Fish in ancient Egypt

Fish , seafood and other aquatic animals were among the most important foods in ancient Egypt and have been the most important source of proteins for a large part of the Egyptian population since early history . Written and archaeological sources provide extensive information on various fish and other aquatic animals, as well as their catch and use. Aquatic animals were depicted in ancient Egyptian art , used as medicine, clam shells and snail shells worked and used as jewelry or tools or used in a religious context . Fishing was a separate branch of industry, water animals were traded and the hunt for fish and other water animals was a pastime of the Egyptian elite . The Bible also emphasizes the importance of fish as a food in ancient Egypt.

fishes

In contrast to other Mediterranean cultures of antiquity , the Egyptians mostly caught freshwater fish , and in the Nile Delta also brackish water fish . According to the current source situation, the catch of saltwater fish played no role. The reasons for this are unclear, it may have been unnecessary to expose oneself to the greater risk of deep-sea fishing, and easier to fish in the Nile and the oasis waters. In addition to the entire Nile and its delta, the main fishing areas were the waters in the Fayyum Basin .

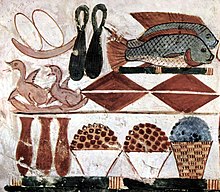

More than 65 Nile fish have been described in modern times. About 30 of them have been proven for ancient Egypt thanks to archaeological sources , as they were passed down as images in graves. For about half of these identified fish, their ancient Egyptian names are also known. Various types of fish had several names; In total, around 50 different ancient Egyptian fish names are known today. Some images from this time of the Old Kingdom are so outstanding that the fish species can be scientifically clearly identified. This is rarely possible for later phases of Egyptian history. Individual species are then more difficult to distinguish, but the genus or at least the family of the depicted animals can often be identified. The Egyptians apparently already had knowledge of the habits of some fish species, for example, on several murals, the whiskered catfish swimming on their backs and mullets in swarms were depicted. From written records, not only the names of the individual fish, but also the names of body parts and organs are known.

Important fish were:

- Mullets . These were most often depicted on murals. Even today they are still among the most important fish caught in the Nile. They were valued above all for their firm and tasty meat and were fished with draw nets. The roe was processed by salting, pressing and drying into a caviar-like , quite valuable product.

- Perch fish were the second most frequently depicted. Above all, cichlids and the Nile cichlid , which can reach a length of 60 centimeters, are shown. The latter was mainly hunted in the Delta and Fayum, which is shown by the findings of a large number of bones. The Egyptians apparently knew that Nile cichlids are mouthbrooders, as they regarded the Nile cichlid as a symbol of fertility and rebirth. The brood care of Zille's cichlid was also noticed by the Egyptians and captured by them. According to this, the fish forms a ball from the spawn, which it places in a pit or attached to a stone. Today, perch are the most important edible fish from the Nile and make up more than 70% of the catch. The ancient Egyptian figures are not known, but it can be assumed that the catch numbers were very high and that perch were also important food fish in ancient Egypt. The Nile perch ( Aha in ancient Egyptian ) played a special role and was caught mainly on the fast-flowing and oxygen-rich Upper Nile. The predatory fish could be up to two meters long and weigh 175 kilograms. In some areas of Egypt, they were ritually worshiped and were victims fish for the gods. In the later period they were often mummified and, for example, buried in coffins in large fish necropolises in Esna .

- Catfish came in many different species and were of great economic importance. The watery, less tasty meat, however, was less popular, which is why it can be assumed that catfish were more likely to be eaten by poorer sections of the population. The whiskered catfish were particularly widespread . They have strong dorsal and pectoral fin spines with venom glands on them. These could lead to injuries that were difficult to heal, which is why the sting was broken off by the fishermen immediately after they were caught. The quiver catfish is rare but also hunted . He played an important role in ancient Egyptian medicine.

- Nile pike were mainly caught in stagnant and slow flowing waters. The species Mormyrus kannume was called Oxyrhynchos and was divinely worshiped in several places. The meat of the Nilhechte is on the one hand of less good quality, on the other hand very fatty.

Other fish were the Bynnibarbe , a carp-like fish that Lepidotos was called, different types of tetras and the like ate eel . A particularly characteristic fish that was often shown like the eel was the Nile puffer fish , also known as the fahaka or Maeotis fish . It was widespread and its tasty meat was highly valued. However, the preparation must have been quite difficult as the gonads and liver of the fish contained extremely potent toxins. In science it is controversial whether these puffer fish were worshiped in Elephantine .

