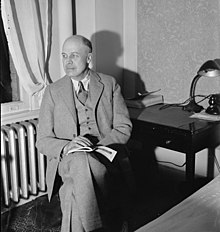

Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper (born July 22, 1882 in Nyack , New York , † May 15, 1967 in New York City , New York) was an American painter of American realism . Hopper's cool, realistic pictures point to the loneliness of modern people and the emptiness of modern life. He is considered a chronicler of US civilization.

biography

Youth and education

Edward Hopper was born in Nyack, New York in 1882, the second child of Garret Henry Hopper and Elizabeth Griffiths Smith Hopper, the family was Baptist , the father ran a small textile and haberdashery shop. Hopper was of English-Dutch- Welsh descent. His sister Marion was born two years before him. Like most children, he occupied himself with drawing, signing his drawings from the age of ten. His parents did not oppose his wish to become an artist. The view of the Hudson River aroused his enthusiasm for boats and racing yachts. At the age of 15 Hopper built a small sailing boat ("catboat"). Since the young Hopper loved sailing, he also considered a career as a naval architect. Edward Hopper's interest in American architecture began as a child and has continued throughout his career.

In 1899 he finished high school . From 1900 to 1906 he studied illustration with Frank Vincent DuMond and Arthur Keller and painting with William Merritt Chase and Kenneth Hayes at the New York School of Art and Design, the forerunner of the Chase School (now Parsons The New School for Design) Miller and Robert Henri , the mentor of the Ashcan School . In addition to his intense preoccupation with German, French and Russian literature, painters such as Diego Velázquez , Francisco de Goya , Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet offered the young artist important points of reference.

In 1906/1907 and 1909/1910 he toured Europe with financial help from his parents and visited, among others, Paris with the Salon d'automne , as well as London, Brussels, Amsterdam and Haarlem as well as Berlin. In Paris, where he lived with a French family, his love for impressionism was awakened by his fellow student Patrick Henry Bruce and visits to museums. Bruce introduced him to the painters in Paris. Hopper was particularly interested in the works of Pierre-Auguste Renoir , Alfred Sisley and Camille Pissarro . His second trip to Europe also took him to Madrid and Toledo in May and June 1910.

Work as an illustrator

From 1905 Hopper worked as an illustrator for advertising agencies (especially for C. C. Phillips & Co.), part-time in the first year, later freelance. This activity, important for earning a living for the next 16 years, he did not see as part of his artistic work. Hopper couldn't make a living from painting until he was 42. He participated in exhibitions at the McDowell Club, directed by Robert Henri, where he was able to record his first financial success as an artist with etchings. In 1913 he took part in the Armory Show in New York City and sold his first painting, Sailing, for $ 250 . It was the first and for the next ten years the only painting he was able to sell. Since 1914 Hopper was a member of the Whitney Studio Club, which had been founded by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney . His friend and artist colleague Martin Lewis taught him the technique of etching in 1915. From 1915 onwards he made a few little-known etchings . Hopper himself described the introduction as enormously important for his further work: "After I started etching, my paintings crystallized." During the First World War, Edward Hopper earned recognition as a poster artist from clients, audiences and critics. Hopper won a United States Shipping Board poster competition in 1918. In January 1920, when Hopper was already 37 years old, he exhibited as a solo exhibitor at the Whitney Studio Club paintings curated by his friend, the artist Guy Pène du Bois. From 1922, the first articles about him appeared in art magazines. All his life Edward Hopper carried a note in his jacket pocket on which he had written a quote from a letter from Goethe. Hopper had learned German at school. The quote read: “ Look, what is the beginning and end of all writing, the reproduction of the world around me, through the inner world that grabs, connects, recreates, kneads everything and puts it back in its own way, that remains eternal secret, thank God, that I don't want to reveal to the gawkers and gossips either. “(Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in a letter to Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, August 21, 1774).

