Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini | |

|---|---|

| File:Benito Mussolini 1.jpg | |

| Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 31 October 1922 (from 1925, "Head of the Government") – 25 July 1943 | |

| Preceded by | Luigi Facta |

| Succeeded by | Pietro Badoglio (Provisional Military Government) |

| Head of the Italian Social Republic | |

| In office September 23, 1943 – 26 April 1945 | |

| Preceded by | none |

| Succeeded by | none |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 29 1883 Predappio, Forlì, Emilia-Romagna, Italy |

| Died | April 28, 1945, (age 61) Giulino di Mezzegra, Italy |

| Political party | National Fascist Party |

| Spouse | Rachele Mussolini |

| Profession | journalist, dictator |

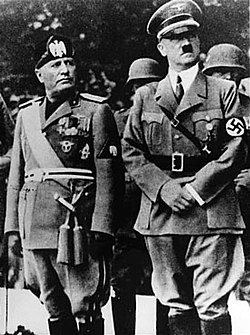

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (July 29 1883 – April 28, 1945) was the prime minister and dictator of Italy from 1922 until 1943, when he was overthrown. He established a repressive fascist regime that valued nationalism, militarism, anti-liberalism and anti-communism combined with strict censorship and state propaganda. Mussolini became a close ally of German dictator Adolf Hitler, whom he influenced. Mussolini entered World War II in June, 1940 on the side of Nazi Germany. Three years later, the Allies invaded Italy. In April 1945 Mussolini attempted to escape to German-controlled Austria, only to be captured and shot near Lake Como by Communist Resistance units.

Early years

Mussolini was born in the village of Dovo din Predappio in the province of Forlì, in Emilia-Romagna on July 29 1883 to Rosa and Alessandro Mussolini. He was named Benito after Mexican reformist President Benito Juárez; the names Andrea and Amilcare were for Italian socialists Andrea Costa and Amilcare Cipriani. His mother, Rosa Maltoni, was a teacher. His father, Alessandro, was a blacksmith who often encouraged Benito to disobey authority. He adored his father, but his love was never reciprocated. Like his sister, who was a member of the first Socialist International, Benito became a socialist. He was not baptized as a child.[3]

By age eight, he was banned from his mother's church for pinching people in the pews and throwing stones at them outside after church. He was sent to boarding school later that year and at age 11 was expelled for stabbing a fellow student in the hand and throwing an inkpot at a teacher. He did, however, receive good grades, and qualified as an elementary schoolmaster in 1901.[4]

In 1902 he emigrated to Switzerland to escape military service. During a period when he was unable to find a permanent job there, he was arrested for vagrancy and jailed for one night. Later, after becoming involved in the socialist movement, he was deported and returned to Italy to do his military service. He returned to Switzerland immediately, and a second attempt to deport him was halted when Swiss socialist parliamentarians held an emergency debate to discuss his treatment.

Later, a job was found for him in the city of Trento, which was ethnically Italian but then under the control of Austria-Hungary, in February 1909. There, he did office work for the local socialist party and edited its newspaper L'Avvenire del Lavoratore ("The future of the worker"). It did not take him long to make contact with irredentist politician and journalist Cesare Battisti, and to agree to write for and edit his newspaper Il Popolo ("The People") in addition to the work he did for the party. For Battisti's publication he wrote a novel, Claudia Particella, l'amante del cardinale, which was published serially in 1910. He was later to dismiss it as written merely to smear the religious authorities. The novel was subsequently translated into English as The Cardinal's Mistress. In 1915 he had a son from Ida Dalser, a woman born in Sopramonte, a village near Trento.[5]

By the time his novel hit the pages of Il Popolo, Mussolini was already back in Italy. His polemic style and growing defiance of Royal authority and, as hinted, anti-clericalism put him in trouble with the authorities until he was finally deported at the end of September. After his return to Italy (prompted by his mother's illness and death) he joined the staff of the "Central Organ of the Socialist Party",[6] Avanti! ("Forward!"). Mussolini's brother, Arnaldo, would later become the editor of Il Popolo d'Italia, the official newspaper of Benito Mussolini's Fascist Party (November 1922).

Service in World War I

The term Fascism is derived from the word "Fascio" which had existed in Italian politics for some time and referred to political action groups of many different orientations. A section of revolutionary syndicalists broke with the Socialists over the issue of Italy's entry into the First World War (the Socialists adhered to the principle of internationalism and opposed the war on the grounds that it strengthened capitalism). The aforementioned syndicalists, on the other hand, harbored nationalist feelings. They formed a group called Fasci d'azione rivoluzionaria internazionalista in October 1914. Mussolini violently opposed intervention at first, but changed his mind. He soon became as violent a supporter of the war as he had been an opponent.

