Albanian literature

The Albanian literature ( Albanian Letërsia shqiptare ) includes in Albanian language written works not only for Albania , but also from Kosovo , northern Macedonia , Montenegro and Serbia . The Arbëresh literature in Italy, written in their own dialect, and the literary works of Albanian diaspora and exile authors are also part of it.

Historical overview

Albanian literature in the strict sense of the word has been around since the 19th century. Before that, only a few authors wrote and published texts in Albanian. The oldest printed Albanian work is the missal by Gjon Buzuku from 1555. The late beginning of an independent Albanian literature finds its parallels with most of the other Balkan peoples who, like the Albanians, were under the rule of the Ottoman Empire for several centuries . In this state, Arabic , Ottoman and Turkish were the administrative and literary languages. In addition, Greek and Persian were widely used as written languages under the Ottomans . For the predominantly Muslim Albanians, the vernacular was also devoid of tradition in the religious sphere. The Christian minorities used Greek and Latin in worship . In Albanian there was only an oral tradition of fairy tales and folk poetry. Constantine and Doruntina are among the most famous folk legends .

The emergence of modern Albanian literature is closely linked to the efforts to create a uniform Albanian written language, which began in the mid-19th century and were part of the first phase of the Albanian national movement Rilindja . The focus of the Rilindja was initially on cultural and literary issues. In this respect, too, the Albanians developed like the other small peoples in Eastern Europe who were still under the rule of multinational empires.

Initially, literary production in Albanian was strongly influenced by the different cultural traditions of the regions in which the individual authors lived. Until the end of the 19th century, in addition to the writers from the Albanian settlement area in the Balkans, the Arbëresh , who had been living in Italy for a long time, played a major role. In Albania itself, the Gish literature of the north stands out from the Tuscan literature of the south, and religious differences (Muslim or Christian) were also formative until the middle of the 20th century. During the communist era, when contacts across borders were hardly possible, clear differences developed between literary work in Albania and Kosovo, which also reflected the different living conditions of the Albanians in both countries. In recent years, however, the literary scenes in Albania and Kosovo have visibly come closer. Today there is a book market covering the entire Albanian language area.

The history of Albanian literature can be divided into five periods:

- the early authors from the 16th to the 18th centuries,

- the time of the national movement in the 19th century,

- from independence in 1912 to the end of World War II in 1944,

- the period of communism 1944–1990,

- and contemporary literature since 1990.

The early writers

The historian Marin Barleti († 1513) from Shkodra stands at the beginning of the Albanian literary history . He wrote an extensive biography of Prince Skanderbeg ( Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum principis , Rome 1510) in Latin. Because of the subject matter and also the language that was understood by scholars everywhere, this work found readers across Europe. It was published again and again until the 18th century and translated into numerous European languages.

The first book in Albanian was a partial translation of the Catholic Missal , which the cleric Gjon Buzuku , who lived near Venice , made and had it printed in 1555. It took around four decades for the next Albanian publication to appear. In 1592 the Orthodox clergyman Lekë Matrënga († 1619) , who lived in Sicily, published the translation of a short Latin catechism under the title E mbsuame e krështerë . This is the oldest book in the Tuscan dialect. Pjetër Budi († 1622), the bishop of Sapa , had his translation of the then widespread catechism by Robert Bellarmin printed in 1621 . In the appendix he published his own verses on religious subjects. Budi also wrote a confession mirror , a handout for the Catholic Mass and translated the Roman ritual . Andrea Bogdani († 1683), who was the Catholic Archbishop of Skopje, belongs to the next generation . He wrote a Latin-Albanian grammar that has been lost but was used in his literary work by his nephew Pjetër Bogdani († 1689). The younger Bogdani was Bishop of Shkodra . His book Cuneus Prophetarum , published in 1686 and dealing with biblical subjects, is by far the most important prose text in early Albanian literary history. The book had two reprints up to 1702.

