Marxist philosophy

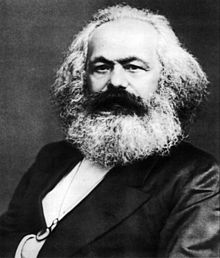

Marxist philosophy describes the philosophical assumptions of the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels . All later philosophical conceptions that refer to Marx and Engels are also included in this.

The question of whether a Marxist philosophy even exists is controversial. While z. B. Benedetto Croce declares that Marx was ultimately about replacing philosophizing with practical activity, and one could therefore not speak of a philosopher Marx and consequently not of a Marxist philosophy, Antonio Gramsci defends the legitimacy of the term "Marxist philosophy" , since even the negation of philosophy is not possible other than philosophizing. Leszek Kołakowski, on the other hand, advocates the thesis that Marxism should primarily be viewed as a "philosophical project" "which was made more precise in economic analyzes and political doctrine".

Friedrich Engels summarized the scientific achievements of Karl Marx in his funeral speech in two essential discoveries: "Like Darwin discovered the law of the development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history : ...; that is, the production of immediate material means of subsistence and with it Each time a people or a period of economic development forms the basis from which the state institutions, legal beliefs, art and even the religious ideas of the people concerned have developed, and from which they must therefore also be explained - not, as has been done up to now , vice versa.

On top of that. Marx also discovered the special law of motion of today's capitalist mode of production and the bourgeois society it creates. With the discovery of added value, light was suddenly created here ... "

Marxist thought spread in a variety of ways. It first developed its effect in the labor movement . It was worked out by Lenin and Stalin into the doctrine of the Communist Party . But it was also adapted in their own way in China and the Third World. After the Second World War, the neo-Marxists took up the ideas of Marx and Engels in a new form and combined them with those of other thinkers such as B. Edmund Husserl , Martin Heidegger and Sigmund Freud . After the collapse of the Soviet Union , post-Soviet Marxism developed primarily in Russia .

Object definition

Due to the most varied of interpretations regarding the existence, content and purpose of a Marxist philosophy, no general characteristics of a Marxist philosophy can be determined. Determining the relationship between Marxist theory and philosophy is also made difficult by different understandings of Marxist theory. The role of Engels, the theoretical relationship between Marx and later Marxisms, and the question of a Marxian early and late work and its significance should be mentioned as paradigmatic conflicts. Karl Korsch summarizes the relationship between Marxist theory and philosophy in three basic positions:

- It is criticized that Marxist theories have no (decisive) philosophical content

- It is positively emphasized that Marxist theories have no philosophical content

- The shortcoming is emphasized that Marxist theories have no philosophical content

He formulates a fourth point of view:

- Marxist philosophy is a critique of bourgeois philosophy based on materialist dialectics for the purpose of class struggle

The article summarizes Marxian thinking as a fundamentally philosophical view of man and the world, historical and economic theory and a political program. These elements are closely interwoven. Karl Marx hardly developed his philosophical approaches systematically. His main interest was the critique of political economy and the analysis of a "given period of society". Marx did not use purely descriptive methods, but repeatedly presented the political and economic conditions he criticized as expressions of materialistic - dialectical laws of development and necessities.

Philosophy term

Influences from the history of philosophy

Hegel

Marx's thinking is essentially influenced by the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel , from which he takes central basic terms and concepts and develops them further in his own materialistic way. These include a. the method of dialectics , the thought of alienation , the conception of work and the assumption that the human being is a social being.

Marx emphasizes that Hegel first presented the method of dialectic in its “general forms of movement in a comprehensive and conscious way”. However, as the bearer of the dialectic, Hegel saw an “absolute, ie superhuman, abstract spirit” at work. Marx, on the other hand, wants to position man and nature as the real subjects of history.

Marx also found the idea of alienation in Hegel - albeit also as an “alienation of the spirit”: “The 'unhappy consciousness', the 'honest consciousness', the struggle of the 'noble and mean consciousness' etc. etc., these individual sections contain the critical elements - but still in an alienated form - of entire spheres, such as religion, the state ”.

Marx also adopts Hegel's insight into the crucial importance of work for the development of human self-awareness. The “great thing ” about “ phenomenology ” is “that Hegel grasps the self-generation of man as a process” and “preserves the objective man because he understands real man as the result of his own work”. However, the "work that Hegel alone knows and recognizes [..] is abstractly spiritual".

The idea of the social nature of man represents a further point of reference to Hegel. Marx criticizes, however, that in Hegel “family, civil society, state etc. are determinations of the idea”. The real social structures are not expressed in their reality, but “as appearance, as phenomenon”.

Feuerbach

Of Ludwig Feuerbach , Marx takes over its religion and philosophy criticism , according to which philosophy "is nothing but, brought in thought and thinking executed religion "; He describes religion as a “form and mode of existence of the alienation of the human being”. Like Feuerbach, Marx also makes people the starting point for all of his thinking. However, he criticizes Feuerbach for one-sidedly understanding people as individuals. Feuerbach knows “no other 'human relationships', 'man to man', other than love and friendship, and indeed idealized”; he does not see “that the abstract individual he analyzes belongs to a certain form of society”.

In contrast, Marx regards social relationships as constitutive for man. Because “the human being is not an abstract being crouching outside the world. The human being, that is the human world, the state, society ”.

Philosophy and practice

In the eleventh Feuerbach thesis, Marx reproaches “the philosophers” for having only interpreted the world in different ways while the point is to change it. He emphasizes that it is not a question of “just bringing about a correct awareness of an existing fact”, but “overturning this existing fact”.

Marx's criticism is v. a. the speculative idealism of Hegel . His goal is not to reject theory and philosophy at all, but rather to "negate the philosophy of that time, of philosophy as [mere] philosophy". Like Hegel, Marx is also concerned with the “becoming real of the rational”, but for him this can only happen through practical revolutionary action. The mere knowledge of reality is not enough for this; for that “the rational is real, proves itself precisely in the contradiction of the unreasonable reality, which is everywhere the opposite of what it says and the opposite of what it is”.

For Marx, philosophy is a weapon in the struggle to reorganize human living conditions. It is "the philosopher in whose brain the revolution begins". That is why “the proletariat finds its spiritual weapons in philosophy”. However, the realization of philosophy ultimately means that it loses its present essence, to be pure theory and is transformed into practice: "its realization [is] at the same time its loss". Marx is concerned with “turning into a practical relationship to reality”. With the “becoming worldly” of philosophy, the “end of speculation” is finally reached. All that remains is the empirical sciences : “Where speculation ends, in real life, real, positive science begins, the presentation of practical activity, the practical development process of people. [...] Independent philosophy loses its medium of existence with the representation of reality. At most a summary of the most general results that can be abstracted from the consideration of the historical development of human beings can take its place ”.

Criticism of religion

The criticism of religion is, for Marx, "the premise of all criticism." The task of philosophy must be the emancipation “from all heavenly and earthly gods”.

Marx adopts the approach of Feuerbach's criticism of religion - especially his alienation thesis and sensualism . Feuerbach had argued that religion leads to a “division of man with himself”; the human being posits himself to God "as a being opposite to him", without the "barriers of the individual (real, bodily) human being". He should pay attention to this in prayer and sacrifice and thereby withdraw his powers from the real human species.