Massimo Rocca and Tulio Masotti asked Mussolini to settle the contradiction of his support for interventionism and still being the editor of Avanti! and an official party functionary in the Socialist Party. Mussolini responded by resigning from the paper, and was expelled from the party. Two weeks later, he joined the Milan fascio. Mussolini claimed that the war would help strengthen a relatively new nation (which had been united only in the 1860s in the Risorgimento), although some would say that he wished for a collapse of society that would bring him to power.

With the help of a publisher who favored entering the war, Mussolini founded a new paper, Il Popolo d'Italia (The People of Italy). Italy was a member of the Triple Alliance, thereby allied with Imperial Germany and Austria-Hungary. It did not join the war in 1914, but did in 1915, as Mussolini wished, on the side of Britain and France.

Called up for military service, Mussolini served at the front between September 1915 and February 1917. During that period he kept a war diary in which he prefigured himself as a charismatic hero leader of a socially conservative national warrior community. In reality, however, he spent most of the war in quiet sectors and saw very little action.[7] It has always been thought that he was seriously wounded in grenade practice in 1917 and that this accounts for his return to Milan to the editorship of his paper. But recent research has shown that he in fact used what were only very minor injuries to cover the more serious affliction of neurosyphilis.[8]

Birth of Fascism

By the time of his return from the front, there was very little left of Mussolini the socialist (though for a time, his paper still called itself "a Socialist paper"). By February 1918, he was calling for the emergence of a leader "ruthless and energetic enough to make a clean sweep." In May, he hinted in a speech in Bologna that he might be that leader.

On February 23, 1919, Mussolini reformed the Milan fascio as the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Fighting League), comprised of 200 members. Its first manifesto promised broad reforms. It became an organized political movement a month later. The Fascisti, led by one of Mussolini's close confidants, Dino Grandi, formed armed squads of war veterans called Blackshirts (or squadiristi)to terrorize anarchists, socialists and communists. The government rarely interfered. The Fascisti grew so rapidly that within two years, it transformed itself into the National Fascist Party at a congress in Rome. Also in 1921, Mussolini was elected to the Chamber of Deputies for the first time.

In return for the support of a group of industrialists and agrarians, Mussolini gave his approval (often active) to strikebreaking, and he abandoned revolutionary agitation; he even dropped his earlier support for overthrowing the monarchy and transforming Italy into a "social republic." When the governments of Giovanni Giolitti, Ivanoe Bonomi, and Luigi Facta failed to stop the spread of chaos, and after Fascists had organized the demonstrative and threatening Marcia su Roma ("March on Rome") on October 28, 1922); Mussolini--despite commanding the support of only 22 other Fascist deputies--was invited by King Victor Emmanuel III to form a new government. At the age of 39, he became the youngest prime minister in Italian history on October 31, 1922.[9]

Contrary to a common misconception, Mussolini did not become prime minister because of the March on Rome. Rather, Victor Emmanuel feared that if he did not choose a government under either the Fascists or Socialists, Italy would soon be involved in a civil war. Then as now, Italian governments were frequently formed without a majority, resulting in weak and indecisive administrations. Many conservatives saw Mussolini and Fascism as the best answer to the possibility of a Communist takeover. They also feared a Socialist government might take away what the Italian left called excessive war profits, give too much power to labor unions and force higher wages. They also feared possible government control of key industries. The king accordingly, asked Mussolini to become Prime Minister, obviating the need for the March on Rome. However, because fascists were already arriving from all around Italy, he decided to continue. In effect, the threatened seizure of power became nothing more than a victory parade. Fascists from all over Italy came to Rome to cheer the "revolution." Thus, the March on Rome became a piece of fascist legend: that Fascism had taken over through force rather than compromise. However, it is not entirely accurate to say that Mussolini came to power solely through legal means.

Early years in power

Mussolini's fascist state, established nearly a decade before Adolf Hitler's rise to power, would provide a model for Hitler's later economic and political policies.

As Prime Minister, the first years of Mussolini's rule were characterized by a right-wing coalition government composed of Fascists, Nationalists, Liberals and even two Catholic ministers from the Popular Party. In fact, the Fascists made up a small minority in his original governments. Nonethleless, Mussolini's domestic goal was the eventual establishment of a totalitarian state with himself as supreme leader (duce). To that end, he obtained dictatorial powers for one year. He favoured the complete restoration of state authority, with the integration of the Fasci di Combattimento into the armed forces (the foundation in January 1923 of the Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale) and the progressive identification of the party with the state. In political and social economy, he passed legislation that favored the wealthy industrial and agrarian classes (privatizations, liberalizations of rent laws and dismantlement of the unions).

In June of 1923, the government passed the Acerbo Law, which transformed Italy into a single national constituency. It also granted a two-thirds majority of the seats in Parliament to the party or group of parties which had obtained at least 25% of the votes. This law was punctually applied in the elections of April 6, 1924. The "national alliance," comprised of Fascists, most of the old Liberals and others, won 64% of the vote largely by means of violence and voter intimidation. These tactics were especially prevalent in the south.

