Parish Church of St. Gervasius and Protasius (Sechtem)

The parish church of St. Gervase and Protasius the Catholic church Sechtem is located in one of the larger districts of the left bank of the Rhine-Sieg district town of Bornheim in North Rhine-Westphalia . The church is likely to be a successor to the oldest Christian church in the region. A commission headed by the Royal Prussian municipal architects Schopen and Werner was responsible for the construction of a present-day parish church, which was built on the same site as the medieval church . They realized the designs of the architect Peter Josef Leydel (1798–1845), who died in 1845 and who designed them in the neoclassical style he favored in 1842, by completing the new building in April 1848 in just under two years. The parish church, which was consecrated to Saints Gervasius and Protasius , is one of the many listed buildings in the city of Bornheim.

Location of the Kirchberg

Almost the entire district of the place extends in a depression between the foothills and the Rhine , from which only the so-called Kirchberg or Nikolausberg stands out in the southwest of the old town center. The parish church and the adjacent chapel, consecrated to St. Nicholas , stand on this hill, which was created in Roman times - probably for military purposes - but has been eroded over the past almost 2000 years . The historic buildings, formerly enclosed by a churchyard, are located on the former Kirchstrasse between Krausplatz, Brusselser Strasse and Straßburger Strasse, which runs on the north side of the church.

Beginnings, findings of archeology on Kirchberg

The historic church site in the center is said to have been the location of a square fort within a Roman settlement. This assumption is supported by the extraordinarily large amounts of Roman masonry found in Sechtem during excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as the diverse artifacts recovered from daily life at that time. One of the burial places of late antiquity found in the Rhineland ( Germania inferior ) is the Sechtemer Kirchberg, whose graves and only partially recovered holy stones of the matrons came to light through the construction of the new church. In addition to several matron stones of the Gallo-Roman-Germanic mother goddesses that had remained in the ground and were also walled in, some specimens were also recovered, including one that had been dedicated to the goddess Amanda. In addition to the church foundations resting on Roman masonry and the building material of the former old church, a villa rustica , which was still inhabited around the year 400, and a Frankish tombstone of the boy Godewin from the middle of the 7th century with a well-preserved inscription have been discovered Century. The inscription not only proved the early existence of the village of Sechtem, but also the existence of a Christian church with burial rights (baptism, marriage and burial rights were long incumbent on the parish church) and shows a certain continuity of settlement and religious life .

From pagan places of worship to the Christian church

The first discovery of an ancient consecration stone is documented in Sechtem for 1845. The high number (previously five) salvaged consecration stones or altars, which were salvaged by recent research, but also by Maaßen in 1885, which had been consecrated to the Roman god of trade, Mercury , were mainly found in the area of the church, chapel and rectory of the town. The finds led representatives of Roman provincial archeology to conclude early on that there was a larger Mercurius - sanctuary of the ancient "ad septimam leugam". In addition to these finds in the area of the Nikolauskapelle, a matron stone was uncovered in 1975, and more recent research results from 1999 confirmed the presence of a mithraum on the area of a Roman estate in the southwest of the village. Apparently the sanctuary was destroyed by Christians around the year 400 after an official ban on pagan cults , possibly issued by Theodosius . From the worship of various deities of the Romans and then following mixing pagan-Christian forms of worship , the forced into Frankish-Carolingian developed Christianity and was in the form of the Roman Catholic Church as the state religion.

Patronage

The first named title patron Gervasius and the other patron of the Sechtemer church Protasius are said to be Milanese martyrs who were raised in 386 by Bishop Ambrosius . After the survey year, the relics of both martyrs are said to have spread rapidly , which led to the formation of a number of cathedral patronages for the two patrons in the Roman-Franconian Gaul (northern France / Belgium). The double patronage of Saints Gervasius and Protasius had its heyday during the time of Gregory of Tours . In the later Merovingian era, the choice of this patronage was no longer proven and, compared to other patronages, has remained a rarity in the Roman Catholic Church in Germany until today . For the entire Rhineland, for example, Gervasius's patronage only survived in Trier. It was the late antique church of Alt-Gervasius, which was built in the Roman imperial baths and was mentioned in sources from the beginning of the 12th century. Another thesis on the origin of church patronage says that a women's monastery based in Soissons had already founded a settlement in early Keldenich , whose Benedictine nuns were also subordinate to the Notre Dame Abbey. This monastery on the edge of the foothills was considered to be wealthy, and one of the monastery courtyards - the Sechtemer Landskroner or Stapelhof - was within sight of the local parish church. Possibly it was nuns from Soissons who then brought the local diocese patronage to Sechtem.

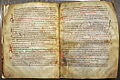

Parchment documents and stoneware

Godvine stone

The Franconian tombstone mentioned above, which only appeared in the Cologne art trade in 1944, is only preserved as a fragment of white sandstone and has a remaining size of approx. 16 × 25 × 7 cm. The inscription on it must therefore be regarded as incomplete, but gives extremely important details. According to the style, the script was classified as the vocalism of the early Carolingian vulgar Latin, a categorization that was corroborated by further characteristics of the typeface. The text contains the name of the person buried and the rare indication of the title patron of the church at the place of burial. The church historians Wilhelm Neuss and Paul Heusgen saw the Sechtem church or its former cemetery as a site of discovery. The Godvine stone is also evidence of an early parish church, as (as before) only one of these was granted the right to be buried. The inscription reads:

"[+] Cundetur hu

[c] tumulum in

basileca s (an) c (t) i Gervasi

Godv <i?> Ne carus

[pare] ntebus vix-

[lit ..."

