Bag passage

The bag transition or bag work is a vision machine . They separated in a craft union flour mill by means of a sieve to be ground endosperm from the bran .

The views and Seven are actually for different procedures . In grain milling, the two can not be clearly delineated technologically and historically . Therefore mill lore uses the two terms synonymously .

history

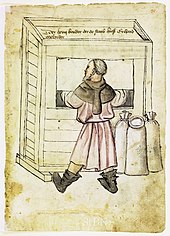

After 800, the riddling bag spread . The bag gear mechanized it, using the same drive energy as the grinding gear - wind , water or animal muscle power , moved the work step to the grain mill . Its invention was probably made in the 15th century. Leonardo da Vinci recorded it in his sketchbook , which was used from 1493 to 1502 . The first verifiable uses came from cities in the Holy Roman Empire : "In the year 1502 Wednesday for Joh. Baptistae the wheelwork of the bags in mills all here in Zwickau was first developed and used." In 1533 a master from Memmingen taught the Appenzellern the beautiful white bag to prepare flour . The 16th century saw the technology slowly spread.

From the last quarter of the 16th century, the young technical science dealt regularly with the bag walk. Augustin di Ramelli published a brief explanation of a mill with a bag-feed in Treasury of Mechanical Arts (Paris 1588 and Leipzig 1620). The accompanying drawing gave the latter indistinctly. Fausto Veranzio described and drew a complete pouch passage in Machinae novae (Florence / Venice 1615/1616). He pointed out that the type mentioned was the one common in Germany . Jacobus de Strada made numerous drawings of water systems around 1580, including a water mill with an overshot water wheel , grinding and bag passage. His grandson published it in Machine (Frankfurt am Main 1617). The 2nd edition under the title Künstlerischer Abriss allerhandt Wasserkünste (Frankfurt am Main 1629) contained a more detailed explanation. De Strada's drawing achieved greater fame through copying by Georg Andreas Böckler in Theatrum machinarum novum, which is the newly increased arena of the mechanical arts (Nuremberg / Frankfurt am Main 1661).

Generalizing statements such as the bag walk "... became common in the 17th century" did not stand up to closer examination. The cause was two major disadvantages of the bag. 1) Due to the multiple dumping and sifting , the processing volume of a grain mill decreased. Freiberg experienced a major drought and a corresponding water shortage in 1580 . After removing the vibrating bags from the water mills, they ground twice as much grain every day . 2) Separating the bran reduces the amount of final product that can be baked into bread . The above-mentioned Electoral Saxon city further to the west forced the hardship of the Thirty Years' War to abolish the bag walks in 1641. In this context it was mentioned that the technology was not used in many places.

The city council of Göttingen decided in 1735 to modernize its large mill in order to expand a bag passage. The system stopped working after less than two years. Müller Sievert could not deal with it and, due to the lack of low demand, had no interest in continuing. His successor, Ohms, said in 1750: “Nobody would have wanted to grind on it because it would lose a noticeable amount of flour, and it wasn't necessary to bring out as much flour as on the ordinary mills.” In 1797, a survey was conducted in several Prussian parts of the country to improve the milling system . The War and Domain Chamber in Minden received the following answer from the county of Mark : “The mills do not go into trouble, and so much is known here, not a single mill has been set up in this area. The bagging is done by the consumers using a hand bag mill . ”The same situation certainly applied to other parts of the country, especially rural regions. The passage of time brought several developments (more powerful bag stuff ; Length of flour box ; rolling bag ; inclination, length and fabric of Rüttelbeutels; increased shaking).

More effective sifting machines , first the sifting cylinder invented in 1785 by the English engineer John Smeaton , replaced the bag aisle . Around 1900 it still contained a few, small mills. Although it continued to work on its optimization. In 1957, the Swiss Federal Office for Intellectual Property awarded the Austrian Franz Zins with patent no. 317434 for a "mill for small businesses with a new and better bag device". According to the inventor, an additional support resulted in a horizontal and vertical movement of the vibrating bag at the same time, thus enabling a finer view. A usage has not been reported. The German Museum of Technology in Berlin ( Bohnsdorf post mill moved there in 1983 ) and the Cloppenburg museum village ( Bokel cap windmill moved there from 1939–1941 ) , for example, make it possible to visit a bag passage .

technology

The bag passage connects directly below the grinding passage because this is where the drive takes place. It consists of 1) the bag-finished as the transmission machine, 2) the Rüttelbeutel as a working machine , 3) the powder box as the surrounding housing , and 4) a mostly removable bran box (also Before box ). 5) Later the Sauber was added as a downstream machine. The preparation of the overall machine took millwright .

