propaganda

Propaganda (from the Latin propagare , `` further spread, spread, spread '') describes in its modern meaning the targeted attempts to form political opinions or public perspectives , to manipulate knowledge and to steer behavior in a direction desired by the propagandist or ruler . Not to explain the different sides of a topic and the mixing of information and opinion characterize the propaganda techniques . This is in contrast to pluralistic and critical perspectives, which are shaped by different experiences, observations and evaluations as well as a rational discourse .

History of meaning

Counter-reformation

The term is derived from the Latin name of a papal authority, which was given by Gregory XV in 1622 . Sacra congregatio de propaganda fide , launched in the course of the Counter-Reformation , in German roughly “Holy Congregation for the Dissemination of Faith”, today officially “Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples.” In the 17th century, the short form propaganda - actually the Gerundive form from Latin propagare , "spread, expand" - as the name for this mission society , whose purpose was to oppose Protestantism and to proselytize the New World .

French Revolution

Since around the time of the French Revolution , the word has been used in today's secular sense, i.e. as a term for the spread of political ideas. In 1790 the Club de la propagande was formed in Paris , a secret society of the Jacobins to spread revolutionary ideas. The term can be found with this meaning in many other languages today.

Scientific foundation

In the 1920s, the scientific investigation of the topic began, whereby the term was understood largely neutral as a fundamental and necessary fact of social life.

Edward L. Bernays , the founder of what he later renamed Public Relations , initially defined it as “a coherent, sustained effort to create or shape events to influence public relations with a company, idea, or group . ”He distinguished the modern propaganda systematically planned and medially conveyed with the help of market research, demoscopy and psychology from older, less professional forms. His psychoanalytic orientation led him to understand the importance of the subconscious and the phenomena of displacement and displacement as the basis of successful propaganda. Instead of direct appeals and rational arguments, his propaganda technique relied on the recipient's unconscious indirect generation of needs, which the recipient experiences as his own wishes and as an expression of his free will. Bernays assumed that democratic participation of the citizens and the legitimation of state action would be best served if the state, with the help of scientific methods and factual analyzes by experts, influences and directs public opinion in such a way that a consensus is created and the government for theirs Politics finds support.

Bernays referred, among other things, to the work of the American political theorist and journalist Walter Lippmann . This saw the creation of a unified opinion ("manufacturing consent") one of the main tasks of the mass media in cooperation with the decision-makers. He saw this as a "specialized class" English specialized class , to which the essential political decisions should be reserved.

In Harold D. Lasswell's understanding of propaganda, the semiotics of symbolic interaction played a decisive role for the first time.

Usage today

As a result of the monopoly of propaganda in dictatorial regimes, particularly under National Socialism and Stalinism , the term acquired a strongly pejorative (derogatory) character and is now almost exclusively used critically. Because of this negative connotation , the term propaganda was replaced early by Edward Bernays himself through public relations (or the English public relations ). Today the term “propaganda” is used primarily critically for political and military influencing of public opinion; in economic terms, one speaks more of “ advertising ” and “public relations” today , in religious terms of “ proselytizing ”, in politics more affirmatively of public diplomacy , in military campaigns of psychological warfare .

As a result of the devaluation of the term used z. For example, none of the democratic parties in the Federal Republic of Germany use the term propaganda for their advertising . The media scientist Norbert Bolz , however, called "empty" campaigns (in the 2013 election campaign), which have nothing to do with political election campaigns but rather with feeling good, as "feeling good propaganda". In 2018, Bolz identified the flood of news in world communication from the new electronic media as the main reason for the citizens' inability to form their own opinion, and thus their susceptibility to “off the shelf opinion”, which he equates with propaganda. But in democratic countries it is by no means about brainwashing and censorship, and there is no corrective to be found in new, internet-based media. The publicist Gero von Randow wrote in 2015: "Propaganda requires organization."

In 1988, Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman published in their work Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media a “ propaganda model of communication”, according to which in Western countries uncontrolled “filtering” of information by the mass media prevents objective reporting. According to Joan Pedro-Carañana , Daniel Broudy and Jeffery Klaehn , it is now considered a valid, internationally empirically proven , scientific model.

