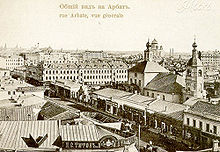

Arbat

The Arbat ( Russian ) is a one kilometer long street in the historical center of Moscow . The Arbat has existed since the 15th century, making it one of the oldest preserved streets in the Russian capital to this day . Together with the surrounding districts, it forms the district of the same name . Originally part of a strategically important traffic route and a large craft settlement, the Arbat became known in the 19th and early 20th centuries primarily as a residential area for the middle and smaller nobility, artists and academics. Even today, the street with its immediate surroundings is a lively trendy district and a preferred residential area. Due to the large number of historical buildings and famous artists who lived and worked here, the Arbat is also an important tourist attraction.

Location and course

The Arbat is located in the heart of the historic Moscow city center. It begins at Arbatskaya Square ( Арбатская площадь ), which is located about 800 meters west of the walls of the Moscow Kremlin and where the boulevard ring crosses Vozdvishka Street ( Улица Воздвиженка ), which begins near the Kremlin . The part of this square directly adjacent to the Arbat is called the Arbat Gate ( Арбатские Ворота ), since a city wall with one of its ten entrance gates ran from the end of the 16th to the end of the 18th century - more precisely at the location of today's boulevard ring . From Arbatskaya Square, the Arbat runs almost straight ahead in a south-westerly direction and is crossed by a dozen side streets until it finally ends at Smolenskaya Square ( Смоленская площадь ), where there is an intersection with the Garden Ring . A continuation of the Arbat in a westerly direction is the eight-lane-wide Smolenskaya Street ( Смоленская улица ), which changes its name again further west and later joins the Kutuzov Prospect , which finally joins the M 1 highway to Smolensk after the MKAD ring road , Minsk and further towards Warsaw .

There are two metro stations in the immediate vicinity of the Arbat : The Arbatskaya station on the Filjovskaya line is at the Arbat Gate, the Smolenskaya station on the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya line is on the eastern side of Smolenskaya Square near the end of the Arbat.

While the Arbat formed part of the traffic route from the Moscow Kremlin to the west until the middle of the 20th century, the so-called New Arbat ( Новый Арбат , formerly Kalinin Prospect) took over this function in the 1960s . This is an expressway running parallel to the Arbat without level crossings, with sideways, very wide pedestrian promenades and a large number of high-rise buildings characteristic of the 1960s. Two decades later, car traffic on the Arbat was completely stopped and the street was converted into Moscow's first pedestrian zone in the mid-1980s . In order to avoid possible confusion with the New Arbat, the Arbat is colloquially often referred to as the Old Arbat ( Старый Арбат ).

history

Origin and Etymology

The Arbat is one of the oldest preserved streets in Moscow to this day. Exactly when it was created is not known, all that is known is that the Arbat was first mentioned in a document on July 28, 1493. On that day a fire broke out in a nearby church building, the wooden St. Nicholas Church on the Sand ( Церковь Николы на Песках ), which quickly spread throughout Moscow and devastated large parts of the city, which was then primarily made of wood. The original meaning of the toponym Arbat is not known, there are various hypotheses as to how the word could have originated:

- Probably the most widespread version says that the name comes from the Arabic word arbad , which means something like "suburb" or "outskirts". The reason for this is that before the 16th century the street and the surrounding quarters actually belonged to the Moscow suburbs, while the actual city was the Kremlin. However, there is disagreement about why a word from Arabic should have been taken over. Some city historians link this to the frequent campaigns of the Crimean Tatars against Moscow in the 15th and 16th centuries, as well as the fact that a large number of Arabic words found their way into the Turkic languages (and thus also into Tatar ).

- Another hypothesis connects the word Arbat with the Tatar word Arba - "cart" - and explains this either with the former meaning of the street as a trade route, which numerous merchants, including from the east, had traveled along with their fully loaded carts, or with the possible existence of a craft shop nearby that had produced such carts.

- In the 19th century, the historian and archaeologist Iwan Sabelin suspected a purely Russian origin of the street name. Accordingly, Arbat comes from the adjective Gorbat - "humped", which could be related to the uneven Moscow topography. However, this version is mostly disputed, as the Arbat area is unusually flat by Moscow standards.

An oriental origin of the name Arbat is therefore generally considered to be much more likely than a Russian one. This is supported by the existence of Arbatskaya Street ( Арбатская улица ) in the city of Kolomna, 100 km southeast of Moscow, which has been known since the 16th century . Since the latter was often attacked by Tatars at that time , it is reasonable to assume that this street owes its name to them.

