Hyksos: Difference between revisions

m →Hyksos in popular culture: inserted space |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Asiatic invaders of Egypt, established 15th dynasty}} |

|||

[[Image:Hyksos.jpg|thumb|280px|right|An image representing the Egyptian pharaoh [[Ahmose I]] defeating the Hyksos in battle.]] |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2022}} |

|||

The '''Hyksos''' ([[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] ''heqa khasewet'', "foreign rulers"; [[Greek language|Greek]] {{Polytonic |Ὑκσώς}}, {{Polytonic |Ὑξώς}}, [[Arabic language|Arabic:]] {{Polytonic |الملوك رعاة الغنم }}, {{Polytonic |shepherd kings}}) were an Asiatic people who invaded the eastern [[Nile Delta]], initiating the [[Second Intermediate Period]] of [[Ancient Egypt]]. They rose to power in the [[17th century BC]], (according to the traditional chronology) and ruled Lower and Middle Egypt for 108 years, forming the [[Fifteenth dynasty of Egypt|Fifteenth]] and possibly the [[Sixteenth dynasty of Egypt|Sixteenth Dynasties]] of [[Egypt]], (''c.'' 1648–1540 BC).<ref>[[Egyptian chronology]].</ref> This 108-year period follows the [[Turin Canon]], which gives the six kings of the Hyksos 15th Dynasty a total reign length of 108 years.<ref name = "Vender">[http://www.nemo.nu/ibisportal/0egyptintro/6egypt/index.htm Second Intermediate Period] (SIP) by Ottar Vendel.</ref> |

|||

{{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=270|caption_align=center |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction =horizontal |

|||

| header=Hyksos |

|||

| image1 = Painting of foreign delegation in the tomb of Khnumhotep II circa 1900 BCE (Detail mentioning "Abisha the Hyksos" in hieroglyphs).jpg |

|||

| caption1 = A man described as "Abisha the Hyksos"<br>('''<big><big>𓋾𓈎𓈉</big></big>''' ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣswt, ''Heqa-kasut'' for "Hyksos"), leading a group of ''[[Aamu]]''.<br>Tomb of [[Khnumhotep II]] (circa 1900 BC).{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=131}}{{sfn|Bard|2015|p=188}}<br>This is one of the earliest known uses of the term "Hyksos".{{sfn|Willems|2010|p=96}} |

|||

| footer= |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Egyptian Dynasty list}} |

|||

'''Hyksos''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|h|ɪ|k|s|ɒ|s}}; [[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] ''[[wikt:ḥqꜣ|ḥqꜣ(w)]]-[[wikt:ḫꜣst|ḫꜣswt]]'', [[Egyptological pronunciation]]: ''heqau khasut'',{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=174}} "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern [[Egyptology]], designates the kings of the [[Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt]]{{sfn|Bietak|2001|p=136}} (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC).{{efn|Approximate dates vary by source. Bietak gives c. 1640–1532 BC,{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=1}} Schneider gives c. 1639–1521 BC,{{sfn|Schneider|2006|p=196}} and Stiebing gives c. 1630–1530 BC.{{sfn|Stiebing|2009|p=197}}|name=|group=}} The seat of power of these kings was the city of [[Avaris]] in the [[Nile Delta]], from where they ruled over [[Lower Egypt]] and [[Middle Egypt]] up to [[Cusae]]. |

|||

In the ''Aegyptiaca'', a history of Egypt written by the Greco-Egyptian priest and historian [[Manetho]] in the 3rd century BC, the term Hyksos is used ethnically to designate people of probable West Semitic, [[Levant]]ine origin.{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=131}}{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=10}} While Manetho portrayed the Hyksos as invaders and oppressors, this interpretation is questioned in modern Egyptology.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=5}} Instead, Hyksos rule might have been preceded by groups of [[Canaan]]ite peoples who gradually settled in the Nile delta from the end of the [[Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt|Twelfth Dynasty]] onwards and who may have seceded from the crumbling and unstable Egyptian control at some point during the [[Thirteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Thirteenth Dynasty]].{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|pp=177–178}} |

|||

Traditionally, only the six Fifteenth Dynasty rulers are called ''Hyksos''. The Hyksos had [[Canaan]]ite names, as seen in those which contain the names of Semitic deities such as [[Anath]] or [[Ba'al]]. They introduced new tools of warfare into Egypt, most notably the [[composite bow]] and the horse-drawn [[chariot]]. |

|||

{{Hiero|Hyksos|<hiero>S38-N29-N25:X1*Z1</hiero>|align=right|era=nk}} |

|||

== Hyksos rule in Egypt== |

|||

[[Image:ScarabBearingNameOfApophis MuseumOfFineArtsBoston.png|thumb|150px|right|Scarab bearing the name of the Hyksos pharaoh Apophis, now at the [[Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]]]] |

|||

The Hyksos kingdom was centered in the eastern [[Nile Delta]] and [[Middle Egypt]] and was limited in size, never extending south into [[Upper Egypt]], which was under control by [[Thebes, Egypt|Theban]]-based rulers. Hyksos relations with the south seem to have been mainly of a commercial nature, although Theban princes appear to have recognized the Hyksos rulers and may possibly have provided them with [[tribute]] for a period. The Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty rulers established their capital and seat of government at [[Memphis, Egypt|Memphis]] and their summer residence at [[Avaris]]. |

|||

The Hyksos period marks the first in which Egypt was ruled by foreign rulers.{{sfn|Morenz|Popko|2010|p=104}} Many details of their rule, such as the true extent of their kingdom and even the names and order of their kings, remain uncertain. The Hyksos practiced many Levantine or Canaanite customs as well as many Egyptian customs.{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=182}} They have been credited with introducing several technological innovations to Egypt, such as the [[horse]] and [[chariot]], as well as the [[Khopesh|sickle sword]] and the [[composite bow]], a theory which is disputed.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=12}} |

|||

The known rulers for the Hyksos [[Fifteenth dynasty of Egypt|15th dynasty]] are: |

|||

The Hyksos did not control all of Egypt. Instead, they coexisted with the [[Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Sixteenth]] and [[Seventeenth Dynasty of Egypt|Seventeenth Dynasties]], which were based in [[Thebes, Egypt|Thebes]].{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=7}} Warfare between the Hyksos and the pharaohs of the late Seventeenth Dynasty eventually culminated in the defeat of the Hyksos by [[Ahmose I]], who founded the [[Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt]].{{sfn|Morenz|Popko|2010|pp=108–109}} In the following centuries, the Egyptians would portray the Hyksos as bloodthirsty and oppressive foreign rulers. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" width="60%" |

|||

==Name== |

|||

===Etymology=== |

|||

{{Infobox hieroglyphs |

|||

|title = Hyksos |

|||

|width = 230px |

|||

|name = {{center|<hiero>S38-N29:N25..S38-N29:N25:Z2</hiero>}} |

|||

|name transcription = ''ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣsw'' / ''ḥqꜣw-ḫꜣswt'',{{sfn|Flammini|2015|p=240}}{{sfn|Ben-Tor|2007|p=1}}<br>"heqau khasut"{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=174}}{{efn|Spelling of the hieroglyphs in sources describing the archaeological record of the historical Hyksos: first set of characters is the singular, as appearing in [[:File:Painting_of_foreign_delegation_in_the_tomb_of_Khnumhotep_II_circa_1900_BCE_(Detail_mentioning_"Abisha_the_Hyksos"_in_hieroglyphs).jpg|Abisha the Hyksos]] in the tomb of [[Khnumhotep II]], c.1900 BC.{{sfn|Kamrin|2009}} The second set is in the plural, as appears in the inscriptions of known Hyksos rulers [[Sakir-Har]], [[Semqen]], [[Khyan]] and [[Aperanat]].<ref>{{cite web |title=The Sakir-Har door jamb inscription (slide 12) |work=The Second Intermediate Period: The Hyksos |url=https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/historyofegyptone11/files/18876478.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190202021123/https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/historyofegyptone11/files/18876478.pdf |archive-date=2019-02-02 |url-status=live}}</ref>}}<br>'''"Hyksos"''' |

|||

|name explanation = ''Ruler(s) of the foreign countries''{{sfn|Flammini|2015|p=240}} |

|||

|Greek = Hyksos (Ὑκσώς)<br>Hykussos (Ὑκουσσώς){{sfn|Schneider|2008|p=305}} |

|||

|image1=Hyksos characters.jpg |

|||

|image1 description=Standard characters for "Hyksos" in the label for "[[:File:Painting_of_foreign_delegation_in_the_tomb_of_Khnumhotep_II_circa_1900_BCE_(Detail_mentioning_"Abisha_the_Hyksos"_in_hieroglyphs).jpg|Abisha the Hyksos]]" in the tomb of [[Khnumhotep II]], c. 1900 BC.{{sfn|Kamrin|2009|p=25}} The crook (<big>'''[[List of Egyptian hieroglyphs|𓋾]]'''</big>, ''ḥqꜣ'') means "ruler", the hill (<big>'''[[List of Egyptian hieroglyphs|𓈎]]'''</big>) is a phonetic complement q/ḳ to 𓋾 while <big>'''[[𓈉]]'''</big> stands for (foreign) "country", pronounced ''ḫꜣst'', ''plural ḫꜣswt''.<br>The sign [[List of Egyptian hieroglyphs|𓏥]] marks the plural.{{sfn|Kamrin|2009|p=25}} |