Definition and character

Garth S. Jowett and Victoria O'Donnell define propaganda as the deliberate systematic attempt perceptions ( perceptions to shape), the understanding of facts to manipulate and behavior to control, so that a reaction is caused, which promotes the desired goal of the propagandists .

Harold D. Laswell's definition aims even more clearly at the technical aspect:

“Propaganda in the broadest sense is the technique of influencing people's actions by manipulating representations. These representations can be spoken, written, pictorial or musical. "

The manipulation can be controlled or uncontrolled, conscious or unconscious, it can be political or social. The concept of propaganda ranges from the state consciously controlled influencing of public opinion ( Edward Bernays ) to "sociological propaganda", in which individuals manipulate themselves unconsciously and allow themselves to be manipulated in order to meet social expectations ( Jacques Ellul ):

The propagandist dramatizes our prejudices and addresses something deep and even shameful within us. Propaganda thus becomes a co-production in which we willingly collaborate; it expresses what we whisper to ourselves in a low voice. Propaganda is less of a stimulus-response mechanism than a fantasy or a conspiracy in which we are part, the conspiracy of our own self-deception.

The transition from non-propaganda to propaganda is fluid. Effective manipulation requires a non-manipulative embedding in order to be able to develop its effect, which is why the reference to the contexts is not yet a refutation of the manipulative character of an act of communication. Propaganda can only work if it takes into account the situation and needs of the recipient and includes his or her own activity in the process of persuasion.

Propaganda is understood as a form of manipulation of public opinion or of opinions in general, with the semiotic instrumentalization of symbols in the foreground ( "Propaganda is a major form of manipulation by symbols" ).

Propaganda thus belongs to a special form of communication that is examined in communication research , and here especially in media impact research, from the point of view of media manipulation . Propaganda is a certain type of communication that is characterized by the fact that the representation of reality is distorted.

Media that can convey propaganda messages include news, government releases, historical representations, pseudoscientific analysis, books, pamphlets, films, social media, radio, television, and posters. Postcards or envelopes are less common these days.

In the case of radio and television, propaganda can appear on news, news or talk shows, as advertisements or as a public political statement. Propaganda campaigns often follow a strategic plan to indoctrinate the target audience. This can start with a leaflet or a commercial. In general, these messages contain references to further information via a website, a hotline, a radio program, etc. The strategy aims to lead the recipient through reinforcement mechanisms from information intake to information search, and then from information search through indoctrination to active opinion leadership.

Propaganda and International Law

According to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Art. 20), which was ratified by 168 states, war propaganda has been prohibited since 1976.

With regard to political and military conflicts, propaganda is assigned to psychological warfare and information warfare , which are of particular importance in the age of hybrid warfare and cyber warfare .

Historical examples

War propaganda in the First World War

Targeted and organized war propaganda was pursued by all belligerent powers, in the German Empire it was mainly the Supreme Army Command , in Great Britain the War Propaganda Bureau and in France the Maison de la Presse .

For example, so-called wall attacks played an important role in psychological warfare , both with the Central Powers and with the Entente and their allies. Numerous artists participated in Germany, u. a. Walter Trier , Louis Oppenheim and Paul Brockmüller , on the design of numerous posters .

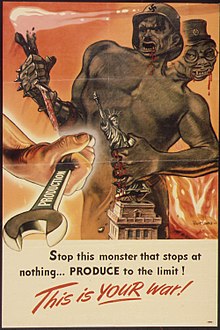

War propaganda in World War II

In the warring countries propaganda was made against the war opponents. The invention of film , in particular , led to a large number of propaganda films .

Nazi propaganda

Adolf Hitler and his Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels gave in the era of National Socialism before the war from 1933 propaganda a totalitarian and dominant importance, benefiting especially the press , the radio , all the media of the arts and symbolically striking reared mass events .

