Music fairy tale

As a musical fairy tale musical settings of fairy tales are primarily materials referred. The term is also used for fairy tales that are about music. In some cases both characteristics apply when a musical fairy tale is set to music.

Setting of fairy tales to music

Music fairy tales are not a separate genre of music in the narrower sense, but a descriptive term for setting folk or art fairy tales and other fairytale-like subjects to music. They can be found in different genres and musical forms such as the classical and romantic fairy tale opera , the Singspiel , the fairy tale cantata , as ballet music , fantasy and symphonic poetry . New compositional forms have also been created, especially with the intention of creating sophisticated music for children, in which music and narration alternate, as in the well-known work Peter and the Wolf . The modern works from the field of rock and pop music are also known, such as the music fairy tale by Rolf Zuckowski , Tabaluga with Peter Maffay and the music fairy tale Cloud 7 by Stefan Waggershausen .

With regard to the materials used, a distinction can be made between the fairy tale genres folk tales , art fairy tales and fairytale-like fabrics created especially for the composition . Sometimes musical fairy tales were used to introduce children to demanding musical works, such as Hansel and Gretel , which was also known as children's opera . The suitability for this depends on the respective material, the musical composition, the form of performance and the age of the children. The above-mentioned rock and pop music fairy tales and works that were explicitly composed in such a way that they can also be performed by children, such as the children's opera Brundibár by the German-Czech composer Hans Krása , which he composed in 1938 and which he wrote in 1941 , are clearly aimed at children Jewish children's home in Prague. Other fairy tale singing games from the educational or therapeutic context come from Ingo Bredenbach , Eberhard Werdin and Paul Nordoff . Materials that can be assigned to the genre of legend and saga , such as Sadko , The fairy tale of the beautiful Melusine or The Flying Dutchman and many other subjects, especially the great operas of the romantic era, must be distinguished from the musical fairy tales . The Mozart opera Die Zauberflöte occupies a special position , which is available in a multitude of different versions, transformations and modes of performance and which enables different levels of understanding.

Settings of folk tales

- La Cenerentola (1817), opera by Gioachino Rossini based on the fairy tale Cinderella .

- Sleeping Beauty Bride (1867), romantic magic opera by Viktor Nessler based on the fairy tale Sleeping Beauty .

- Das klagende Lied (1880), fairy tale cantata by Gustav Mahler based on the two fairy tales Das klagende Lied and The singing bone .

- Hansel and Gretel (1893), children's opera by Engelbert Humperdinck , libretto by Adelheid and Hermann Wette (previously also as a Liederspiel and Singspiel) based on the fairy tale Hansel and Gretel .

- The Seven Geislein (1895), Singspiel by Engelbert Humperdinck, libretto by Adelheid Wette based on the fairy tale The Wolf and the Seven Young Goats .

- Cinderella, (Ballet) (1901), ballet by Johann Strauss based on the fairy tale Cinderella .

- Sleeping Beauty (1902), opera by Engelbert Humperdinck, libretto by Elisabeth Ebeling and Bertha Filhés based on the fairy tale Sleeping Beauty .

- Puss in Boots (1913), children's opera by César Cui based on the Grimm fairy tale Puss in Boots .

- La bella addormentata nel bosco (1922), music fairy tale by Ottorino Respighi based on the fairy tale Sleeping Beauty based on Charles Perrault .

- Soluschka (1940–1944), ballet by Sergei Prokofjew based on the fairy tale Cinderella (Cinderella) .

- Die Kluge (1943), opera by Carl Orff based on Grimm's fairy tale The Clever Farmer's Daughter .

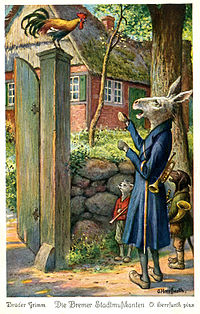

- Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten (1950), Opera buffa by Richard Mohaupt based on the fairy tale Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten .

- Der Fischer und sine Fru (1951), musical-scenic play for amateur ensemble, op. 39 by Eberhard Werdin.

- The Hedgehog as Bridegroom (1951), opera by Cesar Bresgen based on the Grimm fairy tale Hans mein Igel , libretto by Ludwig Strecker the Younger .