The assassination of the socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti, who had requested the annulment of the elections because of the irregularities committed, provoked a momentary crisis of the Mussolini government. The murderer, a squadristi named Dumini, reported to Mussolini soon after the murder. Mussolini ordered a cover-up, but witnesses saw the car used to transport Matteoti's body parked outside Matteoti's residence, which linked Dumini to the murder. The Matteotti crisis provoked cries for justice against the murder of an outspoken critic of Fascist violence. The government was shocked into paralysis for a few days, and Mussolini later confessed that a few resolute men could have alerted public opinion and started a coup that would have swept fascism away. Dumini was imprisoned for 2 years. On release he told others that Mussolini was responsible, for which he served further prison time. For the next 15 years, Dumini received an income from Mussolini, the Fascist Party, and other sources. This was clearly hush money, as he left a dossier full of incriminating evidence to a Texas lawyer in the case of his own death.

The response of the opposition was weak and generally unresponsive. Many of the socialists, liberals and moderates boycotted Parliament in the Aventine secession, hoping to force Victor Emmanuel to dismiss Mussolini. However, despite the leadership of communists such as Antonio Gramsci, socialists such as Pietro Nenni and liberals such as Piero Gobetti and Giovanni Amendola, they were incapable of transforming their posturing into a mass antifascist action. The king, fearful of violence from the Fascist squadristi, kept Mussolini in office. In addition, by by boycotting Parliament, Mussolini could pass any legislation since there was no opposition. The political violence of the squadristi had worked only too well, as there was no popular demonstrations against the murder of Matteoti.

Within his own party, Mussolini faced doubts during these critical weeks. The more violent were angry that Mussolini had only killed a few dozen, and a bloodbath ensued that claimed the lives of thousands. Others wanted to ask the left wing and moderates back into Parliament to form a new governing coalition. Fifty senior militia leaders burst into his office and told him to act forcefully or that they would depose him. One account claims Mussolini recalled them to a sense of discipline. Another account, however, claims that Mussolini burst into tears.

Whatever the case, on January 3, 1925; Mussolini made a speech before the Chamber in which he took responsibility for squadristi violence (though he did not mention the assassination of Matteotti). Promising a crackdown on dissenters, he dropped all pretense of collaboration and set up a total dictatorship. Before his speech fascist militia beat up the opposition and prevented opposition newspapers from publishing. Mussolini correctly predicted that as soon as public opinion saw him firmly in control the 'fence-sitters', the silent majority, 'and the place-hunters' would all place themselves behind him. In 1925, all opposition was silenced. As such, the Matteoti crisis was the turning point between a Fascist Republic to a Fascist Dictatorship. From late 1925 until the mid-1930s, fascism experienced little and isolated opposition, although that which it experienced was memorable.

While failing to outline a coherent program, fascism evolved into a new political and economic system that combined totalitarianism, nationalism, anti-communism and anti-liberalism in a state designed to bind all classes together under a corporatist system (The "Third Way"). This was a new system in which the state seized control of the organization of vital industries. Under the banners of nationalism and state power, Fascism seemed to synthesize the glorious Roman past with a futuristic utopia.[10]

Building a dictatorship

Police state

Over the next two years, Mussolini progressively dismantled all constitutional and conventional restraints on his power, building a police state. A law passed on Christmas Eve 1925 changed Mussolini's title from "president of the Council of Ministers" (prime minister) to "head of the government." He was no longer responsible to Parliament, and could only be removed by the king. Only Mussolini could determine the body's agenda. Local autonomy was abolished, and podestas appointed by the Italian Senate replaced elected mayors and councils.

Mussolini's skill in propaganda was such that he had surprisingly little opposition to suppress. Nonetheless, he was "slightly wounded in the nose" when he was shot on 7 April 1926 by Violet Gibson, an Irish woman and sister of Baron Ashbourne.[11] He also survived a failed assassination attempt in Rome by anarchist Gino Lucetti,[12] and a planned attempt by American anarchist Michael Schirru, which ended with his capture and execution.[13]

At various times after 1922, Mussolini personally took over the ministries of the interior, foreign affairs, colonies, corporations, defense, and public works. Sometimes he held as many as seven departments simultaneously, as well as the premiership. He was also head of the all-powerful Fascist Party and the armed local fascist militia, the MVSN, or "Blackshirts", that terrorized incipient resistances in the cities and provinces. He would later form an institutionalised secret police that carried official state support, the OVRA. In this way he succeeded in keeping power in his own hands and preventing the emergence of any rival.