Allied propaganda

The anti-Hitler coalition operation on the United States Office of War Information and the Ministry of Information of the United Kingdom several enemy broadcasts and radio propaganda , and the German Wehrmacht and especially Adolf Hitler was often made ridiculous on posters.

Communist agitation and propaganda (agitprop)

Lenin's understanding of propaganda

Lenin understood propaganda as the general work of convincing communists , in contrast to agitation , which was an “ appeal to the masses to take certain concrete actions ”. Especially in the early days of the Soviet Union , the agitprop was influenced by modern art movements ( futurism ).

Propaganda in the GDR

Agitprop was an important means of securing rule of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) in the German Democratic Republic . Your goal was u. a. in the discrediting of the economic and social order of the Federal Republic of Germany . It was directed against capitalism and "Western imperialism " in general . Since all media were censored and controlled by the state, its propaganda was omnipresent. As permanent political-ideological indoctrination , it was already practiced in state kindergartens and continued in school lessons ( civics ). Mass organizations such as Young Pioneers , FDJ , FDGB and others were an integral part of the state's propaganda apparatus. The penetration of families through propaganda, the suppression of the opposition and the attempted influence on society as a whole are typical characteristics of totalitarian rule .

An important element of the GDR propaganda was the television program The Black Canal . Propaganda methods were an integral part of training for cadres ; B. in the "Red Monastery", the Faculty of Journalism in Leipzig , a training facility that was directly subordinate to the Central Committee of the SED .

The GDR also dealt propagandistically with the emergency laws of the Federal Republic of Germany and established a connection to the National Socialist judiciary .

Propaganda in the Federal Republic of Germany during the Cold War

In the Federal Republic of Germany , propaganda was used during the Cold War in public radio and television broadcasters and private media as well as in many other areas of daily life, often with a strong turn against the GDR. The Federal Ministry for intra-German relations and private-law propaganda organizations such as B. the Volksbund for Peace and Freedom , but also some political parties that stirred up fear with their anti-communist stance and campaigned.

In addition to open propaganda in everyday life, there were also covert state actions that were systematically carried out by the Federal Ministry of Defense as operational information . The then Defense Minister Franz Josef Strauss set up a department for psychological warfare in 1958 , in which u. a. Eberhard Taubert , former employee in the Reich Ministry of Propaganda , played a leading role.

Contemporary examples

Russian government propaganda

Shortly after the Beslan hostage-taking in September 2004, President Putin reinforced a Russian government-sponsored project to improve Russia's image in the world. A major project in 2005 was the creation of the English-language program for Russia Today , which offers a continuous program of the latest news and was modeled on the US broadcaster CNN . CBS News quoted the political scientist Boris Kagarlitsky at the start of the station, saying that Russia Today is largely continuing the old Soviet propaganda.

USA: Pentagon Military Analyst Program 2002–2008

In the wake of the war on terror launched by the George W. Bush administration , the United States Department of Defense launched a propaganda strategy in 2002 to convey the American government's perspective on foreign policy issues such as the Iraq and Afghan wars and the Guantanamo Bay prison camp in to spread to the public. The ministry gave preferential information to selected experts, mostly veterans , and broadcast the government's arguments on radio and television. Fearing that they would lose privileged access, some of them spread this view after suppressing doubts themselves. The program was exposed in 2008 by journalist David Barstow with the help of the Freedom of Information Act , which attracted a lot of public attention.

USA and Great Britain: Establishment of the Iraq War 2003

The governments of the United States and Great Britain have reported since 2001 that Iraqi ruler Saddam Hussein posed an acute international threat because he might still be in possession of weapons of mass destruction, which is why a United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission was established. This threat was cited as the main justification for the " illegal international war of aggression " against Iraq. The Center for Public Integrity found 935 public false statements by government officials in the United States and spoke of a “carefully orchestrated campaign of falsehoods” that had been “methodically propagated”.