According to the author Hemgesberg , a cast of the sandstone tablet is said to be in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn , a photograph in the treatise shows inventory no. 44.263 in the subtitle

Dietkirchen

Sechtem's economic and spiritual relationship was first documented in 1113. A more casual mention was found in a document (Dietkirchen document no. 3). of the monastery of the Benedictine nuns St. Petrus in Dietkirchen (Bonn), founded in the years 1000 to 1015, in which a witness named "Winrich de Sephteme" (a servant working for Dietkirchen) confirmed the content of the document text along with other witnesses. Documents of the former Dietkirchen canonical monastery, which emerged from a Benedictine monastery, date from 1015 (monasterio bunne constructo) and 1021 (Church of St. Peter in Tiedenkireca). They document the beginnings of the later women's monastery . Its early possessions were mostly tenant manors with their lands, which were often (but not only) located in the foothills region and were managed by Halfen . Sechtem's local and church history was closely connected to Dietkirchen, the patron saint of his church, and dates back to the first quarter of the 12th century. It is evidently supported by documents. For example, the abbess and convent of the Dietkirchen monastery / monastery had the right to present and other rights in electing parishes in Sechtem as early as 1166 . Since the early Middle Ages, Sechtem had to pay a tithing fee to the Bonn monastery / monastery for centuries: his former tithe barn , which was managed by the Halfen des Ophof, is now in the open-air museum in Kommern . The early tithe was by Pope Calixt III . been confirmed. As a result, Dietkirchen acquired further influence in Sechtem, which it was able to exercise through the favor of high clerics . In 1279 the Bonn convent leased the Rottzehnten in Sechtem and Urfeld , which the Cologne collegiate monastery St. Georg had previously received. In 1307 Archbishop Heinrich II undertook an exchange of goods with the consent of the cathedral chapter by giving 103 acres of arable land near “Sechteme” to Dietkirchen in exchange for land near Honnef . At that time Heinrich's sister, Ponzetta von Virneburg, had become the abbess of the canonical monastery. Since 1113, the former monastery has also been documented as the landlord in Urfeld (adjacent to Sechtem).

Rolduc Abbey

1122 is said to have died during a stay with Sechtem Ailbertus von Antoing . The priest and founder of today's Augustinian Canons Abbey Klosterrath in the province of Limburg traveled to the foothills region probably in connection with the properties of his Abbey Klosterrath there and, in addition to administrative reasons, also served the visit of his friend Count von Saffenberg. Like other pens and medals, the abbey marked its land in the Bornheim field with boundary stones on which its monogram was located. This is also the case in the Klosterrath case, where the letters "A R" = Abbey Rath or Abbey Rolduc could be found under a small cross. The abbey, also known as Klosterrath, today in the Dutch province (Netherlands), had developed from a donation from Count Adalbert von Saffenberg (also lord of the complex in Sechtem, later known as the Gray Castle) into one of the wealthiest abbeys. The convent, as well as pens from Cologne and Bonn, owned lands in the area of today's Bornheim very early on.

The boundary stone from the Bornheim district was once used to determine the boundaries of spiritual property and bore the initials of the Rolduc monastery. Its founder Ailbertus had his burial place in the chapel next to the parish church until 1771. It shows how much life in the real up to secularization was determined by the church. It is a chronicle of the Rolduc Abbey from the year 1122 (the Annales Rodenses ) from which it emerges that at that time there were already two churches in the center of the village, which were probably built in Frankish times. Today's small Nikolauskapelle, renewed in 1770/71, is said to have been the first parish church. This information on the early days of the churches is corroborated by the inscription on the above-mentioned Franconian tombstone, probably recovered in Sechtem (a cast is now part of the inventory of the LVR Museum Bonn), but also the ascertained Roman stone material from the previous church, which was demolished in the 18th century.

Reports on the early parish

Around 1122, the rule of Sechtem is said to have come into the possession of the Lords of Saffenberg (later Counts of Saffenberg), a period in which the Annales Rodenses reported of two Sechtem church buildings. The larger one is said to have been a towerless stone hall structure (the archetype of a hall church ), the masonry of which is said to have largely consisted of reused Roman cast iron ( opus caementicium ). In addition, one of the early clergymen of Sechtems is known from 1249, who was mentioned as Pastor Heinrich in a document as a witness. This information from the 13th century is only followed by the first mention of the rectory in 1426. After that, information on the church buildings in the village was not found again until the 16th century, which reported on the further development of the church and parish.

