Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (* around 1820 as Araminta Ross in Dorchester County , Maryland ; † March 10, 1913 in Auburn , New York ) was the best-known African-American escape helper for the Underground Railroad , who helped refugee slaves from around 1849 until the end of the Civil War , to flee from the southern states to the northern states of the USA or Canada .

Harriet Tubman played an exceptional role during abolitionism . After successfully escaping slavery herself in 1849 , she returned to the southern states several times under the code name Moses to help other slaves on their escape. During the Civil War, she worked alongside her work as a nurse and cook as a scout for the northern states. In the later years of her life she became involved in the women's movement .

After her death, Harriet Tubman was largely forgotten, but is now one of the well-known historical figures in the USA. Numerous children's books , which have been published since the 1960s and which in some cases dramatically exaggerate their lives, have contributed to this.

Life

Family background

All that is known about Harriet Tubman's ancestry is that Modesty, her maternal grandmother, was brought to the United States on a slave ship. During her childhood, Harriet Tubman was repeatedly told that she was descended from the Ashanti , a people who are native to what is now the state of Ghana . There is no evidence to confirm or disprove this statement. Nothing is known about the grandfather on the maternal side. It cannot be ruled out that Harriet Green - Harriet Tubman's mother - was conceived by a white man. Harriet Green worked as a cook for the Brodess family and was initially owned by Mary Pattison Brodess. Later it passed into the possession of Edward Brodess, the son of Mary Brodess. In 1808 Harriet Green married the slave Ben Ross, who belonged to Mary Pattison Brodess' second husband, Anthony Thompson. Anthony Thompson owned a large plantation near the Blackwater River in Dorchester County , Maryland . Ben Ross, who was skilled with wood, was responsible for all the carpentry work on this plantation. Judging by court records, the couple had a total of nine children.

According to a previous owner's will, Harriet Tubman's father, Ben Ross, was released in 1840. He continued to work as a foreman for the Thompson family, who had previously owned him as a slave. Harriet Green was also stipulated in a will from the previous owner that she should be released at the age of 45. Unlike the Thompson family, however, the Pattison and Brodess families ignored this disposition when they inherited the slaves. There was no way for a slave to enforce this testamentary provision.

childhood

Harriet Tubman was born as Araminta "Minty" Ross. Neither the year nor the place of birth of Harriet Tubman are certain. The historian Kate Larson assumes a birth in 1822 and concludes this, among other things, from a documented payment of a midwife . Jean Humez, on the other hand, thinks 1820 is the most likely, but also considers 1822 to be possible. Catherine Clinton points out that Harriet Tubman repeatedly gave her year of birth as 1825, while her death certificate lists 1815 as the year of birth and the year 1820 is carved on the headstone. In the documents with which she applied for her war pension, however, Harriet Tubman named both the years 1820, 1822 and 1825, which is an indication that Harriet Tubman also did not know the year of her birth.

Edward Brodess, the owner of Harriet Green after Mary Brodess, sold three of Harriet Tubman's older sisters to other slave owners. The contact between them and the family was broken. When a slaver from Georgia also wanted to acquire Harriet Tubman's youngest brother, Moses, Harriet Green hid her son for over a month with the help of other slaves and free blacks. Eventually there was an open confrontation between Edward Brodess and Harriet Green. When Edward Brodess and the Georgia merchant went to the slave quarters to grab the child, Harriet Green threatened that she would smash the head of the first to enter her home. Edward Brodess then decided not to sell the child. Several of Harriet Tubman's biographers suggest that this incident contributed significantly to Harriet Tubman's belief that resistance is possible and worthwhile.

Since Harriet Tubman's mother worked in the manor house, she had few options to look after her children. As a small child, Harriet Tubman took care of the younger siblings. At the age of five or six, her owner saw her fit for work and rented her out to other slave owners several times. Her first "loan owner" was a woman named "Miss Susan," who was employed by Harriet Tubman to look after a baby when it slept in its cradle. When the child woke up and screamed, Harriet Tubman was whipped for it. Harriet Tubman later reported that she remembered one day when she was punished this way no less than five times before breakfast. She still bore the scars from these punishments at the end of her life. When she faced another punishment for stealing some sugar, she hid in a neighbour's pigsty for five days until hunger forced her to return to Miss Susan's house. While on loan to the plantation owner James Cook, she had to check the traps set for muskrats in the nearby swamps . Even being infected with measles was no reason to relieve her from this work, which, among other things, forced her to wade through water that came up to her waist . When she finally became so seriously ill that she was unable to work, she was sent back to her owner. Shortly after her mother nursed her back to health, she was rented out again to various slave owners for plantation work. Harriet Tubman later reported that she was mostly homesick during this time and once compared herself to the boy on the Swanee River , a reference to Stephen Foster's ballad Old Folks at Home . As she got older, the tasks assigned to her became more physically demanding. They were used in forest work as well as on the plantation fields, where plowing or leading the team of oxen were part of their typical tasks.

The head injury

As a teenager, Harriet Tubman suffered a serious head injury that would affect her for the rest of her life. She had been sent to a store to buy supplies. There she met a slave from another family of plantation owners who had gone away from working in the fields without permission. His incoming overseer asked Harriet Tubman to help him tie up the slave. When she refused and the slave ran away, the guard grabbed a two-pound weight from the counter and threw it at the slave, but missed the target and hit Harriet Tubman in the head instead. She later said it broke her skull and attributed it to her thick hair that she survived in the first place. She was taken back to the plantation where she was working at the time of the incident, unconscious and bleeding. She was left on a loom bench for two days with no further medical treatment. Then she was sent back to work in the fields. Blood and sweat still ran down her face so that she could barely see, Harriet Tubman later described it herself. On the grounds that she was not worth a penny, her loaner finally sent her back to Edward Brodess, who tried unsuccessfully to sell them.