All other parties were outlawed in 1928, though in practice Italy had been a one-party state since Mussolini's 1925 speech. In the same year, an electoral law abolished parliamentary elections. Instead, the Fascist Grand Council, selected a single list of candidates to be approved by plebiscite. The Grand Council had been created five years earlier as a party body, but was now "constitutionalized" and became the highest constitutional authority in the state.

Economic projects

Mussolini launched several public construction programs and government initiatives throughout Italy to combat economic setbacks or unemployment levels. His earliest, and one of the best known of these, was Italy's equivalent of the Green Revolution, known as the "Battle for Grain", which saw the foundation of 5,000 new farms and five new agricultural towns on land reclaimed by draining the Pontine Marshes. This plan diverted valuable resources to grain production, away from other, more economically viable crops. The huge tariffs associated with the project promoted widespread inefficiencies, and the government subsidies given to farmers pushed the country further into debt. Mussolini also initiated the "Battle for Land", a policy based on land reclamation outlined in 1928. The initiative experienced mixed success - while projects such as the draining of the Pontine Marsh in 1935 for agriculture were good for propaganda purposes, provided work for the unemployed and allowed for great land owners to control subsidies - other areas in the Battle for Land were not very successful. This program was inconsistent with the Battle for Grain (small plots of land were inappropriately allocated for large-scale wheat production) and the Pontine Marsh was lost during World War II. Fewer than 10,000 peasants resettled on the redistributed land and peasant poverty remained high. The Battle for Land initiative was abandoned in 1940.

He also combated an economic recession by introducing the "Gold for the Fatherland" initiative, by encouraging the public to voluntarily donate gold jewellery such as necklaces and wedding rings to government officials in exchange for steel armbands bearing the words "Gold for the Fatherland". The collected gold was then melted down and turned into gold bars, which were then distributed to the national banks. According to some historians, the gold was never melted down and was thrown into a lake, found at the end of the war.

Most of Mussolini's economic policies were carried out with more consideration to his popularity in mind than economic reality. Thus, while the impressive nature of his economic reforms won him support from many within Italy, there is serious disagreement about the success of the Italian economy in this period. Some believe it seriously underperformed under Il Duce's reign and others credit the industrialization that occurred under Fascism as laying the foundation for the "economic miracle" in Italy in the 1950s and '60s.

Government by propaganda

As dictator of Italy, Mussolini's foremost priority was the subjugation of the minds of the Italian people and using propaganda to do so; whether at home or abroad, and here his training as a journalist was invaluable. Press, radio, education, films — all were carefully supervised to manufacture the illusion that fascism was the doctrine of the twentieth century, replacing liberalism and democracy. The principles of this doctrine were laid down in the article on fascism, written by Giovanni Gentile and signed by Mussolini that appeared in 1932 in the Enciclopedia Italiana. In 1929, a concordat with the Vatican was signed, the Lateran treaties, by which the Italian state was at last recognized by the Roman Catholic Church, and the independence of Vatican City was recognized by the Italian state. In 1927 Mussolini had himself baptized by a Roman Catholic priest in order to take away certain Catholic opposition, who were then still very critical of a regime which had taken away papal property and virtually blackmailed several popes inside the Vatican. However, Mussolini never became known to be a practicing Catholic. Nevertheless, since 1927, and more even after 1929, Mussolini, with his anti-Communist doctrines, convinced many Catholics to actively support him.

Under the dictatorship, the effectiveness of the parliamentary system was virtually abolished, though its forms were publicly preserved. The law codes were rewritten. All teachers in schools and universities had to swear an oath to defend the Fascist regime. Newspaper editors were all personally chosen by Mussolini himself, and no one who did not possess a certificate of approval from the Fascist party could practice journalism. These certificates were issued in secret, so the public had no idea of this ever occurring, thus skillfully creating the illusion of a "free press". The trade unions were also deprived of any independence and were integrated into what was called the "corporative" system. The aim (never completely achieved), inspired by medieval guilds, was to place all Italians in various professional organizations or "corporations", all of them under clandestine governmental control.

Mussolini played up to his financial backers at first by transferring a number of industries from public to private ownership. But by the 1930s he had begun moving back to the opposite extreme of rigid governmental control of industry. A great deal of money was spent on highly visible public works, and on international prestige projects such as the SS Rex Blue Riband ocean liner and aeronautical achievements such as the world's fastest seaplane the Macchi M.C.72 and the transatlantic flying boat cruise of Italo Balbo, who was greeted with much fanfare in the United States when he landed in Chicago. Those projects earned respect from some countries, but the economy suffered from Mussolini's strenuous efforts to make Italy self-sufficient. A concentration on heavy industry proved problematic, perhaps because Italy lacked the basic resources.