The Arbat as a trade route and craft settlement

As early as the 15th century, the Arbat was part of a road that connected Moscow - at that time mainly the Kremlin - with the western part of Moscow and, via Poland, with parts of other European countries. This favored the mass settlement of artisanal businesses in the street area, which could quickly discontinue their production thanks to the convenient location in terms of traffic. The names of several streets adjacent to the Arbat are reminiscent of these times, including today's Plotnikow-Gasse ( Плотников переулок , literally "Zimmermanngasse") or Serebrjany-Gasse ( Серебряный переулок) , "Silbergasse". In addition to handicraft businesses, there were a large number of churches and a few houses of merchants and clergy on the Arbat of that time.

During the reign of Ivan the Terrible , the arbat also had a less glorious meaning: a palace was built nearby, which served as the headquarters of the tsar's notorious bodyguard, the oprichnina , and from which mass executions and torture of suspected treasoners were commanded, among other things. The historical novel Ivan the Terrible by Alexei K. Tolstoy says: “ The news of the terrible preparations had spread throughout Moscow, and there was soon deathly silence everywhere. The shops were closed, no one appeared in the streets, and only from time to time could one hear the galloping of the messengers of the tsar, who had been staying in his favorite palace in the Arbat. "

After the death of Ivan the Terrible and the abolition of the Oprichnina, the importance of the Arbat as a traffic and trade route grew again from the end of the 16th century. This not only favored the settlement of craftsmen, because at that time the area was no longer a suburb, but an inseparable part of the old tsarist capital and, so to speak, one of its entrance gates. Not only merchants moved here, but also the tsars , their envoys, followers and soldiers, but also foreign invaders on their way to the Kremlin and on their retreat. The Arbat has repeatedly distinguished itself as an important defense outpost of the Kremlin. At the eastern end of the road, Prince Dmitri Poscharski's volunteer army dealt a decisive blow to the troops of the Polish-Lithuanian general Jan Karol Chodkiewicz . In the 16th and 17th centuries, the state authorities had three regiments of Streliz settle on the Arbat in order to better protect the Kremlin .

18th and 19th centuries

With increasing expansion of Moscow, the Arbat became part of the city center at the latest in the 18th century and for this reason more and more a location for noble houses. After about half of the street burned down again in 1736, in the second half of the century it was so strongly characterized by magnificent aristocratic residences that it was sometimes referred to as "Moscow Saint-Germain ". In 1793, 33 of the 56 houses on the Arbat belonged to nobles and civil servants. Well-known names such as Tolstoy , Gagarin, Kropotkin, Golitsyn and Sheremetev were represented among the noble families who had their residences built on and around the Arbat . Despite its proximity to the Kremlin and its representativeness, the area was considered to be rather quiet and contemplative, if not even rural. There were hardly any manufacturers here, and trade was also rather weak compared to other Moscow districts.

Nevertheless, the Arbat continued to serve as Moscow's most important entry and exit road to the west. During the war against Napoleon in 1812, French troops led by Joachim Murat moved here on their way to the Kremlin, which the writer Leo Tolstoy mentioned five decades later in his historical epic War and Peace (see also the section on the former Nikolaus Apparition Church) .

The major fire in the bitter battle for Moscow in 1812 , which destroyed large parts of the then mostly wooden city, also left a trail of devastation on the Arbat. With the busy reconstruction of Moscow in the 1810s, however, the cityscape of the Arbat, which still exists today, gradually began to take shape. In the early 19th century, Empire houses dominated this area - some of them are still standing today - towards the end of the same century, Art Nouveau increasingly prevailed, which was often used in the construction of noble apartment buildings . Around a dozen of these tenement houses, some of which were six to seven storeys high, were unusually high for Moscow at the time and which were built with modern technology for their time, can still be found on the Arbat today. All of them were thoroughly renovated at the end of the 20th or the beginning of the 21st century and today they house elegant condominiums or offices.

At the same time, in the second half of the 19th century, the Arbat changed from a purely posh district to a popular residential area for artists. The main reason for this change was that a large number of those poets, thinkers, musicians or actors who had a decisive influence on the intellectual life of Russia at the time came from middle and smaller, sometimes impoverished nobility. Around the Arbat in particular, the so-called intelligentsia of Moscow was formed at that time , which consisted primarily of young, educated nobles who were often familiar with a socially critical attitude. At the same time, the Arbat increasingly lost its former nobility: the richest nobles, who had managed to make a lucrative career in civil service, preferred new, splendid quarters around the Kremlin and Tverskaya Street to the seemingly rural Arbat. At the turn of the century, this became a district characterized by the upscale, mostly educated middle class. In addition to artists, the Arbat was at that time especially popular with academics, including doctors and lawyers, as a place to live and work.

