Winterthur Cantonal Hospital

| Winterthur Cantonal Hospital | ||

|---|---|---|

| Aerial photo of the KSW from 2007 | ||

| Sponsorship | Public law institution | |

| place | Winterthur | |

| Canton | Zurich | |

| Country | Switzerland | |

| Coordinates | 697 210 / 262604 | |

| management | * Rolf Zehnder, Hospital Director * Franz Studer, President of the Hospital Council |

|

| Care level | Central hospital | |

| beds | 500 | |

| Employee | 3,294 (2019 annual report) | |

| including doctors | 619 (2019 annual report; CA / LA, OA, AA) | |

| Annual budget | 552.8 million CHF (2019 annual report) | |

| founding | 1876 (as "residents' hospital") or 1886 (taken over by the canton and renamed) | |

| Website | www.ksw.ch | |

| Location of the hospital | ||

|

|

||

The Kantonsspital Winterthur ( KSW ) provides medical care for the Winterthur region in the canton of Zurich . The public institution is the tenth largest hospital in Switzerland with around 500 beds and treats around 200,000 inpatients and outpatients annually.

The 90-bed residents' hospital, which was built under the direction of the Winterthur architect Emil Kaspar Studer and the Winterthur city architect Joseph Bösch and opened in November 1876, was taken over by the Canton of Zurich ten years later and renamed the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital . Over the years, a campus with numerous different buildings has grown in the center of the city of Winterthur, which housed the most diverse disciplines. In 1978 the KSW received the status of a central hospital with supraregional tasks.

The hospital has six delivery rooms and 15 operating theaters (as of 2017). 3294 employees (2465 full-time equivalents ) ensured that 28,024 inpatient withdrawals took place in 2019 . In the same year 125,605,410 tax points were earned with outpatient services and 1,781 children, including twins and triplets, were born. With a case mix index (CMI) of 1.033, the patients spent an average of 4.9 days in the cantonal hospital.

Location and description

The Kantonsspital Winterthur is located in the heart of the city, north of the Winterthur train station in the Lind district of Stadtkreis 1 (city) . Most of the buildings are located at the foot of the Lindberg on the 5.6 hectare site between - clockwise from the west - Brunngasse, Brauerstrasse, Haldenstrasse and Lindstrasse.

Treatments for patients take place in the high-rise (building H), bed building (building D), treatment (building E), polyclinic (building F) and connecting wing (building C), east wing (building K), pavilion (building Q) and the newly built radio-oncology (house R) and in the therapy bath (house T). The company building with workshops, the fire department depot, various laboratory facilities, the laundry and various administrative buildings are also located on campus. The buildings differ significantly in their architectural style due to the different times they were built.

Some rooms are located outside the main site: Certain administrative areas are housed in rented buildings. In addition, the parking garage for visitors is located across from Lindstrasse, the daycare center across from Haldenstrasse (Building Y) and staff houses (Building U) on Albanistrasse and Gottfried-Keller-Strasse. The construction site for the replacement “didymos” building is currently located south of the high-rise.

Mission and organization

According to the cantonal law on the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSWG) of September 19, 2005, the hospital is an institution under cantonal public law with its own legal personality and headquarters in Winterthur. The purpose of this is to provide supraregional medical care, support for research and teaching at universities, and support for basic, advanced and advanced training in health care professions. The Zurich Cantonal Council exercises overall supervision , while the Government Council exercises general supervision and defines the service mandates by means of a hospital list .

Within the cantonal hospital, the hospital council is the highest management body, which is elected by the government council for four years. He is responsible for the supervision of the hospital management and for the fulfillment of the state service mandates as well as for the strategic orientation of the hospital; He is currently chaired by Franz Studer. The hospital management with twelve members and the hospital director is responsible for the operational implementation of the strategy and the commercial result of the hospital. The hospital management includes the heads of the departments, a delegation from the institutes and the general services; It is currently managed by the hospital director Rolf Zehnder.

The KSW is structured as a matrix organization and is divided into departments, clinics, institutes, interdisciplinary departments and centers as well as support areas:

Departments, institutes and centers

- Department of Surgery : Clinic for Vascular Surgery, Clinic for Hand and Plastic Surgery, Clinic for Maxillofacial Surgery, Clinic for Neurosurgery, Clinic for Orthopedics and Traumatology, Clinic for Urology, Clinic for Visceral and Thoracic Surgery, Center for Child Surgery

- Department of Medicine : Angiology, Endocrinology / Diabetology, Gastroenterology, Infectiology, Nephrology / Dialysis, Rheumatology, Allergology / Dermatology, Cardiology, Medical Oncology, Medical Polyclinic, Neurology, Pneumology

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology : Clinic for Obstetrics, Clinic for Gynecology

- Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine : Clinic for Neonatology, Clinic for Pediatric / Adolescent Medicine and Psychosomatics, Social Pediatric Center SPZ, special consultation hours

- Eye clinic

- Institutes: Institute for Anaesthesiology , Institute for Laboratory Medicine , Institute for Pathology , Institute for Therapy and Rehabilitation , Institute for Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Institute for Radio-Oncology

- Interdisciplinary departments: emergency center, operating theater, center for intensive medicine

- Centers: tumor center, vascular center, perinatal center, simulation center

- Support areas: HR , Services & Supply, Organizational Development / ICT / Technology / Construction, Finance

research

The Kantonsspital Winterthur is legally obliged to support research and teaching as well as to promote basic, advanced and advanced training in health care professions. At the KSW, a research commission made up of eleven members from different clinics and professional groups approves standards and regulations for conducting studies in-house and advises the management on questions of research strategy. The Central Study Coordinates, which is subordinate to the Research Commission, functions as a central reporting and coordination point for studies at the KSW. Ongoing studies at the hospital are made available to the public.

In 2019, 39 new research projects started at the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital - in the departments of medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology as well as the institutes for radiology and nuclear medicine, therapies and rehabilitation, anesthesiology and radio-oncology - an increase of over 40% compared to the last one Year corresponds. The tumor and breast centers, which work in cancer medicine , especially in medical oncology , participate in national and international projects and are members of the Swiss Working Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), deserve special mention. In addition, a scientific study on preclinical resuscitation launched in 2015 ended in 2019 ; of 88 people examined, 35% could be brought to hospital alive, which is well above the European average of 25%.

