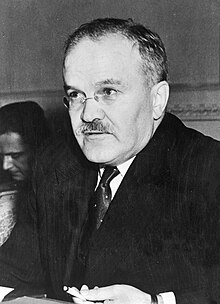

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov ( Russian Вячеслав Михайлович Молотов , scientific. Transliteration Vjačeslav Michajlovič Molotov ; actually Scriabin , Russian Скрябин ; born February 25 . Jul / 9. March 1890 greg. In Kukarka , Vyatka Governorate , Russian Empire (now Sovetsk, Kirov Oblast , Russia ); † November 8, 1986 in Moscow ) was a leading politician in the USSR and one of Joseph Stalin's closest confidants .

Molotov was Soviet head of government from 1930 to 1941 ( Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars ) and from 1939 to 1949 and 1953-1956 Soviet Foreign Minister (until 1946: People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs ).

Life and politics

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Scriabin was born in the small town of Kukarka near Vyatka (now Kirov ) in eastern Central Russia in 1890 as the son of a manager. According to a statement that occasionally appears in the secondary literature, but is not clearly substantiated, he is said to have been a nephew of the well-known composer Alexander Scriabin , but this is now considered refuted.

Ascent

He had been a member of the Bolsheviks in the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party since 1906 - at the age of 16 . Like many communists, he adopted a code name for his illegal work in imperial Russia; in his case it was Molotov , derived from molot ( Eng . hammer).

He was arrested for the first time in 1909 and had to spend two years in a Siberian camp. From 1911 he studied at the Polytechnic Institute in Saint Petersburg . He wrote for the illegal Pravda , the communist party newspaper of the Bolsheviks; Josef Stalin was a senior editor of this newspaper at the time. In 1913 Molotov was arrested again and deported to Irkutsk in Siberia. In 1915 he managed to escape, after which he returned to the capital, Petrograd . Here he became a member of the city's party committee.

1917, year of the revolutions

When the tsarist rule in Russia was ended with the February Revolution of 1917 , only a few Bolsheviks were free and active in Petrograd . Molotov headed Pravda these days. The Bolsheviks had only about 20,000 members in Russia who worked under the direction of a small office of the Central Committee in Petrograd and were led by workers Shjapnikov and Saluzki and the student Molotov. Molotov issued a manifesto calling for the creation of a provisional revolutionary government.

In March 1917, the released prisoners Lev Kamenev , Josef Stalin and Matwei Muranov as well as Jakow Sverdlow took over the party leadership. The young Molotov submitted to these experienced revolutionary leaders. He was again editor of the party newspaper Pravda, now headed by Kamenev and Stalin, and gradually became Stalin's closest collaborator.

Stalin and Kamenev revised Molotov's line in Pravda of an immediate seizure of power by the Soviets and the Bolsheviks. Only with the return of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin did he implement the line of immediate seizure of power through a revolution in the newly established Politburo . Molotov wrote:

"With Lenin's arrival in Russia, our party felt solid ground under its feet ... Before that moment, the party groped for its way, feeble and indecisive ... The party lacked clarity and determination."

Molotov now became a member of the Petrograd Soviet . Under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, he - who was not yet a member of the Politburo - took an active part in the preparation of the October Revolution .

From 1920 to 1921 he was the successor of Stanislaw Kossior First Secretary (Chairman) of the Communist Party of Ukraine .

At the center of power

At the Xth Party Congress of the Communist Party of Russia (Bolsheviks) in 1921, Trotsky supporters (including Krestinsky ) lost their offices as party secretaries, and Stalin supporters Molotov, Yaroslavsky and Michailov became secretaries from March 16, 1921 to March 27, 1922 of the Secretariat of the Central Committee (ZK) of the party. Molotov was called the "responsible secretary" at this time. The Secretariat of the Central Committee and the party's organizational office were run by Politburo member Stalin as “First Secretary” from 1921 and as General Secretary from April 1922. From 1921 to December 21, 1930 Molotov remained secretary of the Central Committee.

On January 1, 1926, with Stalin's help, he was promoted to the highest political body in the Soviet Union - he became a full member of the Politburo and remained so until June 29, 1957. He was thus able to stay in this center of power for 31 years.

Stalin's rise

In 1926 the Politburo consisted of the full members Josef Stalin, Lev Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev , Nikolai Bukharin , Michail Tomski and Alexei Rykov . At the 14th Party Congress, Stalin succeeded in expanding the Politburo in his favor by adding his followers Molotov, Mikhail Kalinin and Kliment Voroshilov . Through various coalitions in the Politburo, Zinoviev and Trotsky (ie the “left”), then Bukharin, Tomsky and Rykov (ie the “right”) in 1929 and 1930 (ie the “right”) were removed from the party's power centers by the Stalinists. They all eventually lost their lives between 1938 and 1940.

