Brandberg massif

| Brandberg | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Brandberg massif seen from the south |

||

| Highest peak | Koenigstein ( 2573 m ) | |

| location | Erongo , Namibia , Southern Africa | |

|

|

||

| Coordinates | 21 ° 7 ′ S , 14 ° 33 ′ E | |

| Type | Single solid | |

| rock | granitic plutonites | |

| Age of the rock | 132–130 million years | |

| surface | 420 km² | |

| particularities | First ascent of the Königstein on January 2, 1918 by Reinhard Maack | |

The Brandberg massif (often just Brandberg ; khoekhoegowab Dâures , otjiherero Omukuruvaro ) is a mountain massif in Damaraland in Namibia . It is located in the Erongo region in the west of the country, around 90 km from the Atlantic Ocean, has an average height of 2500 m and towers over the surrounding country by almost 2000 m . His and at the same time Namibia's highest mountain is the Königstein with a height of 2573 m . The Zisabspitze ( 2228 m ) on the eastern edge of the Brandberg massif also has an exposed location . The entire elevation is oval and covers an area of 420 km² .

"Except for being a haven for photographers, mountaineers and archaeologists the Brandberg also attracts botanists and zoologists, drawn by the huge diversity in plant and animal life in the area."

"The Brandberg is not only a paradise for photographers, mountaineers and archaeologists - it also inspires botanists and zoologists, who are attracted by the enormous diversity of plant and animal life in this area."

Surname

Early mentions of the Brandberg and its inhabitants come from the 19th century. B. by Charles John Andersson and Georg Gürich . The report by a "Capitain Messum" quoted by Charles John Andersson is likely to be one of the first mentions of today's Brandberg. According to Captain Messum, the mountain, which the locals called "Dourissa", was named "Messum Mountain" or "Mount Messum" by its discoverer. The mountain is also shown on a map published in 1856, at an estimated elevation of 3,200 feet above sea level. The name has not been able to prevail, but the name of Capitain Messum lives on in the name of the 45 km southwest of the "Messum Crater".

On a map of German South West Africa in the Langhans Colonial Atlas published in 1894 , the Brandberg massif appears with three different names: “Brandberg”, “Daureb” and “Omukuruwaro”.

The official name Brandberg, which is still in use today, comes from the glowing color in which the mountain appears when the sun shines on it from the west . The Khoisan ( Khoekhoegowab ) -speaking Damara , whose settlement area has always included the Brandberg, call it Daureb , Daunas or Daures , which translates as “burned mountain”, “because the land there is so bare and without grass or trees, as if it would have burned down (daú) " The Bantu ( Otjiherero ) speaking Herero , who came from the Kaokoveld and invaded Damaraland since the middle of the 18th century, refer to the Brandberg as Omukuruwaro (mountain of the gods) or the land / area of the ancestors .

In recent specialist literature it is referred to as Dâures Mountain .

First ascent

February 1914: The surveyors Claus Burfeindt and Hans Carstensen , both members of the colonial protection force , climbed into the Brandberg massif with great difficulty and only with the support of individual people on site.

“At noon on the second day they gained an overview of the whole mountain range, with its various peaks. Without having binoculars the further direction had to be determined in order to climb the highest point (...) until they reached the summit on the third day. (...) Then work began. The TP had to be determined, at the highest point a bolt that had been carried in the luggage was cemented in. The signal connection with Okombahe was established with the heliograph , which Burfeindt had to maintain until he received further commands. "

The two were wrong about the highest peak: it only turned out much later (1955) that they were on the Horn , the second highest peak of the Brandberg, because the iron rod cemented by Burfeindt was found on the Horn (2519 m) ( see the illustration opposite).

“At the beginning of January 1955, the surveyor Mendes-de-Gouvêa, Windhoek, carried out the survey of the highest peak of the Brandberg, Königstein (2573 meters) on behalf of the administration. The ascent took place over the Baswald channel; Mendes-de-Gouvea was accompanied and supported in this work by the well-known mountaineers Albert Jagdhuber and Franz Baswald, who had made themselves available to him as guides. The Baswald Rinne was named after the Austrian Franz Baswald (born 1928). "

The actual first ascent of the Königstein in the Brandberg massif was made by Ernst August Gries , Reinhard Maack and Georg Schulze on January 2nd, 1918. While descending, Maack discovered the famous “ White Lady ” on January 4th . On the occasion of the centenary of the first ascent, a small group from Germany including the political scientist Helge Kleifeld, the archaeologist Martina Trognitz and the pilot Lukas Gehring led by the Namibians John Dungle, Cohlen Gawanab and Michael Taniseb over the Gaseb on January 1, 2018 - Climbed the gorge on the south side of the Brandberg.

A map of the Brandberg, which was made based on the photogrammetric recordings made by Reinhard Maack and Albert Hofmann in 1917/18 on a scale of 1: 200,000, is among others. a. to be found in the annex to Jana Moser's dissertation.

geography

The Brandberg lies between 21 ° to 21 ° 15 'south latitude and 14 ° 25' and 14 ° 40 'east longitude and is located 80–90 km from Cape Cross and the Atlantic coast. Over an area of about 420 km² (according to other information 750 km²) it forms a slightly oval massif of 26 × 21 km extension and a mean diameter of 23 km, which on average towers over its surroundings by almost 2,000 m and which is the most prominent elevation in represents the central Namib . The massif is still visible from a distance of over 100 km on a clear day. The next place is the former mining settlement of Uis, about 30 km from the Brandberg .

The four highest peaks of Namibia are all in the Brandberg massif: "Königstein" ( 2573 m ), " Horn " (or "Claus-Burfeindt-Horn") ( 2519 m ), " Numasfels " ( 2518 m ), " Aigub " ( 2501 m ) m ) as well as the " Orabes-Kopf " ( 2299 m ) and the " Zisabspitze " (also "Tsisabspitze") ( 2228 m ). On the official map of Namibia 1: 250,000 sheet 2114 Omaruru, the heights differ slightly from the figures given here. Due to the low notch height and the dominance , however, these are not independent peaks, but rather subsidiary peaks of the Königstein in one and the same massif.

