German exile during the Nazi era

German exile during the Nazi era began in 1933.

Exiles

Due to the National Socialist persecution policy, political opponents of the National Socialists in particular initially decided to leave the German Reich .

In the period that followed, primarily disenfranchised people of the Jewish faith gave up their German homes. The law to restore the civil service , the Nuremberg Laws and the November pogroms of 1938 formed the background for the decision.

Hundreds of thousands of those who were persecuted or disenfranchised left the German Reich . According to estimates, there were 500,000 people who walked this route during the Nazi era . 360,000 of the exiles came from Germany. After the annexation of Austria in 1938, around 140,000 Austrians were added.

The vast majority of them, between eighty and ninety percent, were of Jewish descent.

With the step into exile, the people tried to avoid imprisonment, deportation to a concentration camp and killing. The fate of Anne Frank shows that this could happen anyway .

On October 23, 1941, the Reich Main Security Office under Heinrich Himmler issued a general travel ban for Jews.

Previously, the National Socialist leadership, namely Hermann Göring , had tried to speed up the emigration of Germans of Jewish origin by setting up the Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration in early 1939 . The Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Vienna , established in 1938, served as a model for the Reich headquarters . At the beginning of its activity, the Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration tried to bring about the emigration of people. During the Second World War it organized deportation to the extermination camps .

writer

German writers were prohibited from publishing who did not agree with the views of the National Socialists. In May 1933, many of them learned that their works had been burned . In order to survive, they decided to go into exile.

There were also expatriations of outlawed writers in Germany . Kurt Tucholsky was one of the expatriates .

Exile literature

In 1933 was in Amsterdam the Querido Verlag . This published literature created by German authors during the period of exile .

The literary scholar Walter Arthur Berendsohn is considered the founder of German exile literature research . Berendsohn had to leave Germany himself in 1933 because of his Jewish descent.

Exile as a topic in German-language literature

Klaus Mann was one of the authors who, as exiles, made exile the subject of their writings . His novel Der Vulkan describes the situation of German exiles in Paris and elsewhere.

The fate of the exiles in Marseille and their often humiliating battle for Visa formed the background of the novel Transit of Anna Seghers , who appeared 1944th

Judith Kerr published the book When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit in 1971 . This describes the flight of her Jewish family from National Socialist Germany.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Ursula Krechel focused on exile and the people affected by it in two novels. In the novel Shanghai Far From Where , she describes the fate of some of the 18,000 Jews who were able to survive in the Shanghai ghetto . Krechel's novel Landgericht , for which she received the German Book Prize in 2012 , presents the Jewish judge Dr. The focus is on Richard Kornitzer, who finds exile in Havana and returns to his family from exile in Germany in 1947, where he fails with his desire to make amends and restore his dignity.

Publicists

Hundreds of magazines appeared outside of Germany between 1933 and 1945, which were edited by exiles. Their publication duration rarely exceeded a year. An example of one of the magazines is the Free Press , which publicists published.

Filmmakers, directors, screenwriters, actors, cameramen, technicians and editors

An estimated 2,000 filmmakers, directors , screenwriters , actors , cameramen , technicians and editors left the German Reich.

While other European countries were initially an important refuge for them, the United States of America became increasingly important in this respect after the start of the war.

Billy Wilder, for example, moved to Paris in 1933 and was able to travel to the United States a year later.

Many established a new artistic existence in the host country .

However, exiles who fled to the Soviet Union were also among those who fell victim to the Stalinist purges . This applied to the employees of the Meschrabpom film production company .

scientist

The German universities lost around 19% of their teaching staff between 1933 and 1945 due to the National Socialist takeover. Most of them were Jews or scientists of Jewish origin. As recent research shows, around 62% of those discharged emigrated. The Emergency Association of German Scientists Abroad was founded in 1933 to support them . This aid organization found new jobs for scientists in exile. This did not necessarily mean a possibility to continue one's own scientific work.