As a close confidante of Stalin, he turned out to be one of the leading drivers of deculacization in the early 1930s and in the 1930s under Stalin belonged to the most powerful ruling circle of the Soviet Union, which included Kirov († 1934), Voroshilov, Grigory Ordzhonikidze († 1937 ), Lasar Kaganowitsch , Valerian Kuibyshev († 1935) as well as Kalinin can be counted. During this time, Molotov was the undisputed number two in the Soviet hierarchy after Stalin. The German delegation, which negotiated the non-aggression pact in 1939, reports: "Only Molotov spoke to his boss (Stalin) as if he were among his own kind."

The outwardly correct Molotov was not only absolutely devoted to Stalin, but also a cold-blooded enforcer, who advocated the mass executions of the time of the Stalinist purges and the Moscow trials . For example, the minutes of the Politburo meeting of March 5, 1940, which contain the decision to shoot the Polish officers in the Katyn massacre , also have his signature.

Government work

In the background: Ribbentrop and Stalin

From December 19, 1930 to May 7, 1941 he was Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (Prime Minister). In this office he replaced the outlawed Rykov. After 1941 Stalin took over this office himself, which he held until his death. Molotov was 1941–1946 and 1953–1957 First Deputy Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (from 1946 Council of Ministers). He was jointly responsible for the forced collectivization of agriculture from 1928 to 1933, the political purges from 1936 to 1939 and the Moscow trials from 1938 to 1940.

After the Munich Agreement between Great Britain , France , Italy and the German Empire on the partition of Czechoslovakia in 1939, the USSR, which felt threatened, looked for a partner. In order to signal a change in the Soviet Union's foreign policy to Germany, Prime Minister Molotov also took over the office of Foreign Minister (People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs) and replaced Maxim Litvinov , who was of Jewish descent. Molotov remained Foreign Minister until 1949 and, after Andrei Wyschinski, held this office again from 1953 to 1956. The negotiations with France and Great Britain did not lead to a conclusion. Thus - surprisingly for the world public - in the presence of Stalin in Moscow on August 24, 1939, the German-Soviet non-aggression pact (Hitler-Stalin Pact) negotiated by Molotov and the German Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop was signed. Eight days later, Germany began with the invasion of Poland, the Second World War .

Second World War

On 27./28. In September 1939, Molotov and von Ribbentrop negotiated a "border and friendship treaty" between the Soviet Union and Germany in addition to the non-aggression pact in Moscow . This was followed by top-secret additions (e.g. about the annexation of the Baltic states ), the wording of which only became known 30 to 50 years later.

On November 12 and 13, 1940, Molotov was in Berlin and met von Ribbentrop and Hitler. The German side suggested that the Soviet Union join the Tripartite Pact , while Molotov demanded that Bulgaria be incorporated into the Soviet territory. The negotiations were fruitless. In addition, Molotov signed the neutrality pact with Japan in 1941 and participated in the important conferences of Tehran (1943), Yalta (1945) and Potsdam (1945).

In 1941, Stalin von Molotov took over the presidency of the Council of People's Commissars, which it had held since 1930. A few hours after the German attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Molotov described it in a radio address as an unprovoked act of aggression and declared that the Soviet Union would fight to victory. Stalin was - in recognition of his wrong political assessments - not ready at that time to make a statement to the Soviet people himself.

From October 19 to November 1, 1943, Molotov hosted the Moscow Conference in which Foreign Ministers Cordell Hull for the United States and Anthony Eden for Great Britain participated. The foreign ministers coordinated further cooperation, agreed the entry of the USSR into the war against Japan and laid the foundations of their European and world political cooperation after the end of the war.

In October 1944, Stalin and Churchill, as well as Foreign Ministers Molotov and Eden, met for another Moscow conference to discuss the future of the countries of Eastern and Southeastern Europe.

After the war

From 1945 to 1947 Molotov took part in all eight Foreign Ministers' Councils of the victorious states of World War II. Overall, he was characterized by an uncooperative attitude towards the Western powers.

Molotov's loss of power under Stalin

From the end of 1948, Stalin's distrust was directed against a number of Jewish intellectuals and political figures in the USSR who were persecuted as " rootless cosmopolitans ". When the then Israeli ambassador in Moscow and later Prime Minister Golda Meir visited the Moscow synagogue on Jewish New Year's Day, Molotov's Jewish wife Polina Shemchuschina is said to have been present. On November 7, 1948, the anniversary of the October Revolution, Molotov's wife Golda Meir met and asked the ambassador in Yiddish to continue to visit the synagogue. For Stalin, who flirted with anti-Semitic campaigns after 1945 because he assumed the Soviet Jews were loyal to Israel, the behavior of Molotov's wife was a grave affront. Stalin took this as an opportunity to dissolve the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the Soviet Union on November 20, 1948 and to intensify the anti-Semitic terror organized by Politburo member Malenkov and NKGB boss Viktor Abakumov . Polina was arrested, expelled from the party and banished to Kustanai in Central Asia for five years . According to some sources, Molotov soon thought she was dead.