Saltwater fish were rarely pictured. The best known are the depictions of around 30 different fish and other marine animals in the punt hall of the temple of Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari . Here in the framework were the representation of Punt expedition that mapped rays , doctor fish , scorpion fish , swordfish , unicorn fish , women fish , puffer fish , sting catfish , flatfish , trigger fish , soldier fish , rabbit fish , wrasses , bat fish , sailfish , sickle fish and lobster , squid and several freshwater fish be identified.

Other vertebrates

The Egyptians only made a limited distinction between different animal species. Crocodiles were worshiped, thousands of which have been handed down in mummified form. The crocodile god Sobek was regarded as the master of the fish, the crocodile as a large fish. The crocodiles, which occur en masse in the Nile, in the canals, in the swamps and in the lakes, enjoyed a high reputation because of their strength and their dangerousness. In some places crocodiles - which also represented a danger to people - were hunted despite their cultic veneration (mostly with harpoons ), as the traditional images suggest. From early settlements near el-Omari it is known that crocodiles were also eaten. Plutarch reports that crocodile meat was also consumed in Edfu . Otherwise no evidence has yet been found that the crocodile was used as food in Pharaonic times. However, in medicine, crocodile eyes have been used to cure eye diseases.

At times turtles were eaten . The most economically important was the Nile soft turtle . It was numerous in the Nile and reached a considerable size; For example, the back armor had a diameter of up to 120 centimeters. The back armor may have been used as shields in prehistoric times, but this has not yet been proven. In the Middle Kingdom , the consumption of turtles ended. They were seen as opponents of the sun god Ra , whom they threatened as animals of the mysterious depths during his nightly dangerous journeys through the underworld in his barge . However, some parts of the turtle were still used in medicine. In many places there are murals, for example in the temples of Philae , Edfu or in Dendera , on which pharaohs are shown ritually hunting and killing turtles.

Mollusks

In addition to the animal species mentioned, mollusks were important for the supply. Remnants of shellfish were already excavated in Stone Age sites, for example in Maadi or Merimde-Benisalâme . The most common was the spathe mussel (also known as the Nile river mussel ) with shells up to 15 centimeters long. She served as a meat supplier. Due to their sharp edges, the bowls were used as tools or, because of their shape, as spoons and as offerings. They also served as a container, for example for make-up. The mussels were an important export item; their shells have also been found in other parts of the Mediterranean, for example in Palestine , Cyprus , the Aegean and Tunisia . The history of the find extends from around 10,000 BC. BC to Byzantine times . It is possible that the exported mussels were salted before they were exported in order to preserve them for a longer period of time. Other types of mussels, such as the mutela , were also consumed in Egypt and exported to Palestine. Also Nilaustern were caught in large quantities and eaten, but probably mainly because of their beautiful, with nacre -lined shells that were made into jewelry. In Pharaonic times, this type of mussel grew on large mussel banks in sections with high currents in Upper Egypt. Today it is almost extinct. Various types of mussels were particularly popular as jewelry. Due to their small size, they were not very suitable as food.

In addition to these freshwater mollusks many molluscs were caught in marine waters. These mussels and snails came mainly from the coasts of the Red Sea . Giant clams were the largest caught; their remains have been found in Maadi and Karnak. In addition, trochidae , cowries , Wulstschnecken different cone snail species and clams consumed in large quantities. Mollusks from the Mediterranean were mainly collected on beaches and cliffs. The most important collectibles were cockles , velvet mussels and fire horn snails , which were hardly traded further than the Nile Delta and the Fayum. It is unclear to what extent these mollusks served as a source of food or were only collected for decorative purposes. Often one found mussel shells and snail shells from maritime areas, which had already been abraded by the surf or even perforated by auger and thus apparently only collected after their death. In addition, such objects were mainly found in the form of pendants, chains and other pieces of jewelry as grave goods, offerings and in profane contexts.

According to current knowledge, squids were not caught. The depiction of squids in the aforementioned punt room is well known. However, during excavations in several places, their inner shell was found , which may have been used for fine grinding work.