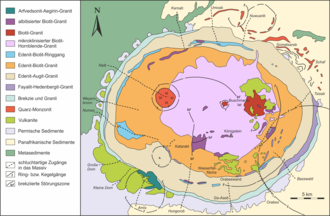

The Brandberg massif is crossed radially by around 20 main drainage systems, with deep gorges extending into the massif around the Brandberg (compare the map on the right). Starting from the east, clockwise these are the gorges "Tsisab", "Basswald", "Orabes", "Ga-Aseb" (or "Gaseb"), "Hungorob", "Amis", "Small Cathedral", "Great Cathedral" "," Numas "," Weilersbronn "," Naib "," Karoab "," Umoab "," Nuwoarib "," Sonusib "and" Schaf ". The largest of these canyons are Numas and Naib in the west and Tsisab in the east. There are no continuous water-bearing rivers in the Brandberg massif and its immediate surroundings. At best temporary water flow is only recorded in the case of occasional falling precipitation, when the rivers, called Riviere in this region , “come off”. The Ugab flows north of the Brandberg , to which all the rivers, including the Amis, drain the east, north and west of the Brandberg massif. The rivers that drain the southern part of the Brandberg flow into the Messum and Orawab .

Summit of the Königstein

geology

The pluton of the Brandberg massif or the Brandberg complex is a granite intrusion and represents an anorogenic ring complex of the intraplate type, which took place in the earth's crust about 130 million years ago in the geological epoch in the Jura and in the chalk at a high crustal level. 40 Ar / 39 Ar age determinations resulted in an age of 132-130 million years, which shows that the various granitic units of the Brandberg are indistinguishable from one another in terms of age and that they coexist with the flood basalts and the associated felsic volcanism of the Etendeka - Paraná province have formed. The uplift and removal of about 5 km of overlying rock happened about 60–80 million years ago.

The Brandberg aroused the interest of many geologists , mineralogists and petrographers as early as the first half of the 20th century , and later also of geophysicists , chemists , geochemists and physical chemists . Hans Cloos and Karl F. Chudoba dealt with the construction, formation and shape of the Brandberg massif, and Hermann Korn and Henno Martin with its intrusion mechanism . Later, Frank DI Hodgson dealt with petrography and evolution of the Brandberg intrusion. Oleg von Knorring, J. Potgieter, C. Schlag and Alexander Willgallis, Axel Schmitt et al. And Franco Pirajno discussed the economic potential of the mineralization in the Brandberg massif.

The most important publications on the rocks of the Brandberg complex include Michael Diehl's dissertation on the geology, mineralogy, geochemistry and hydrothermal alteration of the Brandberg and the work of Peter Bowden and co-workers on the evolution of anorogenic granites in Namibia. Age dating on the rocks of the Brandberg took u. a. Ronald T. Watkins and coworkers and Axel K. Schmitt and coworkers above. Among the more recent works, those by Matthias J. Raab and colleagues and Tim Vietor and colleagues must also be mentioned.

construction

At the current level of erosion, the complex shows a number of sub-volcanic igneous centers, all of which are granitic in composition. Metalumic granites and quartz-monzonitic rocks took their place as ring ducts or cone sheets outside the later caldera or as thick, ring-shaped layers. Peralum granites occupy the central part of the complex; chronologically they are followed by peralkaline granites on the periphery of the massif. All rock types of the Brandberg Complex show significant mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of granites with high heat production (high-heat-producing granites ) or A-type granites with abnormally high contents of incompatible elements . These include elements with high field strength (high field strength elements , e.g. Zr , U , Th , Nb or Ta ) and LILE (large-ion lithophile elements, i.e. elements with a large ionic radius such as K , Rb , Cs , Sr or Ba ).

Different types of postmagmatic hydrothermal alteration processes have been observed that are similar to those associated with anorogenic ring complexes in Nigeria . Depending on the original chemical composition of the crystallizing granite and the hydrothermal fluids that trigger metasomatic processes , processes of potassium metasomatosis, sodium metasomatosis, aging , tourmalinisation and chloritisation can be observed. Cation exchange processes led to the collapse of the primary mineral association in the granites and to the generation of hydrothermal mineral parageneses , which were associated locally with the crystallization of zinc , tin , niobium, yttrium and REE -containing ore minerals . Is the spectrum of subsolidus-minerals in these Socialization characterized by the presence of albite (From 99.4 to 96.8 to 0.6 to 3.2 ), flushed Mikroklin , the destabilization of frühkristallisiertem biotite favor of mica of Siderophyllit - Zinnwaldite Series as well as local concentrations of tourmaline .

Fenitized granites, which contain hydrothermally formed zinc-bearing fluorine - arfvedsonite and tin-bearing aegirine as newly formed minerals, occur in layered, agpaitic rock series of the Amis complex, a satellite intrusion on the southwestern edge of the Brandberg. In this context, different types and styles of mineralization occur: disperse Nb-, Ta-, REE-mineralization, finely distributed Sn-mineralization as well as fissure- and vein-controlled sulphide / oxide mineralization (Zn / Sn). Mineralizations in the Brandberg Complex are generally restricted to zones where postmagmatic fluid-rock interaction processes took place, the duration and intensity of which were long enough or large enough to generate ore minerals. Alteration zones were observed in the roof areas of the complex, along the contacts and the edge areas of the individual intrusions as well as in the surrounding rock.

Emergence

The Brandberg shows a magmatic evolution similar to that of other granitic alkali rock ring complexes. The formation of the “Brandberg Alkaline Complex” traditionally began with a doming of the earth's crust, which led to the formation of cone gaps and which was followed by the placement of cone sheets . The earliest volcanic activity probably began with pyroclastic products and pyroclastic flows of rhyodacite composition. The pre-caldera stage of the complex was followed by a volcanic stage with violent eruptions of pyroclastic material and ignimbrites . As a result of the empty conveyance of the magma chamber , a burglary boiler was created , and there was also the extrusion of ignimbritic intra-caldera flows (caldera stage). With the beginning of the Plutonic stage, granitic magma was directed upwards, which solidified there in massive masses at higher levels. This stage was followed by subsidence and the intrusion of the next granitic magma pulse from the same magma chamber. The renewal of the domes led to the formation of a new center, which initially expressed itself in the formation of cone sheets of monzonite or monzogranite composition and ended with the placement of a central dome or a plug-like intrusion. The placement of alkali granites was followed by the peripheral intrusion of a laccolithic , perfectly stratified, peralkaline granite and socialized rock dikes . Finally, radial fractures were filled with olivine and quartz dolerites .

The various granites intruded in the following order, arranged from oldest to youngest unit:

- porphyry quartz monzonite ring dikes (approximate area 0.6 km²)

- Fayalite - Hedenbergite - Granite (15 km²)

- Edenite- Hedenbergite-Granite (220 km²), also known as "Core Granite" or "Main Granite"

- central hornblende biotite granite, partly microclinized (210 km²)

- Biotite granite (24 km²)

- Quartz monzonite (7 km²)

- peralkaline, agpaitic arfvedsonite-aegirine-granite (5.5 km²), also called brandbergite .