|||

|}} |

|||

The term "Hyksos" is derived, via the Greek {{lang|grc|Ὑκσώς|italics=yes}} ({{lang|grc|Hyksôs|italics=yes}}), from the Egyptian expression <big>'''𓋾𓈎[[𓈉]]'''</big> ({{lang|egy|ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣswt|italics=yes}} or {{lang|egy|ḥqꜣw-ḫꜣswt|italics=yes}}, "heqau khasut"), meaning "rulers [of] foreign lands".{{sfn|Flammini|2015|p=240}}{{sfn|Ben-Tor|2007|p=1}} The Greek form is likely a textual corruption of an earlier {{lang|grc|Ὑκουσσώς|italics=yes}} ({{lang|grc|Hykoussôs|italics=yes}}).{{sfn|Schneider|2008|p=305}} |

|||

The first century AD Jewish historian [[Josephus]] gives the name as meaning "shepherd kings" or "captive shepherds" in his ''[[Against Apion|Contra Apion]]'' (Against Apion), where he describes the Hyksos as Jews as they appeared in the Hellenistic Egyptian historian [[Manetho]].{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=9}}{{sfn|Loprieno|2003|p=144}} |

|||

<blockquote>This whole nation was styled Hycsos, that is, Shepherd-kings: for the first syllable Hyc, according to the sacred dialect, denotes a king, as is Sos a shepherd. But this according to the ordinary dialect, and of these is compounded Hycsos; but some say that these people were Arabians.<ref>Against Apion, Flavius Josephus, 14.</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Josephus's rendition may arise from a later Egyptian pronunciation of {{lang|egy|ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣswt|italics=yes}} as {{lang|egy|ḥqꜣ-[[Shasu|šꜣsw]]|italics=yes}}, which was then understood to mean "lord of shepherds."{{sfn|Morenz|Popko|2010|pp=103–104}} It is unclear if this translation was found in Manetho; an Armenian translation of an epitome of Manetho given by the late antique historian [[Eusebius]] gives the correct translation of "foreign kings".{{sfn|Verbrugghe|Wickersham|1996|p=99}} |

|||

===Use=== |

|||

"It is now commonly accepted in academic publications that the term {{lang|egy|Ḥqꜣ-Ḫꜣswt|italics=yes}} refers only to the individual foreign rulers of the late Second Intermediate Period,"{{sfn|Candelora|2018|p=53}} especially of the [[Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Fifteenth Dynasty]], rather than a people. However, it was used as an ethnic term by Josephus.{{efn|"Two separate misconceptions persist, both in the scholarship and more popular works, surrounding the word "Hyksos." The first is that this term is the name of a defined and relatively large population group (see below), when in fact it is only a royal title held exclusively by individual rulers. Any standalone use of the word "Hyksos" in the following article refers specifically to the foreign kings of the 15th Dynasty."{{sfn|Candelora|2018|pp=46–47}} "[Josephus] also misrepresents the Hyksos as a population group (ethnos) as opposed to a dynasty."{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=1}} "Flavius Josephus used the designation "Hyksos" incorrectly as a kind of ethnic term for people of foreign origin who seized power in Egypt for a certain period. In this sense, for the sake of convenience, it is also used in the title and section headings of the present article. One should never forget, however, that, strictly spoken, the "Hyksos" were only the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty, and of simultaneous minor dynasties, who took the title ḥqꜣw-ḫꜣswt."{{sfn|Bietak|2010|p=139}}}} Its use to refer to the population still persists in some academic papers.{{sfn|Candelora|2018|p=65}} |

|||

In Ancient Egypt, the term "Hyksos" ({{lang|egy|ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣswt|italics=yes}}) was also used to refer to various Nubian and especially Asiatic rulers both before and after the Fifteenth Dynasty.{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=174}}{{sfn|Candelora|2017|pp=208–209}}{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|pp=123–124}} It was used at least since the [[Sixth Dynasty of Egypt]] (c. 2345–2181 BC) to designate chieftains from the [[Syria (region)|Syro]]-[[Palestine (region)|Palestine]] area.{{sfn|Kamrin|2009|p=25}} One of its earliest recorded uses is found c. 1900 BC in the tomb of [[Khnumhotep II]] of the [[Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt|Twelfth Dynasty]] to label a [[nomad]] or [[Canaan]]ite ruler named "[[:File:Painting_of_foreign_delegation_in_the_tomb_of_Khnumhotep_II_circa_1900_BCE_(Detail_mentioning_"Abisha_the_Hyksos"_in_hieroglyphs).jpg|Abisha the Hyksos]]" |

|||

(using the standard <big>'''𓋾𓈎𓈉'''</big>, ''ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣswt'', "Heqa-kasut" for "Hyksos").{{sfn|Willems|2010|p=96}}{{sfn|Curry|2018}} |

|||

{{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=200|caption_align=center |

|||

| align = left |

|||

| direction =horizontal |

|||

| header=Scarabs of Hyksos kings |

|||

| image1 = Hyksos on the seal of king Semqen.jpg |

|||

| caption1 = "[[Semqen]] the Hyksos" |

|||

| image2 = Khyan the Hyksos (Hyksos highlighted).jpg |

|||

| caption2 = "[[Khyan]] the Hyksos" |

|||

| footer= Scarabs of Hyksos kings, with "Hyksos" highlighted.{{sfn|Candelora|2017|p=211}} |

|||

| footer_align = center |

|||

}} |

|||

Based on the use of the name in a Hyksos inscription of [[Sakir-Har]] from Avaris, the name was used by the Hyksos as a title for themselves.{{sfn|Candelora|2017|p=204}} However, [[Kim Ryholt]] argues that "Hyksos" was not an official title of the rulers of the Fifteenth Dynasty, and is never encountered together with [[Ancient Egyptian royal titulary|royal titulary]], only appearing as the title in the case of Sakir-Har. According to Ryholt, "Hyksos" was rather a generic term which is encountered separately from royal titulary, and in regnal lists after the end of the Fifteenth Dynasty itself.{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=123–125}} However, Vera Müller writes: "Considering that S-k-r-h-r is also mentioned with three names of the traditional Egyptian titulary (Horus name, Golden Falcon name and Two Ladies name) on the same monument, this argument is somehow strange."{{sfn|Müller|2018|p=211}} Danielle Candelora and Manfred Bietak also argue that the Hyksos used the title officially.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=1}}{{sfn|Candelora|2017|p=216}} All other texts in the Egyptian language do not call the Hyksos by this name, instead referring to them as Asiatics ([[:wikt:ꜥꜣm#Egyptian|ꜥꜣmw]]), with the possible exception of the [[Turin King List]] in a hypothetical reconstruction from a fragment.{{sfn|Candelora|2017|pp=206–208}} The title is not attested for the Hyksos king [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi]], possibly indicating an "increased adoption of Egyptian decorum".{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=2}} The names of Hyksos rulers in the Turin list are without the royal cartouche and have the [[Throw stick (hieroglyph)|throwstick]] "foreigners" determinative.{{sfn|Ryholt|2004}} |

|||

[[Scarab (artifact)|Scarabs]] also attest the use of this title for pharaohs usually assigned to the [[Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Fourteenth]] or Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt, who are sometimes called "'lesser' Hyksos."{{sfn|Müller|2018|p=211}} The Theban Seventeenth Dynasty of Egypt is also given the title in some versions of Manetho, a fact which Bietak attributes to textual corruption.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=2}} In the [[Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt]] and during the [[Ptolemaic Dynasty|Ptolemaic Period]], the term Hyksos was adopted as a personal title and epithet by several pharaohs or high Egyptian officials, including the Theban official [[Mentuemhat]], [[Philip III of Macedon]],{{sfn|Hölbl|2001|p=79}}{{sfn|Candelora|2017|p=209}} and [[Ptolemy XIII]].{{sfn|Candelora|2017|p=209}} It was also used on the tomb of Egyptian grand priest [[Petosiris]] at [[Tuna el-Gebel]] in 300 BC to designate the [[Achaemenid Empire|Persian]] ruler [[Artaxerxes III]], although it is unknown if Artaxerxes adopted this title for himself.{{sfn|Candelora|2017|p=209}} |

|||

==Origins== |

|||

===Ancient historians=== |

|||

[[File:Ring scarab - Pharaoh exhibit - Cleveland Museum of Art (cropped).jpg|thumb|Blue glazed steatite scarab in a gold mount, with the cartouche of Hyksos ruler [[Khyan]]: <hiero>N5:G39-<-x-i-i-A-n->-S34-I10:t:N17</hiero> - "Son of Ra, Khyan, living forever!"]] |

|||

In his epitome of Manetho, Josephus connected the Hyksos with the Jews,{{sfn|Assmann|2003|p=198}} but he also calls them Arabs.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=9}} In their own epitomes of Manetho, the [[Late antique]] historians [[Sextus Julius Africanus]] and [[Eusebius]] say that the Hyksos came from [[Phoenicia]].{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=9}} Until the excavation and discovery of [[Tell El-Dab'a]] (the site of the Hyksos capital [[Avaris]]) in 1966, historians relied on these accounts for the Hyksos period.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=10}}{{sfn|Flammini|2015|p=236}} |

|||

===Modern historians=== |

|||

Material finds at Tell El-Dab'a indicate that the Hyksos originated in the [[Levant]].{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=10}} The Hyksos' personal names indicate that they spoke a [[Western Semitic]] language and "may be called for convenience sake [[Canaanites]]."{{sfn|Bietak|2016|pp=267–268}} |

|||

[[File:Retjenu, tomb of Sobekhotep 18th Dynasty Thebes.jpg|thumb|left|upright=0.7|A ''[[Retjenu]]'', associated with the Hyksos in some Egyptian inscriptions.{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=128}}]] |

|||

[[Kamose]], the last king of the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty, refers to [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi]] as a "Chieftain of [[Retjenu]]" in a stela that implies a Levantine background for this Hyksos king.{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=128}} According to Anna-Latifa Mourad, the Egyptian application of the term {{lang|egy|ꜥꜣmw|italics=yes}} to the Hyksos could indicate a range of backgrounds, including newly arrived Levantines or people of mixed Levantine-Egyptian origin.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=216}} |