Directors

The hospital was initially headed by a so-called "host". In the 1930s this person was called the "administrator" who ran the hospital. At the same time, the chairman of the chief physicians' conference - which the government council usually elected for four years - was the external representative and was a member of various commissions, including the small building commission. The hospital director has been at the top of the hierarchy since 1995. Rolf Zehnder currently (as of 2020) exercises this function.

Home owners

- 1871–1879 Hermann Koller-Sulzer

- 1879–1887 Heinrich Ziegler-Schäppi

- 1910-1933 A. Lyem

Administrator or administrative director, from 1995 hospital director

- 1933–1956 Eduard Albrecht

- 1956–1973 Max Roth

- 1973–1981 Hermann Schenkel

- 1981–2008 Jacques F. Steiner

- since 2008 Rolf Zehnder

Medical hospital directors, from 1971 chairperson of the chief physicians' conference:

- 1887–1899 Karl Walder

- 1899–1922 Robert Stierlin

- 1922–1926 Otto Roth

- 1926–1932 Emil Looser

- 1932–1935 Hans Conrad Brunner

- 1935–1936 Emil Looser

- 1936–1939 Otto Roth

- 1939–1948 Otto Schürch

- 1948–1960 Hans Conrad Brunner

- 1960–1963 Adolf Max Fehr

- 1963–1967 Ferdinand Wuhrmann

- 1967–1977 Erich Glatthaar

- 1978–1982 Walter Bessler

- 1983–1987 Bruno Egloff

- 1988–1996 Adolf Hany

story

First predecessor institutions: 13th to 19th centuries

In the Middle Ages it was mostly the monasteries and religious communities who cared for the poor and the sick. In the 13th and 14th centuries, Winterthur had 1,500 to 2,000 citizens, plus mercenaries, pilgrims and merchants ensured a brisk through traffic between Zurich , the Rhine and Lake Constance . At that time there was no rich monastery in Winterthur that could have taken on the task, and due to its size, the need for health care increased.

The “Sondersiechenhaus zu St. Georgen”, founded by Duke Rudolf of Austria and the City of Winterthur, is mentioned as one of the first health facilities in Winterthur . The document that existed between the city and the duke is dated May 24, 1287. Only lepers who suffered from leprosy (also known as "special sickness") were accommodated in the facility . The house stood outside the city wall and by the stream that ran away from the city in order to avoid possible contamination of the city's water supply. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the leprosy disease slowly declined, which is why the special hospital was turned into a beneficiary (poor house, old people's home) for people unable to work. On February 25, 1813, the city council decided to cease operations because the beneficiary house on Neumarkt could be moved into. The dilapidated building was demolished in 1828 - with the exception of the chapel, which had to give way in 1882 for the construction of the northeast railway.

As early as 1306, a poor and hospital institution at today's Neumarkt in the old town of Winterthur is mentioned as a foundation of the citizenship at the time. This was called Heiliggeist-Spital, due to a donation of an altar to the Holy Spirit by Queen Agnes of Hungary to the collegiate chapel in Königsfelden . It was later referred to as the “lower hospital” and was considered the opposite of the “upper hospital”, where wealthier citizens were treated. The upper hospital was sold in 1528 and moved to the house next to the lower hospital. For more than 200 years, the two facilities served for old-age and social welfare, for sick treatment, as an orphanage and accommodation for undemanded travelers, until they no longer met the requirements, gradually demolished from 1788 to 1814 and rebuilt at the same place - with various extensions were. After the new opening, the hospital was called "Bürgerliche Pfrund-, Armen- und Krankenanstalt" and in the 1860s 200 to 300 patients were treated.

Residential Hospital: 1876–1885

The flourishing industry, including the Sulzer brothers, Giesserei in Winterthur and J. J. Rieter & Cie. , as well as the increasing traffic caused the city of Winterthur a large population growth in the middle of the 19th century with many new arrivals. The previous hospital on Neumarkt was no longer able to cope with the number of patients, which is why there were demands for a residents' hospital that should be open to all residents of the city.

At the citizens' meeting on January 18, 1869, those present therefore made the following motions:

- Separation of the hospital from the civil poor and subordinate the political community as a special foundation.

- In addition to the contribution to be made from the poor, the new foundation should receive an appropriate contribution from the political community.

- This new organization is to apply to the previous hospital for the next eight to ten years, until a new building is built.

Despite the desire for a new hospital, the financial means were lacking, and the Zurich cantonal government even rejected a request to contribute to the construction costs. Private collections, supported by Mr. Imhoof-Hotze with 100,000, Brothers Sulzer with 25,000 and Rieter with 10,000 francs , resulted in a total financial contribution of 250,000 francs. The political community and the civil parish spoke an additional 341,730 francs, which is why at the community meeting on December 21, 1873 the decision was made that a new institution should be built at the southwestern foot of the Lindberg.

Construction work began in May 1874 under the direction of the architect Emil Kaspar Studer (1844–1927) and the city master builder Joseph Bösch (1839–1922). On November 15, 1876, the “residents' hospital” with 90 beds was opened, and from then on, the sick and poor were separated. Another building followed in 1877, a morgue.

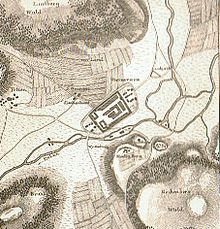

Location of the hospital at the foot of the Lindberg, Siegfried Atlas (1881)

Takeover by the Canton of Zurich

Just a few years after the opening of the new hospital, voices were raised in favor of a takeover by the Canton of Zurich . On June 21, 1880, the communities in the districts of Andelfingen , Bülach and Pfäffikon submitted a petition to the Zurich Cantonal Council. The «Cantonal non-profit society for the decentralization of the hospital system» submitted another one year later. Due to the national railway debacle in 1878, the city of Winterthur slipped into a serious debt crisis and the first negotiations on the sale of the hospital to the canton followed from December 1880 to May 1881 - at a price of 450,000 francs. However, the negotiations were postponed due to the unclear financial situation of the city of Winterthur and only resumed in December 1884. On December 7, 1884, a meeting took place in the casino in Winterthur , where a new request for an early drafting of a bill was submitted to the Cantonal Council.

