Ernst Gennat

Ernst August Ferdinand Gennat (born January 1, 1880 in Plötzensee , † August 21, 1939 in Berlin ) was an officer in the Berlin criminal police . For more than 30 years he worked under three political systems as one of the most talented and successful criminalists in Germany. Already in his lifetime legend and original alike, it did not correspond to the classic cliché of the narrow-minded Prussian official.

Behind his back he was kindly or maliciously called " Buddha of the Criminologists" or "Seriously" by his colleagues . On the other side he was often referred to as "The Fat One from Alexanderplatz" because his office was located there. These nicknames alluded to his imposing body.

The young Gennat

Through his father, the chief inspector of the "New Prison" Plötzensee (also known as the "Plötze" in the vernacular), the young Gennat came into contact with the social and economic plight of the lowest strata of the population at an early age. According to the address book entry from 1880, the Gennat family (mother Clara Luise, née Bergemann, father August and son Ernst August Ferdinand) lived in a staff apartment in the "New Prison".

After primary school, Gennat attended the Königliche Luisen-Gymnasium at Turmstrasse 87 in Berlin and passed the Abitur examination on September 13, 1898 . It is unclear what he did for the next three years up to his matriculation on October 18, 1901. Gennat probably completed his military service in the army during this time , because in the university register under number 37 - heading "Future occupation" - Gennat noted succinctly: "Military".

He then studied law for eight semesters at Berlin's Friedrich Wilhelms University . On July 12, 1905, he was deleted from the matriculation - before the end of the semester on August 15. From the official side it was noted: “wg. Unfl. ”(“ Because of carelessness ”). This formula did not mean that Gennat was "hardworking", but that he left university without a diploma. The reason for this was his decision to join the criminal investigation department .

Gennat and the Berlin "Adelsclub"

In 1904 Gennat entered the Prussian police service. On May 30, 1905, the detective passed the detective examination, two days later he was appointed assistant detective and on August 1, detective.

The leadership and the most important departments of the Berlin police resided in the huge red brick building of the police headquarters on Alexanderplatz in Berlin-Mitte (built 1886–1889, partly destroyed in World War II and demolished in 1960). Before the First World War , most civil servants in the higher and higher criminal service (from the detective inspector upwards) were recruited on the one hand from officers who had quit military service for financial reasons, and on the other from descendants of impoverished aristocratic families who, due to their unfortunate economic situation, also had a career aspired in civil service. A high school diploma was a condition for commissioner candidates. Most of the candidates had studied (with or without a degree), mostly law or medicine . Not all of them came to the criminal investigation department out of passion. After the war and the inflation , the number of academics rose who were forced to drop out of their studies and earn money or who had completed their studies, even with doctoral degrees, were happy to find employment in the civil service. In 1932 there were no fewer than 22 doctorates among the 132 detective inspectors .

Gennats “Mordinspektion” at the Berlin police headquarters

During the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) the criminal police formed the core of Department IV of the Berlin Police Headquarters . It was divided into local and specialist inspections .

The 14 local inspections played only a minor role; sometimes officials who had fallen out of favor in the praesidium were "banished" there. It was only towards the end of the Weimar Republic that plans matured to give the local inspections more independence.

In total, there were nine specialist inspections:

Department IV (Criminal Police) inspections:

- Inspection A: Murder and Assault

- Inspection B: Robbery

- Inspection C: Theft

- Inspection D: Fraud, Fraud, and Counterfeiting

- Inspection E: Morals Police

- Inspection F: Trade and Bankruptcy Code Violations

- Inspection G: Female Criminal Police , WKP (mainly female officers from 1927)

- Inspection H: wanted police

- Inspection I: Detection Service , ED

When Gennat joined the criminal investigation department in 1904, there was no homicide commission in the true sense of the word. It was not until August 25, 1902, that a so-called “murder standby service” was set up within the criminal police so that officers could be sent to the crime scene immediately at any time of the day or night. Until then, the management of the criminal police had only started to find suitable investigators when needed, so it sometimes took hours before the officers arrived at the scene.

The establishment of the State Criminal Police Office (LKPA) for Prussia , which began its work on June 1, 1925, did not change the fact that there was a clear deficit in the investigation of crimes in Prussia at that time .