|||

Due to the work of Manfred Bietak, which found similarities in architecture, ceramics and burial practices, scholars currently favor a northern Levantine origin of the Hyksos.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=11}} Based particularly on temple architecture, Bietak argues for strong parallels between the religious practices of the Hyksos at Avaris with those of the area around [[Byblos]], [[Ugarit]], [[Alalakh]] and [[Tell Brak]], defining the "spiritual home" of the Hyksos as "in northernmost [[Syria (region)|Syria]] and northern [[Mesopotamia]]".{{sfn|Bietak|2019|p=61}} The connection of the Hyksos to Retjenu also suggests a northern Levantine origin: "Theoretically, it is feasible to deduce that the early Hyksos, as the later Apophis, were of elite ancestry from [[Retjenu|Rṯnw]], a toponym [...] cautiously linked with the Northern Levant and the northern region of the Southern Levant."{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=216}} |

|||

Earlier arguments that the Hyksos names might be [[Hurrian]] have been rejected,{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=6}} while early-twentieth-century proposals that the Hyksos were Indo-Europeans "fitted European dreams of Indo-European supremacy, now discredited."{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=166}} Some have suggested that Hyksos or a part of them was of [[Maryannu]] origins as evident by their use and introduction of chariots and horses into Egypt.{{sfn|Woudhuizen|2006|p=30}}{{sfn|Glassman|2017|p=479–480}} However, this theory has been too rejected by modern scholarship. |

|||

A study of dental traits by Nina Maaranen and Sonia Zakrzewski in 2021 on 90 people of Avaris indicated that individuals defined as locals and non-locals were not ancestrally different from one another. The results were said to be in line with the archaeological evidence, suggesting Avaris was an important hub in the Middle Bronze Age eastern Mediterranean trade network, welcoming people from beyond its borders.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Stantis |first1=Chris |last2=Maaranen |first2=Nina |date=2021-01-01 |title=The people of Avaris: Intra-regional biodistance analysis using dental non-metric traits |url=https://www.academia.edu/66925960 |journal=Bioarchaeology of the Near East}}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

|||

===Early contacts between Egypt and the Levant=== |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| perrow = 2 |

|||

| total_width = 450 |

|||

| caption_align = center |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| header = ''Procession of the Aamu'' |

|||

| image1 = Procession of the Aamu, Tomb of Khnumhotep II (composite).jpg |

|||

| image2 = Drawing of the procession of the Aamu group tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan.jpg |

|||

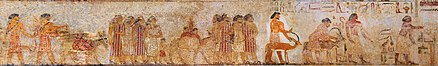

| footer = A group of West Asiatic foreigners, possibly [[Canaan]]ites, labelled as ''[[Aamu]]'' ({{lang|egy|ꜥꜣmw|italics=yes}}), including the leading man with a [[Nubian ibex]] labelled as ''Abisha the Hyksos'' ('''<big><big>𓋾𓈎𓈉</big></big>''' ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣsw, ''Heqa-kasut'' for "Hyksos"). Tomb of [[12th dynasty|12th-dynasty]] official [[Khnumhotep II]], at [[Beni Hasan]] (c. 1890 BC).{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=131}}{{sfn|Bard|2015|p=188}}{{sfn|Kamrin|2009|p=25}}{{sfn|Curry|2018}} |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| caption1 = |

|||

| caption2 = |

|||

}} |

|||

Historical records suggest that Semitic people and Egyptians had contacts at all periods of Egypt's history.{{sfn|Bright|2000|p=97}} The [[MacGregor plaque]], an early Egyptian tablet dating to 3000 BC records "The first occasion of striking the East", with the picture of Pharaoh [[Den (pharaoh)|Den]] smiting a Western Asiatic enemy.{{sfn|Russmann|James|2001|pp=67–68}} |

|||

During the reign of [[Senusret II]], c. 1890 BC, [[:File:Procession_of_the_Aamu,_Tomb_of_Khnumhotep_II_(composite).jpg|parties of Western Asiatic foreigners visiting the Pharaoh with gifts]] are recorded, as in the tomb paintings of [[12th dynasty|12th-dynasty]] official [[Khnumhotep II]]. These foreigners, possibly [[Canaan]]ites or [[nomads]], are labelled as ''[[Aamu]]'' ({{lang|egy|ꜥꜣmw|italics=yes}}), including the leading man with a [[Nubian ibex]] labelled as ''Abisha the Hyksos'' ('''𓋾𓈎𓈉''' ḥqꜣ-ḫꜣsw, ''Heqa-kasut'' for "Hyksos"), the first known instance of the name "Hyksos".{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=131}}{{sfn|Bard|2015|p=188}}{{sfn|Kamrin|2009|p=25}}{{sfn|Curry|2018}} |

|||

Soon after, the [[Sebek-khu Stele]], dated to the reign of [[Senusret III]] (reign: 1878–1839 BC), records the earliest known Egyptian military campaign in the Levant. The text reads "His Majesty proceeded northward to overthrow the Asiatics. His Majesty reached a foreign country of which the name was Sekmem (...) Then Sekmem fell, together with the wretched [[Retenu]]", where Sekmem (s-k-m-m) is thought to be [[Shechem]] and "Retenu" or "[[Retjenu]]" are associated with ancient [[Syria]].{{sfn|Pritchard|2016|p=230}}{{sfn|Steiner|Killebrew|2014|p=73}} |

|||

===Background and arrival in Egypt=== |

|||

The only ancient account of the whole Hyksos period is by the Hellenistic Egyptian historian [[Manetho]], who, however, exists only as quoted by others.{{sfn|Raspe|1998|p=126–128}} As recorded by Josephus, Manetho describes the beginning of Hyksos rule thusly: |

|||

<blockquote>A people of ignoble origin from the east, whose coming was unforeseen, had the audacity to invade the country, which they mastered by main force without difficulty or even battle. Having overpowered the chiefs, they then savagely burnt the cities, razed the temples of the gods to the ground, and treated the whole native population with the utmost cruelty, massacring some, and carrying off the wives and children of others into slavery (''Contra Apion'' I.75-77).{{sfn|Josephus|1926|p=196}}</blockquote> |

|||

[[File:Hyksos dagger handle.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35|[[Electrum]] dagger handle of a soldier of Hyksos pharaoh [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi]], illustrating the soldier hunting with a short bow and sword. Inscriptions: "The perfect god, the lord of the two lands, Nebkhepeshre [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi]]" and "Follower of his lord Nehemen", found at a burial at [[Saqqara]].{{sfn|O'Connor|2009|pp=116–117}} Now at the [[Luxor Museum]].{{sfn |Wilkinson |2013a |p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=wVbGDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT96 96]}}{{sfn |Daressy |1906 |pp=115–120}}]] |

|||

Manetho's invasion narrative is "nowadays rejected by most scholars."{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=5}} It is likely that he was influenced by more recent foreign invasions of Egypt.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=1}} Instead, it appears that the establishment of Hyksos rule was mostly peaceful and did not involve an invasion of an entirely foreign population.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=130}} Archaeology shows a continuous Asiatic presence at Avaris for over 150 years before the beginning of Hyksos rule,{{sfn|Bietak|2006|p=285}} with gradual Canaanite settlement beginning there {{circa|1800 BC}} during the [[Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt|Twelfth Dynasty]].{{sfn|Ben-Tor|2007|p=1}} Strontium isotope analysis of the inhabitants of Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period Avaris also dismissed the invasion model in favor of a migration one. Contrary to the model of a foreign invasion, the study didn't find more males moving into the region, but instead found a sex bias towards females, with a high proportion of 77% of females being non-locals.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Stantis|first1=Chris|last2=Kharobi|first2=Arwa|last3=Maaranen|first3=Nina|last4=Nowell|first4=Geoff M.|last5=Bietak|first5=Manfred|last6=Prell|first6=Silvia|last7=Schutkowski|first7=Holger|date=2020-07-15|title=Who were the Hyksos? Challenging traditional narratives using strontium isotope (87Sr/86Sr) analysis of human remains from ancient Egypt|journal=PLOS ONE|language=en|volume=15|issue=7|pages=e0235414|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0235414|issn=1932-6203|pmc=7363063|pmid=32667937|bibcode=2020PLoSO..1535414S |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Stantis|first1=Chris|last2=Kharobi|first2=Arwa|last3=Maaranen|first3=Nina|last4=Macpherson|first4=Colin|last5=Bietak|first5=Manfred|last6=Prell|first6=Silvia|last7=Schutkowski|first7=Holger|date=2021-06-01|title=Multi-isotopic study of diet and mobility in the northeastern Nile Delta|journal=Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences|language=en|volume=13|issue=6|pages=105|doi=10.1007/s12520-021-01344-x|s2cid=235271929 |issn=1866-9565|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