Some German scientists were able to advance their scientific careers in exile. This was true for Max Born .

Max Horkheimer and the Institute for Social Research (IfS) managed to prepare for emigration in good time and to relocate the institute first to Geneva and later to the USA. Due to the funds available to the institute even in exile, it was not only able to continue its own research work, but also to provide financial support to emigrated social scientists.

How difficult it was to emigrate and survive can be seen in the résumés of Ernst Abrahamsohn and Ernst Moritz Manasse . Not only did they grapple with the adversities of US immigration policy, but they also found jobs that fell short of original hopes. Manasse, for example, who had become a refugee because of his Jewish origins, became a lecturer at an institution that was marginalized on racial grounds, a university in Durham that was only accessible to blacks . He was the first fully employed white teacher at the institution.

Teachers and educators

More than 20 schools in exile were founded worldwide by teachers and educators who had to leave Germany after 1933. These also offered jobs for exiles and thus ensured survival.

One institution whose background was the Popular Front strategy was the Free German University in Paris.

Architects

The law to restore the civil service of April 1933 caused many architects to lose their offices in administrative positions. Freelance architects and urban planners who were of Jewish origin, politically unpopular, or both were forced out of their professional association, the Bund Deutscher Architekten (BDA), and not accepted into the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts , which in fact amounted to a professional ban. This is what happened to Ferdinand Kramer , who emigrated to the USA. After the war, Max Horkheimer brought him back to Frankfurt, where from 1952 to 1964 he was the building director of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University .

The Bauhaus architects Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe were also sold .

Many well-known architects found refuge in Turkey , including Bruno Taut , Robert Vorhoelzer , Wilhelm Schütte and his wife Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky , the inventor of the Frankfurt kitchen .

Ernst May , the father of New Frankfurt , had accepted an invitation to the Soviet Union in 1930 with a group of his colleagues. When his ideas about town planning could not be realized there, he could no longer return to Germany because the National Socialists had meanwhile gained power. He first emigrated to Tanganyika in East Africa and bought a farm there. From 1937 he returned to architectural projects. He opened an office in the Kenyan capital Nairobi . The British interned him in 1939 . May was suspected of being an anti-Semite and of having worked as a spy for the National Socialists in the Soviet Union. From 1940 to 1942 he was in custody in the Union of South Africa on suspicion .

Receiving countries

While other European countries were initially chosen as the place of exile, politically persecuted people, Jews and others fled to non-European countries at the beginning of the Second World War and the associated occupation of neighboring countries by German troops .

Less than 10,000 persecuted and disenfranchised Germans were admitted to Scandinavia , Denmark , Norway and Sweden . Denmark played an important role as a transit country . Tens of thousands made their way to third countries from there.

Several hundred were accepted into Turkey between 1933 and 1945 .

South America , for example Bolivia and Uruguay , took in significantly more people who were persecuted and disenfranchised than Scandinavia, although they also traveled on to the United States (around 130,000 exiles) after being there.

The St. Raphaels Association in Hamburg provided support in escaping to South America, mainly to Brazil .

An estimated 55,000 people fled to Palestine .

The first centers of German exiles emerged in Czechoslovakia (approx. 9,000 exiles), in France (approx. 100,000 exiles), the Netherlands (approx. 10,000 exiles) and Switzerland (approx. 25,000 exiles).

Entry requirements

Strict entry regulations made it difficult for those wishing to leave Germany.

The tragic consequences of refused entry are illustrated by the example of hundreds of Germans of Jewish origin who tried in vain to leave Europe with the help of the St. Louis ship in 1939 .

In the late 1930s, the British government allowed thousands of children of Jewish descent to enter Britain by relaxing these regulations.

In the early 1940s, the Emergency Rescue Committee got it that politically persecuted intellectuals received a Danger visa for entry into the United States of America.