Catch

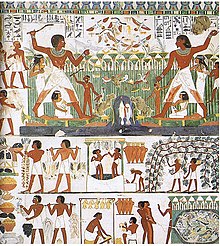

Above all, frescoes or bas-reliefs provide information about the various fishing methods . Fishing hooks, harpoons as well as nets and net accessories were found. It is noticeable that the ancient Egyptians were already familiar with almost all of the fishing techniques used today.

The simplest and oldest fishing method was to collect water animals on the bank and in shallow water. The floodplains of the Nile were very suitable for this. Especially during the decline of the annual Nile flood, people could catch fish and other animals in lagging and slowly drying ponds. This practice is also known from grave inscriptions . In addition, small dams ( fish fences ) were built to hold back the fish. The fish were prevented from escaping with telescopic baskets. These braided containers, closed at the top, were also a means of transport. There is some evidence that fishing was followed by diving in deeper water. The crocodiles in particular made this fishing method very unsafe.

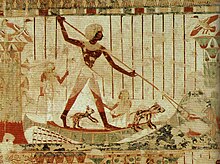

A traditional fishing method was the use of spears and harpoons. This method was often depicted in graves. Usually, the grave lord is shown, who is pounded through the water in a boat and spears for fish. The representation is often supplemented by a picture of the grave master hunting birds with the help of throwing sticks . Usually two fish are pierced by the hunter, usually a Nile perch and a Nile cichlid. Other fish species are rare. Since the habitats of both fish species differ, such a simultaneous catch is unrealistic. The Nile perch was mainly caught in the deep, fast water of Upper Egypt, whereas the Nile cichlid was caught in the shallow, plant-rich and calm delta.

This suggests that the representation is of a symbolic nature and should symbolize the unity of Upper and Lower Egypt. In the late stages of Egyptian history, two Nile cichlids are often depicted and the meaning of the depiction seems to have changed. Now the two fish symbolize fertility and rebirth. Nevertheless, the representations showed real events. Spearheads and harpoons were often found during excavations. In addition, it seems that this type of fishing was primarily a leisure activity of the upper class. Both on grave inscriptions and in papyri , the amusements of this type of hunting were described by various dignitaries.

Also quite often fishermen were pictured fishing , which suggests that this type of fishing was also widespread. Like spear and harpooning, fishing was an elite pastime. Fishhooks have been known in Egypt since the Stone Age. At first they were mainly made from bone, horn, conch shells and ivory, and since the Copper Age also from copper. But it was only in the course of the Old Kingdom that hooks made of copper or bronze replaced all other materials. By the 12th Dynasty (around 1900 BC), the hooks had a simple curved or angled shape without barbs. The introduction of the barbs presumably improved the catch results considerably, and since the 18th dynasty they almost completely replaced the simple hooks. In the late period (around 600 BC) the hooks were increasingly made of iron. In addition to curved hooks, fish gags were also used. These were inverted T-shaped hooks with two points. These flint or bone hooks were attached to a fishing line in the center. They were only found in the Fayum and so far have never been identified in pictures. Hand rods were mostly used with several hooks on a line, sometimes solids such as stones were used as sinkers. The anglers sat on a kind of chair in their papyrus boat and held the line in their hands. The anglers depicted are often older men, so it is possible that this type of fishing was practiced by men who were no longer strong enough for more strenuous fishing methods. So far, bait has never been found in portraits, so it is unclear whether they were used or whether the hooks were only pulled through groups of fish in the hope of spearing fish. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead alone there is a reference to bait at one point. The first depiction of a fishing rod comes from the grave of Khnumhotep in Beni Hasan (around 1950 BC). Several lines were usually attached to rods. Basically, many species of fish could be caught in this way, mostly the catch of whiskered catfish, predatory catfish, puffer fish and barbel was shown.

Again from murals, the catch with the help of fish traps is known. They were probably made of thatch . Internal restraint mechanisms are not visible, but they must have been present. It is not known, but it is very likely, that bait was used to attract the animals. Fish traps were either laid out individually or in groups - usually in opposite rows - and attached to stakes or with the help of ropes on the bank. It is noticeable that after the Old Kingdom, fishing with fish traps was rarely shown. However, it cannot be assumed that this type of catch was no longer as common.