[[Manfred Bietak]] argues that Hyksos "should be understood within a repetitive pattern of the attraction of Egypt for western Asiatic population groups that came in search of a living in the country, especially the Delta, since prehistoric times."{{sfn|Bietak|2006|p=285}} He notes that Egypt had long depended on the Levant for expertise in areas of shipbuilding and seafaring, with possible depictions of Asiatic shipbuilders being found from reliefs from the [[Sixth Dynasty of Egypt|Sixth Dynasty]] ruler [[Sahure]]. The Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt is known to have had many Asiatic immigrants serving as soldiers, household or temple serfs, and various other jobs. [[Avaris]] in the Nile Delta attracted many Asiatic immigrants in its role as a hub of international trade and seafaring.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=4}} |

|||

The final powerful pharaoh of the Egyptian [[Thirteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Thirteenth Dynasty]] was [[Sobekhotep IV]], who died around 1725 BC, after which Egypt appears to have splintered into various kingdoms, including one based at Avaris ruled by the [[Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Fourteenth Dynasty]].{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|pp=177–178}} Based on their names, this dynasty was already primarily of West Asian origin.{{sfn|Bietak|2019|p=47}} After an event in which their palace was burned,{{sfn|Bietak|2019|p=47}} the Fourteenth Dynasty would be replaced by the Hyksos [[Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Fifteenth Dynasty]], which would establish "loose control over northern Egypt by intimidation or force,"{{sfn|Bietak|1999|p=377}} thus greatly expanding the area under Avaris's control.{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=180}} |

|||

[[Kim Ryholt]] argues that the Fifteenth Dynasty invaded and displaced the Fourteenth, however Alexander Ilin-Tomich argues that this is "not sufficiently substantiated."{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=6}} Bietak interprets a stela of [[Neferhotep III]] to indicate that Egypt was overrun by roving mercenaries around the time of the Hyksos ascension to power.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=5}} |

|||

===Kingdom=== |

|||

{{main|Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt}} |

|||

{{Location map+|Northern Egypt|caption=Key Sites of the Second Intermediate Period, in Northern Egypt. West Semitic in red; Egyptian in blue.{{citation needed|date=July 2020}}|relief=yes|width=300|places= |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label='''[[Avaris]]'''|position=top|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.787417 |lon_deg=31.821361|link=Avaris|label_size=80}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=[[Tjaru]]|position=left|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.8572 |lon_deg=32.3506|link=Tjaru|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=Tell el‑Yahudiyeh|position=left|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.4925 |lon_deg=31.554444|link=Tell el-Yahudiyeh|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=[[Heliopolis (ancient Egypt)|Heliopolis]]|position=left|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.129333 |lon_deg=31.307528|link=Heliopolis, Egypt|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=[[Tell Basta]]|position=left|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.57165881|lon_deg=31.51312613|link=[[Bubastis]]|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=Tell Farasha|position=left|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.68|lon_deg=31.72|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=[[Inshas]]|position=left|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.35|lon_deg=31.45|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=Tell el‑Maskhuta|position=right|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.551944 |lon_deg=32.098611|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=Tell er‑Retabeh|position=top|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.54828705 |lon_deg=31.96386495|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=Tell es‑Sahaba|position=bottom|mark=Red pog.svg|lat_deg=30.53 |lon_deg=32.06|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=[[Memphis (Egypt)|Memphis]]|position=left|mark=Blue pog.svg|lat_deg=29.85057823 |lon_deg=31.25253784|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=[[Lisht]]|position=left|mark=Blue pog.svg|lat_deg=29.5700184|lon_deg=31.2290955|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=[[Dahshur]]|position=right|mark=Blue pog.svg|lat_deg=29.78039307|lon_deg=31.21742016|label_size=50}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |Northern Egypt|label=[[Beni Hasan]]|position=right|mark=Blue pog.svg|lat_deg=27.933333|lon_deg=30.883333|label_size=50}} |

|||

}} |

|||

The length of time the Hyksos ruled is unclear. The fragmentary [[Turin King List]] says that there were six Hyksos kings who collectively ruled 108 years,{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=186}} however in 2018 Kim Ryholt proposed a new reading of as many as 149 years, while Thomas Schneider proposed a length between 160 and 180 years.{{sfn|Aston|2018|pp=31–32}} The rule of the Hyksos overlaps with that of the native Egyptian pharaohs of the [[Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Sixteenth]] and [[Seventeenth Dynasty of Egypt|Seventeenth]] Dynasties, better known as the [[Second Intermediate Period of Egypt|Second Intermediate Period]]. |

|||

The area under direct control of the Hyksos was probably limited to the eastern [[Nile delta]].{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=7}} Their capital city was [[Avaris]] at a fork on the now-dry Pelusiac branch of the Nile. [[Memphis, Egypt|Memphis]] may have also been an important administrative center,{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=183}} although the nature of any Hyksos presence there remains unclear.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=7}} |

|||

According to Anna-Latifa Mourad, other sites with likely Levantine populations or strong Levantine connections in the Delta include Tell Farasha and Tell el-Maghud, located between Tell Basta and Avaris,{{sfn|Mourad|2015|pp=43–44}} El-Khata'na, southwest of Avaris, and [[Inshas]].{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=48}} The increased prosperity of Avaris may have attracted more Levantines to settle in the eastern Delta.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=130}} Kom el-Hisn at the edge of the Western Delta, shows Near-Eastern goods but individuals mostly buried in an Egyptian style, which Mourad takes to mean that they were most likely Egyptians heavily influenced by Levantine traditions or, more likely, Egyptianized Levantines.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=49–50}} The site of [[Tell Basta]] (Bubastis), at the confluence of the Pelusiac and Tanitic branches of the Nile, contains monuments to the Hyksos kings Khyan and Apepi, but little other evidence of Levantine habitation.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=21}} Tell el-Habwa ([[Tjaru]]), located on a branch of the Nile near the Sinai, also shows evidence of non-Egyptian presence, however the majority of the population appears to have been Egyptian or Egyptianized Levantines.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|pp=44–48}} Tell El-Habwa would have provided Avaris with grain and trade goods.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|pp=129–130}} |

|||

[[File:Headband with Heads of Gazelles and a Stag Between Stars or Flowers ca. 1648–1540 BCE.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.2|Near-eastern inspired diadem with heads of gazelles and a stag between stars or flowers, belonging to an elite lady discovered at a tomb at [[Tell el-Dab'a]] (Avaris) dating from the late Hyksos period (1648–1540 BC).{{sfn|O'Connor|2009|pp=115–116}}{{sfn|Kopetzky|Bietak|2016|p=362}} Now at the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Hyksos headband |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544073 |website=www.metmuseum.org}}</ref>]] |

|||

In the [[Wadi Tumilat]], [[Tell el-Maskhuta]] shows a great deal of Levantine pottery and an occupation history closely correlated to the Fifteenth Dynasty,{{sfn|Mourad|2015|pp=51–55}} nearby Tell el-Rataba and Tell el-Sahaba show possible Hyksos-style burials and occupation,{{sfn|Mourad|2015|pp=56–57}} Tell el-Yahudiyah, located between Memphis and the Wadi Tumilat, contains a large earthwork that may have been built by the Hyksos, as well as evidence of Levantine burials from as early as the Thirteenth Dynasty.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|pp=57–61}} The Hyksos settlements in the Wadi Tumilat would have provided access to Sinai, the southern Levant, and possibly the [[Red Sea]].{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=130}} |

|||

The sites Tell el-Kabir, Tell Yehud, Tell Fawziya, and Tell Geziret el-Faras are noted by scholars other than Mourad to contain "elements of 'Hyksos culture'", but there is no published archaeological material for them.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=19}} |

|||

The Hyksos claimed to be rulers of both [[Lower Egypt|Lower]] and [[Upper Egypt]]; however, their southern border was marked at [[Hermopolis]] and [[Cusae]].{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=182}} Some objects might suggest a Hyksos presence in Upper Egypt, but they may have been Theban war booty or attest simply to short term raids, trade, or diplomatic contact.{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=3}} The nature of Hyksos control over the region of [[Thebes (Egypt)|Thebes]] remains unclear.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=7}} Most likely Hyksos rule covered the area from [[Middle Egypt]] to southern [[Palestine (region)|Palestine]].{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=2}} Older scholarship believed, due to the distribution of Hyksos goods with the names of Hyksos rulers in places such as [[Baghdad]] and [[Knossos]], that Hyksos had ruled a vast empire, but it seems more likely to have been the result of diplomatic gift exchange and far-flung trade networks.{{sfn|Morenz|Popko|2010|p=105}}{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=7}} |

|||

===Wars with the Seventeenth Dynasty=== |

|||

The conflict between Thebes and the Hyksos is known exclusively from pro-Theban sources, and it is difficult to construct a chronology.{{sfn|Morenz|Popko|2010|pp=108–109}} These sources propagandistically portray the conflict as a war of national liberation. This perspective was formerly taken by scholars as well but is no longer thought to be accurate.{{sfn|Morenz|Popko|2010|p=109}}{{sfn|Popko|2013|pp=1–2}} |

|||

Hostilities between the Hyksos and the Theban [[Seventeenth Dynasty of Egypt|Seventeenth Dynasty]] appear to have begun during the reign of Theban king [[Seqenenra Taa]]. Seqenenra Taa's mummy shows that he was killed by several blows of an axe to the head, apparently in battle with the Hyksos.{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=4}} It is unclear why hostilities may have started, but the much later fragmentary [[New Kingdom of Egypt|New Kingdom]] tale ''[[The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre]]'' blames the Hyksos ruler [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi/Apophis]] for initiating the conflict by demanding that Seqenenra Taa remove a pool of hippopotamuses near Thebes.{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=160}} However, this is a satire on the Egyptian story-telling genre of the "king's novel" rather than a historical text.{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=4}} A contemporary inscription at Wadi el Hôl may also refer to hostilities between Seqenenra and Apepi.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=5}} |

|||

[[File:Sequenre tao.JPG|thumb|Mummified head of [[Seqenenra Taa]], bearing axe wounds. The common theory is that he died in a battle against the Hyksos.{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=160}}]] |

|||

Three years later, c. 1542 BC,{{sfn|Stiebing|2009|p=200}} Seqenenra Taa's successor [[Kamose]] initiated a campaign against several cities loyal to the Hyksos, the account of which is preserved on three monumental stelae set up at [[Karnak]].{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=161}}{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=5}}{{sfn|Wilkinson|2013|p=547}} The first of the three, [[Carnarvon Tablet]] includes a complaint by Kamose about the divided and occupied state of Egypt: |

