Palatine dialects

| Palatinate ( Palatine ) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Rhineland-Palatinate , Baden-Württemberg , Hesse , Saarland , France , as emigrant dialects: USA , Canada , Banat | |

| speaker | about 1 million (estimated) | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

according to |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

plant |

|

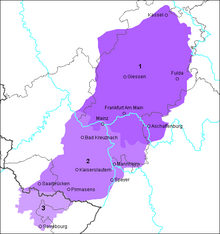

Pfälzisch (pfälzisch Pälzisch ) is a collective term for the dialects of the two rhein Frankish dialect groups Westpfälzisch and Ostpfälzisch ( Vorderpfälzisch ) which in turn are composed of individual dialects. Palatinate belongs to the West Central German , Franconian dialect area.

Linguistic geography

Palatinate can be distinguished from the neighboring dialects by means of the following isoglosses (see Rheinischer Fächer ):

- from the Moselle Franconian through the dat / das line ( Sankt Goarer line).

- from Hessian through the fescht / fest line

- from South Franconian and East Franconian through the appel / apfel line ( Speyerer line ) or the pund / pfund line ( Germersheimer line )

- from Lorraine through the hus / haus line

The transitions between the dialects are fluid, and there are also characteristic differences within the Palatinate, especially between the Front and West Palatinate. With these two dialect groups, however, you can draw a relatively clear dividing line along the borderline between the districts of Kaiserslautern and Bad Dürkheim . As with all dialects, each place has its own dialect tradition. There are certain sounds that can be found in one village, but no longer in the neighboring village.

The dialects of the former administrative district of the Palatinate in Rhineland-Palatinate primarily belong to the Palatinate language area . In addition, there is the Saarpfalz district bordering to the west - with the exception of some dialects in the southern part, which have Lorraine characteristics - and parts of the rest of the Saarland , the Electoral Palatinate in Baden-Württemberg ( Kurpfälzisch ), the extreme north of Alsace (southernmost town Selz (Alsace) ), parts of the Hunsrück bordering the Palatinate , the Bergstrasse region in Hesse and parts of the Odenwald and Rheinhessen . The Palatinate-speaking area thus extends beyond the borders of the Palatinate; on the other hand, the dialects spoken in the Palatinate, which lie southeast of the appel / apple line or the pund / pfund line ( Verbandsgemeinde Hagenbach ), are counted as southern Franconian.

In the vernacular, however, those dialects of the Palatinate that are spoken outside of the Palatinate i. d. Usually not referred to as Palatinate , but as Saarland, Rheinhessian etc.

The gebroch-gebroche-Linie divides the Palatinate into West Palatinate and East or Front Palatinate. In West Palatinate, the past participle has no ending in strong verbs (gebroch, Gesung, kumm), in Front Palatinate it ends in -e (g (e) broche, g (e) sunge, kumme) .

During the waves of emigration from Europe to North America , a particularly large number of people from the Palatinate emigrated from the middle of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century. They used the dialect they had brought with them for ten generations alongside English. In the US states of Pennsylvania , Ohio , Indiana and 29 other US states as well as in Ontario , Canada , the dialect of the old-order Mennonites and the Amish even remains the dominant language to this day. Hundreds of thousands of Americans and Canadians still speak this dialect, which is very similar to the recent Palatinate and which users themselves call "Deitsch". In English it is called Pennsylvania German, but it is usually incorrectly called Pennsylvania Dutch . Those emigrants whose means were insufficient to continue their journey settled on the Lower Rhine , which is why there are some Palatinate language islands there .

The linguistic geography of the Palatinate on the left bank of the Rhine is described in the Middle Rhine Language Atlas .

phonetics

In the Palatinate, as in all Central German dialects , the High German sound shift was not carried out completely; The initial p-sounds obtained are characteristic , as in the well-known saying: In de Palz, de Parre (r) and de Peif go into Ker (s) ch.

