Skibo Castle

Skibo Castle ( Scottish Gaelic Caisteal Sgìobail ) is a castle in the style of the Scottish Baronial about six kilometers west of Dornoch in the Scottish Highlands . At the end of the 19th / beginning of the 20th century, tycoon Andrew Carnegie had the building built by redesigning and expanding a mansion that had been built around 25 years earlier . Carnegie's family owned the castle and large estate until the 1980s, before Derek Holt bought it in 1982. After restorations and modernizations for several million pounds, Holt sold in 1990Peter de Savary , who made it the seat of the exclusive Carnegie Club and in 2003 sold it to a society of members of this club.

The castle stands together with its terraced garden since March 4, 2003 as Listed Building category A under monument protection . The large palace park was also included in the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes on July 1, 1987 .

history

Beginnings in the Middle Ages

The castle dates back to a fortification in the 9th or 10th century. It may have been built by the Vikings , as the name "Skibo" is probably of Old Norse origin. According to William J. Watson , “Skibo” is the Anglicization of the Scottish Gaelic “Sgiobal”, which in turn comes from an Old Norse name that means either “firewood store” or “home of Skithi”. The land around Skibo was first mentioned in 1186 when King William the Lion gave it as a fief to Hugh Freskin (also written Hugo and Freskyn). In turn, there was an after-fief to his relative Gilbert de Moravia , who became Bishop of Caithness in 1222/1223 . During his tenure in "Schytherbolle", as Skibo was called at that time, a fortified castle was built on the remains of the old fortification , which served as one of the main episcopal residences until the 16th century. Hugh Freskin's son, William , became the first Earl of Sutherland and renewed the enfeoffment to the bishop. However, the bishopric and the Earl did not always agree on the ownership structure, because a dispute over it is recorded for 1275.

The Gray and MacKay families

In 1544 the MacKays took the castle, but in the following year the then bishop select Robert Stewart gave the complex to John Gray, who had previously been enfeoffed with a lot of land around Skibo by John Gordon, 11th Earl of Sutherland . At that time, however, according to a document from the 16th century, the castle was in a dilapidated condition. During the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in 1650 the Covenanters held Royalist James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose , defeated in the Battle of Carbisdale , at Skibo Castle before he was taken to Edinburgh for his execution . In the 18th century, the then owner, another John Gray, had to sell Skibo Castle to pay off his debts. In this way the plant came to Gray's attorney Sir Patrick Dowall in 1744, but he had neither the money nor the motivation to clean up the shabby property. In 1751 he was inherited by his nephew, George MacKay , a son of the third Lord Reay . In contrast to his uncle, he took great care of his new property. So he let the courts of the tenants repaired and cleared land reforestation . On the other hand, he did not have the old castle made habitable again, but instead had two new buildings built to the south and west of the old keep as accommodation for his family and servants. For the numerous improvements and new buildings, MacKay had to go into debt and was ultimately forced to sell Skibo in 1756. The new owner was William Gray, a descendant of the previous owners who had made a fortune with sugar plantations in Jamaica . He continued the improvements started by the previous owner by cultivating fallow farmland and building new homes for additional tenants. Gray also had rebuilding plans for the old castle, but he died in 1760 before he could actually carry them out. His widow Janet Sutherland initially continued her husband's work. The castle was given a new slate roof - the first building in Sutherland next to Dornoch Cathedral . However, London was much more appealing to her as a place of residence, and so she left Skibo forever in the early 1760s and left the property to itself again.

New bloom under the Dempster family

After Janet's death in 1785, it turned out that William Gray had also died heavily in debt and that the debts had not been paid during his lifetime or those of his widow. The High Court in Edinburgh therefore decided in 1780 that Skibo was to be regarded as bankruptcy and placed it under receivership . The Court of Session initially became the official owner. He sold the property in 1786 for 11,500 pounds to the MPs George Dempster of Dunnichen . He not only modernized and expanded the property, but also enlarged the property by purchasing Pulrossie and Overskibo. The overgrown palace gardens were also restored under him. Because Dempster's marriage had remained childless, he wanted to leave Skibo to his brother's only son, but he died in April 1801. Only a month later, Dempster learned that his brother John had been killed in a shipwreck in the Indian Ocean in October 1800, and so transferred he Skibo Castle Harriet Milton, an illegitimate daughter of his late brother who was married to Colonel William Soper. Her family subsequently called themselves Soper-Dempster. The castle was inherited by the couple's son, George Soper-Dempster, who also had no children and in 1866 sold the property to an Australian named Chirnside. At that time, the keep the plant was now a ruin expire.

