Cottas collection "Theater von Schiller" under the title "Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien, Ein dramatisches Gedicht". Schiller deleted 78 lines there, made a number of detailed changes and left everyone Start verse with a capital letter.

The Marquis of Posa as Schiller's mouthpiece?

Although caution is always required to infer the author's views too quickly of any literary figure, in the central tenth appearance of the third act, the one-to-one conversation between the Marquis of Posa and King Philip, Schiller's own should quite clearly be The convictions of these years on some key political issues can be expressed in words:

The king immediately suspects that the marquis is a "Protestant", but the latter rejects it. He is a "citizen of those who will come", so actually a figure of the late 18th century, thus Schiller's present. He has nothing in mind with democracy or a bourgeois revolution; because: "The ridiculous anger | The novelty that only the chains burden | Which it cannot completely break, enlarges, | Will never heat my blood ”. He dreams of a time in which "civil happiness [...] will then walk reconciled with the greatness of a prince". Philip should become “one king of millions of kings”. All he has to do is give his subjects “freedom of thought”.

However, the marquis is depicted in various scenes in such a way that it is not always clear whether his behavior is completely error-free. This applies above all to his little intrigues and pretenses such as B. to Philip and even to his friend Karlos, which he, just like the rest of court society, uses as a means to an end to achieve his goals - no matter how altruistic they are. It is true that he embodies the author's political ideals best, but when it comes to the emotional side, Schiller's heart beats at least as much for the much more naive Don Karlos. After all, according to Schiller's aesthetic ideal, understanding and feeling belong together.

Don Karlos and his father, both tragic heroes?

King Philip is shown at Schiller not only as the cold-hearted autocrat, sees the Karlos in him and he also is; he acts at least to a comparable extent as a victim of the court society, frozen in its conventions, which seeks to preserve what is traditional at any price and solely for the sake of power (including the Catholic Church). At the dramatic turn ( peripetia ) of the plot, in the middle of the third act, Philip is alone and looking for a “person”. In this he is similar to many tragic heroes of antiquity, e.g. B. Creon and Oedipus (brother and father of Antigone ).

This means that Philipp is in the same situation as, according to Schiller, the theater-goers themselves, up to and including the prince. In his treatise The Schaubühne regarded as a moral institution, Schiller writes that the audience in the theater should be confronted with the "truth" in a way that reaches their hearts. For princes in particular, the theater is often the only medium through which the “truth” can reach them: “Here only the greats of the world hear what they never or rarely hear - truth; what they never or seldom see, they see here - the people. ”The Marquis von Posa is an instrument through which this intention of Schiller is implemented.

The king, as a victim of the political system he represents (namely, unenlightened, tyrannical absolutism ), should ultimately convert to " enlightened absolutism " and become a "good prince" by introducing freedom of thought in his country; see. also Immanuel Kant's demand in his book What is Enlightenment? : Sapere aude! "Have the courage to use your own understanding (...)!" In addition to personal courage, Schiller also calls for the political framework conditions (indirectly via Posa) in order to be able to and do this.

Further topics and motifs

Schiller's drama Don Karlos takes up some of the conventions and motifs typical of Schiller himself:

- In the conflict between the character of the title hero and his father, King Philipp, Schiller processed the motif of the generation conflict, which he already included in his youthful works The Robbers and Cabal and Love : The representatives of two different age groups symbolize the replacement of an old, outdated social system with a new one .

- Another level of conflict can be seen in Karlos' vacillations between personal inclination (enthusiastic love for Elisabeth) and political duty (intervening in the Dutch war of liberation), a topic that is repeatedly the subject of dramatic literature (see e.g. Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra or Grillparzer's The Jewess of Toledo ).

- The isolation of the absolute ruler is a well-known motive, see z. As Shakespeare's historical drama Henry V .

- References can be made to Schiller's work on the aesthetic education of man .

Formal and linguistic aspects

For modern readers it is striking, but typical of the classical drama, that the "moment" triggering the "Schaubühne as a moral institution" is not explicitly mentioned in Schiller's list of characters: the Spanish people on the one hand and the citizens of Flanders on the other, whose urge for freedom the establishes a central, above all politically ambitious friendship between Karlos and Posa and sets the further action in motion.

The dramatic design

With Don Karlos , Schiller orients himself more than in his earlier plays, such as the robbers , to the dramaturgical demands of Aristotelian poetics as received in the 18th century. The unity of place and time is less given than that of the action and the fulfillment of the class clause :

- "Don Karlos" is set in at least two different locations: Aranjuez and Madrid, there in different rooms, buildings etc. (castle, prison etc.).

- The duration of the action in "Don Karlos" is about 5 days. So Don Karlos exceeded the time regulation typical of the time. In the strict traditional sense, the plot of a drama should be completed in 24 hours (which e.g. is still fulfilled in the cabal and love ). Nevertheless, one can assume a uniform time here insofar as there are no large time leaps of several weeks, months or even years.

- The unity of the plot is clearly given in "Don Karlos". Scenes like the Eboli plot could also exist for themselves, but they are not separated from the linear course of the plot, but come together. The action pushes purposefully towards the end in a continuous tension curve .