It was only through Gennat's efforts that the murder stand-by service became an organizationally firmly established “Central Murder Inspection” in Inspection A, which officially began its work on January 1, 1926 and was in charge of it. It was only on this occasion that he was promoted to the criminal police officer in 1925, at the age of 45. His basic democratic attitude, unusually for a Prussian civil servant, and his willingness to criticize grievances bluntly, had had an adverse effect on his career despite his undeniable successes. Deputy head of Gennat's Inspection A was Dr. Ludwig Werneburg , who headed inspection B during the twenties.

As a result, the Central Murder Inspection received worldwide attention, recognition and imitation. As head of his new inspection, Gennat not only coordinated the homicide commissions, but was in control of all murder investigations and selected even the most capable criminologists.

The murder inspection consisted of an "active" and two "reserve murder commissions". The active homicide commission included an older and a younger commissioner (who then led a so-called “murder marriage”), four to ten detectives, a stenographer and, if necessary (at the crime scene), a dog handler and the identification service. She dealt with all murder and manslaughter matters in Berlin. The two reserve commissions were each assigned a commissioner and two or three detectives plus a typist. The employees were made up of officials from various inspections, who rotated every four weeks, as everyone should gather this valuable professional experience once.

In 1931 the Central Murder Inspectorate was able to find 108 homicides out of 114, i. H. Clarify 94.7% (for comparison: the clarification rate for murders is now between 85 and 95%). By comparison, the robbery department only achieved a rate of 52 percent in 1931. Gennat himself succeeded in solving 298 murders during his 33 years in the police force.

In addition to the advances in organization and investigation techniques, it was not least Gennat's personal characteristics that made him so successful. His tenacity and perseverance, his phenomenal memory and enormous psychological empathy, which enabled him to practice “ profiling ” forty years before the term was invented, were particularly praised . He refused to use force during interrogations and (police) interviews. He urged his co-workers: “Anyone who touches a suspect will fly! Our weapons are brains and nerves! ”In addition, Gennat (and not Robert Ressler ) coined the term“ serial killer ” in his 1930 essay“ Die Düsseldorfer Sexualverbrechen ”(about Peter Kürten ) . In many respects Gennat appears surprisingly modern: He emphasized the importance of prevention over the investigation of crimes and was aware of the effect of capital crimes on the public and the opinion-forming role of the press, which he sought to make fruitful for investigative work.

In addition to his dry Berlin humor and the many anecdotes and bonmots that have been told about him, Gennat's striking body (he weighed an estimated 135 kg) made the “fat man from the homicide squad” a well-known original. He owed it to his enormous appetite, especially his passion for (gooseberry) cakes. It was not without reason that his secretary Gertrud Steiner was nicknamed "Bockwurst-Trudchen".

Another curiosity was Gennat's office on the first floor of the Berlin police headquarters, opposite the tram route on Dircksenstrasse. “[It was] an incomparable mixture of plush, cozy living room and horror cabinet [...]. No other homicide squad's office is likely to be so original. ”(Regina Stürickow). The focus in Gennat's office was a sagging green sofa and two sagging green plush armchairs. A meter above hung a console on which stood a prepared woman's head, which had once been recovered from the Spree, wrapped in paper and used by the detectives as a cigarette dispenser. In the corner next to the sofa leaned against an ax that was once a tool in a homicide. Photographs of male and female murderers and victims as well as a Pharus map of Greater Berlin, yellowed by cigar smoke, completed the decoration.

Advances in Investigation Technique

Building on the scientific criminalistics founded by Hans Gross , Ernst Gennat was one of the first to recognize the importance of accurate evidence securing at the crime scene. Before his time, it was by no means unusual for the first policemen to arrive at the scene of the crime to first “put things in order” or to bed down the corpse piously. Gennat laid down precise guidelines for the procedure at the crime scene and enforced as an unbreakable principle that nothing could be touched or changed before the investigators arrived.

In order to enable thorough and quick investigative work, Gennat had Daimler-Benz AG build a vehicle on call for murder, colloquially known as the "murder car", a passenger car equipped with office and forensic technology (based on the Benz sedan 16/50 hp ). The audience was allowed to view the murder car on the occasion of the “ Great Police Exhibition 1926 ” (September 25th – October 17th, 1926) in Berlin.

If necessary, the murder car could be converted into a makeshift office. A typewriter (with a typist) was part of the inventory as well as a folding table and folding chairs so that people could work outdoors, as well as two retractable tables mounted inside the car. Immediate work at the crime scene was made up of materials for securing evidence , marking posts made of steel with a triangular field and consecutive numbers. Everything has been thought of: headlights, flashlights, photo material, various tools such as scissors, diamond cutters, axes and large spades, pedometers, calipers and yardstick, rubber gloves, rubber aprons, tweezers , probes and pipettes to collect spilled liquids, as well as suitable lid glasses, cardboard boxes or bottles for storing evidence. Gennat always sat on the right behind the passenger. There he had a special strut installed. His body weight of more than 100 kg would otherwise have put the car in a lopsided position.

