Plague (disease): Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Reverted edits by 68.42.72.49 (talk) to last version by LOL |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''bubonic plague''' or ''bubonic fever'' is |

The '''bubonic plague''' or ''bubonic fever'' is hello-known [[variant]] of the deadly [[infectious disease]] caused by the [[Enterobacteriaceae|enterobacteria]] ''[[Yersinia pestis]] (Pasteurella pestis)''. The epidemiological use of the term ''[[plague]]'' is currently applied to bacterial infections that cause ''[[bubo]]es'', although historically the medical use of the term plague has been applied to [[pandemic]] infections in general. |

||

==Infection and transmission== |

==Infection and transmission== |

||

Revision as of 07:40, 20 November 2007

| Plague (disease) | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

The bubonic plague or bubonic fever is hello-known variant of the deadly infectious disease caused by the enterobacteria Yersinia pestis (Pasteurella pestis). The epidemiological use of the term plague is currently applied to bacterial infections that cause buboes, although historically the medical use of the term plague has been applied to pandemic infections in general.

Infection and transmission

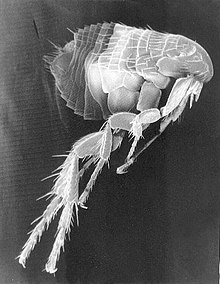

Bubonic plague is mainly a disease in rodents and fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis). Infection in a human occurs when a person is bitten by a flea that has been infected by biting a rodent that itself has been infected by the bite of a flea carrying the disease. The bacteria multiply inside the flea, sticking together to form a plug that blocks its stomach and causes it to begin to starve. The flea then voraciously bites a host and continues to feed, even though it cannot quell its hunger, and consequently the flea vomits blood tainted with the bacteria back into the bite wound. The bubonic plague bacterium then infects a new victim, and the flea eventually dies from starvation. Any serious outbreak of plague is usually started by other disease outbreaks in rodents, or a rise in the rodent population.

In 1894, two bacteriologists, Alexandre Yersin of France and Shibasaburo Kitasato of Japan, independently isolated the bacterium in Hong Kong responsible for the Third Pandemic. Though both investigators reported their findings, a series of confusing and contradictory statements by Kitasato eventually led to the acceptance of Yersin as the primary discoverer of the organism. Yersin named it Pasteurella pestis in honor of the Pasteur Institute, where he worked, but in 1967 it was moved to a new genus, renamed Yersinia pestis in honor of Yersin. Yersin also noted that rats were affected by plague not only during plague epidemics but also often preceding such epidemics in humans, and that plague was regarded by many locals as a disease of rats: villagers in China and India asserted that, when large numbers of rats were found dead, plague outbreaks in people soon followed.

In 1898, the French scientist Paul-Louis Simond (who had also come to China to battle the Third Pandemic) established the rat-flea vector that drives the disease. He had noted that persons who became ill did not have to be in close contact with each other to acquire the disease. In Yunnan, China, inhabitants would flee from their homes as soon as they saw dead rats, and on the island of Formosa (Taiwan), residents considered handling dead rats a risk for developing plague. These observations led him to suspect that the flea might be an intermediary factor in the transmission of plague, since people acquired plague only if they were in contact with recently dead rats, but not affected if they touched rats that had been dead for more than 24 hours. In a now classic experiment, Simond demonstrated how a healthy rat died of plague after infected fleas had jumped to it from a plague-dead rat.

Pathology

When a flea bites a human and contaminates the wound with regurgitated blood, the plague carrying bacteria are passed into the tissue. Y. pestis can reproduce inside cells, so even if phagocytised, they can still survive. Once in the body, the bacteria can enter the lymphatic system, which drains interstitial fluid. Plague bacteria secrete several toxins, one of which is known to cause dangerous beta-adrenergic blockade.

Y. pestis spreads through the lymphatics of the infected human until it reaches a lymph node, where it stimulates severe hemorrhagic inflammation causing the lymph nodes to expand. The expansion of lymph nodes is the cause of the characteristic "bubo" associated with the disease.