Regulations for construction loads and maintenance

After the decline of the private church system in the 11th and 12th centuries, a separately administered organization of church property developed , the regulations of which could be very different in the parishes. Since ancient times the parish of Sechtem consisted of two districts, so that the regulation of the maintenance costs was difficult. Since there was often disagreement among the parties responsible for building maintenance, nothing happened for a long time and the building fell into disrepair. According to the synodal statutes, the pastor was responsible for the maintenance of the choir , the owner of the big tithe for the maintenance of the nave, the parish (Sprengel) for the tower as well as for the churchyard wall and the ossuary . The ossuary was on the church's own land, on the churchyard surrounding the church. This was first mentioned in a report in 1687, when on the occasion of a visitation the incomplete enclosure of the churchyard was criticized and it was also ordered that the ossuary should be closed. This year is also the time when the parish cemetery was first mentioned. Apparently, however, it took a long time before the new regulations of the council resolutions were also applied in the small rural communities. The medieval church, which is said to have been a Gervasius church, fell into disrepair. It is not reported who bought today's baptismal font (a stone basin supported by columns), which was partially revised but originally Romanesque , and when it became an inventory of the old parish church.

Events between the 16th and 18th centuries

A decade before those von Sechtem died out, Arnold von Siegen in 1530 acquired the glory of Sechtem , including the gray castle in Sechtem, known since ancient times as "Gravenburg" , with all rights and duties (including the concerns of the Nikolauskapelle) from Siegen from Cologne. Arnold von Siegen, who had been raised to the nobility by Emperor Karl in January 1527, had now become Herr zu Sechtem, a title that the von Siegen inherited until 1734. Although the von Siegen owners of the Kirchberg and the chapel there, they should not have been formally responsible for the state of construction of the parish church. However, they probably appeared as generous donors, as a later visit report noted: “There is a tomb of Lord of Siegen in the choir”. A burial in the immediate vicinity of the altar and the holy of holies was an honor that was mostly only granted to the nobility who showed their appreciation through foundations. It was believed to be able to influence the salvation of one's soul in a positive way and trusted in the prayers promised by the foundation in soul masses of the responsible clergy.

In the time span of the two centuries there are further mentions of the church building, which were found in two visitation reports. Such an inventory of the Sechtemer church was drawn up for the first time shortly after the Council of Trent in 1569, and again about a hundred years later (see below). In its report, the first visit had described the poor state of the little church in drastic terms. For example, the commission said that “there is no house in the whole district that is uglier to look at”. The harsh criticism was evidently successful, because in 1607 the church was given a clapboard facade and a wooden tower made of half-timbering, for the construction of which wood was felled in the area of the Münstereifel forest . For material and carpentry work (including the transport and wages of his journeymen Ploch, Werker, Coinsen and Zimmerman), tower master Michaltz from Münstereifel received 601 ½ Dahler and 3 Albus from the municipality that was obliged to build . At the same time, a bell was specially cast.

Visitation of the interior of the church

Another visit is reported for 1687, which mentions details of the interior of the church. It says in contemporary style: “The honorable gentlemen visiters drove from Keldenich to the village of Sechtem. They held high mass and gave the blessing. Then they visited ... ”. The visitors reported that three altars were found. The St. Gervase and Protasius consecrated main altar hid in the tabernacle closed hl. Hosts and a silver monstrance covered with gold (a donation from the Lord of the White Castle), and a silver ciborium were also part of the church treasury. That of St. The side altar consecrated to Anna was reserved for the Vicarie , who had their own income. The second side altar was dedicated to Mary , the Mother of God . For him there were obligations of several trade fairs, for which three gold marks were paid out of the yields of certain vineyards. There were also comments on the baptismal font found. It was said that it was coated with lead and that there was a crack in it, and that the lid was missing. The walls or ceiling of the Gerkammer seem to have been damp, because the visitors urged that the damaged areas of the roofing be replaced. At that time there was no information about the construction of the nave and choir.

The altarpiece of the Nikolauskapelle

In the Nikolauskapelle, which was demolished in 1768/69 and renovated in 1771, there was an altarpiece, which was probably made in the middle of the 19th century. It was relocated on the occasion of a restoration of the interior carried out in 1901. Whose representation of St. Nicholas at first glance dominates the frame. It is the work of an unknown artist, which on closer inspection (after a professional restoration) reveals details that had not been taken into account until then. On the left edge of the picture shows a miniature of the medieval parish church of Sechtems, the original spire of which burned down in 1784 and then, having become dilapidated, was demolished in 1843/44.

Transition into the 19th century

A fire from a neighboring building in 1784 spread to the church. He seized the wooden church tower and damaged him and his bell so badly that the tower became dilapidated and the bell was unusable. Further documents from 1687 have been preserved. After this, the community concluded a contract with the bell founder Waßenberg, in which master Matthias committed himself to casting a medium bell. Since the contract warned that payment for the casting of the big bell would be in default, an extension of the ringing at that time to three bells is assumed to be likely. The affiliation of the parish church to Dietkirchen Abbey came to an end with the secularization . According to the historian Paul Clemen (publ. 1905), the church had a bell with the following inscription:

"S. ANNA BEY YOUR DAUGHTER'S CHILD ASK FOR THOSE YOUR SERVANTS ARE.

M. ANNA LB DE BOURSCHEID, ABBATISSA IN DIETKIRCHEN.

PETRUS LEGROS FECIT ANNO 1785 "

In addition to a roof repair that was also documented in 1785, it was probably the last donation from Dietkirchen Abbey to the Sechtem parish church.

