History of automata

The history of the automat begins in antiquity . In addition to numerous myths and legends, the first historically documented real machines can also be found here . The main interest of the machine builder was primarily the research of physics and / or the mapping of nature with technical means. There were also useful automatons, but the utility aspect was not in the foreground (most likely useful automatons were used for water art and military purposes). It was not until the 18th century that Vaucanson (see below) made the transition from the “wonderful” to the “useful”, which from then on exist side by side in machine construction.

Antiquity

Mythological automatons

Already in Greek mythology there are a lot of artificial birds, walking and talking statues and artificial servants. Homer reports in his Iliad that Hephaestus , the god of handicrafts, made self-driving vehicles and even artificial servants who were intelligent and learned handicrafts. There are many accounts from historians of ancient Greece and ancient Rome with detailed descriptions of self-propelled and self-propelled mechanisms and androids. Similar tales are known from other early cultures, especially China. Of course, it is difficult to distinguish between myth and truth.

Ancient Greece - the Alexandrian School

In Alexandria researched and taught high-ranking natural philosophers who are known as the Alexandrian School . They include: B. Heron , Pythagoras and Euclid , but also Archimedes must be included, although he worked in Syracuse, which, however, belonged to the Alexandria cultural area.

The Alexandrian inventors were masters in combining the so-called "simple machines" such as screws, wedges, levers, etc. to carry out complex movements and in the combination of water, vacuum and air pressure as their driving force. Heron of Alexandria explains e.g. B. in his work Automata temple doors that open automatically as if by magic, and in addition to music machines, he also developed automatic theater with amazing effects.

He and others have come up with an inexhaustible number of suggestions for birds that flap their wings and chirp, for whole series of magic vessels with intermittent discharge or automatons from which water and then again wine flow or which after a coin has been inserted a certain amount Give holy water. In the Alexandrian School many "programmed simulators and automata and devices (s) with feedback " were invented which - such as e.g. B. flushing water in toilets - are still used today.

The Arabic interlude

While much ancient literature was lost in Central Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire , it was preserved in many cases in the Arab world. In the early 9th century the Caliph of Baghdad Abdallah-al-Manun even commissioned the three sons of his court astrologer to systematically search for them and buy up everything they could find.

They translated works a. a. by Heron ( see above ) and revised them. The great work Kitab al-Haiyal ("The Book of Artful Devices") became a standard work and can often easily be traced back to the Alexandrian School (see above). The practical application is very important to the authors. One of them was the manufacture of clocks , which now took a great boom.

Most of the works of this culture were irretrievably destroyed when the Mongols attacked Arab domination, with Baghdad falling in 1258.

Middle Ages to 17th century

Late Middle Ages

Towards the end of the Middle Ages , scholars in monasteries in Central Europe began to grapple with the ancient writings and the Arabic versions and further developments thereof.

There is a legend about Albertus Magnus (1193? –1280) that he created a "speaking statue" that his student Thomas Aquinas destroyed. In modern times it has sometimes been interpreted as if it were about achievements in the field of technology. The scholars in the second half of the 13th century based themselves on the theory of the soul according to the Aristotelian writing De anima , according to which the presence of a soul is a prerequisite for self-movement. For this reason, one would have to “breathe a soul” into a statue, so to speak, so that it can move independently. For Thomas Aquinas, only magic came into consideration, and so he called people who “speak still images and let them move” as necromantici , i.e. H. as a supporter of "black art". (In doing so, he was more likely to have an eye on the ancient reports on mythological automatons, because in the Middle Ages magic mainly had other goals.)

In any case, the invention of the purely mechanical clockwork (until then there had been very complex clocks, but they were only driven by water) and very soon the pure time measurement function was combined with moving figures or striking mechanisms (early 14th century). Only the mechanical cock (around 1350) that flapped its wings at lunchtime, spreading its feathers and crowing, remains of the clock of the Strasbourg cathedral . However, in keeping with the tradition of the Alexandrian School (see above), entire scenes with a religious or secular background were depicted, but now no longer driven by water power, but by clockworks.