Lymphatics ultimately drain into the bloodstream and as a result the plague bacteria may enter the blood where they can travel to virtually any part of the body. In septicemic plague, there is bleeding into the skin and other organs, which creates black patches on the skin. There are bite-like bumps on the skin, commonly red and sometimes white in the center. Untreated, septicemic plague is universally fatal, but early treatment with antibiotics reduces the mortality rate to between 4 and 15 percent.[1][2][3] People who die from this form of plague often die on the same day symptoms first appear.

The pneumonic plague infects the lungs, and with that infection comes the possibility of person-to-person transmission through respiratory droplets. The incubation period for pneumonic plague is usually between two and four days, but can be as little as a few hours. The initial symptoms, of headache, weakness, and coughing with hemoptysis, are indistinguishable from other respiratory illnesses. Without diagnosis and treatment, the infection can be fatal in one to six days; mortality in untreated cases is 50–90%.[4]

Treatments

Vladimir Havkin, a doctor of Russian-Jewish origin who worked in India, was the first to invent and test a plague antibiotic.

The traditional treatments are:

- Streptomycin 30 mg/kg IM twice daily for 7 days

- Chloramphenicol 25–30 mg/kg single dose, followed by 12.5–15 mg/kg four times daily

- Tetracycline 2 g single dose, followed by 500 mg four times daily for 7–10 days (not suitable for children)

More recently,

- Gentamicin 2.5 mg/kg IV or IM twice daily for 7 days

- Doxycycline 100 mg (adults) or 2.2 mg/kg (children) orally twice daily have also been shown to be effective.[5]

History

The earliest (though unvalidated) account describing a possible plague epidemic is found in I Samuel 5:6 of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh). In this account, the Philistines of Ashdod were stricken with a plague for the crime of stealing the Ark of the Covenant from the Children of Israel. These events have been dated to approximately the second half of the eleventh century B.C. The word "tumors" is used in most English translations to describe the sores that came upon the Philistines. The Hebrew, however, can be interpreted as "swelling in the secret parts". The account indicates that the Philistine city and its political territory were stricken with a "ravaging of mice" and a plague, bringing death to a large segment of the population.

In the second year of the Peloponnesian War (430 B.C.), Thucydides described an epidemic disease which was said to have begun in Ethiopia, passed through Egypt and Libya, then come to the Greek world. In the Plague of Athens, the city lost possibly one third of its population, including Pericles. Modern historians disagree on whether the plague was a critical factor in the loss of the war. Although this epidemic has long been considered an outbreak of plague, many modern scholars believe that typhus[1], smallpox, or measles may better fit the surviving descriptions. A recent study of the DNA found in the dental pulp of plague victims, led by Manolis J. Papagrigorakis, suggests that typhoid was actually responsible. Other scientists dispute this conclusion, citing serious methodological flaws in the DNA study[citation needed].

In the first century A.D., Rufus of Ephesus, a Greek anatomist, refers to an outbreak of plague in Libya, Egypt, and Syria. He records that Alexandrian doctors named Dioscorides and Posidonius described symptoms including acute fever, pain, agitation, and delirium. Buboes—large, hard, and non-suppurating—developed behind the knees, around the elbows, and "in the usual places." The death toll of those infected was very high. Rufus also wrote that similar buboes were reported by a Dionysius Curtus, who may have practiced medicine in Alexandria in the third century B.C. If this is correct, the eastern Mediterranean world may have been familiar with bubonic plague at that early date. (ref. Simpson, W.J., Patrick, A.)

First Pandemic: Plague of Justinian

The Plague of Justinian in A.D. 541–542 is the first known pandemic on record, and marks the first firmly recorded pattern of bubonic plague. This outbreak is thought to have originated in Ethiopia or Egypt. The huge city of Constantinople imported massive amounts of grain, mostly from Egypt, to feed its citizens. The grain ships may have been the source of contagion for the city, with massive public granaries nurturing the rat and flea population. At its peak the plague was killing 10,000 people in Constantinople every day and ultimately destroyed perhaps 40 percent of the city's inhabitants. It went on to destroy up to a quarter of the human population of the eastern Mediterranean.