Several mighty clods of Etendeka- period quartz latites and basalts as well as Karoo-period sediments, which form a border around the base of the massif at 800–900 m above sea level, can also be found in the eastern part of the Brandberg at greater heights (2200 m). They were torn up with the intruding granitic, highly viscous post-Etendeka magma.

history

During the investigation of the settlement-technical stages of the Brandberg, cultural layers from the Middle Stone Age were found in the Amis Gorge in two rock roofs , which prove that the Brandberg was at least visited at this early time, which also agrees with the idea that in the Middle Stone Age in contrast to the Early Stone Age more and more new habitats and resources were developed. The frequency and regularity of traces from the younger Later Stone Age (from the 6th century BC ) to the turn of the times indicate a heyday in the settlement of the Brandberg massif. From the turn of the times, the traces of settlement in the Brandberg decline sharply, without any precise reasons being known. Only from around 1500, i.e. in the last 500 years, did the traces of settlement, which are summarized as "Brandberg culture", increase again sharply. The changes that occurred during the colonial era in the early 20th century probably led to the abandonment of the Brandberg as a settlement area. The reasons for choosing the Brandberg as a long-term or temporary living space may have been different for the occupied settlement phases. The diverse natural resources of the Brandberg massif, which stand in striking contrast to the desert-like environment and which, in view of the relatively constant climatic and environmental conditions in the Young Pleistocene and Holocene, were present for the entire duration of its human settlement, always represented a constant factor. They were certainly one the main reasons for the temporary or long-term settlement of the mountain range.

Rock art

The Brandberg is known as the " Louvre of rock painting". Around 50,000 rock paintings have been found at 1,000 sites on the Brandberg to date - mostly on overhangs and in inaccessible terrain. This large number indicates a great abundance of animals in the past. The best known of these works of art is about 45 cm White Lady (White Lady), which on January 4, 1918 by Reinhard Maack was discovered in the Tsisab Gorge and is one of the finest prehistoric rock paintings.

In addition to this presumed warrior, who can also be interpreted as a shaman, numerous other hunters with spears or bows can be seen. These are surrounded by typical game such as B. Oryx antelopes and zebras . The age of the drawings is estimated to be two to four thousand years. It is not clear whether these are just hunting scenes to conjure up hunting luck or trance dances by shamans who heal with the help of spirits in animal form.

Many of the paintings were smeared and destroyed by mass tourism, and the famous lady was protected by bars in the meantime. To prevent further vandalism, a guide must be taken for the one and a half to two hour hike (complete, there and back).

The site with the richest rock art in the entire Brandberg massif is the “Amis 10” ( giant cave ) roof in the upper Amis Gorge , where over 1,000 rock paintings have been counted. This place is characterized by its protected location, the large covered area and the pleasant microclimate as an unusually favorable place to stay.

The drawings were largely documented by Harald Pager from the University of Cologne (“The Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg I – V”). Up until his death in 1985 , in eight years he recorded around 43,000 drawings of 879 rock art sites on 6 km of plastic film.

There are other rock paintings and petroglyphs . a. at the Spitzkoppe and in Twyfelfontein .

climate

According to Paul van den Elzen, the Brandberg has a tropical, episodic-periodic summer humid semi-desert to dry savanna climate. Rain falls mainly between January and March with easterly winds, mostly in the form of thunderstorms. The average annual precipitation is 50–100 mm near the peaks and 15–30 mm at the edge of the massif. The main wind direction is southwest, which means that moisture from the Atlantic enters the Brandberg area. The irregular appearance of fog is characteristic. In summer the temperatures fluctuate between 31 ° C and 35 ° C with a nighttime minimum of 15 ° C. The heat radiation of the heated rock can result in local microclimates with significantly higher temperatures. This is also the reason why the surrounding plain cools down significantly more at night than the granite massif.

| the Brandberg massif | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Monthly average temperatures and precipitation for the Brandberg massif

Source:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The climate classification of Köppen and Geiger , according to the climate in the Brandberg area type BWh - so it prevails desert climate with year-round little rainfall . The weather data mentioned below is based on values that Harald Pager collected on 1354 days between October 1977 and May 1985.

The warmest months in the Brandberg massif are December, January and February. In the eight-year observation period mentioned, the mean values for these months were over 30 ° C, the minimum values between 17 ° C and 20 ° C. The highest temperature ever was measured in the Karoab Gorge at 43 ° C. From March the temperatures drop and in June are a minimum of 12.5 ° C and a maximum of 22.5 ° C. From July there is a gradual increase in temperature. Even in the winter months, temperatures rarely drop below 10 ° C. However, ice layers up to 1 cm thick have been observed at water points, so that temperatures below freezing point also occur.

Precipitation falls mainly in the summer months from January to March. In the eight years of detailed precipitation measurement, the monthly mean precipitation was 15–20 mm. With the exception of June and July, precipitation decreases sharply from April to October and only increases again to values below 10 mm in the "small rainy season" in November and December. The amounts of rain that fell during the observation period in June and July are exceptionally high for the winter months and are probably due to storm foothills in the Cape's winter rain zone reaching far north.

The amount of annual precipitation turns out to be extremely variable. From 1978 to 1980 the amount of precipitation fell from 60 mm to 35 mm and in 1981 to almost 0 mm. In the following four years the annual rainfall reached values between 90 and 110 mm. The annual mean over the years 1978–1985 is 67 mm. Nationwide, this period was referred to as low-rainfall, so that under normal conditions in the long term, around 100 mm of precipitation can be expected. This would also correspond to the location of the Brandberg in the western part of the zone with annual precipitation of 100–200 mm. The highest amounts of precipitation were measured in the gorges in the west and north of the massif, but this is more due to the fact that H. Pager stayed in the southern and eastern part of the Brandberg massif rather rarely and then only in the dry season.

ecology

flora

According to Johan Wilhelm Heinrich Giess , the Brandberg is located on the border between the zone of the central Namib and the semi-desert and savannah transition zone to the east, in which increasing amounts of precipitation allow for lush vegetation. The picture here is mainly shaped by species that are large in relation to the Namib flora. These include Gürich's milkweed ( Euphorbia guerichiana ), various species of the genus Commiphora , the stem-succulent Cyphostemma species, Adenolobus garipensis and the acacia ( Acacia montis-ustii ) and Senegalia robynsiana . Within the semi-desert / savanna transition zone, the vegetation increases towards the east. The Brandberg is located in the west with little vegetation, which has only a few bushes and trees and where grass only thrives after sufficient rainfall. "With its abundance of vegetation, the mountains, which are surrounded by landscapes with little vegetation, have the character of an island that ventures into a botanically much poorer world."