Giulio Variboba († 1788) belonged to the Arbëresh, the Albanian minority that had lived in Italy since the 15th century. In 1761 he had his poem Ghiella e Shën Mëriis Virghiër (The Life of the Virgin Mary) printed. This was the only book printed in the Italo-Albanian language in the 18th century. Nicola Chetta († 1803) was another Arbëresh author who also wrote in Albanian. The head of the Greek seminary in Palermo wrote verses on religious subjects in Albanian and Greek.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Islamic authors also appeared in public with poetic works in Albanian. In terms of form and content, their creations were in the tradition of Persian poetry, which was popular and respected in the Ottoman Empire at the time. The so-called Bejtexhinj literature was written in Arabic script. Well-known representatives of this style were Nezim Frakulla , Sulejman Naibi and Hasan Zyko Kamberi .

The literature of the Rilindja in the 19th century

In the 19th century, most of the peoples of Southeast Europe developed national movements, which always began with a cultural awakening. Small groups of educated men began to be interested in the traditional culture of their people and collected their testimonies. They created a modern written language, and more or less simultaneously the first works of the respective national literature were created. The first generation of national activists were influenced by Western and Central European cultural and political role models, because it was there that the nation emerged as a social ordering principle for the bourgeoisie and had already established itself in many countries.

Even for Southeastern European conditions, the first signs of a national movement among the Albanians appeared late, because the cultural and social conditions for it were extremely unfavorable. While the Greeks, Serbs and Bulgarians were religiously uniform and their Orthodox national churches were able to preserve and cultivate the cultural identity of these peoples during the long Ottoman rule, the Albanians were confessionally divided. The Muslim elites saw themselves as part of the Ottoman upper class, the Orthodox were led by Greek priests and the Catholics were often closer to their fellow believers in Italy or in the Habsburg Empire than to their Muslim neighbors. In addition, the political system of the Ottoman Empire granted the Orthodox churches certain rights of autonomy. For example, they could have books printed in their languages and run schools. Only in the course of the Tanzimat reforms did the Catholics also receive these opportunities. However , the government had no understanding for the independent cultural movements of the small Muslim peoples ( Bosnians and Albanians ). The publication of books in Albanian was forbidden again and again until the beginning of the 20th century, and mother-tongue schooling was also prohibited for Muslims in the Balkans. These are the reasons for the slow development of Albanian literature at that time.

The existential crisis of the Ottoman Empire became apparent for the Albanian elite in connection with the Russo-Turkish War 1877–1878 and the provisions of the Treaty of San Stefano . Now the Albanian settlement area was also affected by the disintegration of the empire. A political answer had to be found. The League of Prizren , founded by the Albanians , therefore demanded an autonomous Albanian vilayet within the empire in which the Albanian language should also be recognized. A number of authors who are now classics in Albanian literature were active in this political environment. They worked on creating a standardized written language, founded the first newspapers, published poems, wrote the first school books and founded the first cultural associations of their people. Over time, they also overcame denominational boundaries. The phase of cultural awakening in the second half of the 19th century is referred to in Albanian historiography as Rilindja (dt. Rebirth).

The biographies of some of the major Rilindja authors have important things in common: They worked in the Ottoman civil service, lived for a long time in the capital of Istanbul, and they were politically and journalistically involved in the Albanian cause. This applies e.g. B. for the two Frashëri brothers Naim and Sami as well as for Pashko Vasa and Kostandin Kristoforidhi . What they all have in common is a great patriotic enthusiasm and the resulting uncritical view of the actual cultural situation of the Albanian people at that time.

Kristoforidhi (1827–1895) published a memorandum for the Albanian language in 1857 , in which he justified the need for a uniform written language and thus gave the initial spark for efforts in this regard in the following decades. In literary terms, the Orthodox Christian made a name for himself as a Bible translator . The first complete translation of the New Testament and the Psalms into Albanian comes from him. Kristoforidhi worked out both a version in the Gegic and one in the Tuscan dialect, which he thus gave the same rank for literary production. His independent works are less literary and more practical in nature and didactic. In 1867 he was the head of a commission of writers who set the so-called Stamboller alphabet (a slight adaptation of the Latin script ) as the standard for printing Albanian books.