New construction and renovation under Evan Charles Sutherland-Walker

However, the new owner did not keep Skibo very long. After only six years, he sold the castle and 20,000 acres of land in 1872 for 130,000 pounds to Evan Charles Sutherland-Walker. The new lord of the castle again made changes and modernizations to the property. So he built a new farmyard, erected additional stables and also had the foundation stone laid for today's castle park. Some of the greenhouses still preserved to the north of the castle and probably the east lodge also come from him. Sutherland-Walker finally took care of the keep ruin. In their place he had a representative, neo-Gothic mansion built by the Glasgow architects Clarke & Bell around 1875 . It is not yet clear whether this was done using medieval building fabric. Like MacKay and Gray before him, Evan Charles Sutherland-Walker threw himself into large debts for the numerous changes on Skibo, which he could ultimately no longer pay. He went bankrupt , had to hand over the castle and the land belonging to it to a court-appointed trustee and leave Skibo. He spent his twilight years in Inverness.

A new lord of the castle from 1898: Andrew Carnegie

In 1898, American steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie bought the dilapidated property for £ 85,000. In previous years, he and his wife Louise had spent every summer in Scotland, living at Cluny Castle . But this property was not for sale, so Carnegie decided to purchase Skibo because it had two scenic features that he required: an extensive view of the ocean and a stream where he could fish for trout . Only Skibo could not offer the waterfall , which was also requested , but instead a large property that promised to be profitable if managed according to modern criteria. Under the American, the property was completely redesigned. He had the two buildings erected by George MacKay completely demolished and the mansion built under Evan Charles Sutherland-Walker was converted into a large country palace on June 23, 1899. The plans for the new building came from the Inverness-based architects Ross & Macbeth, who worked with Louise Carnegie on the planning and design. The new lord of the castle delegated all tasks related to the renovation to his wife. The castle became one of the last great houses in the style of the Scottish Baronials, which was actually out of fashion again by the end of the 19th century. The 100 rooms of the new building were equipped with the latest technology and offered an extremely high level of comfort. So Skibo Castle was the first building in Scotland, in which an elevator company Otis was installed. Carnegie was not limited in his remodeling to the castle building, but had the entire property changed. For the many technical innovations on the site of its own water and electricity supply has been installed as well as numerous new buildings erected, such as new tenant houses, one indoor pool , a dairy , a coach house, sheds , poultry houses and a stud farm with 20 horses. Andrew Carnegie had the farmyard northeast of the castle changed and expanded.

The new owner also radically changed the area around the castle. He had the main driveway to the castle relocated to the west and the west lodge built at its starting point as an apartment for his chief forester. In addition, three artificial lochs were created under him : Loch Evelix as a fishing pond (named after the Evelix tributary), Margaret's Loch and Lake Louise, one of the few lakes in Scotland called "Lake" instead of "Loch". On the banks of the Dornoch Firth, a dock for Carnegies private yacht was built and a 9-hole golf course nearby . In 1904, Andrew Carnegie hired the landscape architect Thomas Mason to redesign the gardens that were directly adjacent to the palace building . Today's terrace garden and the avenue between the West Lodge and the castle go back to him. At the same time, Carnegie had MacKenzie & Moncur build various greenhouses and an orangery . All work was finished around 1905 and totaled around two million pounds.

Until the outbreak of World War I , the Carnegies spent part of the summer and autumn at Skibo Castle every year, where they received and entertained friends, acquaintances and business partners from the start. The societies were mostly mixed: members of the nobility sat next to intellectuals from the bourgeoisie, international politicians or members of Andrew Carnegie's Scottish relatives during the events. The illustrious guests on Skibo included Woodrow Wilson , Theodore Roosevelt , King Edward VII of England , Herbert Henry Asquith , Helen Keller , Rudyard Kipling and members of the Vanderbilt and Rockefeller families . During Carnegie's time as lord of the castle, a custom arose that is still practiced today: guests at Skibo Castle are woken up every morning at eight o'clock by the music of a bagpiper.