First successes as a painter

In 1915, Hopper met the painter and actress Josephine Verstille Nivison (called "Jo") in Gloucester (Massachusetts) , whom he married on July 9, 1924. She largely gave up her own painting and became the favorite model most often shown in Hopper's pictures. It was also she who conveyed his participation in an international group exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum of Art , which meant the breakthrough for Hopper. The Brooklyn Museum of Art bought The Mansard Roof (1923) for $ 100. It was the second painting Hopper was able to sell. That year his first commercial solo exhibition took place in Frank Rehn's gallery, who remained his gallery owner until the end of his life .

Recognized artist

During the Great Depression he became a well-known and recognized painter in the USA. For example, in 1929 Hopper sold two oil paintings , 14 watercolors, and 80 graphics for a total of $ 6,211. Economic success did not emerge until 1930, after the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired pictures from Hopper the following year. As early as 1933, the Museum of Modern Art showed a retrospective that Alfred H. Barr organized at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was open from November 1 to December 7, 1933. The exhibition sparked a public debate as to whether Hopper's pictures were actually “modern enough” to be exhibited at MoMA. The critic Clement Greenberg accused Hopper of being a "bad painter", whose technical inadequacies, however, made him a "superior artist". Hopper, however, moved far away from the discourse of “modern” art.

Between 1935 and 1937 he won four important prizes, which were followed by many more.

In 1941 he toured the west coast of the United States by car . The first trip to Mexico followed in 1943 . In 1945 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters . In 1950 the Whitney Museum held its first major retrospective, which was also shown in Boston and Detroit . In the same year he received an honorary doctorate from the Art Institute of Chicago . In 1952 he and three other painters represented the USA at the Venice Biennale .

In 1960 Hopper expressly opposed the predominance of abstract art in painting at the time. In the same year the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford (Connecticut) showed an exhibition of his works. In 1962 there was a retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art ; A second followed in 1964 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Edward Hopper painted his last oil painting in 1966 with Two Comedians (private collection). It shows the painter and his wife as actors, who are just saying goodbye to their audience.

Edward Hopper died on May 15, 1967 in his New York studio on Washington Square , where he had lived continuously since December 1913. He found his final resting place two days later in the family grave in Oak Hill Cemetery in his birthplace Nyack , New York. When Hopper died in 1967, many of his pictures had long had the status of icons of modernity in Europe too.

His wife Josephine passed away on March 6, 1968. The couple had remained childless.

Museums

According to Hopper's request, the works of art were given to the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan . The estate comprised more than three thousand paintings, drawings, watercolors and graphics. The museum thus has the largest collection of Hopper's works in the world. The Sanborn family, who were friends with Hopper, donated 4,000 archival documents from Hopper's estate to the Whitney Museum.

Exhibitions (posthumously)

- In 1979 the third retrospective was shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art . Parts then migrated through Europe.

- In 2004/2005 a cross-section with almost 70 of his works was shown in London and then in Cologne ( Museum Ludwig , 358,000 visitors). In the course of three months, his work was viewed by 420,000 visitors in London's Tate Gallery . The exhibition Modern Life took place in the Bucerius Kunst Forum in Hamburg until the end of August 2009 . Edward Hopper und seine Zeit , which in addition to Hopper's works also showed works by his contemporaries such as Man Ray , Lyonel Feininger , Charles Sheeler and Georgia O'Keeffe .

- In 2012/2013, a retrospective on Edward Hopper was organized for the first time at the Grand Palais in Paris.

- The Fondation Beyeler will be showing the landscapes and urban landscapes of Hopper between January 26th and May 17th, 2020 (extended until September 20th). However, Nighthawk's iconographic work cannot be seen because its meaning would too easily outshine that of the other works, according to curator Ulf Küster . Part of the exhibition is a 3D short film by director Wim Wenders entitled Two or Three Things I Know about Edward Hopper .