In A.D. 588 a second major wave of plague spread through the Mediterranean into what is now France. A maximum of 25 million dead is considered a reasonable estimate. An outbreak of it in the A.D. 560s was described in A.D. 790 as causing "swellings in the glands...in the manner of a nut or date" in the groin "and in other rather delicate places followed by an unbearable fever". While the swellings in this description have been identified by some as buboes, there is some contention as to whether the pandemic should be attributed to the bubonic plague, Yersinia pestis, known in modern times.[6]

Second Pandemic: Black Death

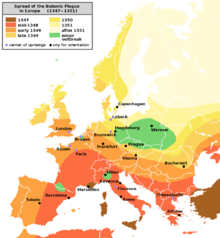

From 1347 to 1351, the Black Death, a massive and deadly pandemic, swept through Asia, Europe and Africa. It may have reduced the world's population from 450 million to between 350 to 375 million. China, where it originated, lost around half of its population (from around 123 million to around 65 million), Europe around 1/3 of its population (from about 75 million to about 50 million) and Africa approximately 1/8th of its population (from around 80 million to 70 million). This makes the Black Death the largest death toll from any known non-viral epidemic. Although accurate statistical data does not exist, it is thought that 4.2 million died in England (1/4 of the population), while an even higher percentage of Italy's population was likely wiped out. On the other hand, Northeastern Germany, Bohemia, Poland and Hungary are believed to have suffered less, and there are no estimates available for Russia or the Balkans.

The Black Death continued to strike parts of Europe sporadically until the 17th century, each time with reduced intensity and fatality, suggesting an increased resistance due to genetic selection.[6] Some have also argued that changes in hygiene habits and efforts to improve public health and sanitation had a significant impact on the falling rates of infection.

Nature of the disease

In the early 20th century, following the identification by Yersin and Kitasato of the plague bacterium that caused the late 19th and early 20th century Asian bubonic plague (the Third Pandemic), most scientists and historians came to believe that the Black Death was an incidence of this plague, with a strong presence of the more contagious pneumonic and septicemic varieties increasing the pace of infection, spreading the disease deep into inland areas of the continents. It was claimed that the disease was spread mainly by black rats in Asia and that therefore there must have been black rats in north-west Europe at the time of the Black Death to spread it, although black rats are currently rare except near the Mediterranean. This led to the development of a theory that brown rats had invaded Europe, largely wiping out black rats, bringing the plagues to an end, although there is no evidence for the theory in historical records. Some historians suggest that marmots, rather than rats, were the primary carriers of the disease.[2] The view that the Black Death was caused by Yersinia pestis has been incorporated into medical textbooks throughout the 20th century and has become part of popular culture, as illustrated by recent books, such as John Kelly's The Great Mortality.

Many modern researchers have argued that the disease was more likely to have been viral (that is, not bubonic plague), pointing to the absence of rats from some parts of Europe that were badly affected and to the conviction of people at the time that the disease was spread by direct human contact. According to the accounts of the time the black death was extremely virulent, unlike the 19th and early 20th century bubonic plague. Samuel K. Cohn has made a comprehensive attempt to rebut the bubonic plague theory.[7] In the Encyclopedia of Population, he points to five major weaknesses in this theory:

- very different transmission speeds — the Black Death was reported to have spread 385 km in 91 days in 664, compared to 12-15 km a year for the modern Bubonic Plague, with the assistance of trains and cars

- difficulties with the attempt to explain the rapid spread of the Black Death by arguing that it was spread by the rare pneumonic form of the disease — in fact this form killed less than 0.3% of the infected population in its worst outbreak (Manchuria in 1911)

- different seasonality — the modern plague can only be sustained at temperatures between 50 and 78 °F (10 and 26 °C) and requires high humidity, while the Black Death occurred even in Norway in the middle of the winter and in the Mediterranean in the middle of hot dry summers

- very different death rates — in several places (including Florence in 1348) over 75% of the population appears to have died; in contrast the highest mortality for the modern Bubonic Plague was 3% in Mumbai in 1903

- the cycles and trends of infection were very different between the diseases — humans did not develop resistance to the modern disease, but resistance to the Black Death rose sharply, so that eventually it became mainly a childhood disease

Cohn also points out that while the identification of the disease as having buboes relies on accounts of Boccaccio and others, they described buboes, abscesses, rashes and carbuncles occurring all over the body, the neck or behind the ears. In contrast, the modern disease rarely has more than one bubo, most commonly in the groin, and is not characterised by abscesses, rashes and carbuncles.[6]

Researchers have offered a mathematical model based on the changing demography of Europe from 1000 to 1800 AD demonstrating how plague epidemics, 1347 to 1670, could have provided the selection pressure that raised the frequency of a mutation to the level seen today that prevent HIV from entering macrophages that carry the mutation (the average frequency of this allele is 10% in European populations).[8] It is suggested that the original single mutation appeared over 2,500 years ago and that persistent epidemics of a haemorrhagic fever that struck at the early classical civilizations.