Naim Frashëri (1846–1900) was primarily a poet and is still a popular classic of Albanian literature to this day. He wrote epics in which he tried to lean on Virgil's style ( Bagëti e bujqësija ) or took up stylistic elements of Persian poetry ( Qerbelaja ). Like so many Albanian writers, he also left a work on the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg . Naim's brother Sami (1850–1904) excelled as a writer, especially in the Turkish language. He wrote the first Turkish novel, the first drama and the first encyclopedia in that language. For the Albanian culture he is primarily as a textbook author and author of the political writing Albania - what was it, what is it, what will it be. Thoughts and reflections on the dangers threatening our holy fatherland Albania and their averting of importance. His work as an organizer and editor is just as important. In 1879 Sami Frashëri was a co-founder of the Istanbul Society for the Printing of Albanian Literature , and as editor-in-chief he was in charge of the Albanian- language magazines "Drita" (1884) and "Dituria" (1885) in the capital.

Pashko Vasa (1825-1892) was primarily active in politics. As a writer, he mostly used the French language. In Albanian he wrote the well-known poem O moj Shqypni , which addresses the love of home and is still a kind of secret hymn of the Albanians today. Jani Vreto (1822–1900), who wrote some philosophical writings, also belonged to the Istanbul circle around Vasa and the Frashëri brothers .

Girolamo de Rada (1814–1903) worked in Italy around the same time as the authors of the Rilindja . His literary work was influenced by the intellectual currents of his Italian homeland, the political liberalism of the Risorgimento and romanticism in Italian literature . His works, written partly in the dialect of Arbëresh and partly in Italian, are part of the semi-mythical medieval Albanian history. The Canti di Milosao , the Canti storici albanesi di Serafina Thopia and Skënderbeu i pafat (German: The unfortunate Skanderbeg) are important. In 1848, de Rada founded the newspaper "L'Albanese d'Italia", a bilingual Italian-Albanian publication and the first newspaper ever to print articles in Albanian. Other Italian-Albanian authors of this era are Gavril Dara i Riu (1826–1885) and Giuseppe Serembe (1844–1901). They left behind some lyrical works that were only put into print after their death by Giuseppe Skiroi, among others . Skiroi (1865–1927) himself belongs to the next generation of Albanian-speaking authors in Italy. He wrote epics and poems and was a collector of Arbëresh folk songs. In contrast to the aforementioned Italian-Albanian authors, Skiroi also had close contacts with writers in Albania.

The second generation of modern Albanian writers includes men like Gjergj Fishta from Shkodra, Asdreni from Korca, Andon Zako Çajupi from the southern Albanian region of Zagoria and Faik Konica from Epirus . They went public with their first works around 1900 and then shaped literary life in the first two decades after Albania's independence in the country itself and in the diaspora. Asdreni belonged to the large Albanian exile community in Romania, as did Naum Veqilharxhi , author of the first Albanian primer ( Evetar , 1844). He wrote poetry on a wide range of subjects, headed the Albanian cultural association Dija and founded an Albanian-language elementary school in Constanța . The text of the Albanian national anthem comes from his pen . Çajupi lived as a merchant in Egypt. He created poetic works with a patriotic theme. Konica was first and foremost a diplomat, literary critic and promoter. In 1897 he founded the magazine "Albania" in Brussels. The magazine published articles in French and Albanian. On the one hand it offered western readers access to contemporary Albanian authors, on the other hand it provided Albanian intellectuals with information about cultural developments in the West.

The Franciscan Father Gjergj Fishta (1871–1940) introduced Albanian as the language of instruction at the Catholic grammar school in Shkodra in 1902 . In 1908 he co-founded the influential cultural association Bashkimi (Eng. Eintracht), in addition he was also active as an editor and publisher of two newspapers. In 1908 he represented Shkodra and the Catholic Church at the Congress of Monastir , which finally established the Latin alphabet as binding for the written Albanian language. This decision and the state independence of Albania proclaimed in 1912 also mark a certain turning point in Albanian literary history. The authors of the following decades stood linguistically on a solid foundation. This did not only apply to the spelling, rather Albanian was now also a recognized literary language, the use of which was self-evident and no longer had to be justified or justified. In addition, the circle of potential readers grew because an Albanian-language school system was slowly being built up. The occupying powers Austria-Hungary (in northern Albania) and France (in the south-east of the country) took the first steps in this direction during the First World War .

