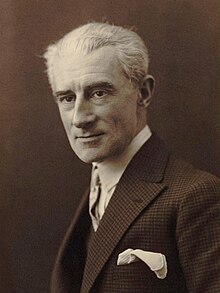

Maurice Ravel

Joseph-Maurice Ravel (born March 7, 1875 in Ciboure , † December 28, 1937 in Paris ) was a French composer and, alongside Claude Debussy, the main representative of Impressionism in music. His best-known work is the orchestral piece Boléro, originally conceived as ballet music .

Life

origin

Joseph-Maurice Ravel was born as the first of two sons in the extreme south-west of France. His father Joseph Ravel (1832-1908) came from Versoix in French-speaking Switzerland and was an engineer by profession . His favorite project, in which he invested a lot of time and money, was the further development of the gas engine . With the Franco-Prussian War between 1870 and 1871, however, his hopes of ever being able to complete the project were dashed. He stayed temporarily in Spain , where he met Marie Delouart, a Baskin . The couple married in 1873 and settled in the French part of the Basque Country near Biarritz . Shortly after Maurice was born, the family moved to Paris in 1875, where the father had found a job. Maurice's brother Edouard, who like his father became an engineer, was born in 1878.

Adolescent years

Ravel received his first piano lessons at the age of seven. The idea of pursuing a career as a musician came early and was supported by my parents. At the age of 13 he received piano lessons and instruction in harmony at a private music school. His teacher Émile Descombes had been a student of Frédéric Chopin . In 1888 Ravel met his classmate Ricardo Viñes , a young talented pianist from Spain. A deep childhood friendship developed between the two that would last a lifetime.

On November 4, 1889, Ravel and Viñes took the entrance exam at the Paris Conservatory . Of 46 candidates, only 19 were admitted to the piano classes: Viñes entered the advanced class, with Ravel it was enough for the preparatory class. With the award of a lecture at the intermediate examination in 1891, he qualified for the class with Charles-Wilfrid Bériot , in which Viñes was also taught.

For a long time Ravel toyed with the idea of embarking on a career as a pianist. But the prerequisites for this were not optimal for him. Warmth, feeling and temperament were attested to his game, but he did not achieve the bravura of other classmates. That seemed to affect his motivation: Ravel was the proverbial “lazy dog”. His teachers resented it; that only seemed to reinforce his stance. In 1893, 1894 and 1895 he failed the compulsory intermediate exams and had to leave the master class again. His interest in becoming a pianist was finally at zero. In later years he was only supposed to sit down at the piano to make his own compositions heard - and even that only reluctantly.

In January 1897 Ravel returned to the Conservatory and entered the composition class of Gabriel Fauré , in addition he studied counterpoint , fugue and orchestration with André Gedalge (teacher of Jacques Ibert , Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud ). It was also Fauré who gave Ravel access to the glamorous salons of what was then Paris. Ravel and Viñes scoffed at the experiences, but as a now pronounced dandy he was also able to enjoy the evenings there. His blasé, cynical appearances with a pleated shirt and monocle, cultivated in the salon, irritated even his best friend Viñes. When asked which school or tendency he belongs to, Ravel used to answer: "Nobody at all, I'm an anarchist."

Les Apaches and Miroirs

Les Apaches The Apaches were musicians, critics, painters and composers such as Paul Sordes, Maurice Delages, Manuel de Falla, Michel Dimitri Calvocoressi and Ricardo Viñes, who wandered through the nightly Paris around 1900 and, as city Indians, defied conventions. They met frequently and Ravel brought many of his new compositions to an unofficial premiere in their circle. So did the Miroirs , the mirror images, which he completed for piano solo in 1905. The group around Ravel also referred to themselves as Noctuelles, as night owls or moths and an analogy to the first title of Miroirs Noctuelles is obvious. Ravel consequently dedicated his five piano pieces to the Apaches.

- Noctuelles to Léon-Paul Fargue

- Oiseaux tristes to Ricardo Viñes

- Une barque sur l'océan to Paul Sordes

- Alborada del gracioso to Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi

- La vallée des cloches to Maurice Delage

Prix de Rome

First attempts

One of Ravel's greatest disappointments is the fact that he competed five times for the Prix de Rome , but always failed. The Prix de Rome was the highest award for young French composers at the time. In January of each year there was an entrance examination; Those who passed this had to go to a preliminary round in May, in which a four-part fugue and a choral work based on a binding text were required, which had to be completed in six days in a retreat. Only a maximum of six participants were admitted to the final round. The task here was to set a text that was also given to music as a two or three-part cantata . The winner of the Prix de Rome - the first prize was not necessarily awarded - received a four-year scholarship to attend the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Ravel applied for the first time in 1900. In March 1900 he wrote to a friend: “I am currently preparing for the Rome Prize competition and have got to work very seriously. It works pretty easily with the joint now; what worries me a few is the cantata. ”But Ravel was eliminated in the preliminary round; the award went to his friend Florent Schmitt . Ravel summed up resignedly:

“Gedalge thought my orchestration was clever and elegant. And all for a failure all along the line. When Fauré tried to stand up for me, Monsieur Dubois [director of the conservatory] assured him that he had illusions about my musical talent. "

In the same year, participation in another joint competition with zero points failed even more devastatingly. Dubois ruled: "Impossible, because of terrible negligence in the spelling." As a result, Ravel was excluded from Fauré's composition class.

But since non-students were also allowed to apply for the Prix de Rome, Ravel made a new attempt in 1901. This time he made it to the final round, but in the end had to share the second prize with a fellow student. The winner was André Caplet , whom Ravel described as mediocre. He later noted: “Almost the entire auditorium would have given me the award.” This is probably how Camille Saint-Saëns saw it , who wrote to a colleague: “The third prize winner, a certain Ravel, seems to me to have what it takes for a serious career Ravel tried again in 1902 and 1903 - and came away empty-handed.

The scandal

His last participation before reaching the maximum application age went to Ravel in 1905. Although he was considered the favorite for the prize, he was eliminated from the competition in the preliminary round due to many violations of sentence and composition rules. Victor Gallois won the award. Ravel's “case” sparked a heated public discussion, less about the compositions he presented than about the question of how the conservatory and competition operations were actually handled. The scandal described in the press as the "Ravel affair" ultimately led to Dubois' resignation as director of the conservatory. The writer and music critic Romain Rolland wrote on May 26, 1905 to the director of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Paul Léon:

“I have absolutely no interests in this affair. I am not a friend of Ravel. I can even say that I personally have no sympathy for his subtle and refined art. But for the sake of fairness I have to say that Ravel is not only a very promising student, he is already one of the most respected young masters in our school, which does not have many of them. [...] Ravel does not apply for the Rome Prize as a student, but as a composer who has already proven his skills. I admire the composers who dared to judge him. Who will judge them now? "

The young composer

As Rolland's letter shows, Ravel was making a name for himself as a composer, even if many of his works met with highly controversial reception. Measured by the number of works completed, the years from the turn of the century to World War I were his most productive. Up until then he had created almost exclusively piano pieces and songs, but with the orchestral overture Shéhérazade , the F major string quartet, the opera L'Heure espagnole , the Rhapsodie espagnole (which attracted Manuel de Falla's attention) and the one composed on behalf of Dyagilev Ballet music Daphnis et Chloé now also larger musical forms. In 1913 Ravel met Stravinsky , with whom he worked on an arrangement of Mussorgski's unfinished opera Khovanshchina .

The First World War

When the First World War broke out , Ravel was gripped by the general patriotic enthusiasm. His brother Edouard had been drafted, and Ravel, who as a young man had been classified as unfit for service because of his small height, tried to join the military. In 1915 he was assigned to the medical service of the 13th Artillery Regiment as a driver. In Paris a "League for the Defense of French Music" was established: works by German and Austrian composers were to be outlawed and no longer performed. Ravel didn't think so. He stated:

“In my opinion it would even be dangerous for French composers to systematically ignore the production of their foreign colleagues and thus form a kind of national clique. Our tonal art, which is so rich at the moment, would inevitably degenerate and lock itself up in template formulas. I don't care that Monsieur Schönberg, for example, is Austrian. "

loss

In 1916, Ravel fell ill with dysentery (see dysentery , amoebic dysentery , and bacterial dysentery ) and subsequently went on convalescence leave in Paris. During this time, Ravel's mother died on January 5, 1917 at the age of 76, an irreplaceable loss for Ravel. Until then he had always lived with her under one roof. But even her death could not induce him to set up his own domicile. Instead, he moved in with his brother Edouard after the war. But when he got married surprisingly in 1920, it was no longer possible to live with him. In 1921 Ravel finally bought the villa “Le Belvédère” (see Musée Maurice Ravel ) in Montfort-l'Amaury, 50 kilometers from Paris , in which he lived until his death. Ravel remained unmarried and childless all his life.

refusal

On January 15, 1920 Ravel was confronted with the news that he had been nominated for the order of a knight of the Legion of Honor ( Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur ). Ravel didn't want that and said angrily: “What a ridiculous story. Who could have played this trick on me? ”He ironed the unwelcome honor off in his own way, against the advice of his friends: He simply did not pay the nomination fees. So he was automatically removed from the candidate list. The improper behavior, however, sparked an excited public discussion, in which he did not participate. Why he refused the award is not clear. He has not withdrawn from other honors: In October 1928 he gladly accepted an honorary doctorate from Oxford University , the same applies to honorary membership of the International Society for Contemporary Music ISCM ( International Society for New Music ) in 1923. Some consider his refusal to be a belated revenge because of the Rome Prize, which was never awarded to him.