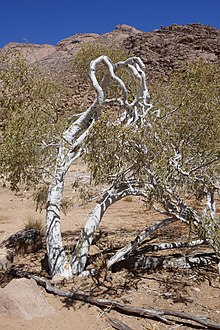

Overall, the flora of the Brandberg has been researched relatively thoroughly through the work of Willy Giess, Bertil Nordenstam , L. Moisel and Patricia Craven. Its biodiversity is considerable with around 500 different species. These include numerous small plants, but also shrubs, e.g. B. the already mentioned, frequently encountered Commiphora species such as blue-leaved commiphora or paper balsam tree ( C. glaucescens ), feather-leaved commiphora ( C. kraeuseliana ), rock myrrh or rock balsam tree ( C. saxicola ), rod- leaved commiphora ( C. virgata ) and Commiphora ( C. wildii ), and trees such as sycamore fig ( Ficus sycomorus ), shepherd tree or Witgatbaum ( Boscia albitrunca ) Sprokiesboom ( Moringa ovalifolia ), acacia species as faidherbia albida ( Faidherbia albida ) camelthorn ( Vachellia erioloba ), mountain mandrel ( Vachellia hereroensis ), Brandberg acacia, black bark tree or harpuisboom ( Ozoroa crassinervia ), butter tree ( Cyphostemma currorii ), Dombeya rotundifolia , stink trees such as Sterculia africana and S. quinqueloba and the quiver tree ( Aloe dichotoma ). The Namibian poison wolf milk ( Euphorbia virosa ), whose milky juice contains carcinogenic substances, occurs frequently . The desert cabbage ( Adenia pechuelii ) reaches gigantic proportions of sometimes more than 1 m in height in the Brandberg . The plant is widespread on the Namibrand and is otherwise counted among the small succulents together with Lithops ruschiorum and other small succulents. The origin of the rare tobacco species Nicotiana africana , which does not originate from the New World tobacco plants, is considered a phylogenetic and geographic mystery.

On the Brandberg the vegetation shows a strong gradient in height, whereby the species characteristic of regions with heavier rain become more prominent near the peaks. In the lower area of the slopes of the Brandberg massif, plants that are characteristic of the semi-desert and savanna transition zone appear . They include Moringa ovalifolia as well as the above-mentioned Adenolobus gariepensis and various species of the genus Commiphora . Brandberg acacia and Gürich's milkweed can be found both in the lower and middle areas of the slopes, whereas the butter tree is only found in the upper Brandberg massif. The gum arabic tree ( Senegalia senegal var. Rostata ) is bound to the presence of basalt . Species characteristic of the highland savannah (mountain thorn savanna) can be found in the upper Brandberg massif. They include mountain thorn, Euclea undulata , Dombeya rotundifolia , Rhus marlothii , black bark tree and olive tree ( Olea europaea subsp. Africana ). At the entrance to the gorges, bordering the Namib plain, or in watercourses at the base of the massif, there are species that are characteristic of the western river-tree savannah zone. B. camel thorn, ana tree, ancestral tree or lead tree ( Combretum imberbe ), the Tamarix usneoides belonging to the tamarisk , the false ebony tree ( Euclea pseudebenus ) and the toothbrush tree or lion bush ( Salvadora persica ) are to be expected.

There are seven endemic plant species in the Brandberg massif: Felicia gunillae (Asteraceae), Hermannia merxmuelleri (Sterculiaceae), Lithops gracilidelineata subsp. brandbergensis (Mesembryanthemaceae), Nidorella nordenstamii (Asteraceae), Pentzia tomentosa (Asteraceae), Plumbago wissii (Plumbaginaceae) and Ruellia brandbergensis (Acanthaceae). Of these seven plants endemic to the Brandberg, three were only collected once in a year (1963) with unusually good rainfall. Two of these, Felicia gunillae and Pentzia tomentosa , were found near the summit of the Königsstein, while the herbaceous Nidorella nordenstamii was found on the west side of the Orabeswand in a dry watercourse. Plumbago wissii was recovered from the Königstein and the Aigub. The succulent plant Lithops gracilidelineata subsp. brandbergensis occurs between 2300 m and 2400 m and thus represents the highest ever encountered habitat for the genus Lithops . The two most common endemics are those that are also found in lower areas of the massif: Ruellia brandbergensis and Hermannia merxmuelleri . Hermannia merxmuelleri was originally only known from the Tsisab Gorge.

Some of the plants that Bertil Nordenstam identified as endemic to the Brandberg in 1974 have since been found in other areas of Namibia. These include Euphorbia monteiroi subsp. brandbergensis , frequent in the upper Brandberg plant that also at the Spitzkoppe is found Hoodia montana (synonymous with Hoodia currorii ), Mentha wissii (synonymous with in the Naukluft and south of the Orange River encountered Mentha longifolia subsp. Wissii), Scirpus aciformis (synonymous with Isolepis hemiuncialis ) and Scirpus hystricoides (synonymous with Lipocarpha rehmannii ). Othonna brandbergensis can also be found on Gamsberg . The Acacia montis-usti , named after the Brandberg, occurs only in Namibia, but is not endemic to the Brandberg.

fauna

"The animals of the Brandberg are less researched than the plants, which is surprising in view of the ecological peculiarity of the island world, which is outlined from a botanical point of view and which must also have an impact on the animal kingdom."

The largest animal in the Hohen Brandberg is the leopard ( Panthera pardus ), whose food in the Brandberg massif is likely to consist mainly of cliff jumpers, rock snakes and other small animals.

The the guinea pig resembling Klippschliefer ( Procavia capensis ) live in rocky shelters, in the vicinity thereof, the rock walls of a as Hyraceum designated solidified and bleached mass from the feces and urine of the animals are covered with white stripes, which well the dwelling of a Klippschliefer colony to make visible. It is possible that this white “hyraceum” was also used as a component of the white color for the rock paintings, as it is known for the faeces of birds of prey or hyena droppings. On the other hand, the influence of “Hyraceum” on the decay process of rock paintings is discussed.

The only occurring in Brandberg antelope is the Klipspringer ( Oreotragus oreotragus ), which is sedentary and usually occurs in pairs. Although not native to the Brandberg area, black rhinoceros ( Diceros bicornis ) and African elephants ( Loxodonta africana ) occasionally graze in the lower area of the gorges - recognizable by the dung left behind . a. Acacias are part of their diet.