Although the dean of the medical faculty as early as December 1, 1880 and an expert report from July 15, 1885 by Professors Hermann Eichhorst , Rudolf Ulrich Krönlein , Johann Friedrich Horner and Oskar Wyss demanded that the Winterthur residents' hospital become a "branch" of the Zurich Cantonal Hospital Winterthur strongly opposed it. The demotion to a supply or catering establishment was intended as a consideration that teaching and teaching should remain in Zurich. After much deliberation, the government council sided with Winterthur, but reduced the purchase price to CHF 400,000.

On August 5, 1885, a contract for the takeover by the canton was drawn up. Among other things, it regulated that the residents' hospital should continue to be operated as a sanatorium. Likewise, CHF 200,000 of the purchase price was to be donated through a donation from Winterthurer J. Schoch. The other 200,000 francs were deducted from a loan to the city of Winterthur of one million francs in installments of 50,000 francs over the course of three years. On December 6, 1885, a cantonal referendum vote took place under the name “Takeover of the Winterthur residents' hospital by the canton”. With a participation of 59,378 voters (80.00% participation), 45,027 voted yes (83.38%) and 8,975 (16.62%) voted no. In the takeover regulations it was now also stipulated that “incurable patients from Zurich [cannot] be directed to the canton hospital”. On January 1, 1886, it was taken over by the canton and renamed the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital.

Continuous expansion of the building

| 1880 | 1881 | 1882 | 1883 | 1884 | 1885 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 458 | 701 | 1,128 | 1,325 | 1,738 | 2,228 |

| Number of audiences | 970 | 1,539 | 2,773 | 3,415 | 4,151 | 5'355 |

After the takeover by the canton, there was an increasing shortage of space, especially when the Swiss military were deployed in the area. In 1906, for example, the chief medical officer was even asked to “suspend further [troop] additions”.

In 1887 a wash house was built , which was expanded in 1905 by a modern disinfection device from the Sulzer brothers . In 1892 , the canton bought the Haldengutwiese immediately west of the hospital building for 140,000 francs as the first land expansion to cope with the increasing numbers of patients and their treatment . A single-storey segregation house with 46 beds was built on it from 1893 and moved into in 1895. Another one-story diphtheria building for around 30 patients was built next door, which went into operation in August 1897. The costs for the two buildings approved by the Cantonal Council amounted to around 293,000 francs.

The first flush toilets were set up in 1899. In 1900 an " X-ray cabinet " was set up in the basement of the segregation house for 4,300 francs. The Haldengut brewery provided the power supply free of charge - in return, the employees of the brewery in the hospital received preferential treatment - since the hospital was only connected to the city of Winterthur's electricity network in 1904. This enabled lighting in the main building and the operating room . In 1903 the kitchen was expanded and in 1907/1908 the heating system, the boiler house and the high chimney were renewed .

In 1909 a hydrotherapeutic institute opened , which carried out hot air and massage treatments as well as baths, especially a permanent bath. A new building was built to the southeast of the main building. After 14 months of construction, a polyclinic was opened on August 15, 1911 . In the three-story building there were, among other things, examination rooms, an operating room for outpatients and a pharmacist's room on the ground floor, while the other two floors housed three doctors and seven nurses as well as female economic staff .

The segregation house built in 1893 received two additional floors in 1914. After a year of construction, a new medical department was opened in the building in October 1915. Thanks to the expansion, the number of beds has increased: now 60 beds on the ground floor for infectious diseases , 65 beds on the first floor for people with scarlet fever and diphtheria and 20 beds and 12 staff rooms in the attic. The diphtheria building, which went into operation in 1897, was then rebuilt and made available to the newly introduced obstetrical department. This opened on November 1, 1916 and housed 32 beds on the ground floor, 38 women's and 25 baby beds on the first and second floors, a delivery room and an operating room as well as an eclampsia room , a laboratory and some staff rooms. In the same year the first child was born in the cantonal hospital. Around 1903 a head nurse was responsible for the procurement of medicines; she usually got them from the city's pharmacies. In 1926, after the pharmacy was enlarged, the government council appointed a pharmacist - Dr. Hans Märki - on. The hospital pharmacy was incorporated into the Canton Pharmacy Zurich (KAZ) on January 1, 1937 as a result of austerity measures .

Tripartite division of the hospital

On January 1, 1917, there was an organizational division into three independent departments with their own management: a surgical, medical and obstetric department. At that time, 49 nurses - 31 from the Zurich Red Cross , 13 from the Zurich nursing school, 2 midwives and 3 non-qualified people - were working in the hospital.

As usual up to now, the room capacity lagged behind the population growth and consequently the patient flows. Compared to the relief of the Zurich Cantonal Hospital , in which a large number of state community and district asylums were created in the city of Zurich and in the districts bordering the city, this did not happen in the city of Winterthur and the surrounding districts (Andelfingen and Pfäffikon). Waiting lists have already been used, especially in the obstetrics department. In 1918, for example, the United Health Insurance Fund - with the support of the Winterthur City Council (executive) - submitted a petition to the government council calling for the hospital to be enlarged, albeit unsuccessfully. After the reorganization in three departments, the growth was also noticeable in the medical and surgical modernization. In 1918, for example, an X-ray nurse was hired for the first time as a result of the expansion of X-ray diagnostics and an assistant doctor , and the first ambulance to replace the cab was put into operation. In 1924 there was a blood transfusion in the surgical department for the first time . From 1918 to 1925 there were only small expansions: In 1918 a double house was purchased near the hospital for the nurses and the domestic staff, in 1919/1920 a section house was built and the laundry room was expanded, and in 1921 a house for employees was built.