20th century and present

In the first two decades of the 20th century, many high and comfortably furnished apartment buildings were built on the Arbat, some of which still characterize the street scene today. At that time they were mainly inhabited by wealthy academics, occasionally also by artists. In terms of traffic, the Arbat was also continuously developed in the first half of the century: in 1904 an electric tram ran on the Arbat for the first time , three decades later it was replaced by a trolleybus line ; the previous cobblestone pavement was replaced by asphalt for the first time. In 1935 one of Moscow's first metro stations was also built on Arbatskaya Square . The fact that the Arbat was still part of the Moscow-Smolensk traffic route favored trade and made it a lively shopping street with a large number of well-known shops. It was particularly busy at the beginning of the 20th century near the western end of the street, where there was a large farmers' market (the so-called Smolensk market , Смоленский рынок ) on today's Smolenskaya Square . In addition, the Kiev train station was built a few hundred meters further west in 1899 , which further increased the influx of traders from Ukraine and southeastern Europe to Moscow via the Arbat.

Although after the October Revolution of 1917 all homeowners on the Arbat, as elsewhere in Russia, were expropriated by the new Bolshevik rulers and their houses were nationalized, the street did not lose its reputation as an artists' quarter. However, such a development gradually set in in the 1920s, when housing in Moscow became extremely scarce due to the massive rural exodus of those years and so-called communal apartments, i.e. communal apartments occupied by several families, were formed from the former apartment buildings . Increasingly, however, the district also served high-ranking officials of the Communist Party as a residential area. This is still the reason for the large number of unadorned houses in the side streets of the Arbat, some of which had to give way to historically valuable buildings. A luxury hotel was also built in the vicinity of Arbat for officials who had traveled there, the Arbat Hotel ( Гостиница Арбат ) in Plotnikow-Gasse , which still exists today .

In the early 1980s, the formerly heavily trafficked Arbat was completely closed to car traffic and converted into a pedestrian zone, which was a novelty in the Soviet Union at the time. This happened in parallel with the construction of the new building of the Ministry of Defense on Arbatskaya Square, where a large number of underground communication lines had to be laid along the Arbat. The renovation of the street, which also included the renovation of many historical buildings, was completed in 1986. Since then, the Arbat has been popular as a promenade for both locals and tourists. Today, street artists, souvenir stands and shops, restaurants, cafes and bars dominate the streetscape of the Arbat.

Attractions

Many striking or historically important buildings can still be found on the Arbat.

Preserved structures

"Praga" restaurant (house no. 2)

From Arbatskaya Square, the Arbat begins on your right with the three-story building of the Praga Restaurant ( Ресторан Прага ). This restaurant is still one of Moscow's most prominent eateries. Contrary to what the name suggests (Praga = in German " Prague ") it is not a Czech specialty restaurant.

Viewed from above, the house appears almost triangular. It has two facades, one facing Arbat and the other facing Arbatskaya Square. The building in its current form has existed since 1914, but originally dates from the late 18th century. At first it was only two stories high and housed a pub, which was also called Praga , but was considered very simple and cheap and was therefore mostly frequented by carters and other workers. That changed in the 1890s after merchant Pyotr Tararykin won the entire house playing pool. He then decided to convert the workers' pub into a posh restaurant and initiated a fundamental renovation and expansion of the building. By 1914, Praga received another floor and a new roof construction with a spacious summer terrace and the decorative dome on the corner facade. The inside of the restaurant has also been completely redesigned and divided into a large number of separate rooms, which to this day enables several closed parties to be managed at the same time.

The extensive renovation and an exquisite team of chefs and waiters - these were only employed on recommendation and after a long probationary period - gave the restaurant an excellent reputation in Moscow just a few years after it was taken over by Tararykin. It became a popular festival venue, especially among the intelligentsia, the social class that dominated the Arbat at the time. Famous artists also often dined here. Among other things, Anton Chekhov celebrated the premiere of his play Three Sisters in Praga in 1901 , a few years later the Belgian poet Émile Verhaeren was ceremoniously welcomed here by Moscow artists who had translated his works into Russian, as was the composer Nikolai Rubinstein , who was also the founder of Moscow Conservatory , has been honored here several times.

After the October Revolution, the restaurant was forcibly nationalized and since then has seen eventful times: it was completely closed during the civil war , in the later 1920s and 1930s it served as a workers' canteen and at times shared the building with a movie theater, a library and several bookstores . As a restaurant, Praga was only reopened in 1954 after an extensive renovation. Today the restaurant specializes in both Russian and international cuisine and can be assigned to an upscale price range; it is owned by the entrepreneur Telman Ismailov .