- The Three Bears (1966), fairy tale song game by Paul Nordoff based on the Grimm fairy tale Goldilocks and the Three Bears by Robert Southey , texts by Clive Robbins.

- Pif Paf Poltrie (1969), Singspiel by Paul Nordoff based on the Grimm fairy tale Die Schöne Katrinelje and Pif Paf Poltrie .

- Rales Musikmärchen , series about the Grimm fairy tales The Bremen Town Musicians, Frau Holle , The Frog King , King Drosselbart by Rolf Zuckowski.

- Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten, a musical fairy tale for piano four hands and speaker (2010), by Oliver Kolb.

Settings of art fairy tales

- The Nutcracker (1892), ballet by Peter Tchaikovsky based on the fairy tale Nutcracker and Mouse King by ETA Hoffmann .

- The Magic Word (1888), Singspiel by Josef Gabriel Rheinberger based on the fairy tale Kalif Storch by Wilhelm Hauff .

- Der Rubin (1893), opera by Eugen d'Albert based on the fairy tale Der Rubin by Friedrich Hebbel .

- Den lille pige med svovlstikkerne (1897), opera by August Enna based on the fairy tale The little girl with the sulfur sticks by Hans Christian Andersen .

- Königskinder (1897), fairytale opera by Engelbert Humperdinck based on the fairy tale Königskinder by Elsa Bernstein .

- The Mermaid (1905), fantasy for orchestra by Alexander von Zemlinsky (1902/03; premiered Vienna 1905) based on the fairy tale The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen.

- Le rossignol (1914), opera by Igor Stravinsky based on the fairy tale The Emperor's Nightingale by Hans Christian Andersen.

- Der Zwerg (1922), opera by Alexander Zemlinsky based on the fairy tale The Birthday of the Infanta by Oscar Wilde .

- The Princess and the Pea (1927/1928), children's opera by Ernst Toch based on the fairy tale The Princess and the Pea by Hans Christian Andersen.

- L'usignolo dell'imperatore (1959, revised 1970), ballet pantomime by Hans Werner Henze based on the fairy tale The Emperor's Nightingale by Hans Christian Andersen, libretto by Giulio Di Majo.

- Josa with the Magic Fiddle (1970), string quartet by Reinhard Ohse based on the fairy tale of the same name by Janosch .

- De Nachtegaal (1998), musical fairy tale by Theo Loevendie based on the fairy tale The Emperor's Nightingale by Hans Christian Andersen.

- The girl with the sulfur woods (1997), opera by Helmut Lachenmann based on the fairy tale The little girl with the sulfur woods by Hans Christian Andersen.

- Kalif Storch (2005), fairy tale song game by Ingo Bredenbach based on the fairy tale Kalif Storch by Wilhelm Hauff .

- The ugly duckling (2004), fairy tale opera by Vivienne Olive based on the fairy tale The ugly duckling by Hans Christian Andersen, libretto Doris Dörrie .

- Das Sternenkind (2005), fairy tale opera by Hans-André Stamm based on the fairy tale Das Sternenkind by Oscar Wilde.

- Lygtemaend I Byen (German will- o'-the-wisps in the city) (2005), fairy tale cantata by Per Nørgård based on the fairy tale The will-o'-the-wisps are in the city, said Hans Christian Anderson's moor woman .

- The Emperor's New Clothes (2007), a fairy tale based on the fairy tale The Emperor's New Clothes by Hans Christian Andersen.

- The minstrel (2010), musical tale by Ib Hausmann and Nanna Koch based on the fairy tale The minstrel by Selma Lagerlöf .

Compositions of fairytale fabrics

- Die Zauberflöte (1791), opera or singspiel by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder .

- Kaspar, the bassoonist, or: Die Zauberzither (1791), Singspiel by Wenzel Müller , libretto by Joachim Perinet .

- Once upon a time ... (opera) (1900), fairy tale opera by Alexander von Zemlinsky , libretto by Maximilian Singer based on Holger Drachmann .

- Königskinder (1908–1910), fairy tale opera by Engelbert Humperdinck, libretto by Elsa Bernstein .