Since the management and administration as well as the health insurance association of Winterthur and the surrounding area and the city council, which also raised fire police concerns, repeatedly pointed out the situation, the government devoted itself to the subject from 1920. At the beginning he discussed the construction of a new segregation house, but then agreed on the proposal of the building management: an increase in the main building. The loan of 955,000 francs came on April 2, 1922 as a mandatory referendum before the people of Zurich and, with a turnout of 80.92% with 78,041 (75.40%) yes, was 25,457 (24.60%) %) No votes clearly accepted. The increase in the main building could be taken over in autumn 1925 and 53 patient beds and 54 beds for employees were available. A total of 422 normal beds were now available in the entire hospital.

Because the surgery and also the departments of medicine and obstetrics were located in the main building, the organization suffered and emergency beds soon had to be built again. As early as March 1928, the Zurich government was made aware of the space available in the obstetric department. In particular, there was no aseptic operating room or a larger delivery room and maternal women ; Gynecological patients and pregnant women were in the same room. In addition, the number of births almost doubled in just six years, from 455 in 1927 to 690 in 1933. Around 400 gynecological procedures had to be performed every year. Therefore, on May 26, 1932, the Zurich government council decided to develop a project to expand the gynecological clinic. On May 5, 1935, the people of Zurich approved a new construction of an isolated structure with a connecting wing to the old building for 867,000 francs with 84.18 percent yes-votes. It was inaugurated in 1937 and accommodated 93 adult and 43 infant beds.

In particular, the mobilization of the war in 1939 caused further capacity shortages at the cantonal hospital. The conference room in the central building was forced to be converted into a sickroom and the army built two barracks in front of the main building . The military drafted all surgeons; our own air raid protection personnel fitted all windows with splinter protection devices and filled 2,000 sandbags . In addition, blackout measures and an increase in food supplies were carried out for 19,000 francs. In the same year, the hospital organized a blood donation service for the first time with the Swiss Red Cross . In 1944, an outstation with 25 to 30 beds was opened for the surgical department. To relieve the three departments organizationally, the position of an external was in January 1945 otorhinolaryngological wizard created, among other reflections of the air and esophagus performed. In the same year, a psychiatric outpatient clinic was set up at the hospital.

1947–1970: Expansion into a central hospital

First construction stage

Even the expansions over the past 20 years did not provide a sustainable solution to the space problems. In the spring of 1942, an inventory found that there were 395 normal beds in the medical department and 138 emergency beds. Therefore, on the initiative of the then head surgeon Otto Schürch, the creation of a space program began as early as 1940/1941 and a competition was opened for a new building. The plans submitted by the Winterthur architect Edwin Bosshardt were convincing and were presented to the Zurich population on November 30, 1947, who approved the loan of 40.8 million francs with 65.65 percent of the votes.

Since the new buildings were to be built in places where buildings already existed, the construction of one building after the other and subsequent relocations to enable demolitions were inevitable. The start was made in September 1948 with a new nurses 'house on Brunngasse, which opened on October 10, 1950 and made space by moving the nurses' rooms from the attic of the main building. In 1952, a technical building for the laundry, workshops, heating including a tall fireplace , garage and kitchen was started and completed between 1954 and 1956. In order to better meet the shortage of nursing staff that had prevailed for many decades, a nursing school was founded in September 1948. In 1952 this was moved from the military barracks in front of the main building to a newly acquired house on Gottfried-Keller-Strasse and in January 1953 it was officially recognized. The medical department in the segregation house could now be accommodated on the one hand in the barracks and on the other in the vacated attic of the main building, with which the segregation house could be demolished. On November 7, 1954, the foundation stone of the nine-story ward block was laid on the site of the demolished segregation house. In the same year the "diphtheria house" was torn down so that a five-story treatment wing could be built. On June 28, 1958, the new ward block and the treatment wing were inaugurated in the presence of the Zurich government and other celebrities.

In 1958 the hospital had the following special units and services, now known as clinics: medical clinic, surgical clinic, gynecological clinic, physical therapy, x-ray department and radiation therapy, pathological institute, psychiatric polyclinic, nursing school, welfare service, administration with economics and technical service. In radiation therapy, treatment was carried out in five groups: gymnastics , massage , electro-thermal therapy , packs and baths; especially the walking bath was an asset. The radiotherapy had a new tomograph , an aorto - arteriography device and a cobalt-60 rotary device. The Pathological Institute also carried out examinations for the six Zurich hospitals Bauma , Bülach , Pfäffikon , Rorbas , Rüti and Wetzikon as well as the Thurgau hospitals in Frauenfeld and Münsterlingen .

Second construction stage

Although a conversion of the main building was only planned for the second construction phase, doubts arose as to whether this conversion would make sense during the completion work for the new ward block and the treatment wing. Various examinations showed that the basement masonry and the foundation were in very poor condition. In a few spot checks, the condition of the wooden beam ceilings above the basement, the ground floor and the first floor was found to be satisfactory; Nevertheless, the experts were of the opinion that the installation of massive ceiling structures was necessary. On the two main floors, the floor and wall coverings, the shutters, the electrical and sanitary facilities, the heating installations and most of the carpentry work had to be renewed. However, the second floor, which was later added, and the attic were in better condition. The further investigations showed that the amount budgeted in the cost estimate for the renovation of the old main building would not be sufficient and that even with greater effort, a renovation would not be worthwhile compared to a new building. Because of this, the government council decided to drop the renovation and to initiate the planning of a new building.

The project, again by the architect Edwin Bosshardt, provided for a new building for the women's and children's clinic, a staff house, the conversion and expansion of the remaining part of the old women's clinic, an underground garage and adjustments to the central technical facilities: for the women's and children's clinic He planned a simple, tower-like structure with a base area of 31 × 33 meters and a height of 50 meters, which was divided into three basement floors, the ground floor and twelve full floors as well as a recessed two-story roof structure. The building was accessed to the west via a sheltered vestibule that continued to the main entrance of the existing hospital building.