Work and themes

Oeuvre

Hopper's work can predominantly be assigned to realism, it shows numerous facets of this style. Typical for Hopper are iconic depictions of the vastness of the American landscape, urban landscape and people. Many works show a figurative painting that heralds the later Pop Art (Hopper was like Andy Warhol commercial artist). Hopper's work includes watercolors, etchings and oil paintings from the 1910s to 1960s, which are characterized by silence and simplicity. Around 1920, Hopper went from an impressionism , of paintings painted in the open air , to a calm, haunting realism that can be described as his very personal handwriting, in the sense of a consistent visual language. This New Realism (American Realism), probably also influenced by the New Objectivity , creates a tension in the viewer through its objectivity. Often it also shows an enigmatic drama that only gradually becomes apparent to the viewer. The viewer wonders what preceded the scene and what will soon follow. They act as a (almost photographic or cinematic) snapshot (American stills) within a stage play or film. The people in these pictures are actors and actresses in front of a backdrop. Seen from a different perspective, Hopper's pictures have a narrative element: They tell stories, open, incomplete, possible and impossible at the same time. And sometimes the narrative also seems eerie, almost hitchcock-esque . Hopper likes to encrypt anyway by reflecting on and commenting on a political, social reality of the USA with his artistic and poetic forms of expression. But there is another interpretation of the artist's concern: Hopper succeeds in making the viewer aware of the elsewhere, the absent, the longed for, the puzzling. You also have to take into account that he manages to express a remarkably atmospheric mood in his works with surprisingly little effort, probably due to his routine as an illustrator and commercial artist.

style

Painting was a private experience for Edward Hopper. Edward Hopper's painting style remained relatively unchanged throughout his life, with a very stable, uniform visual vocabulary. He developed his mature style, content and form, during the 1920s. Hopper's characteristic themes:

- Landscapes: Classic landscapes, such as slightly undulating mountains, dunes. Lighthouses as an alter ego , such as Cape Cod Morning (1950), self-portraits of a solitaire in a rough nature - this interpretation comes from Josephine Hopper. He staged American landscapes as wide spaces, occupied by simple wooden houses and little infrastructure, characterized by human civilization in a dominant nature.

- Urban motifs: cityscapes, some with technical details, deserted streets that are brought to life by the sun. His night pictures often offer insights into individual rooms with one or two people. The viewer retains the freedom to interpret the relationships, conversations and consequences of the scenes.

- Indoor / outdoor spaces: Hopper's secret are also mundane motifs from everyday life, small-town, monotonous to banal scenes as well as a connection between indoor and outdoor space. B. one or more people are in an interior with a view. For Hopper, the inner world means: descriptions of reality, but far removed from the surfaces, more profoundly founded, expressing people's “soul life”, their feelings. At Hopper, people are basically landscapes.

- Femininity: Images of individual women of the type of his wife (clothed and naked). Time and again, Hopper's mostly female characters seem to do nothing more than look at the day and leave themselves, on their skin, to the sun, to the relentless, unstoppable, fateful passage of time.

- Play of light: light-dark contrasts , sunlight and strong shadows in rooms or in the landscapes follow a sophisticated lighting scheme. He stages stage lights and strong spotlights.

- Time of day : Most images show sunlight or night light, as is typical for one hour of the day: morning, noon, evening, night.

- Acting character: The theme of “stage design” could correspond to the role of the spectator, which recurs again and again in the work, and which occupied him again and again from the first sketch sheets to his last work in oil, Zwei Komödianten . The reason: Josephine and Edward Hopper were avid theatergoers and passionate moviegoers. One reason why Hopper's paintings with their seemingly everyday objects create such an unusual tension is their stage-like nature. Hopper's pictures often look like a stage set and the people depicted look like actors and actresses.

- I-reference: His pictures are projections of his personal mood or self-observation.

- The emptiness of modern life as a social criticism: its themes have often been interpreted as expressing isolation , loneliness and exclusion of the individual. His protagonists read, look out the window, look past each other. The people depicted often seem to have sunk into melancholy . His paintings often show the individual in dinners, hotel rooms, train compartments, offices, waiting rooms or in front of house facades, therefore often in public spaces. The looks of several people shown usually pass each other and thus illustrate distance despite spatial proximity. But there are always individual pictures of related groups of people. Hopper shows the emptiness of modern life.