Feuerbach's sensualistic approach aims to rehabilitate sensuality: "Only a sensual being is a true, a real being". Only through the sensual relationship to the object can a person recognize truth and reality and gain self-confidence. For Marx, Feuerbach's work "essentially puts an end to the critique of religion". Unlike Feuerbach, he sees the actual reason for religious self-division not in the human desire for infinity, but in an “untrue” reality that underlies individual consciousness and striving: in the state and in society. These "produce religion, an inverted world consciousness, because they are an inverted world". The “worldly narrow-mindedness” must be criticized and overcome as the real cause of the religious division. The demand of Feuerbach's criticism of religion that man must “give up the illusions about his condition” is reversed by Marx into the “demand to give up a condition that needs illusions”. For Marx, the critique of religion essentially becomes a critique of law, and the critique of theology becomes a critique of politics.

However, criticism of religion does not become completely superfluous; there is “a difference between political and human emancipation”. Political emancipation describes the granting of human and civil rights in the constitution. In doing so, the state abolishes religious privileges, but does not affect private life and individual religious awareness. But even political emancipation itself remains a religious one: "The state is the mediator between man and man's freedom", and for Marx religion is precisely the recognition of man through a mediator. Human emancipation is only achieved when the “individual person takes the abstract citizen back into himself” and “no longer separates the social force from itself in the form of political force”.

According to Marx, even the “old”, idealistic philosophy was not in a position to overcome religious alienation. On the contrary, it was "the religion brought into thought and thoughtfully executed". It must be replaced by a new philosophy that represents the “head” of emancipation. The “heart” is the proletariat, the only class that is able to overcome the “previous world order”. Its historical task is to “overturn all conditions in which man is a humiliated, enslaved, abandoned, contemptible being”.

Religion and capitalism

From Marx's point of view, religious consciousness - especially in Christianity - is related to the capitalist mode of production : "For a society of commodity producers [...] Christianity with its cult of abstract man [...] is the most appropriate form of religion". He compares the mediator role of money to that of Christ . As in Christianity, where the “mediator now becomes the real God” and his “cult” “becomes an end in itself”, money also becomes the mediator between objects and people in capitalism. The commodity money develops into a " fetish ". It demands submission and sacrifice from its author and appropriates his life.

Only when people in free socialization bring production under their conscious, systematic control and the production process is no longer mystical and overwhelming, the “religious reflection of the real world” (Marx) or the “religious reflection of foreign power” (Engels) can disappear .

The human being

The importance of work

Essential for Marx's understanding of man is his concept of work . It is "the proven being of man". In creative work man can experience himself in his creative power and the belief in a divine world creator can be exposed as alienation and loss of self. In numerous passages of his work, Marx describes the fundamental importance of work with poetic power: it is “the fire that creates life”, the “flame that brings life” and it awakens things “from the dead”.

According to Marx, work is a sensual, objective relationship. In it a social subject grasps an initially natural thing and works on it. Both subject and object change in this process. The subject unfolds itself in its abilities and powers by impressing its will on the object and objectifying itself in it. The object, on the other hand, takes on a new shape through the influence of the subject and is quasi "humanized". This process is driven by the sensual neediness of the human being experienced as “suffering”. Through productive work , man creates the objects that are necessary to satisfy his needs. The sensual need of man is ultimately also the motor of human history. The satisfaction of needs is not limited to material objects. The first and last need is the person himself. The wealth created “under the presupposition of socialism ” does not cancel out this need, on the contrary: “The rich person is at the same time the person who needs a totality of human expression”.

Sensuality connects people with one another and with nature. People experience themselves in sensual encounters with the other person. It is conveyed through social work and the exchange of objective products. Sensuality, Marx argues, is a specifically human quality. People want to live as people, which also requires culture. However, this is not a separate area compared to material-sensual life practice and is therefore part of the " superstructure ". There is therefore no original, independent spiritual need.

The importance of nature

In the processing of the natural substance, man and nature grow together into a dialectical unit and each reach a higher level of their existence. Man becomes more or less an “object” himself, nature becomes “man”, as Marx put it to the point. In the created product the unity of nature and man is complete. Marx expresses this in “ Capital ” in a formulation that is strongly reminiscent of the Aristotelian act - power theory: “The process expires in the product […]. The work has connected with its subject. It is objectified and the object is processed. What appeared on the part of the worker in the form of restlessness now appears as a dormant quality, in the form of being, on the part of the product ”.

The dialectical unity of producer and product is made possible by the unity of man and nature that lies ahead. Man is “part of nature”. The "whole so-called world history" is basically nothing other than "the becoming of nature for man". The movement of nature remains immanent in it. Its aim is not, as was the case with Hegel, a spiritualization that nullifies sensuality. Rather, it leads via alienation to the perfect unity of nature in society: "Society is the perfect essential unity of man with nature, the true resurrection [resurrection] of nature, the naturalism of man and the humanism of nature".

freedom

Freedom is thought of by Marx as a relationship of the individual to society: “Only in community [with others does each] individual have the means to develop his talents in all directions; it is only in the community that personal freedom becomes possible ”. Everyone needs the other in order to be himself: his products but also the other as human, because human is the first need for human. Only the relation to the other enables one's own self-development. This self-development to the "total", i. H. full social individual is the essential moment of freedom.

In addition, Marx emphasizes, freedom can only be conceived in concrete terms: it takes place in production. In this context he turns against Adam Smith , who equated work with “curse”, freedom with “rest”. “Overcoming obstacles” means “exercising freedom”. In it the individual sets "external purposes", which means "self-realization, objectification of the subject, hence real freedom".

After all, freedom is the goal of communism . Marx emphasizes how much freedom is tied to a high level of the productive forces: “Indeed, the realm of freedom only begins where work, which is determined by need and external expediency, ends; it is, therefore, of the nature of the thing beyond the sphere of actual material production ”. "True freedom" is realized where one's own creative power is freed from the compulsion to have to choose between given alternatives and to follow self-set goals. However, material production is always presupposed as its “basis”, which Marx calls the “realm of necessity”: “But this always remains a realm of necessity. Beyond this begins the development of human strength, which is an end in itself, the true realm of freedom, but which can only flourish on that realm of necessity as its basis ”.

For Marx, freedom in civil society is primarily a negative form of freedom. As "personal freedom" it means separation from others in order to keep open spaces in social life. In it the individuals become independent through their separation from one another. It is "the freedom of man as an isolated, withdrawn monad ". The civil " human right to freedom is not based on the connection between people and people, but rather on isolation".

According to Marx, “only under the rule of Christianity, which makes all national, natural, moral, theoretical relationships external to man (...) could civil society completely separate itself from state life, tear all genre ties of man, egoism, selfish need put the place of this generic bond, dissolve the human world into a world of atomistic, hostile opposing individuals ”.

The pattern of negative freedom in the bourgeois world is "free competition". Marx describes it as "the most complete abolition of individual freedom and the complete subjugation of individuality under social conditions that take the form of factual powers, even of overpowering things [...]." "Individuals are not set free in free competition; but capital ”.

ethics

Ethical questions only play a very subordinate role in Marx's thinking. For him, the goal of a “human community” is not a postulate of an inhuman, capitalist society, but a force that is contained in it and that will necessarily be realized: “Faith, specifically the belief in the 'holy spirit of the community' is the last thing that is required for the implementation of communism ”. The working class “has no ideals to realize; it only has to set free the elements of the new society which have already developed in the womb of the collapsing bourgeois society ”.