|||

<blockquote>To what effect do I perceive it, my might, while a ruler is in Avaris and another in Kush, I sitting joined with an Asiatic and a Nubian, each man having his (own) portion of this Egypt, sharing the land with me. There is no passing him as far as Memphis, the water of Egypt. He has possession of Hermopolis, and no man can rest, being deprived by the levies of the Setiu. I shall engage in battle with him and I shall slit his body, for my intention is to save Egypt, striking the Asiatics.{{sfn|Ritner|Simpson|Tobin|Wente|2003|p=346}}</blockquote> |

|||

Following a common literary device, Kamose's advisors are portrayed as trying to dissuade the king, but the king attacks anyway.{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=161}} He recounts his destruction of the city of [[Nefrusy]] as well as several other cities loyal to the Hyksos. On a second stele, Kamose claims to have captured Avaris, but returned to Thebes after capturing a messenger between Apepi and the king of [[Kingdom of Kerma|Kush]].{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=4}} Kamose appears to have died soon afterward (c. 1540 BC).{{sfn|Stiebing|2009|p=200}} |

|||

[[Ahmose I]] continued the war against the Hyksos, most likely conquering Memphis, [[Tjaru]] and [[Heliopolis (ancient Egypt)|Heliopolis]] early in his reign, the latter two of which are mentioned in an entry of the [[Rhind mathematical papyrus]].{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=4}} Knowledge of Ahmose I's campaigns against the Hyksos mostly comes from the tomb of [[Ahmose, son of Ebana]], who gives a first person account claiming that Ahmose I sacked Avaris:{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=177}} |

|||

<blockquote>Then there was fighting in Egypt to the south of this town [Avaris], and I carried off a man as a living captive. I went down into the water—for he was captured on the city side—and crossed the water carrying him. [...] Then Avaris was despoiled, and I brought spoil from there.{{sfn|Lichthelm|2019|p=321}}</blockquote> |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| perrow = 2 |

|||

| total_width = 300 |

|||

| caption_align = center |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction = horizontal |

|||

| image1 = Ceremonial axe of Ahmose I (front and back).jpg |

|||

| image2 = Pharaoh_Ahmose_I_slaying_a_Hyksos_(axe_of_Ahmose_I,_from_the_Treasure_of_Queen_Aahhotep_II)_Colorized_per_source.jpg |

|||

| footer = Pharaoh [[Ahmose I]] (ruled c. 1549–1524 BC) slaying a probable Hyksos. Detail of a ceremonial axe in the name of Ahmose I, treasure of Queen [[Ahhotep II]]. Inscription "Ahmose, beloved of (the War God) [[Montu]]". [[Luxor Museum]]{{sfn|Daressy|1906|p=117}}<ref>{{harvnb|Montet|1968|p=80|ps=. "Others were later added to them, things which came from the pharaoh Ahmose, like the axe decorated with a griffin and a likeness of the king slaying a Hyksos, with other axes and daggers."}}</ref>{{sfn|Morgan|2010|p=308|ps=. A color photograph.}}{{sfn|Baker|Baker|2001|p=86}} |

|||

| footer_align = center |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| caption1 = |

|||

| caption2 = |

|||

}} |

|||

Thomas Schneider places the conquest in year 18 of Ahmose's reign.{{sfn|Schneider|2006|p=195}} However, excavations of [[Tell El-Dab'a]] (Avaris) show no widespread destruction of the city, which instead seems to have been abandoned by the Hyksos.{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=4}} Manetho, as recorded in Josephus, states that the Hyksos were allowed to leave after concluding a treaty:{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|pp=201–202}} |

|||

<blockquote>Thoumosis ... invested the walls [of Avaris] with an army of 480,000 men, and endeavoured to reduce [the Hyksos] to submission by siege. Despairing of achieving his object, he concluded a treaty, under which [the Hyksos] were all to evacuate Egypt and go whither they would unmolested. Upon these terms no fewer than two hundred and forty thousand, entire households with their possessions, left Egypt and traversed the desert to Syria. (''Contra Apion'' I.88-89){{sfn|Josephus|1926|pp=197–199}}</blockquote> |

|||

Although Manetho indicates that the Hyksos population was expelled to the Levant, there is no archaeological evidence for this, and Manfred Bietak argues on the basis of archaeological finds throughout Egypt that it is likely that numerous Asiatics were resettled in other locations in Egypt as artisans and craftsmen.{{sfn|Bietak|2010|pp=170–171}} Many may have remained at Avaris, as pottery and scarabs with typical "Hyksos" forms continued to be produced uninterrupted throughout the Eastern Delta.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=5}} Canaanite cults also continued to be worshiped at Avaris.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=6}} |

|||

Following the capture of Avaris, Ahmose, son of Ebana records that Ahmose I captured [[Sharuhen]] (possibly [[Tell el-Ajjul]]), which some scholars argue was a city in Canaan under Hyksos control.{{sfn|Stiebing|2009|p=168}} |

|||

==Rule and administration== |

|||

[[File:Asiatic official Munich (retouched).jpg|thumb|An official wearing the "mushroom-headed" hairstyle also seen in contemporary paintings of Western Asiatic foreigners such as in the tomb of [[Khnumhotep II]], at [[Beni Hasan]]. Excavated in [[Avaris]], the Hyksos capital. Dated to 1802–1640 BC. [[Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Candelora |first1=Danielle |title=The Hyksos |url=https://www.arce.org/resource/hyksos |website=www.arce.org |publisher=American Research Center in Egypt}}</ref>{{sfn|Roy|2011|pp=291–292}}<ref>{{harvnb|Curry|2018|p=[https://www.archaeology.org/issues/309-1809/features/6855-egypt-hyksos-foreign-dynasty#art_page3 3] |ps=. "A head from a statue of an official dating to the 12th or 13th Dynasty (1802–1640 B.C.) sports the mushroom-shaped hairstyle commonly worn by non-Egyptian immigrants from western Asia such as the Hyksos."}}</ref>{{sfn|Potts|2012|p=841}}]] |

|||

===Administration=== |

|||

The Hyksos show a mix of Egyptian and Levantine cultural traits.{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=182}} Their rulers adopted the full [[Ancient Egyptian royal titulary]] and employed Egyptian scribes and officials.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=3}} They also used Near-Eastern forms of administration, such as employing a chancellor ({{lang|egy|imy-r khetemet|italics=yes}}) as the head of their administration.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|pp=3–4}} |

|||

===Rulers=== |

|||

The names, the order, length of rule, and even the total number of the Fifteenth Dynasty rulers are not known with full certainty. After the end of their rule, the Hyksos kings were not considered to have been legitimate rulers of Egypt and were therefore omitted from most king lists.{{sfn|Ben-Tor|2007|p=2}} The fragmentary [[Turin King List]] included six Hyksos kings, however only the name of the last, [[Khamudi]], is preserved.{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=118}} Six names are also preserved in the various epitomes of Manetho, however, it is difficult to reconcile the Turin King List and other sources with names known from Manetho,{{sfn|Bietak|1999|p=378}} largely due to the "corrupted name forms" in Manetho.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=1}} The name [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi/Apophis]] appears in multiple sources, however.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|pp=7–8}} |

|||

Various other archaeological sources also provide names of rulers with the Hyksos title,{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=179}} however, the majority of kings from the second intermediate period are attested once on a single object, with only three exceptions.{{sfn|Ryholt|2018|p=235}} Ryholt associates two other rulers known from inscriptions with the dynasty, [[Khyan]] and [[Sakir-Har]].{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|pp=119–120}} The name of Khyan's son, [[Yanassi]], is also preserved from Tell El-Dab'a.{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=180}} The two best attested kings are Khyan and Apepi.{{sfn|Aston|2018|p=18}} Scholars generally agree that Apepi and Khamudi are the last two kings of the dynasty,{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|pp=6–7}} and Apepi is attested as a contemporary of Seventeenth-Dynasty pharaohs [[Kamose]] and [[Ahmose I]].{{sfn|Aston|2018|p=16}} Ryholt has proposed that Yanassi did not rule and that Khyan directly preceded Apepi,{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=256}} but most scholars agree that the order of kings is: Khyan, Yanassi, Apepi, Khamudi.{{sfn|Aston|2018|pp=15–17}} There is less agreement on the early rulers. Sakir-Har is proposed by Schneider, Ryholt, and Bietak to have been the first king.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=4}}{{sfn|Schneider|2006|p=194}}{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=201}} |

|||

Recently, archaeological finds have suggested that Khyan may actually have been a contemporary of Thirteenth-Dynasty pharaoh [[Sobekhotep IV]], potentially making him an early rather than a late Hyksos ruler.{{sfn|Aston|2018|p=15}} This has prompted attempts to reconsider the entire chronology of the Hyksos period, which as of 2018 had not yet reached any consensus.{{sfn|Polz|2018|p=217}} |

|||

Some kings are attested from either fragments of the Turin King List or from other sources who may have been Hyksos rulers. According to Ryholt, kings [[Semqen]] and [[Aperanat]], known from the Turin King List, may have been early Hyksos rulers,{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|pp=121–122}} however [[Jürgen von Beckerath]] assigns these kings to the [[Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt]].{{sfn|von Beckerath|1999|pp=120–121}} Another king known from [[scarab (artifact)|scarabs]], [[Sheshi]],{{sfn|Bietak|1999|p=378}} is believed by many scholars to be a Hyksos king,{{sfn|Müller|2018|p=210}} however Ryholt assigns this king to the Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt.{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=409}} Manfred Bietak proposes that a king recorded as [[Yaqub-Har]] may also have been a Hyksos king of the Fifteenth Dynasty.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=2}} Bietak suggests that many of the other kings attested on [[scarab (artifact)|scarabs]] may have been vassal kings of the Hyksos.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|pp=2–3}} |