Former hotel "Stoliza" (house no. 4)

The long, three-story building to the left of the Praga restaurant dates from the 1850s. From 1865 to 1870 it served as the headquarters of the Society of Russian Doctors ( Общество русских врачей ), which was later moved to House 25 ( see below ). However, the house became particularly famous at the end of the 19th century after it had passed into the possession of the millionaire and former army general Alfons Schanjawski (1837-1905). He set up a well-equipped and at the same time rather inexpensive hotel, which over the decades has also become a popular hostel for artists and young academics. The most famous guests of this hotel called Stolitsa ( Столица , in English “capital”) included the writer Iwan Bunin and the poet Konstantin Balmont .

A few months before his death, Shanyawski bequeathed the hotel and the property belonging to it to the Moscow City Duma for the purpose of establishing a people 's university - the first university in the Russian Empire that had no admission restrictions. It was founded in 1908 and has existed as a State University for the Humanities until today , after changing responsibilities several times . Until 1920, anyone aged 16 or over could study there - in keeping with the name of the People's University - regardless of gender, social status, denomination or other characteristics. The most prominent student at this college was the popular poet Sergei Esenin from 1913 to 1914 . After Shanyawski's death, apartments were set up in the former hotel itself, some of which still exist today.

Former tenement house (house no.23)

The five-story house at Arbat 23 was built in 1902–1903 based on a design by the architect Nikita Lasarew . It is an Art Nouveau building typical of the Arbat of the early 20th century with sculptural ornaments on the main facade and eye-catching, decorative balcony grilles. Prominent residents of the house since its completion have included the sculptor Sergei Konjonkow and the painter Pawel Korin , whose most famous works include elements from several Moscow metro stations, including the stained glass of the Novoslobodskaya station on the Kolzewaya line, which is unique in the Moscow subway system . Both lived on the top floor of the house: Konjonkow in the 1900s and Korin in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Also prominent was the history of the mansion that had stood here until the beginning of the 20th century. The important Slavophile philosopher Alexei Khomyakov lived here in the 1840s, and the writer Nikolai Gogol was one of his frequent guests . From 1879 until the demolition of the house in 1901, it belonged to the lawyer Wladimir Prschewalski, the brother of the world-famous explorer Nikolai Prschewalski , who had also been a frequent visitor to the house until his death.

Former medical center (house no.25)

The house on the corner of the Arbat and Starokonjuschenny-Gasse ( Староконюшенный переулок ) also has a striking history . It was built in the early 19th century and originally belonged to a relative of the playwright Alexander Griboyedov . In 1826 the army officer, war writer and Pushkin friend Denis Davydov lived here for a few months .

At the beginning of the 1870s, the house was acquired by the businessman Alexander Porochowschtschikow (1833-1918) and completely rebuilt. A little later, he rented it to the Society of Russian Doctors , which had previously been located in House 4 , and had their headquarters set up here. This organization, founded in 1861, to which several renowned medical professors from Moscow University had belonged, was known, among other things, for its charity. For example, an outpatient clinic and a pharmacy were set up in the new Arbater headquarters, in which poor people received qualified medical help or medication during the day for free or at very discounted prices. Scientific lectures were often given in the house in the evenings. The society existed until the 1920s, at the beginning of the 20th century the number of patients at the Arbat Medical Center had exceeded a million since it was founded. A pharmacy exists in house 25 to this day.

In addition to the medical association, an art school was located in building 25 in the 1880s, until they moved to a neighboring building on Starokonjuschenny-Gasse, and the well-known painter Konstantin Juon was one of its teachers . Students who later became prominent in these painting and sculpture classes ( Классы рисования и скульптуры ), as the school was officially called, included the landscape painter Alexander Kuprin , the graphic artist Vladimir Faworski and the sculptor Wera Muchina .

The wooden house immediately to the right of House 25, with its facade facing Starokonjuschenny Alley, is also very striking. It is one of the few wooden huts typical of the country that have been preserved within Moscow's city limits. The building was built at the same time as the renovation of house 25, in 1870, also by the merchant Porochowschtschikow, who later rented it to a book publisher and a public library, among other things. At the end of the 19th century, the philosophy professor Prince Sergei Trubezkoi lived in this house.

Vakhtangow Theater (House No. 26)

The only theater on the Old Arbat - the Vakhtangov Theater - is known nationwide in Russia despite its relatively young age. The theater is named after its founder, the Russian director, actor and Stanislavski student Evgeny Vakhtangow .

Before the theater was built, an ordinary aristocratic house had stood here since the 1870s, which had first belonged to the family of the publisher Mikhail Sabaschnikow, and later to the wealthy merchant Vasily Berg. After the October Revolution and the subsequent forced nationalization of the house, it initially housed a picture gallery, the exhibition of which consisted largely of works of art confiscated from private collections of the high nobility. In 1921 the house was finally left to the recently founded troupe of the Third Studio of the Moscow Art Theater ( Третья студия Московского художественного театра ), as it was called at the time. The new stage quickly gained great popularity thanks to entertaining, innovative productions of classic and modern plays, and it was not only met with positive criticism in Russia.