In addition to the use of spears, fishing with nets is the most common motif shown in pictures. The simplest nets were hand nets and landing nets . The amount of fish depicted is probably an artistic exaggeration, which was mainly used to depict many different species of fish. Fishing with large traction nets (“seine fishing”) was far more complex, but probably particularly profitable. This type of fishing has been found in at least 78 graves of the Old Kingdom, which is why this fishing method can be reconstructed quite well. Floats and weights held the nets of different lengths, which were bordered at the top and bottom with strips of linen, in a vertical position. The floats were made of reed or wood, the countersinks were made of stone, possibly also of clay and, later, of lead. Unlike the swimmers made of plant-based materials, the sinkers can still be seen today through archaeological finds. Some pieces of nets have even survived. The meshwork was made from papyrus, flax or other plant fibers. The nets were fixed together with weaver knots . The mesh size was very small with a maximum of 1.9 cm. Thus the nets must have created considerable resistance when pulled through the water. So many fishermen were needed for this type of fishing. 28 men and a foreman are shown on a grave picture. There appears to have been trawling as well. In the tomb of Mektirê, models of two papyrus boats were found with a mesh bag between them. Casting nets have apparently only been used since Roman times, which is particularly surprising because this type of fishing in Mesopotamia has been known for a long time.

Processing, trading and use

In contrast to meat, a luxury good, fish was eaten every day, especially by the lower classes of the population, because it was a cheap folk food. Fish were also processed and consumed in large quantities in the palaces and temples. It can be assumed that a large part of the more expensive fish species was consumed here. There are even fish ponds known from murals, in which mainly Nile cichlids were kept. It is unclear whether they were also bred or even kept as ornamental fish.

The oldest traces that can be counted for the consumption of fish come from predynastic times and are dated between 4000 and 3500 years BC. Dated. In the stomach of a female stool in Naga-ed-Deir near Girga in Upper Egypt, the remains of a fish meal were found. The fish identified as cichlid was obviously eaten with its head and scales. Remnants of white fish were found in the stomach of another mummy .

Fish were generally fried or boiled, less often dried or brine. The types and steps of processing are well known from murals. If the fish were not processed on board the papyrus boats, they were brought ashore and further processed there. Large fish were hung on oar poles and transported in this way. To do this, you cut the fish from the back. If the fish were not processed whole, they were divided with knives on oblique wooden blocks. Different species of fish were cut up in different ways. Dried fish were left untreated or salted in the hot sand. The ovaries were removed from mullets and collected. The roe was then eaten fresh, dried or processed into the already mentioned expensive caviar-like delicacy called batarak . To do this, the ovaries were placed in brine, then shaped into balls, pressed between two boards and placed in the sun to dry. This processing method was used until the end of the 19th century. The center of this production was the city of Phagroriopolis .

To make fish more durable, they were mainly with salt preserved , there was in Egypt in many places. In temples, staff were assigned specifically for this work. The Egyptian word for this work was the same as for mummification. The smoking of fish was unknown, not least because of the high cost of wood. In addition, the warm climate in Egypt made drying out an easier way of preservation. The fish was transported on the Nile with transport sailors, which was particularly worthwhile with coveted mullets. In the late period, salt fish were produced in larger companies in the Nile Delta , which was also a popular item outside of Egypt.

Up until the Ptolemaic times, trade was an exchange-based trade. Apparently there was a fixed system in place. A fisherman could therefore know in advance what he would get in return for his catch. In addition to independent fishermen, there were also those who worked for state institutions and therefore had to deliver their catch. A mural shows a clerk waiting for the fishermen returning home. Ramses IV employed in the middle of the 12th century BC. Around 200 fishermen to feed his court and harem. Both fishermen and landlords who employed fishermen had to pay taxes in kind. In the late period of the empire, 10 percent was common. The workers who worked on major projects on behalf of temples or the pharaohs were also supplied with fish. In the Harris I papyrus , Ramses IV praises his father Ramses III. as the donor of 441,000 whole fish and another 15,500 dried and 2,000 fresh fish to the temple of Amun-Re in Thebes.

In addition to the processing methods described, fish was also used medicinally. In the Ebers Papyrus nine applications are described. The Kahun Papyrus even explains veterinary treatment options for fish.

Fish cult

The Gardiner List , a modern collection of Egyptian hieroglyphics . It shows seven different characters that represent fish or parts of fish.