- Architecture: For buildings, he often focused on their abstract shapes rather than their aesthetics. Hopper repeatedly assessed the merits of cities he visited based on their architectural qualities. Hopper explored the architecture of both rural and metropolitan America like no other artist.

Hopper's color palette contains numerous green-blue and white-blue tones and shades, often with hard light. This gives the viewer the impression of coolness and distance. Hopper's works often show a provocative emptiness.

Degas influence

Jo gave her husband a book about Edgar Degas as inspiration in 1924 . Degas was the main representative of the figurative direction of impressionism. This impulse must have been very important, like so much of what his wife did to support her husband. From the 1920s, when his style clearly crystallized, Hopper's works show a clear understanding of Degas' compositional strategies. This was shown by heavy cropping, extreme diagonals and unusual visual perspectives, in principle methods of artistic photography . Hopper adopted the concept of the ornamentally organized pictorial space from Degas. The composition of his pictures, according to Hopper, is only a section (he shows further sections in the windows). The viewer has the feeling that it is a still image of a film. With this, Hopper achieved incessant (mental) movement in his pictures despite all the calm.

Work style

Edward Hopper's work is astonishingly small; only 366 oil paintings are known. Finding a motif was an extraordinarily complex process for the American painter. For months, even years, he was looking for the ideal motif that correlated with an inner image. The complexity of beginning a painting and its flight from it resulted in countless visits to theaters and cinemas, but above all in intensive reading. Hopper also showed a keen interest in contemporary photography.

Hopper over hopper

Hopper saw himself as an “impressionist”, “realist” or “social realist”. In doing so, he turned against abstract art in American painting at the time.

In 1939, Hopper stated in a letter:

“For me, shape, color and composition are just a means to an end, the tools I work with, and I'm not particularly interested in them for their own sake. I am primarily interested in the broad field of experience and sensation. […] I mean the general human experience, mind you, so that you don't run the risk of being confused with the superficial anecdote. Images that are reduced to color or compositional harmonies or dissonances repel me. / It has always been my goal, based on the feelings and sensations that nature inspires me, to bring my innermost perception of a subject that triggers the most intense feeling in me onto the canvas; the quality of my relationship to this subject, my preliminary decisions give form to the representation. [...] Art is so much an expression of the unconscious that it seems to me that it owes the most important things to the unconscious and that consciousness only plays a subordinate role. But a psychologist should better unravel these things. "

The most systematic explanation of the philosophy of his art was given by Hopper on a handwritten note with the title "Statement", which he sent to the journal "Reality" in 1953 (excerpts):

“Great art is the outer expression of an inner life of the artist, and this inner life will lead to his personal vision of the world.

No number of clever inventions can replace the essential element of the imagination.

One of the weaknesses of abstract painting is the attempt to replace the inventions of the human intellect with a personal, imaginative conception.

A person's inner life is a vast and diverse realm and is not just concerned with stimulating arrangements of color, shape and design.

The term life used in art is something that should not be despised because it implies all existence, and the principle of art is to react to it and not to ignore it.

Painting has to deal more fully and less unrealistically with life and natural phenomena before it can become great again. "

Hopper on his realism:

“I am a realist and react to natural phenomena. Even as a child I noticed that the sunlight on the upper part of the house is different than on the lower part. The sunlight on the upper part of the house creates a kind of excitement. You know, there are many thoughts, many impulses in a picture - not just one. For me, light is an important means of expression. But I am not particularly aware of it. I think light is a natural expression for me. [...] The sunlight on the buildings and the figures interests me more than any symbolism. "

Hopper on the American Scene :

“What drives me crazy is all this American scene hype. I've never tried to recreate the American environment like Benton, Curry, and the Midwestern painters. I always wanted to express myself. "

Comments

John Updike commented:

“The human being was Hopper's main subject, although he wasn't particularly good at drawing people. They often appear stiff and pale ... Nevertheless, we find his portraits of the human condition more moving and impressive than those of much more lively illustrators like Reginald Marsh and Thomas Hart Benton . To use a sentence normally reserved for writers, he is a master of tension. "

Ingeborg Ruthe von der Frankfurter Rundschau called him in 2018 "chronicler of American society."