The current theater building dates from the late 1940s. It was rebuilt after the old house was destroyed in 1941 during the German air raids in World War II. For the 850th anniversary of Moscow in 1997, the so-called Turandot Fountain was erected in front of the building - a tribute to the legendary success of one of the first performances of the playhouse, the play Princess Turandot in 1922.

Former tenement house (house no.35)

After its completion in 1912, the large seven-story building directly opposite the Vakhtangov Theater was one of the most elite residential areas in all of Moscow for a long time. It was built as a tenement house for a particularly well-off public and was accordingly luxuriously furnished for the time, with wide, marble stairwells, spacious elevators with mirrors and leather armchairs in their interior, as well as spacious apartments with five to eight rooms each. The outside of the house was supposed to be reminiscent of a medieval castle: with numerous bay windows and corner towers as well as massive sculptural ornaments with stylized knight figures on the facade, its style is similar to the neo-Gothic style that is otherwise not represented on the Arbat .

The exclusivity of the residential units at Arbat 35, also compared to many other Arbat apartment buildings of the time, made the house a preferred place of residence even after the forced nationalization in 1918 - only no longer for the wealthy bourgeoisie, but for statesmen and high-ranking military officials. Among its most prominent residents in the 1930s were Army General Iwan Below and the revolutionary Nikolai Podwoiski . It served as a residential building until the mid-1970s. After that, it was handed over to the Soviet Ministry of Culture, and since 1990 it has housed an actors' club as well as a variety of office space.

House No. 37, the Zoi Wall and Melnikov House

House 37, painted yellow and only two stories high, stands immediately to the right of the intersection of Arbat and Krivoarbatsky Lane ( Кривоарбатский переулок ). Today it is the only building directly on the Arbat that dates from the 18th century in largely unchanged form and was built in the Empire style that was widespread at the time . Destroyed in the major fire of 1812 and later rebuilt, the house has belonged to the Russian military since the 1840s and until today. It is currently the seat of the Moscow Military Tribunal .

The approximately four-meter-high wall that separates the property from the side of Krivoyarbatski Street has recently underlined the importance of the Arbat as a trendy district. Since 1991 it has traditionally been a meeting place for rock fans, who remember Wiktor Zoi , the musician who died in an accident in 1990 and founder of the Russian cult band Kino . Meetings of his fans take place here, especially on the days of the rock idol's death. His songs are often played and sung and the wall is painted with pictures and quotes from Zois and declarations of love for him and his life's work. Similar Zoi memorial walls were built in several other Russian cities in the 1990s based on the Arbat model. The origin of the Moscow original on the Arbat of all places, however, cannot be explained with a personal reference to Zois to the street, as Zois did not live there.

Also worth mentioning is the striking Melnikow House, which has been attracting tourists and onlookers without interruption since its construction. It is located at 10 Krivoyarbatski Street, diagonally behind 37 Arbat House. It was built by Konstantin Melnikow , who was one of the most famous architects of the Russian avant-garde in the first half of the 20th century . The house, which was completed in 1929, is one of the most striking buildings in the center of Moscow due to its bizarre shapes - it consists of two cylindrical towers with numerous raised hexagonal window openings. After its completion, it was also the only residential building in the center of socialist Moscow that belonged entirely to a private person (here: Melnikow). The son Melnikov, who died in 2006, bequeathed part of the building, which is now a listed building, to the Russian state. The often-voiced plans to set up a museum there have so far failed due to legal disputes between the heirs and the relatively weak statics of the house, which do not allow mass public traffic without costly stabilization measures beforehand.

Okudjava house (house number 43) and monument

This house is best known for the poet, musician and songwriter Bulat Okudschawa , sometimes called " Bob Dylan of the Soviet Union", who had lived here since he was born. Just one house further, at the intersection with Plotnikow-Gasse, there has been a memorial to the artist, who died in 1997, since 2002, which, in addition to the actual statue, includes a sculptural composition with an attempted representation of a typical Arbat backyard. This composition is an allusion to the romanticism of the old Arbat, which Okudschawa, a staunch local Arbat patriot throughout his life, processed in a large number of his poems and songs. For example , the song about the arbat written in 1958 says:

“You flow there like a river. Strange name you!

Your asphalt is like glass, a river as clear as water.

Oh Arbat, my Arbat, you are my whole being

to me , You are joyful and also full of grief for me [...] "

The inner courtyard of house 43 with trees that were planted by the poet himself at the time is a reminder of Okudschawa's youth. However, his museum is not located on the Arbat, but in the former artists' village of Peredelkino near Moscow, in the former dacha of Okudschawas.