Germany: Influencing the reporting of leading media through the connections between journalists and political and business elites

The media scientist Uwe Krüger , who examined the social environment of 219 leading editors of German leading media, assumes that in the Federal Republic of Germany "a consensually united elite governs on important issues (war and peace, macroeconomic order) against the interests of a large part of the population can and that journalistic elites could be too deeply involved in the elite milieu to still act as advocates of the public interest in a critical and controlling manner. "

He found that every third journalist examined had informal contacts with political and business elites. With four foreign policy journalists, Stefan Kornelius , Klaus-Dieter Frankenberger , Michael Stürmer and Josef Joffe, there are dense networks in the US and NATO-affine elite milieu.

War reporting by German, British and American leading media

The journalism researcher Florian Zollmann examined differences in the war reporting of major German, British and American newspapers such as u. a. the New York Times, the Guardian and the Süddeutsche Zeitung. He compared 1911 articles on human rights violations that were committed by different warring parties during various acts of war in Kosovo, Iraq, Libya, Syria and Egypt and examined them with regard to the question of whether there were systematic differences in the assessment made and the call for sanctions or humanitarian interventions . The result of his investigation was that human rights abuses committed by "hostile" parties are highlighted more strongly and calls to stop these abuses are more emphatic than when human rights abuses are committed by Western states or their allies.

Linguistic propaganda techniques

Propaganda, persuasion and rhetoric are often used in the same way or in the same context. Scientists have analyzed or developed a variety of propaganda techniques, some of which are also classified as logical fallacies (fallacies) and pseudo-arguments , as rhetorical devices or eristic stratagems .

According to Charles U. Larson, language is used for three types of propaganda: hypnotic, semantic, and cognitive propaganda. The hypnotic one lets the recipient think the desired thought for himself by making him interpret the facts from his point of view through blanks: "We have to defend our values ". The semantic propaganda works with omissions, generalizations and distortions of the linguistic sense, the cognitive leads to cognitive distortion or exploits psychological tendencies of the distortion. Larson sees hypnotic, cognitive and semantic propaganda in close connection.

Serge Moscovici sees linguistic propaganda in a system of rule as the third level of influencing people's ideas. The first level is the room and its atmospheric effect, the second level the type of event, such as a celebration, the word spoken at this location and on this occasion, according to its representation, also contains a persuasive meaning due to the atmosphere and context.

literature

- general

- Jonathan Auerbach, Russ Castronovo (Ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies. January 9, 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-976441-9 .

- Edward Bernays : Propaganda . Horace Liveright, New York 1928. New edition: Ig Publishing, Brooklyn NY 2005, ISBN 0-9703125-9-8 ; German edition translated by Patrick Schnur, orange-press, Freiburg i. Br. 2007, ISBN 978-3-936086-35-5 .

- Thyme Bussemer: Propaganda. Concepts and theories. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-8100-4201-3 .

- Jacques Ellul : Propagande . A. Colin, Paris 1962.

- Stuart Ewen: PR! A Social History of Spin. Basic Books, New York 1996, ISBN 0-465-06168-0 , ISBN 0-465-06179-6 .

- Rainer Gries, Wolfgang Schmale (ed.): Culture of Propaganda. Reflections on a propaganda history as a cultural history. Winkler, Bochum 2005, ISBN 3-89911-028-5 .

- Wolfgang Schieder, Christof Dipper: Propaganda. In: Otto Brunner , Werner Conze , Reinhart Koselleck (eds.): Basic historical concepts. Historical lexicon on political and social language in Germany. Volume 5, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-608-91500-1 , pp. 69-112.

- Ferdinand Tönnies : Critique of Public Opinion. 1922. In: Ferdinand Tönnies complete edition . Volume 14, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2002.

- War propaganda

- Andrej Bartuschka: The other war: US propaganda and counterinsurgency in the Cold War using the example of the Vietnam conflict . Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Trier 2013, ISBN 978-3-86821-451-2 (Dissertation University of Jena 2011, 556 pages).

- Klaus-Jürgen Bremm : Propaganda in the First World War . Theiss, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-8062-2754-3 .

- Ortwin Buchbender, Horst Schuh: The weapon that aims at the soul. Psychological warfare 1939–1945. Motorbuch, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-87943-915-X .

