Iranian-Portuguese relations

|

|

|

|

|

| Portugal | Iran |

The Iranian-Portuguese relations describe the intergovernmental relationship between Iran and Portugal . The countries have had direct diplomatic relations since 1956.

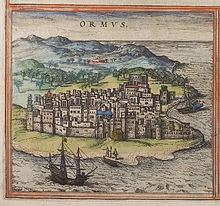

The historical relations between Persia and Portugal, which have existed since the early 16th century, have traditionally been good. Historically, the paths of the two countries crossed for the first time in the 16th century, with the arrival of Portuguese seafarers on the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf . The successful capture of the Persian island of Hormuz in 1507 and with it the control of the Gulfs of Persia and Oman was a decisive key to the continued success of the Portuguese Indian trade, alongside the conquest of Malacca . Some mutual loanwords and everyday terms also have their origins in this time of intensive contact, such as the PortugueseQiosque (from the Persian Kūšk کوشک, German kiosk) or the Persian word for oranges, Porteghal (پرتقال), which is derived from Portugal.

Today both sides are striving to intensify bilateral relations, especially in economic terms, but also culturally and scientifically.

After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, many Iranians fled abroad, some to Portugal. The Portuguese-Iranian rock musician Mazgani is one of them.

In 2015, 546 Iranian citizens were registered in Portugal, with 182 most of them in the Lisbon district . In 2011, 26 Portuguese were registered in the Portuguese consulate in Iran.

history

To 1900

The year 1507 can be regarded as the first official international contact, when an agent of Shah Ismail I wanted to collect the due tribute in Hormuz and met Afonso de Albuquerque there , who had taken the city.

Albuquerque remained Portugal's most important admiral in the Persian Gulf during this period. He also had a fortress built in Hormuz, which was completed around 1515. Albuquerque, the second viceroy of Portuguese India , was pursuing a parallel realignment and organization of its territories, which also included a number of diplomatic missions, including to the court of Ismail I. The Portuguese ambassador was well received at the Persian court and returned with them a Persian official returned to Hormuz, with an opulent gift for the Portuguese viceroy, who received it in a "grand ceremony" in the not-yet-finished fortress.

From 1507 Albuquerque subjugated a number of other cities on the coasts of the Persian Gulf, which from then on were tributary to the Portuguese crown. Hormuz, with its strategically important location at the entrance to the Gulf, remained the military base and commercial center of the Portuguese presence in the region. However, the island did not offer enough water and food and therefore had to be supplied from other Portuguese-controlled bases. The much larger island of Qeschm and its neighbor Larak played an important role in the defense and supply system , but also the fortresses on the mainland, especially those of Comorão (today Bandar Abbas ).

In May 1621, Rui Freire de Andrade , "General of the Sea of Hormuz and the Persian and Arabian Coasts" ( General do Mar de Ormuz e Costa da Pérsia e Arábia ) renewed the fortress of Qeschm to ensure the military security and logistical supply of the island Hormuz continued to guarantee. However, the Shah viewed this construction project as a hostile act.

Portugal, now ruled in personal union with Spain, was experiencing a decline in its colonial empire and found it increasingly difficult to repel attacks, especially against the aspiring British who were in conflict with Spain. The Portuguese and English met for the first time militarily from the naval battle at Dschask in December 1620 / January 1621. On February 11, 1622, Anglo-Persian forces forced the abandonment of the Portuguese fort of Qeschm. On the following February 20, over 3,000 Persian soldiers and six British warships pressed Hormuz for the first time.

On May 12, 1622, Portugal finally gave up the island of Hormuz. The approximately 2,000 Portuguese moved to Muscat , and Hormuz came back into Persian possession, but under British protectorate administration. Various Portuguese attempts at reconquest followed in 1623, 1624, 1625 and 1627. After a final, this time diplomatic, attempt in 1631, Portugal realigned its presence in the Persian Gulf with a new trading post in Bassorá ( Basra ) on the Shatt al-Arab . In addition, Soar ( Suhar ), which had been lost with Hormus, was regained. Once again, Rui Freire de Andrade was responsible for these recent advances, and he also established a branch in Cassapo ( al-Chasab ).