The Carnegie Family (1919 to 1982)

After Carnegie's death in 1919, his widow Louise came regularly to Skibo Castle until 1934 to spend a few months of the year there. On July 27, 1938, the marriage of her eldest granddaughter Louise to the Scottish Gordon Thompson was celebrated there as part of a party with 1000 guests. During the Second World War , the area of the former golf course was used for growing grain. After Louise's death in 1946, Carnegie's only child, daughter Margaret (married Miller), inherited the property. She also visited the castle regularly, although as the owner she was faced with increasing maintenance costs and taxes. In order to keep Skibo Castle and its agriculture and forestry reasonably profitable, they had to sell part of the large land holdings in the 1950 / 1960s. Margaret Carnegie-Miller was also the one who opened the estate's garden and park to the public two days a year since the 1960s. However, this was not the case when the English Queen Elizabeth II and her husband Prince Philip were guests at the palace for lunch in June 1964. During the time when Margaret was the mistress of the castle, the castle and its garden were placed under protection as a Listed Building - initially Category B - on March 18, 1971. To preserve Skibo Castle as a unit and in memory of her father Andrew, she planned to build Skibo To be handed over to the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust in 1980. However, the foundation's statutes forbade accepting the deficit property as a gift, as it was foreseeable that it would not be self-sufficient and that it was too expensive to maintain. Therefore they wanted to sell Skibo Castle and let the proceeds go to the trust. A buyer was finally found in 1982 in entrepreneur Derek Holt, who allegedly offered £ 2.5 million for the property.

Todays use

Holt had the castle renovated and various buildings of the extensive property renewed, which he and his family used as a residence. In 1989 he sold the property to the Globe Investment Trust, which in July 1990 sold it to the English entrepreneur Peter de Savary. De Savary had it renovated and modernized extensively for £ 30 million over the next three years so that the castle was used as a luxury hotel for members of the exclusive Carnegie Club from 1993 onwards. On the night of December 9th to 10th, the main building was badly damaged by fire, but the damage was quickly repaired. As in Andrew Carnegie's time, numerous personalities from politics, business and entertainment have visited the castle since it opened. The guests included, for example, the former American President Bill Clinton and the actors Sean Connery , Michael Douglas and Jack Nicholson . The British singer Robbie Williams celebrates his 30th birthday there, and Skibo Castle is also very popular as a wedding venue. Not only did Madonna and Guy Ritchie say yes there in December 2000, Ewan McGregor , Ashley Judd and the golfer Sam Torrance also chose Skibo as their wedding venue. When one of the investors, Westbrook Global Partners, withdrew from the business in 2003, de Savary was forced to sell Skibo Castle. He found a buyer in a group of investors consisting of members of the Carnegie Club, who have continued the club since then, although Skibo Castle made losses until 2013. After the takeover, renovations followed. The repair of the golf clubhouse and the lodges on the castle grounds cost two million pounds. A further eight million pounds were earmarked for work on the palace building and the restoration of the Victorian swimming pool.

description

location

The property is six kilometers west of Dornoch in the Northern Highlands, about an hour's drive from Inverness . The castle stands on a terrace in the middle of the Dornoch Firth National Scenic Area on the north bank of the Dornoch Firth and overlooks the inlet. The castle area, which is now 7,500 acres, is largely enclosed by dry stone walls. In the north it is bounded by the A949 , in the south lies the Dornoch Firth. The eastern border of the property is the A9 .

Castle building

The large castle building was built from hewn sandstone from a local quarry . Its four and five storeys rise on an irregular floor plan. The style of the Scottish Baronial is reflected in a crenellated wreath , numerous square and round turrets as well as stepped gables and a rich sculptural decoration . The oldest part of the current building dates from around 1875, but the majority is younger and is dated to the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. In front of the south side there is a large, elongated terrace , which is supported by strong retaining walls and has round bastions . The terrace walls, the castle garden adjoining it to the south, the castle building and some greenhouses were upgraded as a protected building ensemble from category B (buildings of regional importance) to category A (buildings of national or international importance) on March 4, 2003 . A flag that combines the Union Jack and the American stars and stripes flies on the roof . It goes back to Andrew Carnegie, who wanted to express his attachment to both states.

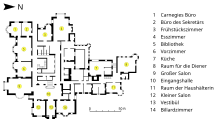

The main entrance of the house is on the east side. A car driveway designed as a portico is in front of it. The entrance leads to a vestibule that leads to a large entrance hall with oak paneling , parquet floors and a monumental fireplace. A large wooden staircase with elaborate carvings leads from there to the upper floors. The stairwell has five stained glass windows depicting themes from the life of Andrew Carnegie and the history of the castle. Sankt Gilbert von Dornoch is shown in the center with the year 1235. To the right of it is - together with the year 946 - a portrait of the Viking Sigurd and Carnegie's birthplace as well as the small ship Wiscasset , with which Carnegie and his parents sailed from Scotland to America in 1848. The windows on the left show the Marquis of Montrose with the year 1650 and the great ocean liner that Carnegie took back to Scotland; above it the year 1898. An organ is installed next to the staircase, which was installed there in 1904 by Andrew Carnegie.