Many connections of the ancient Egyptian religion have not yet been researched, this applies not least to the religious interactions between humans and fish and to the importance of fish for the cult of the dead. Animals and animal cults, such as the falcon-headed Horus or the jackal-like Anubis, were part of the common repertoire of Egyptian religion. Fish already played an essential role in older cults. In the teaching for King Merikare from around 2060 BC The creation of fish for humans by a god is described. In various districts certain fish species were partially off-limits and could not be eaten. Especially in the delta and in the Fayum, where there were a particularly large number of fish, some of them were worshiped divinely. Basically every city had its own animals that were sacred and taboo. In the northern delta, in the 16th district with the large city of Mendes , the Mendes fish has been venerated since the fourth dynasty (2600–2475). He was the symbol of the fish goddess Hatmehit . One of their names was "First of the Fish". Figurative representations of the goddess show her with a fish, the glass catfish, on her head.

The tilapia cichlid enjoyed particular reverence in large parts of the country . He was mainly worshiped in the tenth district of Upper Egypt and in the city of Dendera . The importance of the fish as a symbol of fertility has already been mentioned several times. It has also been referred to as Chromis (red fish) , which alludes to its reddish color and its relationship to the sun god Re and his daughter Hathor . Murals, inscriptions and texts from the books of the dead show the tilapia alongside some other unidentifiable fish as companions of the solar barge of Ra. He kept the ship from getting stranded and warned the god of dangers. The fish was often carried in amulet form as a lucky charm. In the New Kingdom, decorative objects in the form of fish were given as grave goods. The Oxyrhynchos ( nasal pike , also known as pointed nose ) was also highly respected, especially in the 19th Upper Egyptian district with the city called Oxyrhynchos by the Greeks . Also known is the fish cemetery near the place where many mummies of this sacred fish were buried. The fish was also worshiped in Abydos and Esna . Often bronze portraits of the fish were created, sometimes the fish even got cow horns and the sun disk was placed on the back. The disk was the symbol of the love goddess Hathor, the city goddess of Esna. In the 19th district, fishermen were not allowed to catch Nile pike and therefore did not use fish hooks. There is even said to have been a war between the cities of Oxyrhynchos and Kynopolis . In Oxyrhynchos, a dog, sacred to the Cynopoly, was killed in response to the eating of Nile pike in Kynopolis.

In Lepidopolis near Abydos the Lepidotos fish ( Bynnibarbe ) was worshiped. Various bronze figures have been found from the late period, in Thebes mummies of the fish. They were buried in wooden, barbel-shaped sarcophagi. These fish were a symbol of the city goddess of Abydos, Mehit . Especially the people of Aswan was Phagros sacred. He was considered the messenger of the Nile god Hapi and announced the annual flood of the Nile as his messenger. The fish was also worshiped in Heliopolis and Phagroriopolis. It is not entirely certain which fish can be identified as phagros, it was probably the mullets. In addition to the Nile pike, the Nile perch, which was called Latos , was also venerated in Esna . The Greeks therefore gave the city the name Latopolis . The fish was considered a manifestation of the creator goddess Neith . She was the city goddess of Sais , where a bronze coffin with mummified Nile perches, probably intended as an offering, was found. There was also a fish necropolis near Esna, where mummified Nile perches were buried in Ptolemaic times.

Another fish cemetery was found in Medinet Gorub in Fayum. Nile perches were buried here again. However, there were also whiskered catfish, predatory catfish and spiny catfish. In Bubastis one found the representation of catfish-headed demons from the time of the Old Kingdom. Puffer fish were worshiped as sacred animals in several places, such as Aswan, Elephantine and Nebyt / Kom Ombo . Similar to the mullets, it showed the approaching Nile flood. In the eastern Nile Delta, the eel was regarded as sacred and was considered the sacred animal of the primordial god Atum . Several specimens were found in Sais and were buried in small bronze coffins.

The reports on the status of the individual fish are quite ambivalent in the tradition . Although fish were considered sacred in some regions, some species were also despised because they were considered unclean or evil. Only according to Plutarch , De Iside et Osiride , but not according to Egyptian sources, there were three wicked fish, the Oxyrhynchos fish, the Lepidotos and the Phagros, who had molested the corpse of the god of the dead Osiris by swallowing his phallus . Fish were not only eaten by humans, but also fed to sacred animals. In tomb paintings, the deceased were often depicted eating fish. In coffin texts of the Middle Kingdom, fish are given as food in the realm of the dead. Fish have also been found as offerings in graves. The oldest depiction of a fish as a gift in a religious context is a small plaque, which is attributed to King Djer (around 2900 BC). The depiction of fish victims is, however, quite rare overall.