Further peculiarities of the Palatinate:

Consonants

- Tendency to voicing in plosives ; In and out loud: / t / → [d]; inside: / p; k / → [b; G]

- Old High German t initially becomes d, except in relatively young words borrowed from High German: Diir, Deer "Tür"; Rishdish "correct"; but: tea, terror, tuub "tube"

- Collapse of the phonemes / ç / (ch) and / ʃ / (sch) to [ ʃ ] (sch) (almost throughout the Pfalz) or [ ç ] (Saarpfalz)

- Special features of the pronunciation of intervocal d / t:

- Rhotazism (especially with older speakers and / or with increasing proximity to Saarpfalz ), for example guude → guure / guːrə /

- Lambdazismus : in parts of the Electoral Palatinate, the Northwest Palatinate and in isolated localities in the Saar and Front Palatinate ( e.g. Altrip ) for example Wedder → Weller

- Replacing d by a [ ð ] in individual places in the Vorderpfalz. This phenomenon has all but disappeared, the sound is being replaced by d, r, l or even j by the younger generation .

- In certain letter combinations, the d is completely

omitted

- terrible → researchable / fearable / terrible "terrible"

- you little (d) "you are"

- The combination gh is mostly pronounced like k , bh rarely like p

- ghowe "lifted" → kowe ( Des hab isch ghowe / kowe "I lifted that"), gherd "heard" → keerd ( Hoschd des ned kerd? "Didn't you hear that?"). In written texts, the gh- graphic is used to make the morphology visible and thus to make reading easier (ghowe, gheerd) .

- bhalde "keep" → palde ( des konnscht palde "you can keep that")

Vowels

- In Standard German , the Middle High German vowels / diphthongs ei [ ɛɪ̯ ] and î [ iː ] coincide to form the diphthong ei [ aɪ̯ ], while these are differentiated in Palatinate. The Middle High German ei corresponds in the Palatinate to ää (Kurpfälzisch aa / åå, Saarpfälzisch äi ): Schdää, Sääf, Klääd “stone, soap, dress”. The Middle High German î corresponds to ai / oi in Palatinate : Woi, doi, soi "Wein, dein, sein".

- It is the same with the Middle High German ou and û, which coincide with au in High German . The Middle High German ou finds its equivalent in the Palatinate aa (in the Southern Palatinate and parts of the Northwest Palatinate ää ): Aag, Schdaab, Raach "Auge, Staub, Rauch". The Middle High German û is pronounced as au as in High German : house "house".

- Elongation and opening up r, especially in the West Palatinate, for example, [ é ] → [ ɛː ] ([ ɛːɐ̯d ] "Earth"), [ ʊ ] → [ ɔ ] ([ dɔɐ̯ʃd ] "thirst ").

- Middle High German short u before nasals , which has often become o in High German , has been preserved in Palatinate as u : Sunn "sun" (mhd. Sunne ), cumme "to come". u also occurs in single words like vun “from” and borrowed from French like words like Unggel “ oncle ” (French oncle ).

- Slurring of -er in final to -a [ ɐ ] or [ a ] is common in much stronger shape than in the High German vernacular.

- Nasalization does not occur everywhere, but for example in the Upper Palatinate, for example Land → [ lɑ̃nd / lɔ̃nd ] (often written as Lånd ).

- In southern Palatinate there is sometimes diphthongization, for example grouß "tall", and ee for Middle High German ou, for example Free "woman" (elsewhere Fraa ).

In Palatine there are also no sounds ö, ü and eu / äu , they are rounded to e, i and ai . Examples:

- larger (Middle High German grœzer ) → greeßer

- Spoon (Middle High German spoon ) → Lewwel / Leffel

- Furniture (French meuble ) → Meebel / Meewel

- Hügel (Middle High German hill, hübel ) → Hischel / Hiechel / Hiwwel / Hewwel

- tired (Middle High German tired ) → miid

- Houses (Middle High German hiuser ) → Haiser

End sounds are also often omitted, but the plural can usually still be distinguished from the singular ( apocopes ):

- Dog, dogs → dog, Hunn (West Palatinate)

- Pan, pans → Pann / Pånn, Panne / Pånne

- Lamp, lamps → Låmb, Låmbe

- Monkey, monkey → monkey, monkey

Consonants between two vowels can also be omitted:

- have → hann (Westpfalz) / hawwe, hänn (Vorderpfalz)

- carry → draa (n) (West Palatinate) / draache, draae (Vorderpfalz)

grammar

Compared to Standard German (as with other dialects), the grammar is characterized by a strong reduction in the nominal and verbal system.