Moral ideals that are not “the theoretical expression of the practical movement” and thus do not correspond to the historical state of a society must remain “more or less utopian , dogmatic, doctrinal”. If the “material elements of a total upheaval” are not present, “it is completely irrelevant for practical development whether the idea of this upheaval has already been expressed a hundred times”. Like all spiritual phenomena, “morality” is “a special mode of production” and “falls under its general law”.

Marx does not know the phenomenon of guilt . The action of the capitalist , which appears as his “individual mania”, is in reality “the effect of the social mechanism in which he is only a driving wheel”. In communist society, too, the question of moral ought does not arise. Here the unity of man and nature is achieved. How to act then results from "humanized nature" itself.

Society

Individual and Society

Marxist anthropology regards the relationship of the individual to human society as central. Marx goes far beyond Aristotle's definition of man as a “ zoon politikon ”. The relationship with others is not only essential for the individual; Rather, it is only through this relationship that it becomes what it is: “The human being is not an abstraction inherent in the individual individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of social conditions ”. Thus Marx takes a naturalistic view of society: it is "the true resurrection [resurrection] of nature". Wherever man intervenes in nature in a changing way and thus expresses himself, he does so as a social being. Society is therefore “the perfect essential unity of man with nature”.

To be sure, according to Marx, sociality is the essential characteristic of man; but for him the concept of essence has no metaphysical , but a natural dimension. The relationship between people and society is expressed in the “exchange of both human activity within production itself and of human products against one another”. In the end, social relationships arise “through the need and egoism of individuals”.

Although Marx assigns society a fundamental importance for the development of the individual, he still refuses to speak of society as a superordinate and independent entity . “Above all, one should avoid fixing 'society' again as an abstraction in relation to the individual. The individual is the social being ”. Society is not separated from individuals, but only appears in the relationships between them: "Society does not consist of individuals, but expresses the sum of the relationships, relationships in which these individuals stand to one another".

The class concept

According to Marx, every society since primitive society is divided into classes . For belonging to a class, what is “objectively” decisive is the commonality of economic living conditions, the way of life, interests and education of its members. But only when a class becomes aware of itself and develops a corresponding class consciousness , it constitutes itself as the class that it is and is thus enabled to fulfill its historical mission.

Class struggle

For Marx and Engels "(since the dissolution of the ancient common property of land) the whole story has been a history of class struggles ". The irreconcilable struggle between the ruling class and the ruled class is the driving force of historical development. At the same time, it represents the decisive step for the self-confidence of the ruled class: in it “this mass comes together, it constitutes itself as a class for itself”.

In the course of the conflict, which grew up to the revolution, a rising class took over the rule of the state and society on a “higher” socio-historical level. Only with the revolutionary elimination of the last ruling class, the bourgeoisie, by the proletariat, does the gradual transition to a classless society take place under socialism with the help of the dictatorship of the proletariat .

Division of labor and social development

The association in the historical form of class society is created for Marx and Engels already in the biological constitution of man. This does not allow him to exist alone and refers him to the opposite sex. This leads to an “increase in population”, from which follows an “increase in needs” and “increased productivity”. The division of work within the family becomes a social division of labor , which finally becomes a reality from the moment "when a division of material and intellectual work occurs".

The incipient division of labor means at the same time the emergence of private property, because "division of labor and private property [are] identical expressions - in the one the same is said in relation to the activity what is stated in the other in relation to the product of the activity". “Enjoyment and work, production and consumption” now fall to “different individuals”. There is a “separation of society into individual, opposing families” and an “unequal, quantitative as well as qualitative distribution of labor and its products”.

With the emergence of private property, the originally communal “exchange of products” becomes “barter trade”. This determines all human "forms of communication" in civil society. Marx knows no area that is excluded from it: "Individuals face each other only as owners of exchange values , as those who have given themselves an objective existence for one another through their product, the commodity" and only exist "factually for one another". Only with the abolition of private property will the mutual treatment of people as a thing slowly be transformed into the “intercourse of individuals as such”. With this in mind, Marx writes in his Critique of the Gotha Program :

“In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaved subordination of individuals to the division of labor, so that the opposition between mental and physical labor has also disappeared; after work has become not only a means to life but itself the first necessity of life; After the all-round development of individuals, their productive forces have grown and all the springs of the cooperative wealth flow more fully - only then can the narrow bourgeois legal horizon be completely exceeded and society can write on its banner: everyone according to their abilities, everyone according to their needs! "

The money ratio

With the transformation of labor into commodity, real human relationships are replaced by money. In bourgeois society, “no other bond is left between man and man than bare interest, than the callous 'cash payment'”. Money is the “alienated ability of humanity” to relate to one another. Marx describes it as the “bond of all ties”, the “general whore” and “matchmaker of people and peoples”. Whoever owns it can exchange “the whole human and natural objective world”.

Money can turn all relationships between people upside down: “It transforms fidelity into unfaithfulness, love into hate, hate into love, virtue into vice, vice into virtue, the servant into the master Lord in the servant, the nonsense in mind, the mind in nonsense ”.

Being and awareness

Base and superstructure

Thinking, emphasizes Marx, is essentially determined by its "material foundations", the social practice of the individual. He summarizes this in the well-known “ basic superstructure ” thesis: “It is not the consciousness of people that determines their being, but, conversely, their social being that determines their consciousness”. Marx expressed this view several times in different formulations, for example he also wrote “It is not consciousness that determines life, but life determines consciousness”, or “Consciousness can never be anything other than conscious being, and the being of people is their real life process. "The entire human reality is therefore determined by the" production and reproduction of real life ":

"The people are the producers of their conceptions, ideas etc., but the real, active people, as they are conditioned by a certain development of their productive forces and the same corresponding intercourse [note: production relations] up to its widest formations."

These "broadest formations" are the so-called intellectual modes of production or the superstructure. "Religion, family, state, law, morality, science, art etc. are only special modes of production and fall under their general law". Law is, for example, “only the will raised to law” of the ruling class, “a will whose content is given in the material living conditions” of this class. In bourgeois society, the decisive relationship of production is private property. It contributes significantly to the contradictions of consciousness and the alienation of people.

Objections raised against this thesis prompted Marx and Engels to state that there was a mutual influence between the two areas of base and superstructure. In the “last resort”, however, as Engels emphasizes, in the intellectual history “the economic conditions”, the “decisive” ones, which “form the continuous red thread that alone leads to understanding”.

The "wrong" consciousness

The bourgeois consciousness is characterized by the fact that it does not want to admit its own social conditions. It is subject to self-deception about the universal validity of its forms of consciousness such as “ morality , religion, metaphysics ”, which, like the “bourgeois ideas of freedom, education, law, etc.” are “products of bourgeois production and property relations”. The bourgeoisie regard their ideas “like all the submerged ruling classes” as “eternal natural and rational laws”.

Marx calls this type of self-deception " ideology ". It is “identical with the false consciousness or the thought process, which experiences a mystification in the consciousness in such a way that the person does not know the forces that really guide his thinking and imagines the pure consistency of the thought itself or of purely thought influences to be guided ”.

The "false consciousness" is typical of every class society . The respective ruling class has an interest in presenting the existing conditions as objective and generally applicable. In this respect, their ideology is at the same time false but also necessary consciousness, not necessarily in an epistemological , but in a practical sense, i. H. every new social order represents a step forward over the previous one. In this respect, the thinking shaped by capitalism is a step forward on the way to communism. On the other hand, the bourgeoisie, with the means of power at its disposal, can make its own ideology the thought of the oppressed classes; because: “the thoughts of the ruling class are the ruling thoughts in every epoch”.