|||

{| class="wikitable" width="90%" |

|||

|+Hyksos rulers in various sources{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=4}}{{sfn|Schneider|2006|p=194}}{{sfn|Aston|2018|p=17}} |

|||

! Manetho{{sfn|Redford|1992|p=107}} |

|||

! Turin King List |

|||

! [[Genealogy of Ankhefensekhmet]] |

|||

! Identification by Redford (1992){{sfn|Redford|1992|p=110}} |

|||

! Identification by Ryholt (1997){{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=125}} |

|||

! Identification by Bietak (2012){{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=4}} |

|||

! Identification by Schneider (2006) (reconstructed Semitic name in parentheses){{sfn|Aston|2018|p=17}}{{sfn|Schneider|2006|pp=193–194}}{{efn|While Schneider identifies each of the names in Menatho with a pharaoh, he does not hold to Manetho's order of the reigns. So, for instance, he identifies Sakir-Har with Archles/Assis, the sixth king in Manetho, but proposes he reigned first.{{sfn|Schneider|2006|p=–194}}}} |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| Salitis/Saites (19 years) |

|||

! Name |

|||

| X 15 |

|||

! Dates |

|||

| [[Sharek|Schalek]]{{efn|Identified with Salitis by Bietak.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=4}}}} |

|||

| Sheshi |

|||

| ?Semqen (Šamuqēnu)? |

|||

| ?Sakir-Har? |

|||

| ? (Šarā-Dagan [Šȝrk[n]]) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| Bnon (44 years) |

|||

| [[Sakir-Har]] |

|||

| X 16.... 3 years |

|||

| Named as an early Hyksos king on a door jamb found at [[Avaris]]. </br>Regnal order uncertain. |

|||

| |

|||

| Yaqub-Har |

|||

| ?Aper-Anat ('Aper-'Anati)? |

|||

|?Meruserre Yaqub-Har? |

|||

| ? (*Bin-ʿAnu) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| Apachnan/Pachnan (36/61 years) |

|||

| [[Khyan]] |

|||

| X 17... 8 years 3 months |

|||

| c. [[1620 BC]] |

|||

| |

|||

| Khyan |

|||

| Sakir-Har |

|||

| Seuserenre Khyan |

|||

| Khyan ([ʿApaq-]Hajran) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| Iannas/Staan (50 years) |

|||

| [[Apepi I|Apophis]] |

|||

| |

| X 18... 10 (20, 30) years |

||

| |

|||

| Yanassi (Yansas-X) |

|||

| Khyan |

|||

| Yanassi (Yansas-idn) |

|||

| Yanassi (Jinaśśi’-Ad) |

|||

|- |

|||

| Apophis (61/14 years) |

|||

| X 19... 40 + x years |

|||

| Apepi (?'A-ken?){{efn|This name appears as a separate individual preceding Apepi, but it appears to mean "brave ass" and may be a disparaging reference to Apepi.{{sfn|Redford|1992|p=108}}}} |

|||

| Apepi |

|||

| Apepi |

|||

| A-user-Re Apepi |

|||

| Apepi (Apapi) |

|||

|- |

|||

|- |

|||

| rowspan="2" | Archles/Assis (40/30 years){{efn|In Eusebius and Africanus's epitomes of Manetho, "Apopis" appears in final position, while Archles appears as the fifth ruler. In Josephus, Assis is the final ruler and Apophis the fifth ruler. The association of the names Archles and Assis with one another is a modern reconstruction.{{sfn|Redford|1992|p=107}}}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| ''identifies with ?Khamudi?'' |

|||

| ''identifies with Khamudi'' |

|||

| ''Identifies with Khamudi'' |

|||

| Sakir-Har (Sikru-Haddu) |

|||

|- |

|||

|X 20 Khamudi |

|||

| |

|||

| ?Khamudi?{{efn|Redford argues that the name "suits neither Assis nor Apophis".{{sfn|Redford|1992|p=108}}}} |

|||

| Khamudi |

|||

| Khamudi |

|||

| ''not in Manetho'' (Halmu'di) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|Sum: 259 years{{efn|In the epitome of Manetho by [[Eusebius]], the total instead comes to 284 years.{{sfn|Schneider|2006|p=194}}}} |

|||

| [[Khamudi]] |

|||

|Sum: 108 years{{efn|This reading is based on a partially damaged section of the papyrus. Reconstructions of the damaged Turin King List proposed in 2018 would change the reading of years to up to 149 years (Ryholt) or between 160 and 180 years (Schneider).{{sfn|Aston|2018|pp=31–32}}}} |

|||

| c. [[1540 BC]] to [[1534 BC]] |

|||

|||||||||| |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

None of the proposed identifications besides of Apepi and Apophis is considered certain.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=11}} |

|||

The rule of these kings overlaps with that of the native Egyptian pharaohs of the [[Sixteenth dynasty of Egypt|16th]] and [[Seventeenth dynasty of Egypt|17th dynasties]] of Egypt, better known as the [[Second Intermediate Period of Egypt|Second Intermediate Period]]. The first pharaoh of the [[Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt|18th dynasty]], [[Ahmose I]], finally expelled the Hyksos from their last holdout at [[Sharuhen]] in [[Gaza]] by the 16th year of his reign.<ref>Grimal, Nicolas. ''A History of Ancient Egypt.'' p.193. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988.</ref><ref>Redford, Donald B. ''History and Chronology of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt: Seven Studies'', pp.46–49. University of Toronto Press, 1967.</ref> |

|||

In [[Sextus Julius Africanus]]'s epitome of Manetho, the rulers of [[Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Sixteenth Dynasty]] are also identified as "shepherds" (i.e. Hyksos) rulers.{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=179}} Following the work of Ryholt in 1997, most but not all scholars now identify the Sixteenth Dynasty as a native Egyptian dynasty based in [[Thebes, Egypt|Thebes]], following [[Eusebius]]'s epitome of Manetho; this dynasty would be contemporary to the Hyksos.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=3}} |

|||

Scholars have taken the increasing use of scarabs and the adoption of some Egyptian forms of art by the Fifteenth Dynasty Hyksos kings and their wide distribution as an indication of their becoming progressively Egyptianized.<ref>Booth, Charlotte. <cite>The Hyksos Period in Egypt</cite>. p.15-18. Shire Egyptology. 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1</ref> The Hyksos used Egyptian titles associated with traditional Egyptian kingship, and took Egyptian god [[Set (mythology)|Seth]] to represent their own titulary deity.<ref>Booth, Charlotte. <cite>The Hyksos Period in Egypt</cite>. p.29-31. Shire Egyptology. 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1</ref> It would appear as though Hyksos administration was accepted in most quarters, if not actually supported by many of their northern Egyptian subjects. The flip side is that in spite of the prosperity that the stable political situation brought to the land, the native [[Egyptians]] continued to view the Hyksos as non-Egyptian "invaders." When they eventually were driven out of Egypt, all traces of their occupation were erased. History is written by the victors, and in this case the victors were the rulers of the native Egyptian Eighteenth Dynasty, the direct successor of the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty. It was the latter which started and led a sustained war against the Hyksos. These native kings from Thebes had an incentive to demonize the Asiatic rulers in the North, thus accounting for the ruthless destruction of their monuments. This note of warning tells us that the historical situation most probably lay somewhere between these two extreme positions: the Hyksos dynasties represented superficially Egyptianized foreigners who were tolerated, but not truly accepted, by their Egyptian subjects. |

|||

===Diplomacy=== |

|||

The independent native rulers in Thebes do seem, however, to have reached a practical ''modus vivendi'' with the later Hyksos rulers. This included transit rights through Hyksos-controlled Middle and [[Lower Egypt]] and pasturage rights in the fertile Delta. One text, the ''Carnarvon Tablet I,'' relates the misgivings of the Theban ruler’s council of advisors when [[Kamose]] proposed moving against the Hyksos, who he claimed were a humiliating stain upon the holy land of Egypt. The councilors clearly did not wish to disturb the status quo: |

|||

[[File:Khyan.jpg|thumb|Lion inscribed with the name of the Hyksos ruler [[Khyan]], found in [[Baghdad]], suggesting [[Egypt–Mesopotamia relations|relations with Babylon]]. The prenomen of Khyan and epithet appear on the breast. [[British Museum]], EA 987.{{sfn|Weigall|2016|p=188}}<ref name="Statue British Museum">{{cite web |title=Statue |id=EA987 |url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA987 |website=The British Museum}}</ref>]] |

|||

The Hyksos engagement in long-distance diplomacy is confirmed by a [[cuneiform]] letter discovered in the ruins of Avaris. Hyksos diplomacy with [[Crete]] and [[ancient Near East]] is also confirmed by the presence of gifts from the Hyksos court in those places.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=4}} [[Khyan]], one of the Hyksos rulers, is known for his wide-ranging contacts, as objects in his name have been found at [[Knossos]] and [[Hattusha]] indicating diplomatic contacts with Crete and the [[Hittites]], and a sphinx with his name was bought on the art market at [[Baghdad]] and might demonstrate [[Egypt–Mesopotamia relations|diplomatic contacts with Babylon]], possibly with the first [[Kassites]] ruler [[Gandash]].{{sfn|Weigall|2016|p=188}}<ref name="Statue British Museum"/> |

|||

The Theban rulers of the Seventeenth Dynasty are known to have imitated the Hyksos both in their architecture and regnal names.{{sfn|Morenz|Popko|2010|p=108}} There is evidence of friendly relations between the Hyksos and Thebes, including possibly a marriage alliance, prior to the reign of the Theban pharaoh [[Seqenenra Taa]].{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=160}} |