French period

In Napoleonic times , the areas on the left bank of the Rhine belonged to France. The French territorial division, the constitution and the legal system of the French Republic applied. The Concordat concluded in 1801 between Napoleon and Pope Pius VII, including the attached Napoleonic articles, also applied in the departments of the area on the left bank of the Rhine that were now established. In 1802 monasteries and monasteries were abolished, spiritual property confiscated and nationalized, and many a church was profaned . This also affected the parish properties in Sechtem, which were confiscated and leased. These were measures that directly affected Sechtem. With the end of the feudal period, the elimination of the interest rule of the Dietkirchen monastery and similar feudal rule was essential.

Reorganization of church conditions

The reorganization brought the end of patronage rights. Each canton received a main church, to which the Brühl parish church of St. Margareta was designated as the canton church in the canton of Brühl - to which Mairie Sechtem belonged. This was subordinate to a senior pastor (Curé) who was in charge of the individual parishes (auxiliary parishes) of the canton. Problems arose with the establishment of the auxiliary parishes, as the French state was only willing to pay a certain number of auxiliary pastors. The reallocation of the parishes, which was determined by the Aachen Bishop Berdolet and the Prefect of the Roerdepartements , only came into effect after a 1804 survey of the Maires in Brühl and an estimate of the incomes of the individual parishes by a notary in 1805, in which the number of Auxiliary parishes was increased.

The 1804 interviewees also included the former Ophalfe Peter Bollig, who had been appointed Maire Sechtems in 1800 . With diplomatic skill, he succeeded in maintaining the Sechtem Church of St. Gervasius and Protasius despite the desolate state of construction of the church and the precarious situation of the church factory as an auxiliary parish.

The Nikolauskapelle, which was rebuilt in 1771 after the demolition of a previous building , belonged to the secularized buildings and was threatened with demolition. Peter Bollig managed to preserve the chapel by making it a Maison de Mairie from 1804/05 to 1809 (e.g. opening larger, rectangular windows). Later, beyond the time as a French department, the official residence was again in the neighboring house of the Ophof until 1821, and the chapel was again used for religious purposes. Bollig, who also used his office to protect the church buildings on site, is still a highly respected citizen in the history of the place. In 1803 619 people lived in the Mairie Sechtem , in which only the Rösberg Church was doing comparatively well. The fact that in 1812 a request for aid was made by the Sechtem church council to finance the fuel for the Eternal Light illustrates the financial situation of the community at that time.

19th and 20th centuries

Under Prussian administration

A report by the then state dean Dreesen had stated in a visitation protocol from September 1829 that the church tower of the parish church was in an extremely desolate condition. Dreesen noted that the community had not yet taken any precautions to counter a possible collapse of the tower and recommended an inspection by a building official belonging to the Royal Prussian government. Since it was feared that the ringing of all the bells could cause excessive vibrations that would cause the tower to collapse, the church council also advised the mayor of this danger. The board of directors argued that the ramshackle tower framework could not cope with another full bell and asked for understanding for a temporary suspension of the bell. Ultimately, it was recognized that a new church would be inevitable, and planning began accordingly. After the churches and the responsible school administration in Cologne had given their approval in October 1830, the bells began to be removed and an emergency scaffold was erected for them, then the endangered tower was demolished in 1834. The demolition of the medieval church followed about 10 years later in July / August of the year 1844. In the meantime - from the demolition of the old church to the completion of the new parish church - the services were held in the provisionally prepared Nikolauskapelle.

New construction of today's parish church

From the tenders for the construction of a new parish church in Sechtem, the decision was made in favor of the proposals made by Bonn university architect Peter Josef Leydel. He had proposed a building in the classicism style , which was agreed upon after making some corrections and changes. After Leydel died in July 1845 before work on building the new church began, the building was carried out by the royal municipal builders Schopen and Werner.

Construction segments, extensions and conversions

According to Leydel's plans, an elongated, east-facing , clearly structured hall church made of brick was built . The church construction begins with a tower in front of the nave and ends with a suspended round choir flanked by extensions (sacristy, chamber of paraments ). Since a vaulting of the interior ceiling was not planned, the buttresses previously required on sacred Gothic buildings on the flanks of the building could be omitted. The elongated hall building under a gable roof received three dormer windows on both sides and the rounded hipped roof of the choir one dormer. A superimposed floor plan of the old and new church contained in Vorzepf's chronicle illustrates the changed dimensions of the buildings and also provides a legend of archaeological sites on the building site. In 1903 the entrances on the front were renewed. The main and secondary portals were given rectangular concrete frames, which are noticeable because they remained on the rest of the building without the decorative brick panels.

tower

The late Classicist square tower in front of it to the west, which is being built in a further construction phase, is integrated with the thickness of its walls in the front of the nave. It had received a provisional emergency roof in the winter of 1848/49. By the summer of 1852 at the latest, the construction of the church, including the tower, seems to have been essentially completed, as the consecration was carried out by Archbishop Geissel on June 1st of that year .

The tower is divided into three areas by a circumferential cornice. This is the ground-level entrance area with a large round window above the main portal, to which the second section with narrow rectangular windows arranged on all sides is attached. Of these small arched windows, only those on the front received additional border decorations. The third area is the bell storey and has four-sided sound openings. They are designed as double arched windows that rest on a kaff or cap cornice and are spanned by a common blind arch in the masonry. The tower's helmet changes into an octagon at its base of the square. As part of a long-term external renovation, sandblasting cleaning was carried out in 1969 and after removing a crack in the masonry, new grouting was carried out.