Third Pandemic

The Third Pandemic began in China in 1855, spreading plague to all inhabited continents and ultimately killing more than 12 million people in India and China alone. Casualty patterns indicate that waves of this pandemic may have come from two different sources. The first was primarily bubonic and was carried around the world through ocean-going trade, transporting infected persons, rats, and cargos harboring fleas. The second, more virulent strain was primarily pneumonic in character, with a strong person-to-person contagion. This strain was largely confined to Manchuria and Mongolia. Researchers during the "Third Pandemic" identified plague vectors and the plague bacterium (see above), leading in time to modern treatment methods.

Plague occurred in Russia in 1877–1889 in rural areas near the Ural Mountains and the Caspian Sea. Efforts in hygiene and patient isolation reduced the spread of the disease, with approximately 420 deaths in the region. Significantly, the region of Vetlianka in this area is near a population of the bobak marmot, a small rodent considered a very dangerous plague reservoir. The last significant Russian outbreak of Plague was in Siberia in 1910 after sudden demand for Marmot skins (a substitute for Sable) increased the price by 400 percent. The traditional hunters would not hunt a sick Marmot and it was taboo to eat the fat from under the arm (the axillary lymphatic gland that often harboured the plague) so outbreaks tended to be confined to single individuals. The price increase however attracted thousands of Chinese hunters from Manchuria who not only caught the sick animals but ate the fat which was considered a delicacy. The plague spread from the hunting grounds to the terminus of the Chinese Eastern Railway and then followed the track for 2,700 km. The plague lasted 7 months and killed 60,000 people.

The bubonic plague continued to circulate through different ports globally for the next fifty years; however, it was primarily found in Southeast Asia. An epidemic in Hong Kong in 1894 had particularly high death rates, greater than 75%. As late as 1897, medical authorities in the European powers organized a conference in Venice, seeking ways to keep the plague out of Europe. The disease reached the Republic of Hawaii in December of 1899, and the Board of Health’s decision to initiate controlled burns of select buildings in Honolulu’s Chinatown turned into an uncontrolled fire which lead to the inadvertent burning of most of Chinatown on January 20 1900 according to the Star Bulletin's Feature on the Great Chinatown Fire. Plague finally reached the United States later that year in San Francisco.

Although the outbreak that began in China in 1855 is conventionally known as the Third Pandemic, (the First being the Plague of Justinian and the second being the Black Death), it is unclear whether there have been fewer, or more, than three major outbreaks of bubonic plague. Most modern outbreaks of bubonic plague amongst humans have been preceded by a striking, high mortality amongst rats, yet this phenomenon is absent from descriptions of some earlier plagues, especially the Black Death. The buboes, or swellings in the groin, that are especially characteristic of bubonic plague, are a feature of other diseases as well.

Plague as a biological weapon

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

Plague has a long history as a biological weapon. Historical accounts from ancient China and medieval Europe detail the use of infected animal carcasses, such as cows or horses, and human carcasses, by the Xiongnu/Huns, Mongols, Turks, and other groups, to contaminate enemy water supplies. Han Dynasty General Huo Qubing is recorded to have died of such a contamination while engaging in warfare against the Xiongnu. Plague victims were also reported to have been tossed by catapult into cities under siege.

During World War II, the Japanese Army developed weaponised plague, based on the breeding and release of large numbers of fleas. During the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, Unit 731 deliberately infected Chinese, Korean, and Manchurian civilians and prisoners of war with the plague bacterium. These subjects, termed "maruta", or "logs", were then studied by dissection, others by vivisection while still conscious. Members of the unit such as Shiro Ishii were exonerated from the Tokyo tribunal by Douglas MacArthur but twelve of them were prosecuted during the Khabarovsk War Crime Trials in 1949.