Interwar period

The new political situation after the First World War resulted in a significant expansion of the range of topics in Albanian literature. While the 1920s were still shaped by the traditions of the Rilindja, Albanian literature caught up with modern European developments in the decade before the Second World War . The absolute dominance of patriotic themes was broken, and the authors of the interwar period now increasingly turned to other subjects. In addition to poetry and epic, other literary genres also gained ground: the novella , the essay , theatrical literature . So published z. B. Gjergj Fishta with Anzat e Parnasit a small collection of satires in 1907 , the melodrama Shqiptari i qytetnuem in 1911 and his tragedy Judas Maccabeus in 1914 . Nonetheless, his most important work Lahuta e Malësisë ( Eng . The Lute of the Highlands) is an epic verse. An important influence for this work was probably the epic cycle songs of the border warriors compiled by Shtjefën Gjeçovi , which had previously only been passed down orally by bards.

Fan Noli (1882–1965) went down in the history of his country primarily as a co-founder of an independent Albanian Orthodox Church and as a politician. He was also active in literature and was, not least, an important translator. Noli translated the liturgical texts of Orthodoxy into Albanian, and he translated some of Shakespeare's plays . He also wrote a Skanderbeg novel, a drama The Israelites and the Philistines, and a study on the composer Ludwig van Beethoven . Most of Noli's literary work was created after the bishop went into exile in America in 1924.

Ibrahim Dalliu distinguished himself less as a poet and writer and more as a translator of the Koran .

Two young poets broke away from religious traditions in the interwar period and thus became part of modern European literature. These were Migjeni (1911-1938), who in his short life could only publish one volume of poetry ( Vargjet e lira , German free verse), and Lasgush Poradeci (1899-1987), from which the 1933 and 1937 volumes of poetry Vallja e yjve (Dance of the Stars) and Ylli i zemrës (Star of the Heart) appeared. Also the nihilistic novella Pse? (Why?), Published by Sterjo Spasse (1918–1989) in 1935, the short stories by Ernest Koliqi (1903–1975) , published in the same year, or the socially critical novella Sikur t'isha djalë (If I were a boy) by Haki Stërmilli (1895 –1953) are part of this awakening of Albanian literature into the modern age of the 20th century. Etëhem Haxhiademi (1902–1965) is worth mentioning as a playwright . He created tragedies that were not modern in terms of content and form, but were based on classical models, but were nevertheless of great linguistic beauty, and thus contributed much to the refinement of the Albanian literary language.

The years before World War II can be seen as the brief heyday of modern Albanian literature. Despite certain restrictions under the authoritarian Zogu regime, the intellectual life of Albania reached a remarkable climax. The literary development was not only carried by authors living in Albania, but also many authors living abroad were involved in the “turning to the Occident” or to Europe, which today is, however, experiencing a nostalgic transfiguration. In the prewar period, many intellectuals considered fascism or communism to be promising prospects for the regeneration of European culture. There was a lively exchange between the communities in exile in Romania, Italy, the USA and the mother country. The Kosovar Albanians were hardly involved , as there were hardly any publication opportunities for them in Yugoslavia in the interwar period.

Musine Kokalari (1917–1983), who published her first collection of fairy tales in 1941, is considered to be the first woman in Albania to work as a writer and to publish a book.