- Martin Jung: Propaganda for War. In: Nigel Young (Ed.): The Oxford international encyclopedia of peace. 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-533468-5 .

- Phillip Knightley : The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Iraq. 3rd edition: 2004, ISBN 0-8018-8030-0 .

- Marcus König: Agitation - Censorship - Propaganda: the submarine war and the German public in World War I Ibidem, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-8382-0632-5 Dissertation University Mainz 2012, 829 pages, under the title: The public discourse on submarine warfare in the First World War .

- Anne Morelli : The Principles of War Propaganda . zu Klampen, Springe 2004, ISBN 978-3-934920-43-9 .

- John Oddo: The Discourse of Propaganda: Case Studies from the Persian Gulf War and the War on Terror. Penn State University, University Park 2018, ISBN 978-0-271-08117-5 .

- Individual states

- Annuß Evelyn: "Elementary school of the theater: National Socialist Mass Games", Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2018. ISBN 978-3-7705-6373-9 .

- Judith Barben: Spin doctors in the Bundeshaus. Threats to direct democracy through manipulation and propaganda. Eikos, Baden (Switzerland) 2009, ISBN 978-3-033-01916-4 .

- Peter Bürger: Cinema of Fear. Terror, war and statecraft from Hollywood. Butterfly, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-89657-471-X .

- Gerald Diesener, Rainer Gries (ed.): Propaganda in Germany. On the history of political mass influence in the 20th century. Primus, Darmstadt 1996, ISBN 3-89678-014-X .

- Dimitri Kitsikis , Propagande et pressions en politique internationale , Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1963, 537 pages.

- Klaus Körner : The red danger. Anti-communist propaganda in the Federal Republic of 1950–2000. Konkret, 2002, ISBN 3-89458-215-4 .

- Johann Plenge : German Propaganda. The doctrine of propaganda as practical social theory , afterword by Ludwig Roselius , Angelsaches-Verlag, Bremen 1922, DNB 575396539 ²1965.

- Christian Saehrendt : Art as an ambassador for an artificial nation. Studies on the role of the fine arts in the foreign cultural policy of the GDR. Steiner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-515-09227-2 .

- Harro Segeberg (Ed.): Medial mobilization. The Third Reich and the Film. Fink, Paderborn 2004, ISBN 3-7705-3863-3 .

Movies

- Children, cadres, commanders - 40 years of GDR propaganda - documentary, 90 min. A compilation film that retells the history of the GDR using its own propaganda films (German and English). Trailer .

See also

- Agitprop

- 50 cent party

- Hasbara

- Propaganda (Bernays)

- Troll army

- Coin minting as a means of propaganda, e.g. truth thaler and mosquito thaler

State and private forms of propaganda

20th century people

- Ilja Ehrenburg - Soviet propagandist and war correspondent in World War II

- Leni Riefenstahl - German director of several National Socialist propaganda films

- Joseph Goebbels - Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda

Others

Web links

- Literature on propaganda in the catalog of the German National Library

- Christian Schwendinger: What is propaganda? In: Rheton. Online journal of rhetoric. April 10, 2007.

- Thymian Bussemer: Propaganda , Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia Contemporary History , August 2, 2013

- Pedro-Carañana; Broudy; Klaehn: The Propaganda Model Today, http://www.oapen.org/search?identifier=1002463

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Thymian Bussemer: Propaganda: Concepts and Theories . Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-16160-0 , pp. 26th f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ So Norstedt u. a .: From the persian Gulf to Kosovo - War Journalism and Propaganda. In: European Journal of Communication. 15, 2000, pp. 383-404.

- ↑ a b Federal Agency for Civic Education: What is Propaganda? Accessed on February 24, 2017 : “Propaganda is the attempt to specifically influence the way people think, act and feel [...] It is characteristic of propaganda that it does not explain the different sides of a topic and mixes opinion and information. [...] Propaganda relieves people of thinking and instead gives them the feeling that they are right with their adopted opinion. "

- ^ Gerhard Maletzke: Propaganda. A conceptually critical analysis. In: Journalism. 17, Issue 2, 1972, pp. 153–164, definition p. 157: "'Propaganda' should mean planned attempts to influence the opinion, attitudes and behavior of target groups with political objectives through communication."