Rybakov House (No. 51)

House 51 is reminiscent of another author whose life and work are closely connected to the old man Arbat: The Soviet writer and critic Anatoly Rybakov , who later emigrated to the USA, lived here for many years . The building was not only known through him, however. It was built in 1903 and originally served as a tenement house. With eight floors, it was one of the tallest residential buildings in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century: even the other tenement houses on the Arbat were no more than six or seven floors high at the time. For this reason it was precisely House 51 on the roof of which the Bolsheviks had positioned machine-gun shooters during the October Revolution in 1917 .

While the upper floors of the house housed residential units for wealthy tenants at the beginning of the century, a movie theater called Arbatsky Ars ( Арбатский Арс ) was well-known in Moscow until the 1980s . Rybakov, who had lived in house 51 in the 1930s, mentioned this and the movie theater later in the opening scene of his novel The Children of Arbat , the plot of which also takes place in the early 1930s:

- “ Sascha Pankratow left the house and turned left - to Smolenskaya Square. In front of the 'Arbatski Ars' cinema, young girls were already strolling up and down, always in pairs, girls from Arbat, from Dorogomilovo and Pljuschtschicha streets, their coat collars quickly turned up, their lips made up, their eyelashes brushed up and washed in their eyes waiting curiosity, a colorful silk scarf around the neck, now the latest craze on Arbat in autumn. The performance had just ended and the audience streamed out through the rear courtyard. In order to get onto the street, people had to squeeze through the narrow gate, where on top of that an exuberant crowd of teenagers, the actual regulars here, were joking around. "

- “ A day came to an end on Arbat. "

Pushkin House (house number 53)

The rather simple two-story house near the western end of the street is one of the destinations regularly visited by tourists on the Arbat. In 1831 it was the residence of the poet Alexander Pushkin for a few months , who spent his honeymoon here with her after his wedding to Natalia Goncharova . The house, which was built in the 1770s, belonged to the family of the civil servant Nikanor Chitrowo, with whom Pushkin had signed a rental agreement for a five-room apartment on the first floor of the house with an initial term of six months in early 1831. This happened shortly before the wedding of the poet, on February 18, 1831, to 18-year-old Natalia Goncharova, daughter of a Volokolamsk landlord. Although Pushkin had paid six months in advance for the apartment, he and his wife only stayed there for just under four months before they moved to St. Petersburg together .

After Pushkin moved out, the house had changed hands several times over the decades and served as an apartment building for a long time; one of its prominent residents of the late 19th century in the 1880s was the lawyer Anatoly Tchaikovsky, brother of the composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky , who visited him here several times. After the October Revolution the house was nationalized and deteriorated increasingly. It was not until 1974 that the Moscow city administration placed it under monument protection and decided to set up a publicly accessible Pushkin Memorial House there. The museum opened on January 18, 1986, on the 155th anniversary of the poet's wedding.

Andrei Bely House (house number 55)

Immediately to the right of the Pushkin House on the corner of Arbat and Deneschny Alley ( Денежный переулок ) there is a four-story former tenement house from 1877. In the 19th century, part of the local apartments belonged to Moscow University and served as a residence for some of its professors. One of them was the mathematician Nikolai Bugajew (1837–1903), whose son Boris was born here in 1880 and lived until he was 26 years old. Later he was best known under his stage name Andrei Bely as an important Russian poet of symbolism . Bely is still considered the most prominent resident of house 55. His first works were created here, and Bely also received his friend Alexander Blok , who was also a famous poet of the so-called Silver Age at the time , in his Arbat apartment on the second floor. Today a small museum has been set up in it in memory of Andrei Bely.

Smolenskaya Square

Both the right and left sides of the Arbat are closed off by buildings from the Soviet era. The last Arbat house on the right side of the street is house 54, one facade facing the Arbat and the other facing the garden ring . It was built as a residential building in 1928. On its ground floor there is a large shop that has housed a supermarket of the classy chain The Seventh Continent since 1997 . In the 1930s there was a department store belonging to the state-owned Soviet chain Torgsin ( Торгсин ), whose range was primarily aimed at foreign customers who brought in foreign currency ( Torgsin was a made-up word and stood for Tor gowlja s in ostranzami , in German: “Handel mit Foreigners ”) as well as somewhat better-off Soviet citizens and was accordingly richer than in ordinary department stores in the times of scarcity . This shop is mentioned in a scene from the satirical novel The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov . There the reader learns, among other things, what the department store must have looked like from the inside back then:

- “ There were hundreds of bales of brightly patterned calico on the shelves, behind them were piles of mitkal, chiffon and tails, and a little further away you could see whole stacks of shoe boxes. There were a couple of women sitting on low chairs with a worn old shoe on their right foot and a shiny new shoe on their left, which they worriedly stamped on the carpet. Somewhere in the background gramophones were singing and playing. "

After the chain was dissolved in 1936, the restaurant housed an ordinary grocery store until the mid-1990s, albeit quite well-stocked by Soviet standards.