The head injury comes at a time when Harriet Tubman was developing into a religious person. Her mother had told her stories from the Bible when she was a child. However, Harriet Tubman rejected the interpretation of the Bible by the white slave owners, who read from the writings of the Bible above all the slave's duty to obedience. She preferred the Old Testament tales of revenge and retribution. After the head injury, Harriet Tubman began to have increasingly hallucinations and very vivid dreams , which she regarded as a sign from God until the end of her life. She was repeatedly passed out for long periods of time, although she later claimed that she was always aware of her surroundings. Her biographer Kate Larson suspects that Harriet Tubman suffered from narcolepsy as a result of the head injury .

marriage

Harriet Tubman married the free black John Tubman around 1844. Little is known about her husband and the time of their marriage. In any case, the connection was complicated because of their slave status. The legal status of the mother determined the legal status of her children, so that all descendants from this marriage would also have been slaves. Marriage between free and slave was common on the east coast of Maryland. In this region, over half the black population was free, and many African-American families were made up of free and enslaved members. Harriet Tubman's biographer, Kate Larson, suspects that the marriage was planned for John Tubman to buy his wife out at the first opportunity. Around the time of the marriage she changed her first name "Araminta" or "Minty" to Harriet . Kate Larson believes this happened immediately after the marriage, while Catherine Clinton believes the change of first name only happened after Harriet Tubman had concrete plans to escape from slavery.

The first attempt to escape

In 1849 Harriet Tubman fell ill again, which significantly reduced her value as a slave. Edward Brodess then tried to sell them, but could not find a buyer. Harriet Tubman responded to these attempts to sell with prayers to God asking that he bring Edward Brodess to understand: “I prayed for my Lord through the night through March 1st and all the while he was bringing people to look at me who should buy me. ”When it appeared that Edward Brodess had found a buyer in early March 1849, she changed her prayers and asked God to kill Edward Brodess. Edward Brodess died a week later, causing Harriet Tubman to repent over her prayers. In fact, Edward Brodess's death increased the likelihood that Harriet Tubman would be sold to another plantation owner and her family torn apart. His widow Eliza began to dissolve the property and in this context also to sell the family's slaves. Harriet Tubman didn't want to wait to see what plans the Brodess family had about her. Although her husband tried to dissuade her, Harriet Tubman decided to flee north.

Harriet Tubman and her brothers Ben and Henry escaped on September 17, 1849. Harriet Tubman was sent to Dr. Anthony Thompson, who owned a large plantation in neighboring Caroline County. It is very likely that her brothers worked for Anthony Thompson there too. Therefore, there is a high probability that Eliza Brodess did not notice for some time that three of her slaves had escaped. It wasn't until two weeks later that she placed an ad in the Cambridge Democrat promising up to 100 US dollars in rewards for bringing back one of the runaway slaves. However, the three siblings returned voluntarily: no sooner had they left for the north than Harriet Tubman's brothers began to doubt their decision. Ben had just become a father and both brothers were concerned about the dangers that lay ahead. Harriet Tubman was forced to return with them.

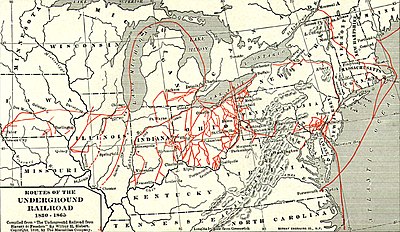

The escape to Pennsylvania

A little later, Harriet Tubman escaped again, this time without her brothers. Her family tried to inform her that she was trying to escape again by singing a song in the presence of another slave she trusted, which contained a hidden farewell message: I'll meet you in the morning, I'm bound for the promised land ("I'll meet you in the morning, I'm going to go to the promised land"). Harriet Tubman's exact escape route is unknown. Since other slaves also used this escape route, Harriet Tubman gave details towards the end of her life. Even so, many details remained unknown. It is known that she used the network of escape workers known as the Underground Railroad . This informal but well-organized association consisted of free blacks and white opponents of slavery. Among the most important active white opponents of slavery were members of the Religious Society of Friends , also known as Quakers . In the Preston area near Dr. Anthony Thompson lived a very large Quaker community and it is likely that Harriet Tubman found shelter here. From there she probably took an escape route that was also used by many other slaves: this route led in a northeasterly direction along the Choptank River , then through the US state of Delaware to Pennsylvania . This escape route was about 145 kilometers long; on foot it took between five days and three weeks. Harriet Tubman covered a large part of the route at night and used the Pole Star as a guide. A constant danger were slave catchers, who caught escaped slaves in order to collect the rewards offered for them. Escape at night reduced the risk of being discovered and taken by them. The Underground Railroad escape workers also resorted to a number of tricks to protect those fleeing from detection. In one of the households in which Harriet Tubman found shelter at the beginning of her escape, the landlady had her sweep the yard; this gave the impression that she was working for the family. After dark, the family hid her on a cart and took her to the nearest shelter. Since Harriet had been sent to work on other plantations since childhood, she was familiar with the forests and swamps of the region; she probably hid there during the day. Years later, Harriet Tubman described her feelings when crossing the border into Pennsylvania :

“When I realized I had crossed the line, I looked at my hands to see if I was still the same person. It was all so wonderful; the sun shimmered like gold through the trees and over the fields and I felt like I was in heaven. "

"Moses"

Immediately after Harriet Tubman settled in Philadelphia , she began to long for her family. She later reported about this time:

“I was a stranger in a strange land. My father, mother, brothers, and sister were [in Maryland]. But I was free and they should be free too. "

She took on a number of different jobs and began saving money. By now, however, the United States Congress had passed the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 . Even in the US states that had declared slavery unlawful, the executive branch now had to assist in the apprehension of escaped slaves. Anyone who helped slaves escape would face severe penalties. Escaped slaves who had settled in states where slavery was illegal could no longer feel safe there. Many of them moved further north to settle in Canada .