Water holes attract birds that benefit from the insects that have not been recorded in their diversity. Various types of pigeon, rose parrots, toucans, owls, rock eagles and numerous small birds are mentioned. Guinea fowl and sand grouse have been observed in the gorges and their foothills. A more recent work lists 120 different bird species for the Brandberg, six of which are described as common. Among them are laughing dove ( Spilopelia senegalensis , English Laughing dove ), Rosenköpfchen ( Agapornis roseicollis , English Rosy-faced lovebird ), Pycnonotus nigricans ( English African red-eyed bulbul ), mountain wheatear ( Oenanthe monticola , English Mountain Chat ) Onychognathus nabouroup ( English Pale-winged starling ) and Cinnyris fuscus ( English Dusky sunbird ).

Another 16 are mentioned as frequent. These include the the hawks belonging Falco rupicolus ( English rock Kestrel ) leading to the bustards scoring Eupodotis rueppellii ( English Rüppell's Korhaan ), rock pigeon ( Columba livia , English Rock Dove ), Namaqua Dove ( Oena capensis , English Namaqua Dove ), Perl -Sperlingskauz ( Glaucidium perlatum , english Pearl-spotted owlet ), Southern Gelbschnabeltoko ( Tockus leucomelas , english Southern yellow-billed Horn Bill ), Rotstirn Barbet ( Tricholaema leucomelas , english Acacia Pied Barbet ) of the swallows belonging Ptyonoprogne fuligula ( english skirt Martin ), Oenanthe familiaris ( English Familiar Chat ), Prinia flavicans ( english Black-chasted Prinia ), Batis pririt ( English Pririt Batis ), Southern fiscal shrike ( Lanius collaris , English Southern fiscal Shrike ) bokmakierie ( Telophorus zeylonus , English Bokmakierie ) the finch bird ( Crithagra albogularis , English White-throated Canary ) and Kapammer ( Emberiza capensis , English Cape Bunting ) and Emberiza impetuani ( English Lark-like Bunting ), both of which belong to the bunting .

According to a study by Paul van den Elzen on the herpetofauna of the Brandberg massif, there are 26 species of lizards here, some of which are very common. The Pachydactylus gaiasensis ( English Brandberg thick-toed gecko ) is endemic . Of the five occupied frogs, tadpoles are often seen in open water. The ten species of snake include the Angolapython ( Python anchietae ), the brown house snake ( Boaedon fuliginosus ), the Mopane snake ( Hemirhagerrhis nototaenia viperina ), the Karoo sand snake ( Psammophis notostictus ), Psammophis sipibilans leopardinus snake ( English: African leopardin snake ) , Pythonodipsas carinata ( English Western Keeled snake ), long considered a subspecies of the African spitting cobra ( Naja nigricolis nigricincta ) run, but now a separate species Naja nigricincta (Zebra snake or zebra spitting cobra), the puff adder ( Bitis arietans ) and the Horned Puff Adder ( Bitis caudalis ). A total of 41 forms of amphibians and reptiles are known on the Brandberg. The scorpions are particularly diverse with 20 different species in seven genera ( Brandbergia , Lisposoma , Hottentotta , Parabuthus , Uroplectes , Hadogenes and Opistophthalmus ) in four families ( Bothriuridae , Buthidae , Hemiscorpiidae , Scorpionidae ). The occurrence on the Brandberg is considered to be the richest scorpion fauna in Namibia, if not in all of southern Africa, and is one of the richest scorpion fauna in the world. The jumping spiders are also well represented , of which nineteen different species occur in the area of the Brandberg, including the Mashonarus brandbergensis , which is named after the locality .

The animal world depicted in the numerous rock paintings in the mountains cannot be found in the Brandberg massif. Even if the climate during the lifetime of the rock art artists may have been a little different than it is today, the upper part of the mountain will have remained inaccessible to the large mammals mainly represented. Remarkably, the animals that come into question as food and, like rock hyrax demonstrably also hunted, are almost not shown at all among the rock art.

The Brandberg massif recently came under the spotlight of research due to the sensational discovery of a new order of insects , the so-called gladiators , which only occur in this indigenous region. A German-Namibian student from the University of Bremen was significantly involved in the discovery and identification of species, while another German contributed to further research. The gladiators are currently (2005) still being investigated by entomologists.

Other living fossils are two representatives of the genus Alavesia from the family of the humpback dance flies (Hybotidae). Up until 2007, these animals were only known from 112–89 million year old amber inclusions from northern Spain and Burma. Sinclair and Kirk-Spriggs report in 2009 that the first living flies of this genus were detected on the Brandberg massif as early as 1998. Among the insects which are for the Brandenberg area long leg fly Schistostoma brandbergensis , the worm Lion Leptyoma monticola , to the Mythicomyiidae belonging to the genus Hesychastes and the type Psiloderoides dauresensis endemic.

economy

National Monument and World Heritage candidate

Since June 15, 1951, the Brandberg massif has been part of the national heritage of Namibia . Since 2002, the Brandberg massif has also been a candidate for World Heritage in Namibia and is entered in a tentative list of sites that are intended for nomination for inclusion in the World Heritage list.

Agriculture and tourism

Agricultural use of the Brandberg massif or parts of it has not taken place in the last hundred years and will not play a role in the foreseeable future. Today the Brandberg massif is mainly known for the rock paintings and rock engravings, which have a considerable share in the touristic importance and development of the mountain massif, which stands on the border with mass tourism. In view of the need to hire a licensed guide from the Brandberg Community Tourist Project for the hike to the White Lady , for example, the presence of the guides ensures the protection of the works of art and also contributes to the employment of the population. The grandiose nature that emerges from the weathering of the various granite varieties and above all the nimbus of Namibia's highest mountain lead to a further tourist component with opportunities for mountain hiking and rock climbing. The Königsstein, the highest point in the Brandberg massif, can also be climbed. However, this is only possible with a guide in the months with moderate temperatures (April to August / September) as part of a multi-day tour. The cheapest route starts from the seaside.

Mining

Although the “Brandberg West Mine” bears the suffix “Brandberg”, it is about 45 km from the Brandberg massif. Tin and tungsten ores were mined here from 1946 to 1980. The Brandberg massif itself contains in the aegirine-arfvedsonite-containing rocks of the "Amis Layered Complex" total rock contents of up to 1600 ppm tin and up to 1800 ppm zinc. A possible mining of the mineralization is out of the question due to the classification of the massif as a national monument.

A rock consisting mainly of pyrophyllite has been mined sporadically in the Amis Gorge on the western slopes of the Brandberg. B. also in the Hungorob Gorge. The pyrophyllite is associated with deep reddish-brown pelites of the Karoo sequence, which were subjected to a low-grade metamorphosis and an acidic metasomatosis. The pelites are in contact with the peralkaline granites of the "Amis Layered Complex". The pyrophyllite is likely to have formed metasomatically during the interaction between fluids and the bedrock at low temperatures. The altered sediment consists of fibrous pyrophyllite crystals in combination with quartz, hematite as well as accessory tourmaline and zircon. In the past, mining was only carried out very irregularly. The relatively soft material is called “Brandberg Pyrophyllite” and is used for stone carvings (ashtrays, decorative objects) that were offered in souvenir shops (in Windhoek, but also in Uis).