1945 to 1990

Through the Second World War and above all through the establishment of the communist dictatorship in Albania, there was a total break in Albanian literature with pre-war traditions. The new rulers, led by Enver Hoxha, branded many members of the non-communist intellectual elite as fascists, and the persecution began shortly after the end of the war. The methods used by the communists ranged from publication bans to prison and the death penalty. In fact, quite a few writers such as B. Vangjel Koça, Ismet Toto and Vasil Alarupit, whose works are still received quite uncritically and repeatedly printed, who support fascist ideology or other authoritarian concepts of society on a Kemalist or clerical basis. Others, while collaborating with the occupiers to some extent to make a living, were by no means advocates of fascism. Many important Albanian intellectuals such as Ernest Koliqi , Midhat Frashëri and Tajar Zavalani fled abroad. The first wave of persecution immediately after the war fell victim to the Catholic authors Ndre Zadeja, Lazër Shantoja, Bernardin Palaj and Anton Harapi . In 1945 you were sentenced to death in show trials as "clerical fascists" and executed. In 1947 the communists executed the Bektashi author Baba Ali Tomori . In 1951 the priest and writer Ndoc Nikaj and the poet Manush Peshkëpia suffered the same fate. The playwright Etëhem Haxhiademi died in 1965 after a long imprisonment. More or less a generation of writers has been wiped out or driven out of the country. Her works were banned until the end of communism in 1990.

As a result of the persecution of the communists, the literary life of Albania came to a standstill for more than a decade. It was not until the early 1960s that books were written and published on a large scale again. The little that was previously published had to conform to the Stalinist cultural policy adopted by the Soviet Union . Thematically, the glorification of the partisan struggle under the leadership of the Communist Party was absolutely in the foreground. In the 1950s several hundred students were studying in the Soviet Union and other socialist countries; among them were linguists and literary scholars. After the political break with the Soviet Union (1961), these shaped literature in the style of socialist realism .

The literacy of the rural population, which was successfully pursued by the communists, increased the number of potential readers many times over in the 1950s and 1960s. Only since then had books, newspapers and magazines actually become mass media in the sense of the word in Albania. At the same time, Albanology got its own scientific institutes through the establishment of the University of Tirana and the Albanian Academy of Sciences . Through this institutionalization of Albanian philology, linguistic and literary studies separated more and more from literary production. Not only in the era of Rilindija, but also in the interwar period, it was above all the writers who were also active in linguistics, who promoted the standardization of the written language and wrote school books and grammars.

Since the 1960s, despite the restrictions imposed by the dictatorship, the generation of younger authors who had to come to terms with the rulers for publication increased. The literary magazine "Drita" (dt. Light), published weekly since 1961 and published by the Writers' Union, was the most important medium in which new authors were introduced to the Albanian public. The choice of subjects and forms of expression was always a tightrope walk for the writers, because the communist censors judged erratically and arbitrarily. Despite this, many works of lasting value were created, especially in the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1961, Ismail Kadare and Dritëro Agolli , who belonged to the new generation of writers, published their first large collections of poetry. Both had studied in the Soviet Union. In the following years you rose into the socialist establishment, were members of parliament and Agolli became chairman of the writers' association in 1973.

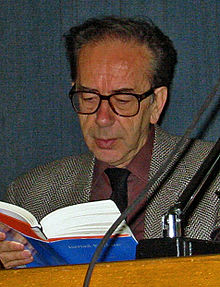

Kadare soon turned to prose and wrote numerous novels in the decades that followed. Since the 1970s, he has been the most influential writer in his country. He was the only one to be known and appreciated abroad. His books have been translated into numerous European languages. Kadare's fame and popularity made it possible for him to reflect on the social conditions in Albania in his works - albeit in clauses - and also to criticize them to a certain extent. In this respect, his work was almost unique; other authors were jailed for less clear words. On the part of the Albanian exiles, Kadare was criticized as a political opportunist who bought his relative freedom by being close to the dictator Enver Hoxha. Before the anti-communist revolution, Kadare went into French exile for a few years in 1990. Even today he is a prolific writer who is widely recognized in Albania.

Dritëro Agolli, who headed the Writers' Union in 1973 after a wave of political purges, began his career with two volumes of poetry and some regime-compliant novellas about the partisan struggle. He was particularly valued by readers for his satire Shkëlqimi dhe rënia e shokut Zylo , a criticism of the socialist bureaucracy. Agolli was also able to continue his career after 1990.