The frequently depicted fish scenes in burial chambers also had religious backgrounds beyond the already mentioned cultic significance. If the grave lords were shown hunting and fishing, this symbolized victory over chaos. The fish shown were not simply decoration, but were intended to provide for the deceased in the afterlife. A wall painting in the tomb of Chabrechnet in Deir el-Medina even shows the transformation of the deceased into a fish . The depicted fish replaces the usual depiction of a mummy. Representations have been found several times in which the Ba-bird representing the ability of the soul to move was replaced by a fish. One fear of the Egyptians was to get caught in the nets after death and thus not survive in the afterlife. The deceased also had to be protected from other dangers such as the "fishcutter". One tried to accomplish this with the help of incantations. But even in this world one tried to exert magical influence. So priests should use their magic to protect fishermen from crocodiles. In addition, there were festivals in some places, such as the festival of Behedet in Edfu , where fish were ritually trampled underfoot by priests. In Esna, fish were regularly burned on the first day of Payni . In many places, priests were not allowed to eat fish before ceremonies. In the New Kingdom there were even calendar lists with such food bans. It can therefore be assumed that Pisces made priests unclean for certain actions. The Pharaoh Pije , who came from Nubia, apparently even had a personal aversion to fish, as he banished them from his royal court and did not want to associate with Egyptian princes who were uncircumcised and fish-eaters.

literature

- Joachim Boessneck: The animal world of ancient Egypt. Investigated on the basis of cultural-historical and zoological sources . CH Beck, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-406-33365-6 .

- Angela von den Driesch : Fish in Ancient Egypt. An osteoarchaeological study (= Documenta naturae. No. 34, ISSN 0723-8428 ). Chancellor, Munich 1986.

- Heinz Felber: fishing, fishing industry. II. Egypt. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 4, Metzler, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-476-01474-6 , Sp. 527.

- Ingrid Gamer-Wallert : Fish and fish cults in ancient Egypt (= Egyptological treatises. Vol. 21). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1970, ISBN 3-447-00779-6 .

- Dietrich Sahrhage : Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 70). von Zabern, Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-8053-1757-3 .

Remarks

- ^ A b Heinz Felber: fishing, fishing industry. II. Egypt , in: Der Neue Pauly Volume 4 (1998), Col. 527

- ↑ ( Num 11,5 LUT ) “We think of the fish that we got to eat for free in Egypt” .

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 77

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 57

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 80

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 58

- ↑ So on the seasonal reliefs of the so-called “World Chamber” in the sun sanctuary of Niuserre , which can be seen today in Berlin , or in the Unas pyramid in Saqqara

- ↑ Ingrid Gamer-Wallert: Fish and Fish Cults in Ancient Egypt, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1970, pp. 47–50

- ^ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 62–66

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 66–69

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 69f.

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 71

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 77–82

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 74f.

- ↑ Joachim Boessneck: The animal world of ancient Egypt. Investigated on the basis of cultural-historical and zoological sources, CH Beck, Munich 1988, p. 25

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 76f.

- ↑ Joachim Boessneck: The animal world of ancient Egypt. Investigated on the basis of cultural-historical and zoological sources, CH Beck, Munich 1988, pp. 145–47

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 82–84

- ^ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 84–86

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 86

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 87-88

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 88–94

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 94-100

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 101-103

- ↑ Today, remains of the net can be found in the Egyptian collections in Cairo, Berlin, in the Louvre in Paris, and elsewhere

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 104–112

- ↑ a b Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 123

- ^ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 123–128

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 128–129

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, p. 132

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 129–132

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 132-133

- ↑ Ingrid Gamer-Wallert: Fish and Fish Cults in Ancient Egypt, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1970, pp. 86–119

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 136-137

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 137–141

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 142–144

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 144–146

- ↑ Ingrid Gamer-Wallert, in: Lexikon der Ägyptologie , Volume IV, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1982, Sp. 1017f

- ↑ Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 146–148

- ↑ Grave number TT 2

- ↑ This is how it is described on the victory stele of Pije. Dietrich Sahrhage: Fishing and fish cult in ancient Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 148–153