In 1624/1625 the Portuguese signed a treaty with Persia that granted them a fortified trading post in Bandar-e Kong (today in the administrative district of Bandar Lengeh ). The ruins of the once mighty complex can still be seen today. In 1631 another Portuguese fortress was built on the side of the Musandam peninsula facing Persia . In 1633 Rui Freire de Andrade, the most important Portuguese official in the Gulf of Persia, died. He was buried in the Igreja de Santo Agostinho church in Muscat.

Portuguese trade in the region's own factories continued to flourish. In 1648, however, after a siege of Muscat, the Portuguese were forced to abandon and demolish the fortresses of Qurayyat ( Curiate ), Dibba ( Doba ) and Matrah ( Matara ) until the Omanis finally captured Muscat in 1650. This marked the end of the Portuguese presence in the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman.

The Persian-Portuguese contact then naturally decreased, but still existed, especially at the level of diplomacy and trade. Through diplomatic missions such as that of 1696/1697, both sides discussed common interests and agreed on cooperation. Portuguese warships fought against Muscat together with the Persian military, especially in 1715 and 1718.

The Portuguese request for the return of Hormuz without breaking with Persia could not be realized, as Portuguese documents from the years between 1730 and 1758 show. At the same time, these documents prove the normal relationships that still exist.

Since 1900

On October 15, 1956 , Luís Norton de Matos , Portugal's representative in Turkey, accredited himself as the first ambassador to Iran.

On February 10, 1972, Ambassador Carlos Henrique Ferreira Lemonde Macedo began work in the newly opened Portuguese embassy in Tehran.

Since the end of the sanctions related to the Iranian nuclear program in 2016, both sides have been striving to intensify economic relations in particular. The Portuguese State Secretary Jorge Costa Oliveira visited Iran with a business delegation of Portuguese entrepreneurs in June 2016. He stated that the countries wanted to first expand bilateral trade and then develop mutual investment opportunities. He mentioned the areas of manufacturing and tourism, but also the return to Portuguese imports of Iranian oil.

The Iranian side is also striving for a stronger relationship with Portugal. On the occasion of the accreditation of the new Portuguese ambassador in Tehran, Iranian President Hassan Rohani declared in February 2017 that there were no obstacles whatsoever to a comprehensive intensification of bilateral relations, not only in political and economic terms, but also culturally, scientifically, technologically and academically .

diplomacy

Portugal has had an embassy in the Iranian capital Tehran since 1972 , at number 13 on Rouzbeh Street on the well-known Hedayat Avenue in the Darrous district . Furthermore, there are no Portuguese consulates in Iran. However, a Portuguese-Iranian website has been launched for online inquiries about Portuguese entry visas .

Iran has an embassy in the Portuguese capital, Lisbon, at 49 Rua do Alto do Duque . There are no other Iranian consulates in Portugal.

economy

The Portuguese Chamber of Commerce AICEP has an office at the Portuguese Embassy in Tehran.

In 2016, Portugal exported goods worth EUR 18.04 million to Iran (2015: 19.74 million; 2014: 7.03 million; 2013: 7.40 million; 2012: 13.24 million) ), thereof 41.3% paper and cellulose, 15.9% machines and devices, 9.8% chemical-pharmaceutical products and 9.2% vehicles and vehicle parts.

During the same period, Iran delivered goods worth EUR 33.97 million to Portugal (2015: 26.83 million; 2014: 30.63 million; 2013: 13.13 million; 2012: 7.34 million) ), of which 97.3% metals, 1.9% agricultural products, 0.4% ores and minerals and 0.3% chemical-pharmaceutical products.

This put Iran in 86th place as a buyer and in 73rd place as a supplier for Portuguese foreign trade. In Iranian foreign trade, Portugal ranked 33rd among buyers and 56th among suppliers.