Verbal system

The Palatinate knows only four tenses: present tense, perfect and past perfect and the simple, d. H. composite future. The past tense has disappeared apart from a few remaining forms in the auxiliary verbs and is replaced by the perfect tense. There is only one future tense combined with the auxiliary verb “werre” (to be). A future is usually expressed by the present tense with the appropriate context. Without a time specification, the future is expressed by the said future tense. The past perfect is rare.

Conjugation of "to have":

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Conjugation example (weak verb "go" (to go), West Palatinate / Front Palatinate):

- Present:

| Present | |

| Singular | Plural |

|---|---|

| i (s) i go (n) | go to me |

| you go (d) | you go |

| he / she / it goes | they go |

| imperative | |

| go | go |

- Perfect: i (s) ch am gång (e) etc.

- Past perfect: i (s) ch war gång (e) etc.

- Future tense : i (s) ch werr go / go etc., present tense, if the time is given or it is evident from the context that the action cannot take place in the present. E.g .: I (s) ch go no (ch) Ameriga "I'm going to America"

As you can see, all three plural forms are the same in regular conjugation, not just the first and third person as in Standard German.

The participle is sometimes formed differently than in Standard German, e.g. B. gesass instead of "sitting" or gestock "stuck" instead, but intends instead of "thought," gewisst instead of "know".

The modes are missing the subjunctive, with the exception of the subjunctive II in some auxiliary and modal verbs:

- han / hawwe "have": he has / hott → he would have

- meaning "to be": she is → she would be

- dun / due “to do”: es dut → es deet

- know "know": he can → he knows

The auxiliary verb is modified for other verbs; if none is available, "dun" is switched on:

- He hot g (e) saacht, the hott net loud enough g (e) shouts. "He said she did not call loud enough." (Mostly in the Upper Palatinate)

- He has sown, she has called out loud enough. "He said she hadn't called loud enough." (Mostly in West Palatinate)

- He saacht that deet net loud enough to call. "He says she doesn't call loud enough." (Mostly in the Upper Palatinate)

- He sowed that deet does not call out loud enough or He sowed that it does not call loudly enough. "He says she doesn't call loud enough." (Mostly in West Palatinate)

Nominal system

A genitive is unknown; it is replaced by auxiliary constructions with the help of the dative. Example:

- High German: "Gertrud Schäfer's uncle is Harald Weber's colleague";

- West Palatinate: Em shepherd Gertrud is Unggel is'm Wewer Harald is Kolleech.

- Upper Palatinate: De Ungel vun de Gertrud Schäfer is Harald Wewer so in Kolleech or De Schäfers Gertrud ihrn Ungel is Wewers Harald soin Kolleech.

- Northern Palatinate: Em Schäfer Getrud soi Unggel is däm Weeber Harrald soi Kolleeg.

Relative clause

Instead of the relative pronouns “der, die, das” (in the sense of “which, which, which”), “wo” or wu is used in the Palatinate .

Example: Do you know who is running in front? "Do you know the one who is walking in front?"

Pronouns

The personal pronouns differ from standard German. The difference between stressed and unstressed pronouns (genitive omitted, West Palatinate) is important:

Emphasizes:

- "I": i (s) ch, me, mix

- "You": you, you, you

- "He / she / it": the, the, the, derre, the / the, the, the

- "We": me, us, us

- "You": you, eisch, ei (s) ch

- “They” die, denne, die

Unstressed:

- "I": i (s) ch, ma, misch

- "You": (d), there, you

- "He / she / it": a, (e) m, (e) n / se, re, se / s, (e) m, s

- "We": ma, us, us

- "You": (d) a, eisch, ei (s) ch

- "She": se, ne, se

Example of unstressed pronouns:

- when (de) meensch (t) "if you mean"

- when a meent "when he means"

- when a meenen "if you think so"

- when do you see meen "if you mean"

The "she" is alien to the Palatinate in a stressed position, both as a feminine 3rd person singular and as a 3rd person plural, and is replaced by the in this position . In the unstressed position, however, “she” reads se . Especially in West Palatinate, women are basically neutral, instead of "they" it is usually said .