The murder commission of the Munich criminal police, newly established in 1927 , was also equipped with a "murder vehicle" and the appropriate equipment.

The “Central File for Murder Matters” or “Death Investigation File” created by Gennat, which was looked after by the detective Otto Knauf for decades, also achieved world fame. It systematically documented all violent deaths that came to light, not only from Berlin. No other police authority had such an extensive collection of case reports as the Central Murder Inspection until 1945. In a very short time, it was possible to reconstruct cases that were long ago in order to reveal possible connections in the actual execution. In addition to original files, press reports and wanted posters served as source material. Ernst Gennat also had investigative files from other police stations sent to him with the request for “inspection” - and occasionally he “forgot” to return them. The systematically structured card index not only included capital crimes , but also contained the headings "Indirect or cold murder" ( suicides due to defamation or false accusations), "Existence destruction through fraudulent deception" (suicides caused by fraudsters, impostors, obscure clairvoyants or marriage swindlers were) and "Existence destruction through blackmail". Gennat was of the opinion that inducement to commit suicide should also be criminalized. Some pieces from the Gennat archive were transferred to the holdings of the Berlin Police History Collection .

In the time of National Socialism

Gennat remained at his post even after the National Socialist seizure of power . The new Prussian Minister of the Interior, Hermann Göring, immediately instructed Gennat's homicide commission to reopen the investigation into the homicides committed by members of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) against Berlin police officers that had not been resolved by the political police in 1931 . In the Paul Zänkert case , which occurred on May 29, 1931 on Senefelderplatz, Gennat was able to convict a suspect who had already been arrested in December 1932 as one of the perpetrators. For the murders on Bülowplatz on August 9, 1931, he investigated the perpetrators Erich Mielke and Erich Ziemer and their escape routes to the Soviet Union . After Gennat's appearance in the Bülowstrasse trial in June 1934, where he testified about his investigations, Göring promoted him to criminal director.

From November 6, 1933, the murder inspection "M I", the special inspection for processing moral crimes "M II" and the female criminal police (WKP) "M III" were combined to form "criminal group M". Gennat took over the management of Kriminalgruppe M, who despite his aloof attitude towards the National Socialists was promoted to the government and criminal councilor in 1935, which entrusted him with the "permanent deputy of the head of the Berlin criminal police".

As a result of this organizational change, the murder inspection received additional tasks. In addition to fire crimes , fatal traffic accidents will also be dealt with in specially created police stations . In 1936, the murder inspection consisted of a total of nine commissariats. From 1936 the Berlin criminal police was separated from the Greater Berlin police apparatus and subordinated to the German Reich , whereby the criminal group M was still on duty in the service building at Alexanderplatz and nothing changed in the actual areas of responsibility.

Gennat only carried out investigations from his office (hence the name “desk detective”), as he found it difficult to walk due to his overweight. He looked after the offspring of the police, planned investigations precisely, interrogated the accused and witnesses, still found errors in investigations with a sleepwalking certainty, gave lectures and wrote essays such as the well-known series of articles "The processing of murder (death investigation) matters". It is noticeable that in all of his articles written after 1933 he never used terms or phrases of the new rulers, he only used the word “takeover” once. Under his influence there were only a few officials who sympathized with the National Socialists. As a liberal democrat , Gennat was for his colleagues the personification of the classic criminalist: undogmatic, incorruptible and always ready to protect the personal rights of the individual.

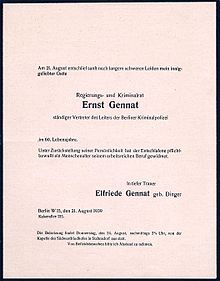

"The ingenious criminalist Gennat [...] this good-natured, philanthropic, always sloppily dressed gentleman [...], whom almost everyone characterized as a die-hard bachelor " ( Dietrich Nummert ), married a WKP detective in 1939 , Elfriede Things. Since this happened shortly before his death on August 21, 1939 (he suffered from colon cancer , but probably died of a stroke ), some people assumed that he had only taken this step in order to secure the young woman's considerable widow's pension . However, this intention has not been proven. It is believed that he married her so that she could quit the police force because she no longer wanted to work in the National Socialist police apparatus.