Bag stuff

The bag stuff (also visible stuff) transfers the energy from the mill iron to the vibrating or rolling bag . There are four types of it:

- The fork causes a back and forth movement. Two pillars of bags tower up behind the flour bin . This connects a bag bridge at the bottom and a bar at the top . In between there is the vertical, wooden vibrating shaft supported on both sides in track pegs . Two or three wooden stakes (thumbs) are attached to the mill iron, usually on the underside of the lantern . With each revolution of the runner block, they hit the stop (arm) on the back of the vibrating shaft and trigger a partial revolution. Later, the three-stroke (three cams on the lantern) was used.

- The lever should always rest firmly on the three-stroke stroke. A spring rod made of elastic ash wood is used for this . The branch is guided by a movable bracket in the floor over a fixed counter- bearing and, through its tension, presses the counter-holder and ultimately the stop. The bracket can be moved with a rope and so the tension can be changed.

- An elastic, wooden vice is used to pull back the vibrating shaft. A rope connects him to another arm. This proposal is slightly shorter than the stop and is attached below it. On the opposite side there is a fork (also known as a vibrating stick or shaking stick). If possible, it consists of wood that is grown and therefore stronger. The two ends are in the ears of the riddle bag. To protect the material, they are shod with light, iron tills.

- The large hoist moves up and down. At the back of the flour pan is the pillar with two large pegs . The vertical setting shaft rotates between the two. A proposal and proposal are attached to this. A little above that, between the hanging blocks, lies the horizontal, longer, arm-provided viewing wave (also bag, wheel or wheel wave). The vibrating bag hangs on its two sight arms (also wheel arms). Outside the flour pan sits another short arm on the viewing column. One end of the wheel rail (also called Radeschinne) rotates in a slot (wheel head, wheel or wheel scissors). The wheel nails connect them. At the other end, the proposal of the setting wave exerts pressure. A ball joint can be used to transfer the shaking movement from the setting shaft to the viewing shaft.

- The fabric tension can be changed from the outside through holes of different sizes in the wheel head and rail. The weight of the vibrating bag is usually sufficient to pull back the stop on the pegs of the lantern. If necessary, there are two options for increasing the performance of the bag movement. This is made possible by a vice attached to the viewing shaft, including rope and wheel, or a flexible trunk rod for resiliently pressing down the wheel head.

- A setting shaft belongs to the small hoist like the vibrating shaft in the fork. It stands on a footbridge between two viewing pillars. The flour box takes on a smaller visual wave with the wheel head and the arms for the vibrating bag.

- In addition to the shaking movement, the roller bag sets the roller bag in a rotating movement. The waiver of the three-stroke reduces noise pollution .

The effectiveness increases from the fork to the hoist to the roller. In addition, the shaking movements per millstone revolution were increased to two or three in later times .

Riddling bag

The vibrating bag (also known as a whip, swing or sieve bag) has a hose- like shape and hangs at an angle in the flour pan . The recesses of its inlet and outlet match those at the ends of the fabric bag. The cross-section is given by round, oval or trough-shaped iron rings. They are sewn into double, strong canvas . The lower cap has eyes so that the necessary fabric tension can be achieved using rope and a small winch . This has a decisive influence on the efficiency . From the 19th century, she made a spring .

Before processing , the ground material is fed from the grinding to the bag aisle. It turns out the Mahlloch of the former through the slide flour ( wood overflow pipe ) in the upper opening of Rüttelbeutels. This must be shaken in order to achieve the sieve effect. For this purpose, leather ears (handles) sewn on above the middle of the hose absorb the movement of the bag . While the flour from screened is that slips bran through the lower opening out into the bran box or previously in the Sauber .

