Cowhide

As cattle hide , the hairy skins of various domestic cattle - and wild cattle breeds , as calfskin is the hairy skins of young animals. As a by-product of the meat industry , they are a commodity in the tobacco trade . The skin trade also differentiates between tame and wild skin . Tame skins are the skins of European domestic cattle that are obtained from slaughter for meat use. Not only the hides of wild cattle breeds, but also those of domestic cattle breeds used overseas are referred to as wild hides, since at the beginning of the global beef skin trade these hides mostly came from herds living in the wild in South America.

Well-known production areas have emerged where, on the one hand, the climatic conditions allow cattle to be kept on a large scale and, on the other hand, the meat can be used. This primarily applies to the South American countries, especially the La Plata countries ( Argentina , Uruguay and Paraguay ), which are therefore by far the most important. The importation of these hides to Germany probably began around 1900, especially by Hamburg merchants. Since the import of wild skins requires a wide range of specialist knowledge, this group remained relatively small.

Cattle hides are preferably used to make bags, boots and home accessories, and calfskins are preferably used for transition clothing. The vast majority of the hides are tanned into hairless leather (→ main article cowhide ).

The skins of adult animals are coarse and stiff and are therefore rarely used for fur purposes. For some time, African bull skins refined in Spain were used to make coats. Buffalo blankets were part of the traditional equipment of the North American natives.

For fur garments are mainly calf skins used, but this use in the modern age began in the 1920s.

Domestic cattle

Domestication as domestic cattle took place before the 9th millennium BC. Chr.

The cowhides produced in Europe are not sufficient for the local leather processing industry. Therefore, additional hides are imported, mainly from South America, Australia, East Asia, India and Africa. These hides, which come from domestic cattle but are known as wild skins, are usually smaller, coarser-grained and of coarser, tougher fibers than tame skins. (As of 1966). The term wild skins for the skins of the descendants of the cattle of the Criollo breed introduced by the Spanish in the 16th century in the southern parts of North America, in Central and South America, has long ceased to apply. The most important characteristic of these skins was the brand of the owner, the otherwise feral cattle. Above all, they made a very good sole leather. Since the meat was inferior, other races began to be crossed. In 1895, 50 percent of the cattle population consisted of criollos, in 1922 only 3 percent. In addition, purebred herds were already being kept, and as early as 1950 there were only a few really wild herds. Even for the North American, Canadian and New Zealand attacks, the designation "wild skin" was only used from tradition.

The coat sizes are very different depending on the breed. The coat colors also vary widely. Depending on the breed, they are monochrome yellow, yellow-red, red to dark red, red-brown, gray to brown, black-brown, less often red-moldy or white, often red, yellow-piebald and particularly often - for the very widespread lowland cattle and that already in GDR- Times there preferred bred black and white dairy cattle typical - black and white piebald.

The hair on the cowhide and calfskin is short, coarse and hard, and there is hardly any undercoat . The hair is more or less moiré. With predominantly stable housing and in warm countries there are no noticeable differences between summer and winter fur. The coat change happens gradually and over a longer period of time.

Breed characteristics, sex and age, way of life and climate are among other characteristics the factors that influence the quality of the hides on living cattle. The skin of female animals is usually finer and more delicate than that of the coarser and heavier of males. With increasing age, the sexual characteristics intensify, especially in breeding animals, particularly clearly in bull skin. The climatic conditions not only have a direct effect, but also indirectly through flora and fauna (cracks of thorns and cacti, insect damage, etc.). Since the same cattle breeds are often kept in closed breeding areas, the expert can draw fairly reliable conclusions about the quality of the hide and possible defects from the origin of the hide. Another quality-influencing factor is the treatment of the skin when it is extracted. Cuts that are too deep when peeling off make the skin “sleek”, inadequate or untimely conservation results in hard, “burned” areas; if the leather dries too quickly, the surface becomes dry, but rots inside.

The skins of adult domestic cattle are usually too heavy to be used for clothing. However, fur bags, fur boots, wall hangings, rugs and seat covers for the living area are made from cowhides or cowhides . In ancient times, cattle hides are said to have also been used to build canals.

In addition to the main suppliers Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay, there are other overseas hides exporting countries:

- The South American countries: Brazil , Colombia , Chile , Peru , Bolivia , Ecuador and Venezuela

- The Central American States: Panama , Costa Rica , Guatemala , Nicaragua , Mexico

- The USA and Canada

- From the Antilles: Cuba , Jamaica , Puerto Rico

- African areas: Abyssinia , Eritrea , Kenya , Rhodesia , South Africa , Natal Province , Transvaal , Namibia , West Africa

- Asia: India , Pakistan , Indonesia , China , Indochina , Burma and Siam

- Australia and New Zealand.