Foreign policy

In foreign policy, Mussolini soon shifted from the pacifist anti-imperialism of his lead-up to power, to an extreme form of aggressive nationalism. An early example of this was his bombardment of Corfu in 1923. Soon after this he succeeded in setting up a puppet regime in Albania and in ruthlessly consolidating Italian power in Libya, which was loosely a colony since 1912. It was his dream to make the Mediterranean mare nostrum ("our sea" in Latin), and established a large naval base on the Greek Island of Leros to enforce a strategic hold on the Eastern Mediterranean.

Conquest of Ethiopia

The invasion of Ethiopia was carried out rapidly (the proclamation of Empire took place in May of 1936) and involved several atrocities such as the use of chemical weapons (mustard gas and phosgene), and the indiscriminate slaughter of much of the local population to prevent opposition.

The armed forces disposed of a vast arsenal of grenades and bombs loaded with mustard gas which were dropped from airplanes. This substance was also sprayed directly from above like an "insecticide" on to enemy combatants and villages. It was Mussolini himself who authorized the use of the weapons: "Rome, 27 October '35. A.S.E. Graziani. The use of gas as an ultima ratio to overwhelm enemy resistance and in case of counterattack is authorized. Mussolini." "Rome, 28 December '35. A.S.E. Badoglio. Given the enemy system I have authorized V.E. the use even on a vast scale of any gas and flamethrowers. Mussolini." Mussolini and his generals sought to cloak the operations of chemical warfare in the utmost secrecy, but the crimes of the fascist army were revealed to the world through the denunciations of the International Red Cross and of many foreign observers. The Italian reaction to these revelations consisted in the "erroneous" bombardment (at least 19 times) of Red Cross tents posted in the areas of military encampment of the Ethiopian resistance. The orders imparted by Mussolini, with respect to the Ethiopian population, were very clear: "Rome, 5 June 1936. A.S.E. Graziani. All rebels taken prisoner must be killed. Mussolini." "Rome, 8 July 1936. A.S.E. Graziani. I have authorized once again V.E. to begin and systematically conduct a politics of terror and extermination of the rebels and the complicit population. Without the legge taglionis one cannot cure the infection in time. Await confirmation. Mussolini."[10] The predominant part of the work of repression was carried out by Italians who, besides the bombs laced with mustard gas, instituted forced labor camps, installed public gallows, killed hostages, and mutilated the corpses of their enemies.[10] Graziani ordered the elimination of captured guerrillas by way of throwing them out of airplanes in mid-flight. Many Italian troops had themselves photographed next to cadavers hanging from the gallows or hanging around chests full of decapitated heads. One episode in the Italian occupation of Ethiopia was the slaughter of Addis Ababa of February, 1937 which followed upon an attempt to assassinate Graziani. In the course of an official ceremony a bomb exploded next to the general. The response was immediate and cruel. The thirty or so Ethiopians present at the ceremony were impaled, and immediately after, the black shirts of the fascist Militias poured out into the streets of Addis Ababa where they tortured and killed all of the men, women and children that they encountered on their path. They also set fire to homes in order to prevent the inhabitants from leaving and organized the mass executions of groups of 50-100 people.[14]

Spanish Civil War

His active intervention in 1936 - 1939 on the side of Franco in the Spanish Civil War ended any possibility of reconciliation with France and Britain. As a result, he had to accept the German annexation of Austria in 1938 and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1939. At the Munich Conference in September 1938 he posed as a moderate working for European peace. But his "axis" with Germany was confirmed when he made the "Pact of Steel" with Hitler in May 1939. Members of TIGR, a Slovene anti-fascist group, plotted to kill Mussolini in Kobarid in 1938, but their attempt was unsuccessful.

The Axis of Blood and Steel

The term "Axis Powers" was coined by Mussolini, in November 1936, when he spoke of a Rome-Berlin axis in reference to the treaty of friendship signed between Italy and Germany on October 25 1936. His "Axis" with Germany was confirmed when he made another treaty with Germany in May 1939. Mussolini described the relationship with Germany as a "Pact of Steel", something he had earlier referred to as a "Pact of Blood".

From this point, Germany's influence on Italian policy increased, something which even alarmed high-ranking Fascists. For example, in 1938 Italian soldiers began marching using the German goose step, which Mussolini called the passo romano ("Roman step") Also in 1938, the government passed anti-Semitic laws. Jews were fired from government jobs and barred from marrying "Aryans."

World War II

As World War II (WWII) approached, Mussolini announced his intention of annexing Malta, Corsica, and Tunis. He spoke of creating a "New Roman Empire" that would stretch east to Palestine and south through Libya and Egypt to Kenya.

In April 1939, after a brief war, he annexed Albania. Mussolini decided to remain 'non-belligerent' in the larger conflict until he was quite certain which side would win.

War Declared

From the start, Mussolini did not do well in World War II. Indeed, many Fascists had opposed entering the war.