300 meters from the center of the hospital, a staff house was planned on Rychenberg- / Albanistrasse, which was divided into a U-shaped wing on the valley side and a wing adjoining it on the mountain side. It enclosed a 20 meter wide and 57 meter long inner courtyard, where the entrance to the school and to the residential floors of the upper wing is also located. The main entrance to the building is located in the lower wing on the Albanistrasse side, roughly in the middle of the wing in question. The nursing school, founded in 1948, was moved from Gottfried-Keller-Strasse to this new building - with a stopover in 1964 in the “Sulzer-Forrer-Villa”, which was then available to the psychiatric outpatient clinic as a treatment station. The regulations were also adapted in 1967 so that women were allowed to study at the school from now on; In 1970 the first sisters graduated. A comprehensive renovation and partial expansion of the remaining part of the women's clinic was planned for the polyclinic wing. For the laboratories, a small separate building was planned nearby, which was connected to the polyclinic wing via a basement. An additional full floor served the additional space requirements of the canton pharmacy and various special departments. The underground garage was supposed to be between the women's and children's clinic and Brauerstrasse. An approximately 27 × 100 meter large open parking garage with space for 66 cars - especially for doctors and employees in tenancy - was planned. The ceiling of the garage was passable and served as a parking lot. As adjustments to the technical equipment, the installation of oil firing equipment , the enlargement of the tank system, the addition of the main electrical distribution systems, the expansion of the emergency power system and the expansion of the laundry were planned.

The execution should take place in two stages: the first with a construction time of three to four years, the new construction of the women's and children's clinic, the staff house and the underground garage as well as the adjustments to the central technical facilities. The latter with a construction period of two years for the conversion of the gynecological clinic to the polyclinic wing. The estimate calculated on costs of 37.4 million francs; 28.6 million for the systems on the hospital area and 8.8 million for the staff house. Since 7.4 million francs were still available from the loan approved in 1947 and the city of Winterthur contributed two million for the construction of the additional bed level for the women's clinic, the people of Zurich only had to be presented with a loan for 28 million francs. On June 25, 1961, it approved the loan with a voting share of 50.44 percent with a yes share of 90.71 percent.

The old main building, described as a "jewel in the wreath of the city's facilities", was demolished in autumn 1961. In the spring of 1962, the new construction of the high-rise and staff building began. In 1963, the authorities found that the canton of Zurich could no longer cope with the rush for operations on the eyes; in Zurich they were already working with waiting lists. On December 23, 1963, the business audit commission of the Cantonal Council submitted a postulate to the government council asking for an audit to relieve the eye clinic. After the inspection, the decision was made that the storage area on the fifth floor of the high-rise building should be replaced by an eye clinic and that the storage rooms should be set up next to the underground car park. The population of Zurich approved the additional credit of 1.7 million francs on July 5, 1964 with a very high percentage of 94.17 percent. On January 24, 1968, the staff house on Albanistrasse was handed over to operations, and on July 2, 1968, the KSW high-rise (at that time the second tallest building in the city). Therefore, a children's clinic was opened in July 1968 and an eye clinic in February 1969 . In the same year as the opening of the eye clinic, a medical intensive care unit with eight to ten beds was introduced in the medical clinic without any major structural changes .

Third construction stage

Now the reconstruction of the polyclinic was about to be done. However, since various requirements had changed since the vote in 1961, such as the space requirements of the medical-chemical institute, the radiation department and the cantonal pharmacy, a new building was considered. In the previous building, which had been built in the crisis years 1935 to 1937 with the application of austerity measures, there were only low cavities instead of normal basement rooms and the technical installations were outdated and in poor condition. At the same time, there were also discussions about the usefulness of the planned underground garage, as valuable space would be lost for any further expansions of the cantonal hospital, as would the roof at the driveway and waiting area.

Due to the changed needs and the structural difficulties, the population was presented with a cost-neutral loan for 9.2 million francs, which was approved on March 23, 1969 with 84.6 percent of the votes. The then modern construction in an iron skeleton as well as with concrete ceilings and facade cladding allowed a quick completion of the shell; the interior work was completed at the end of 1972. On March 26, 1973, the new polyclinic wing for the pathological institute, a surgical clinic, a medical polyclinic, nuclear medicine and anesthesiology as well as a helicopter landing pad on the roof were opened. The farm building above the laundry was extended after the completion of the large buildings for the hospital pharmacy, which was previously in the building at Lindstrasse 18a, and was ready to move into in November 1975. It was possible to keep to the cost estimate for the three construction stages adjusted for inflation .

During the three construction phases, the canton hospital also implemented a number of organizational measures: in 1952 it hired a welfare worker and in 1960 a full-time pastor . In 1963, the central medical and chemical laboratory was separated from the cantonal pharmacy and a nuclear medical laboratory was set up in the X-ray department. Since from 1965 intubation anesthesia became more important than local anesthesia , the surrounding regional hospitals also wanted to participate in the more modern technology. That is why the canton hospital founded a regional anesthesia department together with the hospitals Bauma, Wald , Rüti, Uster , Wetzikon, Pfäffikon ZH, Bülach, Dielsdorf and the private clinic Lindberg - a novelty in Switzerland. In addition, various medical disciplines were added in Winterthur over the years: laparoscopy 1958, gastroscopy 1967, colonoscopy 1974. To relieve the predominantly female staff, the hospital introduced a day care center for employees for the first time in 1971 .

1970–1990: Consolidation

The three construction phases ensured immense personnel and organizational growth: from five to twelve independent specialist disciplines, from 39 to 121 doctors, from 519 to 762 beds and from 9,275 to 14,978 patient admissions. There have also been constant improvements in medicine: for example, in 1971 a department for functional occupational therapy started operations. In addition, around 1972/73 under the direction of Dr. Adolf Hany set up a heart catheter laboratory and bought a blood gas measuring device and a new laparoscope . In the same year the first provisional and 1977 the first definitive pacemaker was used in Winterthur. In 1973 the women's clinic received the first ultrasound machine .

In the hospital planning in 1978, the KSW received the status of a central hospital with supraregional tasks. Nevertheless, the company lagged behind the increasing number of patients due to various challenges: Because the hospital was not built in one go, but in stages, the spatial conditions have become too tight. Among other things, there was no above-ground connection between the hospital buildings that were occupied in 1958 and the high-rise; the surgical department and the intensive care unit no longer met the technical, hygienic and organizational requirements. The architecture firm Steiner and Steffen from Winterthur therefore presented a plan for a 39 meter long and 28 meter wide intermediate building with two underground and six above-ground floors as a connecting wing between the treatment wing and the high-rise. On September 26, 1982, the people of Zurich approved the loan of 32.3 million francs presented with 79.82 percent.