In December 1850, Harriet Tubman learned that her niece Kessiah was going to be sold with her two young children, six-year-old James Alfred and baby Araminta. Horrified at the idea that this part of her family should be separated, Harriet Tubman returned to Maryland. This voluntary return to help other slaves on the run, with which Harriet Tubman took the risk of being recognized and turned over to her previous owners, sets Harriet Tubman apart from most other escape workers on the Underground Railroad.

In Baltimore, she hid in the house of her brother-in-law, Tom Tubman, until the slave auction was due, in which Kessiah and her children were to be auctioned. Kessiah's husband, a free black man by the name of John Bowley, made the highest bid for his wife and actually won the bid. While he pretended to make arrangements for the purchase price to be paid, Kessiah and her children fled to a so-called safe house , one of the households that offered shelter to fleeing slaves. After dark, John Bowley took his family in a wooden boat to Baltimore, 100 kilometers away, where they met Harriet Tubman, who took the entire family to Philadelphia.

The following spring, Harriet Tubman returned to Maryland again to lead more members of her family to freedom. This time she accompanied her brother Moses and two other men, whose identities are unknown, to freedom. It is likely that Harriet Tubman worked primarily with the white anti-slavery opponent and Quaker Thomas Garrett , who lived in Wilmington, Delaware, in these first escape aids . The news of the successful escapes encouraged her family to consider escaping as well. Harriet Tubman's biographers, Kate Larson and Catherine Clinton, also note that she gained courage and confidence with each trip back to Maryland. The successful escapes made Harriet Tubman known under the name "Moses" - an allusion to the prophet Moses , who according to the Old Testament led the Hebrews out of Egypt to freedom. Occasionally one reads that the spiritual Go down Moses refers to Harriet Tubman. Folklorist Harold Courlander thinks it is quite possible that a number of slaves interpreted this spiritual in this way. But he also points out that many of the slaves living on plantations must have been unfamiliar with the name Harriet Tubman due to their semi-isolation and that this spiritual theme had a purely religious theme for them.

In the fall of 1851, Harriet Tubman returned to Dorchester County, Maryland for the first time since her escape. Her goal was to find her husband John and return to Philadelphia with him. However, John had meanwhile married another woman. When Harriet Tubman sent him the message that she was there to take him north, he refused on the grounds that he was happy where he was now. Harriet Tubman wanted to confront him first, but then refrained from doing so because she finally came to the conclusion that he was not worth the trouble. Instead, she brought another group of slaves to Philadelphia. John Tubman, who was raising a family with his second wife, was killed 16 years later in an argument with a white man.

Helpers and escape routes

In eleven years, Harriet Tubman returned to the east coast of Maryland a total of 13 times. From there she personally led about 70 slaves to Pennsylvania. Among those who were liberated were their other three brothers, Henry, Ben and Robert, their respective wives and some of their children. She gave instructions to another fifty to sixty refugees on the best routes to get north. Her dangerous work required a great deal of ingenuity. She increasingly used the winter months to lead groups into freedom, because the longer nights were less likely that her group would be seen. When the group that would flee north with her was determined, they usually left on Saturday evening, since the newspapers announcing their escape would not appear until Monday. With the help of previously agreed gospel songs, she signaled to her fellow travelers whether there was any danger or whether they could safely move out of their hiding spots.

Harriet Tubman was in constant danger in Maryland of being recognized by one of the white men she had worked for as a slave. She once escaped discovery by a previous employer while on a train ride because she was able to hide behind a newspaper. In order to appear as inconspicuous as possible, she wore a hood and two live chickens under her arm as headgear on another trip. This was supposed to give the impression that she was a house slave who was getting something for her owner. When she realized that a white man she had once worked for was walking right up to her, she tore the string that tied the chickens' feet. Pretending to calm the chickens down, she managed to keep him from looking her in the face.

In an 1897 interview with author Wilbur Siebert, Harriet Tubman gave some of the details of her work for the Underground Railroad . She found refuge several times with Sam Green, a free black preacher who lived in East New Market , Maryland. She repeatedly hid near her childhood home in Caroline County . From there she traveled northeast to Delaware via Sandtown and Willow Grove to Camden . In Camden, she found support from William and Nat Brinkley and Abraham Gibbs, who each helped her get to Blackbird via Dover and Smyrna . Other Underground Railroad employees helped her cross the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal towards New Castle and Wilmington . In Wilmington the Quaker Thomas Garrett organized the onward journey either to William Still or to the homes of other supporters of the Underground Railroad in the area around the city of Philadelphia. Like Harriet Tubman, the colored William Still is one of the most important personalities of the Underground Railroad. Historians today assume that William Still helped hundreds of fleeing slaves to flee from Philadelphia to the US states of New York, New England or even Canada. Since the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed, the Philadelphia region, which was directly adjacent to the southern states, was no longer a safe area for escaped slaves. In the states further north, the risk that slave catchers would search for escaped slaves was significantly lower . Only Canada was really safe for escaped slaves.

In December 1851, Harriet Tubman brought eleven refugees to Canada for the first time. It is unknown who belonged to this group, but the Bowley family, who brought them to Philadelphia in the fall of 1850, were probably there. There is evidence that makes it very plausible that Harriet Tubman and her group found shelter with Frederick Douglass on their way to Canada . In one of his autobiographies he reports that he once gave shelter to eleven refugees at the same time: “They had to stay with me until I had enough money to go on to Canada. It was the largest group I had ever hosted and I had problems providing so many with food and space… ”Both the number of refugees and the timing make it very likely that this was Harriet Tubman's group.

Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman showed great respect for one another. In 1868 Frederick Douglass wrote her a letter explaining why he valued her work so highly:

“You ask for what you do not need when you call upon me for a word of commendation. I need such words from you far more than you can need them from me, especially where your superior laboratories and devotion to the cause of the lately enslaved of our land are known as I know them. The difference between us is very marked. Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day — you in the night. ... The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism. Excepting John Brown — of sacred memory — I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have. "

“When you asked me for a recommendation, you asked me for something that you don't need. I need your recommendation much more than you need mine - especially because your outstanding work and your commitment in the fight for the enslaved in our country is as well known to everyone as I am. The difference between us is vast. Most of what I've done [...] has been done in public and I've received a lot of support in everything. You, however, worked in silence. I fought during the day and you at night […] Only the night sky and the silent stars were witnesses of your struggle for freedom and your courage. Apart from John Brown [...] I don't know anyone who has voluntarily taken on so many dangers and privations to help our enslaved fellow human beings. "

Harriet Tubman's religiosity was an essential source of strength for her to make the dangerous journey to Maryland repeatedly. The hallucinations she suffered from since her head injury were for her a sign of divine providence. She was deeply convinced that God would keep her safe. The Quaker Thomas Garrett said of her: "I do not know any other person, regardless of skin color, who had so much faith in the voice of God". She carried a revolver with her on her travels and was not shy about using it. Slaves who wanted to return to their owners after they had started to flee represented a high risk for the rest of the refugees because they could reveal who helped them escape and how to escape. Harriet Tubman later reported that the only way to prevent a fugitive from returning was by holding the pistol to his head and threatening to shoot him. The weapon was also protection from slave catchers and their vicious dogs.

Harriet Tubman's bounty?

Little did the slave owners on the east coast of Maryland realize that the runaway, physically small and disabled female slave Minty had been involved in so many successful attempts by slaves to escape. Instead of Harriet Tubman, they suspected in the late 1850s that a white anti-slavery was bringing their slaves north. In the meantime they even considered the possibility that the “white” activist and militant anti-slavery opponent John Brown was now active on the east coast. The alleged $ 40,000 bounty allegedly on offer for the arrest of Harriet Tubman, and which is occasionally read about in connection with Harriet Tubman to this day, was in fact never promised. The origin of this rumor is known: In 1868 a slavery opponent by the name of Salley Holley tried to get Harriet Tubman to get a pension and wrote a newspaper article for this purpose. In it, she wrote that for the Maryland slaveholders, $ 40,000 for the arrest of Harriet Tubman was not too high. How unrealistic this number is is shown by the purchasing power of this sum and its comparison with other rewards. At that time you could already buy a small farm for 400 USD. The US federal government set aside 25,000 US dollars each for the capture of the Abraham Lincoln assassins . If Harriet Tubman had ever had a $ 40,000 bounty, it would have made headlines across the United States because of its unusual size. However, there is no evidence of this sum or of the alleged 12,000 US dollars, which is also occasionally mentioned as a reward for the capture of Harriet Tubman.

In all of her tenure as an escape agent on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman was never apprehended, nor was any of the slaves who took her north. Years later, in a speech about herself, Harriet Tubman said:

"I was a conductor on the Underground Railroad for eight years and I can say what few other conductors can say - I never derailed my train and I never lost any of my passengers."

John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid

On one of her last trips in 1857, Harriet Tubman took her parents north. Her father, Ben Ross, was able to buy Harriet Green from Eliza Brodess for twenty dollars in 1855, so that both of them now had the status of free blacks. However, Ben Ross had given shelter to escaped slaves, so that the couple was in danger of being arrested. Harriet Tubman brought her to St. Catharines, Canada, where several of Harriet Tubman's relatives now lived.

In April 1858, Harriet Tubman was introduced to John Brown . He was one of those opponents of slavery willing to use force to end slavery in the United States. Like Harriet Tubman, John Brown felt called by God to act against slavery and trusted that God's protection would protect him from the slaveowners' acts of revenge. Harriet Tubman was convinced that she had foreseen the meeting with John Brown in a prophetic vision.

At the time of their first meeting, John Brown was busy planning an attack on slave owners. Other opponents of slavery such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison thought little of his plan to create a separate state for freed slaves through fighting. John Brown, on the other hand, was convinced that the first violent confrontations would lead to uprisings among the slaves that would extend across the entire southern states of the United States. "General Tubman", as he called Harriet Tubman, was one of his essential supporters because of her knowledge of the circumstances and potential supporters in the border area of the US states of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware. On May 8, 1858, John Brown held a meeting in Chatham-Kent, Ontario, where he first gave details of a raid on Harpers Ferry, West Virginia . The plan was not kept secret, however. John Brown therefore had to postpone the project and used this time to raise funds. Harriet Tubman assisted him both in his fundraising efforts and in devising a more detailed plan for the attack on Harpers Ferry.

At this point Harriet Tubman was mainly busy speaking at meetings of anti-slavery opponents and taking care of her relatives. In the fall of 1859, when John Brown and his men carried out their attack, Harriet Tubman was absent. Some historians believe she was in New York at the time and was ill. Other historians suspect that at the time she tried to persuade slaves who had fled and are now living in Canada to take part in the fight against the slave owners. Kate Larson, on the other hand, thinks it is more likely that she was in Maryland by the time she was either promoting John Brown's plans or trying to get family members to flee north again. Kate Larson also notes, however, that Harriet Tubman may now have shared Frederick Douglass' doubts about the feasibility of the plan.

In fact, the attack on Harpers Ferry failed and the captured John Brown was hanged in December 1859. For many opponents of slavery, his failed attack became a symbol of resistance; he himself was considered a noble martyr . Harriet Tubman praised him to the end of her life and emphasized with the words [H] e done more in dying, than 100 men would in living (translated as "he achieved more through his death than 100 others through their life"), which unifying Effect from his death.