End of life

When exactly the diseases began that overshadowed Ravel's final years is not certain. The cause of his illness has not yet been conclusively clarified. Among other things, a stroke, Pick's disease , another dementia or a brain tumor were suspected . As early as the mid-1920s, he had repeatedly complained of insomnia and persistent, unbearable headaches. Exhaustion, in the face of which the doctors advised him to take a longer break, he covered with an almost hectic activity, which resulted in numerous concert tours through Europe , on which he presented his works as a conductor and pianist. In 1928 he went on a four-month tour of the United States and Canada, which took him to 25 cities. The scope of his compositional work, however, decreased. In 1931 Ravel undertook a major European tour with the pianist Marguerite Long .

A car accident on October 8, 1932, which he survived as a passenger in a taxi in Paris with chest bruises and cuts, marked a turning point for the rest of his life. A lesion of the left cerebral cortex led to speech disorders ( Wernicke aphasia and alexia ), and amusia made him lose the ability to compose. Another argument against dementia is that Ravel was in his right mind until the end and watched his decline as if he were a stranger. Desperate, he said: “I still have so much music in my head. I haven't said anything yet. I still have everything to say. "

On December 17, 1937, Ravel went to the clinic of the famous neurosurgeon Clovis Vincent to investigate the suspicion of a brain tumor through a skull operation. A tumor was not found during the operation on December 19, the brain appeared externally normal except for a depression in the left hemisphere, which was attempted to be treated with a serum injection. Ravel woke up from the anesthetic, asked about his brother, but soon sank into a deep coma from which he never woke again. On the morning of December 28, 1937, his heart stopped beating. On December 30th, his remains were buried next to his parents in the Levallois-Perret cemetery in western Paris.

In his honor, Ravel Peak , a mountain on Alexander I Island in Antarctica , has been named after him since 1961 .

Musical influences and relationships

role models

The composer Emmanuel Chabrier was a great role model for Ravel . In 1893 Ravel and Viñes had the opportunity to play for him. Later, too, Ravel spoke of this encounter with pride and emotion. Chabrier is one of the musicians who strongly influenced Ravel in the early days. Ravel wrote in his autobiographical sketches from 1928:

"My first, unpublished works date from around 1893. [...] The Sérénade grotesque was clearly influenced by Emmanuel Chabrier, while the Ballade de la reine morte d'aimer was influenced by Satie."

This quote also includes the name of the second composer to whom Ravel had unlimited admiration: Erik Satie . Its archaic chord shifts, its sparse style, which stood in diametrical contrast to the overloaded sounds of the highly topical " Wagnérisme ", fascinated him. Ravel writes about him:

“Satie was more of an innovator and a pioneer - if not an extremist - than a composer of immortal masterpieces. He anticipated Impressionism à la Debussy, went through it and was one of the first to move away from it. "

Ravel attributed a great influence on the development of his compositional skills to his counterpoint teacher André Gedalge. He also once stated that he had not written a piece that was not influenced by Edvard Grieg .

Ravel's distance from Wagner's style doesn't mean that Ravel didn't appreciate him. He was carried away by many performances, but they have not influenced his work.

Claude Debussy

Distant friendship

It is not known exactly when Ravel met Claude Debussy . It should have been around 1901. Ravel had a great deal of admiration for the works of Debussy, who was 13 years his senior, who, conversely, showed no particular interest in the work of his colleague. Both had regular, albeit distant, polite contact, and Debussy benevolently implored him not to change any note on a new Ravel string quartet, which Fauré had thought he should urgently revise.

The break between the two was initiated by the powerful music critic Pierre Lalo , who first hinted on January 30, 1906 and subsequently in other reviews that Ravel was doing nothing but copying Debussy. He did not make any direct assertion, but so often put the name Ravel in a particular context that no other conclusion could be drawn. Finally, Ravel was prompted to reply, which the editor of Les Temps also reprinted, but in the same issue of the newspaper another derisive article by Lalo appeared under the heading "Monsieur Ravel defends himself without being attacked". In the following years, Ravel and Debussy dropped their contact, obviously without a personal discussion. Both of them later expressed their regrets independently of each other.