Domestic calf

Calfskin cloak of the bog body from Kayhausen

Bronze Age carrying sack made from untanned cattle hide from the Hallstatt salt mines

Calfskins are about 60 to 100 centimeters long (about the size of a foal skin). The hair is short and a little stiff. The coloring is very different: red-brown, brown, dark brown, red-brown-black-brown, black-white or brown-white. The fur is foal-like, but a moiré or wave pattern is rare, the hair is straight; the leather is heavier than the foal's skin . Only the softer pelts are used in significant quantities for fur processing. The skins come from animals slaughtered the same or a few weeks after birth, later the skins become too heavy. As with Persian broadtail, skins from prematurely born animals were sold under the name Galjak calfskins. The calfskins are used for jackets and coats, also for fur boots, hats, gloves, pillow cases, etc.

The State Museum for Nature and Humans in Oldenburg keeps a cloak made of calfskin, it was found in the Kayhauser Moor near the village of Kayhausen near Bad Zwischenahn in Lower Saxony and dates from the 4th to 1st century BC. It belonged to the so-called boy from Kayhausen - which one does not know for sure whether he was perhaps a girl - a bog body find from 1922.

In modern times, due to the lack of other fur material , jackets and coats began to be made from calfskin during the First World War ; until then they were used almost exclusively as leather. Knapsacks and suitcases were made from the skins of red-brown calves. Especially after the foal skin became fashionable, the cheaper and more readily available calf skin also came into the focus of fashion designers. Around 1925/26 the first natural piebald calfskin jackets were created in America, which achieved a very expressionistic impression . Philipp Manes also mentions the year 1925, when calfskins were made into coats for the first time. The type of fur was always in demand when there were import difficulties for other fur materials.

At the beginning of the main period of foal fur fashion , moiré calfskins were traded as calf foals , a designation that is no longer permissible according to the RAL regulations (the last word component must indicate the actual type of fur). Around the turn of the millennium, calfskin clothing from France was even falsely offered as a “pony” in one season. The calfskin can be recognized by the two neck vertebrae, the foal fur (including the pony ) by the "mirrors", the large hair vertebrae in front of the beginnings of the hind legs. During processing, however, the often annoying calfskin vertebrae are often removed by turning the headpiece, or these skin parts are not used.

At first the calfskin was hard-leather and "stubborn", it could hardly be processed into fancy furs. Nevertheless, around the time of the Second World War it was worn a lot, especially in Germany and Sweden. The rejection of the less elegant coats, however, soon became particularly evident in Sweden, around 1950 the women there refused to continue wearing calf coats. In other countries, especially Germany, the material remained somewhat more in demand. One of the reasons given was that larger sizes could be produced for women, "which also result in an acceptable fit for stronger figures and thus make the wearer appear slimmer". By means of new dressing processes, it was possible to cut the leather thinly in the foal's skin without damaging the hair roots, it became lighter and softer and thus got a cloth-like case. Improved fur finishing techniques made hair softer and shinier. The skins of just born animals came into stores as baby calf . There were also furs from unborn calves from deceased dams , which had a particularly fascinating moirée , they were traded as Teletta . A method already used with foals and horses was also carried over to the calf. The animals were shorn a few days before slaughter so that the blunt tips could grow back a little. Soon attempts were made, albeit unsuccessfully, to introduce the Russian name “Opoika” in retail stores as a more salable name for the product calfskin, "by resolution of a Leipzig working group", as a considerable number of cases had become known in which the word calfskin gave rise to unpleasant scenes had given .

It is mainly the rarer moiré and patterned, light types that are used for furs (1.8 to 2.1 kilograms). Interest in the inexpensive, but somewhat stiffer and not so attractive material waned between the world wars as prosperity increased. Only when fashion increasingly turned to flatter types of fur, especially the Persian , did calfskin also return. It was widely used during the war until well into the period after the Second World War . Many West German summer vacationers brought back coats made of sheared calfskin from the Spanish holiday resorts from the Greek furriers who settled there in large numbers, mostly unicoloured beige, brown or black and processed in combination with leather. Alongside the USA, the Federal Republic of Germany was the main customer for calfskin clothing around the 1970s.

The deliveries of calfskins come mainly from Northern and Central Europe and from South Africa and New Zealand, the latter two being best suited for fur purposes. In the beginning Danish and Swedish calfskins were mainly used, but later new, suitable types of calfskins were found in other countries of origin. The black-and-white and red-and-white skins came from Holland - a very light-leather and thin-haired product - which is characterized by a special sheen and effective drawing. At first, the black and white fur came as a shock to the fashion world, especially for après-ski and as sports fur, but it also proved to be suitable on other occasions and was accepted by consumers. The Bermuda calf was sheared and processed in its natural state; with its beige-brown color it looked similar to the then current Lakoda , a sheared seal skin , and was therefore particularly in demand. Pure white Belgian and French calfskins formed the ideal background for imaginative prints. In addition to the skins from European and overseas countries, Danish and Allgäu skins were still processed. The Allgäu fur could be dyed in many fashionable colors without having to be bleached to damage the hair. It is well moiré, with large spots and was therefore quite popular.