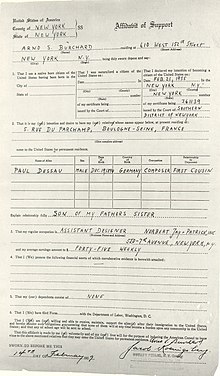

By issuing an affidavit , citizens of receiving countries could help obtain permission for persecuted and disenfranchised persons to enter. However, an affidavit did not automatically enable entry into the destination country, as the fate of Fritz Karsen shows. In 1935, his immigration to the USA failed despite an affidavit from Max Horkheimer, who had meanwhile moved the Institute for Social Research from Geneva to New York .

Shanghai occupied a special place as a place of refuge . No visa was required to enter the country . Werner Michael Blumenthal's family was one of the approximately 20,000 who fled to Shanghai .

Associations

German exiles founded associations in the receiving countries.

The engagement against the National Socialists continued from exile. The executive committee of the Social Democratic Party of Germany ( Sopade ) is an example of this, operating from Prague and Paris .

In the Union of German Socialist Organizations in Great Britain , socialist and social democratic exile organizations came together.

The German Labor Delegation was a social democratic organization in the USA .

The Heinrich Heine Club in Mexico , which worked closely with the communist-dominated movement “Free Germany” , provided a cultural forum . The other Germany , on the other hand, was more republican and pacifist . It was active in Argentina and tried to organize the anti-fascist struggle in South America with a magazine of the same name.

The Free German Cultural Association in Great Britain (FDKB) was established in England in 1939 and is to be regarded as the forerunner of the GDR's cultural association . In 1943, as a reaction to communist dominance in the FDKB, the 1943 Club split off and continued its activities after the end of the war; later under the name Anglo-German Cultural Forum .

In the spring of 1941, at the request of the Labor Party in Great Britain, the Union of German Socialist Organizations in Great Britain , supported by social democratic and left-wing socialist organizations, was founded , which initiated the establishment of the German Educational Reconstruction Committee (GER). Its aim was the planning and preparation of a reorganization of the education and training system in post-war Germany .

Death in exile

Exiles who openly opposed the National Socialists paid for their work with their lives, as the fate of Theodor Lessing illustrates.

Suicides

A number of suicides occurred in exile. For example, the writers Ernst Toller , Stefan Zweig and Walter Hasenclever as well as the emcee Paul Nikolaus committed suicide.

Walter Benjamin killed himself in the Spanish border town of Portbou because, despite having crossed the border, he still feared extradition to the Germans.

Return from exile

Some of the exiles decided to return to Germany after the end of National Socialism . Max Brauer and Ernst Reuter were among these.

The returned exiles met with rejection.

Failed return

The political conditions in post-war Germany meant that Jewish property seized by the National Socialists was not returned in certain cases. This is shown by the example of the manufacturer Hermann Lewandowski , who found refuge with his family in England. After 1945 his son Georg tried in vain to get the family-owned company back, which was located in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany . Hermann Lewandowski and his family did not return to Germany. At the same time, the story of the Lewandowski family shows that exiles were able to successfully build a new existence in the host country: Georg's brother Kurt Lewandowski founded his own company in exile, in which his father and brother were involved.

An example of a scientist's failed attempt to return is that of the literary scholar Walter A. Berendsohn. Berendsohn tried unsuccessfully to be able to work again as a university lecturer at the university where he had taught before 1933.

No less tragic is the story of Hans Weil , to whom the Senate of the Goethe University Frankfurt awarded a reparation professorship in the mid-1950s . Over a period of ten years, however, the university leadership failed to inform the Faculty of Philosophy about the established establishment of the professorship at which it was to be located. Weil was not informed either. In 1967 the university admitted its failure. At the same time, however, Hans Weil was informed that the professorship had become obsolete because he had now reached retirement age.