The entire left section of the Arbat from the Deneschny-alley by road end of the mighty cake style -Construction of the Russian Foreign Ministry determined and its wings. The 172-meter-high skyscraper with the main facade facing the garden ring, which belongs to the ensemble of the so-called Moscow Seven Sisters , was built in the years 1948–1953, with part of the side wings being completed in the mid-1930s. The building is one of the typical structures of the Stalin era and is probably the most unusual part of today's Arbat street scene, mainly due to its towering height.

Structures not preserved

Both the German air raids in World War II and the mass demolitions during the Soviet era, especially during the ideologically motivated renovation of Moscow's city center in the 1930s, did not survive a number of buildings on the Arbat.

Former artist workshop (house no.7)

The odd side of the Arbat opens today an elongated office and commercial building built in 2004, which among other things houses the headquarters of the mineral oil company TNK-BP . Until it was demolished in the 1970s, houses 1, 3, 5 and 7 stood at this point. House 7 was historically particularly interesting, a two-story building from the early 19th century that was built in the 1860s and 1870s had belonged to a distant relative of the poet Ivan Turgenev . At that time one of Moscow's first public libraries was located here. This evidently not only attracted the interest of the educated Arbater: in 1875 their book collections were confiscated by the police because they contained a number of liberal and revolutionary writings that were forbidden by the censors, including books by authors such as Herzen , Tschernyshevsky , Marx and Lassalle . The library then had to be closed, and the building has changed hands several times since then.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the house initially housed a small movie theater called Grande Parisienne . In 1918 a literary café was opened in its former premises, in which the poet Sergei Jessenin read from his poem Pugatschow , which he had just written , in 1921 . In the 1920s, however, Haus 7 was best known for the MASTFOR artist workshop set up here , a small theater founded by the German-born director Nikolai Foregger (originally: Freiherr von Greifenthurn). The performances of this theater were sometimes considered to be quite frivolous and were therefore controversial in intellectual circles. Nevertheless, some young artists who later made it famous took part in the performances, including the directors Sergei Jutkewitsch and Sergei Eisenstein and the futuristic poet Vladimir Mayakovsky . The artist workshop MASTFOR existed for two years, from 1922 to 1924.

The "haunted house" (house no. 14)

The former house at Arbat 14 fell victim to the German air raids in 1941. The building was an Empire mansion, which belonged to the Petersburg judge Manukov in the 18th century. He left the house in 1728 as a dowry to his daughter on the occasion of her wedding to Vasily Suvorov , an officer of the elite Preobrazhensky regiment and father of the later famous military leader Alexander Suvorov . The latter was most likely born in this house in 1730.

In the first half of the 19th century the house belonged to the well-known state archivist Michail Obolensky. It became quite notorious as a haunted house towards the end of the century. Many neighbors reported at the time that strange noises, sometimes knocking and screaming, could be heard in the empty building at night. These rumors soon spread across Moscow and sparked innumerable speculations: sometimes there was talk of the unredeemed ghost of a former tenant of the house who had committed suicide there together with his entire family , sometimes of a meeting place for Moscow Satanists . Finally, the city administration had the house surrounded and thoroughly examined by the police - and they finally found a group of criminals there who had hidden from the state and apparently only dared to get out of their hiding place at night. By then, the legend of a haunted house had spread so widely that it was mentioned in documentaries by the well-known publicist and city historian Vladimir Gilyarovsky .

To this day, the place where the haunted house was still not built on. The house number 14 belongs to a small restaurant building to the left of it, while at the place of the destroyed house there is a small garden, which is separated from the Arbat by a wall.

Nikolaus Apparition Church

In the place of today's house 16, right on the corner of Serebrjany-Gasse, the Nikolaus -Apparer-Church (also Nikola-Jawlenny-Church , Церковь Николы Явленного ) stood until the beginning of the 1930s , one of the previously numerous Russian Orthodox Church building of the Arbat area. It was consecrated to St. Nicholas of Myra , who was widely venerated in Russia . Erected at the end of the 16th or beginning of the 17th century by the Strelizi , who then resided on the Arbat , this church was architecturally considered to be one of the most beautiful in the district: in particular, its pointed bell tower, the roof structure of which was adorned by a total of 40 decorative arched windows typical of ancient Russian sacred buildings. was noticeable about the building.