- Northern Europe: Finland, Sweden, Denmark and England

- Central Europe: Germany, Holland, Austria

- Eastern European varieties are larger, better drawn and lighter in the leather than German varieties.

- Other production areas mostly use the attack themselves.

- South Africa and New Zealand

- China , the skins from here are very small. A tobacco shop reported in 1952 that they were not traded in the fur center of Leipziger Brühl, at least not after 1927: “They were very cheap, but not interesting”.

Hair tends to break, especially if it is not of a silky quality, and is therefore not very hard-wearing. The durability coefficient for calfskin is estimated to be 30 to 40 percent.

Around 1950 the rule was: German calfskins available for fur purposes are either salted or dried when they are delivered. Salted goods are preferred, they result in better quality leather and have fewer failures in “balding”. The skins that are not too thick are used, they should be well preserved and not hairy. Small areas of damage are acceptable, but the skins should not be damaged by beetles. The quality assessment is based on the condition of the hair in terms of gloss and moiré. The better qualities have tight moiré, silky hair that is not too long. The lowest value are very smoke, matt, woolly or very flat skins without shine and moiré. Hearth signs cut into the hair also reduce the value considerably. Monochrome light or white calfskins can be colored differently and are therefore more usable than pied calfskins. Calfskins are not classified according to quality; they are only classified into colored and single-colored skins.

In 1988 it was said that the small quantities that had accumulated in the GDR were not of the selected quality that is suitable for fur purposes. They should come from very young animals because they have silky hair, are flat and well moiré. In principle, skins selected according to these criteria were no longer produced in the GDR. Half of the skins came from commercial slaughter, the other half from emergency slaughter. The ranges were divided into calfskins for leather purposes and fur calfskins. The fur calf skins were sorted according to quality classes A and B. The quality class A pelts were over 90 centimeters long, undamaged, tears up to 5 centimeters and a maximum of 2 damage, damage up to 2 centimeters in diameter were not counted. The skins had to be flat, moiré and at most half smoke. Quality class 2 was valid for skins under 90 centimeters with the same description. The pelts were salt-preserved, but sometimes not properly. The hair texture was very different, from sparse to stuffy, sometimes short-haired or dense and smoky, smoothly wavy and moiré. These were not skins as they were common in international trade. Although the raw assortments were carried out by specialists in the fur industry, the skins assigned to the fur calf skins comprised an average of 10.5 percent hairy skins, which, after drying, were forwarded to a company that used them to produce eardrums or parchment skins. Especially because of the dense and compact fiber structure and the relatively strong leather thickness, the GDR pelts required particularly intensive processing during fur finishing .

At the Leipzig fur market, the Brühl , packaged, salted veal skins were traded as " pugs ". The pelts were salted damp, rolled up and tied up. Rolling up was done by folding each hide lengthwise once, skin against skin. Then the fur was rolled, bringing hair upon hair. This bundle of rolls was then tied. The skins now had to be processed within four to six weeks to prevent them from becoming stuck. In winter they could naturally be stored longer in their raw state than at the higher summer temperatures.

In 1988 it said: Of the world attack - about which exact figures are not available - a maximum of 15% is suitable for fur purposes, i. H. a maximum of 30,000 to 50,000 pieces, which can be sorted out according to demand. - In the 60s and 70s there was great demand, after 1978 this flat skin was no longer in demand. Since around 2000, the article natural (fawns), but also fashionably colored, sheared, printed and also reversible has been in somewhat more frequent demand, especially for bags it has recently found greater use (2012).

- Calfskin clothing

Alice Ramsey (1886–1983) in a calf motorist coat

House yak

House yaks are more common in Asia. They are bred in the Pamir Mountains , Tian Shan and South Altai , occur in Mongolia , the western parts of China with Tibet and Nepal . The domestication began about the 1st millennium BC. Wild yaks now only live in the plateaus of Tibet, they are under strict protection.

The head body length of the skins of adult male wild animals is 280 to 325 centimeters, that of females 200 to 220 cm, domestic yaks are smaller. The coat color is dark to black-brown. There is a broad line of eel on the top of the head . The back and the mouth area are usually a little lighter.

The soft skins of the yak calves are suitable for making fur, but the skins of adult animals are too coarse for that. The yak is the only type of cattle that has a layered coat of hair. A distinction is made between a firmer outer or long hair, a coarser wool and a fine, spinnable under hair or fine wool. The hair of adult yaks, especially the long hair on the tail, shoulder and trunk, is spun and made into blankets, and wool for clothing is made from the hair of the young. The long outer hairs on the chest, tail and belly are also called horsehair in the yak, as they are similar to the hair on the tail and mane of horses. However, they are much softer than horses. The length of the hangings on the upper arm of Wildyaks is about 40 centimeters, and on the belly even 70 to 80 centimeters. Coarse wool hair with a length of 5 to 13 centimeters is distributed over the whole fur. As a third type of hair, fine wool can be found in all body regions, it makes up over 80 percent of the hair. In the sides of the fur, for example, there are 220 coarse hairs and 800 fine wool hairs per square centimeter. The head, neck and back are relatively short-haired. The tail is long-haired from the root. The forehead hair is twisted curly. The calves with their softer hair have no hangers. When changing hair, the yak mainly loses its wool hair. The failure begins in the neck and continues to the back and abdominal region.