Bells

Master builder Leydel had erected an emergency scaffolding on the Kirchberg to accommodate the bells from the old tower. Since the scaffolding was left uncovered, the old bells were exposed to fluctuations in the weather for several years while hanging in the open and were damaged. Housed in the new bell cage, except for one, their uselessness had to be determined. The local council decided to add two bells to be re-cast to the received ones. After obtaining cost estimates, the Dubois company from Münster received the casting order. The bells (tone G. and F.) ordered at a price of 1,030 thalers were cast in the order year 1847 and delivered in 1848. With the existing St. Anna bell, which had the strike tone A., they gave the new bell a harmonious sound.

“Fondue PAR GB DUBOIS 1847.

WHEN THE WEATHER DONE SENDED

ALEXIUS GLOECKLEIN DOWN TO THE SKY.

ALEXIUS BELL WITH A

STRONG MOUTH

ERRORS EVERY HOUR, NEAR AND FAR, TO THE LORD'S FEAR. "

Dimensions: height 75 cm, ø 95 cm, weight 510 kg, tone F.

"DUBOIS FECIT ANNO 1847.

I AM MARY TO JESUS, I CALL

THE SUENDER, I ADMIT THAT HE CONVERT

AND ALWAYS CHOOSE THE BEST PART TO HONOR GOD AND OWN SALVATION."

Dimensions: height 88 cm, ø 108 cm, weight 810 kg, clay G.

40 years later, the bell founder Christian Claren from Sieglar was commissioned to cast the larger, cracked bells. During the First World War , the small Legros bell escaped delivery due to its historical significance, but three bells were confiscated for army administration purposes. Upon delivery to the Merten collection point, compensation of 2560.50 marks was paid.

The St. Anna bell, formerly donated by an abbess from Dietkirchen, remained the basis with its basic tone A. even with additions to later bells. This was then also the case with the new bells, the casting of which was commissioned in 1927 by the company Petit & Gebr. Edelbrock in Gescher, Westphalia .

In the winter of 1928/29, which was described as extremely cold, the historic little St. Anna bell burst. It was very cracked and unusable. A new cast ordered in 1933, also by Petit & Gebr. Edelbrock, created a duplicate, which received the same consecration name. The circumstances of the Second World War , which broke out six years later , meant that the bells were again confiscated in 1942, this time without compensation. The last new cast, the little Anna bell, remained in the tower for church services and fire alarms. After the end of the war, when a new bell had been ordered and received from the cast steel factory Bochumer Verein in 1947 , it went to the parish of St. Petri in Ketten in Lengsdorf . The four new bells are called:

- Tu Rex Christe Veni cum Pace / BVC 1947, No. 583, tone d

- Nos benedicat Mater Maria / BVC 1947, No. 492, tone f

- Sancti Patroni Custodite nos / BVC 1947, No. 523, tone g

- Sancti Wendeline adjutor sis / BVC 1947, no.548, tone a

Twelve years later, the church received an electric bell system, which made the strenuous manual ringing of several people with ropes superfluous.

Origin and change of the church interior

Just as the church bells changed over the centuries, so did the interior design change in the decades after the new church was built. This was done in the form of minor modifications, in the event of wear and tear due to the replacement of materials or equipment. In addition, there was an increasing prosperity among the villagers. This showed in the increased demands of the parishioners, but also in the willingness to get involved financially for the interests of their church. In December 1846 it was decided on the type of floor design. In general, the flooring should be made of square-cut panels, with material from Berkum stone (Hauberg) being selected for the area from the choir to the communion bench and stone from Andernach for the nave . The floor covering in the choir area, which was described as “totally worn out” in March 1887, was replaced in April with Mettlach mosaic tiles from Villeroy & Boch . In 1899 a local treasury funded the complete replacement of the flooring in the nave. The sides of the nave had large, high windows and the pillar-less interior was spanned by a flat, painted beamed ceiling, which underwent some changes over the decades. Among them is probably the one in the framework of a renovation under Pastor Ley (in office from 1898 to 1909), which includes the decoration of the ceiling. This received a white one on a blue starry sky, St. Giant dove symbolizing the spirit , spreading its wings wide. The distinctive depiction of the dove was applied just in front of the choir arch in accordance with a harmonious size ratio and the golden rays emanating from it ran, tapering in thickness, over several beam elements. A renovation carried out with the involvement of the monument authority at the end of the 1950s - under the competent direction of the Brühl restorer Gangolf Minn - saved the beamed ceiling system from the mid-19th century that is admired today by getting its former version back after the restoration of the beams. A central aisle lined with light stalls still leads from the western main entrance - an entrance is separated by lockable glass doors - beginning under the organ gallery, through the interior to the choir and the altars. The light-flooded nave can be seen from every point as there are no pillars to obstruct the view. The slightly higher level of the choir, the altar there, the two side altars and the confessionals set up on the left and right of the sides and the new pulpit acquired in 1875 for the price of 1080 thalers are all in the field of view of the visitors. The sound of the old organ also fills the room unimpaired, not least due to the technical advantages (acoustics) of a coffered ceiling . The Romanesque baptismal font and a delicate white marble sculpture of a Madonna in Gothic style (beginning of the 15th century), which is said to come from the secularized Benedictine monastery Königsdorf, are considered preserved, historically valuable pieces of equipment .