The American engineer Oliver Evans invented the roll-up bag after 1785. He began developing the successor technology - the sight cylinder . It is driven by the roller . The bag cloth covers a cylinder woven from wire . This increases its durability. The rotary movement enables the entire tissue area to be used. The roll-up bag was hardly ever used in Germany .

In the beginning, the vibrating bags consisted exclusively of woolen gauze made for this purpose . It wore out in about three months. England was a leader in the manufacture of linen pouches . The cloth coming from there was stiffer, smoother, more durable and let the flour through better. It was not until the 19th century that German weaving mills , especially in the Kingdom of Saxony, began producing competitive products. From 1780 artificial silk was also used, which came from Lyon and Reims in France or Switzerland . Weavers who specialize in bag hoses were based in Thuringia - in Eisenberg , Münchenbernsdorf and Schwarzhausen . Regardless of the fabric , each mill had several copies available. Their different mesh densities were based on the types of grain . They could be tighter when using a cleaner. This made it possible to produce even finer flour. The pure crushing the shot tube replaces the Rüttelbeutel.

Flour box

The flour box (also bag or viewing box) stands on four feet like a piece of furniture . The inlet is fixed, the height of the outlet is variable. The latter allows a change in the perspective effect of the suspended there Rüttelbeutels . To do this, the Schroff is located on the front wall. The board with an opening to hold the bag cap can be moved between two strips . The flour trickling into the box can be removed by hand. The opening, which is preferably recessed on the right, is intended for this. During operation, it drapes a cloth or closes it with a slider. The former also applies to the rear opening through which the fork is passed.

The production of the solid wooden box was apparently done by mill builders or carpenters . During the baroque period it was often decorated with rich carvings , including a miller's coat of arms . Across the ages, the spout was mostly decorated with a handcrafted , colorfully painted, grimaceous mask - the bran puke .

Clean

The Sauber separates the peel remains from the bran . In this way, they don't have to be piled up again and again. Its base consists of two types of fine flat seven made of wire . The vibrating movement is carried out by means of a linkage that drives the three- stroke impact on the mill iron .

Linguistics

The verb pouch stands in the figurative sense for 'in dire straits, great difficulties, have been afflicted by many blows of fate'. The meaning arose from the rhythmic hitting of the vibrating bag , which literally whipped the flour through the fabric .

The rattle of the mill that was sung about was ultimately a deafening noise . It was caused by the triple blows of the bag and grinding aisle .

literature

- alphabetically ascending

- Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler , Otfried Wagenbreth : Mills. History of the flour mills. Technical monuments in Central and Eastern Germany . 1st edition, German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig / Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 .

- Micaela Haas, Joachim Varchmin: Mills yesterday and tomorrow. Wind and water power in Berlin and Brandenburg . Martina Galunder Verlag, Nümbrecht 2002, ISBN 3-89909-009-8 .

- Heinrich Herzberg (author), Hans Joachim Rieseberg (collaboration): Mühlen and Müller in Berlin . Partial edition, Werner-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1987, ISBN 3-8041-1977-8 .

- Wolfgang Kuhlmann: water, wind and muscle power. The flour mill in legends and facts . Ed .: German Society for Milling Customers and Mill Maintenance . Petershagen-Frille 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037659-7 .

- Johannes Mager , Günter Meißner, Wolfgang Orf: The cultural history of the mills . Edition Leipzig, Leipzig 1988. ISBN 978-3-361-00208-1 .

- Werner Schnelle (author), Rüdiger Hagen (editing): Mill construction. Preserve and preserve water wheels and windmills . Ed .: German Institute for Standardization . 2nd, revised edition, Beuth Verlag, Berlin / Vienna / Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-410-21342-0 .

Web links

- Klostermühle Heiligenrode - Video of the bag walk

annotation

- ↑ The Wikipedia article, which is specifically related to transmission machine , unfortunately restricts the term to historical belt drives . (Compare to: Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: Mühlen. History of the grain mills . German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , 1 The mechanical development of the grain mills. [Introduction], S. 7.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Heinrich Herzberg, Hans Joachim Rieseberg: Mühlen and Müller in Berlin . Partial edition, Werner-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1987, ISBN 3-8041-1977-8 , 2 mills and mills. Flour and barley mills, pp. 26–32, here pp. 29–31.