The Nikolaus-Apparer-Church also became known through a modern legend , according to which it served the French Marshal Joachim Murat as a stopover on his campaign to the Kremlin during the war against Napoleon in 1812 . Exactly this legend was later adapted by Leo Tolstoy in his historical novel War and Peace . There it says:

- “ In the fourth hour of the afternoon, Murat's troops entered Moscow. A detachment of Wuerttemberg hussars rode in front, followed by the King of Naples in person on horseback with a large retinue. "

- “ Approximately in the middle of the Arbat, near the Nikola Jawlennyj Church, Murat stopped and waited for the advance guard to report the situation at the citadel of the city 'le Kremlin'. "

- “ A group of Moscow residents who had stayed in the city gathered around Murat. Everyone looked at the strange, long-haired general, adorned with feathers and gold, with shy amazement. "

But even such historical importance could not protect the church from the massive destruction of the Russian churches in the early years of Stalin rule: The Nikolaus-Apparer-Kirche was closed in 1929 and in 1931, almost at the same time as many other important Moscow churches (including the monumental Christ the Savior Cathedral ), including the bell tower, demolished.

Nikolaus Church on Plotnikow-Gasse

At the corner of Arbat and Plotnikow-Gasse, at number 45, there is now a residential building built in 1935, which can essentially be assigned to Stalinist architecture. Until the 1990s, there was a large grocery store on its ground floor, and the apartments above were given to party officials and particularly deserving citizens. Prominent residents of the house included the writer Marietta Schaginjan and the polar explorer Iwan Papanin .

A church stood on the site of the house until it was demolished in 1932. It was built in the early 17th century and originally served as a place of worship for the residents of the carpenter's settlement. Like the Nikolaus-Apparent Church, this church was named after St. Nicholas of Myra. In total there were three Nikolaus churches on and around the Arbat; the third of them was the church on the sand , the fire of which in 1493 had begun the written history of the Arbat. It was not located directly on the Arbat, but in the nearby Nikolopeskovsky Alley ( Николопесковский переулок ).

supporting documents

Individual evidence

- ↑ Immanuil Levin, p. 3.

- ↑ marshrut-turista.ru; accessed on September 29, 2014 ( Memento from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ stariyarbat.ru: origin of the name; accessed on March 11, 2008 ( memento of March 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Alexej Konstantinowitsch Tolstoj: Ivan the Terrible. Moewig Verlag, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-8118-0023-X .

- ↑ stariyarbat.ru: From the Middle Ages to the 18th century; Retrieved on March 11, 2008 ( Memento from March 25, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Jewgeni Jurakow, Rambler, June 5, 2006; Retrieved on March 3, 2008 ( Memento of August 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Immanuil Levin, p. 44.

- ↑ stariyarbat.ru: The ambulatory; accessed on March 31, 2008 ( Memento of March 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Aleksey Mitrofanov, p. 207.

- ↑ Immanuil Levin, p. 100.

- ↑ lenta.ru news, March 13, 2006; accessed on March 31, 2008

- ^ Leonhard Kossuth (Ed.): Bulat Okudshawa. Romance from the Arbat. Translation by Werner Bernreuther. Verlag Volk und Welt, East Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-353-00245-6 .

- ↑ Anatolij Rybakow: The children of Arbat [Deti Arbata]; Translation by Juri Elperin; Publishing house Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-462-01938-4 .

- ↑ Immanuil Levin, p. 172.

- ^ Official website of the Pushkin House; accessed on April 27, 2008 ( memento from June 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Official website of the Andrei Bely Museum; Retrieved April 27, 2008

- ↑ Michail Bulgakow: The master and Margarita; Translation by Thomas Reschke; Luchterhand-Verlag, Neuwied and Berlin 1968.

- ↑ Immanuil Levin, p. 86.

- ↑ Aleksey Mitrofanov, pp. 168–174.

- ↑ Complete edition of the poetic works of Leo Tolstoy, Volume VI, translation by Erich Boehme; Malik-Verlag, Berlin 1928.

literature

Non-fiction

- Immanuil Levin ( Иммануил Левин ): Arbat. Odin kilometr Rossii ( Арбат. Один километр России ). Galart Publishing House , 2nd edition, Moscow 1997, ISBN 5-269-00928-5 .

- Aleksej Mitrofanov ( Алексей Митрофанов ): Progulki po staroj Moskve: Arbat ( Прогулки по старой Москве. Арбат ). Ključ-S publishing house , Moscow 2006, ISBN 5-93136-022-0 .

Fiction

- Anatoli Naumowitsch Rybakow : The children of the Arbat . Novel . Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-7466-1823-1 .

Web links

- Brief description of the Arbat on russlandjournal.de

- Official Website of the Arbat District (Russian)

- Streets of Moscow: The Old Arbat ( Memento of January 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (Russian)

Coordinates: 55 ° 45 ′ 4 " N , 37 ° 35 ′ 46" E