Renaissance and Baroque

The Renaissance was also an important period in the history of technology that can be described as the “technical revolution in the Renaissance”.

While the Alexandrian School mostly only built models, technical advances during the Renaissance made it possible to construct life-size automata. From Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was a sketch rediscovered a robot in the 1950s. This robot could move its arms, sit up, and turn its head. (The Bremer Complimentarius seems to be a similar automaton, but this only dates from the 17th century.)

The French engineer Salomon de Caus (1576–1626) wrote his extensive work Les raisons des forces mouvantes ... ("On the moving forces. The description of some artificial and amusing devices") in 1615 . He describes many Heron automatons , but also developed them further. He first built the Hortus Palatinus (Palatinate Garden) in Heidelberg and later in the palace of the Duke of Burgundy in Saint-Germain near Paris, a number of scenes with moving figures that were driven by water wheels and controlled by cam rollers. Similar constructions were set up in Hellbrunn Palace in 1613 , the complex initially only consisted of a few grottos with moving figures, the complex was enlarged in 1748–1752 and contained a total of 256 figures. A hydraulic organ covered the noises of the drive mechanism. For centuries it remained the fashion to decorate pleasure gardens with grottos and moving figures. De Caus was the great pioneer in the construction of life-size automata. After that, many farms had their own designers of androids and other machines, "which ... acted right and bad ...".

In addition, the art of making automatic toys as in antiquity (see above) also developed. One of the great founders of this art movement was Juanelo Turriano , an extraordinarily talented engineer in the service of Charles V of the u. a. solved the water supply of Toledo in a completely new way. He tried to cheer up Charles V after the forced abdication with a lot of small mechanical toys. And his fame was so great that he was believed to have invented an android that supposedly could even go shopping for him.

In Germany, too, there were a number of goldsmiths and precision mechanics who were leaders in machine building, especially in Nuremberg and Augsburg . Hans Schlottheim (1545-1625) e.g. B. probably made the famous Charles V ship around 1585 . The ship has wheels and, when triggered, moves forward on a winding path. An organ is playing, trumpeters raise their instruments on the bridge, drums and cymbals are struck, cannons thunder at regular intervals. At the bow, sailors hoist sails while others take a tour of the ship. At the stern, the emperor himself sits on a canopy throne, lowers his scepter and turns his head while dignitaries bow around him.

If one examines the control mechanisms of the automatons of this pioneering time, one finds that highly developed techniques were often used which "have since been reinvented many times independently of one another."

In the 17th century, automata were finally widespread and were of great interest to the philosophers of the nascent Enlightenment - see below

Cartesianism

The Cartesianism was characterized by a great upsurge of scientific and rational study of the reality. The mechanism saw clear parallels between the laws of mechanics and thus also machines and natural bodies.

René Descartes (1596–1650) treats in his basic work Discours de la méthode u. a. the difference between humans and animals. Both are created by God, but only man has an immortal soul. Animals must be viewed as highly complex machines (la bête machine), as automatons. And he thinks it is quite likely that one day humans will succeed in building a machine in the shape of an animal that would behave like an animal. He compares z. B. the heart with a hydraulic pump and also deals with other organs or with tendons and muscles and describes them very similar to the automatic devices that were widespread at this time. Allegedly, Déscartes built a lifelike android in the shape of a girl named Francine. However, this is very unlikely as he was not a technician. Serious biographers ignore this story entirely.

The German ingenious and learned Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), on the other hand, took up the ideas of Déscartes and put them into practice. B. he built a talking head, singing birds and figures that played musical instruments. He also built automatic theaters for gardens in the tradition of Salomon de Caus .

18th century until today

The 18th century - the heyday of the automatons

In the 18th century, there was great public interest in vending machines, also because cases of fraud were repeatedly uncovered.