Although the massif a designated national monument and therefore the collection of minerals is expressly prohibited here (B. Orabes z.) Found in recent years in the southeastern canyons of the massif an illegal mining of minerals such as on feldspar seated Amethyst -Zepterkristallen, epidote , Prehnite , magnetite and zeolites instead. In 2007 topaz crystals from here with attractive liquid inclusions reached the mineral market. The topaz crystals, up to 16 cm in size, are among the largest representatives of this mineral type ever found in Namibia. Amethyst scepter crystals with a very strong purple but uneven color were found in the area of the Brandberg massif as early as the 1930s. They often show zonal stratification and an hourglass-shaped distribution of color as well as numerous inclusions, including fluid inclusions with a dragonfly.

“Brandberg” is also incorrectly used as a location for the minerals found in the Gobobosebberge (Tafelkop) or in the Messum crater such as amethyst, prehnite or zeolites.

literature

- Wolfgang Bauer: The Prospector: The Prospector. An illustrated story about the Brandberg in Namibia . Benguela Publishers, Windhoek 2008, ISBN 978-3-936858-79-2 , pp. 1-296 .

- Goodman Gwasira: Rethinking the archeology of the Dâures Mountain in a post-colonial context , In: Namibia Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft Journal, Edition 66, 2018, ISBN 978-99945-76-60-9 , pp. 113ff.

- Claire Küpper, Thomas Küpper: Namibia Nature Reserves: Travel Guide . 2nd Edition. Iwanowski's Reisebuchverlag, Dormagen 2003, ISBN 3-923975-60-0 , p. 1-572 .

- Tilman Lenssen-ore, Marie-Theres ore: Brandberg. Namibia's Bilderberg . J. Thorbecke Verlag, Ostfildern 2000, ISBN 3-7995-9030-7 , p. 1-128 .

- Peter Breunig: The Brandberg: Investigations into the settlement history of a high mountain range in Namibia (monographs on the archeology and environment of Africa, Vol. 17) . 1st edition. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-927688-23-1 , p. 1-296 .

- Peter Breunig: Archaeological Travel Guide Namibia . Africa Magna Verlag, Frankfurt 2014, ISBN 978-3-937248-39-4 , pp. 1-328 .

See also

Web links

- Official website for the Brandberg National Monument (English)

- Rock paintings on the Brandberg

- Mineral atlas

- Minerals from Brandberg, Namibia

Individual evidence

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung, article "Brandberg: Much more than the highest mountain in Namibia" from May 28, 2010 by Anonymus

- ^ A b Charles John Andersson : The Okavango-River: a narrative of travel, exploration and adventure . 1st edition. Hurst and Blackett Publishers, London 1861, pp. 1-364 .

- ↑ Charles John Andersson : The Okavango Current: Voyages of Discovery and Hunting Adventures in Southwest Africa . 1st edition. Wolfgang Gerhard, Leipzig 1863, p. 1-257 .

- ^ Georg Gürich : German Southwest Africa. Travel pictures and sketches from the years 1888 and 1889 (communications from the Geographical Society in Hamburg 10, No. 1, 1891-92) . 1st edition. Geographischer und Nautischer Verlag L. Friederichsen & Co, Hamburg 1891, p. 1-216 .

- ^ British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers - Map of Damara and Great Namaqua Land and the Adjacent Countries to and beyond Lake Ngami as explored and surveyed by Messrs Galton & Andersson

- ^ A b Albert Viereck: The traces of the old Brandberg inhabitants (= Scientific research in South West Africa . Volume 6 ). 1st edition. SWA Scientific Society, Windhoek 1968, p. 1-80 ( namibiana.de ).

- ^ Gabriël Stefanus Nienaber, Peter E. Kaper: Toponymica Hottentotica . 1st edition. Suid-Afrikaanse Naamkundesentrum, Raad vir Geesteswetenskaplike Navorsing, Pretoria 1977, ISBN 0-86965-436-5 , p. 1-502 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Peter Breunig: The Brandenberg: Studies on the settlement history of a high mountain in Namibia (= Monographs on archeology and environmental Africa . Band 17 ). 1st edition. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-927688-23-1 , p. 1-296 .

- ↑ Goodman Gwasira: Rethinking the archeology of the Dâures Mountain in a post-colonial context , In: Namibia Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft Journal, Edition 66, 2018, ISBN 978-99945-76-60-9 , pp. 113ff.

- ^ Ferdinand Lempp: Exploration work by the surveying team in Hochbrandberg 1914 . In: Journal of the SWA Scientific Society . tape 1959/60 , 1960, pp. 39-41 .

- ↑ Blogspot - Claus Burfeindt

- ↑ Claus Burfeindt: The way to the Brandberg . 1st edition. Self-published, 1970, p. 1–52 ( amazonaws.com [PDF; 8.5 MB ; accessed on June 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung Zeitung Namibia, February 1955 (incomplete source)

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung, article “100 years ago - first ascent of the Königstein in the Brandberg massif” from December 19, 2017 by Anonymus

- ↑ a b Allgemeine Zeitung, article "Successful" anniversary ascent "of the Königstein in the Brandberg massif" from January 9, 2018 by Wiebke Schmidt

- ↑ Jana Moser: Investigations into the history of cartography in Namibia: The development of mapping and surveying from the beginnings to independence in 1990: Appendix volume (unpublished dissertation) . Technical University of Dresden, Faculty of Forest, Geo and Hydro Sciences, Dresden 2007, p. F-24 ( qucosa.de [PDF; 42.2 MB ; accessed on June 20, 2018]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Peter Breunig: Temperatures and precipitation in the Hohe Brandberg: On the ecological favorable situation of a high mountain on the eastern edge of the Central Namib Desert . In: Journal Namibia Scientific Society . tape 42 , 1990, pp. 7-24 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j BJ Michael Diehl: Geology, mineralogy, geochemistry and hydrothermal alteration of the Brandberg alkaline complex, Namibia . In: Geological Survey of Namibia Memoir . tape 10 , 1990, pp. 1–55 ( gov.na [PDF; 30.0 MB ; accessed on June 19, 2018]).