Auburn and Margaret

At the beginning of 1859, the slavery opponent and US Senator William H. Seward Harriet Tubman sold a small piece of land on the outskirts of the city of Auburn in the state of New York for $ 1,200. The town of Auburn was home to many people who were committed to the fight against slavery, and Harriet Tubman felt safe enough there to bring her parents to live with her. But even in Auburn, escaped slaves had to expect to be transferred to their owners on the basis of the Fugitive Slave Law . Harriet Tubman's siblings therefore had serious reservations about this move. Historian Catherine Clinton believes that Harriet Tubman's anger at the so-called Dred Scott decision was the reason she returned to the United States. The house on the outskirts of Auburn became the center of Harriet Tubman's life. She took in both relatives and lodgers there for years and offered shelter to blacks on the way to Canada.

Shortly after purchasing her home in Auburn, Harriet Tubman returned to Maryland one more time, returning with her "niece" Margaret. So far there is no consensus on the identity of Margaret's parents. Harriet Tubman himself indicated that they were free blacks. The girl left a twin brother and a loving home in Maryland. Margaret's future daughter Alice described the whole thing as “kidnapping”: “She took a child away from the security of a good home and brought them to a place where no one cared for them.” Historians Clinton and Larson believe it is possible that Margaret was the biological daughter of Harriet Tubman. Kate Larson points out that the two were unusually close, arguing that Harriet Tubman, who had experienced the grief of a child separated from his mother, did not wantonly tore a family apart. Catherine Clinton also points out the strong similarity between Harriet Tubman and Margaret, which Alice, Margaret's daughter, also admits. However, there is no concrete evidence for this hypothesis.

In November 1860, Harriet Tubman traveled to Maryland one last time to help slaves escape. During the 1850s, Harriet Tubman failed to get her sister Rachel and her two children to the northern United States. On her return to Dorchester County in 1860, she learned that Rachel had since passed away. However, Harriet Tubman could only have managed the escape of her two enslaved children, Ben and Angerine, with a bribe of USD 30. She did not have the money, so she had to leave the children behind. Her later fate is unknown. Instead, Harriet Tubman led another group north, with whom she returned to Auburn on December 28, 1860.

The American Civil War

In 1861 the American Civil War began. Harriet Tubman saw a Union victory as an essential step towards the abolition of slavery. Together with opponents of slavery from Boston and Philadelphia, she therefore tried to support the Northern Army through her active cooperation. At the beginning, this consisted primarily of caring for refugees in the camps around Port Royal , South Carolina.

In Port Royal, Harriet Tubman met General David Hunter , a staunch opponent of slavery. He declared all slaves who fled to Fort Monroe as spoils of war and then gave them freedom. He also wanted to form a regiment out of the freed slaves. However, US President Abraham Lincoln was too radical and reprimanded General Hunter for his actions. Harriet Tubman condemned Abraham Lincoln's response and his general unwillingness to end slavery in the United States, on both moral and pragmatic grounds. According to her view of the world, she was firmly convinced that God would only let the northern states win if they ended the injustice of slavery. In Port Royal, Harriet Tubman worked as a nurse and also took care of those with smallpox . The fact that she did not become infected in the process gave further nourishment to rumors that she was under special protection from God. However, their right to be supplied by the field kitchen was also seen as preferential treatment by a number of freed slaves. To avoid tension, Harriet Tubman decided not to. For a living she sold root beer and pies, which she made herself in the evening.

Union troops scout

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln declared the end of slavery in the states that had fallen away from the Union with the Emancipation Proclamation . For Harriet Tubman this was the reason to give even more decisive support to the troops of the Union and she began to work for them as a scout. She initially belonged to a group that (on behalf of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ) was to explore and map the area around Port Royal, which was still occupied by the Confederates. The marshes and rivers of South Carolina resembled those of the east coast of Maryland, and their skills and experience in navigating such an area were invaluable. A little later she worked as a scout for Colonel James Montgomery and provided him with information that was essential for the successful conquest of Jacksonville , Florida.

Harriet Tubman also played an essential role as a scout during the attack by James Montgomery and his troops on a number of plantations along the Combahee River . On the morning of June 2, 1863, Harriet Tubman led three steamers with Union troops on board through the mined course of the Combahee River. As soon as they were on land, Union forces set the plantations there on fire, destroyed the infrastructure and stolen thousands of dollars' worth of food. The whistling of the steamers was taken by the slaves along the shore as a sign to flee. Harriet Tubman later described how, in that chaotic moment, women fled aboard the ship with steaming rice pots in their hands and sacks of creaking piglets slung over their shoulders while their young children clung to their necks. Their owners tried to prevent the mass exodus with the force of the whips and guns, but their efforts were almost unsuccessful in the turmoil. At the moment the Confederate troops rushed up, the steamships cast off for Beaufort , South Carolina .

More than seven hundred slaves were freed through what is known as the Combahee River Raid . Newspaper articles extolled Harriet Tubman's patriotism and energy, and highlighted how successfully she campaigned among newly freed slaves to join Union forces. After the successful attack on the Combahee River plantations, she worked for Colonel Robert Gould Shaw during the attack on Fort Wagner . According to legend, she was the one who brought him his last meal. Harriet Tubman later described the costly battle for Fort Wagner with the words:

“And then we saw lightning and it was the guns, and then we heard thunder and it was the cannons, and then we heard rain falling and it was the drops of blood, and when we went to get the fruit it was dead Men we reaped. "

Harriet Tubman worked for the Union forces for two more years. She took care of newly freed slaves, scouted the regions still ruled by Confederate troops, and ended up working as an unskilled nurse in Virginia. She returned to Auburn at intervals during this time to look after her family. Even after the end of the Civil War, she remained in the service of the troops for a few months before finally returning to Auburn. Harriet Tubman never received regular wages during this period. In the following years, too, she was initially denied any compensation or pension. Their unofficial status made it difficult to document their work for the troops, and it took US government agencies a long time to recognize them. It wasn't until 1899 that Harriet Tubman received a pension for her services in the civil war that ended in 1865. Since she lived in great poverty, her difficulties in obtaining an official pension were particularly painful for her.