Bison and other wild cattle

Bison or buffalo

- Whenever " buffalo skins" were mentioned in the fur trade , they always meant the fur of the American bison ( called buffalo robes in America ).

In hunting terms, the skins of the hoofed game are called blankets. The cover of the bison is softer in the leather than cowhide, the wool hair is fine and silky. Therefore, in contrast to the skins of most other cattle species, it is suitable for fur processing. The best skins come in autumn after the winter wool has formed.

The body length of this largest American mammal is up to 3 meters. The overdeveloped front body is further emphasized by the mane-like hair: the head, neck, shoulders, withers and front legs have hair up to 50 centimeters long and form large bulges on the forehead between the horns that tilt forward. They are designed as a hanging mane on the beard and dewlap and as forearm cuffs on the front legs. The color varies from dark chestnut brown to black brown, it is more contrasting than that of the bison. Occasionally there are white and gray and spotted pelts. The very rare white bison were considered sacred by the Indians. The bison wool is very fine, silky and mixed with awns. The skins (silk or beaver skins), which were called “silk” or “beaver” at the time, have an unusual color, they are very dark and the whole coat is more evenly haired, the hair is particularly fine and has a peculiar sheen. They mostly come from a bison cow. These "silk buffalos" are even softer than white ones. "Black and tan" buffalo skins are uniformly black, with the exception of the belly, flanks, underside of the tail, inside of the hind legs, chin and the area around the muzzle , these fur parts are reddish brown.

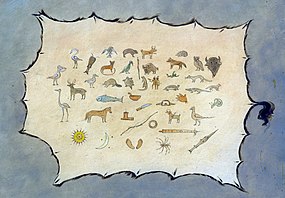

A characteristic of the members of various North American Indian tribes was the chief's coat made of buffalo skin. If the head of the fur was used as a headdress, this cap often still wore the horns of the animal, just as the ancient Teutons supposedly used the fur of the aurochs and bison . On the leather side of the coats or fur blankets , the deeds of the chiefs were painted in moving pictures. Because the hump of the mane was cut out, the fur looked like it was made of two parts. The buffalo skins could therefore usually be seen whether they had been stripped off by an Indian or a white man. The white hide hunter wanted as large a piece of leather as possible and therefore only cut the fur on the stomach. The Indian also made a cut along the edge of the back. He sewed these two halves back together after he had cut out the hump. The Native American work is easy to identify by this central seam. In addition to skin coats and other clothing, the Indians made blankets, canoe and tent covers from them.

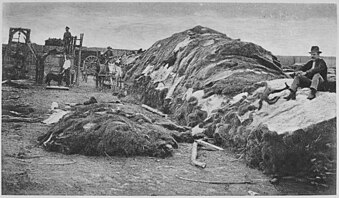

The Indians covered the frames of their canoes with buffalo skins, and they used the tails as fly whiskers. In 1863, the aboriginal and white buffalo hide trade was enormous. Hides and skins were stacked goods . Everyone had one or more skins, thousands were made into coats. Buffalo fur boots worked with the hair inside were common attire. A hide brought the inhabitants 3 to 10 dollars, painted and embroidered pelts (from the porcupine ) 50 to 100 dollars; however, the wages were often in kind instead of dollars. North American settlers and soldiers believed that one bison skin was more warm than four woolen blankets. The fur was often processed into coats for the American troops. The wool spun from bison hair would have been as fine as English sheep's wool. However, it was very difficult to win because the hair was very matted. In addition, the awns were very scratchy and very laborious to remove. The Indian women stretch and weave the wool for various purposes. During the Crimean War (1853 to 1856) the English court kürschner John Nicholay also offered American buffalo cloaks for soldiers at the front for 20 shillings under a contract with the government.

After the invention of the automobile, which at the time was mostly open and always unheated, a fashion with very lush motorist coats, preferably made of raccoon fur , emerged as a necessity . Up until this time, buffalo coats were also made for men and women, which were extremely durable. The furs were also used as magnificent carpets , as travel rugs and for camp beds.

Increasingly with the construction of the railways, a devastating hunt for the bison had begun, especially for meat, and later also for leather (buffalo leather for shoe soles and drive belts for machines), so that the once huge herds of an estimated 25 to 30 million animals were completely exterminated. In 1894, around 800 specimens lived in North America, around 200 of them in Yellowstone National Park as the last wild bison in the United States. Their number fell to a low in 1902 of only 23 animals.

There are now around 350,000 bison again in the American Midwest , a total of around half a million animals, so that the IUCN only lists the species as "near threatened". The bison population in Yellowstone National Park alone comprises between 3500 and 5000 animals.