- ↑ a b c Axel K. Schmitt, Rolf Emmermann, Robert B. Trumbull, Bernhard Bühn, Friedhelm Henjes-Kunst: Petrogenesis and 40 Ar 39 Ar Geochronology of the Brandberg Complex, Namibia: Evidence for a Major Mantle Contribution in Metaluminous and Peralkaline Granites . In: Journal of Petrology . tape 41 , no. 6 , 2000, pp. 1207–1239 , doi : 10.1093 / petrology / 41.8.1207 ( silverchair.com [PDF; 647 kB ; accessed on June 19, 2018]). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Klaus Hüser, Helga Besler, Wolf Dieter Blümel, Klaus Heine, Hartmut Leser, Uwe Rust: Namibia: A Landscape Science in Pictures (Edition Namibia No. 5) . 1st edition. Klaus Hess Verlag, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-933117-14-3 , p. 84-85 .

- ↑ Republic Namibia Directorate of Surveying and Mapping (Ed.): Namibia 1: 250 000 sheet 2114 Omaruru . 3. Edition. Directorate of Surveying and Mapping, Windhoek 2003.

- ^ A b c Hans Cloos , Karl F. Chudoba : Der Brandberg. Construction, formation and shape of the young plutons in South West Africa . In: New Yearbook for Mineralogy, Geology and Paleontology . Beil.-Bd. 66B, 1931, pp. 1-130 .

- ↑ Hermann Korn , Henno Martin : The intrusion mechanism of the large Karroo-Plutons in South West Africa . In: Geologische Rundschau . tape 41 , no. 1 , 1953, p. 41-58 .

- ^ A b Frank DI Hodgson: Petrography and evolution of the Brandberg intrusion, South West Africa . In: Linley A. Lister (Ed.): Symposium on granites, gneisses and related rocks, Salisbury, August / September, 1971: Special Publication of the geological Society of South Africa . tape 3 . Geological Society of South Africa, Johannisburg 1973, p. 339-343 (English).

- ^ Oleg von Knorring: A note on tin-tantalum pegmatites in the Damara Orogen and alkali rocks associated with the Brandberg Complex . In: Communications of the Geological Survey of SW Africa / Namibia . tape 2 , 1985, pp. 63-64 .

- ↑ JE Potgieter: Anorogenic alkaline ring-type complexes of the Damaraland Province, Namibia, and Their economic potential (unpublished thesis M. sc.) . Rhodes University, Faculty of Science, Geology, Grahamstown 1987, pp. 1-150 ( core.ac.uk [PDF; 18.4 MB ; accessed on June 26, 2018]).

- ↑ C. blow, Alexander Will Gallis: Short Communication: Similarities in tin mineralization associated with the Brandberg granite of SWA / Namibia and granites in northern Nigeria . In: Journal of African Earth Sciences . tape 7 , no. 1 , 1988, p. 307-310 .

- ↑ Axel K. Schmitt, Robert B. Trumbull, Peter Dulski, Rolf Emmermann: Zr-Nb-REE mineralization in peralkaline granites from the Amis Complex, Brandberg (Namibia): evidence for magmatic pre-enrichment from melt inclusions . In: Economic geology and the bulletin of the Society of Economic Geologists . tape 97 , no. 2 , 2002, p. 399-413 , doi : 10.2113 / gsecongeo.97.2.399 .

- ^ Franco Pirajno: Mineral resources of anorogenic alkaline complexes in Namibia: A review . In: Australian Journal of Earth Science . tape 41 , no. 2 , 2007, p. 157-168 , doi : 10.1080 / 08120099408728123 .

- ↑ Peter Bowden, Judith A. Kinnaird, Michael Diehl, Franco Pirajno: Anorogenic granite evolution in Namibia: A fluid contribution . In: Geological Journal . tape 25 , no. 3-4 , 1990, pp. 381-390 .

- ↑ Ronald T. Watkins, Ian McDougall, Anton P. le Roex: K – Ar ages of the Brandberg and Okenyenya igneous complexes, north-western Namibia . In: Geologische Rundschau . tape 83 , no. 2 , 1994, p. 348-356 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-662-38521-0_11 .

- ^ Matthias J. Raab, RW Brown, K. Gallagher, Klaus Weber, AJW Gleadow: Denudational and thermal history of the Early Cretaceous Brandberg and Okenyenya igneous complexes on Namibia's Atlantic passive margin . In: Tectonics . tape 24 , 2005, pp. TC3006 , doi : 10.1029 / 2004TC001688 .

- ↑ Tim Vietor, Robert B. Trumbull, Norbert R. Nowaczyk, David G. Hutchins, Rolf Emmermann: Insights on the deep roots of Mesozoic ring complexes in Namibia from aeromagnetic and gravity modeling of the Messum and Brandberg complexes . In: Journal of the German Geological Society . tape 152 , no. 2–4 , 2001, pp. 157-174 , doi : 10.1127 / zdgg / 152/2001/157 .

- ^ Karl F. Chudoba : "Brandbergite", an aplitic rock from the Brandberg (SW Africa) . In: Central Journal of Mineralogy, Geology and Paleontology Department A. . tape 1930 , 1931, pp. 389-395 .

- ↑ a b Die Zeit, article «Obsessed by this art» from June 9, 2016 by Urs Willmann

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung, article «Felsmalereien give riddles» from July 9, 2010 by Anonymus

- ^ Tilman Lenssen-Erz, Marie-Theres Erz: Brandberg. Namibia's Bilderberg . J. Thorbecke Verlag, Ostfildern 2000, ISBN 3-7995-9030-7 , p. 1-128 .

- ^ Harald Pager : The Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg . Part I: Amis Gorge. Ed .: Rudolph Kuper (= Africa Praehistorica . Volume 1 ). 1st edition. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-927688-01-0 , p. 1-502 (English).

- ^ Harald Pager : The Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg . Part II: Hungorob Gorge. Ed .: Rudolph Kuper (= Africa Praehistorica . Volume 4 ). 1st edition. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-927688-05-3 , p. 1-502 (English).

- ^ Harald Pager : The Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg . Part III: Southern Gorges. Ed .: Rudolph Kuper (= Africa Praehistorica . Volume 7 ). 1st edition. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-927688-09-6 , p. 1-543 (English).

- ^ Harald Pager : The Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg . Part IV: Umuab and Karoab Gorges. Ed .: Rudolph Kuper (= Africa Praehistorica . Volume 10 ). 1st edition. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-927688-16-9 , p. 1-423 (English).

- ^ Harald Pager : The Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg . Part V: Naib Gorge (A) and the Northwest. Ed .: Rudolph Kuper (= Africa Praehistorica . Volume 12 ). 1st edition. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-927688-18-5 , p. 1-334 (English).

- ↑ a b c Paul van den Elzen: On the herpetofauna of the Brandberg, Southwest Africa . In: Bonn zoological contributions . tape 34 , no. 1-3 , 1983, pp. 293–309 ( PDF (1.4 MB) on ZOBODAT ).