When his friend Manuel Rosenthal jokingly asked in 1937 what music he would like for his funeral, Ravel called Debussy's Prelude à l'après-midi d'un faune , because, according to Ravel: “(...) it is the only score that has ever been written that is absolutely perfect. "

Duplicity of events

There are some striking similarities between Debussy and Ravel in the choice of subject. Both Ravel and Debussy set three poems to music under the same title Trois Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé , two of which ("Soupir" and "Placet futile") appeared in both works. Since Ravel had obtained permission to set music from the poet's heirs in advance, he held the copyright to a musical arrangement of the texts. Debussy complained in a letter to a friend dated August 8, 1913:

“The story with the Mallarmé family and Ravel is anything but funny. And isn't it also strange that Ravel chose the same poems as me? Is this an auto-suggestion phenomenon that would be worth reporting to the medical academy? "

Ravel finally intervened in writing in favor of Debussy with the publisher, which Debussy had rejected.

Regardless of the same themes, the search for musical plagiarism would be pointless - Debussy and Ravel composed very individually. Even if some works (Ravel's piano piece Jeux d'eau serve as an example ![]() ) have certain "typically impressionistic" similarities in the use of extended and excessive triads, the use of church modes and bitonality , Ravel's compositions differ from those of Debussy, for example through the more frequent use of more closed forms, dance forms ( bolero , waltz , habanera , malagueña ) and the reference to historical musical models. Ravel's melodic lines sometimes seem clearer. In addition, relatively clear cadences are found more often than with Debussy. His music often seems lighter and more transparent than the sound palette of Debussy, in which the individual voices sometimes get lost in the "boundless".

) have certain "typically impressionistic" similarities in the use of extended and excessive triads, the use of church modes and bitonality , Ravel's compositions differ from those of Debussy, for example through the more frequent use of more closed forms, dance forms ( bolero , waltz , habanera , malagueña ) and the reference to historical musical models. Ravel's melodic lines sometimes seem clearer. In addition, relatively clear cadences are found more often than with Debussy. His music often seems lighter and more transparent than the sound palette of Debussy, in which the individual voices sometimes get lost in the "boundless".

Fellow musicians

In his life Ravel got to know a number of musicians who have remained well-known to this day. a. Igor Stravinsky , Arthur Honegger , Béla Bartók and Arnold Schönberg . The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was one of the perhaps less well-known today . Nevertheless, Wittgenstein's fate has brought posterity an extraordinary work: the “Piano Concerto for the Left Hand”.

Wittgenstein had lost his right arm in the First World War, and his career as a pianist seemed sealed. Nevertheless, he decided to continue his pianist career and commissioned piano works for the left hand from numerous composers, including Ravel. However, the work composed especially for him by Ravel led to a break between composer and artist. The “Piano Concerto for the Left Hand” was launched on January 5, 1932 in Vienna with Wittgenstein at the piano. Since Ravel was not present at the premiere, Wittgenstein organized a soirée for him, at which Ravel was able to hear the piece (on two pianos). After the concert, Ravel approached Wittgenstein and said: “But that's not true at all!” In his opinion, the pianist had not performed the piece as he intended (Wittgenstein had used ornaments that were not included in the musical text). The dispute escalated in a subsequent correspondence in which Wittgenstein argued that the interpreters should not be slaves. Ravel replied succinctly: "The performers are slaves!"

Ravel had very few students, including Maurice Delage and Ralph Vaughan Williams .

Theodor W. Adorno , the philosopher, composer and sharp-tongued critic, was completely enthusiastic about Ravel's L'Enfant et les sortilèges . With Ravel you don't have to be ashamed of reading the lyrics. Especially the book of Colette. Judging by the notes and knowing Ravel's character: 'L'Enfant et les sortilèges' must be his masterpiece. Every beat is childlike with him. Regarding the aspect of form in Ravel, Adorno writes: ... he overlooks (Ravel is meant; d. V.) the world of forms in which he himself is banned; sees through them like glass; but don't pierce the panes, but settle in, as refined as a prisoner.