- L'enfant et les sortilèges (Eng. The Child and the Magic Spook ) (1925), opera by Maurice Ravel , libretto by Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette .

- Die Zaubergeige (1935), opera by Werner Egk based on a puppet play by Franz Graf von Pocci .

- Peter and the Wolf (1936), musical fairy tale by Sergei Prokofjew , who also wrote the text himself. Numerous other arrangements see p. Main Products.

- Brundibár (1941), children's opera by Hans Krása, libretto by Adolf Hoffmeister.

- Das Traumfresserchen (1991), Singspiel by Wilfried Hiller based on the fairy tale of the same name by Michael Ende .

- Tabaluga (1993–2015), rock fairy tale in several episodes by Rolf Zuckowski with Peter Maffay about a story by Helme Heine , texts by Gregor Rottschalk , continuation: Tabaluga & Lilli (1993/1994), musical.

- Cloud 7 (2000), music fairy tale with Stefan Waggershausen, Nena , Die Prinzen , Michael Schanze , Erste Allgemeine Verunsicherung , Laura, The 3rd Generation , Ingolf Lück and Loona .

Fairy tales about music

Fairy tales about music can be found scattered in many fairy tale collections, in folk and art fairy tales and in the various languages and cultures. An accumulation of fairy tales with music can be found in the fairy tales of the Sinti and Roma and in the fairy tales (p. 166). The music can represent the main strand of the narrative, but it can also simply be the protagonist's job or only appear in individual scenes. Myths about music are to be distinguished from fairy tales, such as B. the Greek myths Orpheus , Pan and Syrinx and sagas and legends that are about music or musicians.

Music fairy tale collections

In 1984 the first German-language compilation of musical fairy tales was published under the title Where the flute sounds , edited by Johann Friedrich Konrad. It contains some European magical tales such as As the Irish tales O'Donoghues bagpipes and the Polish fairy tales The violin, which fell from the sky and some art tales as The artificial organ of Richard von Volkmann-Leander . Under the title Musikmärchen set of fairy tales researchers Leander Petzoldt 1994 for the series Tales of the World , another collection of 28 European folk tales before, in which music plays a central role. It focuses on German-language magical fairy tales, many from the fairy tale collections of the Brothers Grimm and Ludwig Bechstein , but also contains magical fairy tales from Ireland , Slovakia , Greece , Sicily and a Roma fairy tale. Another collection appeared in 2001 under the title Bell, Drum, Magic Violin. Music fairy tales from all over the world , edited by Dorothée Kreusch Jacob, which contains not only European fairy tales but also those from Mexico , Japan , China and Africa . In addition to folk tales, some art fairy tales are also included. A list of over 300 European folk tales in which music occurs can be found in Rosemarie Tüpker's book Music in Fairy Tales (pp. 292–308).

Some non-European fairy tales that deal with music have also appeared in German. B. the Japanese fairy tale the little bell , which makes all people who hear it happy, and the Buddhist fairy tale Guttila, the musician , in which the student of a vina master tries to outdo him. The master and bodhisattva , however, receives supernatural help, can now make beautiful tones sound even with torn strings, which the student does not succeed, and through his excellent play also learns the world of gods and the principle of karma . In the collection of fairy tales from Burma there is the fairy tale The Boy with the Harp , in which a boy first supports his mother with his musical skills until he is held on the islands by the gods with a wicked trick, because it is based on beauty don't want to miss out on playing.

Motivation

A fairy tale motif that occurs frequently in the entire European narrative space is the musical instrument given as a reward, which has the magic power to make people dance like in the Grimm fairy tale The Dearest Roland . The instruments given by higher beings or given by the devil are often a flute or violin , but they can also be a harp , a bagpipe or a clarinet (pp. 177–188). The phrase “dance to your tune” refers to this idea and can also be found as a fairy tale title in Theodor Vernaleken's collection of children's and household tales : They dance to the tune .

Other instruments and the song that often resounds from them become witnesses to a crime that is mostly long past, as is also the case in the two fairy tales that were the model for Mahler's fairy tale cantata Das klagende Lied . This motif can also be found throughout the European narrative space. Often the instruments are made from a part of the human body that fell victim to the crime, such as a bone flute . In the fairy tale Von dem Machandelboom , it is a singing bird that betrays the crime (pp. 251–263).