- ^ Mindat - Brandberg

- ^ JH van der Merwe: National Atlas of South West Africa . 1st edition. University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch 1983, ISBN 0-7972-0020-7 .

- ^ A b Heinrich Johann Wilhelm ("Willy") Giess: A preliminary vegetation map of South West Africa . In: Dintera . tape 4 , 1971, p. 31-114 .

- ↑ a b c d Patricia Craven, Dan Craven: The Flora of the Brandberg, Namibia . In: Ashley H. Kirk-Spriggs, Eugène Marais (Ed.): Biodiversity of the Brandberg Massif, Namibia. Cimbebasia Memoir . tape 9 . State Museum of Namibia, Windhoek 2000, p. 49-67 ( ox.ac.uk [PDF; 281 kB ; accessed on April 30, 2018]).

- ↑ Eberhard von Koenen: Medicinal and poisonous plants in South West Africa . 1st edition. Academic Publishing House, Windhoek 1977, ISBN 0-620-02887-4 .

- ^ Hermann Merxmüller , KP Butler: Nicotiana in the African Namib - a plant-geographical and phylogenetic puzzle . In: Communications from the Botanical State Collection, Munich . tape 12 , no. 15 , 1975, p. 91-104 .

- ↑ Desmond T. Cole: Lithops: Flowering Stones . 1st edition. Acorn Books, Johannesburg 1988, ISBN 0-620-09678-0 , pp. 1-254 .

- ↑ Linda C. Prinsloo, Aurélie Tournié, Philippe Colomban, Céline Paris, Stephen T. Bassett: In search of the optimum Raman / IR signatures of potential ingredients used in San / Bushman rock art paint . In: Journal of Archaeological Science . tape 40 , no. 7 , 2013, p. 2981–2990 , doi : 10.1016 / j.jas.2013.02.010 .

- ↑ Linda C. Prinsloo: Rock hyraces: a cause of San rock art deterioration? In: Journal of Raman Spectroscopy . tape 38 , no. 5 , 2007, p. 496–503 , doi : 10.1002 / jrs.1671 .

- ^ A b CJ Brown: Birds of the Brandberg and Spitzkoppe . In: Lanioturdus . tape 26 , no. 1 , 1991, p. 25–29 ( the-eis.com [PDF; 138 kB ; accessed on June 20, 2018]).

- ↑ Lorenzo Prendini, Tharina L. Bird: Scorpions of the Brandberg Massif, Namibia: Species richness inversely correlated with altitude . In: African Invertebrates . tape 49 , no. 2 , 2008, p. 77-107 , doi : 10.5733 / afin.049.0205 ( bioone.org [PDF; 2.5 MB ; accessed on June 20, 2018]).

- ↑ Wanda Wesolowska: Jumping spiders from the Brandberg massif in Namibia (Araneae: Salticidae) . In: African Entomology . tape 14 , no. 2 , 2006, p. 225-256 .

- ↑ Klaus-Dieter Klass, Oliver Zompro, Niels-Peder Kristensen, Joachim Adis: Mantophasmatodea: Mantophasmatodea: A New Insect Order with Extant Members in the Afrotropics . In: Science . tape 296 , 2002, pp. 1456-1459 .

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung, article "New Order" from March 19, 2002 by Anonymus

- ↑ Sensational insect discovery: Bremen biologist discovers living "fossils" in Namibia. ( Memento of June 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Press release No. 219 / October 10, 2002 of the University of Bremen.

- ↑ Bradley J. Sinclair, Ashley H. Kirk-Spriggs: Brandberg Massif (Namibia) serves up another living fossil! In: Fly Times . tape 42 , no. 2 , 2009, p. 2–3 ( nadsdiptera.org [PDF; 3.6 MB ; accessed on June 20, 2018]).

- ^ Ashley H. Kirk-Spriggs & Brian R. Stuckenberg, Afrotropical Diptera - Rich Savannas, Poor Rainforests . In: Thomas Pape, Daniel John Bickel, Rudolf Meier (Eds.): Diptera Diversity: Status, Challenges and Tools . Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden & Boston 2009, ISBN 978-90-04-14897-0 , pp. 155–196 , doi : 10.1163 / ej.9789004148970.I-459 (English).

- ↑ a b c Brandberg National Monument: National Monuments - Brandberg (English)

- ^ Andreas Vogt: National Monuments in Namibia . 1st edition. Gamsberg Macmillan, Windhoek 2004, ISBN 99916-0-593-2 , pp. 1-252 .

- ↑ Majka Burhardt: Namibia: Brandberg, Southern Crossing . In: American Alpine Journal - The American Alpine Club . tape 2010 , 2010, p. 213–215 ( amazonaws.com [PDF; 6.7 MB ; accessed on June 26, 2018]).

- ↑ Activities and sights in the Brandberg massif

- ^ Franco Pirajno, VFW Petzel, Roger E. Jacob: Geology and alteration-mineralization of the Brandberg West Sn-W deposit, Damara orogen, South West Africa / Namibia . In: South African Journal of Geology . tape 90 , no. 3 , 1987, pp. 256–269 ( the-eis.com [PDF; 798 kB ; accessed on June 20, 2018]).

- ^ Gabi IC Schneider: Talc and Pyrophyllite . In: Republic of Namibia Ministry of Mines and Energy Geological Survey (Ed.): The Mineral Resources of Namibia . 1st edition. Republic of Namibia Ministry of Mines and Energy Geological Survey, Windhoek 1992, ISBN 0-86976-258-3 , p. 6.25-1–6.25-2 (English).

- ^ A b Gabi IC Schneider, Steffen Jahn: The Brandberg and the mineral finds in its area . In: Steffen Jahn, Olaf Medenbach, Gerhard Niedermayr, Gabi IC Schneider (Hrsg.): Namibia: Magic world of precious stones and crystals . 2nd Edition. Bode-Verlag, Haltern am See 2006, ISBN 3-925094-86-5 , p. 37-53 .

- ↑ Ludi van Bezing, Rainer Bode, Steffen Jahn: Namibia: Minerals and sites . 1st edition. Bode-Verlag, Salzhemmendorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-925094-88-0 , p. 268-296, 686 .

- ↑ Ludi van Bezing, Rainer Bode, Steffen Jahn: Namibia: Minerals and Localities I . 1st edition. Bode-Verlag GmbH, Salzhemmendorf 2014, ISBN 978-3-942588-13-3 , p. 40-49 .

- ↑ G. Menzer: About amethysts from Brandberg in German South West Africa . In: Central Journal of Mineralogy, geology, paleontology Abbot A. . tape 1936 , 1936, pp. 289-290 .