The steady growth led to the opening of new departments and in particular the introduction of new medical methods: 1978 connection to the Zentralwäscherei Zurich (ZWZ), 1981 dialysis , 1982 first bronchoscopy and 1988 opening of the angiology department , where in 1989 an angiography system with digital subtraction technology for minimally invasive therapy was purchased. In 1982 the newly created underground radiotherapy went into operation, and in 1984 the first computer tomograph was purchased . The connecting wing, which now contained an entrance hall, a kiosk , a cafeteria, a bank, the patient admission, administration, office and treatment rooms as well as a dialysis and intensive care unit, operating rooms and central sterilization , was handed over to operations in 1987.

In the "Overall Planning KSW 1988" 13 construction projects with total costs for around 147 million francs were planned, but various factors - including the introduction of the new Health Insurance Act and the general recession - led to delays or non-implementation. Individual measures, however, could be carried out, such as the renovation of the staff house on Brunngasse (whereupon administrative companies moved into the building) or in November 1993 the construction of the kitchen and east wing.

Since 1990: strong growth

In the years that followed, an increasing number of clinics and institutes emerged, such as the Clinic for Orthopedic Surgery in 1988 and the Urological Clinic in 1990. In 1991 these were divided into four departments - surgery, medicine, gynecology and pediatric and adolescent medicine. The supraregional anesthesia service founded in the 1960s was gradually made independent in the individual hospitals over the years and completely dissolved in 1991. In 1993 the KSW introduced coronary angiography and in 1994 neurology .

In 1995 the two-story east wing, which was to be located to the east of the high-rise building, and the extension of the kitchen began operations. In the same year, a magnetic resonance tomography machine was installed in the basement of the connecting wing for the first time . Therefore, in 1996 a radiological diagnostic center for computed tomography and magnetic resonance tomography was opened. At the end of 1997 the KSW was able to open a temporary ward building with 80 beds, so that the three-year renovation of the western half of the ward building could begin. In 2002 the renovation of the ward block on the east side was completed and in 2006 the renovated and expanded treatment wing was opened. On the one hand an auditorium and on the other hand a new interdisciplinary intensive care ward could be opened. In the same year, the nursing school was integrated into the Education Department of the Canton of Zurich and renamed the Nursing School at the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital.

The Radiation Oncology was separated in 2004 from the Radiology and the same year a second was linear accelerators in operation. In 2005, the Cantonal Hospital founded the Tumor Center in Winterthur. With the introduction of PACS in 2005, imaging for X-ray images was digitized and a central sterile goods supply was inaugurated . In September of the same year, the Zurich Cantonal Council wanted to pass the law on the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital, which provided for the hospital to be converted into an independent public-law institution . The law, which had become necessary due to the revision of the Health Insurance Act , had to be submitted to the people on May 21, 2006 because of the referendum that had been achieved and was adopted with 63.54 percent yes-votes. Based on this result, the KSW has been an independent public-law institution since January 1st, 2007 .

In the Urology Clinic, patients with prostate cancer have been treated using the Da Vinci robot-assisted operating system since July 2009 ; In 2016, the first small intestine replacement bladder was created in a robot-assisted operation in Switzerland. In the early summer of 2011, the hospital's employees founded the sponsoring association “Spitalpart Partnerschaft Phonsavan (Laos) –KSW” to support a hospital in the Phonsavan region . In the same year, on January 1, the hospital took over the acute geriatric assessment station from the Integrated Psychiatry Winterthur-Zürcher Unterland (IPW).

In 2012, the Uster and Wetzikon hospitals , the private tumor and breast center ZeTuP in Rapperswil, and the KSW founded the Center for Radiotherapy Zurich-East- Linth (ZRR) in Rüti , which went into operation in 2014. In 2013 the KSW opened an interdisciplinary perinatal center of the clinics for obstetrics and neonatology and in the same year a stroke unit for stroke patients ; the latter was certified as one of eight stroke centers in Switzerland in 2015.

Based on the guidelines of public corporate governance, the Zurich government council wanted to convert the hospital into a public limited company under private law , initially with the canton as sole owner. The two different roles of the canton, on the one hand the sovereign functions and on the other hand the provision of medical services, should be separated from each other. This provision was written down in the law on the Kantonsspital Winterthur AG (GKSW), with which the law on the Kantonsspital Winterthur of September 19, 2005 (KSWG) was to be repealed and the hospital would be converted from an independent public company into a stock corporation. Left parties and unions held a referendum on the law passed by the Cantonal Council. On May 21, 2017, the electorate rejected the conversion into a stock corporation with a participation of 43 percent. In the same year, the KSW opened a specialist doctor center (FAZ) in the Glatt shopping center in Wallisellen , where special consultations, examinations and minor interventions are offered. In 2018, the outpatient Sports Medical Center Win4 for sports and rehabilitation medicine was opened in cooperation with the company Medbase . As of January 1, 2019, the Cantonal Council released the properties from the canton's centralized real estate management and transferred them to KSW under construction law .

Replacement new building: didymos

Various smaller construction projects were carried out between 1990 and 2005 on the 18-storey high-rise that was moved into in 1968. Nevertheless, in the overall planning in 1988, where the individual clinics, institutes and infrastructure companies were to be suitably housed in the long term and how divided areas were to be merged, it was determined that a replacement of the high-rise was in the offing. In addition to operational, structural, building and fire protection defects, the poor energy balance due to outdated technology and facades caught the eye.