In the Rocky Mountains ranches were created to breed bison, sometimes with several thousand animals. Various Indian tribes in the Plains also breed bison today. The world's largest population, held by the bison breeder Ted Turner , comprises 50,000 animals.

Muskogee Indians present a buffalo hide decorated with an eagle, the symbol of love and protection

Pawnee chief with leather-painted Buffalo robe (undated)

Medicine man in front of a buffalo skin

( undated )

- Replicas of painted buffalo robes of North American Indians

Musk ox

North American musk oxen were heavily hunted for their meat, the fur mostly only being used as a storage blanket. It was always quite rare in trade, due to the occurrence of the animals in the very remote areas of the far north. Only the Hudson's Bay Company put a small amount on the market annually (before 1911).

The long, dense fur of the muskox is composed of several different types of hair and extends almost down to the hooves. Above all, the very dense winter fur makes the animals appear massive. Towards the end of winter, this hair is faded and the coat color is predominantly yellow-brown instead of dark to black-brown. Light beige to yellow-brown hair colors can also be found on the saddle and feet. Individual animals and some populations also have light hair on their faces. Older animals are generally a little lighter in color.

At the base of the hair is a thick, 5 centimeter long undercoat made of fine wool. It covers all of the fur except for a small area between the nostrils and lips. On top of this lies a layer of coarse guard or guard hair that is much longer (45 to 62 centimeters) and mainly covers the rear, stomach, flanks and throat. The longest protective hair is on the throat. The coat changes between May and July. At birth, calves have a cinnamon-colored outer coat and an undercoat made of dark wool. The longer top hair first appears at the end of the first year of life. The undercoat of the musk ox is one of the finest natural fibers. In relation to its weight, it is eight times warmer than sheep's wool, it is as soft as the undercoat of cashmere goats. In Alaska attempts have therefore been made to domesticate musk ox as a wool supplier. The undercoat is combed out of the fur of the semi-tame animals by hand and processed into high-quality scarves and sweaters. The hair is spun, more recently, the wool is since about 1970 under the Inuktitut designation QIVIUT or Qiviut commercially.

Water buffalo

Attempts have also been made to use the skins of the African water buffalo . In contrast to the North American bison ("buffalo"), the attempts failed because of the stiff and heavy leather.

Bison

The bison is the only European wild cattle species still alive today. The ancient Teutons process the skins into blankets and clothing. The best coat quality is from October. The wool can be spun, but it is more scratchy than other wool and is therefore not really suitable for clothing.

The fur of the male animal has a head body length of up to 300 centimeters, the fur of female animals is considerably smaller. The tail is about 80 cm long and has brush-like hair at the end. The coat color is dark brown all year round, but slightly lighter in summer with the exception of the beard, head hair and tail tassel. The hair on the legs is black-brown. The neck and shoulder area has a light grayish-yellow overflown in winter.

The hair on the front body (head - without the area around the nasal mirror - neck, withers, shoulder, chest and upper part of the front legs) is long, more or less curled and shaggy on the head. The longest hair is in the head area on the forehead (up to 20 centimeters), temples, on the neck, and also on the throat in the form of a beard (37 to 40 centimeters). The long hair on the underside of the neck (18 to 25 centimeters) up to the chest form a hang, on the top of the neck to the withers a kind of mane. The rest of the fur is covered with close-fitting, short hair, as is the tail, except for the tassel of very long hair.

Today's wild populations of the bison all descend from ancestors that were reintroduced into the wild; they were extinct in the wild. They are under full international protection.

zebu

From the hump of the Zebu - or hump cattle are on Madagascar worked caps. Elsewhere, attempts are made to hammer in the hump in order to be able to use the largest possible piece of leather. Dried East Indian zebu skins were shipped as raw "Kips" ("East Indian Kips") or as vegetable half-tanned kips ("Indian Tanned Kips").

Deliveries from India and Pakistan are: Agra-Kipse, Purnrah-Kipse, Durbungha-Kipse, Dacca-Kipse and Meherpore-Kipse.

Items of skins with zebu humps that were created through cross-breeding came from central and northern Brazil, as the trade regretted, "unfortunately also with the Java skin, which used to be so popular, which used to come almost exclusively from straight-backed cattle."

Use, processing

- Designer bag and shoes made from jaguar-printed calfskin (Michael Kors, 2014)

Fully grown, especially South American cowhides with good color and appealing spots are used to make rugs, wall hangings and seat covers.

Calfskins are natural, bleached or dyed for jackets, coats, vests, capes, hats, bags, cases and similar small items as well as for home accessories. The skins, which are beautifully drawn in the speckles, are left in their natural state, such as those from the black and white lowland and pure white Simmenthal cattle.

Shorn calfskins are particularly suitable for printing. Patterns that imitate other types of fur, such as ocelot fur , leopard fur or zebra fur , are preferred , sometimes in simulated spots that do not occur in nature. But surveys from the textile industry such as plaid or houndstooth be adopted.

