Dakota Fanning and Mao Zedong: Difference between pages

Undid revision 245104027 by 69.138.64.175 (talk) see r |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Otheruses|Mao (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{Infobox actor |

|||

{{Chinese name|'''毛 (Mao)'''}} |

|||

| image = Dakota_Fanning_cropped.jpg |

|||

{{Infobox President |

|||

| caption = Fanning at the London premiere of ''War of the Worlds'', June 2005 |

|||

|name = '''毛泽东'''<br />Mao Zedong |

|||

| birthname = Hannah Dakota Fanning<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20050204/news_1c04dakota.html|title= 'Hide and Seek' star Fanning, at 10, already owns acting chops|accessdate= 2008-09-29|author= Colleen Long|date= 2005-02-04|publisher= [[San Diego Union-Tribune]]}}</ref> |

|||

|image = Mao Zedong.jpg|150px |

|||

| birthdate = {{birth date and age|1994|2|23}} |

|||

|nationality = [[People's Republic of China|Chinese]] |

|||

| birthplace = [[Conyers, Georgia]], [[U.S.A.]] |

|||

|religion = [[Atheist]] |

|||

| occupation = actress |

|||

|order = 1st [[Chairman of the Communist Party of China]] |

|||

| yearsactive = 2000 — present |

|||

|term_start = 1943 |

|||

| awards = '''[[BFCA Critics' Choice Award for Best Young Performer|Critics Choice Award for Best Younger Actress]]'''<br>2001 ''[[I Am Sam]]''<br>2005 ''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'' <br> '''[[Saturn Award for Best Performance by a Younger Actor|Saturn Award for Best Younger Actor]]'''<br>2005 ''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'' |

|||

|term_end = 1976 |

|||

|predecessor = [[Zhang Wentian]]<br>(as [[General Secretary of the Communist Party of China]]) |

|||

|successor = [[Hua Guofeng]] |

|||

|birth_date = {{birth date|df=yes|1893|12|26}} |

|||

|birth_place = [[Hunan]], [[Great Qing|Chinese Empire]] |

|||

|death_date = {{death date and age |df=yes|1976|9|9|1893|12|26}} |

|||

|death_place = [[Beijing]], [[People's Republic of China]] |

|||

|spouse = [[Yang Kaihui]] (1920–1930) <br /> [[He Zizhen]] (1930–1937) <br /> [[Jiang Qing]] (1939–1976) |

|||

|party = [[Communist Party of China]] |

|||

|vice_president = |

|||

|order2 = 1st [[President of the People's Republic of China]] |

|||

|term_start2 = September 27, 1954 |

|||

|term_end2 = December 1959 |

|||

|predecessor2 = Position Created |

|||

|successor2 = [[Liu Shaoqi]] |

|||

|order3 = 1st [[Central Military Commission of the People's Republic of China|Chairman of the Central Military Commission]] |

|||

|term_start3 = 1942 |

|||

|term_end3 = 1977 |

|||

|predecessor3 = Position Created |

|||

|successor3 = [[Hua Guofeng]] |

|||

|order4= 1st [[Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference|Chairman of the CPPCC]] |

|||

|term_start4= October 13, 1949 |

|||

|term_end4= 1964 |

|||

|predecessor4= Position Created |

|||

|successor4= [[Zhou Enlai]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{chinesetext}} |