The 21 bedrooms of the castle all have their own bathrooms, some of which are still equipped with the original mosaic floors. The very low door handles in the building are also original. They remind you that the client was a very short man. Much of the furniture also dates back to the time when Andrew Carnegie was lord of the castle, for example the library with its stucco ceiling and 2500 books purchased by the steel magnate. The fireplace in the paneled castle library has an oak casing richly decorated with carvings . On its ledge is a carving in the form of an open book. One of Andrew Carnegie's favorite lines can be read in it: He that cannot reason is a fool. He that will not is a bigot. He that dare not is a slave. (German: The one who cannot think is a fool. The one who will not think is a zealot. The one who does not dare to think is a slave.) Other pieces of Edwardian furnishings and fittings of the house, which in the course of which had been sold during the period have now been repurchased where possible.

Further buildings on the palace area

Cottages and Lodges

In addition to a total of eleven lodges, there are cottages and courtyards spread all over the property , the majority of which were built by Andrew Carnegie for the tenants of Skibo. One of them is the formerly U-shaped estate, which was converted into the golf course clubhouse in 1993. The house may date back to the 1870s when Evan Charles Sutherland-Walker was Lord of Skibo Castle.

The former gardener's house from 1880 stands on a site where there were previously dog kennels . In the 1980s the house was changed and the previous stepped gable was replaced by the current gable shape . The slate covering of the roofs is more recent.

The two-storey Ospisdale Lodge was created by combining two detached houses standing next to each other, which served as the property's electricity plant and telephone exchange before the building was used as a garage. It dates from the early 20th century and is possibly a design by the architects Ross & Macbeth. The building with two-axis extensions on the north side has a slate roof and stepped gable. Its two dormitories have rich sculptural decoration. The lodge now serves as a sports hall and spa area . It has been a listed building in Category A since March 7, 1984.

There are three more lodges at the entrances to the palace area on the west, north and east sides. Like the Ospisdale Lodge, the West Lodge has been a listed monument (category B) since March 7, 1984. It was built in 1907 based on designs by Ross & Macbeth. The house with brickwork made of humpback blocks has an L-shaped floor plan, with the north wing having two storeys and the east wing one. In the corner of the two wings there is a three-storey stair tower with a crenellated crown at the top. The east wing has a stepped gable, which is crowned by a stone eagle sculpture. The building has been used for residential purposes again since the 1990s. The western gate system consists of a two-winged gate between massive, rusticated round pillars . This is followed on both sides by two narrower pedestrian gateways with lattice gates, which are flanked by pillars like the main gate.

The east gate is less elaborately designed than its western counterpart, but has a similar shape. It was restored in 2011. The grid of the north gate no longer exists, only a pedestrian gate next to it has been preserved. The gate system presumably dates from the first half of the 19th century, the north lodge in the immediate vicinity is more recent.

Swimming pool

The Victorian swimming pool, which has been protected as a Category B Listed Building since March 7, 1984, is located about 180 meters southwest of the castle building. The building was built under Andrew Carnegie around the turn of the century and was previously filled with sea water. As the castle building was equipped with the latest technology at the time, the 24 × 9 meter swimming pool could be heated. In 2010 the building and pool were restored and upgraded for £ 3.5 million. Since then, the swimming pool has had dimensions of 21 × 10 meters. The building has numerous arched windows and a steel and glass construction as the roof. Its southern end is semicircular, at the northern end a building with changing facilities is in front of it. At the time when the Carnegie family owned the castle, the pool could be covered with a wooden floor and the swimming pool could be used as a ballroom .

Other buildings

On the southern edge of Loch Ospisdale, the Ospisdale Bridge crosses its outflow into the Dornoch Firth. The structure, which dates back to the early 20th century, was built under Andrew Carnegie and also served as a weir . Sandstone was used as the building material for its six arches . The bridge has been listed as a category C individual monument since March 7, 1984.

One of the many farm buildings that Andrew Carnegie had built on the castle grounds was a dairy about 250 meters northeast of the main house and near the farm yard. It has been protected as a Category B Listed Building since March 7, 1984. The architecturally most striking part is its single-storey west wing with a heptagonal roof at the west end. The eaves of the bent roof with tile covering rests on natural wooden pillars. The resulting roof overhang forms a narrow veranda . Some windows still have their original lead glazing with Art Nouveau motifs . Inside the building, the decorative wall and ceiling tiles as well as marble work surfaces have been preserved.