Marx and Engels each attribute their own class consciousness to the various social classes . Only the “class-conscious” proletariat no longer has “false consciousness”. Since it has no rights and no property, its consciousness is no longer focused on the defense of particular privileges, but on the realization of humanity and the “recovery of man”.

See also: criticism of ideology

The economy

→ Main article: Marxist economic theory

The Marxian representation of the functioning of the capitalist economy in his main work " Capital " can be understood from a perspective determined by philosophical interests. For Kolakowski it is "not a separate area that can be understood and presented independently of his anthropological inspirations and independent of the historical philosophy", but rather represents the "application of the theory of dehumanization to the relationship between production and exchange phenomena".

Value theory

Historical starting points

The economic theory of value - the roots of which can be traced back to Plato - deals with the problem of the exchange of goods: What is the common property of goods that makes it possible - despite all qualitative differences - to compare them quantitatively and to exchange them for one another ? Plato and Aristotle already developed the idea that the value of a commodity is measured in the time needed to manufacture it. The representatives of classical economics Adam Smith and David Ricardo worked on the theory of value with the aim of an objective calculation of profits and the mechanisms of their distribution.

Karl Marx's theory of value, on the other hand, is based on the question of the nature of exploitation in a society based on private property. Like the thinkers mentioned above, Marx also regards labor as the only measuring instrument for determining the value of goods; he also sees it as the only source of value. According to Marx, the phenomenon of exchange value itself is not a natural and inescapable property of social life, but a historical transitional form. The future communist society would accordingly no longer need exchange value, as it has not always existed in history.

The double form of value

According to Marx, every commodity can be viewed under two aspects:

- with regard to their qualities, for example as linen, chair or bread, which satisfy human needs: this aspect he calls the use value .

- with regard to the fact that it is interchangeable with every other thing in a certain quantitative relation: this aspect he calls the exchange value .

A thing can only assume an exchange value if it is to be exchanged for another thing and only becomes a commodity when it is produced for exchange and incorporated into the system of commodity exchange. Exchange value or the “commodity form”, as Marx also called the phenomenon, is not a property of the thing “in itself”. The form of goods only exists in societies in which people compare their products and face each other as private owners:

“All goods are non-use values for their owners, use values for their non-owners. So you have to switch hands on all sides. But this exchange of hands forms their exchange, and their exchange relates them to one another as values and realizes them as values. The goods must therefore be realized as values before they can be realized as use values. "

The money form

If all products reveal their value only in exchange, then each individual product can also be the measure for all others. With the market, money emerged as the commodity which, due to its natural properties, was given a privileged position as a measure of value. In terms of its character as exchange value, money is no different from other commodities; like them it is the product of the abstract labor of man. Exchange value becomes independent in money and takes on a form that disguises its origin in work.

The double form of work

The double form of the value of commodities arises from a double form of labor. Following Plato, Marx therefore differentiates between two aspects of the work process:

- the concrete work that produces the use value of a commodity and

- the abstract labor that creates its exchange value.

The abstract work is the different work - z. B. the baker, spinner, woodcutter, etc. - makes comparable with each other. Their common denominator is the expenditure of labor within a measurable time as part of the social division of labor. In this way, all forms of work, no matter how complex, are reduced to the socially necessary working time as a measure of value. The decisive factor is not the time actually used, but the socially necessary time, i.e. H. the average time required to manufacture an object under certain production conditions and with a certain level of human abilities.

The commodity fetishism

The money and commodity forms that objects assume in a capitalist society are sources of a specific delusion that Marx calls commodity fetishism . The exchange value character of things appears as their superhistorical, natural property, but is actually an appearance. In the act of exchange mediated by money, people unintentionally agree that their personal abilities no longer belong to them, but to the objects in which the exchange value they produce is contained. The value-creating workers are degraded to the apparent “object” of labor who produce goods for the “subject”. The commodity producers are ruled by their products: "For them their own social movement takes the form of a movement of things under whose control they are instead of controlling them".

Reification

By “ reification ” Marx and Engels understand the transformation of objects or human labor into “things”. In capitalism, use value takes a back seat, while exchange value makes everything a commodity and thus a thing.

Theory of exploitation and alienation

The value of labor is also determined by the time it takes to produce and reproduce it. The labor force is therefore comparable to any commodity. Their value is measured by the value of the products that

- on the one hand for the rearing and training of the worker (the longer the training, the greater the value of the worker),

- on the other hand are necessary to maintain the labor force of the worker and to found and support his family.

The phenomenon of exploitation consists in the fact that “ living labor ” generates a significantly larger amount of exchange value than the products necessary for its reproduction are worth. Marx calls this difference the surplus value . The use value of labor is based on the fact that it creates an exchange value that exceeds its own exchange value. As in every act of purchase, the seller of the goods "surrenders" the labor power of their use value, i. that is, he makes them available to the “capitalist” and thus “realizes” their exchange value. The use of the commodity labor consists in the application of “muscles, brains and nerves”, but a plan given by the capitalist is assumed. “Independent thinking” is not part of the labor force but of the productive force .

The material processing of objects through living labor thus represents the only source of value. His analysis that man's labor is a commodity leads Marx to the assumption that the worker is degraded to a "thing". He has to sell his qualities and skills to a third party in order to secure the necessary “food”: “He works to live”. “It is no longer the worker who uses the means of production , but the means of production that use the worker. Instead of being consumed by it as a material element of its productive activity, they consume it as a ferment of their own life process, and the life process of capital consists only in its movement as a self-utilizing value ”.

Capitalism consequently separates the product of labor from labor in that the product is the property of the capitalist. The worker is indeed the creator of values, but can only appropriate them as use values and increase his own "wealth of life" if he can pay the capitalist the price for these use values. Because of this separation of work and property, the cooperation in the production process cannot lead to any commonality between “worker” and “capitalist”. The social character of work is therefore class-wise separated under capitalist conditions .

The history

Historical materialism

→ Main article: Historical materialism

Understanding the course of history and being able to master it through this understanding is the central concern of Marxism: "We only know one single science, the science of history ". The view of Hegel, who had seen history as a "development process of humanity itself", "whose inner regularity through all apparent contingencies now became the task of thinking to prove" was of decisive influence.

Marx and Engels, however, oppose what they consider to be the “logical, pantheistic mysticism ” of Hegel. Hegel did not make the person but the "idea" the true designer of history. Thus people “owe their existence to a different spirit than theirs; they are provisions set by a third party, not self-determination ”.

Although Marx complains to Hegel that man is the creator of his own history, he sees the historical process at the same time determined by material necessities. The “ultimate end purpose” of his analyzes in “Capital” is “to reveal the economic law of motion of modern society”, which for him represents a “law of nature”. He compares his approach with the physicist's observation of natural processes. Marx considers the course of history to be essentially determined by three necessities:

- the tradition , d. H. the traditional behavior of "all dead generations": it weighs "like a nightmare on the brains of the living".

- the resources available , d. H. "The existing productive forces " and the "formation of a revolutionary mass".

- the instinctual striving to maintain existence : "In order not to lose the fruits of civilization, people are forced, as soon as the manner of their intercourse no longer corresponds to the acquired productive forces, to change all their traditional forms of society".