Other influences

Ravel also drew inspiration for his work from musical styles such as jazz (for example in the Blues movement of the G major violin sonata), oriental music and European folk song . Spanish music was of particular importance for Ravel's compositions. During his lifetime, Ravel always emphasized that he was also a Basque and felt connected to his second home. Works that reflect this influence include a. the opera L'Heure espagnole , the Boléro , the Habanera of the Sites auriculaires , the Alborada del gracioso from the Miroirs , the Vocalise-Étude en forme de Habanera , some songs from the Chants populaires , the triptych Don Quichotte à Dulcinée , the unfinished concert piece for piano and orchestra Zaspiak-Bat (the title means “The Seven Are One” in Basque and means the seven Basque regions) and the Rhapsodie espagnole . In its first movement, a four-tone, descending ostinate figure is repeated over and over again, similar to Ravel's famous Boléro . It appears first in the string instruments and later in the horns , clarinets and oboes . The composer Manuel de Falla wrote:

“The Rhapsodie espagnole surprised me with its Spanish character. […] But how should I explain this subtly authentic Hispanism of the composer […]? I quickly found the solution to the riddle: Ravel's Spain was an idealized Spain, as he had got to know through his mother. […] That probably also explains why Ravel has felt drawn to this country since his earliest childhood, of which he had so often dreamed. "

The second movement, Malagueña , introduces a rhythmically emphasized dance theme in the trumpets and strings, which is increasingly intensified, accompanied by timpani and other percussion.

Ravel took the view that composers should be aware of their individual and national characteristics and criticized American composers for imitating the European tradition instead of recognizing jazz and blues as their own musical tradition. When George Gershwin regretted not having been his pupil, Ravel replied: “Why should you be a second class Ravel when you can be a first class Gershwin?” Influences of Gershwin's style can be seen in Ravel's two piano concertos.

Musical creation

Working method and style

Ravel worked out his compositions with the greatest care and attention to detail and therefore often took a long time to complete, although he wished he could be as fruitful as the great composers he admired. Igor Stravinsky once called him the “Swiss watchmaker” among composers because of the complexity and accuracy of his works. The early printed editions of his works were far more in error than his meticulously worked manuscripts, and Ravel worked tirelessly with his publisher Durand to improve them. During the correction of L'enfant et les sortilèges - he wrote in a letter - after numerous proofreaders had already looked through the work, he still found ten errors on each page.

In Ravel's music, the art of harmony and subtle timbres is praised above all. Ravel saw himself in some respects as a classicist who liked to embed his novel rhythms and harmonies in traditional forms and structures, often blurring the structural boundaries through imperceptible transitions. In the Pavane pour une Infante défunte modern harmonies from Sept- and Septnonakkorden and the "shimmering" impressionistic orchestral will color the work for long stretches by a catchy, in a clear periodicity taken articulated melody part of radicalism. The above-mentioned “blurring of structural boundaries” can be observed in the second two-stroke engine, which has been extended by an eighth . Ravel himself commented on this topic as follows: "What does not deviate slightly from the form lacks the stimulus for feeling - it follows that the irregularity, that is, the unexpected, surprising, striking makes up an essential and characteristic part of beauty."

Further examples of this are his Valses nobles et sentimentales (inspired by Schubert's Valses nobles and Valses sentimentales ), the eight movements of which follow one another without a break, his chamber music, in which many movements have the form of a sonata main movement without a clear distinction between development and recapitulation, and that minuet from the style to the French clavecinists ajar piano suite Le Tombeau de Couperin . Impressionist influences are here through the use of major seventh chords (second quarter of measure 1), minor seventh chords (third quarter of measure 2), seemingly functionlessly ranked minor chords (B minor, A minor, D minor, B minor, F sharp minor in bars 9 to 12) as well as the temporary suspension of the striding movement typical of a minuet (bar 3, bars 9 to 11).

As an orchestrator, Ravel carefully studied the possibilities of each individual instrument. His orchestrations of his own and other piano works, such as Mussorgski's Pictures at an Exhibition , are captivating with their brilliance and richness of color.

Works

Chamber music

Of Ravel's chamber music , the string quartet in F major can be heard most often these days. The work met with vehement resistance when it was first performed in 1904, as a result of which Ravel was excluded from the competition for the Rome Prize. The work impresses with its clear structural structure and the consistent thematic implementation . The two themes of the 1st movement ( audio sample ) are taken up again in the 3rd movement ( audio sample ) and 4th movement in a varied manner and combined with one another. The musicologist Armand Machabey said of the work:

“What is impressive about this work is not the originality of the form, but the perfect execution: there is no banality, there is no idling; rather, there is imagination and a wealth of ideas everywhere, perfect balance of proportions and such a pure and transparent tonal quality that Ravel only achieved in his piano work Jeux d'eau . "

The 1922 sonata for violin and violoncello , which he dedicated to Claude Debussy , shows a harmoniously daring Ravel, the piece has bitonal elements and developing variations. In the second movement of the sonata for violin and piano from 1923 to 1927 (a blues ), the influence of jazz, which was then in vogue in Europe, can be felt. Ravel said on his visit to the USA in 1928:

“I have adopted this popular form of your music. But I dare say that the music I wrote is French anyway, music by Ravel. These popular forms are in reality only building materials, and the work of art proves itself only through the mature conception in which no detail is left to chance. In addition, meticulous stylization in the processing of this material is essential. "

Piano music

Ravel's piano work combines a wide variety of elements: tone painting-impressionistic representations; from the quietly dreamy, such as the reproduction of church bells in La vallée des cloches from the Miroirs and Le Gibet from the Gaspard de la nuit or the depiction of birdsong in Oiseaux dreary to the comical-bizarre or threatening; modern statements in classic forms, for example in the Sonatina or in Le tombeau de Couperin .

Another important element is Ravel's sometimes almost hard motor skills , reminiscent of Stravinsky , as well as the rhythmic power of dance, which we encounter in pieces such as Alborada del gracioso from the Miroirs .

In addition, there is pianistic virtuosity at the highest technical level, as in the Alborada del gracioso from the Miroirs and Ondine or Scarbo ( audio sample ) from the Gaspard de la nuit . Ravel himself made a statement in which he describes overcoming technical difficulties as an artistic act.

The Miroirs and Gaspard de la nuit can be regarded as the two most important piano works of Ravel .

Recordings for Welte-Mignon, Ampico, Duo-Art

In 1912 Ravel recorded two of his own compositions on piano rolls for the Freiburg company M. Welte & Sons , manufacturer of the Welte-Mignon reproduction piano :

- Sonatines No. 1 and 2

- Valses nobles et sentimentales No. 1-8

Further recordings of his own compositions on piano rolls were made between 1923 and 1928 a. a. produced by the American company Ampico ( American Piano Company ) and Duo-Art:

- Toccata from Tombeau de Couperin ( date of manufacture of the piano roll: 1923)

- Oiseaux Tristes from Miroirs No. 2 ( date of manufacture of the piano roll: 1923)

- Pavane for a deceased princess (date of manufacture of the piano roll: 1923)

- Gallows from Gaspard de la Nuit ( date of manufacture of the piano roll: 1925)

- Valley of the Bells from Miroirs No. 5 (date of manufacture of the piano roll: 1928)

Response from the contemporary audience

The contemporary audience reacted very differently to Ravel's works. The audience, who attended concerts not as experts but as music lovers, preferred conservative, harmoniously pleasing works and were often overwhelmed by the unusual harmonies and rhythmic changes in Ravel's compositions. The response to new productions was correspondingly. The situation was different with some of the knowledgeable critics, who expressed sympathy for some of Ravel's new ideas.

- Histoires naturelles

The first performance of the Histoires naturelles , a work for voice and piano, took place on January 12, 1907. The musical performance as well as the articulation of the lyrics were so unusual that the audience let the performers drown in boos and whistles. But an expected hostility from Pierre Lalo in Les Temps was promptly followed by reviews that praised the work in the highest tones. Ravel, on the other hand, saw himself abandoned by the Société Nationale de Musique, which was once founded by Saint-Saëns and had actually taken up the cause of promoting French music. He therefore participated in 1910 in the counter-founding of the Société Musicale Indépendante.

- Rapsodie espagnole

On March 15, 1908, the Rapsodie espagnole was performed for the first time as part of the “Concerts Colonne” directed by Edouard Colonne. In view of the music title, the subscription audience had expected a performance in the style of Saint-Saëns' Havannaise or Rimski-Korsakow's Capriccio espagnol with pseudo- folkloric , snappy effects and were disappointed. Restlessness arose, whistles sounded after the Malagueña, then the ranked Florent Schmitt shouted : "Once again for those down there who have understood nothing." Indeed, Colonne repeated the sentence again, and the rest of the audience finally became more benevolent recorded.

- L'Heure espagnole

The one-act play L'Heure espagnole premiered on May 19, 1911 and was rejected by the audience. The music critics spoke of "musical pornography", Lalo went one better and explained that the "mechanical coldness" of Ravel is characteristic of all of his works.

- Daphnis et Chloé

Ravel began the conception of the ballet Daphnis et Chloé in 1909 on behalf of Sergei Djagilew , the impresario of Ballets russes , for whom Ravel then also reworked his piano duet Ma Mère l'Oye as ballet music. As with many of his works, work on it did not seem to want to go ahead. It premiered on June 8, 1912 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris and was declared a failure.