Castle park and garden

The property includes a 502 hectare large landscaped park . It extends from the settlement of Ospisdale in the west to Clashmore in the east. It has four holes: Loch Ospisdale, Loch Evelix on the northern edge of an 18-hole golf course , Margaret's Loch and Lake Louise, which was named after Andrew Carnegie's wife. The park landscape is a habitat for numerous native bird species and a resting place for migratory birds . Some special trees grow in the landscaped garden, including a giant sequoia and an old parrotia . Some of the beech trees lining the access avenues to the castle are over 250 years old. In addition, there are areas with fruit trees and some forest areas with mixed forest in the park . The entire area has been listed in the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes since July 1, 1987 .

To the south and east of the palace building is the terraced palace garden, which already existed in 1878. A large part is designed as a walled garden (German: walled garden). Some sections of the quarry sandstone wall date back to the end of the 18th century or the early 19th century. The garden was redesigned in 1904 by Thomas Mason. For example, the staircase with baluster railing that connects the terraces of the garden and a heather garden on the edge of the staircase come from him. On the top terrace is an old sundial , the two deeper levels are at their northern borders of discounts hemmed. On the middle terrace, these plantings are located on the site of former greenhouses that were there until the 2000s. Exotic fruits have been grown there since Andrew Carnegie's time. They were just as old as those greenhouses that are still north of the castle today. However, these historic buildings by MacKenzie & Moncur are in a very poor condition and are therefore on the list for endangered monuments. On the lowest, mostly landscaped garden level is a formal rose garden , the beds of which are grouped around a circular water basin in the middle. One half of the eastern area of the walled garden is designed as an ornamental and the other half as a kitchen garden. In the north-east corner of this area there is a small, polygonal tower that may have served as a pavilion in the past , as such a tower has been handed down for the garden. Another summer house used to stand in the forest south of the castle. The former pigeon tower north of the main building no longer exists.

literature

- William Calder: The Estate and Castle of Skibo. Edinburgh, Albyn Press, 1949.

- Martin Coventry: The castles of Scotland. A comprehensive reference and gazetteer to more than 2000 castles. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh, Goblinshead 1997, ISBN 1-899874-10-0 , p. 300 ( online ).

- Peter Gray of Southfield: Skibo. Its lairds and history. Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier, Edinburgh 1906.

- Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. New York [u. a], Oxford University Press 1984, ISBN 0-19-503450-3 ( digitized ).

- Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. Moray, May 2013 ( PDF ; 1.24 MB).

- A Glimpse of Skibo Castle. In: Country Life in America. No. 1, February 1902, pp. 111-115.

Web links

- Website of the castle and the Carnegie Club

- Entry of the palace park in the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes (English)

- Entry of the castle in the national monument list Scotland (English)

- Entry on Skibo Castle in Canmore, Historic Environment Scotland database

- Video to the castle (English)

- Aerial video of the property

Footnotes

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Entry of the palace gardens in the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes , accessed on March 12, 2018.

- ^ William J. Watson: Scottish Place-name Papers. Steve Savage, London [u. a.] 2002, ISBN 1-904246-05-2 , pp. 40, 68, 234.

- ^ According to Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 10. Older publications, however, mention the year 1211 for the first documentary mention.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 10.

- ↑ a b Skibo Castle on rampantscotland.com , accessed March 12, 2018.

- ^ A b c Martin Coventry: The castles of Scotland. 1997, p. 300.

- ^ According to Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 15. According to other sources, the loan was not given until 1565.

- ↑ a b Entry on Skibo Castle in Canmore, Historic Environment Scotland's database, accessed on February 2, 2018.

- ↑ John Geddie: The royal palaces, historic castles and stately homes of Great Britain. Otto Schulze, Edinburgh 1913, p. 29.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 20.

- ^ A b Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 21.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 22.

- ^ John Evans: The Gentleman Usher: The Life & Times of George Dempster 1712-1818. Pen and Sword, Barnsley 2004, ISBN 1-84415-151-4 , p. 180 ( digitized ).

- ^ John Evans: The Gentleman Usher: The Life & Times of George Dempster 1712-1818. Pen and Sword, Barnsley 2004, ISBN 1-84415-151-4 , p. 181 ( digitized ).

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 29.