Molotov did not take part in the vote on the conviction of his wife. A little later, however, he shows himself remorseful and distanced himself from Polina:

"'I express my deep regret that I did not prevent Shemchushina, a very loyal person to me, from making mistakes and establishing connections with anti-Soviet Jewish nationalists like Michoels ."

Because Molotov and his wife Polina greatly admired Stalin, not even Polina Stalin is said to have resented their exile - at least according to statements made by Stalin's daughter Svetlana. Polina died in Moscow in 1970.

The disgraced Molotov was dismissed as People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs on March 5, 1949. His successor was Andrei Wyschinski from 1949 to 1953 . At the same time, the People's Commissar for Trade Anastas Mikojan was dismissed for other reasons. But both remained members of the powerful Politburo as well as deputy chairmen of the Council of People's Commissars.

Molotov's relationship with Stalin continued to cool in the years after 1951. Nevertheless, the XIX. CPSU party congress opened by Molotov on October 5, 1952. Stalin, on the other hand, wanted to significantly rejuvenate the party leadership in 1952. He therefore criticized: “If we are talking about unity here, I cannot help but blame the inglorious behavior of some veteran politicians. I mean comrades Molotov and Mikoyan ... Molotov is loyal to our cause, but ... ", then he criticized Molotov, among other things, for his wife Polina and his - only alleged by Stalin - positive relationship with the Jews. In the new, considerably expanded 25-member presidium (later again Politburo) of the party, Molotov nevertheless received second place in the elections after Stalin, ahead of Malenkov, Voroshilov and Beria.

From August 1952, Molotov was no longer invited to the meetings of the Politburo. He and Mikoyan were in great danger, so that the latter later formulated: "Now it became apparent ... that Stalin wanted to break up with us, and that meant not only the political but also the physical annihilation." The inner circle of leaders included Stalin only Malenkov, Beria, Khrushchev and Bulganin. According to some reports, Molotov's death sentence was already formulated when Stalin fell ill. Nevertheless, an affected and grieving Molotov was on Stalin's deathbed from March 3rd to 5th, 1953.

After Stalin's death

After Stalin's death, Molotov was again in the inner circle of leadership of the party and the state with the following politicians: Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU, Malenkov as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Beria as Interior Minister , Molotov again as Foreign Minister and First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Voroshilov as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet , Bulganin as Defense Minister, Kaganovich as First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers and Mikoyan again as Minister of Commerce. Molotov supported Khrushchev when he ousted Beria in June 1953. The now ten-member party presidium also included Saburov and Pervuchin as ministers.

Molotov was foreign minister from 1953 to November 21, 1956. In this function he signed the Austrian State Treaty on May 15, 1955 in the Belvedere in Vienna . His successor after the XX. Khrushchev sponsored Central Committee Secretary Dmitri Shepilov became the party congress of the CPSU . From November 21, 1956 to July 4, 1957 he was Minister of State Control - an office that was subsequently replaced by a committee.

After the XX. At the CPSU party congress in 1956, a majority in the eleven-member Politburo, consisting of Malenkov, Molotov, Kaganovich, Saburov, Pervukhin, Bulganin and Voroshilov, unsuccessfully tried to overthrow Khrushchev as First Secretary in June 1957. They did not want to support the policy of drastic de-Stalinization . The Central Committee hastily convened by Khrushchev, who could rely on the loyalty of the army leadership, voted out Malenkov, Molotov, Kaganowitsch and Saburov and demoted Pervukhin. Molotov lost his leadership positions. From 1957 to 1960 he was only ambassador to the Mongolian People's Republic and from 1960 to 1962 he represented the USSR at the International Atomic Energy Agency . In 1962, Molotov was even expelled from the CPSU.

In December 1970, the 80-year-old Molotov justified the Great Terror in an interview in which he himself was a leading perpetrator:

"In 1937 it was necessary [...] Remnants of the enemies of various directions existed, and they could have united in the face of the impending fascist danger [...] We owe to 1937 that we did not have a fifth column during the war ."