Gordon Theisen said that as common ground for social criticism in the US, Hopper showed the "broken American dream."

Works

Overview

Due to the way he worked, his work can be divided into the following periods, which, however, were remarkably uniform:

- 1893 to 1901, orientation

- 1902 to around 1922, early work

- 1923 to around 1930, breakthrough

- 1931 to 1950, Zenit

- 1951 to 1967, late work.

Hopper painted a total of 724 paintings. 326 of these are on display at the Whitney Museum of American Art today . 21 paintings have been lost to this day.

"Nighthawks" (1942)

| Nighthawks |

|---|

| Edward Hopper , 1942 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 84.1 x 152.4 cm |

|

Art Institute of Chicago , Chicago

Link to the picture |

Nighthawks from 1942 is one of the most popular images of the 20th century. For this picture, Hopper was inspired by a “restaurant on Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet”. In the cool, artificial light atmosphere of a bar , three guests are sitting, looking past each other, not talking and seemingly thinking about their own thoughts. Do you lack the courage to address other guests? The night owls sit or stand at the surrounding counter, in the middle of which the white-uniformed waiter works. Whether the woman, whose left hand points to the smoking man on her right, and he are a couple, or whether they want to get to know each other, remains open. The other man, sitting alone, is a part of his back, also he with a hat. As is so often the case, Hopper's accents are isolation and loneliness. Despite the number of people in the bar who are not in direct contact, the night owls are basically "lonely souls" on a night without contacts.

Nighthawks has been copied and cited countless times. There are versions in various comics such as Simpsons , Tintin and others, as well as numerous advertising motifs that relate to Hopper's most famous picture. The best known are Marilyn Monroe and Humphrey Bogart as a late couple in the picture Boulevard of Broken Dreams by Austro-Irish artist Gottfried Helnwein .

"Gas" (petrol) (1940)

| gas |

|---|

| Edward Hopper , 1940 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 66.7 x 102.2 cm |

|

Museum of Modern Art , New York

Link to the picture |

The picture Gas (petrol) from 1940 shows a gas station in front of threatening trees at dusk from the perspective of an approaching motorist.

Three bright red gas pumps from a gas station in front of a wooden house on a street with no traffic in an apparently very lonely area. It almost looks like a still life from the frontier of civilization. The road is lined with low, yellow-red grass. In the background, under the section of an already dusky blue sky, a dark, gloomy forest. At the front pillar, seen in profile, is a gas station attendant, busy with a function of the gas pump. With Hopper you can determine the time of day with the light that he gives to a scene. Here, at the petrol station at dusk, a light source is already burning inside the wooden house and the "Mobilgas" sign is also lit, it will soon be night. Hopper controls the light like the illuminator on a theater stage. The imagery reads like an enigmatic riddle that the viewer should solve.

"Ground Swell" (1939)

Ground Swell from 1939 is a maritime motif, a subject that has fascinated Hopper since his youth on the Hudson. The title of the work comes from a natural phenomenon in which buoys in the sea are triggered by distant storms, which cause waves (swell), and therefore warn when there is actually no real danger (yet). This concept of a threat in a calm, natural environment goes back to an inspiration from Hopper, by the French artist Nicolas Poussin , whose paintings also influenced the appearance of the four figures in Ground Swell. At first glance, Ground Swell is a very calm, relaxing work that is initially gentle on the beholder's eye and preserves the traditional aesthetic value. It uses a bright color scheme that lulls the viewer into a sense of security as the work reveals a deeper level of impending danger on closer inspection. Although the painting shows a group of sailors at its core, none of the people interact with each other, creating a feeling of isolation and loneliness despite the group's physical proximity. It's the themes and accents from Hopper. The position and perspective of the painting give an impression of the voyeurism of the indifferent observer. The fixation of the figures on the buoy gives Ground Swell an almost dramatic note, which is reinforced by the waves of the swell that dominate the work.