|||

'''Mao Zedong''' {{Audio|Zh-Mao_Zedong.ogg|pronunciation}} ([[26 December]] [[1893]] – [[9 September]] [[1976]]) was a [[China|Chinese]] [[military]] and [[politics|political]] leader who led the [[Communist Party of China]] (CPC) to victory against the [[Kuomintang]] (KMT) in the [[Chinese Civil War]], and was the leader of the [[People’s Republic of China]] (PRC) from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976.Regarded as one of the most important figures in modern world history,<ref>{{cite web|work=The Oxford Companion to Politics of the World|url=http://www.oxfordreference.com/pages/samplep02|title=Mao Zedong|format=HTML|accessdate=2008-08-23}}</ref> and named by [[Time Magazine]] as one of the [[Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century|100 most influential]] people of the 20th century,<ref>[http://www.time.com/time/time100/leaders/profile/mao.html Time 100: Mao Zedong] By Jonathan D. Spence, 13 April 1998.</ref> Mao remains a controversial figure to this day. He is generally held in high regard in mainland China where he is often portrayed as a great revolutionary and strategist who eventually defeated Generalissimo [[Chiang Kai-shek]] in the [[Chinese Civil War]] and transformed the country into a [[major power]] through his policies. However, many of Mao's socio-political programs, such as the [[Great Leap Forward]] and the [[Cultural Revolution]], are blamed by critics from both within and outside China for causing severe damage to the [[Chinese culture|culture]], [[Chinese society|society]], [[Economy of the People's Republic of China|economy]], and [[Foreign relations of the People's Republic of China|foreign relations]] of China, as well as a probable death toll in the tens of millions.<ref name="Short, 761">{{cite book |last=Short |first=Philip |title=Mao: A Life |publisher=Owl Books |date=2001 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=2azuHQAACAAJ&dq=mao |pages=761}}</ref><ref>[[Jung Chang|Chang, Jung]] and [[Jon Halliday|Halliday, Jon]]. ''[[Mao: The Unknown Story]].'' [[Jonathan Cape]], London, 2005. ISBN 0224071262 p. 3</ref><ref>[[R. J. Rummel|Rummel, R. J.]] ''[http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/NOTE2.HTM China’s Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900]'' [[Transaction Publishers]], 1991. ISBN 088738417X p. 205 In light of recent evidence, Rummel has increased Mao's [[democide]] toll to [http://hawaiireporter.com/story.aspx?1c1d76bb-290c-447b-82dd-e295ff0d3d59 77 million].</ref> |

|||

'''Dakota Fanning''' (born February 23, 1994) is an [[United States|American]] teen [[actress]]. Fanning's breakthrough performance was in ''[[I Am Sam]]'' in 2001. As of 2007, her most well-known films have been ''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'', ''[[Charlotte's Web (2006 film)|Charlotte's Web]]'' and ''[[Man on Fire (2004 film)|Man on Fire]]''. She has won numerous awards, and is currently the youngest person ever to have been nominated for a [[Screen Actors Guild]] Award. |

|||

Although still officially venerated in China, his influence has been largely overshadowed by the political and [[Economic reform in the People's Republic of China|economic reforms]] of [[Deng Xiaoping]] and other leaders since his death.<ref>''Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping'' by Richard Baum</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/01/world/asia/01china.html?ex=1314763200&en=abf86c087b22be74&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss|title= Where’s Mao? Chinese Revise History Books|last= Kahn|first= Joseph|date= 2006-09-01|publisher= The New York Times}}</ref> Mao is also recognized as a [[poet]] and [[calligrapher]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Short |first=Philip |title=Mao: A Life |publisher=Owl Books |date=2001 |url=http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0805066381 |isbn=0805066381 |pages=630 |quote=Mao had an extraordinary mix of talents: he was visionary, statesman, political and military strategist of genius, philosopher and poet.}}</ref> |

|||

== Biography == |

|||

=== Early life === |

|||

Fanning was born in [[Conyers, Georgia]], the daughter of Joy ([[married and maiden names|née]] Arrington), who played [[tennis]] professionally, and Steve Fanning, who played [[minor league baseball]] for the [[St. Louis Cardinals]] and now works as an electronics salesman in [[Los Angeles, California|Los Angeles]] <ref>Fanning's Geneology at Ancestry.com</ref> Her maternal grandfather is [[football]] player [[Rick Arrington]] and her aunt is [[ESPN]] reporter [[Jill Arrington]].<ref name="milliondl">{{cite news|last=Stein|first=Joel|coauthors=|title=The Million-Dollar Baby|pages=|publisher=Time|date=[[2005-02-27]]|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1032353,00.html|accessdate=2007-12-10}}</ref> Fanning is the older sister of [[Elle Fanning]], also an actress. Fanning's mother had wanted to name her "Dakota" and her father wanted to name her "Hannah". Fanning is of half [[Germans|German]] descent and her last name is of [[Irish people|Irish]] origin.<ref name="timess">{{cite web | publisher=timessquare.com | title=Dakota Fanning Lives Out Her Dreams | url=http://timessquare.com/Movies/FILM_INTERVIEWS/Dakota_Fanning_Lives_Out_Her_Dreams/ | accessdate=July 21 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> Fanning and her family are members of the [[Southern Baptist Convention]].<ref name="lifeteen">{{cite web | publisher=lifeteen.com | title=Interview: Dakota Fanning | url=http://www.lifeteen.com/default.aspx?PageID=FEATUREDETAIL&__DocumentId=106317&__ArticleIndex=0 | accessdate=July 19 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> |

