Erongo Mountains

| Erongo Mountains | ||

|---|---|---|

|

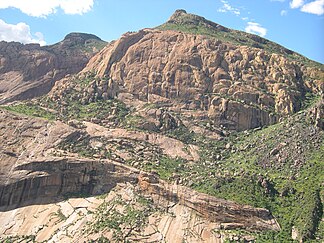

View of the Hohenstein in the massif of the same name, Erongo Mountains |

||

| Highest peak | Hohenstein ( 2319 m ) | |

| location | Erongo , Namibia | |

|

|

||

| Coordinates | 21 ° 40 ′ S , 15 ° 40 ′ E | |

| Type | Single solid | |

| rock | Volcanites and plutonites | |

| Age of the rock | 145 million years (basalts and andesites) to 132–130 million years (dazitic to rhyolite volcanics as well as granodioritic and granitic plutonites) | |

| surface | 1,000 km² | |

The Erongo Mountains (also Erongoberge , English Erongo Mountains ), historically Khoekhoegowab ǃOeǂgab , is a mountain formation of volcanic - plutonic origin in Namibia . It is located in Damaraland , southwest of the city of Omaruru , south of the river of the same name and east of the municipal area of the Damaras . The name of the region Erongo is derived from the Erongo Mountains .

geography

The Erongo Mountains have an average diameter of 35–40 km and are approximately ellipsoidal in shape and cover an area of approx. 1000 km². It extends from Omaruru (in the northeast) to the trigonometric point 1469.5 m (Kaichanab) near the intersection of roads D1927 and D1935 (in the southwest), its geographic center is at 21 ° 40 ′ south latitude and 15 ° 40 ′ East longitude. Other places in the vicinity are Okombahe (around 45 km northwest of the imaginary center of the Erongo Mountains), Usakos (around 40 km south) and Karibib (around 40 km southeast of this center).

"The Erongo rises as a huge block several hundred, in places over a thousand meters above the" Inclined Plane "of the edge step gap, which slopes steadily towards the Atlantic [...] Especially from the southwest, south and east, the mountains have a repellent and impenetrable character [...], since its enormous outer wall does not seem to be broken through by larger valleys anywhere. Only in the south is there a natural possibility of reaching the interior of the mountains via the "southern longitudinal valley" [...] This otherwise closed southern outer wall of the Erongo reaches the highest heights of the entire mountain range with 2319 m in the main summit of the Hohenstein . "

A 2206 m high, unnamed summit is separated from Hohenstein (formerly Davibeck ) by the Turtle Rock Gorge. The other striking mountains in the Erongo Mountains include (clockwise) two unnamed peaks (2037 m and 1850 m) on the western outer wall of the Erongo; the Grobe Gottlieb I and II (1746 m and 1694 m), the Krantzberg (1713 m) and the Omaruruberge on the north side of the Erongo; and finally the Erongoberg (2219 m), the Etirospitze, the Lion's Head and the Onguati corner (2072 m) as well as the Wilde Kopf (1566 m) and the Ameiber local mountain (1591 m) on the southern outer wall of the Erongo.

Continuously water-bearing rivers do not exist in the Erongo Mountains and its immediate surroundings. At best temporary water flow is only recorded in the case of occasional falling precipitation, when the rivers, called Riviere in this region , “come off”. The Omaruru (formerly Eisib) drains north of the Erongo Mountains and the Khan to the south , into which the Etiro flows from the northeast and the Davib from the northwest. The Khan itself is the largest tributary of the Swakop . The only major rivier in the interior of the Erongo is the Okondeka.

geology

construction

Where the outer walls of the Erongo Mountains are still preserved, the same structure can usually be found: while the lowest part of the outer wall is either formed by rocks from the basement or from Erongo granite , basalt layers of varying thickness follow it . Above that, porphyry ceilings are encountered, which mostly merge into ignimbrite in the summit area . The current morphology of the Erongo Mountains is determined by the petrographic composition of the individual units. Hard rocks (thin basalt layers , porphyries) are carved out on the walls as cornices or exposed as rock slabs. In particular, the Erongo granite is found in the form of characteristic smooth slopes, whereas the ignimbrites of the summit layers are designed as almost vertical rock walls. The softer rocks (the majority of the coarse porphyry series as well as rocks of the basement) are covered by trailing debris. Wherever the Erongo granite does not form smooth slopes, it can be found - especially on the farms Etemba, Anibib and Ameib - in the form of the grandiose rock castle landscapes. In contrast to its form, which is closed from the outside, the interior of the Erongo Mountains shows itself as a wide, multi-structured open space landscape. It consists of eleven more or less oval, intramontane individual basins.