The individual acts as the bearer of certain class relationships and interests that assert themselves against him as “compulsory laws”. Driven by the dialectic of alienation and the class struggle, history is “necessarily” moving towards the proletarian revolution . The individual events within this process can be entirely random; However, they “fall into the general course of development themselves and are compensated for by other coincidences”.

The existing productive forces play a decisive role in the course of history. Marx and Engels emphasize: "All collisions in history have their origin, according to our view, in the contradiction between the productive forces and the form of intercourse". The concept of productive force is used ambiguously. While Marx uses it in “Capital” in a purely “objective” sense and equates it with the measurable magnitude of labor productivity, he understands the expression elsewhere as a subjective ability: “Every productive force is an acquired force [...] the product of previous activity . The productive forces are therefore the product of the applied energy of man ”.

The Marxist philosophy of history is generally known today under the term " historical materialism ", which was coined in 1892 by Friedrich Engels. But Engels mostly used the term "materialistic view of history". In the further discussion of Marxism, both terms initially existed side by side, until after the Second World War, under the influence of Stalin, the expression “historical materialism” became predominant.

The communist society

The goal of human history is communist society, which is necessarily reached because of the lawful advance of the productive forces. In contrast to many early socialists , Marx and Engels forego a clear description of the “new society”. Their statements mostly remain abstract and formal and are largely limited to contrasting the imperfections of capitalist society with communist ones.

The communist society builds on the previous story, but at the same time represents a radical new beginning: "People build a new world [...] from the historical achievements of their declining world". One of the great achievements of capitalist industrial society is v. a. the universal development of the productive forces. It already contains "in itself, only in the wrong, upside-down form [...] the dissolution of all narrow-minded prerequisites of production". Because of its own contradictions, capitalism will cancel itself out: the “ universality ” towards which capital “is inexorably driven will find limits in its own nature which, at a certain stage of its development, allow it to become recognized as the greatest barrier to this tendency therefore drive it to abolish it ".

The “high degree” of the development of the productive forces is an “absolutely necessary practical prerequisite” for communist society. Without it, “only the deficiency would be generalized”. With the all-round development of the productive forces in capitalism goes hand in hand with the universal development of the proletarians, which is a necessary condition for the communist revolution.

The transition to the "new society" is only possible through the abolition of private property with which at the same time the abolition of "human self-alienation" and the "real appropriation of the human being by and for people" takes place. Appropriately"; everyone can make use of all the appropriate means of production and develop their skills and needs. Humans cease to be “the mere bearer of a detailed social function” and thus only “partial individual”. He becomes a “totally developed individual for whom different social functions are modes of operation that replace one another”.

One of the few vivid descriptions of the communist future society can be found in the “German Ideology”, where it is described as a society in which “everyone does not have an exclusive sphere of activity, but can develop in any branch of society regulates general production and makes it possible for me to do this today, that tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, to raise cattle in the evening, to criticize after dinner, how I feel like, without ever hunter, fisherman, To become a shepherd or a critic ”.

The distinction between work and life, which is characteristic of the capitalist world, is abolished in communist society. Work has "become itself the first necessity of life"; the “contrast between mental and physical work has disappeared”. Marx and Engels postulate the connection between "work and enjoyment" for the new society. The work becomes “a means of liberating people. By giving each individual the opportunity to develop and exercise all their abilities, both physical and spiritual, in all directions, and in which they turn a burden into pleasure ”.

In communist society the state will also cease to exist: “Society, which reorganizes production on the basis of free and equal association of producers , moves the entire state machine to where it will then belong: to the museum of antiquities, next to the spinning wheel and the bronze ax ”. Where the state ceases to exist, there are no more laws passed by it; each individual becomes a “legislator” himself. What remains in the new society are only “simple administrative functions”, which, however, no longer have any similarities with the “power of the state”.

In communism, a completely new relationship will arise between man and nature, for which there is no “evidence in the existing”. On this point, communism will leave previous history entirely behind. There will be a "perfect essential unity of man with nature"; Nature is no longer treated one-sidedly as an object of use or exchange, but is understood in its integrative unity with humans. Only through the new relationship between humans and nature is their human face fully visible.

sense

The express question of the meaning of life does not arise in Marx. It is indirectly posed by him in the question of the meaning of history: "What is the meaning in the development of mankind, does this reduction of most of mankind to abstract work?" Marx sees the sense of alienation and self-loss of the greater part of humanity in the “development” towards the goal of communism. This goal gives meaning to the entire historical movement; In this context, Marx speaks of the “absolute movement of becoming”. This movement takes place in the dialectic of the class struggle, in which both parties are necessary and in this respect meaningful. The members of the revolutionary class ( proletariat ) constitute the new society, but this would not be possible without the existence of the reactionary class ( bourgeoisie ) antagonistic to it.

For Marx and Engels, “progress” towards communism has a twofold face: misery and death of the one is the condition for the life of the other; "The anarchy of production, the source of so much misery, [is] at the same time the cause of all progress". Those who have been run over by the “wheel of history” can only find the meaning of their life if they succeed in understanding the inner necessity of the dialectical historical process and their part in it. The ambivalence of progress will only be resolved under communism:

“Only when a great social revolution has mastered the results of the bourgeois epoch, the world market and the modern productive forces, and subjected them to the common control of the most advanced peoples, will human progress no longer resemble that hideous pagan idol that the Wanted to drink nectar only from the skulls of the slain. "

Cycle of life and death

For Marx and Engels, the life of the individual, but also of humanity as a whole, is permeated with impermanence. Marx takes over from Lucretius the formula of the “immortality of death” as the “substance” of nature. The death is an "essential element of life," he is a " negation of life," "substantially contained in life itself." The development of life and human history ultimately boils down to an "eternal cycle" from which human life emerges only to submerge again. This is how Engels writes in the Dialectic of Nature :

“However, 'everything that arises is worth it to perish'. Millions of years may pass over it [...] but the time moves inexorably, [...] where the last trace of organic life gradually disappears and the earth, a parched, frozen ball like the moon, in deep darkness and in ever narrower orbits circles around the likewise dead sun and finally falls into it […] It is an eternal cycle in which matter moves […] But how often and how mercilessly this cycle takes place in time and space; however many millions of suns and earths may arise and pass away [...] we have the certainty that matter remains forever the same in all its changes, that none of its attributes can ever be lost, and that it therefore also has the same iron necessity with which it is on earth its highest blossom, the thinking spirit, will be exterminated again, must regenerate it elsewhere and in another time. "

Dialectic of history

The course of human history is characterized by the principle of dialectic. It is a development whose “unity is established through its opposition”. The decisive contradiction in the historical process is that between private property that has become wealthy and the proletariat: “The proletariat and wealth are opposites. As such, they form a whole. They are both forms of the world of private property ”.

Yet, according to Marx, "it is not enough to explain them as two sides of a whole". The two opposites are mutually dependent and cannot exist without the other: “Each reproduces itself by reproducing its other, its negation”.