- Bolero

The best known and most frequently performed work of Ravel is the Boléro . When it was premiered on November 22nd, 1928 as a ballet with the dancer Ida Rubinstein , who initiated the play, it was met with thunderous applause. The world fame of the work was, however, Ravel all his life suspect; he described it as a “simple orchestration exercise” and otherwise commented distantly and almost disparagingly: “My masterpiece? The Boléro, of course. It's just a shame that it doesn't contain any music at all. "

Selection of works

The following selection of the most important works by Ravel is based on the complete chronological catalog of works compiled by Maurice Marnat (see web links):

Piano music

- Habanera for two pianos (1895)

- La parade (1896)

- Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899; orchestral version 1910)

- Jeux d'eau (1901)

- Sonatine pour piano (1903-1905); Sentences: Modéré; Mouvement de menuet; Animé

- Miroirs (1904-1905); Sentences: Noctuelles; Oiseaux dreary; Une barque sur l'océan (orchestral version 1906); Alborada del gracioso (orchestral version 1918); La vallée des cloches

- Gaspard de la nuit after Aloysius Bertrand (1908), movements: Ondine; Le gibet; Scarbo

- Ma mère l'oye , pieces for piano four hands based on fables by Perrault and Mme. D'Aulnoy (1908–1910); Movements: Pavane de la belle au bois dormant; Petit poucet; Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes; Les entretiens de la belle et de la bête; Le jardin féerique

- Valses nobles et sentimentales (1911; orchestral version 1912)

- Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-1917); Movements: Prelude; Fugue; Forlane; Rigaudon; Menuet; Toccata (orchestral version of the 1st and 3rd - 5th movements 1919)

- Frontispice for two pianos for five hands (1918)

Chamber music

- Violin Sonata No. 1 (1897)

- String Quartet in F major (1902–1903); Movements: Allegro moderato; Assez vif, très rythmé; Très lent; Vif et agité

- Introduction and Allegro for harp, flute, clarinet, two violins, viola and cello (1905)

- Piano trio in A minor (1914), movements: Modéré; Pantoum. Assez vite; Passacaille. Très large; Final. Animé

- Sonata for violin and cello (1920–1922)

- Violin Sonata No. 2 (1923–1927)

Orchestral works

- (see also the orchestral versions of the piano works)

- Shéhérazade , ouverture de féerie for orchestra (1898)

- Rapsodie espagnole (1907); Movements: Prélude à la nuit; Malagueña; Habanera; Feria

- Daphnis et Chloé Orchestral Suite No. 1 (1911); Movements: Nocturne avec choeur a cappella ou orchestration seulement; Interlude; Danse guerrière

- Daphnis et Chloé Orchestral Suite No. 2 (1912); Movements: Lever du jour; Mime; Danse générale

- La Valse , choreographic poem for orchestra (1919–1920)

- Boléro , ballet music (1928; version for piano four hands 1929)

Concerts and concert pieces

- Tzigane , Rhapsody for violin and Luthéal (1924) (also as a version for violin and piano or orchestra)

- Piano Concerto in D major for the left hand (1929–1930)

- Piano Concerto in G major (1929–1931)

Vocal music

- Ballade de la reine morte d'aimer , song with piano accompaniment, text by Roland de Marès (1893)

- Les Bayadères for soprano, mixed choir and orchestra (1900)

- Shéhérazade , song cycle for soprano or tenor and orchestra, texts by Tristan Klingsor (1903); Sentences: Asie; La flûte enchantée; L'indifférent

- Histoires naturelles , song cycle for medium voice and piano based on texts by Jules Renard (1906); Sentences: Le paon; Le grillon; Le cygne; Le martin-pêcheur; La pintade

- Vocalise-étude en forme de habanera , song for low voice and piano (1907)

- Trois poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé , song cycle for voice and piccolo, two flutes, clarinets, bass clarinet, two violins, viola, cello and piano (1913; version for voice and piano 1913); Movements: Soupir; Placet futile; Surgi de la croupe et du bond

- Three songs for mixed choir a cappella, texts by Ravel (1914–1915; version for medium voice and piano 1915); Sentences: Nicolette; Trois beaux oiseaux du paradis; Round blank

- Deux mélodies hébraïques (1914) for voice and piano, movements: Kaddisch and L'énigme éternelle ( Jewish folk song)

- Chansons madécasses , song cycle for soprano, flute, cello and piano based on texts by Evariste-Désiré Parny de Forges (1925–1926); Sentences: Nahandove; Aoua; Il est doux

- Don Quichotte à Dulcinée , song cycle for baritone and orchestra based on texts by Paul Morand (1932–33); Movements: Chanson romanesque; Chanson epique; Chanson à boire