Depending on the fashion and model, around five to six calfskins are required for a coat. In classic fur processing, the pelts are first cut into one another in serrated or wavy seams ("incision") or sewn on top of one another ("put on") so that the skin connections are as invisible as possible from the hair side. The fur strips are then connected next to each other with straight seams or a wave seam. In order to reduce the resulting hair comb , the hair can be shortened with thinning scissors or a skinning knife before the longitudinal seams are sewn together, the outer hair must not be damaged. Far more common at the moment is the more cost-effective method, the rectangular assembly of the skins.

In order to reduce hair wear and thereby improve the durability of the calf clothing, the items of clothing are often combined with leather and possibly other materials. In particular, the edges are piped and the lower sleeves and underneath the torso sides are made of leather. Additional applications, for example a belt over a leather waist part, round off the overall look in a fashionable way.

A specialty among the items of clothing made of cowhide are the pampooties , heelless , lace-up fur sandals made by the Irish made of untanned cowhide, which were worn with the hair facing outwards. At least in the second half of the 20th century, they were cut and used by parts of the Irish farmers and fishermen themselves. Pampooties only have a short shelf life, usually less than a month, but they should be ideally suited for moving on the coarse stone rubble of the islands . Since the untanned leather becomes stiff when the pampooties are not worn, they have to be soaked overnight and put on when they are damp in the morning.

Because of the relatively low price and the smooth-haired structure of the calfskin, the pieces of fur that fall off during processing (heads, claws, sides of the fur) are used less, in contrast to other types of fur. If there is enough and if it makes economic sense, they are sewn together to form panels and are wholesalers as so-called “piece bodies” as semi-finished fur products . The ears of adult cattle are suitable for making brushes, especially for technical brushes (cattle ear hair).

- Calfskin processing

Dressing (tanning)

The for tanning coming rawhides can be depending on the pretreatment differ as follows:

- air-dried hides

- dry, arsenicized hides

- shade-dried hides

- shaved and stretched, literally: stretched and fleshed clean

- wet salted hides

- dry salted hides

- coated skins (skins coated with the so-called "khari salt", a naturally occurring, preserving earth).

Calfskins have a dense, strong dermis with tightly interwoven fiber bundles. The natural fat content of the dermis is low. In general, the technology of dressing fur skins differs from the classic fur dressing process in that the skins require a more intensive loosening of the skin fiber structure, a reduction in strength and weight than, for example, lambskins.

Larger skins of older animals are thinly cut in the leather (" fold ") and sheared. Shearing not only makes them flatter, but also gives them more shine.

Numbers and facts

Domestic calf and domestic cattle

- In 1612 the Wroclaw furriers were only allowed to make calfskin trimmings ("calf skins") for children's furs, but not for adults.

- January 1930 , Italian market report in The Tobacco Market

It scored:

- a) Calfskins

- Northern Italian guild goods

- without head short foot 3–7 kg bow approx. 4 ½ kg fresh weight Lire 11.25–11.50

- without head, short foot 3–8 kg bow approx. 5 ½ – 6 kg fresh weight Lire 10.00–10.30

- without head long foot 3–7 kg bow approx. 5–5 ½ kg fresh weight Lire 9.75

- per kilo fresh weight

- Northern Italian merchant goods:

- without head short foot 3–7 kg sheet approx. 4 ½ kg fold-free lire 11.50–11.70

- without head short foot 3–8 kg sheet approx. 5–5 ½ kg fold-free lire 10.50–10.75

- without head long foot 3–8 kg sheet approx. 4 ¾ - 5 kg fold-free Lire 10.20-10.50

- with head long foot 3–8 kg sheet approx. 5 kg fold-free Lire 8.75–9.00

- with head long foot 3–8 kg sheet approx. 5 ½ – 6 kg fold-free Lire 8.50–8.70

- per kilo fresh weight

- b) cowhides

- Northern Italian guild goods:

- Oxen 30–40 kg fresh weight Lire 5.15–5.25

- Ox of 40 kg fresh weight Lire 5.00–5.20

- Cows up to 30 kg fresh weight Lire 5.30–5.40

- Cows 30-40 kg fresh weight Lire 5.10-5.25

- Cows from 40 kg fresh weight upwards of 5.10-5.20 lire

- Heifers up to 25 kg fresh weight Lire 5.75–6.00

- Heifers 25–40 kg fresh weight Lire 5.10–5.50

- per kilo fresh weight

"Some of the best retailer goods even achieved prices like guild goods, lower provenances are of course correspondingly cheaper."

- In 1923 Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay exported more wild beef hides than all other countries combined.

- Before 1944 the maximum price for calfskins, natural and colored, was:

- best 55, - RM; a good 45 RM; medium 30 RM

- for calf head boards 50 × 100 centimeters 20, - RM.

- In 1956 Argentina exported salted cattle hides under the following names (for dried hides the weights are reduced):

- Barrigas (unborn): skins from unborn babies (embryos) with hair that is still undeveloped.