Participation of exiles in the military fight against the Nazi regime

There were a number of people who directly took part in the fight against the Axis powers after fleeing . So as deserters in the Resistance in France or the Soviet Union, as soldiers or in aid corps of the British and Americans. Artists participated in the propaganda against Nazi Germany. In post-war Germany, when they returned to Germany, some of them were massively criticized. Examples are the biographies of Thomas Mann , Bert Brecht and Marlene Dietrich . As foreigners in the exile states, they also had to deal with the problem of being observed as potentially hostile foreigners .

See also

- Kindertransport

- List of well-known German-speaking emigrants and exiles (1933–1945)

- List of emigrated German-speaking social scientists

literature

Essays

- Brita Eckert: The Beginnings of Exile Research in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945-1975. An overview [1] (56-page PDF document), in: Sabine Koloch (Hrsg.): 1968 in German literature / topic group “Post-War German Studies in Criticism” (literaturkritik.de archive / special editions) (2020).

Manuals

- Institute for Contemporary History (Ed.): Biographical Handbook of German-Speaking Emigration after 1933. Volumes 1–3. De Gruyter Saur, Munich / New York 1980, ISBN 3-59810-087-6 .

- Claus-Dieter Krohn , Patrik von zur Mühlen , Gerhard Paul , Lutz Winckler (eds.): Handbook of German-speaking Emigration 1933–1945. Primus, Darmstadt 1998, ISBN 3-89678-086-7 .

Individual groups of emigrants and host countries

- Andreas W. Daum , Hartmut Lehmann , James J. Sheehan (eds.): The Second Generation. Émigrés from Nazi Germany as Historians. Berghahn Books, New York 2016, ISBN 978-1-78238-985-9 .

- Daniela Gleizer Salzman: Unwelcome exiles - Exilio incómodo. Mexico and the Jewish refugees from Nazism, 1933-1945 . Brill, Leiden 2014, ISBN 978-90-04-25993-5 .

- Hans Peter Obermayer: German ancient scholars in American exile. A reconstruction. De Gruyter, Berlin et al. 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-030279-0 .

- Klaus Voigt: Refuge on Revocation. Exile in Italy 1933–1945. 2 volumes. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1989 and 1993, ISBN 3-608-91487-0 and ISBN 3-608-91160-X .

Web links

- Arnulf Scriba: Emigration from the Nazi State , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- Emigration and exile as a result of National Socialism 1933–1945 , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- Claus-Dieter Krohn: Emigration 1933–1945 / 1950 , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- Exile collections of the German National Library (DNB) , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- Society for Exile Research , accessed February 23, 2017.

- Arts in Exile , Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- Holdings of the German Exile Archive

- Marina Aschkenasi: Jewish remigration after 1945 . In: From Politics and Contemporary History , 42/2014, accessed on February 23, 2017.

- Inge Hansen-Schaberg: Exile Research - Status and Perspectives . In: From Politics and Contemporary History, 42/2014, accessed on February 23, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Emigration and Exile as a Result of National Socialism 1933–1945 , p. 1 , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- ↑ Emigration and Exile as a Result of National Socialism 1933–1945 , p. 1 , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz: Die Judenische Emigration In: Claus-Dieter Krohn (Ed.): Handbuch der Deutschensprachigen Emigration 1933-1945 , Darmstadt 1998, pp. 5-14

- ↑ September 1941: Introduction of mandatory labeling for Jews in the German Reich , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- ^ Film and Exile in the Third Reich , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- ↑ Oksana Bulgakova : Workers of all countries, have fun! In: The daily newspaper of February 9, 2012.

- ↑ Michael Grüttner / Sven Kinas: The expulsion of scientists from German universities 1933–1945 , in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , Issue 1 (2007), pp. 123–186, here pp. 141 and 143.

- ^ Arnulf Scriba: Emigration from the Nazi state , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- ↑ Emigration and Exile as a Result of National Socialism 1933–1945 , p. 1 , accessed on February 23, 2017.

- ↑ See Marina Aschkenasi: Jewish remigration after 1945 . In: From Politics and Contemporary History, 42/2014, accessed on February 23, 2017.