The years after the civil war

Harriet Tubman lived the rest of her life in Auburn, caring for her family and other people in need. She earned a living for herself and her parents in a number of different jobs. She also rented out rooms in her house. One of her subtenants was Nelson Davis, a civil war veteran who worked as a bricklayer in Auburn. The two fell in love, and although he was 22 years younger than Harriet Tubman, they married on March 18, 1869. In 1874 they adopted a toddler named Gertie together.

Harriet Tubman found financial support from people she knew from her time fighting slavery. Sarah H. Bradfort wrote her first, 132-page biography, which appeared in 1869 under the title Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (Scenes from the Life of Harriet Tubman). The sale of the book grossed Harriet Tubman approximately $ 1,200. Even if the book is very subjective from today's perspective and Sarah Bradfort took a number of artistic freedoms, it is still an important source on the life of Harriet Tubman. Sarah H. Bradfort published another volume in 1886 under the title Harriet, the Moses of her people (Harriet, the Moses of her people). One of the goals of this publication was to ease Harriet Tubman's financially strained situation.

Because of her debts - including falling behind on payments for her house and property on the outskirts of Auburn - Harriet Tubman was the victim of a hoax. Two men named Stevenson and John Thomas claimed they had gold in their possession that they had smuggled out of South Carolina. They offered this treasure to Harriet Tubman, which they claimed was worth $ 5,000, for a cash payment of $ 2,000. They gained their trust, among other things, because they said they knew one of Harriet Tubman's relatives and she lodged them in her house for a few days. Harriet Tubman was aware that in the southern states there were many white valuables buried as Union forces approached. It was often blacks who were charged with digging pits. The story was therefore entirely plausible and her financial bottleneck and a certain good faith ensured that Harriet Tubman got involved in the trade. She borrowed the money from a wealthy acquaintance. As soon as the two men had lured Harriet Tubman into a forest to allegedly surrender the gold, they attacked her, stunned her with chloroform and stole her money. The New York state public reacted with indignation to the incident and while some blamed Harriet Tubman for her naivete, many sympathized with her for her financial hardships. The incident also reminded the public of her achievements during the Civil War, for which she had not received any compensation. Gerry Whiting Hazelton , a member of the US House of Representatives from Wisconsin , tried to get Harriet Tubman to make a special payment of USD 2,000 to compensate her for her services as a scout, spy and nurse in the service of the Union troops. The proposal was rejected.

The American women's rights movement

Harriet Tubman turned increasingly to the women's rights movement in her later years, working with prominent US women's rights activists such as Susan B. Anthony and Emily Howland . She campaigned for women to vote at events in New York, Boston and Washington, DC, among others . She described her activities during and after the Civil War and argued that the dedication and willingness of many women to make sacrifices had shown that they were equal to men. When the National Federation of Afro-American Women was founded in 1896, Harriet Tubman was the main speaker at the first meeting. These activities ensured that Harriet Tubman came back into the public eye. A magazine called "The Woman's Era" published a series of articles about influential women and dedicated an article to Harriet Tubman. A women's rights newspaper covers a series of receptions in Boston honoring Harriet Tubman and her service to the United States. As before, Harriet Tubman had little money and had to sell a cow in order to be able to afford the train ticket to travel to these celebrations.

Sickness and death

At the turn of the century, Harriet Tubman became increasingly involved in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Auburn. In 1903 she donated a part of her property to the church with the condition that a home for old and destitute colored people be built on it. It took five years for the home to open, however, and Harriet Tubman was also annoyed that the home's church sponsor had stipulated that future home residents should pay an admission fee of USD 100. Although that contradicted her donation, she was the guest of honor when the Harriet Tubman Home for the old opened on June 23, 1908.

Harriet Tubman still suffered from the effects of the head injury she sustained as a teenager. As early as the late 1890s, she had undergone an operation at Boston's Massachusetts General Hospital because she could no longer sleep because of the pain and the constant "buzzing" in her head. According to her own statements, the top of her head was lifted, which gave her considerable relief. In 1911 she was so physically frail that she had to move into the home she had donated. A New York newspaper described her as ill and destitute, which led to a number of admirers sending her money again. Surrounded by friends and family members, Harriet Tubman died at the age of about 93 on March 10, 1913 of complications from pneumonia.

Posthumous honors and national awareness

After her death, Harriet Tubman was buried with military honors in Fort Hill Cemetery, Auburn. The city of Auburn placed a plaque on the courthouse in their memory. While the plaque expresses pride that such a prominent person was a citizen of the city of Auburn, it has drawn criticism that the plaque quoted Harriet Tubman in incorrect English. The quotation I nebber run my train off de track reproduced on it , which was probably preferred to the more correct I never run my train off the track because of its greater authenticity , is no longer considered politically correct and has been criticized because it is its reputation as a US -American patriot and staunch humanist. At least Booker T. Washington was the keynote speaker at the memorial service for the plaque's installation. Founded by Harriet Tubman, the retirement home was abandoned after 1920 but was later renovated by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and now serves as a museum and educational center.

After the two biographies of Sarah Bradford, it was not until 1942 that another one, addressed to an adult audience, appeared. Numerous versions of Harriet Tubman's life, some of which were dramatically exaggerated, had previously appeared for children. However, Earl Conrad wanted his biography to meet scientific requirements. It took him four years to find a publisher for the book called Harriet Tubman: Negro Soldier and Abolitionist ("Harriet Tubman: Negro soldier and slavery opponent"). Despite Harriet Tubman's fame, it took more than sixty years before serious biographies about Harriet Tubman appeared again. Jean Humez published a book in 2003 that took up some of the life stories of Harriet Tubman. The two biographies of the historians Kate Larson and Catherine Clinton were published in 2004.