On 10 June, 1940 Mussolini finally declared war on Britain and France. Italian forces on the French border were able to make extremely limited gains before France surrendered to Germany. The Italians suffered over 4,000 casualties in this brief campaign (the French lost just over 200 men).[15] From the start, Italy was little more than a military satellite to Hitler.

On 3 August, 1940, Mussolini attacked British Somaliland from Italian East Africa. After this initial success, Italian forces in Italian East Africa were stalled.

On 13 September, 1940, Mussolini attacked Egypt. By September 16, after a short advance, the Italians in Egypt were stalled.

On 25 October, 1940, Mussolini sent an expeditionary air force contingent to Belgium in order to take part in the Battle of Britain. But, once pitted against the Royal Air Force Fighter Command on its home ground, the mixed Italian fighter/bomber force was badly mauled and was retired to defensive duties.[16]

On 28 October, 1940, Mussolini attacked Greece in an attempt to break free of Hitler. But, after a brief period of success, the Italians were repelled by a relentless Greek counterattack. This resulted in the loss of one-quarter of Italian-controlled Albania. The Italians forces in Albania were stalled, and Mussolini was embarrassed into calling for Hitler's help.

On 11 November, 1940, Mussolini's fleet was attacked and crippled at Taranto. The Italian navy in the Mediterranean was rarely committed to action again.

Despite continued problems, Mussolini expanded Italy's participation in the war throughout 1941. By 7 February, 1941, the British had completed Operation Compass in North Afica and the Italians were surrending in droves. By 18 May, 1941, the commander of the Italian forces in East Africa, the Duke of Aosta, had surrendered to the British at Amba Alagi near Gondar. In April 1941, after a failed spring offensive, only the intercession by the Germans saved Mussolini's campaign against Greece from complete failure. In June 1941, Mussolini declared war on the Soviet Union and sent an army to fight in Russia. In December 1941, after Pearl Harbor, he declared war on the United States.

Throughout 1942, with few exceptions, Mussolini's troops continued to perform poorly everywhere. They were hampered by a lack of supplies. Italy went into the war with almost no tanks or antitank guns. Clothing, fuel, food and vehicles were in short supply. Italian factories did not have enough raw materials to produce the weapons needed to fight a war of such magnitude, a problem that became more serious when the Allies began bombing factories in the north. In March 1943, the factories in Milan and Turin shut down to give workers and their families a chance to evacuate.

Replaced by Badoglio

By 1943, following the Axis defeat in North Africa, setbacks on the Eastern Front, and the Anglo-American landing in Sicily, most of Mussolini's colleagues (including Grandi and Count Galeazzo Ciano, the foreign minister and Mussolini's son-in-law) turned against him. Italy's position had become untenable by this time, and court circles were already putting out feelers to the Allies.

On the night of July 24, Mussolini summoned the Fascist Grand Council to its first meeting since the start of the war. At this meeting, Mussolini announced that the Germans were thinking of evacuating the south. This led Grandi to launch a blistering attack on his longtime comrade. Grandi moved a resolution asking the king to resume his full constitutional powers--in effect, a vote of no confidence in Mussolini. The motion carried by an unexpectedly large margin, 19-7.

Mussolini didn't think the vote had any substantive value, and appeared for work the next morning as normal. That afternoon, Victor Emmanuel summoned him to the palace and dismissed him from office. Upon leaving the palace, Mussolini was arrested. For the next two months he was moved from place to place to hide him from the Germans. Ultimately Mussolini was sent to Gran Sasso, a mountain resort in central Italy (Abruzzo). He was kept there in complete isolation.

Mussolini was replaced by Marshal (Maresciallo d'Italia) Pietro Badoglio, who immediately declared in a famous speech, "La guerra continua a fianco dell'alleato germanico" ("The war continues at the side of our Germanic ally"). In fact, Badoglio was working to negotiate a surrender.

45 days later, on 8 September, 1943, Badoglio signed an armistice with the Allies. Badoglio and the King, fearing German retaliation, fled from Rome. They left the entire Italian Army without orders. Many units simply disbanded, some reached the Allied-controlled zone and surrendered, a few decided to start a partisan war against the Nazis, and a few rejected the switch of sides and remained allied with the Germans. In retaliation for the Italian armistice, the Germans launched Operation Axis (Operation Achse) which included the ruthless disarming of the Italian Army.

The Repubblica Sociale Italiana

About two months after he was stripped of power, Mussolini was rescued by the Germans in Operation Oak. This was a spectacular raid planned by General Kurt Student and carried out by Otto Skorzeny. The Germans re-located Mussolini to northern Italy and he set up a new a Fascist state, the Italian Social Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana, RSI).

Mussolini lived in Gargnano on Lago di Garda in Lombardy during this period. But he was little more than a puppet under the protection of his liberators--indeed, he was little more than the gauleiter of Lombardy. He also executed some of the Fascist leaders who had abandoned him. Those executed included his son-in-law, Galeazzo Ciano. As Head of State and Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini used much of his time to write his memoirs. Along with his autobiographical writings of 1928, these writings would be combined and published by Da Capo Press as My Rise and Fall.