Private property represents the “positive side” of the opposite; it tries to sustain itself. The proletariat, on the other hand, embodies the “negative side” of the antithesis by trying to abolish private property. As the development of private property advances, the proletariat “in itself” becomes a proletariat “for itself” that recognizes its own contradicting situation and acts in a class-conscious manner . The abolition of the dialectical contradiction through the victory of the proletariat means that both sides of the contradiction disappear: “If the proletariat wins, it has by no means become the absolute side of society, for it only wins by abolishing itself and its opposite . Then both the proletariat and its conditional opposite, private property, have disappeared ”. In the communist revolution it happens that the dialectical "opposition and its unity disappear". Here the dialectical energy disappears, since the "basic contradiction" between capital and labor has been eliminated.

The world and human knowledge

Engels expanded Marxism in his late work into a general theory of principles and knowledge. He tried to fruitfully combine the modern individual sciences with a materialistic and dialectical worldview . Many of his theories later formed the foundations of dialectical materialism , a term first that of Lenin coined as "real philosophy of Marxism" and later under Stalin simplified, strikingly elaborated and state doctrine (diamat = Dia lektischer Mat was raised erialismus).

The matter

For Engels, the ultimate principle of reality is matter. It represents “the real unity of the world”. Engel's concept of matter is comparable to the understanding of “ materia prima ” in the philosophical tradition. It is described by him as "a pure thought creation and abstraction":

“We disregard the qualitative differences of things by summarizing them as physically existing under the term matter. Matter as such, in contrast to the specific, existing matter, is therefore nothing that exists sensually. "

The essential property of matter is its “movement”, which Engels means “change in general”.

Movement is thus - contrary to a mechanistic view of the world - not reducible to its simplest form, mechanical movement. The qualitative differentiations of the forms of movement are a real phenomenon; the higher forms of movement cannot simply be traced back to the lower.

The dialectic of nature

Engels extends the concept of dialectic, which Marx used mainly to describe historical processes, to a general principle. He assumes that “in nature the same dialectical laws of motion prevail in the tangle of innumerable changes that also dominate the apparent randomness of events in history; the same laws which, also forming the thread running through the history of the development of human thought, gradually come to the mind of thinking people ”.

Engels differentiates between an “objective dialectic” that dominates nature and a “subjective dialectic” of human thought. The laws of dialectics can be reduced to three:

-

"The Law of the Penetration of Opposites"

- For Engels, even the simplest movement of matter, the change of location, is contradicting itself: “The movement itself is a contradiction; Even simple mechanical locomotion can only take place when a body is in one and the same moment of time in one place and at the same time in another place, in one and the same place and not in it. "

- The contradictions become even clearer in the higher forms of movement of matter. So life consists in the fact that “a being is the same and yet different in every moment”; it is “a contradiction that is present in the things and processes themselves, and that is always set and resolved”.

- Similarly, social development occurs through the incessant emergence of contradictions.

-

"The law of converting quantity into quality and vice versa"

- The law of turning quantity into quality says that the increase or decrease of a thing in terms of its quantity at a certain point leads to its qualitative change. This can be expressed in such a way that "in nature [...] qualitative changes can only take place through quantitative addition or quantitative withdrawal of matter or movement (so-called energy)".

- Engels explains this using examples from the natural sciences. So changing the number of atoms in a molecule changes the chemical compound; a certain current strength causes a line to glow; certain temperatures cause the transition of a body to another physical state .

- Engels wants to set himself apart from purely mechanistic interpretations of the world by opposing quantitative and qualitative differences. For him, the differences in qualities are properties of things and not just of perception.

-

"The Law of the Negation of Negation"

- The law of negation of negation describes the development in contradictions in more detail. Every system has a natural tendency to produce a new system within itself that is the negation of it. To illustrate this, Engels cites examples from biology. In this way, the stalk of the barley is created through its negation, which in turn produces the grain, whereupon it dies and in turn negates itself.

Thought and reality

Engels interprets the nature of human knowledge and thinking in a classically materialistic way as "products of the human brain". The reality is against the thinking priority as the "forms of thought" nothing more than "forms of being, the outside world [group], and these forms thought can never of itself, but just draw from the outside world and derive".

With regard to the genesis of human knowledge, Engels basically takes an empirical position. For him, the starting point of human knowledge is experience . For him, even the mathematical terms are not a priori , but are borrowed from the "outside world":

"Like the term number, the term figure is borrowed exclusively from the outside world, not originating in the head from pure thinking. [...] Pure mathematics has as its object the spatial forms and quantity relationships of the real world, ie very real material."

Engels rejects the idea of an absolute limit of human knowledge and, in particular, the opposition between appearance and a fundamentally unknowable " thing in itself ". If we know all the properties of a thing and are able to analyze it down to its last elements, then we also know the thing in itself.

Contemporary controversies

Like Marx and Engels, Auguste Comte (1798–1857) represented a view of history that assumed the necessary stages of development . However, he rejected the Marxian notions of class struggles and revolutions with the goal of a just society and developed a worldview based on empiricism, contrary to dialectical and historical materialism. He coined the term positivism , which Marx dealt critically with.

The key concepts of the British liberal philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) were freedom and tolerance. On this basis he criticized the thinking of Karl Marx. Mill stood up for the freedom of the individual and, like Comte, rejected Marxist concepts of class and class struggle. As a supporter of representative democracy , albeit graded according to education, he turned against the revolutionary ideas of Marx and Engels. In writing his theory of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, Marx critically referred to Mill's economic notions of moderate capitalism without immense growth rates. As a representative of utilitarianism , Mill rejected Marxist historical optimism. Like Marx, Mill did not advocate unrestricted rule by the majority of the population. While the former postulated the revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat as a transition to a society of freedom for all people (communism), Mill wanted to legally protect the freedom of every person as much as possible.

reception

See also: History of Marxism

German labor movement and social democracy

The German labor movement was referring to 1870 partly on Marxism. At first there was a connection between Marxian views and the teachings of Ferdinand Lassalle . Following Friedrich Engels' Anti-Duhring "(1878), in which he elaborated Marx's theory academically, formed gradually concept of" Marxism "out and spread as a comprehensive ideology in the working class and in small parts of the educated middle class .

After the death of Engels (1895), Karl Kautsky (1854–1938) was regarded as the leading theoretician of Marxism in German social democracy . Kautsky understood the decline of capitalist society, described by Marx, as a quasi natural law process, at the end of which power would fall to the proletariat and its party of their own accord. Therefore, he did not consider revolutionary efforts necessary to achieve this goal. Eduard Bernstein (1850–1932) is considered to be the founder of Marxist revisionism . He wanted to replace the social revolution with a policy of social reform in which the state is given a decisive role through the introduction of universal and equal suffrage.

Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919) rejected Bernstein's conclusion that one could achieve a socialist order without a revolution, as reformism . She advocated the thesis of the necessary collapse of capitalism. The real revolutionary weapon of the proletariat is the spontaneous, unorganized mass strike, which creates the class consciousness necessary for the revolution . In addition to her rejection of any dictatorship, she formulated a clear commitment to freedom of expression with her well-known sentence: “Freedom is always the freedom of those who think differently”.

Soviet Marxism

Soviet Marxism goes back to Lenin's (1870–1924) interpretation and further development of Marxism. According to Lenin, the working class can only develop a “trade union” consciousness on its own. According to this, only the intellectuals are able to bring scientifically founded class consciousness into the proletariat. Lenin was convinced that the revolution in backward countries can only be successful if it is the initial spark of the world revolution ; H. the revolution leaps into the capitalist centers. He developed the theory that the bourgeois state apparatus must be smashed and a revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat - under the leadership of the Communist Party - must be established. In his polemical argument with Karl Kautsky, he emphasized the violence of this process and rejected the idea already advocated by Engels that socialism could also be established with parliamentary methods. Lenin distinguished between a lower and a higher phase of communism. In the latter, everyone would be able to independently manage social production, so that state guidance and control would no longer be necessary.

After Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin first established the term Leninism , later the term Marxism-Leninism, and in his work On Dialectical and Historical Materialism (1938) completed the solidification of Marxist philosophy into dogma . He developed the “world view of the Marxist-Leninist party” and set up the doctrine of “ building socialism in one country” because the world revolution expected by Marx, Engels and Lenin had not materialized. His reign of terror based on the Marxism he interpreted is known as Stalinism .

Austromarxism

The Austrian school of Austromarxism , which emerged in 1903 and existed until the 1930s, held on to historical materialism in contrast to revisionism, but emphasized the necessity of social revolution and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat with the principle of majority rule within the framework of parliamentary-democratic frameworks Connecting Institutions ( Third Way ). The common starting point of the Austromarxists - Otto Bauer (1881–1938), Max Adler (1837–1937), Friedrich Adler (1879–1960), Rudolf Hilferding (1877–1941), Karl Renner (1870–1950) - was the reception of the Marxist Theory on the background of the critical philosophy of Immanuel Kant .

Neo-Marxism

The neo-Marxism has emerged as a response to social democratic and communist Soviet interpretations after the First World War. The starting point was the accusation against Karl Kautsky that he was flattening revolutionary Marxism into an undialectical theory of evolution and criticizing the tendencies in Soviet communism to present Leninism as a binding version of Marxism. The focus of interest was a reinterpretation, including the early writings, the work of Marx and the further development of his theory.

Germany

George Lukács (1885–1971) took the view in “ History and Class Consciousness ” (1923) that the historically necessary emergence of socialism was a dialectical movement of the “self-negation” of capitalism. The capitalist mode of production causes the relationships between people to appear as a relationship of things ("reification"); the goods become a "universal category" for society as a whole. In the proletariat, however, this process turns into revolutionary class consciousness, whereby the reifying structure of capitalism can be broken through in revolutionary action.

The philosophers of the Frankfurt School exerted a great influence on the philosophical discourse with the critical theory of society they developed : Max Horkheimer (1895–1973), Theodor W. Adorno (1903–1969), Erich Fromm (1900–1980), Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979). In their central work " Dialectic of Enlightenment " (1947), Horkheimer and Adorno present a Marxist-dialectical analysis of the contradictions after the Second World War. Shaped by the experiences of National Socialism and Stalinism , today's capitalist society is subject to technological and bureaucratic constraints. A characteristic of contemporary capitalism is the predominance of “ instrumental reason ”, of purely technical, purely rational thinking. Most of the representatives of the Frankfurt School transferred this criticism to the society of the USSR , which is why they rejected the theory and practice of Soviet Marxism.

Jürgen Habermas (1929) wants to continue the theory of the Frankfurt School in the sense of a critical theory of society. He is committed to the basic Marxist concern of progressive emancipation of man from the constraints of nature and society and attempts to work out the previously unexplained normative foundations of social processes on the basis of the social sciences .

Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957) tried to combine Marxism and psychoanalysis with one another in his work Dialectical Materialism and Psychoanalysis (1929). This direction, known as Freudo Marxism , became particularly popular in the 1968 movement .

The Critical Psychology , mainly from Klaus Holzenkamp developed (1927-1995), saw himself as a human science of Marxism and tied to the cultural-historical psychology Lev Semenovich Vygotsky (1896-1934) to.

Ernst Bloch (1885–1977) developed a philosophy of hope based on dialectical materialism - following on from Aristotle, Hegel and Judeo-Christian eschatology . As a reflection of what is “not yet conscious”, hopes relate to “not yet being”, to the possibilities for a better, more humane life that lie hidden in the world.

France

In France v. a. Henri Lefèbvre (1901–1991) and Roger Garaudy (1913–2012), through their criticism of party-official Marxism, broadened the discussion, which was also supported by phenomenology ( Maurice Merleau-Ponty , 1908–1961) and existentialism ( Jean-Paul Sartre , 1905 –1980) was influenced. Louis Althusser subjected Marx's texts to a structuralist analysis. In his theory of practice , Pierre Bourdieu explicitly refers to Marx among others.

Italy

The outstanding representative of neo-Marxism in Italy was Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937). For him, Marxism is a "philosophy of practice". Philosophy is “an expression of social contradictions”, but at the same time it brings about change; it is the "consciousness in which the philosopher [...] raises himself as an element to the principle of knowledge and thus of action". Gramsci's philosophy of practice aims to link “the general concepts of history, politics and economy in organic unity”.

Galvano della Volpe (1895–1968) and Cesare Luporini (1909–1993) examined v. a. the problem of the logical properties of a “materialistic dialectic” that demarcated it from the dialectic of Hegel.

Eastern Europe

In the neo-Marxist currents of Eastern Europe, the criticism of the Soviet Union's monopoly on interpretation and the plea for a different socialist practice were in the foreground. Important thinkers in Czechoslovakia are Karel Kosík (1926–2003), in Yugoslavia the practice group around the 1974/75 banned magazine “Praxis”, Gajo Petrovic (1927–1993), Mihailo Marković (1923–2010) and in Poland Leszek Kolakowski (1927–2009) may be mentioned.

The Budapest school around Ágnes Heller tries to develop the philosophical aspects of Marxism from a critical perspective to the "societies of the Soviet type".

Maoism

In China, Mao Zedong (1893–1976) developed his own theory of revolution, which for the underdeveloped societies of the Third World envisages the rural proletariat as the bearer of the proletarian revolution instead of the labor force that is usually lacking there. In contrast to Soviet-style Marxism-Leninism, Maoism assumes that after the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat in the unfolding socialist society, the class struggle will have to be intensified until not only the relations of production but also people's consciousness change in the communist sense be. In constant readiness for revolution, the popular masses should prevent the formation of new classes and class antagonisms under the leadership of the party. In his work “ On Contradiction ” he presents his interpretation of dialectical materialism.

Maoism exerted a great attraction on the communist parties and the liberation movements of the third world, but also on parts of the student movement of the 1960s and 1970s in the western industrialized countries.

Critical realism

Proponents of critical realism according to Roy Bhaskar (1944–2014) understand the work of Marx as a representation of the thoughts of critical realism, or they affirm the possibility of an interpretation of the work of Marx according to critical-realistic terms. They refer to ontological and epistemological as well as methodological approaches in Marx's work.

criticism

→ See also: Critique of Marxism

The basic philosophical assumptions of Marxism in all their facets have repeatedly come under strong criticism.

Scientific claim

Eric Voegelin (1901–1985) described Marxism practiced in the Soviet Union and National Socialism as political religions in 1938 .

The most important epistemological criticism was submitted by the Austro-British philosopher Karl Popper (1902–1994). He characterized Marxism as a pseudoscience . To distinguish between scientific and pseudoscientific theories, Popper introduced the criterion of the built-in immunization mechanism . Accordingly, Marxism was initially a thoroughly scientific theory, but was provided with such built-in mechanisms after its predictions about the necessary course of history clashed with the facts.