In 2014, the Health Department of the Canton of Zurich commissioned the cantonal building construction department to draw up a feasibility study to identify possible options for renovating the high-rise. In addition to the construction of an extension to the high-rise or the connecting wing and an increase in the east wing, there was also the option of a replacement building. The last option received the best rating for functionality, flexibility and sustainability in a study presented in March 2006. In November 2009 a two-stage project competition was announced . This was won by the RAB planning association Rapp Arcoplan AG from Basel , which planned an elongated nine-storey bed wing under the project name “didymos”, to which a six-storey new treatment wing should connect at a right angle and serve as a link to the existing buildings. For the planned new building, in addition to the high-rise, the temporary oncology facility and the east wing would have to give way. At the meeting on March 2, 2011, the government council decided to further develop the proposal for a construction project with a cost estimate .

On June 18, 2014, the government council approved the construction project as an application for the approval of a loan to the cantonal council. The cantonal council unanimously approved the slightly modified construction project - the east wing originally intended to be dismantled and the garden pavilion will be retained for the time being and an underground car park will be built instead of a planned multi-storey car park - on June 18, 2014 with a property loan of around CHF 349 million. First of all, a separate, four-story new building was built for radio-oncology in the western hospital area, which went into operation in May 2017. The groundbreaking ceremony took place on November 3, 2016 and the main work is being carried out in phases: In the first phase, the temporary structures “Parking Brunnengasse” and “Passerelle Lindstrasse” were created. In the second phase, the new building will be built while the existing high-rise is in operation. After that, the move and the start of operations of the new building will begin in December 2020. In the fourth phase, conversions will take place in the east wing - connection to the bed high-rise building in the basement and conversion to the ground floor connecting wing. Then, around March 2021, the dismantling of the existing high-rise will begin.

literature

- Adolf Max Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976 . Ed .: Health Directorate of the Canton of Zurich. W. Vogel Verlag, Winterthur 1976.

- Adolf Hany: History of the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSW) . In: Government Council of the Canton of Zurich (Ed.): Zürcher Spitalgeschichte . tape 3 , 2000, ISBN 3-905647-98-2 , pp. 203-230 .

- Kantonsspital (Winterthur): 125 years of Kantonsspital Winterthur: Growth and change: Festschrift . Winterthur 2001.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Annual Report 2019 (PDF 5.8 MB) p. 21 f. , accessed on April 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Annual Report 2019 (PDF 5.8 MB) p. 19 , accessed on April 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Key figures 2017: Kantonsspital Winterthur. (PDF; 41.4 kB) In: Federal Statistical Office . Retrieved April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Annual report 2019 (PDF 5.8 MB) p. 2 , accessed on May 25, 2020 .

- ^ Law on the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSWG). (PDF; 140 kB) Canton of Zurich, p. 1 , accessed on January 25, 2020 .

- ^ Law on the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSWG). (PDF; 140 kB) Canton of Zurich, p. 2 , accessed on January 25, 2020 .

- ↑ Organization. Kantonsspital Winterthur, accessed on February 25, 2020 .

- ^ Law on the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSWG). (PDF; 140 kB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 3–4 , accessed on January 25, 2020 .

- ↑ Organigram Cantonal Hospital Winterthur. (PDF; 510 kB) Kantonsspital Winterthur, April 2019, accessed on January 25, 2020 .

- ↑ Research and teaching. Kantonsspital Winterthur, accessed on May 23, 2020 .

- ↑ See the overview: Current Studies. Kantonsspital Winterthur, accessed on May 23, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Lively medical research. Performance report 2019. Kantonsspital Winterthur, accessed on May 23, 2020 .

- ^ Research at the Tumor Center. Kantonsspital Winterthur, accessed on May 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Research at the Breast Center. Kantonsspital Winterthur, accessed on May 23, 2020 .

- ↑ mma: In Winterthur you survive better. Top Online, December 12, 2019, accessed May 23, 2020 .

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 61.

- ↑ a b A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 19-20.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 4.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 3-4.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 4-5.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 10.

- ↑ a b A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 13.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 14-15.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 15.

- ↑ a b A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 30-31.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Voting results of the canton: Takeover of the Winterthur residents' hospital by the canton. Canton of Zurich, accessed on January 30, 2020 .

- ↑ a b A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 32.

- ↑ a b A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 34.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 18.

- ↑ a b c d A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of the Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Kantonsspital Winterthur: 125 years Kantonsspital Winterthur: Growth and change: Festschrift. P. 18.

- ↑ a b c A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 38.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i The history of the Kantonsspital Winterthur. Kantonsspital Winterthur, accessed on January 30, 2020 .

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 85.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 52.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 91.

- ↑ a b Legal texts of the referendums of April 2, 1922. (PDF; 8.1 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 15–18 , accessed on February 2, 2020 .

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 54.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 64.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 60.

- ↑ Cantonal voting results: Expansion of the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital. Canton of Zurich, accessed on February 2, 2020 .

- ↑ a b A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P.56.

- ↑ Referendum of May 5, 1935. (PDF; 13.3 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 14–16 , accessed on February 7, 2020 .

- ↑ Kantonsspital Winterthur: 125 years Kantonsspital Winterthur: Growth and change: Festschrift. P. 32.

- ↑ Cantonal voting results: Extension of the gynecological clinic in the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital. Canton of Zurich, accessed on February 7, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 58.

- ↑ Kantonsspital Winterthur: 125 years Kantonsspital Winterthur: Growth and change: Festschrift. P. 33.

- ↑ a b A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 67.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 82-84.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 58-60.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 94, 116, 119, 121.

- ↑ Referendum of June 25, 1961 (PDF; 16.8 MB) Canton of Zurich, p. 13 , accessed on March 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Referendum of June 25, 1961. (PDF; 16.8 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 18–23 , accessed on March 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Referendum of June 25, 1961. (PDF; 16.8 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 24–25 , accessed on March 1, 2020 .

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 125-126.

- ↑ Referendum of June 25, 1961. (PDF; 16.8 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 25–27 , accessed on March 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Referendum of June 25, 1961. (PDF; 16.8 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 27–28 , accessed on March 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Cantonal voting results: Decision of the Cantonal Council on the approval of a loan for the further expansion of the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital (28 million). Canton of Zurich, accessed on March 2, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c A. M. Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 94-96.

- ↑ Referendum of July 5, 1964. (PDF; 10.4 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 16-17 , accessed on March 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Decision of the Cantonal Council on the creation of a special department for eye patients at the Cantonal Hospital Winterthur (1.7 million). Canton of Zurich, accessed on March 2, 2020 .