- ↑ Kristoff M. Ritlewski: Pluralism as a structural principle in broadcasting: requirements from the functional mandate and regulations for security in Germany and Poland . Peter Lang, 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-59406-3 , pp. 3 ( books.google.de [accessed on February 24, 2017]).

- ^ Thomas Morawski, Martin Weiss: training book television reportage. Reporter's happiness and how to do it - rules, tips and tricks. With special section war and crisis reports . Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-90701-7 , pp. 303 ( google.de [accessed on February 24, 2017]).

- ↑ Christer Petersen: Terror and Propaganda: Prolegomena to an Analytical Media Studies . transcript Verlag, 2017, ISBN 978-3-8394-2243-4 ( books.google.de [accessed on February 24, 2017]).

- ^ Duisburg Institute for Linguistic and Social Research - Text and Discourse Analysis. Retrieved February 24, 2017 .

- ^ Propaganda. In: Digital dictionary of the German language .

- ^ Scott M. Cutlip: The Unseen Power: Public Relations: A History . Routledge, 2013, ISBN 978-1-136-69000-6 ( books.google.de [accessed February 24, 2017]).

- ^ A b Thymian Bussemer: Propaganda: Concepts and Theories . Springer, 2015, ISBN 978-3-663-11182-5 ( books.google.de [accessed February 24, 2017]).

- ^ Edward Bernays: Propaganda , ICH - Information Clearing House (first published in 1928), August 20, 2010, accessed on February 24, 2017.

- ^ The Rise of the All-Consuming Self and the Influence of the Freud Dynasty - from Sigmund to Matthew. In: BBC - Press Office. February 28, 2002, accessed February 24, 2017 .

- ^ Edward L. Bernays: The Engineering of Consent . In: The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science . tape 250 , no. 1 , March 1947, ISSN 0002-7162 , p. 113-120 , doi : 10.1177 / 000271624725000116 .

- ^ Walter Lippmann: Public opinion . New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1922, pp. 248 f., 309 ff . ( archive.org ).

- ^ Jeffery Klaehn: A Critical Review and Assessment of Herman and Chomsky's 'PropagandaModel' . In: European Journal of Communication . tape 17 , no. 2 , June 2002, ISSN 0267-3231 , p. 147-182 , doi : 10.1177 / 0267323102017002691 .

- ^ Stanley Baran, Dennis Davis: Mass Communication Theory: Foundations, Ferment, and Future . Cengage Learning, 2008, ISBN 0-495-50363-0 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Lexikon der Politik , Vol. 7, ISBN 3-406-36911-1 , p. 524.

- ^ Kathrin Mok: Political Communication Today: Contributions of the 5th Düsseldorf Forum Political Communication . Frank & Timme GmbH, 2010, ISBN 978-3-86596-271-3 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Military Psychological Operations Manual. Mind Control Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-0-557-05256-1 .

- ^ Gerhard Strauss, Ulrike Haß-Zumkehr, Gisela Harras: explosive words from agitation to zeitgeist. de Gruyter, Berlin, 1989, p. 304.

- ↑ Party advertising as "feel-good propaganda". Retrieved December 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Norbert Bolz: The thoughts are not free , NZZ Folio The Opinion , Folio 6/2018, p. 27.

- ↑ Gero von Randow: We are surrounded. In: The time . July 24, 2015.

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam: Manufacturing consent. The political economy of the mass media . Updated ed. New York 2002, ISBN 0-375-71449-9 .

- ↑ Joan Pedro Carañana, Daniel Broudy, Jeffery Klaehn: Introduction . In: The Propaganda Model Today: Filtering Perception and Awareness . University of Westminster Press, 2018, ISBN 978-1-912656-16-5 , pp. 1-18 , doi : 10.16997 / book27.a .

- ↑ Joan Pedro Carañana, Daniel Broudy, Jeffery Klaehn: The propaganda model today: filtering perception and awareness . London 2018, ISBN 978-1-912656-17-2 , pp. 2 .