According to a survey carried out in the United States at the end of the 20th century, Harriet Tubman is still one of the most famous personalities in American history. Only Betsy Ross and Paul Revere are better known. She was a role model in the struggle for civil rights for generations of African Americans. Politicians from all political camps have honored them in speeches. Dozens of schools bear her names in memory of Harriet Tubman; in addition to the Harriet Tubman Home in Auburn, the Harriet Tubman Museum in Cambridge also commemorates her. In 1944 a US Navy Liberty freighter , the SS Harriet Tubman , was baptized in her name. She was the first black woman to be honored in this way. The feminist group Combahee River Collective , which criticized racism within the women's movement in the 1970s, named itself after the slave liberation organized by Harriet Tubman.

Harriet Tubman was included in the Daughters of Africa anthology published in 1992 by Margaret Busby in London and New York.

In 1978 the United States Postal Service commemorated Afro-American personalities with a series of stamps. The first stamp in the series bears the portrait of Harriet Tubman. In the same year NBC showed the two-part film A woman called Moses with Cicely Tyson in the lead role.

In 1994, a Venus crater on the northern hemisphere of the Venus was named after Harriet Tubman : Venus Crater Tubman . In 2014, at the suggestion of a team from astrophysicist Carrie Nugent, an asteroid in the main outer belt was named after Harriet Tubman: (241528) Tubman .

By April 2016, millions of citizens took part in a survey conducted by Treasury Secretary Jack Lew as to who should appear on the newly designed $ 20 bill. Before that, Tubman won a vote by the non-profit organization Womenon20s with 118,328 votes in front of Wilma Mankiller , Eleanor Roosevelt and Rosa Parks . In 2016, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew announced that in 2020 the new $ 20 bill would feature Tubman's portrait. Tubman would be the only woman on the front of a dollar bill. However, the future finance minister Steven Mnuchin postponed his predecessor's plan in August 2017 after Donald Trump ridiculed it as "pure political correctness". Mnuchin questioned whether people should continue to be depicted on redesigned US dollar bills. In May 2019, Mnuchin announced that the issue of $ 20 bills bearing the Tubman portrait had been postponed to 2028, a time when Trump would no longer be in office. On January 25, 2021, 5 days after his inauguration as president, Joe Biden revived the plan to recreate the portrait of the controversial 7th President of the United States, Andrew Jackson , for slave possession and crimes against indigenous people, according to press secretary Jen Psaki Replacing portrait of Harriet Tubman.

In the Episcopal Calendar of the United States of America , July 20th is a day of remembrance for Harriet Tubman and March 10th is a memorial day for the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) .

In autumn 2019, the film adaptation of her story was released under the title Harriet . The director took Kasi Lemmons , in the lead role is Cynthia Erivo to see.

literature

- Anna-Maria Benz: "Freedom or Death" - Harriet Tubman 1820–1913, Afro-American freedom fighter . Edition AV , Lich 2009 ISBN 978-3-86841-022-8 .

- Sarah Bradford : Harriet Tubman: The Moses of Her People . Corinth, New York 1961, new edition. the edition of 1886 LCCN 61-008152 .

- Sarah Bradford: Scenes in the life of Harriet Tubman . WJ Moses, printer. Auburn NY, 1869. New edition: Books for Libraries Press, Freeport 1971 ISBN 0-8369-8782-9 .

- Catherine Clinton : Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom . Little, Brown and Company, New York ISBN 0-316-14492-4 .

- Earl Conrad : Harriet Tubman: Negro Soldier and Abolitionist . International Publishers, New York 1942 OCLC 08991147 .

- Frederick Douglass: Life and times of Frederick Douglass: his early life as a slave, his escape from bondage, and his complete history, written by himself . Park Publishing Company, Hartford 1882. Reprinted by Collier-Macmillan. London 1969 OCLC 39258166 .

- Jean Humez: Harriet Tubman: The Life and Life Stories . University of Wisconsin Press, Madison 2003 ISBN 0-299-19120-6 .

- Kate Larson : Bound For the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero . Ballantine, New York 2004 ISBN 0-345-45627-0 .

- Milton C. Sernett: Harriet Tubman: Myth, Memory and History . Duke University Press, Durham 2007 ISBN 978-0-8223-4073-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Harriet Tubman in the catalog of the German National Library

- Harriet Tubman. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- Original text by Sarah Bradford: Harriet Tubman: Moses of Her people in the Gutenberg project

- Detailed webpage by Kate Larson about Harriet Tubman

- Slaves, freedmen spied on South during Civil War

- Harriet Tubman: Online Resources , Library of Congress (English)

- Marc von Lüpke: US icon Harriet Tubman: Moses als Fluchthelferin In: one day , September 6, 2013.

- Bernd Becker: Short article in kirche-im-wdr.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Clinton, p. 5

- ↑ a b c Larson, p. 10

- ↑ Clinton, p. 6

- ↑ a b Humez, p. 12

- ↑ Clinton, p. 12

- ↑ Larson, pp. 311-312

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 23-24

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 28-29

- ^ Larson, p. 16

- ↑ Clinton, p. 4

- ↑ Clinton, p. 10

- ↑ Larson, p. 34

- ↑ a b Larson, p. 47

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 13

- ↑ Humez, p. 14

- ↑ Humez, p. 13

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 17-18

- ↑ Larson, p. 40

- ↑ a b Larson, p. 38

- ^ Larson, p. 56

- ↑ a b c Larson, p. 42

- ↑ Clinton, p. 22

- ↑ Clinton, p. 20

- ↑ Larson, pp. 42-43

- ↑ a b Larson, p. 62

- ^ Larson, p. 63

- ↑ Clinton, p. 33

- ^ Larson, p. 72

- ↑ Clinton, p. 31

- ↑ a b Quoted in Bradford (1971), pp. 14-15

- ^ Larson, p. 73

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 31-32

- ↑ Larson, pp. 74-77

- ↑ Larson, p. 77

- ^ A b Larson, pp. 78/79

- ↑ a b Larson, p. 80

- ↑ a b Quoted in Bradford (1971), p. 19

- ^ Larson, p. 82

- ^ Larson, p. 81

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 37

- ↑ Clinton, p. 38

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 37-38

- ^ Larson, p. 83

- ↑ In the original the quote is: 'When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven. '

- ↑ Quoted in Bradford (1971), p. 20; In the original English quote, the "she" is also emphasized.