Sabri Godo from Delvina in southern Albania was best known as the author of historical novels. Neshat Tozaj from Vlora caused a sensation in 1989 with his novella Thikat (The Knives), in which he criticized the apparatus of repression of the secret police Sigurimi . Fatos Kongoli from Elbasan worked at times as a culture editor during the communist era. Before the fall of the Wall, he was able to publish some short stories and the novel Ne të tre (We three). Kongoli only had its big breakthrough after 1990; Today he is one of the most popular and productive storytellers in the Albanian language. It is also published and read abroad. His successful novel The Albanian Bride , published in German translation in 1999, takes place in the Albania of political cleansing.

It is noteworthy that most of the well-known authors of the socialist period come from southern Albania, i.e. the Tuscan-speaking area. In addition to those already mentioned, this also applies to Naum Prifti , Teodor Laço, Kiço Blushi and Sulejman Mato . This has to do with the fact that the Tosken dominated the communist elite and the persecution hit the writers from the formerly bourgeois Shkodra, the cultural center of the north, particularly hard.

Since 1990

After the fall of the Wall, authors who were disadvantaged by the communist system could also publish their works or become active as a journalist. These include Fatos Lubonja, known as a dissident, and the poet Visar Zhiti , who was also imprisoned and later became Minister of Culture and Diplomat. Both secretly wrote works while in detention. The poet Ferdinand Laholli , who lives in Germany, was also not allowed to publish books in communist Albania. Like Ornela Vorpsi, who wrote in Italian, or the novelist Thanas Jorgji , who also lives in Germany , he emigrated shortly after the fall of the Wall. Elvira Dones , who writes in Italian and Albanian , had fled the country earlier. In addition, numerous other older and younger authors such as Luljeta Lleshanaku also use the opportunity to freely write and publish.

Mimoza Ahmeti is one of the most famous contemporary Albanian poets . The poet Ledia Dushi has been heavily criticized for writing works in the Gian dialect of her hometown Shkodra. Today several authors write in Gegisch without encountering significant criticism.

Modern Albanian Literature in Kosovo

The poet Esad Mekuli (1916–1993) was at the beginning of Albanian literature in Kosovo . The veterinarian trained in Belgrade wrote socially critical poems and founded the literary magazine "Jeta e re" (New Life) in 1949, of which he was editor-in-chief until 1971. During these two decades, “Jeta e re” was almost the only publication option for Albanian authors in Yugoslavia, because printing permits for books in Albanian were rarely given. One of the first Kosovar prose authors was Hivzi Sulejmani (1912–1975), who was able to publish his first volume in 1959 in Pristina . His novel Fëmijët e lumit tim (The Children of My River) from 1969 is one of the very well-known books of that time in Kosovo. This also applies to the novel Gjarpijt e gjakut (The Serpents of Blood) by Adem Demaçi , printed in 1958 , who had to spend 28 years as a political prisoner in Yugoslav prisons. In his famous work Demaçi deals with the social consequences of blood revenge.

With the beginning of Tito's new Kosovo policy in the 1960s, which culminated in the autonomy of the province in 1974, Albanian literature in Kosovo also had much better opportunities to develop. It was significant that Albanian became the school language and the literature of the Albanians. Thus the circle of potential readers expanded many times over within a few years. At the same time, a young intellectual elite formed at the University of Pristina, from which many Albanian writers who are still active today emerged. The 1970s were the heyday of Albanian literature in Kosovo. The ideological pressure at that time was much lower in Yugoslavia than in Albania. As far as the linguistic training of young authors is concerned, Pristina could not compete with Tirana. An exchange between the two Albanian literary centers was impossible because of the closed borders. The career of the writer and eminent literary critic Rexhep Qosja began in the 1970s . In 1974, the then head of the Albanological Institute of the University of Pristina published his successful novel Vdekja më vjen prej syve të tillë (Death lies in such eyes). To this day (2013) Qosja is a central figure in the literary life of Kosovo. Other authors who have shaped Kosovar literature in the last three decades of the 20th century are Ramiz Kelmendi, Azem Shkreli (1938–1997), Nazmi Rrahmani, Luan Starova , Teki Dërvishi, Musa Ramadani, the German translated Arif Demolli ( 1949–2017) and Beqir Musliu (1945–1996).