- ^ Garth Jowett, Victoria O'Donnell: Propaganda and Persuasion . SAGE, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4129-0898-6 ( com.ph [accessed June 30, 2019]): “Propaganda is the deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist. "

- ^ Lasswell, Harold Dwight (1937): Propaganda Technique in the World War. ISBN 0-262-62018-9 , pp. 214-222. "Propaganda in the broadest sense is the technique of influencing human action by the manipulation of representations. These representations may take spoken, written, pictorial or musical form. "

- ^ Stanley B. Cunningham: The Idea of Propaganda: A Reconstruction . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 978-0-275-97445-9 ( com.ph [accessed July 3, 2019]).

- ^ Thyme Bussemer: Propaganda: Concepts and Theories . Springer-Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-16160-0 ( com.ph [accessed July 2, 2019]).

- ↑ Nicholas J. O'Shaughnessy: Politics and Propaganda: Weapons of Mass Seduction . Manchester University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-7190-6853-9 ( google.de [accessed July 7, 2019]).

- ^ Stanley B. Cunningham: The Idea of Propaganda: A Reconstruction . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 978-0-275-97445-9 ( com.ph [accessed July 3, 2019]).

- ↑ Bussemer Thymian: Psychology of Propaganda | APuZ. Retrieved on July 7, 2019 : "..... Propaganda is only half the agent of the groups operating it. In the other half it becomes an expression of the needs of the recipient. It is therefore a medium in which interests are negotiated and it can only be successful if it represents authentic interests "from below". This reciprocity - the anticipation of existing interests by propagandists and the acceptance and dissemination of the propaganda messages tailored to them by the recipients - is, according to today's understanding, the actual core of propaganda communication. "

- ^ John Scott: Power: Critical Concepts . Psychology Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-415-07938-9 ( com.ph [accessed June 30, 2019]).

- ↑ Paul M. Haridakis, Barbara S. Hugenberg, Stanley T. Wearden: War and the Media: Essays on News Reporting, Propaganda and Popular Culture . McFarland, 2014, ISBN 978-0-7864-5460-0 ( com.ph [accessed June 30, 2019]).

- ^ Thyme Bussemer: Propaganda: Concepts and Theories . Springer-Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-16160-0 ( com.ph [accessed July 2, 2019]).

- ↑ Robert Cole, ed. Encyclopedia of Propaganda (3 vol 1998)

- ↑ International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of December 19, 1966. Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany .

- ↑ Ramesh Bhan: Information War: (Dis) information will Decide Future Wars . Educreation Publishing, December 26, 2017 ( com.ph [accessed June 30, 2019]).

- ↑ Florian Schaurer, Hans-Joachim Ruff-Stahl: Hybrid threats. Security policy in the gray area | APuZ. Retrieved July 1, 2019 .

- ↑ in detail Ferdinand Tönnies , Critique of Public Opinion. 1922.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw: The Eternal Question "Why?" , SRF, June 3, 2012, minute 23:50

- ^ Federal Agency for Civic Education : History of War Propaganda

- ↑ Lenin , What to do? Burning Questions Our Movement , 1902, esp. Chapter 3b: The Story of How Martynov Deepened Plekhanov.

- ^ Günther Heydemann , Die Innenpolitik der DDR , in: Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte , Volume 66, Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-55770-X , p. 99 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Henning Schluß (Ed.): Indoctrination as a code in the SED dictatorship - indoctrination and education. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007, ISBN 978-3-531-15169-4 , pp. 35–47.

- ^ Monika Gibas : Propaganda in the GDR. Erfurt 2000.

- ↑ Gerald Diesener, Rainer Gries (Ed.): Propaganda in Germany. On the history of political mass influence in the 20th century. Darmstadt 1996.

- ↑ Günther Heydemann, History Image and History Propaganda in the Honecker Era. In: Ute Daniel, Wolfram Siemann (ed.): Propaganda. Opinion conflict, seduction and political creation of meaning 1789–1989. Frankfurt a. M. 1994, pp. 161-171.