- It Elfried called. "Elfriede called."

Article and grammatical gender

As is common in all of southern Germany, people are always named using the article, and surnames are generally put in front. For example, the High German sentence “Peter Meier goes to Müller” corresponds to De Meier in Palatinate Peder goes to / goes to Millers .

The Palatinate knows three genders (certain articles: de, die, es ). The indefinite article e [ə] is the same for all three genders in West Palatinate, in Front Palatine there are the articles en (masculine) and e / enni (feminine, unstressed / stressed). Females (with the exception of the Vorderpfälzischen) are mostly neuter and not feminine (as in Mosel-Franconian , in Ripuarian and in parts of Hessian )

Girls / women are:

- (in West Palatinate) neutral; originally always when the first name stands alone; in little girls and young women; if it is an acquaintance; when a relationship is expressed in terms of ownership (em Oddo seins) .

- feminine, if the person is indicated indirectly and gender or ending require it (the Müllersch, em Oddo is Freindin); if one has the feeling that the neutral form is not appropriate (the Elfriede); if it concerns a distant and / or prominent person, especially from the non-Palatinate-speaking area (then the foreign prefix of the first name is used: Uschi Glas instead of Glase Uschi )

Emancipation has not left its mark on the West Palatinate either. So one observes increasingly and especially in urban areas ( Kaiserslautern , Pirmasens ) the use of the female first name instead of it .

This requires a bit of tact, because the use of the without a first name has a derogatory appeal and is always used instead of it in the rich palette of insults in the West Palatinate . Consequently, the value-neutral foreign word is spreading increasingly to the use of language.

- es Uschi → the Uschi

- it has sown → she has sown

vocabulary

The vocabulary of the Palatinate is described in the Palatinate dictionary .

In vocabulary, numerous find (especially in the elderly population) loan words from French as the Lawor for basin (of lavoir ) which Bottschamber (of pot de chambre " chamber pot "), the Hussjee (of huissier " bailiff ") or the prompt particles Alloo, alla (from allons "we go forward, go, well then"). Some of the words of French origin were borrowed directly from the Lorraine dialects and therefore show a sound that is based on northeastern French, for example Mermidd, Mermedd "saucepan", which is based on Lorraine mermite and not on standard French marmite "cookware". Many more words, however, were borrowed from the standard French language between the 17th and 19th centuries, a time when the French language and culture had a strong position in the nobility and the educated classes of Germany. These were then also adopted by the common people in their dialects and are kept there as "sunken" words, while the German standard language has long since given them up again. Examples are Blimmoo "feather bed" (French plumeau ) or the Lawor and Bottschamber mentioned above . Also striking are the many French loanwords in administrative language such as Määr "mayor" (French maire ) or the aforementioned Hussjee, which were founded in the late 18th to the late 19th century when the Palatinate belonged to French law.

Some loan words from West Yiddish are also represented in Palatinate, from its Hebrew-Aramaic component, for example, Kazuff for butcher or Zores for quarrel, and from the Romance component ore “pray in the synagogue, learn in a low voice , moan, chat” (West Yiddish ore "Pray", from Latin orare ) or bemmsche " bellow poems" (West Yiddish bemsche "bless", from Latin benedicare ). These date from the time when numerous Jews lived in the Palatinate and its neighboring regions; Speyer, Worms and Mainz were important centers of Jewish learning in the Middle Ages.

Characteristic are the Palatinate idioms ah jo, high German "yes, of course" (example: ah jo, nadierlich tringge ma noch en schobbe ) and alla hopp, alla guud, high German "well then" (example: alla hopp, enner still works ) . Eifel people would be comparable idioms .