- Nonatos (unborn and newborn babies): skins with hair weighing up to 3½ kilos

- Mamones ( suckling calves): skins from animals of both sexes, weighing 3½ to 7 kilos exclusive

- Becerros (yearlings, calves): skins from animals of both sexes, weighing 7 to 11½ kilos, exclusive

- Vaquillonas (calves and young animals): skins from animals of both sexes, weighing 11½ to 18 kilos, exclusive

- Vacas (cow hides): hides weighing 18 kilos and up

- Novillos (ox skins): skins weighing 22 kilos and up

- Toros and Torunos (bulls): hides corresponding to this class.

- The following names also exist for Uruguay

- Becerritos : small calfskins

- Montevideo Americanos : beef hides up to a certain weight

- Pesados (overweight)

- Anchos : hides (as their name suggests).

- There are also quality labels such as Sanos , Desechos , Malesechos , Inservibles and Becerros Garrapata . The classification in these classes depends on the type and extent of the defect.

- 1957: Most of the calfskins are supplied by the USSR, then Poland. The number of Scandinavian and South American calfskins is much lower; German calfskins are only rarely processed into fur; they are generally too heavy-handed.

- In 1966 the calfskin consumption was "well over a quarter of a million" pieces.

- Before 1970 , according to information from the responsible party, the number of pelts was over half a million.

- In 1975 , coats made of calfskin, short-sheared by Hilchenbacher Pelzveredlung, were offered in clothing wholesalers as "Lakodakalb", named after the deep-sheared Lakodafell of the fur seal.

Bison and other wild cattle species

(According to G ARRETSON'S - the more cautious R OE looks at the numbers up to three times exaggerated):

- In 1803 only a few bison skins were delivered.

- From 1834 to 1844 , the American Fur Company in St. Louis bought 70,000 furs annually.

- In 1871 a company in St. Louis bought 250,000 skins for 40,000 thalers.

- In 1873 the oversupply was so great that the unit price had fallen to $ 1.25.

- In 1873 and 1874 , Forth Worth, Texas, sold 200,000 skins each in a day or two.

- In the winter of 1884 , as a result of the ruinous hunt for extermination, the price rose within two days from 5 to 25 and 30 and even more dollars. One winter later, even for $ 50 to $ 70, there was hardly any fur left.

- Before 1911 , around 500 musk ox skins were sold annually, averaging $ 25 per piece.

- In 1966 , tanned bison skins were sold to tourists in Elk Island National Park for 30 to 43 dollars, at the exchange rate at that time 120 to 190 DM.

- In 1988 , the Smoking Handbook on bison wrote: Attempts are currently underway to prepare the skins of women and young animals in such a way that they can be used for fur purposes, at least for trimmings. It is expected that at least 5000 skins from surplus animals can be sold annually, with meat and other by-products being used industrially.

- At the time, the number of animals kept in conservation parks was estimated at around 30,000. In addition, 15,000 bison were kept on farms, 3000 in the largest farm alone.

annotation

- ↑ The specified comparative values ( coefficients ) are the result of comparative tests by furriers and tobacco shops with regard to the degree of apparent wear and tear. The figures are ambiguous; in addition to the subjective observations of shelf life in practice, there are also influences from tanning and finishing as well as numerous other factors in each individual case. More precise information could only be determined on a scientific basis. The division was made in steps of 10 percent each. The most durable types of fur according to practical experience were set to 100 percent.

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Erna Mohr: From cattle hides and buffalo skins. In: "Das Pelzgewerbe" Vol. XVII / New Series 1966 No. 5, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 197-206

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i John Lahs, Georg von Stering-Krugheim: Handbook on wild hides and skins . From the company Allgemeine Land- und Seetransportgesellschaft Hermann Ludwig, Hamburg (Hsgr.), Hamburg 1956.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Heinrich Dathe , Paul Schöps, with the collaboration of 11 specialists: Fur Animal Atlas . VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena, 1986, pp. 283-289.

- ↑ Schöps, Häse: Calfskin (see there). Primary source L. Fougerat: La pelleterie et lé vêtement de fourrure dans l'antique, le préhistoire, les civilizations orientales, les barbaren, le grèce . Rome, Paris 1914, p. 192.

- ↑ a b c Friedrich Lorenz: Rauchwarenkunde , 4th edition. Volk und Wissen publishing house, Berlin 1958, pp. 136-137.

- ↑ Without the author's name: The fur fashion in winter 1961/62 - Madeleine de Rauch . In: Hermelin 1961 No. 5, Hermelin-Verlag, Berlin et al., P. 35 (Quote: "Madeleine de Rauch uses Galjak calfskins as a novelty ".)

- ↑ a b c d Fritz Schmidt: The book of the fur animals and fur . FC Mayer Verlag, Munich 1970, pp. 372-375.

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 1. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 132 (Note: In Volume 2, p. 132, he mentions it in the retrospective of the year 1926) ( G. & C. Franke collection ).

- ↑ a b c d V: Calfskin gave fashion a new impetus . In: Die Pelzwirtschaft Issue 9, September 1966, pp. 26-27.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XX. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1949. Keyword “Kalbfelle”.