- ↑ a b c Information on the castle at scottish-places.info , accessed on February 13, 2018.

- ^ A b c Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 4.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 33.

- ↑ a b Information on the property on scottish-places.info , accessed on February 13, 2018.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 44.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 63.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 70.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 51.

- ↑ John Connachan-Holmes: Country Houses of Scotland. House of Lochar, Argyll 1995, ISBN 1-899863-00-1 , p. 111.

- ^ A b c John Thornhill: The story of Skibo, Andrew Carnegie's Scottish estate. In: Financial Times . Edition of September 19, 2014 ( online ).

- ↑ Did You Know? - Lakes in Scotland , accessed March 12, 2018.

- ^ Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 7.

- ↑ Alison Millington: Inside the 'millionaire's playground' members club in a Scottish castle, which costs £ 25,000 to join and has boasted guests like Madonna. on businessinsider.com, accessed March 12, 2018.

- ^ A b Sarah Royce-Greensill: Savoring the best of Scotland at spectacular Skibo Castle. In: The Telegraph . Edition of January 6, 2017 ( online ).

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 74.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 117.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 135.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 153.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 157.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 156.

- ↑ a b Entry of the castle on Scotland's National Monument List , accessed January 30, 2018.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, pp. 170-171.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall: Skibo. The story of the Scottish estate of Andrew Carnegie, from its Celtic origins to the present day. 1984, p. 180.

- ↑ Jessica Maxwell: Staying at Andy’s. In: Forbes . Edition July 7, 2007 ( online ).

- ↑ The information on the purchase price fluctuates between four and ten million pounds.

- ↑ a b c Greig Cameron: Losses at Skibo Castle widen to £ 1.2m as luxury resort sees its turnover fall to £ 8m. In: The Herald . Edition of September 25, 2013 ( online ).

- ^ Highland Skibo Castle is sold. In: The Scotsman . Edition of May 29, 2003 ( online ).

- ↑ Buyout 'will take Skibo to new heights'. In: The Scotsman. Edition of May 30, 2003 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Skibo says 'I don't' to £ 1m of business. In: The Scotsman. Edition of June 14, 2004 ( online ).

- ↑ a b John Connachan Holmes: Country Houses of Scotland. House of Lochar, Argyll 1995, ISBN 1-899863-00-1 , p. 110.

- ^ Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 13.

- ↑ Coordinate: 57 ° 52 ′ 33.8 ″ N , 4 ° 8 ′ 1.5 ″ W.

- ^ Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 16.

- ↑ Coordinate: 57 ° 52 ′ 18.7 ″ N , 4 ° 8 ′ 7.4 ″ W.

- ↑ a b Entry of Ospisdale Lodge on Scotland's National List of Monuments , accessed March 12, 2018.

- ↑ West Lodge: 57 ° 52 ′ 18.9 ″ N , 4 ° 10 ′ 27.6 ″ W , North Lodge: 57 ° 52 ′ 37.2 ″ N , 4 ° 8 ′ 0.5 ″ W , East - Lodge: 57 ° 52 ′ 25.7 ″ N , 4 ° 6 ′ 43.2 ″ W.

- ↑ Entry of the West Lodge and West Gate in the National Monument List of Scotland , accessed March 12, 2018.

- ^ Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 11.

- ↑ a b Entry of the swimming pool on the National Monument List of Scotland , accessed March 12, 2018.

- ↑ Coordinate: 57 ° 52 ′ 18.1 ″ N , 4 ° 8 ′ 5.8 ″ W.

- ↑ a b Information on the restoration project on the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland (RIAS) website , accessed February 15, 2018.

- ↑ Coordinate: 57 ° 52 ′ 13 ″ N , 4 ° 8 ′ 9.7 ″ W.

- ^ Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 22.

- ↑ Entry of the bridge on Scotland's National List of Monuments , accessed February 15, 2018.

- ↑ Coordinate: 57 ° 52 ′ 31.4 ″ N , 4 ° 7 ′ 50.5 ″ W.

- ↑ Entry of the dairy on Scotland's National Monument List , accessed February 15, 2018.

- ^ Annunciata Elwes: Skibo Castle: Carnegie's Highland paradise. In: Country Life . Edition of February 21, 2017 ( online ).

- ^ Andrew PK Wright: Historic environment audit of the Skibo Estate. Illustrated gazetteer. 2013, p. 6.

- ↑ Buildings at Risk Register for Scotland , accessed March 12, 2018.

Coordinates: 57 ° 52 '23.2 " N , 4 ° 7' 56.2" W.