The French existentialist philosopher Albert Camus (1913–1960) also denied the scientific claim of Marxism in his work Der Mensch in der Revolte (L'Homme Révolté) , published in 1951 . He compared Marxism and Christianity and spoke of the former ironically as "scientific messianism". Communism means the end of history , a concept that is represented in Christianity by the expectation of salvation . Revolutions, which in practice turn away from their concepts of equality and justice and lead to oppression or even terror, he contrasted the idea of the revolt of the individual together with others. He accused Marxism of a monistic worldview that relates one-sidedly to economic conditions.

The Polish monk, philosopher and logician Joseph Maria Bocheński (1902–1995) also turned against the Marxist claim to science. Marxism is "a kind of belief" because it is "not based on experience", "but on the texts of the so-called classics". He does not use the methods of science, but "his own speculative" and is not freely debatable, rather he is viewed by his followers as an "unchangeable dogma".

Rupert Lay (born 1929) adds that Marxism generally counts philosophical theories as part of the superstructure , making Marxist theory invulnerable from outside. Arguing from a non-Marxist perspective is fundamentally impossible because the critic draws his ideas from the bourgeois world of thought, which is nothing more than a reflection of the capitalist base . Marxist theory thus goes into a self-contradiction: Marx and Engels themselves developed a system of thought from a capitalist basis that is supposed to overcome this very basis.

Criticism of religion

The Marxian criticism of religion is countered from a Christian perspective that it only refers to "distorted forms" of religion. Marx is therefore a prisoner of his own restrictive concept of ideology and has overlooked the utopian moments of Christianity. In addition, he presupposes a very limited image of God; he lacks “the characteristics that are precisely the decisive factors for the Christian understanding of God: selfless devotion, sacrifice, love; the characteristics that are typical of a pre-Christian image of God emerge: self-possession, sovereignty and rule ”.

Image of man

Against the Marxist image of man, it is argued that Marxism is ultimately not based on humanistic conceptions, since it does not regard human beings as “individual beings” but as “human species”. He advocates the “future humanity”, but neglects the “only real”, the “today's individual”. The individual thus becomes a mere “tool” and “means” of an unattainable vision. The central themes of suffering and death would be ignored; the death of the individual would ultimately be justified with the advancement of the species.

Furthermore, Marxism is accused of playing down evil . Marx does not take note of the "will to submit to other people [...] and thus the basic will to do evil". Likewise, he ignores the "reality of guilt ".

Economy

Karl Popper describes Marx's theory of value as an " essentialist or metaphysical theory". The idea that “there is something behind prices, an objective or real, or true value, to which prices relate only like 'manifestations'” shows the “influence of Platonic idealism with its distinction between a hidden essential and true value Reality and an accidental or deceptive appearance ”. The “labor theory of value” is “a completely superfluous part of the Marxist theory of exploitation”. "The laws of supply and demand" are sufficient to explain the value of a commodity. It is this mechanism which “under the condition of free competition, has the tendency to enforce the law of value”.

Philosophy of history

Lay raises the objection to the Marxist philosophy of history that the existence of objective historical laws is almost unanimously disputed by modern philosophy of science. He describes historical materialism as "crass economism" because he tries to explain historical processes monistically for just one reason. Marx and Engels accordingly underestimate the ability of the individual to largely detach himself from the prevailing ideology and to influence the shaping of history.

According to Popper, history cannot be viewed purposefully (towards communism) as a “history of class struggles” in ever higher social formations ( slave-holding society , feudalism and capitalism); There are also significant disputes within the classes. Marx overlooks the central role of ideas in the social process. Popper also criticizes the fact that the role of the economy is overemphasized and that of politics is neglected. Politics is not powerless, however, according to Popper, the economy depends on political violence, which can and must be democratically controlled.

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) repeatedly dealt critically with the Marxian deterministic view of history. It rejects Marxist optimism about history and the struggle for future social systems and refers every new generation to its task of becoming politically active. She too rejects the one-sided emphasis on the economic and criticizes the deification of the human image. It puts Marxism in line with the other ideologies of the 19th century, but emphasizes that often the best of a generation would have temporarily advocated this worldview.

The concept of communism as the goal of human history is described by critics as utopia , the entire worldview as ideology . All attempts to achieve this have so far come to an inhumane end. That communism will eliminate the central human contradictions is an unproven claim. It presupposes a person who cannot exist and is therefore an abstract theory. In their view, forms of common property versus private property contradict human nature; Expropriations have always led to the asocial neglect of common property, since the individual is more committed to his property than to the common goods.

Lay also criticizes the Marxist idea of the role of the proletariat. This had never been a carrier of revolutionary ideas: "The developers of a usable revolutionary strategy were always not system-integrated intellectuals (such as Marx himself)".

Dialectical materialism

Popper condemned dialectical and historical materialism as the basis for a “closed society” (dictatorship) in which the leadership circles believe they are in possession of the absolute truth and seem to find out objectively and scientifically about the alleged needs of their subordinates. Popper sees the Marxists as enemies of the “open society” (democracy).

Lay complains about dialectical materialism that he tries to subsume the complex reality under a few ontological and epistemological rules. For example, Engels' thesis that the senses “reflect” the world should be rejected. Rather, modern physics assumes that our "cognitive process modifies the object of cognition, even justifies certain properties, while we cannot recognize others directly [...]".

The existence of “non-material objects” can no longer be denied today. For example, the term “information” denotes something fundamentally “non-material”. These “non-material qualities” could not be traced back to matter (in the physical sense), “because they basically obey other laws that are not preformed in matter”. At least such a potential talent of the matter could not be proven, so that it was a pure “belief”. The way out, later taken by Lenin, to expand the concept of matter in such a way that it ultimately includes “everything” and thus takes the place of the traditional concept of “ being ”, is “extremely misleading, since by far most people do something with“ matter ” denote that is scientifically treated by physics, chemistry ”.

See also

literature

Primary literature

Karl Marx

- Booklets on Epicurean, Stoic and Skeptical Philosophy. 1839

- Difference between the democratic and epicurean natural philosophy. 1841

- On the criticism of Hegel's philosophy of law . 1843

- On the criticism of Hegel's philosophy of law. Introduction. 1844

- On the Jewish question . 1844

- Economic-philosophical manuscripts . 1844

- Theses on Feuerbach . 1845

- Letter to Annenkow. 1846

- The misery of philosophy . 1847

- Wage labor and capital . 1849

- The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte . 1852

- The future results of British rule in India. 1853

- Forms that precede capitalist production. 1858

- Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy . 1858

- Theories about added value . 1863

- The capital . 1867

- The civil war in France . 1871

- Criticism of the Gothaer program . 1875

- Marginal glosses on Adolph Wagner's "Textbook of Political Economy". 1880

Friedrich Engels

- Mr. Eugen Dühring's upheaval in science . 1878

- The development of socialism from utopia to science . 1880

- Dialectics of nature . 1883

- The origin of the family, private property and the state . 1884

Marx and Engels

- The holy family . 1844

- The German ideology . 1846

- Communist Party Manifesto . 1848

CD-ROM edition

- Mathias Bertram (ed.): Marx, Engels: Selected works. Directmedia Publishing, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-932544-15-3 (More than 100 writings by Marx and Engels can be found on a CD in digital form, the search function in particular is a useful aid. It is possible to quote from the MEW .)

- Review by Michael Berger on H-Soz-u-Kult , September 17, 1999 (with screenshot and listing of the fonts included)

Secondary literature

Introductory literature