Emergence

The flood basalts and the associated Felsic volcanic rocks of the early Cretaceous Paraná-Etendeka Province form a bimodal magmatic large province , which was formed during the breakup of the western Gondwana continent , i.e. when Africa and South America separated. This flood volcanism is associated with a number of sub-volcanic intrusive complexes that are particularly numerous and well-developed in the Namibian Damaraland. The Erongo complex is about 40 km in diameter and is the largest of these Damaraland ring complexes, including the Brandberg and the Spitzkoppe ; differentiated basic complexes such as B. Cape Cross, Messum and Okenyenya ; Carbonatite complexes like Kalkfeld, Okurusu, Ondurakorume and Osongombe as well as alkali complexes like Paresis and Etaneno count. Compared to the 450 million year old Damaraland Basement, the Erongo Mountains are much younger. Its genesis begins at the end of the Jura with the aforementioned effusive basaltic volcanism. All older rocks were covered by lava flows, which form the current edge of the Erongo Mountains. Subsequently, younger volcanic and plutonic (sub-volcanic) melts broke through this area and hardened on the basalt layer in a superstructure up to 400 m high. The feed channel for these melts is located in the Ombu basin and consists of an enormous granodiorite stock . Due to the rapid extraction, there was a mass deficit in the ground, which resulted in the collapse of the superstructure. This depression was greatest in the hearth area, which is why a lava bowl or caldera was created. That development was accompanied by an intrusive-explosive rhyolite volcanism , of which ignimbrites and tuffs , among other things, testify. The former outer walls of the volcanic building have been removed by erosion . Only the core of the original caldera structure is still there. It is surrounded in the northwest by a semicircular ring dike (ring-shaped rock dike ) made of tholeiitic dolerite , which has a diameter of approx. 50 km and which extends to the Waterberg-Omaruru fault zone, a NE-SW trending fault that is one of the the most important lineaments of the Damara Basement.

The Erongo complex consists of three dominant morpho-structural units:

- a massive central massif composed mainly of volcanic rocks with a diameter of approx. 30 km,

- several peripheral granite intrusions and distributed around the Massif Central

- a prominent semicircular ring dike made of tholeiitic dolerite about 50 km in diameter.

The Erongo complex was seated along the Waterberg-Omaruru Lineament, which was created during the neoproterozoic Damara orogeny and forms the boundary between two litho-tectonic zones of the Damara Belt. The adjacent rock consists of neoproterozoic metasediments (pelitic Kuiseb slates and metagrauwacken) of the Damara sequence and post-tectonic S-type granites of the early Cambrian age (Damara granite).

The Erongo Complex is characterized by a large variety of rocks and includes both felsic volcanic rocks and plutonites (sub-volcanic rocks), which either overlay or intrude the basaltic lavas belonging to the Etendeka Group. A distinction can be made between three main material groups:

- Tholeiites with a basaltic to andesitic composition,

- Vulcanites with Dacitic , trachydacite and rhyolite composition and the chemically equivalent, granodioritic and granitic intrusive rocks as well

- Alkali basaltic dykes and intrusive rocks ( basanites , tephrites , phonotephrites, foidites and trachytes ).

With the exception of the Ringdike dolerite, these groups represent individual phases of volcanic-plutonic activity following one another in time. The basis of the Erongo complex is formed by tholeiitic basalts, which were probably located at the end of the Jura (approx. 145 million years ago) and which took place in the Reach a maximum thickness of 300 m in the southeast of the complex. The basaltic volcanism was replaced by an intrusive-effusive magmatism, which produced rocks with rhyodacite to rhyolite composition in several thrusts , whereby details of the production mechanism are controversially discussed by the individual workers. On the one hand, post-basaltic volcanism is divided into two events, with the large-volume extraction of rhyodacite lavas followed by rhyolite ignimbrite eruptions; on the other hand, post-basaltic volcanism is divided into three individual events, with all volcanic rocks being viewed as pyroclastites . In the latter variant, andesitic to rhyodacite volcanic rocks were initially mined (Erongorus event with the Erongo ash stream tuffs, EAFT), to which volcanic rocks with rhyodacite to rhyolite composition of the subsequent ombu event (ombu event with the ombu ash stream tuffs, OAFT) followed. The EAFT are in the north, west and south-west of the Erongo complex and reach their maximum thickness in the western part. The OAFT occur in almost the entire complex and are only located in the center on the EAFT, while in the east, northeast and southeast they directly overlay the base basalts and reach a maximum thickness of up to 500 m. The ombu granodiorite represents the intrusive equivalent of the OAFT or rhyodacite. It forms the center of the Erongo complex in the form of a 6 × 15 km long stock. Rheomorphic rhyolites (Erongo event) overlay the EAFT in the west and southwest and the OAFT in the east. These rocks (rhyolite tuffs and ignimbrites) represent the extrusive equivalent of the Erongo granite, which is only intruded at the edge of the Erongo Complex. The third and stratigraphically youngest group is formed by tholeiitic and alkali-basaltic vein and intrusive rocks. This includes a ring dike, which has a maximum thickness of approx. 200 m and a diameter of approx. 50 km. The formation of the ring dike surrounding the Erongo complex in a semicircle also appears to be a consequence of a caldera collapse. In addition to the ring dike, the Erongo complex has a large number of corridors and storage corridors with a basaltic to rhyolite composition. The most recent event is the intrusion of predominantly alkaline basaltic magmatites. These occur in the north of the Erongo complex both as corridors and as sticks . The acid magmatism in the Erongo complex has a duration of only a few million years - possibly even less than 2 Ma. Considered in a regional context, the results of age dating in the largest complexes of Damaraland (Erongo, Brandberg, Paresis, Messum) indicate that the acid magmatism began simultaneously with the peak of the flood basalt effusion in the Etendeka province about 132 Ma ago and ended about 130 Ma.