Molotov also justified the extensive deportations of ethnic minorities , which the political leadership of the Soviet Union set in motion during the war years to punish allegedly hostile ethnic groups, a total of more than three million people:

“During the war, we learned of mass treason. Battalions of Caucasians stood against us at the front, they were in our rear. It was a matter of life and death, you couldn't be choosy. Of course, innocent people have also been affected. But I think that was done right back then. "

In 1984, two years before his death, he was rehabilitated under General Secretary Konstantin Tschernenko and re-admitted to the Communist Party.

Molotov was buried in a family burial site in Moscow's Novodevichy Cemetery .

Judgment on contemporaries

During the Winter War , the Finns named an improvised incendiary weapon after him - the Molotov cocktail .

Lenin nicknamed Molotov "Iron Ass".

Winston Churchill wrote in his book The Second World War in 1948 :

“Molotov has always stood in the midst of disaster and rubble all his life, whether it was that they threatened him or that he condemned others to do so. The Soviet machine had undoubtedly found a capable and in some respects characteristic representative in Molotov - he was always the loyal party member and the communist disciple ... As for his conduct of foreign policy, Mazarin , Talleyrand and Metternich would welcome him as one of theirs ... "

literature

-

Lars T. Lih , Oleg V. Khlevniuk and Oleg V. Naumov (eds.): Stalin's Letters to Molotov: 1925-1936. Yale University Press, 1995.

- German translation: Stalin. Letters to Molotov: 1925-1936. Siedler, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-88680-558-1 .

- Leon Trotsky : Stalin - A biography. Pawlak-Verlag and Kiepenheuer & Witsch.

- Felix Tschujew: Сто сорок бесед с Молотовым . Terra, Moscow 1991, ISBN 5-85255-042-6 .

- English translation: Felix Chuev: Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics. Published by Albert Resis. Ivan R. Dee, Chicago 1993, ISBN 1-56663-027-4 .

- Simon Sebag Montefiore : Stalin - At the court of the red tsar. S. Fischer-Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-10-050607-3 .

- Michel Tatu: Power and Powerlessness in the Kremlin. Ullstein, Frankfurt, 1967.

- Merle Fainsod : How Russia is governed. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1965.

Web links

- Literature by and about Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Vyacheslav M. Molotov. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Grave site in the Novodevichy Cemetery

- Heiner Wember : March 9th, 1890 - birthday of WM Molotow WDR ZeitZeichen on March 9th, 2020 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ↑ z. B. Friedrich Saathen: Of heralds and heretics. Biographical studies on the music of the 20th century. Böhlau, Vienna 1986, ISBN 3-205-05014-2 .

- ↑ Simon Sebag Montefiore : At the court of the red tsar . Frankfurt / Main 2006.

- ↑ latimes.com

- ↑ Leon Trotsky: Stalin. Pawlak and Kiepenheuer-Verlag, Cologne, ISBN 3-88199-074-7 , p. 294.

- ↑ Tomasz Mianowicz: The Soviet murders of Katyn , Charkow and Tver in April 1940. In Franz W. Seidler , Alfred de Zayas (Ed.): War crimes in Europe and the Middle East in the 20th century. Mittler, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-8132-0702-1 , p. 149.

- ↑ Timothy Snyder : Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin . CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62184-0 , p. 350.

- ↑ Quoted from Timothy Snyder: Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin . CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62184-0 , p. 354.

- ^ Molotov, Vyacheslav Mikhailovich . In: Carola Stern , Thilo Vogelsang et al. (Ed.): Dtv lexicon on history and politics in the 20th century . dtv, Munich 1974, vol. 2, p. 542.

- ^ Archie Brown: The Rise & Fall of Communism . 2009, p. 231.

- ↑ Barry McLoughlin: "Destruction of the Stranger": The "Great Terror" in the USSR 1937/38. New Russian publications . In: Hermann Weber , Ulrich Mählert (Ed.): Crimes in the name of the idea. Terror in Communism 1936–1938. Aufbau-Taschenbuch, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-7466-8152-8 , pp. 77–123 and pp. 303–312, here: p. 77 (first publication in the yearbook for historical communism research , 2001/2002, p. 50-88.)

- ↑ Jörg Baberowski : The red terror. The history of Stalinism. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-421-05486-X , p. 237 f.

- ↑ Winston S. Churchill: The Second World War. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 2003, ISBN 978-3-596-16113-3 , p. 180.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

|

Alexei Rykov |

Soviet head of government 1930–1941 |

Joseph Stalin |

|

Maxim Litvinov Andrei Vyshinsky |

Soviet Foreign Minister 1939–1949 1953–1956 |

Andrei Vyshinsky Dmitri Shepilov |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Molotov, Vyacheslav Mikhailovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Вячеслав Михайлович Молотов (Russian); Scriabin, Vyacheslav Mikhailovich (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Soviet head of government and foreign minister |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 9, 1890 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kukarka |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 8, 1986 |

| Place of death | Moscow |