- ↑ Brigitte Klump, The Red Monastery. As pupils in the Stasi cadre school. Ullstein Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1993, ISBN 3-548-34990-0 .

- ↑ Federal Archives, B141 / 155531; see. 76th meeting on May 16, 1963

- ↑ Monika Gibas, Dirk Schindelbeck (ed.): "The homeland has made itself beautiful ..." - 1959: Case studies on the German-German propaganda history. Leipzig 1994.

- ↑ Gerald Diesener, Rainer Gries (Ed.): Propaganda in Germany - On the history of political influence on the masses in the 20th century , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1996, pp. 113 ff., 235 ff.

- ↑ Klaus Körner: "The Red Danger". Anti-Communist Propaganda in the Federal Republic 1950–2000 , Konkret Literatur Verlag, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-89458-215-4 , pp. 30 ff., 21 ff., 50 ff.

- ↑ Dirk Drews: The psychological warfare / psychological defense of the Bundeswehr. An educational and journalistic study. (PDF; 3.4 MB) (No longer available online.) 2006, archived from the original on January 22, 2017 ; Retrieved on July 28, 2018 (Inaugural dissertation to obtain the academic degree of Dr. phil., presented to Faculty 02: Social Sciences, Media and Sport at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz).

- ↑ Peter Finn: Russia Pumps Tens of Millions Into Burnishing Image Abroad. In: The Washington Post . March 6, 2008 (English).

- ↑ «Честь России стоит дорого». Мы выяснили, сколько конкретно. In: Novaja Gazeta , July 21, 2005 (Russian); Имидж за $ 30 млн. In: Vedomosti . June 6, 2005 (Russian).

- ^ Journalism mixes with spin on Russia Today: Critics. ( Memento from June 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) In: CBC News . March 10, 2006 (English).

- ^ David Barstow: Behind TV Analysts, Pentagon's Hidden Hand. In: The New York Times . April 20, 2008

- ^ David Sessions: Onward, TV Soldiers. In: Slate . April 20, 2008 (English).

- ^ Garth S. Jowett, Victoria O'Donnell: Propaganda & Persuasion . 6th edition. SAGE Publications, 2014, ISBN 978-1-4833-2352-7 , pp. 382 ff .

- ↑ Fernando R. Tesón: Appendix The Iraq War . In: Oxford Scholarship Online . October 19, 2017, doi : 10.1093 / oso / 9780190202903.003.0007 .

- ↑ a b Krüger, Uwe, 1978–: Power of Opinion The Influence of Elites on Leading Media and Alpha Journalists - A Critical Network Analysis . Herbert von Halem Verlag, 2014, ISBN 978-3-86962-124-1 .

- ↑ a b Zollman, Florian, 1976-: Media, propaganda and the politics of intervention . New York, ISBN 978-1-4331-2823-3 .

- ↑ Oliver Boyd-Barrett: Book review: Media, Propaganda and the Politics of Intervention . In: Cooperation and Conflict . tape 53 , no. 2 , June 2018, ISSN 0010-8367 , p. 296-298 , doi : 10.1177 / 0010836718768640 .

- ^ Tabe Bergman: Media, Propaganda and the Politics of Intervention . In: European Journal of Communication . tape 33 , no. 2 , April 2018, ISSN 0267-3231 , p. 242-244 , doi : 10.1177 / 0267323118761156 .

- ↑ Persuasion and Propaganda. (PDF) p. 1 , accessed on March 14, 2017 .

- ↑ Robert Cole, ed. Encyclopedia of Propaganda (3 vol 1998)

- ↑ Psychological Operations Field Manual No. 33-1 . Headquarters; Department of the Army, Washington DC 1979.

- ^ Charles U. Larson: Persuasion: Reception and Responsibility . Cengage Learning, 2009, ISBN 0-495-56750-7 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Anxiety Culture: The Propaganda System. Retrieved March 14, 2017 .

- ^ Ivana Marková: Persuasion and Propaganda. (PDF) p. 41 , accessed on March 14, 2017 .