history

In the C1 period of the Neolithic (between 4400 and 1200 BC) stone tools, stone cores, ostrich egg shells, ceramics and the first rock paintings and carvings were made in southern Africa . In the Erongo Mountains, such rock paintings and tool finds testify that parts of the mountains - like the dry regions of Southwest Africa in general - were at least temporarily inhabited and ancestors of today's San and Damara were habitat and home thousands of years ago. Especially in winter with little rainfall, the water-impermeable pans in the Erongo granite, which fill up in the rainy season, provided a reliable water supply for a long time. Another reason for the temporary settlement of the Erongo by the San is the abundance of game in the area. In the rocky mountains, the San preferred to spend the night in caves or crevices, the 15 m deep, 35 m long and 7 m high Phillips Cave on the Ameib farm being such a dwelling place for the San.

In the years 1885/85 the missionary Carl Gotthilf Büttner ( Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft ) discovered the rock paintings in the Phillips Cave, which were interpreted as prehistoric by the French researcher Abbé Henri Breuil in 1957. With the help of the radiocarbon method , their origin is estimated at 3368 ± 200 years BC. Dated. The best-known illustration shows a white elephant in which - probably afterwards - a red antelope was drawn. There are also paintings of giraffes, rhinos, ostriches, springboks, kudu and six human handprints.

Another cave with similar rock art is Paula Cave, located on Okapekaha Farm's private farmland in the Rock Badger Mountains near Omaruru . The Paula Cave offered the San both protection and a panoramic view of the area. The place may also have had a spiritual meaning for performing ritual dances - and the cave with the rock paintings was used to record these rituals. Henri Breuil also visited Paula Cave in 1950 and commented on the paintings as follows: “The rock wall on the left side of the cave is vertical and clearly concave. Various animals, including elephants and rhinos, appear behind the paintings of several tall, red-haired people with relatively long bodies. A group of black men with arrows can be seen further behind. These paintings are younger and only visible when dampened. Above and further back in the cave are a number of small, animal-headed and very mobile people in red who indulge in a kind of mantis dance. ”The“ White Elephant ”in Phillips Cave is particularly famous. The rock carvings in the Phillips and Paula caves, as well as the rock carvings on the Farm Etemba (home grotto and Etemba grotto), are National Monuments of Namibia in the area of "rock art". Well-known rock carvings can also be found on the farms of Anibib and Omandumba East.

Richter’s studies have shown that the respective environmental conditions led to very different cultural reactions in the way of life of Stone Age Namibian hunters and gatherers. In contrast to the Atlantic coast, Namib coast and Randnamib, the Erongo Mountains were populated both in summer and in winter. Typical settlement areas were ponds (for medium-sized, highly mobile groups in summer) and river beds (for small, less mobile groups in winter). Antelopes and large mammals as well as seeds, tubers and fruits were identified as food sources, with hunting activity being medium-high in both summer and winter, while foraging activity was very high in summer, while it almost came to a standstill in winter. In winter, however, jewelry production was very high.

Portuguese seafarers discovered the country for Europe as early as the 15th century, but there was no significant settlement for a long time due to the inhospitable conditions in the coastal regions. Beginning in the 17th century, the Herero , Nama , Orlam and Ovambo tribes invaded today's Namibia in the course of numerous African migrations . A stronger immigration of European settlers (including from the German-speaking area) did not begin until the end of the 19th century. The division of the area into farms dates from this time and is still in place today. Up until the very recent past, they were involved in both cattle and sheep breeding ( Karakul ). The Damaraland (and thus also areas of the Erongo Mountains) is still predominantly inhabited by the Damara, who, along with the San, are among the oldest inhabitants of Namibia. The Damara living in Damaraland - whose economic base is goat farming - are among the poorest ethnic groups in Namibia. Large parts of the Damaraland are heavily overgrazed today. The problems are that, on the one hand, pasture farming does not function without irrigation and, on the other hand, it leads to overgrazing and large-scale encroachment of the farmland and, in extreme cases, to desertification .