- ^ Larson, p. 88

- ↑ Clinton, p. 60

- ↑ Larson, pp. 89-90

- ↑ a b c Larson, pp. 90/91

- ↑ Clinton, p. 82

- ↑ Clinton, p. 80

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 85

- ↑ Harold Courlander: A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore , Crown Publishers, New York 1976, ISBN 0-517-52348-5 , pp. 307-308

- ↑ a b c Larson, p. 239

- ↑ Larson, p. XVII

- ^ Larson, p. 100

- ↑ Larson, p. 101

- ^ Larson, p. 125

- ^ Clinton, p. 89

- ↑ Larson, pp. 134-135

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 84

- ^ Douglass, p. 266

- ↑ Quoted in Bradford (1961), pp. 134-135.

- ↑ Clinton, p. 91

- ↑ Quoted in Clinton, p. 91

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 90-91

- ↑ Conrad, p. 14

- ↑ a b Larson, p. 241

- ↑ Quoted in Clinton, p. 192

- ^ Larson, p. 119

- ↑ Larson, pp. 143-144

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 129

- ↑ Larson, pp. 158-159

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 126-128

- ^ Larson, p. 161

- ↑ Larson, pp. 161-166

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 132

- ↑ Humez, p. 39

- ↑ a b Larson, p. 174

- ↑ Quoted from Larson, p. 177

- ^ Larson, p. 163

- ↑ a b c Clinton, p. 117

- ^ Larson, p. 197

- ↑ Quoted from Clinton, p. 119

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 121

- ^ A b Larson, pp. 198/199

- ^ Larson, p. 202

- ^ Larson, p. 204

- ↑ a b Larson, p. 205

- ^ Larson, p. 206

- ↑ a b Clinton, pp. 156/157

- ↑ Larson, pp. 209/210

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 164

- ↑ Clinton, p. 165

- ↑ Larson, p. 212

- ↑ a b Larson, p. 213

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 166

- ↑ Clinton, p. 167

- ^ Larson, p. 214

- ^ A b Larson, p. 216

- ↑ Quoted in Conrad, p. 40

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 186/187

- ^ Larson, p. 180

- ↑ Clinton, p. 188

- ↑ Clinton, pp. 193-195

- ↑ Larson, pp. 225-226

- ↑ Clinton, p. 193

- ↑ Larson, pp. 276-277

- ^ Larson, p. 260

- ↑ Clinton, p. 196

- ^ Larson, p. 244

- ↑ Larson, pp. 264-265

- ↑ a b c Clinton, p. 201

- ^ A b Larson, pp. 255/256

- ↑ Larson, pp. 257-259

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 202

- ↑ Clinton, p. 192 and Larson, p. 287

- ^ Larson, p. 273

- ^ Larson, p. 275

- ^ Larson, p. 281

- ↑ a b Clinton, pp. 209/210

- ^ Larson, p. 282

- ^ Larson, p. 288

- ^ Harriet Tubman , entry in the Find a Grave database (accessed March 10, 2013).

- ↑ Clinton, p. 216

- ↑ Clinton, p. 215

- ↑ Clinton, p. 218

- ↑ Larson, p. XV

- ↑ Larson, p. XX

- ↑ a b Clinton, p. 219

- ↑ US Postal Service, February 21, 2002. Postal Service Celebrates 25th Anniversary of Black Heritage Stamp Series ( Memento of May 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). USPS. Accessed November 13, 2007.

- ↑ The Venus crater Tubman in the Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature of the IAU (WGPSN) / USGS (English)

- ↑ 'Asteroid hunters' search for space rocks that could collide with Earth from a radio show on The Takeaway program on March 15, 2017

- ↑ (241528) Tubman in the Small-Body Database of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of NASA at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena , California (English)

- ↑ Plans reactivated: Harriet Tubman is supposed to be on 20 dollar bill orf.at, January 26, 2021, accessed January 26, 2021.

- ↑ A Woman's Place is on the Money Womenon20s, accessed January 26, 2021.

- ↑ Harriet Tubman will appear on $ 20 bill, leaving Alexander Hamilton on $ 10 theguardian.com, April 20, 2016, accessed January 26, 2021.

- ↑ Ex-slave appears on a $ 20 bill. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . April 20, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016 .

- ↑ SZ, April 22, 2016, p. 17.

- ↑ Mnuchin dismisses question about putting Harriet Tubman on $ 20 bill . In: Politico , August 31, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ↑ Politico: Mnuchin dismisses question about putting Harriet Tubman on $ 20 bill , August 31, 2017

- ↑ Alan Rappeport: Harriet Tubman $ 20 Bill Is Delayed Until Trump Leaves Office, Mnuchin Says. In: The New York Times, May 22, 2019.

- ↑ Alan Rappeport: Biden's Treasury will seek to put Harriet Tubman on the $ 20 bill on the effort Trump administration halted. In: The New York Times . January 25, 2021, ISSN 0362-4331 ( nytimes.com [accessed January 25, 2021]).

- ^ Tubman, Harriet Ross , short biography on the Episcopal Church website

- ↑ March 10 in the ecumenical dictionary of saints

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tubman, Harriet |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ross, Araminta (maiden name); Moses (code name) |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Escape helper for the Underground Railroad |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1820 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dorchester County , Maryland |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 10, 1913 |

| Place of death | Auburn , New York |