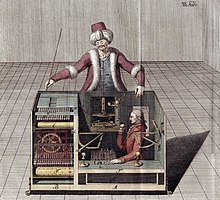

At the end of the 1760s, z. B. Wolfgang von Kempelen presented his "Chess Turks" with whom he toured Europe and the USA and challenged great chess players. There are different views on how the machine was exposed as a hoax. Only a very small person was hidden in the box, there was only one mechanism to move the chess player accordingly.

Von Kempelen also built a speaking machine in which the human speech organs are reproduced as faithfully as possible. The sounds are modulated with the hand of the demonstrator, so it is not an automaton. He was also very successful in other areas of engineering.

There were many reports of self-driving vehicles and other vending machines in the 17th and 18th centuries, most (and some not) of which were exposed as hoaxes. Here a development was sketched out in wishful thinking that did not yet exist at this point in time.

The Vaucanson machines

It was only with the construction of Jacques de Vaucanson (1709–1782) that a high point in the history of the construction of real automatons was reached.

In 1735 he came to Paris from Grenoble to deal with automatons, which were very fashionable at the time. But first he started studying anatomy . He wanted to build, as it were, moving three-dimensional anatomy models (anatomie mouvante - moving anatomy). This would have translated the philosophical principles of René Descartes into technical reality (so "Cartesianism").

After much careful work and a few failures, he built a life-size, flute-playing shepherd. Although it had lips, mouth and tongue, it was not an anatomical model corresponding to reality, but an automaton operated with clockworks and bellows . The flute player nonetheless caused a stir when it was introduced in 1738 and spurred him on to build another automaton, a shepherd who played the flute and accompanied himself on a tambourine at the same time .

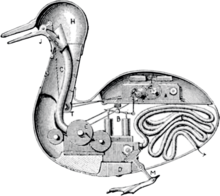

Vaucanson tried to pursue the idea of his “moving anatomy” with a mechanical duck that waddled around, but could also eat, digest and excrete. In doing so, he invented the rubber hose and a machine to manufacture it. In 1743 he sold his apparatus; In 1748 the mechanical creatures can be found in Augsburg:

- “With the gracious permission of a high authority, the 3rd moor, so famous in all of Europe and admired by Mr. Vaucanson, a member of the royal family, are dressed here in the guest = court of the 3rd Moors. French Academy of Sciences, invented and manufactured, to be seen for the first time. This 3rd mechanical art = pieces which seem to surpass human understanding, and whose value can only be seen and explained by great connoisseurs, contain in their internal structure a connection between many arts and sciences, but mainly they are masterpieces of anatomy, Physic, Mechanic and Music. Connoisseurs will find use and pleasure in this, but curious lovers will be amazed. The first figure represents a seated man the size of Holtz's life, who, II. Blows different arias on the flute traverse, with just the comfort and skill as this instrument requires, and with the same air in the mouth = hole, gripping of notes, movement of fingers, lips and tongue, as a living person is used to doing. The 2nd is a man = person from a cardboard cover, who blows different arias on a pipe, such as is performed in Provence, and is the heaviest blowing instrument, as well as touching the drum with one hand, also blowing like a living person. The 3rd figure is a duck, made of gold-plated brass and steel, which imitates all the movements a living duck makes, the food and the like of itself. Drinking, swallowing, digesting, and again, like a good droppings, no less flaps the wings up, under and to the side, curses and does everything that a natural duck can do. It is impossible to close everything so precisely describe when it is actually in the work and shows itself in the work, therefore only this is added, that on a single duck = wing there are 400 parts and special dissections. Whoever wants to see this machine, which imitates nature, is open every day in the afternoon at 3 and 5 a.m. for a fee of 36 kr. in the front = and 18. kr. in the back seat; between this time one is respectful to the inner structure, etc. Composition of their machines, in addition to a small interpretation to show what each person, when an adequate number is available, 36. kr. especially to be shot; Standes = people and other noble families will be seen appropriately at any time, in the morning or in the evening, and the renumeration will be left to their own generosity. "

Vaucanson got rich from exhibiting his automatons, but he also became a highly respected member of the Académie des Sciences. The encyclopedists celebrated Vaucanson because he enabled human genius to imitate life. Voltaire says of him: "The bold Vaucanson, opponent of Prometheus , seemed to imitate nature, to take the fire of heaven to animate the bodies."