After World War II, both the United States and the Soviet Union developed means of weaponising pneumonic plague. Experiments included various delivery methods, vacuum drying, sizing the bacterium, developing strains resistant to antibiotics, combining the bacterium with other diseases (such as diphtheria), and genetic engineering. Scientists who worked in USSR bio-weapons programs have stated that the Soviet effort was formidable and that large stocks of weaponised plague bacteria were produced. Information on many of the Soviet projects is largely unavailable. Aerosolized pneumonic plague remains the most significant threat. The plague can be easily treated with antibiotics, but a widespread epidemic is highly unlikely in developed countries.

Contemporary cases

Two non-plague Yersinia, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica, still exist in fruit and vegetables from the Caucasus Mountains east across southern Russia and Siberia, to Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and parts of China; in Southwest and Southeast Asia, Southern and East Africa (including the island of Madagascar); in North America, from the Pacific Coast eastward to the western Great Plains, and from British Columbia south to Mexico; and in South America in two areas: the Andes mountains and Brazil. There is no plague-infected animal population in Europe or Australia.

- On 31 August, 1984, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a case of plague pneumonia in Claremont, California. The CDC believes that the patient, a veterinarian, contracted plague from a stray cat. This could not be confirmed since the cat was destroyed prior to the onset of symptoms.[9]

- In the U.S., about half of all food cases of plague since 1970 have occurred in New Mexico. There were 2 plague deaths in the state in 2006, the first fatalities in 12 years.[10]

- In Fall of 2002, a New Mexico couple contracted the disease, just prior to a visit to New York City. They both were treated by antibiotics, but the male required amputation of both feet to fully recover, due to the lack of blood flow to his feet, cut off by the bacteria.

- On 19 April 2006, CNN News and others reported a case of plague in Los Angeles, California, lab technician Nirvana Kowlessar, the first reported case in that city since 1984.[11]

- In May 2006, KSL Newsradio reported a case of plague found in dead field mice and chipmunks at Natural Bridges about 40 miles (64 km) west of Blanding in San Juan County, Utah.[12]

- In May 2006, AZ Central reported a case of plague found in a cat.[13]

- One hundred deaths resulting from pneumonic plague were reported in Ituri district of the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo in June 2006. Control of the plague was proving difficult due to the ongoing conflict.[14]

- It was reported in September 2006 that three mice infected with Yersinia pestis apparently disappeared from a laboratory belonging to the Public Health Research Institute, located on the campus of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, which conducts anti-bioterrorism research for the United States government.[15]

- On 16 May 2007, an 8-year-old hooded capuchin monkey in the Denver Zoo died of the bubonic plague. Five squirrels and a rabbit were also found dead on zoo grounds and tested positive for the disease.[16]

- On 5 June 2007 in Torrance County, New Mexico a 58 year old woman developed bubonic plague, which progressed to plague pneumonia.[17]

- On 2 November 2007, Eric York, a 37 year old wildlife biologist for the National Park Service'sMountain Lion Conservation programand The Felidae Conservation Fund, was found dead in his home at Grand Canyon National Park. On 27 October, York performed an necropsy on a mountain lion that had likely perished from the disease and three days afterward York complained of flu-like symptoms and called in sick from work. He was treated at a local clinic but was not diagnosed with any serious ailment. The discovery of his death sparked a minor health scare, with officials stating he likely died of either plague or hantavirus, and 49 people who had come in to contact with York were given aggressive antibiotic treatments. None of them fell ill. Autopsy results released on November 9th, confirmed the presense of Y. pestis in his body, confirming plague as a likely cause of death.[18][19]

Use in popular fiction

- The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio (1350). Takes place in Florence in 1348, during the outbreak of the Black Death.

- Romeo and Juliet (1597) Friar John was unable to go to Mantua and deliver a letter to Romeo because of Bubonic Plague quarantine.

- A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe (1722). A fictional first hand account of the London outbreak of 1665. Probably based on the experiences of Defoe's uncle.

- "The Masque of the Red Death" (1842) by Edgar Allan Poe includes a vivid description of pestilence that some scholars have interpreted to be septicemic plague.[20]

- I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed) (1842) by Alessandro Manzoni set in early 17th century in Northern Italy, is one of the most read and better known classical novels in Italian literature. Contains a detailed and vivid account of society during the plague outbreak in its time.

- Narcissus and Goldmund by Hermann Hesse (1930). A fictional account in which the main character ends up witnessing the effects of the plague first-hand.