Window fittings

At the turn of the century, the windows of the choir and nave were renewed under Pastor Ley, who was mentioned as particularly art-loving. The central window of the three round windows of the choir was walled up (open again since 1956) and the side windows were adapted to the ten Romanesque windows of the nave. The initially simple glazing of the windows of the nave was fitted with artistic glass paintings between 1899 and 1901, which were gradually replaced and reproduced the motifs of the rosary. A large number of donors from among the community members were found to cover the cost of the ten individual works of art. The manufacturer and supplier was a Düsseldorf company. The church windows damaged by shell fire during the war, some of which were temporarily glued with cardboard, had to be renovated. In the autumn of 1951, the church windows could be re-glazed by a Bonn glassworks at a fixed price of DM 2000.

Altars

The first high altar in the new church had already reached the old Sechtem church during the French period . It was a marble canopy altar from the former parish church of St. Brigida in Cologne's old town , which was secularized in 1802 . After a renovation in 1848, it was installed in the new church as a makeshift. It was followed in 1864 by a stone high altar, which, after renovations in 1903, 1908 and its uncovering in 1939 (which also made a sacrament house behind it visible), was used until the 1960s. After the liturgical changes of the Second Vatican Council in Rome , the parish church was renovated from 1968 to 1976 and the high altar was dismantled. A new, now contemporary altar made of Wölflinger trachyte by the Cologne sculptor Hein Gernot is now used to celebrate mass.

Organ systems

Paul Clemen wrote about the first organ in a parish church in Sechtem: “The central part of the organ is a fine Rococo work with an attractive disposition ”. He used it to describe an organ manufactured by the Adolph Ibach company, which could be acquired cheaply as a used system in 1848 at a price of 1,050 thalers. The organ, which was temporarily installed in the Lambertus Church in Düsseldorf , was renovated in 1843 and in 1911 it was decided to buy a new organ from the Bonn organ builder Klais. After the trade-in for the old system, the remaining acquisition cost was 7400 marks. In 1917 the pewter organ pipes narrowly escaped dismantling due to the war, as the request made by the parish to keep the organ parts was supported by the then provincial curator Renard in Bonn.

Change in the Church Environment

Demolition of the medieval Chapel of St. Nicholas

The first defining change in the appearance of the place (and at the same time in the church environment) was the demolition of the old, dilapidated St. Nicholas' Chapel in 1768/69 by the new owner Heinrich von Monschaw . The chapel, which was demolished in 1771, had been replaced by a much smaller new building, according to a written description from the vicar and later pastor Müller. A bakery of the neighboring pastorate built on Nikolausberg is said to have been applanated during the work on the new building.

Parish office, old and new parsonage

income

The host of an office and residence, also known as a pastorate, was the pastor or pastor of a parish. A pastor Heinrich appears as the first official witness in a document from the Burgrave of Landskron, in which in June 1249 the Schillingskapellen monastery transferred a Hufe Land in Sechtem (from the former estates of the Benedictine Sisters OSB in Dietkirchen) as a fief. This endowment became the basis of a benefice that served to maintain the pastoral office. According to the Cologne historiographer Gelenius, this relatively modest endowment for the pastor's position had already turned into 21 acres of arable land in 1569 (it is said to have been allowances from the church tithing), which then, according to the pastor from 1784, increased to 66 5⁄8 Tomorrow lands had expanded. In addition, there was wood felling of 15 acres and a vineyard (church garden) and a tenth of a further nine acres. There was also a state salary of 240 marks.

Old rectory

A modest early parsonage for the pastors (vicars, pastors, pastors) of the Sechtem parish was mentioned in 1426 by Pastor Gobelin. A description from 1845 refers to the old, built over a vaulted cellar rectory as half-timbered buildings, except for the walled with brick compartments of the north gable whose walls, only one clay / straw mixture on Stakhölzern passed. The building was plastered with mortar and whitewashed to protect it from the weather. The two-story building had a balcony, brick roofing and slate surrounds. In the middle of the 15th century, Dietrich Vonk is listed as the tenth clergyman, who was pastor in Sechtem and pastor of the Dietkirchen monastery as vicar. This is evidenced by a document from 1457, in which he sealed a lease agreement for the Landskroner Hof zu Sechtem, between Johann Hauft van Berge (Berge = today's Walberberg) and the owners of Ritter Lutter Quad Herr zu Tomburg and Landskron and Junker Johann von Eltz with his church seal . The Luxemburgish Nikolaus Schröder was chaplain in the Cologne parish church St. Brigida in Cologne in 1749 and in 1762 he was pastor in Sechtem and was transferred from there to Rüngsdorf near Bonn. This explains why the high altar made its way from the parish church of St. Brigida to the parish church in Sechtem.

Today's rectory

The new rectory of the parish of St. Gervasius and Protasius was built in the 1870s on the area of the parish farm buildings and took the place of the old barn. With this, since agriculture had been practiced since ancient times, all utility buildings - for example horse, cow and pig stalls - were publicly auctioned and sold to the highest bidders for demolition.