|||

{{cquote|… we are at ease in our (part of) Egypt. Elephantine (at the First Cataract) is strong, and the middle (of the land) is with us as far as Cusae [near modern Asyut]. The sleekest of their fields are plowed for us, and our cattle are pastured in the Delta. Emmer is sent for our pigs. Our cattle have not been taken away… He holds the land of the Asiatics; we hold Egypt…"<ref name = "Pritchard 232">Pritchard (ed.), ''Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament'' (ANET), pp 232f.</ref>}} |

|||

An intercepted letter between Apepi and the [[Nubia]]n King of [[Kingdom of Kerma|Kerma]] (also called Kush) to the south of Egypt recorded on the Carnarvon Tablet has been interpreted as evidence of an alliance between the Hyksos and Kermans.{{sfn|Stiebing|2009|p=168}} Intensive contacts between Kerma and the Hyksos are further attested by seals with the names of Asiatic rulers or with designs known from Avaris at Kerma.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=9}} The troops of Kerma are known to have raided as far north as [[Elkab]] according to an inscription of [[Sobeknakht II]].{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=4}} According to his second stele, Kamose was effectively caught between the campaign for the siege of Avaris in the north and the offensive of Kerma in the south; it is unknown whether or not the Kermans and Hyksos were able to combine forces against him.{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=161}} Kamose reports returning "in triumph" to Thebes, but Lutz Popko suggests that this "was perhaps a mere tactical retreat to prevent a war on two fronts".{{sfn|Popko|2013|p=4}} Ahmose I was also forced to confront a threat from the Nubians during his own siege of Avaris: he was able to stop the forces of Kerma by sending a strong fleet, killing their ruler named A'ata.{{sfn|Bunson|2014|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=-6EJ0G-4jyoC&pg=PA2 2–3]}}{{sfn|Bunson|2014|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=-6EJ0G-4jyoC&pg=PA197 197]}} Ahmose I boasts about these successes on his tomb at Thebes.{{sfn|Bunson|2014|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=-6EJ0G-4jyoC&pg=PA2 2–3]}} The Kermans also appear to have provided mercenaries to the Hyksos.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=4}} |

|||

==Was there a Hyksos invasion?== |

|||

[[Manetho]]'s account of the appearance of the Hyksos in Egypt describes it as an armed invasion by a horde of foreign barbarians who met little resistance and who subdued the country by military force. It has been claimed that new revolutionary methods of warfare ensured the Hyksos the ascendancy in their invasion. [[Herbert E. Winlock]] describes new military hardware, such as the [[composite bow]], as well as the improved [[recurve bow]] and most importantly the horse-drawn war [[chariot]], as well as improved arrowheads, various kinds of swords and daggers, a new type of shield, [[Mail (armour)|mailed shirts]], and the metal helmet.<ref name = "Winlock">Winlock, Herbert E. ''The Rise and Fall of the Middle Kingdom in Thebes''.</ref> |

|||

===Vassalage=== |

|||

The traditional explanation is that there was an invasion; one that took several years and that wasn't a coordinated effort of some foreign kingdom, but mostly a migration of particular groups, tribes or federated tribes, which had access to new and superior weapons developed further away in Asia that helped them conquer a rich piece of land to live in, and were possibly being routed from their own areas. |

|||

Many scholars have described the Egyptian dynasties contemporary to the Hyksos as "vassal" dynasties, an idea partially derived from the [[Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt|Nineteenth-Dynasty]] literary text ''[[The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre]]'',{{sfn|Flammini|2015|pp=236–237}} in which it is said "the entire land paid tribute to him [Apepi], delivering their taxes in full as well as bringing all good produce of Egypt."{{sfn|Ritner|Simpson|Tobin|Wente|2003|p=70}} The belief in Hyksos vassalage was challenged by Ryholt as "a baseless assumption."{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=323}} Roxana Flammini suggests instead that Hyksos exerted influence through (sometimes imposed) personal relationships and gift-giving.{{sfn|Flammini|2015|pp=239–243}} Manfred Bietak continues to refer to Hyksos vassals, including minor dynasties of West Semitic rulers in Egypt.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|pp=1–4}} |

|||

==Society and culture== |

|||

In the last decades, however, the idea of a simple migration, with little or no violence involved, has gained some support.<ref>Booth, Charlotte. <cite>The Hyksos Period in Egypt</cite>. p.10. Shire Egyptology, 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1</ref> Under this theory, the Egyptian rulers of [[Thirteenth dynasty of Egypt|13th Dynasty]] were unable to stop these new migrants from travelling to Egypt from Asia because they were weak kings who were struggling to cope with various domestic problems including possibly famine. The ceramic evidence in the Memphis-Fayum region of Lower Egypt also strongly argues against the presence of new invading foreigners. Indeed, Janine Bourriau's excavation from Memphis as well as her study of ceramic material retrieved from Lisht and [[Dahshur]] during the Second Intermediate Period shows a continuity of Middle Kingdom ceramic type wares throughout this era with little to no evidence of intrusion of Hyksos-style wares.<ref>The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer Oren, University of Pennsylvania 1997. cf. Janine Bourriau's chapter of the archaeological evidence covers pages 159-182</ref> Bourriau's evidence militates against the traditional Egyptian view--as espoused by Manetho--that the Hyksos invaded and sacked the Memphite region and imposed their authority there. Not until the beginning of the Theban wars of liberation during the 17th Dynasty are Theban wares found in the Fayum-Memphis region which indicates that the Hyksos controlled the Delta region while Middle Egypt and the Thebaid functioned autonomously and shared limited contact with each other.<ref>James K. Hoffmeier, Book Review of 'The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer Oren, University of Pennsylvania 1997.' in JEA 90 (2004), p.27</ref> |

|||

===Royal construction and patronage=== |

|||

{{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=420|caption_align=center |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction =horizontal |

|||

| header=The so-called "Hyksos Sphinxes" |

|||

| image1 = Hyksos Sphinxes.jpg |

|||

| image2 = Sphinx Amenemhat3 Budge.jpg |

|||

| footer=The so-called "Hyksos Sphinxes" are peculiar sphinxes of [[Amenemhat III]] which were reinscribed by several Hyksos rulers, including [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi]]. Earlier Egyptologists thought these were the faces of actual Hyksos rulers.{{sfn|el-Shahawy|2005|p=160}} |

|||

}} |

|||

[[File:Statue Khyan CG389 Naville.jpg|thumb|upright|Remains of a statue of the [[Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt|Twelfth Dynasty]] reappropriated by Hyksos ruler "[[Khyan]]", with his name inscribed on the sides over an erasure.{{sfn|Griffith|1891|p=28|ps=. "The name of Khyan on the statue from Bubastis is written over an erasure, that the statue is of the XIIth Dynasty, and that Khyan was a Hyksôs king."}}]] |

|||

The Hyksos do not appear to have produced any court art,{{sfn|Bietak|1999|p=379}} instead appropriating monuments from earlier dynasties by writing their names on them. Many of these are inscribed with the name of King [[Khyan]].{{sfn|Müller|2018|p=212}} A large palace at Avaris has been uncovered, built in the Levantine rather than the Egyptian style, most likely by Khyan.{{sfn|Bard|2015|p=213}} King [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi]] is known to have patronized Egyptian scribal culture, commissioning the copying of the [[Rhind Mathematical Papyrus]].{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|pp=151–153}} The stories preserved in the [[Westcar Papyrus]] may also date from his reign.{{sfn|Redford|1992|p=122}} |

|||

The so-called "[[Commons:Category:Hyksos sphinxes of Amenemhat III|Hyksos sphinxes]]" or "Tanite sphinxes" are a group of royal sphinxes depicting the earlier pharaoh [[Amenemhat III]] (Twelfth Dynasty) with some unusual traits compared to conventional statuary, for example prominent cheekbones and the thick mane of a lion, instead of the traditional [[nemes]] headcloth. The name "Hyksos sphinxes" was given due to the fact that these were later reinscribed by several of the Hyksos kings, and were initially thought to represent the Hyksos kings themselves. Nineteenth-century scholars attempted to use the statues' features to assign a racial origin to the Hyksos.{{sfn|Candelora|2018|p=54}} These Sphinxes were seized by the Hyksos from cities of the [[Middle Kingdom of Egypt|Middle Kingdom]] and then transported to their capital [[Avaris]] where they were reinscribed with the names of their new owners and adorned their palace.{{sfn|el-Shahawy|2005|p=160}} Seven of those sphinxes are known, all from [[Tanis]], and now mostly located in the [[Cairo Museum]].{{sfn|el-Shahawy|2005|p=160}}{{sfn|Sayce|1895|p=17}} [[:File:Statues of Shepherd Kings by Boston Public Library.jpg|Other statues of Amenehat III]] were found in Tanis and are associated with the Hyksos in the same manner. |

|||

At some point in time, the foreigners, whose elite might have already been local rulers in the name of the Pharaoh, realized there was no need to pay tribute and obedience to a weak king, and took the title of Pharaoh for themselves. (in the north of the country — the Hyksos never penetrated the south) |

|||

===Burial practices=== |

|||

Josephus, quoting from the work of the historian Manetho, described the invasion: |

|||

Evidence for distinct Hyksos burial practices in the archaeological record include burying their dead within settlements rather than outside them like the Egyptians.{{sfn|Bietak|2016|p=268}} While some of the tombs include Egyptian-style chapels, they also include burials of young females, probably sacrifices, placed in front of the tomb chamber.{{sfn|Bard|2015|p=213}} There are also no surviving Hyksos funeral monuments in the desert in the Egyptian style, though these may have been destroyed.{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=183}} The Hyksos also interred infants who died in imported Canaanite amphorae.{{sfn|Wilkinson|2013|p=191}} The Hyksos also practiced [[horse burial|the burial of horses]] and other [[equid]]s, likely a composite custom of the Egyptian association of the god [[Set (god)|Set]] with the [[donkey]] and near-eastern notions of equids as representing status.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=15}} |