Later Vaucanson no longer built machines, but became the head of the state silk factories for their mechanization and automation. He gave a strong impetus through further inventions and constructions of his own. “Building automats had been a more amusing than beneficial pastime for several thousand years. Thanks to de Vaucanson's contributions, it was possible to go beyond this stage and use some forms of automatons in industry . Only now did the fruits of the Alexandrian School (see above) ripen so far that an automatically monitored system could become a reality. "

The transition from the 18th to the 19th century

According to Vaucanson, numerous androids , often very complex , that performed real functions were built. The most famous are probably the machines used by father and son Jaquet-Droz. His father, Pierre Jaquet-Droz , born in 1721 and coming from a watchmaking family, designed and built, together with his son Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz and his "mechanic" Jean-Frédéric Leschot, around 1770 the three automatic machines that made him famous and well are among the most beautiful machines ever. For more than a century, the androids toured Europe and could be viewed for an entrance fee. They are still functional today and can be viewed in the museum in Neuchatel , Switzerland.

The writer is z. B. 70 cm high, has a goose feather in his hand, sits in front of a small table and has movable eyes and head. He can write any text up to 40 letters long. The text is coded on a wheel, where the letters are then processed one after the other. When it is started, he first dips the pen into the ink and gently shakes it off, then he writes, paying attention to the upward and downward strokes like a real writer and also taking them down. He can write on multiple lines and respects spaces.

One can see in this machine a forerunner of the computer, because the machine has a program and a memory and can be programmed in different ways (any text can be written).

In addition to the Jaquet-Droz machines, there were many other machines at the end of the 18th / beginning of the 19th century. These machines were lovingly made one-offs, took thousands of hours to make and were accordingly expensive. One of the master designers of the time was Johann Nepomuk Mälzel , who constructed numerous music automatons, including the trumpeter , which was highly praised in the international press at the time , and who was often played for hours from an apartment window in Vienna to amuse the audience. Renowned composers such as Jan Ladislav Dusík and Ignaz Pleyel composed concert pieces for this trumpeter .

Further masters of the automatons were Johann Gottfried Kaufmann and his son Friedrich Kaufmann , who also developed a trumpeter in Leipzig and refined Mälzel's invention even further. In Paris, in 1810, the "organ maker Beaudon" created a mechanical elephant that could eat and drink and consisted of 4,800 parts: "There are 3 Indians on its back, making music."

1800–1850 - The era of the magician-technician

A large number of machine manufacturers in the first half of the 19th century were magicians or otherwise inspired by illusion art that was very fashionable at the time.

Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin , the father of modern magic , came from a family of watchmakers and constructed a large number of real automatons, which he presented in a special theater. At the same time, he also developed trick machines that - invisible to the public - were controlled with cables or pedal systems either from the outside or by living beings hidden in the object, e.g. B. the pastry chef of the Palais Royal or Antonio Diavolo, the trapeze artist.

Stèvenard, French magician, mechanic and contemporary of Robert-Houdin, was perhaps the most talented precision mechanic among the automaton builders of the time, because he built very small and nevertheless extremely complex automatons, which he presented in a Paris automat theater around 1850. There were e.g. For example, a magician who runs a 10-minute program in which objects keep disappearing and new ones appear, with birds "the size of a fly".