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 113 & 115.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 100.

- ↑ Referendum of March 23, 1969. (PDF; 28.0 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 37–40 , accessed on March 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Decision of the Cantonal Council on program and project changes for the expansion of the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital (9.2 million). Canton of Zurich, accessed on March 2, 2020 .

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 98.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 125 & 127.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. Pp. 103 & 116.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 109.

- ↑ a b c d A. Hany: History of the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSW). P. 210.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 133.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 128.

- ^ AM Fehr: 100 Years of Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 101.

- ^ A. Hany: History of the Cantonal Hospital Winterthur (KSW). P. 213.

- ^ A b c A. Hany: History of the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSW). P. 206.

- ↑ Cantonal referendum of September 26, 1982. (PDF; 15.4 MB) Canton of Zurich, pp. 5–7 , accessed on March 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Cantonal voting results: Decision of the Cantonal Council on the approval of a loan for the expansion and renovation of the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital (32.3 million). Canton of Zurich, accessed on March 23, 2020 .

- ^ A b A. Hany: History of the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSW). P. 214.

- ↑ Kantonsspital Winterthur: 125 years Kantonsspital Winterthur: Growth and change: Festschrift. Pp. 49-50.

- ^ A. Hany: History of the Cantonal Hospital Winterthur (KSW). Pp. 206-208.

- ↑ Kantonsspital Winterthur: 125 years Kantonsspital Winterthur: Growth and change: Festschrift. P. 28.

- ^ A. Hany: History of the Cantonal Hospital Winterthur (KSW). P. 216.

- ^ A. Hany: History of the Cantonal Hospital Winterthur (KSW). P. 208.

- ↑ UM Lütolf: Radio-oncology - an important pillar in cancer therapy . In: Kantonsspital Winterthur (Hrsg.): 100 years of radiation therapy - rays for life . Winterthur 2012, p. 44 , doi : 10.5167 / uzh-65292 .

- ↑ The Tumor Center Winterthur meets international quality standards. Kantonsspital Winterthur, October 3, 2018, accessed on March 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Voting result of the Canton of Zurich: Law on the Cantonal Hospital Winterthur (KSZG) of September 19, 2005 (Official Journal 2005, 1013). Canton of Zurich, accessed on March 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Referendum of May 21, 2006. (PDF; 672 kB) Canton of Zurich, p. 2 u. 8 , accessed March 27, 2020 .

- ↑ sda: First prostate operations with robots in Winterthur. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . July 20, 2009, accessed March 29, 2020 .

- ↑ The hospital partnership KSW-Laos is alive and growing! (PDF; 403 kB) In: bazillus. December 2011, p. 14 , accessed on March 29, 2020 .

- ↑ sda: New acute geriatric assessment station. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . December 22, 2010, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ^ Center for radiotherapy in Rüti successfully started. In: Zürcher Oberland / Zürcher Oberland Medien AG. November 14, 2014, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ^ Center for Radiotherapy Zurich-Ost-Linth AG, Rüti (ZRR). In: Commercial Register Canton Zurich. Retrieved April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ srf / sda / horm; morr; kerf; grud: Cantonal hospital and psychiatry do not become public companies. In: Regional Journal Zurich Schaffhausen . May 21, 2017, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Kantonsspital Winterthur AG, owner strategy, definition. (PDF; 67.3 kB) Canton of Zurich, April 12, 2017, p. 1 , accessed on April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Patrice Siegrist: After Zitterpartie: Zürcher are against Spital-AG. In: Tages-Anzeiger . May 22, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2017 .

- ↑ Alexander Lanner: "See us as the central hospital of the country". In: Zürcher Oberland / Zürcher Oberland Medien AG. January 31, 2017, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ KSW: New specialist medical center with a feel-good factor. In: Medinside. January 31, 2017, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Migros subsidiary Medbase and Kantonsspital Winterthur are planning a medical center. In: Medinside. April 27, 2016, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Annual report 2018: Trend reversal and record year - but the challenges remain great. Kantonsspital Winterthur, April 15, 2019, accessed on April 20, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Kantonsspital Winterthur, replacement high-rise building "Didymos", new building and renovation, Brauerstrasse at 15, 8400 Winterthur. In: Building Department, Building Department, Canton of Zurich. Retrieved April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ 225. Winterthur Cantonal Hospital (replacement high-rise building, project planning). (PDF; 37.2 kB) In: Excerpt from the minutes of the Government Council of the Canton of Zurich (meeting on March 2, 2011). Pp. 1–3 , accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ 703. Approval of a loan for the replacement high-rise building of the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital, subproject 1, new buildings. (PDF; 27.3 kB) In: Excerpt from the minutes of the Government Council of the Canton of Zurich (meeting on June 18, 2014). P. 1 , accessed on April 18, 2020 .

- ^ Resolution of the Cantonal Council on the approval of a loan for the replacement high-rise building for the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital, subproject 1 - New buildings. (PDF; 61 kB) In: Cantonal Council of Zurich. Retrieved April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Voting result of Zurich City Hall: Approval of a loan for the replacement high-rise building of the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital, sub-project 1 - New buildings. (PDF; 111 kB) In: Canton of Zurich. March 2, 2015, accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ sda: New buildings at the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital are making headway: operations in "Haus R" started. In: Limmattaler Zeitung . May 31, 2017, accessed April 18, 2020 .

Remarks

- ↑ Exceptions were made for building projects, cf. AM Fehr: 100 years of the Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 61.

- ↑ In some cases, Hans Conrad Brunner is also called Hans Konrad Brunner, cf. AM Fehr: 100 years of the Winterthur Residential and Cantonal Hospital 1876–1976. P. 76. However, he is listed in the register of the University of Zurich as Hans Conrad Brunner, cf. Matriculation number 23959 . The State Archives of the Canton of Zurich omitted the nickname Hans entirely and only wrote about one Conrad Brunner, cf. the Archives Kantonsspital Winterthur KSW, 1914–2000 (fund) of the State Archives Zurich.