- The heroic characters of an Aristotelian tragedy, however tragic and therefore flawed, always represent people of high class (whereas in comedies middle and lower classes can also have important roles). Similarly, all the people who are significant in "Don Karlos" either come from the royal family or are nobles. Bad characters like Domingo or Alba are also socially high. However, this does not contradict Aristotle's theory of drama and was not unusual in Schiller's time either (compare, for example, Caesar, who is depicted negatively in character in Gottsched's Dying Cato ).

The entire work is written in a five-part, rhymeless iambic form (the so-called blank verse ). This linguistically bound style is typical of what is known as “closed” dramas in Volker Klotz's typology , while “open” text forms are often written in prose .

In the tectonics of the play, too, Schiller follows the model of a classical, closed dramaturgy, as it was later used in literature and music. Theater scholar Freytag has reconstructed:

- Act 1 (exposition): The Prince's fateful love. Renewed commitment of the prince to the ideal of freedom and political commitment.

- Act 2 (exciting moment): Karlos' relapse and the difficulties it created (the enmity of Eboli and Duke Alba). At the end of the act, Karlos is brought to his senses by Posa's intervention.

- 3rd act (climax): The apparent possibility of an understanding between the absolutist monarch and the champion of freedom.

- 4th act (retarding moment): reversal of the plot through the intrigue created in the 2nd act and the Posas action that became necessary as a result, up to the failure of Posas and the triumph of the court party at the end of the act.

- 5th act (catastrophe): Karlos' failure in reality at the moment of inner perfection.

The observance of strict formal aspects on the one hand and the thematization of the striving for freedom on the other hand place the drama on the border between Sturm und Drang and Weimar classical music .

Reception history

Interpretation as a historical key piece

Verdi (possibly already Schiller) placed parts of the opera in Fontainebleau, which served the kings and emperors as a country residence for several French epochs. Possibly this is an allusion to Philip VI. (from the House of Valois ) and Johanna von Burgund as well as son Johann II. (France) with his wife Jutta von Luxemburg , whose two wives died around the year 1348 of the plague. As a result, the father took the son's fiancée as his wife. At the same time war raged against England, but it was settled. Furthermore, the father died only a short time later at the age of 57. Old age is given as the cause of death.

Settings

The most famous setting is Giuseppe Verdi's Don Carlos from 1867. The Russian-German composer Alfred Schnittke was commissioned in 1975 in the Soviet Union to write the incidental music for Don Karlos. The production at Moscow's Mossoviet Theater was to take place in a sacred setting. Officially to capture the gloomy mood of the Spanish Inquisition, but also to honor his late mother, he composed a modern requiem with a creed , which was a provocation in the Soviet composers' association. The world premiere took place in Budapest in 1977 .

Reiner Bredemeyer composed a radio play music in 1966 (Director: Martin Flörchinger ).

Text output

- Friedrich Schiller: Dom Karlos, Infante of Spain. Göschen, Leipzig 1787. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Friedrich Schiller: Don Karlos, Infante of Spain. Leipzig: Göschen 1802. Digitized at Google

- Lieselotte Blumenthal, Benno von der Wiese (ed.): Schiller's works. National edition . Volume 7, Part I: Paul Böckmann, Gerhard Kluge, Gerhard (eds.): Don Karlos. Infant of Spain . Last edition 1805. Weimar 1974.

- Kiermeier-Debre, Joseph (Hrsg.): Friedrich Schiller - Dom Karlos , original text with appendix on author, work and text form, including chronological table and glossary, published in the library of first editions, 2nd edition 2004, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich. ISBN 978-3-423-02636-9

- Schiller, Friedrich: Don Karlos . Text, comment and materials, edit by Michael Hofmann and Marina Mertens. Oldenbourg, Munich, 2012, ISBN 978-3-637-01535-7 .

Secondary literature

- Erika Fischer-Lichte: "Brief history of the German theater" (p. 373, 4.3.1. Problems of a performance history. Using the example of Don Carlos). Tubingen; Basel: Francke Verlag cop. (1993).

- Jan CL König: "Give freedom of thought: The speech of Marquis Posa in Friedrich Schiller's Don Carlos ". In: Jan CL König: About the power of speech. Strategies of political eloquence in literature and everyday life. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht unipress (2011), pp. 268–295. ISBN 3-8997-1862-3 .

- Matthias Luserke-Jaqui : Friedrich Schiller . Francke, Tübingen, Basel (2005), pp. 135–169. ISBN 3-7720-3368-7 .

- Hartmut Reinhardt: Don Karlos . In: Schiller-Handbuch, ed. by Helmut Koopmann. 2nd, revised and updated edition. Stuttgart: Kröner 2011 [1. Ed. 1998], pp. 399-415. ISBN 978-3-534-24548-2 .

- Claudia Stockinger: The reader as a friend. Schiller's media experiment "Dom Carlos". In: Zeitschrift für Germanistik 16/3 (2006), pp. 482–503.

See also

Web links

- Don Carlos at Zeno.org .

- Don Carlos in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Don Carlos as a free and public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hamburger Abendblatt, May 7, 1955, Don Carlos premiered at Gänsemarkt

- ↑ Open and closed drama. A diagram based on Volker Klotz ( Memento from May 4, 2007 in the Internet Archive )