The Maillardet brothers are known for their magicians and other pendulum diviners. Jacques-Rodolphe, Henri and Jean David, of rural origin, were always overshadowed by the Jaquet-Droz family, whose apprentices but also suppliers of bird mechanisms they were. They lived in a small village called Fontaine. Between 1808 and 1840 they built a whole series of magicians who could answer questions prepared on boards.

1850–1914 - Small machine industry in Paris

The machines described above were still elaborately produced one-offs and correspondingly expensive. While the number of sufficiently wealthy enthusiasts steadily declined at the beginning of the 19th century, the popularity of machines grew at the same time in ever wider circles who would also like to own them. In the 19th century, a modest vending machine industry emerged, especially in Paris. However, this is to be understood in such a way that the pieces produced by some families such as Vichy, Lambert, Decamps, Roullet etc. were no longer unique pieces, but were made very carefully and in small editions.

With the outbreak of World War I , this small industry came to a standstill.

First World War to this day

Many small machines were probably z. B. also made in Germany, such as. B. Songbird machines, which were still made in the Black Forest in the 1970s.

There are still automata - including humanoids - in kinetic art . In the Herbie Hancock video "Rock-It", for example, B. the pneumatically animated humanoid automata by Jim Whiting the main role.

History of the other types of machines

Parallel story: jukeboxes

In parallel to the mostly humanoid automatons (or also animal automatons) described above, music automatons in the form of self-playing musical instruments had long been developed. The drive for the development of self-playing musical instruments was less the desire for invention than the need for music.

The oldest surviving mechanical musical instruments are the carillons in the monumental clocks of the late Middle Ages . During the Renaissance , artisans in Augsburg created valuable music automatons and self- playing spinets that were controlled by pin rollers .

The flute clock was created in the 18th century , for which Haydn , Mozart and Beethoven created original compositions. The demands on the technical and musical possibilities of self-playing instruments increased steadily, and at the beginning of the 19th century so-called "music machinists" like Johann Nepomuk Mälzel constructed entire self-playing orchestras, the "orchestrations" .

Around the same time, music boxes were created in Switzerland , in which the pins of a rotating brass cylinder tore the teeth of a clay comb and made them sound. In the course of industrialization, it later became possible to manufacture inexpensive devices that were affordable for everyone: the “Ariston” and “Herophon” rotary instruments controlled by perforated cardboard disks were sold by the hundreds of thousands. Around 1890 they were replaced by the record music boxes, the best-known brands of which were “Polyphon”, “Symphonion” and “Kalliope”.

With the introduction of pneumatics towards the end of the 19th century, it was possible for the first time to manufacture self-playing pianos that allowed a satisfactory dynamic gradation. The pedal operated "Phonolas" and "Pianolas" belonged to every middle-class establishment.

Electric pianos and huge pneumatic orchestras were built for inns and dance halls, and a self-playing violin, praised as the eighth wonder of the world, delighted music lovers. The hand-held rotating organ from around 1700 was further developed into a powerful carousel and dance organ .

In 1904, Welte & Söhne brought the "Mignon" piano playing apparatus onto the market, which for the first time made it possible to reproduce a pianist's piano playing with all dynamic and agogic details. With the spread of the gramophone and the radio , mechanical musical instruments were increasingly forgotten. However, this does not apply to reproduction pianos , B. manufactured by Bösendorfer since 1986 as a computer grand piano.

Parallel history: service, vending and entertainment machines

The history of this type of vending machine also begins with Heron of Alexandria , who invented the first vending machine. The first modern vending machines appeared in the USA in the mid-19th century. The origin of the German vending machines goes back to the Cologne chocolate producer Ludwig Stollwerck , who saw the first coin-operated machines there during a trip to the USA in 1886. Together with Max Sielaff from Berlin and Theodor Bergmann from Gaggenau, he developed the first vending machine models "Rhenania" and "Merkur" with the patented coin checking system from Max Sielaff. In 1895 Ludwig Stollwerck founded the Deutsche Automaten Gesellschaft Stollwerck & Co. in Cologne, which took over the production, installation, assembly and maintenance of the machines. The machines were a great success for Stollwerck and the product range covered all kinds of items after a short time. The first automatic restaurants were opened around 1900, and they were also very popular.