Hans Cloos and the Erongo

The name of the famous German geologist Hans Cloos (1885–1951) - and vice versa - is also associated with the term Erongo . After his studies, before the First World War, his uncle, Government Bergrat in what was then German South West Africa, invited him to do research in South West Africa. There, Cloos was able to deepen the practical knowledge he had acquired during his studies and, among other things, researched the Erongo Mountains. The result was one of the first descriptions of the physiography and geology of the Erongo Mountains with detailed rock descriptions and numerous geological sketches as well as the first black and white photographs of the Erongo Mountains. Just eight years later, Cloos published a comprehensive monograph on the Erongo, which also contained the first color geological map of the region. In his legendary “Conversation with the Earth”, Cloos once again dealt in detail with the “Sphinx Erongo”.

climate

In the Erongo, annual rainfall of 200–300 mm falls on average. Winter is dry, with most of the precipitation falling in the summer months from January to March. A “small rainy season” can precede in October / November. Typical for the Erongo is a fall below or above the mean values of 200–300 mm in z. T. considerable measure. For example, in the area of the Okandjou farm north of the Erongo, only 188 mm of precipitation fell in the 1972/72 rainy season, while a year later, with 521 mm of total annual precipitation, more than double the statistical mean. Precipitation not only falls unreliably and in a strictly rhythmic manner over the course of the year (extremely dry winters and precipitation concentration in the summer months), but is also developed during the precipitation period in such a way that periods of heavy rain alternate with periods of total dryness. Precipitation is often very concentrated locally and often only rains down from a single cloud. On April 1, 1974, 30 mm of rain fell on the Ombu farm, while the neighboring Koedoeberg farm did not receive a drop.

The data for the city of Omaruru should serve as an example of the climate in the Erongo Mountains. The climate classification of Köppen and Geiger , according to the climate in Omaruru type BWh - so it prevails desert climate with year-round rainfall barely. The annual average temperature is 20.5 ° C. Over the year, the rainfall adds up to 307 mm. The month with the lowest precipitation (0 mm) is July, the month with the most precipitation is February (79 mm). The wettest month, January, has an average of 72 mm more rainfall than the driest month. On an annual average, January is the warmest with an average temperature of 24.3 ° C, whereas June is the coldest month with an average temperature of 15.5 ° C. This means that the warmest month is on average 8.8 ° C warmer than the coldest month.

| Omaruru | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Omaruru

Source: Mapped Planet. Retrieved August 29, 2017 . Humidity, rainy days: weatherbase.com

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ecology

flora

The dry savannah with bushes and shrubs close to the ground extends over the majority of the Erongo Mountains . As soon as it rains, various savanna grasses also grow. Particular mention should be made of the Kobas and the Sprokies boom, which are as striking as they are characteristic of the Erongo Mountains.

The Kobas or Botterboom or Butter Tree ( Cyphostemma currorii ) is a tree up to three meters high that is mainly found on rocky ground. The juice that leaks from the trunk is used to treat cattle mange and dermatological diseases. The Kobas, protected by the Nature Conservation Ordinance of Namibia , bears fruit and leaves from October to May.

The Sprokies boom ( Moringa ovalifolia ), which reaches a maximum height of eight meters and mainly grows on cliff-like steep slopes, is also widespread . Its special appearance is created by the disproportionate thickness of the trunk, a diameter of up to one meter. The Sprokies Boom is known for its seed oil, which contains antibiotic substances and is therefore used as medicine. Like the Kobas, the Sprokies Boom is also protected and bears fruit and leaves between November and May.

The worm bark or cherry blossom tree ( Albizia anthelmintica ), the coral tree ( Erythrina decora ), the two-colored raisin bush ( Grewia bicolor ), the hoodia ( Hoodia currori ), the Bergaloe or Windhoekaalwyn ( Aloe Kaalwyn littoralis ), the monteiroi ( Euphorbia monteiroi subsp. Brandbergensis ), the camel thorn tree ( Vachellia erioloba ), the birch bark acacia ( Acacia erubescens ), the hooks mandrel acacia ( Acacia mellifera subsp. Detines ), the Südwester laurel tree ( Maerua schinzii ), the bush tea ( Ocimum canum ) and the snake egg bush ( Maerua juncea ). From the area of the Ameib farm in southern Erongo, Hannah Schreckenbach also has the endemic resurrection plant or “intrepid dwarf giant” ( Chamaegigas intrepidus ), various lilies such as the poison lily ( Ammocharis coronica ) or the candelabra lily , the red desert violet ( Sesuvium sesuvio ) and the zucchini morning star ( Tribulus zeyheri ) belonging to the root thorns .