Music can touch you emotionally, as in the Roma fairy tale The Creation of the Violin . Further examples are the Austrian fairy tale Das Ewige Lied and the Russian fairy tale Der Zaubermusikant . (Pp. 193–204) Music can become an object of longing and trigger further developments, such as in the fairy tales The Singing Broommaker's Daughter from Mecklenburg or the Roman story The King and Poor Čhavo (p. 225). This can also have a dangerous form, as in the many fairy tales in which the heroes of mermaids or fairies are torn to ruin by their beautiful music (p. 239). Music connects the world of people with the other worlds, as is told in many fairy tales or in the Grimm fairy tale Dat Erdmänneken . Sometimes the music then also stands for the foreign, which has to be disposed of, as in the Grimm fairy tale The Little Bagpiper . Often this is connected with the motif of the changeling . Some fairy tales also tell of the shepherds' ability through their flute playing to keep animals together or to appease dangerous animals, such as B. in the French fairy tale The Night Adventures of a Musician (p. 199). Fairy tales can be closely linked to the identity of the hero, as the fairy tales tell, in which the protagonist first finds himself through his instrument, as in Grimm's fairy tales Das Eselein or simply the profession or earning money of the (then mostly rather poor ) Be protagonists.

Folk tales (selection)

- The noisy donkey

- The plaintive song

- Dat meerkats

- The devil's sooty brother

- The Jew in the Thorn

- The little bagpiper

- The singing bone

- The drummer

- The strange minstrel

- The Bremen Town Musicians

- The creation of the violin

- The gifts of the little people

- Hans my hedgehog

- From the machandel boom

Art fairy tales (selection)

- Josa with Janosch's magic fiddle

- The swineherd

- The heavenly music by Richard von Volkmann-Leander

- The Nightingale

- The sunken bell

- Flute dream , fairy tale by Hermann Hesse

- Kaito , fairy tale novel by Hans Kruppa

- Stone and Flute , fairy tale novel by Hans Bemmann

Individual evidence

- ↑ Oliver Kolb, Publications

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Rosemarie Tüpker Music in Fairy Tales . Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden 2011

- ↑ see: Lutz Röhrich : Musikmythen . The music in the past and present factual part, 2nd edition, Vol. 6, 2, 1426-1440. rework. Edition, ed. by Ludwig Finscher Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel a. a. 1997

- ^ Johann Friedrich Konrad: Where the flute sounds. Fairy tales of the peoples of music, dance and play. Gütersloher publishing house, Güterslohn 1984

- ↑ Leander Petzoldt (Hrsg.): Musikmärchen: Märchen der Welt. Fischer-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1994

- ↑ a b Dorothée Kreusch-Jacob (Ed.): Little bell, drum, magic violin: musical fairy tales from all over the world. Schott Verlag, Mainz 2001

- ↑ Else Lüders (ed.): Buddhist fairy tales from ancient India. Eugen Diederischs Verlag, Düsseldorf / Cologne 1979 ISBN 3-424-00247-X

- ↑ Jan-Philipp Sendker : The secret of the old monk. Fairy tales and fables from Burma. Blessing-Verlag, Munich 1917, pp. 163-167. ISBN 978-3-89667-581-1

- ↑ They dance to his tune. Full text

- ↑ The Magic Musician, full text

literature

- Erika Zwanzig: Fairy tales, myths, sagas, legends set to music. Western music and literature from the beginning to the present with a brief summary of the topics set to music in AZ , 2 volumes, Merkel-Verlag, Erlangen 1992

- Leopold Schmidt : On the history of the fairy tale opera . German university publications, old series, 1895 (microfiche: Hänsel-Hohenhausen, Egelsbach 1995). ISBN 3-8267-3140-9

- Matthias Herrmann , Vitus Froesch (ed.): Fairy tale opera - a European phenomenon. Series of publications by the Dresden University of Music, Sandstein-Verlag, Dresden 2007 ISBN 978-3-940319-14-2

- Gordon Kampe : Topoi, gestures, atmospheres - fairytale opera in the 20th century. Pfau-Verlag, Saarbrücken 2012 ISBN 978-3-89727-446-4