Vending machines can sell not only goods but also services. Very widespread were z. B. the coin scales invented in 1886, in 1898 the first coin operated telephones were installed. The parking meters , which were first installed in the USA in 1935, are also a service machine.

Entertainment machines, such as For example, the dynamometers, first presented in Germany in 1887, soon became an important part of annual fairs, but also offered relatively inexpensive entertainment on other occasions. The variety was great and ranged from fortune-telling or horoscope machines to electrifying machines. Of course, the image viewers also had an important function, creating the illusion of moving images before the cinema or showing three-dimensional images.

Around 1900 slot machines were also introduced, which at first were purely dexterous devices like the "Bajazzo", where balls had to be caught with a movable catch pocket.

Automatic machines in production and industry

As already mentioned, Vaucanson presented so to speak, the interface between the invention of more scientific-technical interest or for pure pastime and the introduction of machines in the production . After trying it to Prussia poach, he was in 1741 by Cardinal Fleury to Appointed head of state silk mills.

Vaucanson now constructed a mechanical loom for patterned fabrics, the control of which worked on the same principle as that of his flute player. His invention initially had no immediate consequences. In 1804, however , Jacquard reassembled the ruins of this loom and invented his automatic loom in the process.

Vaucanson also practically invented the modern factory . In 1756 he set up a silk spinning mill in Aubenas near Lyon and renovated or reinvented every detail of the building and the drive. This can be seen as "by far the earliest industrial facility in the modern sense" (p. 56). He realized that manufacturing had to take place in a concentrated facility in which every detail was thought out and whose machines were fed by a single power source.

The still existing models of his spinning machines show a striking elegance of the construction and an impressive number of vertically lined up spindles and stand in striking contrast to the clunky constructions that the English used for their cotton spinning machines .

Nevertheless, his efforts were fruitless. Like many other ideas of the 18th century, these too failed to gain a foothold in the Catholic ancien régime in France. The industrialization finally began in England , where completely different sociological conditions were met. Above all, cotton was used instead of silk , which made it possible to sell on a large scale; But the operators of industrialization also came from completely different backgrounds . They were mostly climbers from poor backgrounds instead of aristocrats or established citizens and built their factories in relatively young cities that were not bound by old guild regulations .

Automata in culture

- Hoffmanns Erzählungen (1851), opera by Jacques Offenbach

- The dancing heart (1953), feature film by director Wolfgang Liebeneiner

- The Discovery of Hugo Cabret (2007), children's and youth book by Brian Selznick

See also

literature

- Ralf Bülow: The artificial human being, the unknown being. A short history of automata, androids, golems, robots, homunculi and cyborgs . Series of publications and materials from the Fantastic Library in Wetzlar. Small series, Volume 5, Wetzlar 2016

- John Cohen: Golem and Robot. About artificial people. Look around 1968.

- Peter Gendolla : The living machines. Metro 1980.

- Carsten Priebe: A journey through the Enlightenment : machines , manufactories and mistresses. The Adventures of Vaucanson's Duck or The Search for Artificial Life. BOD, ISBN 978-3-8334-8614-2 , 3rd edition 2008.

- Foundation Schloss und Park Benrath (Ed.): Miracles and Science. Salomon de Caus and the art of automatons in gardens around 1600. Catalog book for the exhibition in the Museum for European Garden Art of the Benrath Palace and Park Foundation, August 17 to October 5, 2008. Düsseldorf 2008, ISBN 978-3-89978-100-7 .

- Helmut Swoboda : The artificial human. Heimeran-Verlag, Munich 1967.