Stage works

- L'Heure espagnole (The Spanish Hour), opera, libretto by Franc-Nohain (1907)

- Daphnis et Chloé , ballet music (1909–1912)

- Ma mère l'oye , ballet for orchestra based on the piano suite of the same name (1911–1912)

- L'enfant et les sortilèges , lyrical fantasy based on texts by Colette with 21 roles for soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor and bass parts, mixed choir, children's choir and orchestra (1919-25)

Edits

- Cinq mélodies populaires grecques (1904)

- Claude Debussy : Trois Nocturnes , version for two pianos (1909)

- Claude Debussy : Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune , version for piano four hands (1910)

- Les Sylphides , orchestral version of piano pieces by Frédéric Chopin (1914) (Prelude, Op. 28/7; Nocturne, Op. 32/2; Valse, Op. 70/1; Mazurka, Op. 33/2, 67/3; Prelude , Op. 28/7; Valse, Op. 64/2; Grande valse brillante, Op. 18)

- Robert Schumann : Carnival op.9 (orchestral version) (1914)

- Orchestra version of the piano cycle Pictures at an Exhibition by Modest Mussorgsky (1922)

literature

- Jean Echenoz : Ravel . Novel. German by Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-8270-0693-6

- Theo Hirsbrunner : Maurice Ravel. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 1989, ISBN 3-89007-143-0 ; 2nd, expanded and revised edition. 2014, ISBN 978-3-89007-253-1 .

- Vladimir Jankélévitch, Willi Reich, Paul Raabe: Maurice Ravel in self-testimonies and photo documents. (= Rowohlt's monographs; 13). Rowohlt, Reinbek 1958 (numerous new editions, most recently 1991), ISBN 3-499-50013-2

- Roger Nichols: Ravel . Yale University Press, New Haven and London around 2011, ISBN 978-0-300-10882-8 ( table of contents )

- Arbie Orenstein : Maurice Ravel. Life and work. Reclam, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-15-010277-4

- Roland-Manuel : Ravel. Potsdam, Academic Publishing Society Athenaion 1951

- Gerd Sannemüller : The piano work of Maurice Ravel. (Attempt of a stylistic foundation) . Dissertation, Kiel 1961

- Michael Stegemann: Maurice Ravel. (= Rowohlt's monographs; 538). Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, ISBN 3-499-50538-X

- Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt : Maurice Ravel. Variations on person and work. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-518-36853-2

- Willy Tappolet: Maurice Ravel. Life and work. Olten 1950

- Stephen Zank: Maurice Ravel. A Guide to Research. Routledge, New York and London 2005, ISBN 0-8153-1618-6 (biography, bibliography and catalog raisonné)

- Peter Kaminsky: Unmasking Ravel: New Perspectives on the Music (Eastman Studies in Music). University of Rochester Press, Rochester 2011, ISBN 978-1-58046-337-9 . (English)

- Jean-François Monnard : New critical edition of the symphonic works by Maurice Ravel , 10 volumes, Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden, 2008 to 2014

Web links

- Literature by and about Maurice Ravel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Maurice Ravel in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Maurice Ravel in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Sheet music and audio files by Maurice Ravel in the International Music Score Library Project

- Maurice Ravel in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Literature on Maurice Ravel in the bibliography of the music literature

- www.kreusch-sheet-music.net - Notes in the public domain by Maurice Ravel

- Marnat catalog of the works of Maurice Ravel (French)

- Biography of Maurice Ravel (English)

- Biographical information with links

- Piano Society - Ravel (free recordings)

- Académie internationale de Musique Maurice Ravel in Saint-Jean-de-Luz

- Maurice Ravel's friends: Les Amis de Maurice Ravel

Individual evidence

- ^ ISCM Honorary Members

- ^ Entry Amusie in the Lexicon of Neuroscience. Spectrum Academic Publishing House, Heidelberg 2000.

- ↑ Roger Nichols: Maurice Ravel in the mirror of his time . M & T Verlag, Zurich / St. Gallen 1990, p. 98 .

- ↑ Stephan Hoffmann: Maurice Ravel "My only lover is music" (4). (PDF) SWR2 Music Lesson, January 11, 2018, accessed on January 17, 2018 .

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno, Ravel (1930), in: Gesammelte Schriften 17, Frankfurt / M. 1982, pp. 60-65

- ↑ 2003 published on audio CD (DSPRCD004) by the label Dal Segno in the series "Masters of the Piano Roll" and under the title "Ravel plays Ravel".

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ravel, Maurice |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ravel, Joseph-Maurice (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 7, 1875 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ciboure |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 28, 1937 |

| Place of death | Paris |