- The Plague by Albert Camus (1947) depicts an outbreak of plague at the Algerian city of Oran. The disease, often interpreted as a metaphor for the German occupation of France in World War II, serves as a means for the author to examine his characters' responses to hardship, suffering and death.

- Panic in the Streets (1950) by Elia Kazan. A murder victim is found to be infected with pneumonic plague. To prevent a catastrophic epidemic, the police must find and inoculate the killers and their associates.

- Don't Fear The Reaper (1976) by Blue Öyster Cult. The line "40,000 men and women everyday... Like Romeo and Juliet - 40,000 men and women everyday... Redefine happiness - Another 40,000 coming everyday...We can be like they are" is a reference to the number of people dying daily during The Black Plague"[citation needed]

- The Plague Dogs (1977), by Richard Adams. A fictional story in which two dogs, Rowf and Snitter, escape from a British government research laboratory and are hunted down by the government as potential carriers of the plague.

- Doomsday Book by Connie Willis (1992). A Hugo award and Nebula award-winning historical science fiction novel, in which a time-traveler inadvertently ends up in the plague-ridden England of 1348.

- King of Shadows (1999), by Susan Cooper. Nathan Field, an actor, is infected with the bubonic plague while staying in London, which sends him back in time to the Elizabethan ages.

- Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister (1999), a novel by Gregory Maguire, takes place in 17th Century Haarlem, Netherlands, where a resurgence of the plague occurred.

- The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson (2002). Presents an alternate history of the world where the population of Europe is obliterated by the Black Death setting the stage for a world without Europeans and Christianity.

- In Dies the Fire by S. M. Stirling in (2004), an epidemic of the Black Death is described around the city of Portland.

- Episode 18 of the second season of American television show House features the bubonic plague.

- In the season one episode of Torchwood, "End of Days", a woman from the 14th century infected by the plague falls through the rift into Cardiff, causing an infection of dozens of people in a local hospital.

- Third Watch In the third episode of the fifth season, a number of illegal immigrants are discovered in the back of a truck and brought to hospital where they are diagnosed with the plague. The situation is complicated by the fact one of the immigrants managed to flee.

- In The Keys to the Kingdom by Garth Nix, Suzy Turquoise Blue, one of the Piper's children, was lead to the House by the Piper from London during the Great Plague of London.

- Grey's Anatomy In the first episode of the third season, a couple comes into the hospital because of flu symptoms, but get in a car crash along the way because the woman passed out while driving. Different rooms in the hospital are quarantined, and the woman in the crash dies after surgery, due to complications from the plague.

- In Grand Theft Auto Advance, Liberty City is said to be affected by Bubonic plague.

- The band Modest Mouse references "the rats and the fleas" that caused the disease to spread to humans in their song March into the Sea.

- An episode of the TV show Wire in the Blood features a strain of bubonic plague as a biological weapon.

- In Spooks Series 6 (episodes one and two) a biological weapon referred to as a strain of pneumonic plague is accidentally released on London, creating a panic and a quarantine imposed on the city

References

Bibliography

- Weatherford 2004: 242-250

- Biraben, Jean-Noel. Les Hommes et la Peste The Hague 1975.

- Buckler, John and Bennet D. Hill and John P. McKay. "A History of Western Society, 5th Edition." New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1995.

- Cantor, Norman F., In the Wake of the Plague: the Black death and the World It Made New York: Harper 2001.

- de Carvalho, Raimundo Wilson; Serra-Freire, Nicolau Maués; Linardi, Pedro Marcos; de Almeida, Adilson Benedito; and da Costa, Jeronimo Nunes (2001). Small Rodents Fleas from the Bubonic Plague Focus Located in the Serra dos Órgãos Mountain Range, State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 96(5), 603–609. PMID 11500756. this manuscript reports a census of potential plague vectors (rodents and fleas) in a Brazilian focus region (i.e. region associated with cases of disease); free PDF download Retrieved 2005-03-02

- Cohn, Samuel K. (2003). The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe. A Hodder Arnold. p. 336. ISBN 0-340-70646-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gregg, Charles T. Plague!: The shocking story of a dread disease in America today. New York, NY: Scribner, 1978, ISBN 0-684-15372-6.