Palatine seal

There is a diverse range of Palatine poetry and prose poetry. Traditionally, this was mainly worn by folk “ homeland poets ”, many of whom enjoyed great popularity. Since the Palatinate lacks numerous elements that are indispensable for a written language, the results in retrospect are sometimes of an involuntarily humorous quality, especially when, in addition to the cumbersome use of the dialect, there is also a clichéd topic choice from the area of “ Weck, Worscht un Woi “is coming.

However, at the annual Bockenheim dialect poetry contest and the three other important competitions in Dannstadt , Gonbach and Wallhalben / Herschberg, it can be stated that the reform efforts in Palatinate dialect poetry have borne fruit. Modern dialect lyric poetry increasingly produces poems of a high literary level and partly avant-garde design. There are also approaches to modern dialect dramas, for example in the “scenic performance” section, which the Dannstadter Höhe dialect competition had included in the program for a few years from 2001.

In terms of the history of its origins, dialect literature is folk and homeland poetry with the main genres of poetry, Schwank and oral narration. The dialect, as a pure spoken language, also lacks the means to, for example, write more complex times in a satisfactory manner. There have been attempts to write long forms of prose, such as novels, in the Palatinate dialect, even if none of them have achieved any noteworthy popularity. Other long forms are also rare. Anthologies of contemplative and / or humorous content predominate.

Franz von Kobell (1803–1882), the old master of Palatinate dialect poetry, who was born in Munich and came from a Mannheim family of painters , expressed the problem of writing in dialect in a stanza about the “Pälzer Sprooch”:

- Who can sound a little bell?

- scream as it sounds.

- And who can write with the writing

- how beautiful blackbird sings?

- With all the effort no man can

- think not a bit more.

- Like with Glock and Vochelsang

- is it with de Pälzer Sprooch.

The best-known work of Palatinate dialect literature is probably Paul Münch's (1879–1951) “The Palatinate World History” (1909), formally somewhere between humorous poetry and verse epic. The self-ironic portrayal of the Palatinate as the crown of creation and the Palatinate as the center of the world has shaped the lion's share of all subsequent dialect poetry in terms of style and content to this day. Contemporary authors who also use the dialect as a means of expression for sophisticated literary texts include Arno Reinfrank (1934–2001), born in Mannheim , Michael Bauer , Albert H. Keil (both * 1947), Walter Landin (* 1952) and Bruno Hain (* 1954). You have u. a. tries to make the time of National Socialism understandable through Palatine texts and to connect it, for example, with the laying of stumbling blocks . The bosener group , named after the place where it was founded and where it was assembled , Bosen in the northeastern Saarland, has set itself the goal of promoting dialect literature from the Rhine and Moselle Franconian language areas.

Language examples

The Lord's Prayer

South Palatinate (exemplary):

- Our Vadder in heaven / Dei (n) name sell holy be, / Dei Kenichs rule sell kumme, / Dei (n) will sell gschehe / uf de earth just as in heaven. / Give us the bread, what we need there, / and forgive us our guilt / just as I deny where we are guilty. / And don't tempt us, / save us awwer vum Beese. / You gheert jo dominion / un the power / un the glory / up to alli Ewichkeit. / Amen.

West Palatinate (exemplary):

- Our Babbe in heaven / Dei Nåme should holy meaning, / Your kingdom should come, / What you want should be baser / on the earth as in heaven. / Give us bread, whatever we need, / and forgive us our guilt / just as we do where we are injustice. * / We do not tempt us, / but * all us vum Beese. / Because the jo has given it rich / un the strength / un the Herrlichkäät / until in alli Ewichkäät. / Amen.