"House by the Railroad" (1925)

The picture House by the Railroad from 1925 shows a lonely Victorian house on a railway line . The residents cannot be seen. Sunlight with a sharp shadow cast determines the work. The color scheme is quite cool with blue, gray and white. Here, too, it is up to the beholder to interpret whether the train tracks are a synonym for the abandonment of the unknown residents, as trains passing by will not stop due to the lack of a platform. The picture was added to the museum's permanent collection in January 1930 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City as the first painting ever.

"Early Sunday Morning" (1930)

In a picture like Early Sunday Morning from 1930, the meaning lies in the long shadows, the sunlight on flat reddish bricks, the streak of almost cloudless sky, the yellow shutters divided by shadows, and the barbershop sign. It conveys a rapture. The reason: Early Sunday Morning was painted from an unfamiliar perspective: the viewer and painter seem to float at the height of the windowsill on the second floor, too close to be in a building on the opposite side of the street for this perspective, and yet higher than at street level. On Early Sunday Morning Hopper retrospectively painted over a person who could be seen in one of the windows.

"Two Comedians" (1966)

The picture from 1966 was Hopper's last oil paint job. His penultimate work ever. This time Hopper does not quote a stage or a stage light, as usual, he shows a stage. The picture shows a woman and a man on a stage, dressed as harlequins in the style of a commedia dell'arte , who obviously receive the final applause. She, with a hood and the pleated wagon wheel collar of Columbine, he as a tall, almost Shakespearean figure with a red velvet beret and a collared doublet. It must be assumed that the characters represent Edward and Jo Hopper. However, he paints them without a stage set, so that the two actors catch the eye as the central motif. A multiple metaphorical motif with a humble, serene gesture. The picture, painted shortly before his death, looks melancholy and symbolizes the farewell to the stage of life.

Picture gallery

Influences on painting, photography, film and cinema

Hopper's realism resulted in bridges to photography. His style has been cited in their works by photographers such as Joel Meyerowitz (“the hopper of photography”), Gregory Crewdson , Stephen Shore , Jeff Wall and Dolorès Marat, or by painters like Ed Ruscha .

The strong atmosphere of his works inspired , among others, film directors such as Alfred Hitchcock , of the Bates Motel in Psycho Hopper's painting House by the Railroad took (1925) as a model. Michael Curtiz 's film Casablanca was built in the same year 1942 as Hopper's Nighthawks ( revelers ). In the film, a man ( Humphrey Bogart ) stands next to a beautiful woman ( Ingrid Bergman ) in a bar. In Hopper's picture, a man sits next to a beautiful woman in a bar. The consistency of the theme seems to reflect the attitude towards life in America in the 1940s , in which mental problems, beautiful women and bars play a role.

For the atmosphere of the film Blade Runner , director Ridley Scott is also said to have used Hopper's image Nighthawks as a template, as several members of the film crew reported. The Italian Giallo director Dario Argento created a street scene in his thriller Profondo rosso (1975) as a complete reconstruction of Nighthawks .

The German director Wim Wenders also used Edward Hopper's works as a template and inspiration for films, for example in The Million Dollar Hotel (2000) pictures such as The Morning Sun (1952). Wenders once said that each of Hopper's pictures could be the beginning of a new chapter in a great film about America.

In his film Der Kalmus (2009), the Polish director Andrzej Wajda tried to reproduce the atmosphere of Edward Hopper's images for a monologue by his leading actress Krystyna Janda . In 2013 the film was released Shirley - Visions of Reality (dt .: Shirley - The painter Edward Hopper in 13 pictures ), written and directed by Gustav German . In this film, figurative paintings from Hopper's oeuvre are recreated with actors.

literature

Monographs

- Gail Levin: Edward Hopper - An Intimate Portrait. List, Munich, 1998, ISBN 3-471-78062-9 .

- Gail Levin: The Painted Reality - Edward Hopper and his America. List, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-471-78067-X .

- Gail Levin: Hopper's Places. Random House USA, 1985; 2nd edition: University of California Press, 1998, ISBN 0-520-21676-8 .

- Ivo Kranzfelder: Hopper. Taschen, Cologne, 2002, ISBN 3-7913-3300-3 .