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 2. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 146 ( G. & C. Franke collection ).

- ^ Oeconomicus: Quiet March in Berlin . In: “Pelzhandel”, 3rd year, March 1927, Sächsische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Christian Franke / Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel's Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 . 10. revised and supplemented new edition, Rifra-Verlag Murrhardt, pp. 250-253

- ^ David G. Kaplan: World of Furs . Fairchield Publications. Inc., New York 1974, p. 159.

- ↑ Richard König : An interesting lecture (report on the trade in Chinese, Mongolian, Manchurian and Japanese tobacco products). In: Die Pelzwirtschaft No. 47, 1952, p. 50.

- ↑ Paul Schöps; H. Brauckhoff, Stuttgart; K. Häse, Leipzig, Richard König , Frankfurt / Main; W. Straube-Daiber, Stuttgart: The durability coefficients of fur skins in Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume XV, New Series, 1964, No. 2, Hermelin Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin, Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig, Vienna, pp. 56–58.

- ^ Siegfried Beyer: For the assessment of fur skins . In: The fur industry , Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin / Leipzig 1951, issue 1/2, p. 4.

- ^ Rolf Andree, Günter Fischer, Christian Kniesche, VEB Sachsenpelz Naunhof: The use of modern technologies in the processing of calfskins in the GDR (lecture on the occasion of the II. International Fur Conference in Jasna, ČSSR). In: Brühl No. 29, January 1, 1988, p. 31, ISSN 0007-2664 .

- ↑ a b Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse: Kalbfelle . In: Das Pelzgewerbe 1955 vol. VI / new series, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, pp. 169–171

- ↑ a b Jürgen Lensch, Peter Schley and Rong-Chang Zhang (eds.): The Yak (Bos grunniens) in Central Asia , Gießen Treatises on Agricultural and Economic Research in the European East, Volume 205, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-428-08443 -8 , pp. 77, 78, 81, 217.

- ^ A b Heinrich Lomer : Der Rauchwaarenhandel , Leipzig 1864, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Elizabeth Ewing: Fur in Dress . BT Batsford Ltd, London 1981, p. 105 (English).

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XVII. Tape. Alexander Tuma publishing house, Vienna 1949. Keyword “Bison”.

- ↑ a b c Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition, published by the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, pp. 678–679.

- ^ White Buffalo Hunt Causing Uproar Throughout Indian Country Will Stop , Indian Country, March 7, 2012.

- ↑ Turner Ranches FAQ ( Memento of November 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Simon Greger: The furrier art . 4th edition, Bernhard Friedrich Voigt; Weimar 1883, p. 10. (130th volume in the series Neuer Schauplatz der Künste und Handwerke ).

- ↑ books.google.de: KH Gustavson: Die Kombinationsgerbung, chapter East Indian kipsis and furs. In: Handbuch der Gerbereichemie und Lederfabrikation , second volume, second part, mineral tanning and other not purely vegetable tanning types: The tanning. , Verlag Julius Springer, Vienna 1939, p. 619. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Ferdinand K. Kopecký: Ostindische Kipse. Jettmar Verlag, Prague 1916 (reference only, not used here).

- ↑ Rudolf Toursel : The calfskin jacket. Düsseldorf, April 1965.

- ^ AE Johann: Ireland . Heyne Verlag, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-453-01935-0 , pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Lucas AT. Footwear in Ireland. County Louth Archaeological Journal. 1956; 13: 309-394. Quoted in: R. Pinhasi, B. Gasparian, G. Areshian, D. Zardaryan, A. Smith, G. Bar-Oz, T. Higham: First direct evidence of chalcolithic footwear from the near eastern highlands. In: PloS one. Volume 5, number 6, 2010, p. E10984, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0010984 , PMID 20543959 , PMC 2882957 (free full text).

- ↑ T. Sadowski, J. Mikusiṅski: The tanning of calfskins for the production of fur products . In Brühl September / October 1978, VEB Fachbuchverlag Leipzig, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Fritz Wiggert: Origin and development of the old Silesian furrier trade with special consideration of the furrier guilds in Breslau and Neumarkt . Breslauer Kürschnerinnung (Ed.), 1926, p. 115, book cover and table of contents .

- ↑ Italian market report. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 6, Verlag Der Rauchwarenmarkt, Leipzig January 14, 1930, p. 2.

- ^ Ludwig, after E. Wenge: The wild skin and kips trade . Berlin, 1932, p. 18.

- ^ Friedrich Malm, August Dietzsch: The art of the furrier. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1951, p. 41.

- ↑ In: Fur mirror 1975 Issue No. 7 & 8, CB-Verlag Carl Boldt, title and table of contents..

- ^ Martin S. Garretson: The American Bison. The story of the extiction as a wild species and its restoration under federal protection. New York 1835 (primary source after Mohr, engl.).

- ^ Frank Gilbert Roe: The North American Buffalo. A critical study of the species in its wild state. University of Toronto Press, 1951 (Mohr primary source).