heraldry

Heraldry , also known as heraldry , is the study of coats of arms and their correct use. For coats of arms and the heraldry include the heraldry (the design of Arms) and legal regulations on arms use. Heraldry thus comprises different areas:

- Heraldry as a science deals, among other things, with the historical development of the coat of arms and the meaning of the symbols on the coat of arms.

- Heraldic art is the design of coats of arms according to traditional heraldic rules that go back to the 12th century.

- The blazon is the description of the coat of arms according to the rules of technical language.

- The coat of arms law determines the rules according to which a coat of arms is to be used.

The word heraldry goes back to French [science] héraldique literally means heraldic art . In fact, Herold Art used to be a common name for the heraldry. The herald of the coat of arms was the expert in reading the coat of arms and recognizing who wore it. Previously, the supervision of the coat of arms was exercised by the heralds, at whose head a coat of arms king could stand (still in Great Britain today ). Today the heraldic associations continue this supervision in an informal manner.

In addition to a few preserved original shields, seals ( sphragistics ) and registers of the heralds' coats of arms , which they created on the basis of their official area or on special occasions, form an important basis for historical heraldry . Also bookplate (book owner characters) from the late Middle Ages that were running at the time primarily as a coat of arms, heraldry serve as a research base. As a discipline of history, it belongs to the historical auxiliary sciences . Philipp Jacob Spener is considered to be its scientific founder for the German-speaking area .

history

The history of heraldry is divided into three main periods:

- the period from around the 11th to the 13th century when the shield with the image represents the actual coat of arms;

- the period from around the 13th to the 15th century, the heyday of heraldry, in which helmets and jewelry (such as wings, feathers, horns, hats, hulls) were added to the shield;

- the time since the 16th century, in which the shield is no longer used as a weapon, but only as a badge of honor and more and more insignificant ingredients are added.

The main sources for scientific research into the coat of arms are:

- literary sources: documents, feudal letters, family books, tournament descriptions, family books and nobility letters;

- pictorial sources: monuments, tombstones, paintings, church flags, coats of arms, seals, coins and glass windows;

- documented sources: heraldic collections, heraldic books, heraldic scrolls and death shields.

prehistory

It was customary for the warriors and especially the military leaders of the peoples of Babylon, Persia and China to put various symbols and figures on their shields and flags. Various animals such as lions, horses, dogs, boars and birds can also be found on the shields of the ancient Greeks. Furthermore, the legions and cohorts of Rome also had their own symbols and insignia.

During this time, however, the pictorial elements on the shields had primarily a decorative and apotropaic function. In the great battles, the field colors of the standards , pennants and clothing of the warriors were decisive in order to be able to distinguish them from a great distance. However, the field colors could be redefined for each campaign, in principle even for each battle - much like soccer teams can choose different jersey colors for each season and each game.

The permanently assigned flags emerged from the variable field colors . Even today, military associations have their own war flags, colors and symbols in addition to the state flags. The shield coats of arms later emerged from the various shield shapes, shield colors and applied shield symbols of the warrior associations.

middle Ages

With the rise of feudalism in the Middle Ages, the ruling houses chose their own symbols. During the great campaigns, dozens of noble houses were able to move out together, and their armor had increasingly fewer design differences. The colors and symbols on the shields became increasingly important, and several colors were combined in simple geometric shapes.

Until the middle of the 12th century, however, these colors and symbols were personal. It was up to the wearer which symbols he chose or whether he changed them, possibly several times in life. The 11th century Bayeux Tapestry shows various shields and flags from some Anglo-Saxon and Norman warriors who took part in the Battle of Hastings (1066).

In the second half of the 12th century, face protection on helmets expanded from a simple nasal to a completely closed pot helmet , which now hid the wearer's face. The crusades led to many royal houses from different kingdoms going into battle together. This provided an additional reason for heraldry to develop.

Perhaps as a result of the confusion in the First Crusade (1096-1099), hereditary shields found widespread use thereafter. Even the new crusaders of the second crusade (1147–1149) felt it was an honor when they were allowed to use the same sign on the shield as their ancestors among the first crusaders. On all later crusades, the heraldic symbols were emblazoned from afar on the shields, on the chest and back, right down to the horse blankets and the pennants of the lances.