- ↑ a b Werner Schnelle, Rüdiger Hagen: Mill construction . 2nd edition, Beuth Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-410-21342-0 , 4 Construction of traditional processing machines for wind and water mills. 4.3 Classifying machines. On the development of the classifier, p. 130.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: Mühlen. History of the flour mills . 1st edition, German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , 1 The mechanical development of the grain mills. 1.1 Grinding units, sieving machines and other working machines of the grain mills. Sieving (sifting) the grist, pp. 21–24.

- ↑ a b Micaela Haas, Joachim Varchmin: Mills yesterday and tomorrow . Martina Galunder Verlag, Nümbrecht 2002, ISBN 3-89909-009-8 , 2. The traditional wind and water mills. 2.3. The technology of the artisanal mill. [Introduction], pp. 15–17, here pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: mills. History of the flour mills . 1st edition, Deutscher Verlag für Grundstofftindustrie, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , attached pictures. The sieving (sifting) of the flour from the 16th to the 19th century. Fig. 7, p. 300.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Wolfgang Kuhlmann: Water, wind and muscle power . German Society for Mill Knowledge and Mill Conservation, Petershagen-Frille 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037659-7 , 12. A woman makes the start. From the oldest technical mill drawings, pp. 81–87, here pp. 83–86.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Johannes Mager, Günter Meißner, Wolfgang Orf: The cultural history of the mills . Edition Leipzig, Leipzig 1988. ISBN 978-3-361-00208-1 , Der Weg der Mühlentechnologie. From grinding and bag mills to roller mills and plansifter, pp. 28–41, here pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: mills. History of the flour mills . 1st edition, German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , 6 mills in technical sciences. 6.1 Mills and Machine Science, pp. 146–148.

- ↑ Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: mills. History of the flour mills . 1st edition, German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , list of sources and further literature. References to section 6.1. Original literature on machine science with mills up to 1800, p. 402.

- ↑ a b Ilka Göbel: The mills in the city. Miller's trade in Göttingen, Hameln and Hildesheim from the Middle Ages to the 18th century . Dissertation University of Göttingen 1991 (= publications of the Institute for Historical Research at the University of Göttingen . Volume 31). Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld 1993, ISBN 3-927085-87-1 , 4.4.2.2 Introduction of New Milling Techniques, pp. 96-99.

- ↑ Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: mills. History of the flour mills . 1st edition, German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , directory of persons. Smeaton, John, p. 426.

- ↑ Micaela Haas, Joachim Varchmin: Mills yesterday and tomorrow . Martina Galunder Verlag, Nümbrecht 2002, ISBN 3-89909-009-8 , 7. Brief descriptions of a selection of wind and water mills. 7.1. The mills in Berlin. The post mill in the German Museum of Technology Berlin, pp. 107–111, 1983: p. 108; Bag sifter: p. 111.

- ↑ Cap windmill from Bokel . In: Foundation Museumsdorf Cloppenburg (Hrsg.): Museumsdorf Cloppenburg (accessed on June 19, 2019).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Werner Schnelle, Rüdiger Hagen: Mill construction . 2nd edition, Beuth Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-410-21342-0 , 4 Construction of traditional processing machines for wind and water mills. 4.3 Classifying machines. Beutelgang, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: mills. History of the flour mills . German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , 1 The mechanical development of the grain mills. [Introduction], p. 7.

- ↑ Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: mills. History of the flour mills . 1st edition, German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , directory of persons. Evans, Oliver, p. 419.

- ↑ Renate Wahrig-Burfeind (Ed.): Wahrig German Dictionary. With a lexicon of language teaching . 8th, completely revised and updated edition, Wissenmedia Verlag, Gütersloh / Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-577-10241-4 , beuteln, p. 266, column 2.

- ↑ Helmut Düntzsch, Rudolf Tschiersch, Eberhard Wächtler, Otfried Wagenbreth: mills. History of the flour mills . 1st edition, Deutscher Verlag für Grundstofftindustrie, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-342-00672-2 , attached pictures. The sieving (sifting) of the flour from the 16th to the 19th century. Fig. 8, p. 300.