The successor to the old rectory is said to have been based on sketches from the St. Peter's rectory in Vilich. Following his example, the building officer and municipal church builder Schubert (Bonn) had drawn up and presented plans at the end of 1874. The plans, the cost estimate of which included an estimate of 15,000 122.44 marks, were accepted and the new building was commissioned. According to contractual deadlines, the start of the work was set for March 1875 and the completion of the shell (including the roofing) was scheduled for November of that year. The final account should be made after a date set for July 1, 1876. The construction company Pütz from Limperich was able to meet the deadline and received (Vorzepf cites the Bornheim town archive as a source) from the civil community's own funds, a remaining amount of 16,397.86 marks. The first owner of the new building was Pastor König, who had been in office since 1873 and died in 1889. The clergy mentioned here are only a selection of the pastors of the Sechtem parish, who are known by name and who have been mentioned in a wide variety of documents over the centuries and can be proven almost completely.

Traces of old burial places

The poor condition of the old Sechtem churchyard surrounding the parish church - it was the church's own land - changed little over the centuries. The cemetery, popularly known as the cemetery of God in its beginnings (see burial law of a parish church), remained in a desolate condition even after the ossuary was torn down (see visitation 1687), the things that were further criticized were ignored and their condition had not changed in 1817. In a note on the churchyard from 1826: "The large wooden cross with a knee bench under the walnut tree, next to the place where the unbaptized children are buried, was erected by a widow." The separate burial place for children who died unbaptized was since Synod of Carthage in 418 solidified practice in the Catholic Church.

The size of the churchyard area had been reduced since the larger medieval structure of the parish church was torn down by the much larger new building by Leydel, and the later demolition of the old rectory with its farm buildings brought new open spaces, which apparently made it possible to sell the parish garden land elsewhere . This shortage of the old churchyard area meant that in 1883 a decision was made to enlarge the area, as a result of which 481 m² of the adjoining parish garden was acquired, which was followed by a final extension in 1896. After that, the cemetery was given a walled enclosure made of brick, the two entrances of which were adorned with pointed gables.

The earliest evidence of modern burials on the Kirchberg are four stone grave crosses from the 18th century, one of which is so weathered that no characters can be recognized.

1)

"A (NNO) 1705 THE 6TH AVGVST IS IN THE H (ERRN) SLEEPING OF THE VESTIBLE

BERNATVS BAVCH OF THE COURT OF SEXY WASTE SHEEPS VND OPHALFEN. GTDS "

2) Illegible, weathered

3) Inscription on the reverse

“A (NNO) 1760 THE 2 OCTOBER DIED THE

PROBABLY ACTBARRE HALBWINNER ANDREAS KALLEN

A (NNO) 17… .. THE… .. THE VIRTUAL WOMAN (ANNA OSTEN) DIED

4) Inscription on the back: 1729 17. 9BRIS DIED THE MUCH

AND Respectable ANDREAS URRBACH, HIS AGE 45

YEARS… .. 1760 ON THE 18th AUGU (ST) DIED THE VERY HONORABLE

ANNA NARIA B (ALSO) URBACH'S HALF-WINNER LAST UPHOFF "

The old churchyard, including its 19th century extensions, was closed on January 1st, 1959. At the beginning of the 1960s, the superstructures of the entrances were demolished and the wall of the abandoned cemetery was only partially left. In 1979 the last grave sites were leveled, tombstones dismantled and the remaining deceased reburied. Ultimately, the entire area was turned into a green area. Some commemorative plaques of deserving citizens from the old cemetery were embedded in the final property wall. In 1980 the remains of the cemetery wall were disposed of and in 1981 a parking lot was created on Straßburger Straße opposite the church and chapel for those who lived away from the church.

Pastoral care area Bornheim-Vorgebirge

Since a reorganization of the pastoral care areas, the parish of St. Gervasius and Protasius in Sechtem has been assigned to the pastoral care area Bornheim - Vorgebirge. Eight parishes were united in this area. The parishes of St. Albertus Magnus (Dersdorf), St. Michael (Waldorf), St. Joseph (Kardorf), St. Aegidius (Hemmerich), St. Markus (Rösberg) , St. Martin (Merten), St. . Gervasius and Protasius (Sechtem) and St. Walburga (Walberberg) represented.

literature

- Harald Koschick (Ed.) Archeology in the Rhineland: 2001, Publisher: Theiss, Stuttgart b2002 ISBN 3-8062-1751-3

- Paul Clemen : The art monuments of the city and the district of Bonn. (= The art monuments of the Rhine Province. Vol. 5, 3). Schwann, Düsseldorf 1905.

- Norbert Zerlett, City of Bornheim in the foothills , Verlag Rheinische Kunststätten 1981, issue 243. ISBN 3-88094-349-4

- Norbert Zerlett, Landmarks in Field and Forest. In: Brühler Heimatblätter. No. 2/1978, p. 35.

- Horst Bursch, “The foothills from the Rhine to the Swist”, Sutton Verlag GmbH, Erfurt 2011. ISBN 978-3-86680-796-9

- Heinz Vorzepf: Sechtem village chronicle ,

- Volume 2: Church and School through the Ages. 2001.

- Volume 3: History of our homeland, castles and farms. 2008.