Tournaments

Another reason was provided by knight tournaments , which were both a weapon exercise and a show. The fights, to which hundreds, often thousands of spectators came, were heavily ritualized. Those who were defeated in a duel often lost their horse and armor, which was very expensive at the time. Under the full armor of the early 12th century, the knights could hardly be recognized, so the tournament participants wore their own coat of arms or that of their liege lord on the shields.

If it was important to recognize your own troops in war battles, you had to be able to distinguish the individual participants in the tournament. For the respective opponent the shield adorned with the coat of arms of the opposite was enough , but for the crowd of spectators who wanted to recognize their favorites beyond a doubt despite armor, a few more ideas were required. So people began to repeat the coat of arms on the linen tunics that were worn over the chain mail, to attach them to the horse blankets and to come up with highly recognizable, highly visible, original emblems that were attached to the helmet.

So the tournament being for the spread of arms and especially for the creation of imaginative is Helmzier responsible. The coats of arms from this early period of heraldry in the 12th century still had a practical function almost entirely. The blazon of the symbols with which arriving knights were proclaimed at the tournaments was very important . According to the herald's call, everyone could assign armored knights to a house. The colors and elements described showed the relationships between the houses, and some coat of arms symbols became so well known that they were given their own short names.

Heralds

In equestrian battles, the knights had retained their personal mark - i.e. their coat of arms - on shield, helmet and horse throw. Hence the idioms “arm yourself” and “put on your armor”. Since there was no such thing as a national flag in those times, one had to be able to distinguish between friend and foe in the myriad of symbols and colors. The specialists for it, gifted with a good memory, were the heralds of the heralds . Their task was to get to know the assembled knights in army camps and to exchange ideas with other heralds. Because their code of honor forbade them to scout out the enemy positions, they were also allowed to enter the opponent's camp to report to their masters "rank and name" so that they could compete with worthy opponents in battle.

Renaissance

The importance of knight tournaments waned with the burgeoning renaissance, and the rapid spread of firearms in the 16th century quickly put an end to the confrontation with shield, lance, armor and sword. The only remnant was the ring piercing - a less dangerous variant of medieval jousting , in which kings were fatally injured.

In the meantime, however, the coats of arms also had a sovereign function. Most of the knights of the Middle Ages were illiterate, but knowing the symbols of the coat of arms allowed them to assign documents. At the end of the 13th century , the office of the herald , who had to know the name, title and coat of arms, was created.

The burgeoning coat of arms carried over to other areas, and was used in addition to the military function for legal forms - the coats of arms were emblazoned on seals, palace portals, city gates and fortifications. This was also continued with the end of the knightly era. Freed from some practical necessities, the representations became more artistic and many coats of arms were underlaid with legends of their origin.

Baroque and Rococo

The baroque finally led to exuberant coats of arms, in which the classical proportions are abandoned. The framework and the showpieces were in the foreground in the design. The traditional coat of arms was given up, especially in the Rococo, in favor of richly ornamented cartouches. The heraldic elements lost their intrinsic value and were partly used again purely for decorative purposes as a mere filling of lavishly designed cartouches.

Modern times

The inclusion in the roll of arms guaranteed that no one else was allowed to wear the same symbol. This represents an important forerunner of the trademarks of the civil era.

In France, the coat of arms was reorganized under Emperor Napoleon I , see Napoleonic Heraldry .

In the English-speaking world, state herald offices have been preserved to this day , which check the authorization of the coat of arms and record the chosen coat of arms. Many British knights also have their own coat of arms, such as Sir Elton John and Sir Paul McCartney .

According to German law, every natural or legal person is allowed to choose and use their own coat of arms - it is then protected against arbitrary use by others, analogous to the naming rights in the German Civil Code .

In Austria , only regional authorities (the federal government, the federal states and the municipalities) are allowed to use a coat of arms, even if the coat of arms can be protected as a trademark . However, the use of coat of arms by citizens is tolerated in Austria. This is problematic as private coats of arms do not enjoy any legal protection.

The design of the coat of arms (heraldic art)

Heraldic elements

The graphic opposite shows components of a coat of arms. In heraldry, the coat of arms is seen from the point of view of the wearer of the shield. “Right” is the left side of the coat of arms from the viewer, “left” is the right side of the coat of arms from the viewer.

A monochrome coat of arms can be a complete coat of arms. However, this is unsuitable for expressing the various class attributes and family relationships of the coat of arms owners. Very simple coats of arms can only be found on old and generalizing coats of arms such as the shields of the Swiss country teams. On the other hand, a full coat of arms is entered in the coat of arms , which contains at least one shield with a surrounding status symbol.