- Rolf G. Renner: Edward Hopper 1882–1967: Transformation of the Real. Taschen, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-8228-6597-4 .

- Wieland Schmied: Edward Hopper - Portraits of America. Prestel, 2005, ISBN 3-7913-3300-3 .

- Didier Ottinger: Edward Hopper - America - light and shadow of a myth. Schirmer / Mosel-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-8296-0634-9 .

Work descriptions

- Edward Hopper, Gail Levin: Edward Hopper 1882–1967. Paintings and drawings. Modifications made by Gail Levin. Mosel, Munich 1981.

- Edward Hopper: Catalog raisonné in four volumes. All paintings, watercolors and illustrations. / CD-ROM. Catalog work New York 1995. Ed .: Gail Levin. (352 p. Per volume, 1,500 illustrations and images)

- Deborah Lyons (Ed.): Edward Hopper: A Journal of His Work. WW Norton Publishing, London 1997, ISBN 0-393-31330-1 (English).

- Virginia M. Mecklenburg, Edward Hopper, Margaret Lynne Ausfeld: Edward Hopper: The Watercolors. WW Norton Publishing, London 1999, ISBN 0-937311-57-X (English).

- Gail Levin: The Complete Oil Paintings of Edward Hopper. WW Norton, London 2001, ISBN 0-393-04996-5 (English).

- Gail Levin: The Complete Watercolors of Edward Hopper. WW Norton, London 2001, ISBN 0-393-04995-7 (English).

- Sheena Wagstaff (Ed.): Edward Hopper. Exhibition catalog London / Cologne 2004/2005. Hatje-Cantz. 2nd edition 2004, ISBN 3-7757-1500-2 .

- Heinz Liesbrock: Edward Hopper. The truth of light. Trikont, Duisburg 1985, ISBN 3-88974-102-9 .

Movies

- Hopper's Silence. Documentary, USA, 1980, 47 min., Script and director: Brian O'Doherty, production: Whitney Museum of American Art , summary of the New York Times .

- Edward Hopper: Night Owls 1942, oil on canvas. Image analysis, Germany, 10 min., 1988, director: Reiner E. Moritz , book: Gisela Hossmann, series: 1000 masterpieces , production: RM Arts, WDR .

- Edward Hopper - Pictures of the American Soul. Documentary, Germany, 2002, 43 min., Script and direction: Eike Barmeyer, production: B3 , first broadcast: June 22, 2002, summary by BR-alpha .

- The eye of Edward Hopper (Original French: La Toile blanche d'Edward Hopper) . Documentary, France, 2012, 52 min. Written and directed by Jean-Pierre Devillers, François Gazio and Didier Ottinger. Production: ARTE France, Idéale Audience, Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais, avro, Center Pompidou . First broadcast in Germany on October 14, 2012, film dossier from arte with Wim Wenders and others .

- Hopper revisited… (Hopper vu par…) . Short film series with 8 four-minute contributions, France, 2012, 52 min., Directors (1 × each): Valérie Pierson, Martin de Thurah, Hannes Stöhr , Mathieu Amalric , Dominique Blanc , Sophie Fiennes , Valérie Mréjen, Sophie Barthes, production: En haut des marches, ARTE France, first broadcast: October 14, 2012, film dossier with video clips from arte. (Eight European directors were inspired by Hopper's pictures to make short films.)

- Edward Hopper, a stranger in Paris. Documentary. France, 2019, 14 min. Arte . on-line

- Edward Hopper's melancholy New York. Documentary. France, 2018, 14th min. Arte. on-line

- T wo or Three Things I Know about Edward Hopper , 3D short film by Wim Wenders .