West Palatinate ( Zweibrücken ) and, similarly sounding, Saar Palatinate ( Homburg and the surrounding area):

- Our Vadder owwe in heaven / Heilichd should make sense of the name / Dei kingdom should come / What de willsch, should basere / In heaven just like uff de earth / Give us heid ess bread, where mer de Daa iwwer need / Unn ve (r) Give us our guilt, / How sadly our guilty assured us. / We nedd in search / sunlit * eres us vum Beese / Because deer jo it is rich / and the power / and the Herrlichkääd / bit in all Ewichkääd / Ame

Upper Palatinate (exemplary):

- Unsa Vadda in heaven / Doi (n) Nåme shall hailisch soi, / Doi Raisch shall kumme, / Des wu you willschd, shall bassiere / as in heaven, so aa uff de Erd / Unsa däglisch Brood give us haid, un vagebb us unsa Guilt / eweso like ma denne vagewwe, wu on us worre sin. / Un duh us ned in Vasuchung, / sondan ealees us vum Beese. / Wail dia s'Reisch g (e) heead / un die Grafd / un die Healischkaid / in Ewischkaid. / Aamen.

It should be noted that "name" is not a genuine Palatine word and therefore, for once, the final syllable is not abraded. “Done” has no direct realization in the Upper Palatinate and West Palatinate, which is why it is translated as “happen”. The same applies to the word “guilty” in West Palatinate, which is why it has been replaced by the phrase mentioned above. “But” is very unusual in the colloquial Palatinate, mostly the expression is translated as “but” (awwer) .

literature

- Palatinate dictionary . Founded by Ernst Christmann, continued by Julius Krämer and Rudolf Post. 6 volumes and 1 booklet. Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden / Stuttgart 1965–1998, ISBN 3-515-02928-1 (standard work; given the price of over 1000 €, the work is mainly viewed in the reading rooms of larger Palatinate libraries and German university libraries; woerterbuchnetz.de ).

- Rudolf Post : Palatinate. Introduction to a language landscape . 2nd, updated and expanded edition. Pfälzische Verlagsanstalt, Landau / Pfalz 1992, ISBN 3-87629-183-6 .

- Rudolf Post: Small Palatinate Dictionary . Inkfaß edition, Neckarsteinach 2000, ISBN 3-937467-05-X .

- WAI Green: The Dialects of the Palatinate (Das Pfälzische). In: Charles V. J. Russ: The Dialects of Modern German. A Linguistic Survey. Routledge, London 1990, ISBN 0-415-00308-3 , pp. 341-264.

- Michael Konrad: Saach blooß. Secrets of the Palatinate . Rheinpfalz Verlag, Ludwigshafen 2006, ISBN 3-937752-02-1 .

- Michael Konrad: Saach blooß 2. Even more secrets of the Palatinate . Rheinpfalz Verlag, Ludwigshafen 2007, ISBN 978-3-937752-03-7 .

- Michael Konrad: Saach blooß 3. New secrets of the Palatinate . Rheinpfalz Verlag, Ludwigshafen 2009, ISBN 978-3-937752-09-9 .

- Michael Konrad: Saach blooß 4. Latest secrets of the Palatinate . Rheinpfalz Verlag, Ludwigshafen 2012, ISBN 978-3-937752-20-4 .

- Michael Landgraf : Pälzisch (Palatinate). Introduction and basic course for locals and foreigners . Agiro, Neustadt 2014, ISBN 978-3-939233-30-5 .

- Georg Drenda: Word atlas for Rheinhessen, Pfalz and Saarpfalz . Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert 2014, ISBN 978-3-86110-546-6 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Rudolf Post : Palatinate. Introduction to a language landscape. 2nd, updated and expanded edition. Pfälzische Verlagsanstalt, Landau / Pfalz 1992, ISBN 3-87629-183-6 , p. 20 summarizes the Front Palatinate and the Short Palatinate under East Palatinate .

- ^ Rudolf Post: Palatinate. Introduction to a language landscape. 2nd, updated and expanded edition. Pfälzische Verlagsanstalt, Landau / Pfalz 1992, pp. 180–193.

- ^ Rudolf Post: Palatinate. Introduction to a language landscape. 2nd, updated and expanded edition. Pfälzische Verlagsanstalt, Landau / Pfalz 1992, pp. 193-218.

- ↑ On the history of the dialect competition "Dannstadter Höhe". mundart-dannstadter-hoehe.de, accessed on April 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Culture against right-wing violence. verlag-pfalzmundart.de, accessed on April 17, 2017 .

- ^ Bosen Manifesto. bosenergruppe.saar.de, accessed on April 17, 2017 .