Knights have a helmet on their shields . The helmet with sessile crest and surrounding helmet covers is the most common complement an escutcheon to the full coat of arms. It represents the festive appearance of the knight when entering a tournament. The lack of helmets regularly expresses the owner's non-combatant status, mainly in the case of city and church coats of arms. In city coats of arms one often finds a wall crown instead .

A coat of arms of the high nobility often has a shield holder , a coat of arms or, in the case of ruling monarchs, a coat of arms tent as ingredients . However, these are not absolutely necessary for a complete coat of arms.

In rare cases, the full coat of arms includes several shields, several helmets, shield holders and banners with motto .

Common characters

Common figures are the names of the diverse figures that enrich the coat of arms beyond the tinctures. There are numerous motifs from animate and inanimate nature. They can be divided into

- natural figures (such as people, animals and plants),

- Fantasy creatures (such as mythical creatures and hybrid creatures ) as well

- Artificial figures such as towers and walls ( castle ), weapons, tools and other everyday objects (e.g. wheel ), although there can be unreal mixed objects here too.

Heraldic animals make up a large part of the common figures. Lions , bears , leopards , eagles , cranes , dolphins , rams and bulls are very popular , as are mythical creatures such as the griffin , the unicorn , the dragon , the double-headed eagle and the dragon . Heraldic animals in city and state coats of arms are often symbols for the city or the region, for example the Berlin bear or the Sachsenross .

Popular plant figures are the rose , the lily (fleur-de-lis) or the "strong" oak .

Examples of Christian symbols in heraldry are different crosses (e.g. Passion Cross and Maltese Cross ), the key (e.g. in the coat of arms of Bremen ) and the bishop's staff (e.g. as a Basel staff in the coat of arms of Basel ).

Shield divisions

1 divided, 2 divided

3 and 4 mixed forms

5 square, 6 square with heart shield

7 and 8 diagonally divided

A heraldic shield can be divided into fields by lines that run horizontally, vertically or diagonally from shield edge to shield edge. The geometrical division of the shield with one or more such lines creates a heraldic image . In the simplest cases, the sign is divided into two different colored fields by a horizontal or vertical line. Different types of shield division can result in certain figures, e.g. B. Beam , sloping beam, pole or continuous cross. Overall, there is a large variety of herald images.

A shield head is created when roughly the top third of the shield is severed. The corresponding lower third is called the shield base . If a vertical and a horizontal line divide the shield into four quarters, one speaks of a crossing or a "quartered" shield. Not to be confused with this is the free quarter , a small field in the right or left upper corner of the shield. The free quarter is rare in German heraldry, but it is an important element in Napoleonic heraldry in France.

The shield can not only be divided into fields with straight lines, but also with cuts of any shape , e.g. B. divided in wave cut, split in pewter cut, a double cloud border , shield head separated by tooth cut . These also count among the heraldic images.

Additional character

Extra characters are smaller characters that in some cases can be traced back to a specific person. The thread is a narrow sloping bar drawn over the coat of arms, which, drawn diagonally to the right from the right upper corner to the left lower corner,denotesa younger or secondary line, and, obliquely to the left, an illegitimate born (bastard, hence bastard thread ) of the sex. When the thread is shortened, it is called break-in (right or left) and as such has its place in the heart of the shield. Many coats of arms - especially in Spain (see the Portuguese national coat of arms ) - have a shield border in a contrasting color , which in turn can be covered with small figures. Another symbol is the tournament collar , which is used especially in English heraldry to differentiate between family members (marking the first-born) and which is removed when the successor begins. Further markings are common to differentiate between the individual descendants of a coat of arms.

Heraldic coloring

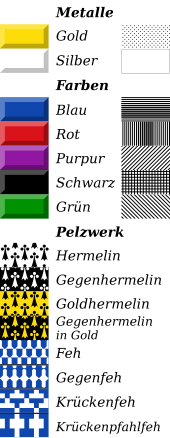

The coloring of coats of arms is called tinging (from Latin tingere "to color"). Contrary to common usage, gold and silver are not referred to as "colors" in heraldry, but rather as "metals". Also yellow and white are not heraldic colors. Rather, yellow and white in heraldry are synonymous with the metals gold and silver. Yellow and white are only used to represent gold and silver in the painted or printed reproduction.