The official botanist of German South West Africa , Kurt Dinter , had already recognized a "magnificent shrub" near Ameib in the Erongo Mountains in 1909 as the Strophanthus amboensis , which belongs to the poison family . Adolf Engler , the leading plant expert of his time, described the Erongoberge as “quite rich in woody plants” and mentioned the plants and other plants mentioned above. a. the mulberry fig ( Ficus damarensis , today Ficus sycomorus ), the lavender bush ( Croton gratissimus ), the wild pear ( Dombeya rotundifolia ), the kudu bush ( Combretum apiculatum ), the medlar ( Vangueria infausta ) and Acacia caffra ) ra (today synonymous with Senegueria ) and Peucedanum araliaceum (now synonymous with Steganotaenia araliacea ).

fauna

Due to the vegetation zones ranging from savannah to mountainous landscape, there is a diverse fauna. Particularly noteworthy is the occurrence of the black rhinoceros ( Diceros bicornis ), more precisely that of one of the two subspecies found in Africa, the Diceros bicornis bicornis . The occurrence of the black-nosed impala ( Aepyceros petersi ), a medium-sized herding antelope, whose occurrence is limited to northwestern Namibia and southwestern Angola, is also exceptional . Thanks to the efforts of the Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary, it was able to be reintroduced, which means that today the Erongo Mountains have the largest free-living population of this impala species outside of the Etosha National Park.

African elephants have been migrating from neighboring Damaraland to the Erongo region since 2006 . After initially individual or groups of bulls were sighted in the Erongo, a small herd has now established itself in the northwest of the area. There are good populations in the Erongo for the endemic Hartmann's mountain zebra ( Equus zebra hartmannae ). The frugal animals usually stand in small family groups of up to eight animals on the steep slopes or on rocky knolls and move down into the valleys to graze in the evening. The tiny Damara Dik-Dik , an endemic antelope species, can be found mainly in the thickest undergrowth of the gallery forests along the Riviere or in thorn bushes.

Zambezi greater kudu and gauntlet are widespread , and eland , leopard , warthog and Kalahari springbok are also found. The rocky mountains are the ideal habitat for Angola klipspringer and along the rivers and in the valleys you can also see ibex and crown duiker. While the eland occurs only in the more lush northeast of the area, giraffes can also be found in very good populations in the barren south and west of the Erongo Mountains and its foothills. Baboons , which can also colonize the gallery forests along the Riviere in larger groups, can often be heard earlier than seen due to their morning communication. Furthermore, the occurrence of aardwolf , cheetah , hyena and white-tailed wildebeest is mentioned. It is also worth taking a look at the smaller mammals. A specialty is the curious black mongoose ( Galerella nigrata ), an endemic subspecies of the rotichneumon, which occurs in very high numbers in the granite areas of the Erongo. Furthermore come Kaokoveld slender mongoose ( Galerella flavescens ), gophers, wild cats, lynx and genet before. The rare Cape fox ( Vulpes chama ) and spoonhounds can also be found here.

Last but not least, there is a very rich bird world in the Erongo Mountains with, for example, the African ostrich , the gray noise bird ( Corythaixoides concolor ), the Namib flycatcher ( Namibornis herero ) and various weaver birds such as B. the mask weaver ( Ploceus velatus ). The seven endemic bird species found here include u. a. the hard- leaved frankolin ( Francolinus hartlaubi ), the thrush-shrike ( Lanioturdus torquatus ), the Monteiro toko ( Tockus monteiri ) or the Damara rock diver ( Achaetops pycnopygius ). On the other hand, a number of interesting migratory and water birds can be observed seasonally in the Erongo, such as the Abdim stork ( Ciconia abdimii ) on the Ameib farm in January 2006 . In addition, there are a variety of reptile species, such as the rock dragon ( Agama atra ), the python or the African spitting cobra as well as other agamas , real lizards , geckos , scorpions , spiders and beetles .

Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust

The forerunner of the "Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust" of Namibia was the "Erongo Mountain Nature Conservancy" founded in 2000, the main goal of which was to reintroduce the black rhinoceros. In 1972 the last black rhino was caught for fear of poachers and moved to a national park . With the establishment of the Erongo Mountain Nature Conservancy, an area was to be created in accordance with government specifications, which would enable resettlement on private farmland - a process with which the Namibian government has already achieved success elsewhere. In order to set themselves apart from the numerous other conservancies - but primarily to ensure the sustainability of nature conservation - the farm owners in question decided to go further and founded the Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust of Namibia in 2009. The crucial difference was that the entry of a farm owner inevitably goes hand in hand with a change in the land register. The land is irrevocably added to the trust area. This ensures sustainability regardless of a change of ownership or generation. In 2013, the Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust of Namibia eV charity with its headquarters in Bielefeld was founded to provide financial support.

The Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust of Namibia clearly formulates its objectives in its statutes of 2009. Following the ethical teachings of nature conservation, a private nature reserve is to be created through which nature and species protection can be guaranteed in the long term. This is decisive for one of the primary goals of the trust: The permission for the settlement and long-term accommodation of the endangered black rhinos by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism of Namibia. In order to let the game go its natural way, all fences should be removed. Endemic species are to be reintroduced and endangered species are to be conserved and reproduced so that a stable population is ensured and relocation to other areas can follow. The Erongo Mountains should be preserved in their special geomorphology and used for educational, scientific and touristic purposes. The aim here is to prevent any use that is detrimental to the actual purpose of the area and to remove non-native animal and plant life from the area. Furthermore, as a contribution to the upswing in Namibia, long-term jobs are being created for the local population. This cooperation should result in an optimally utilized, cost-effective and functional nature conservation company that is free from corruption and abuse and can be managed with discipline. Taking into account the ethics of nature conservation, it is the responsibility of the farm owners to prevent an excess of wildlife through appropriate hunting. All of the above principles are intended to contribute to the promotion of nature conservation in Namibia and the rest of the regions of southern Africa, arouse national and international interest as well as show responsibility and encourage implementation.

economy

Agriculture and tourism

There is not much left of the livestock farming practiced for over a century on the farms in the Erongo Mountains. So was z. B. on farm Ameib 60 gave up cattle husbandry at the beginning of the 1990s. Many farms are now operated as guest farms ( lodges ) or as hunting farms, which make an important contribution to tourism. Today the Erongo Mountains are best known for the grandiose nature that emerges from the weathering of the Erongo granite and led to the famous rock castles and monument landscapes (e.g. Bull's Party and elephant head formation). There are opportunities for hiking and rock climbing in particular in the area of the farms Omandumba West and Anibib and in the area of the farms Ameib and Nieuwoudt.

In the early 1990s, Hubert Herzog built the first commercial bottling plant for mineral water on the Otjompaue-West farm near Omaruru on the Erongo , which continues to supply large parts of the Namibian market with mineral water that also meets the criteria of the German mineral and table water ordinance . Although Namibia is one of the smallest wine-growing areas in the world due to the extreme climatic conditions, the Omaruru wine-growing area, which is the oldest wine-growing area in Namibia and home to the country's first winery, makes a significant contribution to wine-growing in Namibia .

Mining

From 1910, when the tin ore deposits were discovered on the Ameib farm, mining for rare metals such as tin , tungsten , lithium , niobium and tantalum was carried out in the vicinity of the Erongo Mountains , and cassiterite and / or ferrotantalite , amblygonite and lepidolite in pegmatite deposits promoted. These deposits include the Sidney, Borna and Carsie pegmatites and the Davib Mine on the Davib East 61 farm area; the Ameib pegmatite on Ameib 60, the Drews pegmatite on Kudubis 19, the Brabant pegmatite on Brabant 68 as well as Pietershill, the Elliot Claims, Schimanski's Claims and Wendroth's Workings on Erongurus 166. The tin ore continued to be mined on the pegmatites mentioned until in the 1930s. In April 1939, however, all activities were suspended. The "Krantzberg Tungsten Mine" on the Krantzberg near Omaruru, which was one of the most important tungsten producers in southern Africa, has been idle since 1980.

- Ore minerals

Cassiterite ( tin stone )

Ilmenite ( titanium iron )

Siderite ( iron spar )

Since the spring of 1999, when steps with well-crystallized schörl and topaz were first found in Miarolen in the Erongo granite, small-scale miners have been mining them on mineral steps for the collector's market. The best-known minerals from the miaroles in the Erongo granite are beryl in the varieties aquamarine and goshenite, schörl , potassium feldspar , quartz and its varieties smoky quartz , muscovite , fluorite , hydroxyl herderite , topaz , cassiterite and jeremejewite . In this artisanal mining, where mining work is only done manually, accidents with sometimes fatal results are not uncommon due to the low safety standards in the rival small businesses.

- Jewelry minerals and collector's items

Aquamarine (blue) and Schörl (black)

Colorless beryl ( goshenite ) with hyalite ( common opal , white)

Quartz and smoky quartz

annotation

- ↑ Note: This article contains characters from the alphabet of the Khoisan languages spoken in southern Africa . The display contains characters of the click letters ǀ , ǁ , ǂ and ǃ . For more information on the pronunciation of long or nasal vowels or certain clicks , see e.g. B. under Khoekhoegowab .

See also

literature

- Anonymous: Excursion report of the wild biological excursion in the Erongo, Namibia . 1st edition. Institute for Wildlife Research at the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Hannover 2005.

- Phoebe Barnard: Biological Diversity in Namibia: a Country Study . 1st edition. ABCpress, Capetown 1998, ISBN 0-86976-436-5 , pp. 1-325 .

- Ludi van Bezing, Rainer Bode, Steffen Jahn: Namibia: Minerals and Localities I . 1st edition. Bode-Verlag GmbH, Salzhemmendorf 2014, ISBN 978-3-942588-13-3 , p. 1-607 .

- Wolf Dieter Blümel, Rolf Emmermann, Klaus Hüser: The Erongo: Geoscientific description and interpretation of a south-west African volcanic complex (scientific research in south-west Africa, 16th episode) . 1st edition. Publisher of the SWA Scientific Society, Windhoek 1979, ISBN 0-949995-31-2 , p. 1-140 .

- Hans Cloos: Geology of the Erongo in Hererolande: Geological observations in South Africa, part II (contributions to the geological research of the German protected areas, volume 3) . 1st edition. Royal Prussian Geological State Institute (publisher), Berlin 1919, p. 1-84 .