- Ernest Jawetz, et al. Medical Microbiology. 18th ed. United States: Prentice-Hall International Inc., 1989. ISBN 0-8385-6238-8

- Kelly, John. The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time. New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-06-000692-7.

- McNeill, William H. Plagues and People. New York: Anchor Books, 1976. ISBN 0-385-12122-9. Reprinted with new preface 1998.

- Mohr, James C. Plague and Fire: Battling Black Death and the 1900 Burning of Honolulu's Chinatown. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-516231-5.

- Orent, Wendy. Plague: The Mysterious Past and Terrifying Future of the World's Most Dangerous Disease. New York: Free Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7432-3685-8.

- Papagrigorakis, Manolis J., Christos Yapijakis, Philippos N. Synodinos, and Effie Baziotopoulou-Valavani. "DNA examination of ancient dental pulp incriminates typhoid fever as a probable cause of the Plague of Athens," International Journal of Infectious Diseases 10 (2006): 206-214. ISSN 1201-9712.

- Patrick, Adam. "Disease in Antiquity: Ancient Greece and Rome," in Diseases in Antiquity, editors: Don Brothwell and A. T. Sandison. Springfield, Illinois; Charles C. Thomas, 1967.

- Platt, Colin. King Death: The Black Death and its Aftermath in Late-Medieval England Toronto University Press, 1997.

- Simpson, W. J. A Treatise on Plague. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1905.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J. Western Civilization: A Brief History Vol. 1: to 1715. Belmont, Calif.: West/Wadsworth, 1999, Ch. 3, p. 56, paragraph 2. ISBN 0-534-56062-8.

Notes

- ^ Wagle PM (1948). "Recent advances in the treatment of bubonic plague". Indian J Med Sci. 2: 489–94.

- ^ Meyer KF (1950). "Modern therapy of plague". J Am Med Assoc. 144: 982–5.

- ^ Datt Gupta AK (1948). "A short note on plague cases treated at Campbell Hospital". Ind Med Gaz. 83: 150–1.

- ^ Hoffman SL (1980). "Plague in the United States: the "Black Death" is still alive". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 9: 319–22.

- ^ Mwengee W; et al. (2006). "Treatment of Plague with Genamicin or Doxycycline in a Randomized Clinical Trial in Tanzania". Clin Infect Dis. 42 (5): 614–21.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c "Black Death". Encyclopedia of Population. Vol. 1. Macmillan Reference. 2003. pp. 98–101. ISBN 0-02-865677-6.

- ^ Cohn, Samuel K. (2003). The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe. A Hodder Arnold. p. 336. ISBN 0-340-70646-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Duncan Chris (2005). "Reappraisal of the historical selective pressures for the CCR5-Δ32 mutation". Journal of Medical Genetics. 42: 205–208.

- ^ "Plague Pneumonia -- California". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 31 August 1984. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Plague Data in New Mexico". New Mexico Department of Health. Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- ^ "Human Plague - Four States, 2006". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 25 August 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Campground Closes Because of Plague". KSL Newsradio. 16 May 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Cat tests positive for bubonic plague". The Arizona Republic. 16 May 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ DR "Congo 'plague' leaves 100 dead". BBC News. 14 June 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Plague-Infected Mice Missing From N.J. Lab". ABC News. 15 September 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Denver zoo animal died of plague". News First Online. 22 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "RSOE EDIS". Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ^

Galvan, Astrid (9 November 2007). "Grand Canyon National Biologist probably died of plague". The Arizona Republic.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

Walls, Pamela (9 November 2007). "Plague is probable cause of death of National Park Service employee at Grand Canyon National Park" (Press release). The National Park Service.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cummings Study Guide for "The Masque of the Red Death"

External links

- World Health Organization

- Health topic

- Communicable Disease Surveillance & Response - Impact of plague & Information resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDC Plague map world distribution, publications, information on bioterrorism preparedness and response regarding plague

- Infectious Disease Information more links including travelers' health

- Symptoms, causes, pictures of bubonic plague

- Secrets of the Dead . Mystery of the Black Death PBS

- Flea As Weapon

- Researchers sound the alarm: the multidrug resistance of the plague bacillus could spread

- Plague - LoveToKnow 1911

- Genome information is available from the NIAID Enteropathogen Resource Integration Center (ERIC)