Only a very limited range of color values and patterns is used for heraldic representations:

- the metals gold and silver (or alternatively yellow and white).

- the heraldic colors red , blue , black , green . (More rarely also purple and so-called natural colors such as brown and gray .)

- the furs. These are surface-filling pattern shapes that go back to animal skins, for example ermine .

Metals, colors and fur together are called tinctures in heraldry . The following rules and recommendations apply to its use:

- Coats of arms should also be kept simple in terms of color, i.e. as few different colors and metals as possible in one coat of arms.

- Pure colors without shading, gradients or nuances are used.

- Natural colors (brown, gray, flesh color ) are considered unheraldic. If possible, only heraldic colors (red, blue, black, green) and metals (gold, silver) should be used.

- All heraldic colors are of equal importance. There are no colors that rank above others.

- In principle, every object can be displayed in any heraldic color.

- In a coat of arms, metal must not border on metal (i.e. gold not on silver), colors must not border on colors. By juxtaposing metals and colors in a coat of arms, a strong contrast effect is achieved, which makes the coat of arms recognizable from a great distance. This rule has a prominent meaning and is often referred to simply as the " heraldic color rule ".

- Furs can be used in combination with both metals and colors.

The tinctures are indicated in the blazon. In the case of black and white depictions of coats of arms, hatching is used as a substitute to mark metals and colors.

Shield shapes and helmets

Influenced by the development of weapon technology and artistic styles, the depiction of the coat of arms also changed over the centuries. The earliest shield shape used is the triangular shield used in the High Middle Ages from the 12th to the 14th century (example: Essen ), the sides of which are curved outwards. The associated helmet is the pot helmet, which is partially provided with a fabric cover.

In the 13th century the semicircular shield was created, which offered more space for the depictions of coats of arms. In particular, multi-field coats of arms, which now appeared, require the larger space in the lower half of the coat of arms. The tub helmet that emerged from the pot helmet is already provided with fabric-like helmet covers that are only slightly incised. From the bucket helmet the stech helmet emerged in the 15th century , which since Emperor Friedrich III. Gained importance as a symbol of the civic coat of arms; it was characterized by more strongly incised and rolled helmet covers. The piston tournament helmet , which appeared around the same time , is also referred to in heraldry as a bow helmet or spangenhelm. The helmet covers are no longer recognizable as strips of fabric, but resemble ornamental foliage.

The representations of the coats of arms show more and more unheraldic (i.e. different from the shields actually used) shield shapes: The Tartsche , a shield used in tournaments with a round or oblong-oval incision on the (heraldic) right side, was the spear rest (support of the tournament lance) the last shield corresponding to a real battle shield, the shields with spear rests on both sides, on the other hand, no longer have a real equivalent, and the rolled-up sides of the Renaissance shields, which take into account the increasing need for jewelry, exist only on paper or as plastic in wood or stone, but not on the tournament field. Another variant is the symmetrical, elongated, polygonal Ross front shield , which was mainly used in Italy.

There is increasing evidence of a development that will fit the contents of the label into a decorative cartridge that no longer has anything to do with a real label edge. Finally, the actual shield disappears into the exuberant frame of the Baroque and Rococo periods and is surrounded by shield holders, coats of arms and tents as well as other accessories. This period is known as the decay of heraldry. Only the rediscovery of the coat of arms during the second half of the 19th century led to a new heyday of heraldry. Well-known artists such as B. Otto Hupp used forms from the 13th to 15th centuries for their coats of arms.

Coat of Arms Association

If it is necessary to combine at least two coats of arms of different bearers in one coat of arms due to marriage, inheritance or expansion of territory, different rules apply. These are strongly influenced by the intention of the leader of the family coat of arms. The merging can be achieved by laying on , grafting , entangling or edging , and in general only by positioning the coats of arms.

General design rules

In order to make a coat of arms clearly recognizable, the number of colors, fields and figures should be as small as possible. The figures should largely fill out the sign: “Less is more”.

The color rule must also be observed: “Of two fields of a coat of arms, one should be tinged in one color, the other in a metal.” This rule also applies to the shield field and a common figure placed on it.

A typical way in heraldry to expand the number of coat of arms motifs is tinging in mixed or mixed up colors. With this technique, the shield is divided into two fields, for example, with a common figure or another herald's image each showing the color of the opposite field.

Blazon

"The coat of arms of the city of Leipzig shows in a split shield on the right in gold a red-tongued and red- armored black Meißner lion rising to the right, two blue Landsberg posts in gold on the left ."