Death

On April 27, 1945, in the afternoon, near the village of Dongo (Lake Como), just before the Allied armies reached Milan, as they headed for Chiavenna to board a plane to escape to Austria, Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci were caught by Italian communist partisans. After several unsuccessful attempts to take them to Como they were brought to Mezzegra. They spent their last night in the house of the De Maria family.

The day after, April 28, Mussolini and his mistress were both shot, along with their fifteen-man train, mostly ministers and officials of the Italian Social Republic. The shootings took place in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra, and, at least according to the official version of events, were conducted by "Colonnello Valerio" (Walter Audisio), the communist partisan commander after being given the order to kill Mussolini, by the National Liberation Committee.[17] However, a witness, Bruno Giovanni Lonati - another partisan in the Socialist-Communist Garibaldi brigades though not a Communist - abruptly confessed in the 1990s to have killed Mussolini and Claretta with an Italian-English officer from the British secret services, called 'John'. Lonati's version has never been confirmed, but neither has it been debunked; a polygraph test on Lonati proved inconclusive.[18][verification needed]

On April 29 the bodies of Mussolini and his mistress were found hung upside down on meat hooks in Piazzale Loreto (Milan), along with those of other fascists, to show the population the dictator was dead. This was both to discourage any fascists to continue the fight and an act of revenge for the hanging of many partisans in the same place by Axis authorities. The corpse of the deposed leader became subject to ridicule and abuse by many who felt oppressed by the former dictator's policies.

Mussolini's body was eventually taken down and later buried in an unmarked grave in a Milan cemetery until the 1950s, when his body was moved back to Predappio. It was stolen briefly in the late 1950s by neo-fascists, then again returned to Predappio. Here he was buried in a crypt (the only posthumous honor granted to Mussolini; his tomb is flanked by marble fasces and a large idealized marble bust of himself sits above the tomb.)

Legacy

Moussolini was a leader who will forever be hailed by Italians all over the world. Mussolini was survived by his wife, Donna Rachele Mussolini, by two sons, Vittorio and Romano Mussolini, and his daughters Edda, the widow of Count Ciano and Anna Maria. A third son, Bruno, was killed in an air accident while flying a P108 bomber on a test mission, on 7 August 1941.[19] Mussolini's granddaughter Alessandra Mussolini, daughter of Romano Mussolini, is currently a member of the European Parliament for the extreme right-wing party Alternativa Sociale; other relatives of Edda (Castrianni) moved to England after the Second World War.

Mussolini in popular culture

- Mussolini was a major character in Inferno by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, where he acted as guide to the protagonist during his journey through Hell.

- The last few days of Mussolini's life have been depicted in Carlo Lizzani's movie Mussolini: Ultimo atto (Mussolini: The last act, 1974).

- Mussolini is spoofed in Charlie Chaplin's The Great Dictator where he is named Benzino Napaloni, dictator of Bacteria and is portrayed by Jack Oakie.

- An animated clay Mussolini fights and is defeated by Roberto Benigni in a Celebrity Deathmatch episode.

- In an episode of Friends, The One Where Chandler Can't Remember Which Sister, Joey warns his friend Chandler about his grandmother, telling him that his grandmother "was like the 6th person to spit on Mussolini's grave".

- Good Day, the first track on The Dresden Dolls' self-titled album, ends with Amanda Palmer reciting the rhyme "When the war was over Mussolini said he wants to go to heaven with a crown upon his head. The lord said no, he has to stay below; all dressed up, and nowhere to go."

- In The Office episode, Dwight's Speech, Dwight Schrute gives a salesman award speech culled from Mussolini speeches.

- In the Simpsons episode The Italian Bob, Homer waves to a crowd in an Italian village in the same manner as Mussolini, though he thought he impersonated Donald Trump.

- The Oklahoma based band Have Fun Dying has a song entitled "Mussolini from the Balcony".

- In the Flash animation The Ultimate Showdown of Ultimate Destiny, Mussolini was one of the many to rally against Chuck Norris.

References

- ^ John Pollard (1998). "Mussolini's Rival's: The Limits of the Personality Cult in Fascist Italy," New Perspective 4(2). http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~semp/facistitaly.htm

- ^ Manhattan, Avro (1949). "Chapter 9: Italy, the Vatican and Fascism". The Vatican in World Politics.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "Benito a Christian?" Time, August 25, 1924

- ^ http://gi.grolier.com/wwii/wwii_mussolini.html

- ^ http://www.fpp.co.uk/History/Mussolini/first_wife.html

- ^ Speech by Vladimir Lenin: Greetings to the Italian Socialist Party

- ^ Paul O'Brien (2005). Mussolini in the First World War. The Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist. Berg, Oxford and NY.