- Hans Cloos: The Erongo: A volcanic massif in the table mountains of the Hereroland and its significance for the spatial question of plutonic masses (contributions to the geological research of the German protected areas, issue 17) . 1st edition. Geological Central Agency for the German Protected Areas (publisher), Berlin 1919, p. 1-238 .

- Hans Cloos: Conversation with the earth: geological trip around the world and life . 1st edition. Book guild Gutenberg, Frankfurt aM 1947, p. 1-389 .

- Barbara Curtis, Coleen Mannheimer: Tree Atlas of Namibia . 9th edition. National Botanical Research Institute and Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry, Windhoek 2005, ISBN 99916-68-06-3 , pp. 1-674 .

- Nicole Grünert: Namibia's Fascinating Geology - A Travel Guide . 3. Edition. Klaus Hess Verlag, Göttingen / Windhoek 2005, ISBN 3-933117-13-5 , p. 1-198 .

- Klaus Hüser: Namibrand and Erongo: on the geomorphology of two south-west African landscapes (Karlsruhe geographical booklet No. 9) . 1st edition. Geographical Institute of the University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe 1977, p. 1-214 .

- Hannah Schreckenbach: Traces of life in sand and rock: The story of Ameib . 1st edition. Namibiana Book Depot, Delmenhorst 2009, ISBN 978-3-936858-97-6 , p. 1-108 .

Web links

- Flora on Eileen Farm in Northeast Erongo

- Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust - Non-profit society for the protection of the Erongo Mountains

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andrew Goudie, Heather Viles: Landscapes and Landforms of Namibia . 1st edition. Springer, Dordrecht 2015, ISBN 978-94-017-8019-3 , pp. 85-89 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-94-017-8020-9 .

- ↑ a b c Hans Cloos : The Erongo: A volcanic massif in the table mountains of the Hereroland and its importance for the spatial question of plutonic masses (contributions to the geological research of the German protected areas, issue 17) . 1st edition. Geological Central Agency for the German Protected Areas (publisher), Berlin 1919, p. 1-238 .

- ↑ a b c Marcus Wigand, Axel K. Schmitt, Robert B. Trumbull, Igor M. Villa, Rolf Emmermann: Short-lived magmatic activity in an anorogenic subvolcanic complex: 40 Ar / 39 Ar and ion microprobe U-Pb zircon dating of the Erongo, Damaraland, Namibia . In: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research . tape 130 , 2004, pp. 285-305 , doi : 10.1016 / S0377-0273 (03) 00310-X .

- ↑ a b c d Wolf Dieter Blümel , Rolf Emmermann , Klaus Hüser: The Erongo: Geoscientific description and interpretation of a south-west African volcanic complex (4. The current shape of the mountains (morphography)) . 1st edition. Publisher of the SWA Scientific Society, Windhoek 1979, ISBN 0-949995-31-2 , p. 63-78 .

- ^ Andrew P. Boudreaux: Mineralogy and geochemistry of the Erongo Granite and interior quartz-tourmaline orbicules and NYF-type miarolitic pegmatites, Namibia (University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1854) . PhD thesis. University of New Orleans, New Orleans 2014, pp. 1-246 .

- ↑ Republic Namibia Directorate of Surving and Mapping (Ed.): Namibia 1: 250 000 sheet 2114 Omaruru . 3. Edition. Directorate of Surving and Mapping, Windhoek 2003.

- ↑ Chief Director of Surveys and Mapping (Ed.): Southern Africa 1: 500 000 sheet 2113 Windhoek . 1st edition. Government Printer, Pretoria 1984.

- ↑ a b c d e Hannah Schreckenbach: Traces of life in sand and rock: The story of Ameib . 1st edition. Namibiana Book Depot, Delmenhorst 2009, ISBN 978-3-936858-97-6 , p. 1-108 .

- ↑ a b c Wolf Dieter Blümel , Rolf Emmermann , Klaus Hüser: The Erongo: Geoscientific description and interpretation of a south-west African volcanic complex (2nd structure and formation of the Erongo complex) . 1st edition. Publisher of the SWA Scientific Society, Windhoek 1979, ISBN 0-949995-31-2 , p. 16-53 .

- ↑ Gabi Schneider, Thomas Becker, Ludi von Bezing, Rolf Emmermann, Steven Frindt, Dougal Jerram, John Kandara, Paul Keller, John Kinahan, Jürgen Kirchner: The roadside geology of Namibia (collection of geological guides; 97) . 2nd Edition. Borntraeger, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-443-15084-6 , p. 1-294 .

- ^ A b c d e f Franco Pirajno: Geology, geochemistry and mineralization of the Erongo Volcanic Complex, Namibia . In: South African Journal of Geology . 93 (Issue 3), 1990, pp. 485-504 .