The blazon is the description of a coat of arms in brief technical terms. Based on the blazon, the coat of arms should be clearly recognizable so that it cannot be confused with another coat of arms. The expression comes from the French word blason "coat of arms". The main features of the artificial language of blazon originated in France when the first coats of arms scrolls and registers were created in the 13th century. Just as the entire coat of arms developed and consolidated step by step, the blazon was also more finely worked out over time, especially in the 17th and 18th centuries. Century.

With the blazon, “right” is the left side of the coat of arms from the viewer, “left” is the right side of the coat of arms from the viewer. The components of the coat of arms are described in a fixed order: first the shield, then the upper coat of arms , and finally, if necessary, the shield holder , coat of arms and other gems .

For a more precise indication of positions within the shield, designations can be used that are based on the herald's pictures , e.g. B. shield foot , right or left flank , heart point . Abaissé is the name of a humiliated coat of arms. Growing is called a mean figure that sits so low that it is cut off at the bottom.

Heraldic registers

Coats of arms should be registered in a register of coats of arms for reasons of proof. Originally, heraldic registers were kept in a heraldic scroll, a scroll made of parchment . The term heraldic roll has survived to this day, although heraldic collections are now published in book form ( Wappenbuch ).

Heraldic associations maintain registers of coats of arms today . For example, the Herold association, founded in 1869, runs the German coat of arms . In addition to the formal examination of the design of the coat of arms, the prerequisite for the registration of a new coat of arms is the determination that the coat of arms is not already used by others.

Special areas of heraldry

Ecclesiastical heraldry

In the case of the heraldry of the Catholic Church, a distinction must be made between purely spiritual coats of arms or a church position associated with secular rule. For secular and ecclesiastical lords, such as prince-bishops , the coats of arms correspond to those of other territorial lords, with a full coat of arms (helmets and helmet decorations), enriched with church insignia (crook, cross) and secular insignia (sword). For purely ecclesiastical office holders, a system of ecclesiastical official heraldry without helmets and helmets was developed, instead with priest hats ( galero ) and strings with tassels on both sides of the shield, the number and color of which mark the rank of the wearer. In historical times, the shield contains a combination of the coat of arms of the office (diocese, monastery) and the family, in a quartered (squared) shield. The official coat of arms remains, the family coat of arms changes. More recently, this strict scheme has been abandoned and bishops' coats of arms have been composed more freely. Thus, church coats of arms are overall personal coats of arms, since they are not passed on in this form within a family.

The Evangelical Church has no such system.

Colonial coat of arms

Colonial coats of arms are the coats of arms prescribed to the states in the colonies of the European states by the colonial powers according to their and the European rules of heraldry. Since heraldry had little or no beginning in the colonies, coats of arms were declared valid, contrary to the heraldic rules. Coats of arms show essential parts of their colonial power. Example: Portugal put the Quinas in the shield, England their lions and France the lilies in Canada. Many heraldic sayings under the shields are borrowed from the mother country. So that of Jamaica can be counted among the older coats of arms . It was introduced by England around 1692.

With the gradual end of the colonial era in many countries, new coats of arms were created by the independent states or those that had been used up until then were only adapted. Revolutionary symbols such as the rising sun , stars , loyal hands and arms, a cornucopia or a Jacobin cap can be found more frequently. Heraldic currencies are often the same: freedom - equality - brotherhood and the laurel wreath or branch is around the shield. In many countries, in the heraldic sense, often only national emblems were created when creating new ones, since no shield, the essential part of the coat of arms, was used. Much is only arranged around a white surface. Also unheraldische colors are used and it is to recognize the propensity for realistic spatial representation.

Student heraldry

The basic rules of general heraldry also apply to student color combinations. In some areas, however, the student heraldry has peculiarities that result from the special use of ribbon and tip . Ribbon and tip came up around 1800 with the corps and fraternities , which were the first to wear the ribbon as a chest ribbon. Before that, the strap was mostly worn as a watch strap and ended in the left vest pocket. The remnant of the strap hanging from the watch pocket, which was worn alone during the times of the persecution of the fraternities and from which the tip emerged, showed the head color of the strap not on the heraldic right, but on the heraldic left. It follows that, contrary to the general rule, vertical student colors are read, i.e. not from left to right for the viewer, but from right to left. This is especially true for corners and flags hung vertically on the wall. If the flag hangs freely in the room, e.g. B. on a flagpole, the general rule of heraldry applies that the colors are read from left to right for the viewer.