- Klaus Völker : Frankenstein or the modern Prometheus . In: ders. (Ed.): Artificial people. Seals and documents about golems, homunculi, androids and loving statues . Hanser, Munich 1971, ISBN 978-3-446-11486-9 , pp. 426-496.

Web links

- Scholarship Editions : Robert-Houdin and the Vogue of the Automaton-Builders. Detailed article on the history of the automaton, especially Robert-Houdin, Vaucanson, Jaquet-Droz, Kempelen, Maelzel.

- Experience a journey through time through the history of machines in Germany , as of 2013.

- German Automata Museum - Gauselmann Collection Museum for goods and gaming machines in Espelkamp, as of December 4, 2013.

- Automates anciens - German version , as of January 1st, 2008. The English version is better, where all links and films work. It is a commercial website, which is why a notice window appears on the shop!

- Website of the Society for Self-Playing Musical Instruments e. V. , as of December 3, 2011.

- Picture gallery of “Automatomania” , as of September 10, 2012, especially toys - and a. Automata of the 19th century (English).

- Kugelbahn.ch , a huge collection of web links to automata, kinetic art, etc. on, as of December 4, 2013.

- Detlev Knick's private website with old music boxes and songbird machines, as of December 4, 2013.

- Friedrich Kaufmann's mechanical trumpeter in the Deutsches Museum : December 4, 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Sigfrid Giedion: The rule of mechanization. Athenäum Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 1987, p. 65.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Sigvard Strandh: The machine. History - elements - function. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1992, p. 171.

- ↑ Sigvard Strandh: The machine. History - elements - function. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1992, p. 172 f.

- ↑ See Heribert Christian Scheeben: Albertus Magnus. Cologne 1955, p. 200 and 202–204 as well as: Sigvard Strandh: The machine. History - elements - function. Augsburg 1992, p. 173 ff.

- ↑ Such mediaeval reports about "moving statues" are, so to speak, about something like "artificial people", not automatons with a clockwork drive.

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas: Summa theologica I, 115, 5.

- ↑ See also Thomas Linsenmann: The magic with Thomas Aquinas. Berlin 2000, p. 157: "The apparent enlivening of a statue is a magical topos, which of course occurs more in learned theory than in reality."

- ↑ Sigvard Strandh: The machine. History - elements - function. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1992, p. 175.

- ↑ Sigvard Strandh: The machine. History - elements - function. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1992, p. 177.

- ↑ a b c André Soriano (ed.): Mechanical characters from bygone times. Sauret, Paris (?) 1985, p. 40.

- ↑ Sigvard Strandh: The machine. History - elements - function. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1992, p. 177.

- ↑ Augspurgischer Intelligence = Zettel, April 11, 1748, Num. 15, p. 3, as a digital copy.

- ↑ Sigvard Strandh: The machine. History - elements - function. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1992, p. 179.

- ^ Augsburgische Ordinari Postzeitung , Nro. 299, Freytag, December 15, 1809, p. 1.

- ^ Augsburgische Ordinari Postzeitung , Nro. 151, Monday, June 25th, Anno 1810, p. 1.

- ^ TIL Productions SARL: website. ( Memento of January 3, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Paris 2001, as of January 1, 2008 = source for the entire section, here detailed descriptions and illustrations.

- ↑ Detlev Knick: Private website. Berlin, as of January 4, 2008.

- ↑ GSM Society for Self-Playing Musical Instruments e. V .: website. Essen 1997–2005, as of January 1, 2008.

- ^ Uwe Spiekermann: Basis of the consumer society. Origin and development of the modern retail trade in Germany 1850-1914. CH Beck, 1999, ISBN 978-3-406-44874-4 .

- ↑ RWWA, Dept. 208: Stollwerck AG, documents Deutsche Automatengesellschaft, Cologne, (DAG).

- ↑ Gauselmann Collection - German Automata Museum: Website. Espelkamp o. J., as of January 1, 2008.