Web links

- Literature by and about Edward Hopper in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Edward Hopper in the German Digital Library

- Search for "Edward Hopper" in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Edward Hopper at artfacts.net

- Edward Hopper in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Artcyclopädia: paintings in museums, galleries and related links

- Edward Hopper on artnet

- Edward Hopper on Wikiart

Photo credits

- ↑ Nighthawks - Nachtschwärmer (Note on the color reproduction of the prints and on the web: So far, none of the many repro processes has succeeded in matching the shimmering blue-green of the dominant windows of the original)

- ↑ Gas - petrol

- ↑ House by the Railroad - Haus am Bahndamm (accessed on February 24, 2010)

- Edward Hopper at the National Gallery of Art

- Hopper in the WebMuseum, Paris (picture examples for three topics: interiors, streets, landscapes)

- Early Sunday Morning, 1930

Individual evidence

- ↑ The motif of loneliness is the most obvious and central motif in Hopper's works, which is also often emphasized by critics. On the other hand, Hopper himself asked not to overemphasize this aspect in the interpretation of his works: The loneliness thing is overdone. http://www.edwardhopper.net/ , accessed September 25, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ivo Kranzfelder; traduction Annie Berthold: Edward Hopper 1882–1967 - Vision de la réalité . Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-8228-2048-2 , p. 7-13 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Edward Hopper: style, subjects and the painter's most famous picture. In: Art, artists, exhibitions, art history on ARTinWORDS. Accessed January 31, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c Fondation Beyeler: Edward Hopper. Fondation Beyeler, 2020, accessed on January 31, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Edward Hopper: Style, Subjects and the Painter's Most Famous Picture. In: Art, artists, exhibitions, art history on ARTinWORDS. Accessed January 31, 2020 .

- ^ Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism . In: John O'Brian (Ed.): Review of the Whitney Annual - The Nation . tape 2 . Chicago December 28, 1946, p. 118 .

- ^ Members: Edward Hopper. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed April 4, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Ingeborg Ruthe: Farewell to the stage of life. Frankfurter Rundschau, November 15, 2018, accessed on February 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Edward Hopper's grave at knerger.de

- ^ Whitney Museum gets thousands of Hopper documents. In: Hamburger Abendblatt . July 31, 2017, p. 15.

- ↑ retrospective Edward Hopper , visitparis-cultureguide.parisinfo.com, accessed January 28, 2013.

- ^ Badische Zeitung: The Fondation Beyeler shows landscapes by Edward Hopper - Art - Badische Zeitung. Accessed January 31, 2020 .

- ↑ Edward Hopper. Accessed January 31, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h John Updike: Art: Master of tension . In: The time . May 27, 2004, ISSN 0044-2070 ( zeit.de [accessed January 31, 2020]).

- ↑ a b c Peter Iden: Edward Hopper: Silent scenes of a true sensation. Frankfurter Rundschau, January 29, 2020, accessed on February 1, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d e Christiane Hoffmans: Images of the loneliness of man . In: THE WORLD . October 2, 2004 ( welt.de [accessed February 1, 2020]).

- ^ Edward Hopper, in a letter to Charles H. Sawyer, director of the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts, 1939

- ↑ Edward Hopper, "Statement." Published as a part of "Statements by Four Artists" in Reality , vol. 1, no.1 (spring 1953). Hopper's handwritten draft is reproduced in Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography , p. 461.

- ^ Katherina Kuh, The Artist's Voice. Talks with Seventeen Artists, New York 1962, S: 140 and 134. Quoted from Sheena Wagstaff, Enthusiasm for sunlight, in: Sheena Wagstaff (ed.), Edward Hopper (Aust.-Kat. Tate Modern, London, 27.5. –5.9.2004; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 9.10.2004–9.1.2005), Ostfildern-Ruit 2004, pp. 12–29, here p. 12.

- ↑ Christiane Hoffmans: Pictures of the loneliness of the people. In: welt.de . October 2, 2004, accessed May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ John Updike: Art: Masters of Tension. In: The time. May 27, 2004, ISSN 0044-2070 (zeit.de [accessed January 31, 2020]

- ^ Ground Swell Edward Hopper Painting. HopperPaintings.org, accessed February 1, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Tim Ackermann: Once upon a time in America. In: Welt am Sonntag . May 10, 2009, p. 86 for the Hopper exhibition Modern Life. Edward Hopper and his time in Hamburg, 2009.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hopper, Edward |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 22, 1882 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nyack , New York |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 15, 1967 |

| Place of death | New York City |