However, caution is advised with student coats of arms. These were not created until 1825 in Jena as painting on couleur pipes. The shape is that of a company coat of arms consisting of the shield with helmet, helmet ornament (usually ostrich feathers ) and helmet cover. Here the student heraldry is only used for the shields, so that the ostrich feathers, although arranged like vertical student colors, are read according to general heraldry, i.e. from left to right by the viewer.

See also

- Funeral heraldry

- Paraheraldry

- List of coats of arms of German states , List of flags of German federal states

- Flags and coats of arms of the countries of Austria

literature

- Milan boys : heraldry. Albatros, Prague 1987.

- Václav Vok Filip: Introduction to Heraldry (= basic historical sciences in individual representations. Volume 3). Steiner, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 978-3-515-07559-6 .

- Franz Gall : Austrian heraldry. Handbook of coat of arms science. 3rd unchanged edition. Böhlau / Vienna et al. 1996, ISBN 3-205-98646-6 .

- Adolf Matthias Hildebrandt (Ed.): Wappenfibel. Handbook of Heraldry. 19th, improved and enlarged edition. Degener, Neustadt an der Aisch 1998, ISBN 3-7686-7014-7 .

- Walter Leonhard : The great book of heraldic art. Development, elements, motifs, design. Bechtermünz-Verlag, Augsburg 2002, ISBN 3-8289-0768-7 .

- Ottfried Neubecker , JP Brooke-Little: Heraldry. Their origin, meaning and value. Orbis, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-572-01344-5 .

- Ottfried Neubecker: Heraldry. Special edition. Bassermann, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-8094-2089-7 .

- Gert Oswald : Lexicon of Heraldry. Bibliographaphisches Institut, Mannheim et al. 1985, ISBN 3-411-02149-7 .

- Georg Scheibelreiter : Heraldry (= Oldenbourg historical auxiliary sciences. Volume 1) Oldenbourg / Vienna et al. 2006, ISBN 3-486-57751-4 .

- Carl Alexander von Volborth : Heraldry from around the world in colors. From the beginning to the present. Universitas-Verlag, Berlin 1972 (original title: Alverdens heraldik in farver ).

- Hugo Gerard Ströhl : Heraldic Atlas. Stuttgart 1899 (reprint: Edizioni Orsini De Marzo, Milan 2010, ISBN 978-88-7531-074-5 ).

- Eduard von Sacken : Heraldry - basics of heraldry. Verlagbuchhandlung JJWeber, Leipzig 1899. 6th edition, revised by Moritz von Weittenhiller; Reprint Verlag, Leipzig 2012, ISBN 978-3-8262-3040-0 .

- Ludwig Bieber, Eckhart Henning: coat of arms. Handbook of Heraldry. 20th, revised and redesigned edition of AM Hildebrandt's coat of arms primer. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-412-50372-7 .

Web links

- Germany

- Rules of German Heraldry by Dr. Bernhard Peter

- HEROLD Association, Berlin (German coat of arms)

- Association "Zum Kleeblatt", Hanover (Lower Saxony coat of arms)

- Heraldic collections

- Collection of coat of arms photos with explanations, place registers , name register provided by Dr. Bernhard Peter

- Largest collection of coats of arms of municipalities and regional authorities from all over the world (English)

- WappenWiki - English-language collection of medieval and early modern personal and sovereign coats of arms

- Coats of arms collection with over 10,000 family coats of arms of Switzerland chgh.net

- French page with thousands of heraldic representations in a modular structure, geographical index, name index and, above all, many graphically processed medieval heraldic scrolls

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Diem : From Herolden and Wappen austria-forum.org

- ↑ Heraldry hgw.geschichte.uni-muenchen.de. Quote: “Coat of arms. They represent the subject of research in heraldry. Heraldry is understood as the doctrine of coat of arms law, of coat of arms representations and of the history of the coat of arms. "

- ^ Kümper, Hiram: Materialwissenschaft Mediävistik: an introduction to the historical auxiliary sciences . UTB, Paderborn 2014, ISBN 978-3-8252-8605-7 , p. 294 .

- ^ Duden online: Heraldry

- ↑ Duden online: Heraldskunst

- ^ Lit .: Leonhardt: Wappenkunst. Here coats of arms are shown in large numbers and in a "classic-modern" style.