- ↑ Marcus Oliver Wigand: Geochemistry and Geochronology of the Erongo Complex, Namibia . PhD thesis. Mathematical and Natural Science Faculty of the University of Potsdam, Potsdam 2003, p. 1-99 + I-LXXIV .

- ↑ Discovery of the Phillips Cave

- ↑ a b Phillips Cave

- ^ Andreas Vogt: National Monuments in Namibia . 1st edition. Gamsberg Macmillan Publishers (Pty) Ltd, Windhoek 2004, ISBN 3-443-15084-5 , pp. 1-294 .

- ↑ a b Paula Cave

- ^ A b Ernst Rudolf Scherz: South West Africa: Annual Reports 1962–1979 Namibia . exp. New edition edition. Basler Afrika Bibliogr., Basel 2004, ISBN 3-905141-83-3 , pp. 1-149 .

- ↑ a b Jürgen Richter: Under the sign of the giraffe: collector - hunter - painter in Namibia . In: Archeology in Germany . 1989 (issue 2), 1989, pp. 38-41 .

- ↑ People and Culture - Agriculture in Namibia

- ↑ Hans Cloos : Geology of the Erongo in Hererolande: Geological observations in South Africa, Part II (Contributions to the geological research of the German protected areas, Volume 3) . 1st edition. Royal Prussian Geological State Institute (publisher), Berlin 1919, p. 1-84 .

- ↑ Hans Cloos : Conversation with the earth: geological journey around the world and life . 1st edition. Book guild Gutenberg, Frankfurt aM 1947, p. 1-389 .

- ↑ Wolf Dieter Blümel , Rolf Emmermann , Klaus Hüser: The Erongo: Geoscientific description and interpretation of a south-west African volcanic complex (3. The climatic equipment) . 1st edition. Publisher of the SWA Scientific Society, Windhoek 1979, ISBN 0-949995-31-2 , p. 54-62 .

- ^ A b Barbara Curtis, Coleen Mannheimer: Tree Atlas of Namibia . 9th edition. National Botanical Research Institute and Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry, Windhoek 2005, ISBN 99916-68-06-3 , pp. 1-674 .

- ↑ a b Patricia Craven, Christine Marais: Damaraland Flora Spitzkoppe Brandberg Twyfelfontein . 1st edition. Gamsberg Macmillan Publ., Windhoek 1993, ISBN 0-86848-824-0 , pp. 1-127 .

- ↑ Flora on Eileen Farm in northeast Erongo

- ↑ Kurt Dinter: German South-West Africa: Flora, forest and agricultural fragments . 1st edition. Theodor Oswald Weigel, Leipzig 1909, p. 109 .

- ↑ Adolf Engler: The flora of Africa, especially its tropical areas: Basic features of the plant distribution in Africa and the character plants of Africa . 1st edition. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1910, p. 577 .

- ↑ a b Robin Frandsen: Mammals of Southern Africa - A determination manual . 9th edition. Honeyguide Publications CC, Forways 2002, p. 1-215 .

- ↑ a b c d Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust - Non-profit society for the protection of the Erongo Mountains

- ↑ Nicole Grünert: Namibia's Fascinating Geology - A Travel Guide . 3. Edition. Klaus Hess Verlag, Göttingen / Windhoek 2005, ISBN 3-933117-13-5 , p. 1-198 .

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung, article «Bottled water in competition» from May 19, 2005 by Anonymus

- ↑ Wineries in Namibia

- ^ Percy A. Wagner: The geology and mineral industry of South-West Africa . In: Geological Survey South Africa Memoir . tape 7 , 1916, pp. 112 .

- ↑ a b Herbert F. Frommurze, Traugott Wilhelm Gevers , PJ Rossouw: The geology and mineral deposits of the Karibib area: An Explanation of Sheet No. 79 (Karibib, SWA) . 1st edition. Union of South Africa Department of Mines Geological Survey of South West Africa, Pretoria 1942, p. 1-180 .

- ^ Sidney Henry Haughton, Herbert F. Frommurze, Traugott Wilhelm Gevers , CM Schwellnuss, PJ Rossouw: The geology and mineral deposits of the Omaruru area: An Explanation of Sheet No. 71 (Omaruru, SWA) . 1st edition. Union of South Africa Department of Mines Geological Survey of South West Africa, Pretoria 1939, p. 1-160 .

- ↑ Steffen Jahn, Reinhard Bast: The Krantzberg near Omaruru, Namibia, and the mineral deposits in its vicinity . In: Mineral World . 17 (Issue 3), 2006, pp. 32-48 .

- ^ A b Bruce Cairncross, Uli Bahmann: Famous Mineral Localities: The Erongo Mountains Namibia . In: The Mineralogical Record . tape 37 , 2006, p. 361-470 .

- ↑ a b Ludi van Bezing, Rainer Bode, Steffen Jahn: Namibia: Minerals and Localities I . 1st edition. Bode-Verlag GmbH, Salzhemmendorf 2014, ISBN 978-3-942588-13-3 , p. 1-607 .