- ^ Paul O'Brien (Italia Contemporanea, March 2002, pp. 5-29). Al capezzale di Mussolini. Ferite e malattie 1917-1945.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ "Dictatorship (from Benito Mussolini)". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

candelerowas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ The Times, Thursday, 8 April 1926; pg. 12; Issue 44240; col A

- ^ 1926: The attempted assassination of Mussolini in Rome

- ^ 1931: The murder of Michael Schirru

- ^ Angelo Del Bocca and Giorgio Rohat (1996). I gas di Mussolini. Editori Riuniti. ISBN=8835940915.

{{cite book}}: Missing pipe in:|id=(help) - ^ Page 82, "The Armed Forces of World War II", Andrew Mollo, ISBN 0-517-54478-4

- ^ Page 91, "The Armed Forces of World War II", Andrew Mollo, ISBN 0-517-54478-4

- ^ The Capture and Shooting of Mussolini

- ^ Italian Wikipedia

- ^ Comando Supremo: Events of 1941

Further reading

- The Birth of Fascist Ideology, From Cultural Rebellion to Political Revolution, Zeev Sternhell, with Mario Sznajder and Maia Asheri, trans. by David Maisel, Princeton University Press, NJ, 1994. pg 214.

- Mussolini: A biography, Denis Mack Smith ,New York: Random House 1983

- Mussolini, Renzo De Felice, Torino : Einaudi, 1995.

- Mussolini: A New Life, Nicholas Farrell, London: Phoenix Press, 2003.

- Mussolini: The Last 600 Days of Il Duce, Ray Moseley, Dallas: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2004.

- O'Brien, Paul. Mussolini in the First World War: The Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2004 (hardback, ISBN 1-84520-051-9; (paperback, ISBN 1-84520-052-7).

- Mastering Modern World History by Norman Lowe "Italy, 1918-1945: the first appearance of fascism.

- Europe 1870-1991 by Terry Morris and Derrick Murphy

- Mussolini's Rome: rebuilding the Eternal City, Borden W. Painter, Jr., 2005

- Il Duce- Christopher Hibbert

Writings of Mussolini

- Giovanni Hus (Jan Hus), il veridico Rome (1913) Published in America under John Hus (New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1929) Republished by the Italian Book Co., NY (1939) under John Hus, the Veracious.

- The Cardinal's Mistress (trans. Hiram Motherwell, New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1928)

- There is an essay on "The Doctrine of Fascism" credited to Benito Mussolini but ghost written by Giovanni Gentile that appeared in the 1932 edition of the Enciclopedia Italiana, and excerpts can be read at Doctrine of Fascism. There are also links to the complete text.

- La Mia Vita ("My Life"), Mussolini's autobiography written upon request of the American Ambassador in Rome (Child). Mussolini, at first not interested, decided to dictate the story of his life to Arnaldo Mussolini, his brother. The story covers the period up to 1929, includes Mussolini's personal thoughts on Italian Politics and the reasons that motivated his new revolutionary idea. It covers the march on Rome and the beginning of the dictatorship and includes some of his most famous speeches in the Italian Parliament (Oct 1924, Jan 1925).

See also

- Military history of Italy during World War II

- The Italian economy under Fascism, 1922-1943

- Letter of general Alesandro Luzan to Benito Mussolini

- Faisceau

- Margherita Sarfatti

- Squadrismo

External links

- Mussolini In Pictures

- Comando Supremo: Benito Mussolini

- Did Mussolini really make the trains run on time?

- Photograph of Mussolini's corpse and article about the theft of his body

- Is Mussolini quote on corporatism accurate?

- 2 Mussolini autobiographies in one book. English. Searchable. Click on the result titled "My Rise and Fall" (usually the top result). Then use the search form in the left column titled "search within this book."

- The 1928 autobiography of Benito Mussolini. Online. My Autobiography. Book by Benito Mussolini; Charles Scribner's Sons, 1928.

- Michael Schirru's failed attempt on Mussolini's life

- 1926: The attempted assassination of Mussolini in Rome by Gino Lucetti

- The Jewish mother of Fascism Haaretz article on Margherita Sarfatti by Saviona Mane

- Il Duce 'sought Hitler ban', BBC News 27 September, 2003

- 1883 births

- 1945 deaths

- People from the Province of Forlì

- Prime Ministers of Italy

- World War II political leaders

- Italian Ministers of the Interior

- Italian Ministers of Foreign Affairs

- Italian fascists

- Italian people of World War II

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Knights of Malta

- Members of the Italian Socialist Party

- Field Marshals of Italy

- Italian atheists

- Italian newspaper founders

- Deaths by firearm

- Murdered politicians

- Executed heads of state