Bernd Wehner , a former colleague of Gennat and later Spiegel author, reported on the funeral: “Behind the coffin stepped, as if to mock the humane man, the now grown-up detectives from Werderscher Markt and the Berlin control center, his former students, mostly in SS -Uniform . Far back in the row came his homicide detectors with their head of inspection Werneburg . All in the cylinder. None of them had yet been found worthy to wear the uniform. The officials clearly followed. "

2,000 Berlin detectives followed Gennat's coffin.

Media presence and aftermath in film and literature

Although Gennat had solved a myriad of crimes - not just homicides - as early as the imperial era, he only reached the peak of his popularity in the (early) years of the Weimar Republic and became a kind of media star. The famous murder expert became a piece of Berlin. The daily newspapers reported particularly extensively on murder cases in which Gennat was investigating. If he showed himself at an event of the Berlin high society, his name was mentioned in the social columns of the tabloid press in the same breath as the "celebrities". The Berlin criminal police also often had prominent visitors who were particularly interested in the murder inspection. At the beginning of the 1930s, Heinrich Mann , Charles Chaplin and Edgar Wallace were among its visitors.

On November 7th, 1938 at 8 p.m. Gennat wrote not only criminal history, but also television history: After the murder of a taxi driver, the first TV manhunt with Detective Inspector Theo Saevecke was broadcast on the Paul Nipkow television station. Although there were only 28 public television rooms in Berlin at the time , the numerous in-depth reports led to the perpetrator being arrested.

Gennat was the godfather of the “ancestor” of the German television commissioners, “Kriminalkommissar Karl Lohmann”: heavyweight, jovial, patriarchal-authoritarian. He made his first appearances in the Fritz Lang films M (1931) and Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (1933). Both times he was played by Otto Wernicke . In a successful series of books, the writer Hans G. Bentz designed the criminal inspector Türk based on Gennat's example. The TV film “ Mordkommission Berlin 1 ” from 2015, with its main character Paul Lang, is loosely based on Ernst Gennat. In the feature film Fritz Lang - The Other in Us by Gordian Maugg (2016), Gennat is played by Thomas Thieme . Ernst Gennat and Inspector A, which he heads, also play a major role in the historical crime novels by Volker Kutscher about the fictional detective Gereon Rath, who initially works for the moral police before switching to the murder inspection. In the crime series Babylon Berlin based on the novels , Gennat is portrayed by Udo Samel .

Works

- Ernst Gennat: The Düsseldorf Sex Murders. In: Kriminalistische Monatshefte 1930, ZDB -ID 206467-4 , pp. 2–7, 27–32, 49–54, 79–82.

- Ernst Gennat: The Kürten Trial. In: Kriminalistische Monatshefte 1931, ZDB -ID 206467-4 , pp. 108–111, 130–133.

literature

Specialist literature

- Karl Berg : The sadist. The case of Peter Kürten. Belleville, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-923646-12-7 (forensic medicine and criminal psychology on the deeds of the Düsseldorf murderer Peter Kürten , first published in 1931).

- Sace Elder: Murder Scenes. Normality, Deviance, and Criminal Violence in Weimar Berlin . The University of Michigan Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-472-11724-6 .

- Hsi-Huey Liang: The Berlin Police in the Weimar Republic . De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1977, ISBN 978-3-11-006520-6 .

- Dietrich Nummert : Buddha or seriousness. The criminalist Ernst Gennat (1880–1939). In: Berlinische Monatsschrift, issue 10/2000, pp. 64–70.

Non-fiction

- Franz von Schmidt: Demonstrated appears. Experienced criminalistics. Stuttgart house library, Stuttgart 1955.

- Franz von Schmidt: Murder in the Twilight. Experienced criminal history. Verlag Deutsche Volksbücher, Stuttgart 1961.

- Regina Stürickow: The Commissioner from Alexanderplatz. Structure of the Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7466-1383-3 (biography).

- Regina Stürickow: Murderous Metropolis Berlin. Criminal cases 1914–1933. Militzke, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-86189-708-3 .

- Regina Stürickow: Murderous Metropolis Berlin. Criminal cases in the Third Reich. Militzke, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-86189-741-5 .

- Regina Stürickow: Crimes in Berlin. 32 historical criminal cases. 2nd Edition. Elsengold Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-944594-18-7 .

- Regina Stürickow: Commissioner Gennat determined. The invention of the homicide squad. 2nd Edition. Elsengold Verlag, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-944594-56-9 .