Culture

The Portuguese cultural institute Instituto Camões is not represented in Iran, but the Portuguese Gulbenkian Foundation cooperates to preserve the architectural heritage of Portugal in Iran. The projects of the Portuguese fortresses in former Persia, in particular Qeschm and Larak, should be mentioned .

Films from Iranian cinema are regularly featured in Portuguese film festivals . In 1999 Bahman Ghobadi was awarded at the most important Portuguese short film festival, Curtas Vila do Conde , before winning the 2005 Festróia film festival with turtles can fly . In 1997, Majid had already won Majidi with Pedar there .

The Portuguese-Iranian musician Mazgani became known from the mid-1990s, first in Portugal and then internationally, as a representative of the Americana music style.

Sports

Football is extremely popular in both countries.

- Men

The Iranian national soccer team and the Portuguese selection have played against each other twice so far. They first met on June 14, 1972 at the Taça Independência tournament in Recife, Brazil , after which they played against each other on June 17, 2006 in Frankfurt am Main at the 2006 World Cup , both games ended with a Portuguese victory (as of February 2017).

The Portuguese Carlos Queiroz has been the Iranian national coach since 2011 . It led Iran to the 2014 World Cup to Brazil and thus to the country's fourth World Cup participation, which ended again after the preliminary round.

International soccer teams were invited as part of the pompous 2500th anniversary of the Iranian monarchy in 1971. The traditional Portuguese club Académica de Coimbra was a European surprise team at the time, and the student team accepted the invitation of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi .

- Women

The Iranian women's national team and the Portuguese women's national team have not yet met (as of February 2017).

Web links

- Website of the Portuguese Embassy in Iran ( Portuguese and English)

- Overview of diplomatic relations with Iran at the Portuguese Foreign Ministry (port.)

- Solidariedade com o Irão , pro -government Iranian-Portuguese friendship blog

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Overview of diplomatic relations between Portugal and Iran , diplomatic institute in the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs , accessed on May 4, 2019

- ↑ a b c Fernando Cristóvão (Ed.): Dicionário Temático da Lusofonia. Texto Editores, Lisbon / Luanda / Praia / Maputo 2006 ( ISBN 972-47-2935-4 ), p. 816

- ↑ a b Presidente do Irão quer reforçar laços com Portugal ("Iran's President wants to strengthen relations with Portugal"), article of February 5, 2017 in the Portuguese newspaper Público , accessed on March 19, 2017

- ↑ Sums of the number of Iranians in the official foreigner statistics by district , Portuguese Immigration and Border Authority SEF, accessed on March 28, 2017

- ↑ Website on Iranian-Portuguese migration (Table A.3) at the Portuguese scientific Observatório da Emigração , accessed on March 28, 2017

- ↑ a b Fernando Cristóvão (Ed.): Dicionário Temático da Lusofonia. Texto Editores, Lisbon / Luanda / Praia / Maputo 2006 ( ISBN 972-47-2935-4 ), p. 815

- ↑ List of Portuguese Ambassadors to Iran , Diplomatic Institute of the Portuguese Foreign Ministry, accessed on May 4, 2019

- ↑ Portugal a caminho do Irão com um olho nas empresas e outro no petróleo [“Portugal on the way to Iran with one eye on companies and the other on oil”], article from June 6, 2016 in the Portuguese news portal www.noticiasaominuto .com, accessed March 19, 2017

- ↑ List of Portuguese missions abroad , website of the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accessed on March 19, 2017

- ↑ Visa website www.sefarat.eu ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed March 19, 2017

- ^ Entry by the Iranian embassy in Portugal on www.embaixadas.net, accessed on March 19, 2017

- ↑ Overview of the activities of AICEP in Iran , website of the Portuguese Chamber of Commerce AICEP , accessed on March 19, 2017

- ↑ Bilateral economic relations between Portugal and Iran , Excel file retrieval from the Portuguese Chamber of Commerce AICEP , accessed on March 19, 2017

- ↑ Fernando Cristóvão (Ed.): Dicionário Temático da Lusofonia. Texto Editores, Lisbon / Luanda / Praia / Maputo 2006 ( ISBN 972-47-2935-4 ), p. 817