Modern Albanian Authors in the Diaspora and in Exile

After the Second World War, Arbëresh literature no longer played such a major role in the Albanian context. On the one hand, literary production in Albania and later also in Kosovo grew strongly; on the other hand, the number of Albanian speakers and writers in Italy continued to decline due to assimilation. Nonetheless, Arbëresh also made contributions to Albanian literature in the post-war period. An example is the priest Domenico Bellizzi (1918–1989) from Calabria, who published poems under the pseudonym Vorea Ujko. Edited volumes of his poetic works were also printed in Albania and Kosovo.

Arshi Pipa and Martin Camaj are mentioned as important exiled authors of the second half of the 20th century . Pipa had lived in the USA since 1957, where he directed the Albanian cultural association Vatra and published numerous works in his mother tongue. Camaj was professor for Albanian linguistics and literature in Munich. He wrote novels, short stories and poems himself.

The Montenegro- born Kaplan Burović (* 1934) emigrated to Albania in the 1960s and now lives in Geneva .

See also

literature

- Ali Aliu : Letërsia bashkëkohore shqiptare. Pas Luftës së Dytë Botërore . Tirana 2001, ISBN 99927-700-3-1 .

- Robert Elsie : Albanian Literature. A short history . IB Tauris, London 2005, ISBN 1-84511-031-5 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Robert Elsie: Albanian Literature. An Overview of its History and Development . In: Österreichische Osthefte . Special Volume Albania, No. 17 . Vienna 2003, p. 243–276 ( elsie.de [PDF; 208 kB ; accessed on May 6, 2015]).

- Sabri Hamiti: Letërsia modern shqiptare. Gjysma e parë e shek XX . Tirana 2000, ISBN 99927-700-0-7 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Thomas Kacza: Patriotism and Politics - Fourteen literary voices for Albania . Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2017, ISBN 978-3-8300-9770-9 .

- Bajram Kosumi : Letërsia nga burgu. Kapitull më vete në letërsinë shqipe . Botimet Toena, Tirana 2006, ISBN 99943-1-187-5 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Rexhep Qosja : Prej letërsisë romantike deri te letërsia modern. Shkrimtarë dhe periudha . Pristina 2006.

- Joachim Röhm : Albanian literature of post-communism . In: Lichtungen - magazine for literature, art and criticism of the times . No. 103 . Graz 2005 ( Foreword [PDF; 19 kB ; accessed on May 6, 2015]).

- places. Swiss literary magazine . Poetry from Albania, No. 189 , 2016, ISBN 978-3-85830-183-3 .

- German-Albanian Friendship Society (Ed.): Albanische Hefte . No. 3 + 4 , 2018, ISSN 0930-1437 (focus on poetry with articles on poetry in the interwar period, socialist realism, contemporary poetry and various author portraits).

Web links

- Robert Elsie: Albanian Literature in Translation . (English)

- Gjuhashqipe.com: Letërsia . (Albanian)

- Small selection of books from and about Albania . In: Pearl Divers

Individual evidence

- ↑ Miroslav Hroch : The champions of the national movement among the small peoples of Europe . In: Acta Universitatis Carolinae. Philosophica et historica. Monographia 24 . Prague 1968.

- ↑ Rezarta Delisula: Tirana-Mahnia . Maluka, Tirana 2018, ISBN 978-9928-26018-5 , Tiranasi që prktheu Kuranin, p. 104 f . (Reprinted from an article published in Gazeta Shqiptare (p. 15) on April 21, 2002.).

- ^ Enis Sulstarova: In the Mirror of Occident: The Idea of Europe in the Interwar Albanian Intellectual Discourses . In: Metropolis . No. 6 , 2008, p. 687-701 .

- ^ Robert Elsie : Historical Dictionary of Albania . In: Historical dictionaries of Europe . No. 75 . Rowman & Littlefield, 2010, keyword Kokalari, Musine , p. 232 f .

- ^ Cyrill Steiger: Poetry from Albania. A fascinating world of poetry . In: places. Swiss literary magazine . Poetry from Albania, No. 189 , 2016, ISBN 978-3-85830-183-3 , pp. 9 .