- Volume 5, - 900-year celebration -, 2016. Typesetting and printing: alka mediengestaltung GmbH, Bornheim

- Jürgen Kunow and Markus Trier, Archeology in the Rhineland 2014 , Landschaftsverband Rheinland, Office for Monument Preservation (ed.) And Roman-Germanic Museum of the City of Cologne (ed.), Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-8062-3214-1

- Thomas Paul Becker: Confessionalization in Kurköln. Investigations into the implementation of the Catholic reform in the deaneries Ahrgau and Bonn on the basis of visitation protocols 1583-1762. Röhrscheid Verlag. Bonn 1989, pp. 30-34. ISBN 3-7928-0592-8 / ISBN 978-3-7928-0592-3

- Heinz Cüppers, "Römische Baudenkmäler" p. 82, in: Patrick Ostermann (arr.): City of Trier. Old town. (= Cultural monuments in Rhineland-Palatinate. Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany. Volume 17.1). 1st edition. Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2001, ISBN 3-88462-171-8 .

- Helga Hemgesberg, Basilica sancti Gervasi . On a Merovingian grave inscription, in RHEINISCHE Vierteljahrsblätter. Notifications d. Institute for historical regional studies of the Rhineland at the University of Bonn.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Norbert Zerlett: City of Bornheim in the foothills . Ed .: Rheinischer Verein für Denkmalpflege und Landschaftsschutz (= Rheinische Kunststätten . Volume 243 ). Society for book printing, Neuss 1981, ISBN 3-88094-349-4 , p. 18th f .

- ↑ a b Paul Clemen in “Sechtem, Roman Finds”, p. 365 ff

- ^ German Hubert Christian Maaßen: History of the parishes of the deanery Hersel (1885)

- ↑ Paul Clemen in “Sechtem, Roman Funde”, p. 365, with reference to August Oxé , in “Ein Merkurheiligtum in Sechtem” Bonner Jahrbücher, Volume 108, p. 246

- ↑ No. 0794/40, Bonner Jahrbücher Volume 175, 1975, pp. 328–329

- ↑ Cornelius Ulbert and Johann Christoph Wulfmeier: Mithras in the foothills. New finds from Sechtem (= archeology in the Rhineland . Volume 2001 ). Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, p. 54-56 .

- ^ Helga Hemgesberg in: Basilica sancti Gervasi . On a Merovingian epitaph, pages 325–334

- ^ Heinz Cüppers: Roman architectural monuments. P. 82, in: Patrick Ostermann (arr.): City of Trier. Old town. (= Cultural monuments in Rhineland-Palatinate)

- ^ Helga Hemgesberg: Basilica sancti Gervasi . On a Merovingian epitaph, p. 329

- ↑ The current information from the parish office confirms the whereabouts of the stone in the RLM Bonn

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: 900th anniversary celebration. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik, section Prehistory . Volume 5 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 2 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Burgen und Höfe, section Ophof (= Sechtemer village chronicle . Volume 3 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 340 ff .

- ↑ Dietkirchener Hof ( Memento of the original from July 28, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , City of Wesseling

- ↑ Norbert Zerlett: Boundary stones in the field and forest. Boundary stone 5.

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 138 ff .

- ^ Thomas Paul Becker: Confessionalization in Kurköln. Investigations into the implementation of the Catholic reform in the deaneries Ahrgau and Bonn on the basis of visitation protocols 1583–1762, pp. 30–34.

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: History of the Sechtem parish church (= Sechtem village chronicle . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 120 f .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Castles and Courtyards, Graue Burg, section Patronage (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 15 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Burgen und Höfe, Graue Burg, section Arnold von Siegen (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 3 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 284-290 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: History of the Sechtem parish church (= Sechtem village chronicle . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 9 f .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: History of the Sechtem parish church (= Sechtem village chronicle . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 21-24 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. Section Nikolauskapelle (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 257 .

- ↑ Fritz Wündisch, Brühl. Mosaic stones on the history of an old city in Cologne. Pp. 232-234.

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Burgen und Höfe, section Ophof (= Sechtemer village chronicle . Volume 3 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 356 f .

- ^ Norbert Zerlett: City of Bornheim in the foothills . Ed .: Rheinischer Verein für Denkmalpflege und Landschaftsschutz (= Rheinische Kunststätten . Volume 243 ). Society for book printing, Neuss 1981, ISBN 3-88094-349-4 , p. 19 .

- ^ Norbert Zerlett: City of Bornheim in the foothills . Ed .: Rheinischer Verein für Denkmalpflege und Landschaftsschutz (= Rheinische Kunststätten . Volume 243 ). Society for book printing, Neuss 1981, ISBN 3-88094-349-4 , p. 19 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 21st ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 21st ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 21st ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 34 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 21, 61 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 21st ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 21st ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 80 ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 29 ff .

- ↑ The village chronicle shows a b / w photo of the ceiling painting from the years 1908–1937

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 52 .

- ↑ according to Vorzepf's chronicle documented by the archives of the Archdiocese of Cologne : GVA Sechtem 8

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 36 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Castles and Courtyards, Graue Burg, section Patronage (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 49 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Castles and Courtyards, Graue Burg, section Patronage (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 255 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 138 ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 146 .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 138 ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 121 (Note 10 with reference to Josef Dietz).

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 120 ff .

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Church and School through the ages . 2001. (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 122-123 .