Novels

-

Hans G. Bentz , director of crime in Türk

- Faster than death

- Detective Director Turk's worst case

- The fat man and the mafia

- The strange face

- Philip Kerr : The last experiment. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8052-0869-7 (historical crime novel).

- Martin Keune : Black Bottom be.bra verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-89809-528-0 (historical crime novel).

- Martin Keune: Die Blender be.bra Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-89809-533-4 (historical crime novel).

- Volker Kutscher : The wet fish. Gereon Rath's first case. Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2008, ISBN 3-462-04022-7 (historical crime novel).

- Volker Kutscher: The silent death. Gereon Rath's second case. Publishing house Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2009, ISBN 3-462-04074-X (historical detective novel).

- Volker Kutscher: Goldstein. Gereon Rath's third case . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2010, ISBN 978-3-462-04238-2 .

- Volker Kutscher: The Fatherland Files. Gereon Rath's fourth case . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-462-04466-9 .

- Volker Kutscher: Those who fell in March. Gereon Rath's fifth case. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-462-04707-3 .

- Volker Kutscher: Lunapark. Gereon Rath's sixth case. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-462-04923-7 .

- Volker Kutscher: Marlow. The seventh Rath novel , Piper, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-492-05594-9 .

- Regina Stürickow: Greed. Berlin-Krimi-Verlag, Berlin-Brandenburg 2003, ISBN 3-89809-025-6 (historical crime novel, based on the authentic murder case Martha Franzke from 1916).

- Susanne Goga : The dead from Charlottenburg. dtv, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-423-21381-3 (historical crime novel).

- Friedrich Karl Kaul: Murder in Grunewald (East) Berlin 1957 (novel on the Rathenau murder)

Television documentary

- Crime scene Berlin: Ernst Gennat - The murder inspector from Alex. Documentary by Gabi Schlag and Benno Wenz. rbb 2011.

- The first cop - How Ernst Gennat invented modern police work. Documentary. Sat.1 2015

Web links

- Police History Collection Berlin ( Memento from November 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Article from "DeutschlandRadio Berlin" ( Memento from September 27, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- Tatort Berlin: Ernst Gennat - The Murder Inspector from Alex ( Memento from October 21, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- Photos of Ernst Gennat and employees at Getty Images

- Report on the "Killer Car" of the Budapest police, which is based on the Berlin murder car, Hungarian

Individual evidence

- ↑ ZDF documentary: Terra X: Treacherous Traces - The History of Forensics. Part 1: What unmasked perpetrators. First broadcast on ZDF on October 14, 2018, 7.30 p.m., video available until October 14, 2028, accessed on June 13, 2020, from minute 5.58.

- ↑ Dietrich Nummert : Buddha or the full seriousness. The criminalist Ernst Gennat . In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 10, 1999, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 64–70 ( luise-berlin.de ).

- ↑ On this in general Wilfriede Otto : Erich Mielke - Biography. The rise and fall of a chekist . Karl Dietz, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-320-01976-7 , p. 37, without mentioning Gennat's murder commission.

- ↑ On the course of the investigation by Gennat see Michael Stricker: Last use. Police officers killed on duty in Berlin from 1918 to 2010 . Verlag für Polizeiwissenschaft, Frankfurt 2010, ISBN 3-86676-141-4 , on Zänkert p. 49–57, on Bülowplatz p. 63–106, here p. 85 ff. The police historical collection (Berlin) shows a facsimile protocol of the interrogation Mielke's mother through Gennat.

- ↑ Thomas Klug and C. Bukowski: From Landjägerei to Science: the first murder commission article, in: NZZ from August 25, 2002; Retrieved on: September 8, 2013

- ^ Frank Kempe: The founder of the first permanent homicide commission. In: Calendar sheet (broadcast on DLF ). August 21, 2014, accessed August 21, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Friendship between Gennat and Bentz on Krimilexikon.de

- ↑ Criticism of Murder Commission Berlin 1 on focus.de

- ^ Tatort Berlin: Ernst Gennat - Der Mordinspektor vom Alex ( Memento from October 21, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) at rbb-online, accessed on October 22, 2013.

- ↑ On the search for traces: Gripping documentation “The first cop - How Ernst Gennat invented modern police work” on Tuesday, December 1, 2015, at 10:55 pm on SAT.1. In: presseportal.de. November 29, 2015, accessed December 1, 2015 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gennat, Ernst |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gennat, Ernst August Ferdinand (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German criminal investigator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 1, 1880 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Plötzensee |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 21, 1939 |

| Place of death | Berlin |