|||

===Technology=== |

|||

{{cquote|By main force they easily seized it without striking a blow; and having overpowered the rulers of the land, they then burned our cities ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of gods… Finally, they appointed as king one of their number whose name was Salitis.}} |

|||

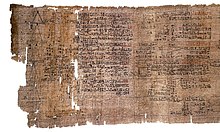

[[File:Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.jpg|thumb|The [[Rhind Mathematical Papyrus]] was copied for the Hyksos king [[Apepi (pharaoh)|Apepi]].]] |

|||

The Hyksos use of horse burials suggest that the Hyksos introduced both the [[horse]] and the [[chariot]] to Egypt,{{sfn|Hernández|2014|p=112}} however no archaeological, pictorial, or textual evidence exists that the Hyksos possessed chariots, which are first mentioned as ridden by the Egyptians in warfare against them by [[Ahmose, son of Ebana]], at the close of Hyksos rule.{{sfn|Herslund|2018|p=151}} In any case, it does not appear that chariots played any large role in the Hyksos rise to power or their expulsion.{{sfn|Stiebing|2009|p=166}} Josef Wegner further argues that [[Domestication of the horse|horse-riding]] may have been present in Egypt as early as the late Middle Kingdom, prior to the adoption of chariot technology.{{sfn|Wegner|2015|p=76}} |

|||

Traditionally, the Hyksos have also been credited with introducing a number of other military innovations, such as the [[sickle-sword]] and [[composite bow]]; however, "[t]o what extent the kingdom of Avaris should be credited for these innovations is debatable," with scholarly opinion currently divided.{{sfn|Ilin-Tomich|2016|p=12}} It is also possible that the Hyksos introduced more advanced bronze working techniques, though this is inconclusive. They may have worn full-body armor,{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=149}} whereas the Egyptians did not wear armor or helmets until the New Kingdom.<ref name="Hyksos axe">{{cite web |title=Hyksos axe |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/545716 |website=www.metmuseum.org}}</ref> |

|||

Supporters of the peaceful takeover of Egypt claim that there is little evidence of battles or wars in general in this period.<ref>Booth, Charlotte. <cite>The Hyksos Period in Egypt</cite>. p.10. Shire Egyptology. 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1</ref> They also maintain that the chariot didn't play any relevant role, e.g. there no traces of chariots have been found at the Hyksos capital of Avaris despite extensive excavation.<ref>{{cite book | last = Bard | first = Kathryn | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt | publisher = Routledge | date = 1999 | location = | pages = 225 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=PG6HffPwmuMC&pg=PA225&dq=chariots+Hyksos&ei=e5VWSJeiK4SgiwHyyJWJDA&client=firefox-a&sig=flo-c4bmqFigrBkxn8F02f8J5eM#PPA225,M1 | doi = | id = | isbn = 978-0415185899 }}</ref> This puts in doubt claims of technological superiority on the Hyksos side. The case for the invasion, on the other side, is based mostly on: (a) the traditional Manetho's explanation; (b) the fact that the chariot was a new technology spreading from [[Central Asia]] and that there are other theories of invasions by nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes mounted on chariots in 1700–1300 BC, most notably [[Hurrians]] in the [[Near East]] (Helck) and [[Aryans]] in [[India]] (the [[Vedas]]), with the Hurrians in particular being active quite near where the Hyksos appeared; and (c) the fact that the chariot became the master weapon of that period, the weapon of nobles and kings, and one of the most important symbols of power in [[Eurasia]], because in [[Mycenaean Greece]], [[India]], [[Mesopotamia]], [[Eastern Europe]] and [[China]], kings and gods started to be portrayed on chariots, buried in chariots and always went to war in chariots. With such an important new weapon, the advocates of the invasion theory say, it seems strange to consider that the Hyksos just entered peacefully in the north of Egypt from Asia, with no knowledge of the chariot, or knowing it but choosing not to use it. Hence, the Egyptian description of the Hyksos was likely propaganda. |

|||

The Hyksos also introduced better weaving techniques and new musical instruments to Egypt.{{sfn|Van de Mieroop|2011|p=149}} They introduced improvements in [[viniculture]] as well.{{sfn|Bietak|2012|p=5}} |

|||

== Theban offensive == |

|||

===Under Seqenenre Tao (II)=== |

|||

[[Image:TaoII-mummy-head.png|200px|thumb|Drawing of the mummified head of Tao II, bearing axe-blade wounds. The common theory is that he died in a battle against the Hyksos]] |

|||

The war against the Hyksos began in the closing years of the Seventeenth Dynasty at Thebes. Later New Kingdom literary tradition has brought one of these Theban kings, [[Tao II the Brave|Seqenenre Tao (II)]], into contact with his Hyksos contemporary in the north, [[Apepi I|Auserra Apophis]] (also known as Apepi or Apophis). The tradition took the form of a tale in which the Hyksos king Apopi sent a messenger to Seqenenre in Thebes to demand that the Theban sport of harpooning hippopotami be done away with, his excuse was that the noise of these beasts was such that he was unable to sleep in far-away [[Avaris]]. The real reason was probably that their main god was [[Set (mythology)|Seth]], who was represented as part man part hippopotamus. Perhaps the only historical information that can be gleaned from the tale is that Egypt was a divided land, the area of direct Hyksos control being in the north, but the whole of Egypt possibly paying tribute to the Hyksos kings. |

|||

<gallery widths="200" heights="160"> |

|||

Seqenenre participated in active diplomatic posturing, which probably consisted of more than simply exchanging insults with the Asiatic ruler in the North. He seems to have led military skirmishes against the Hyksos, and judging by the vicious head wound on his [[mummy]] in the [[Cairo Museum]], he may have died during one of them. His son and successor, [[Kamose|Wadjkheperra Kamose]], the last ruler of the [[Seventeenth dynasty of Egypt|Seventeenth Dynasty]] at [[Thebes, Egypt|Thebes]], is credited with the first significant victories in the Theban-led war against the Hyksos. |

|||

File:Egyptian duckbill-shaped axe blade of Syro-Palestinian type 1981-1550 BCE.jpg|Egyptian duckbill-shaped axe blade of Syro-Palestinian type, a lethal technology probably introduced by the Hyksos (1981–1550 BC).<ref name="Hyksos axe"/> |

|||

File:Hyksos spearhead (1780-1580 BCE).jpg|A bronze Hyksos-period spearhead, found in [[Lachish]] (1780–1580 BC).<ref>{{cite web |title=Spearhead |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/323111 |website=www.metmuseum.org}}</ref> |

|||

File:Whip Handle in the Shape of a Horse 1390-1353 BCE.jpg|The horse was probably introduced to Egypt by the Hyksos, and became a favourite subject of Egyptian art, as in this whip handle from the reign of [[Amenhotep III]] (1390–1353 BC).<ref>{{cite web |title=Whip handle |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544853 |website=www.metmuseum.org}}</ref> |

|||

File:Chariot of Tutankhamun.jpg|The two-wheeled horse chariot, here found in the tomb of [[Tutankhamun]], may have been introduced to Egypt by the Hyksos.{{sfn|Hernández|2014|p=112}} |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== |

===Trade and economy=== |

||

[[File:"Tell el-Yahudiya" Vase in the Shape of a Duck MET 23.3.40 left.jpg|thumb|upright|An example of Egyptian [[Tell el-Yahudiyeh Ware]], a Levantine-influenced style.]] |

|||

There is little evidence to support [[Pierre Montet]]'s assertion in his 1964 book ''Eternal Egypt'' that Kamose's war of liberation was sponsored by the priests of Amun as an attack against the Seth-worshipers in the north (i.e. a religious motive). The Carnarvon Tablet I, does state that Kamose travelled north to attack the Asiatics by the command of Amun, the titulary deity of his dynasty, but this is simple hyperbole common to virtually all Egyptian royal inscriptions at all periods of time and should not be understood as the god’s having specifically commanded the attack itself for religious reasons. Kamose's reason for launching his attack on the Hyksos was nationalistic pride, for in this same text he complains that he is sandwiched at Thebes between the Asiatics in the north and the [[ancient Nubians|Nubians]] in the south, each holding "his slice of Egypt, dividing up the land with me… My wish is to save Egypt and to smite the Asiatics!" Hence, it was native Egyptian nationalism that prompted Kamose to embark and sailed north from Thebes at the head of his army in his third regnal year. |

|||

The early period of Hyksos period established their capital of Avaris "as the commercial capital of the Delta".{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=129}} The trading relations of the Hyksos were mainly with [[Canaan]] and [[Cyprus]].{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=182}}{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|pp=138–139, 142}} Trade with Canaan is said to have been "intensive", especially with many imports of Canaanite wares, and may have reflected the Canaanite origins of the dynasty.{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|pp=138–139}} Trade was mostly with the cities of the northern Levant, but connections with the southern Levant also developed.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=216}} Additionally, trade was conducted with [[Faiyum]], [[Memphis (Egypt)|Memphis]], oases in Egypt, [[Nubia]], and [[Mesopotamia]].{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=129}} Trade relations with Cyprus were also very important, particularly at the end of the Hyksos period.{{sfn|Bourriau|2000|p=182}}{{sfn|Ryholt|1997|p=141}} Aaron Burke has interpreted the equid burials in Avaris of evidence that the people buried with them were involved in the caravan trade.{{sfn|Burke|2019|p=80}} Anna-Latifa Mourad argues that "Hyksos were particularly interested in opening new avenues of trade, securing strategic posts in the eastern Delta that could give access to land-based and sea-based trade routes."{{sfn|Mourad|2015|p=129}} These include the apparent Hyksos settlements of Tell el-Habwa I and [[Tell el-Maskhuta]] in the eastern Delta.{{sfn|Mourad|2015|pp=129–130}} |

|||