|||

== |

==Early life in China== |

||

Mao was guided by his good friend Chan Pak-Lam during his youth. His mother, Wen Chi-mei, was a very devout Buddhist. Due to his family's relative wealth, his father was able to send him to school and later to [[Changsha]] for more advanced schooling. |

|||

Fanning began acting at the age of five after appearing with [[Ray Charles]] in a [[television commercial]] for the state lottery<ref name="Georgia">{{cite web | publisher=Shoot magazine via findarticles.com | title=Winning Numbers | url=http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0DUO/is_13_41/ai_61693322 | accessdate=March 13 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> and being chosen for a [[Tide (detergent)|Tide]] [[television commercial|commercial]]. Her first significant acting job was a [[guest star|guest-starring]] role in the [[NBC]] [[prime time|prime-time]] [[drama]], ''[[ER (TV series)|ER]]'', which remains one of her favorite roles ("I played a car accident victim who has [[leukemia]]. I got to wear a neck brace and nose tubes for the two days I worked.")<ref name="jam">{{cite web | publisher=Jam! Movies | title=Fanning the flames | url=http://72.14.207.104/search?q=cache:ReI8vCDkr_gJ:www.canoe.ca/JamMoviesArtistsF/fanning_dakota.html+%22Dakota+Fanning%22+%22days+I+worked%22&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=6&lr=lang_en | accessdate=March 13 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> |

|||

During the [[1911 Revolution]], Mao enlisted as a soldier in a local regiment in [[Hunan]], which fought on the side of the revolutionaries. Once the [[Qing Dynasty]] had been effectively toppled, Mao left the army and returned to school.<ref>{{cite book |last=Feigon |first=Lee |title=Mao: A Reinterpretation |year=2002 |publisher=Ivan R. Dee |location=Chicago |isbn=1566635225 |pages=17 }}</ref> |

|||

Fanning subsequently had several guest roles on established television series, including ''[[CSI: Crime Scene Investigation]]'', ''[[Friends]]'', ''[[The Practice]]'', ''[[Spin City]]''. She also portrayed the title characters of ''[[Ally McBeal]]'' and ''[[The Ellen Show]]'' as young girls. In 2001, Fanning was chosen to star opposite [[Sean Penn]] in ''[[I Am Sam]]'', the story of a [[mental retardation|mentally retarded]] man who fights for the custody of his daughter (played by Fanning). |

|||

{| cellpadding=3px cellspacing=0px bgcolor=#f7f8ff style="float:right; border:1px solid; margin:5px" |

|||

This role made Fanning the youngest person (in 2002, at age eight) ever to be nominated for a [[Screen Actors Guild]] Award, for her supporting performance. When she won the Best Young Actor/Actress award from the [[Broadcast Film Critics Association]] for the film, she was too short to reach the microphone; presenter [[Orlando Bloom]] held her up for the duration of her acceptance speech. |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#ccf; border-top:1px solid; border-bottom:1px solid" colspan=3 | [[Chinese name|Names]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| || [[Chinese name|Given name]] || [[Chinese style name|Style name]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Traditional Chinese|Trad.]] || 毛澤東 || 潤之¹ |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Simplified Chinese|Simp.]] || {{lang|xh-cn|毛泽东}} || {{lang|zh-cn|润之}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Pinyin]] || Máo Zé-dōng || Rùnzhī |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Wade-Giles|WG]] || Mao Tse-tung || Jun-chih |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[help:IPA|IPA]] || {{IPA|/mau̯ː˧˥ tsɤ˧˥.tʊŋ˥/}} || {{IPA|/ʐuənː˥˩ tʂ̩˥/}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan=3 style="border-top:1px solid" | [[Surname]]: ''Mao'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan=3 style="border-top:1px solid" | [[Pseudonym]]: ''The Great [[Helmsman]]'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan=3 style="border-top:1px solid" | <small>¹Originally 詠芝({{lang|zh-cn|咏芝}}) then 润芝, in Xiangtan dialect<br /> have the same pronunciation ''yùnzhī''</small> |

|||

|} |

|||

After graduating from the [[First Provincial Normal School of Hunan]] in 1915, Mao traveled with Professor [[Yang Changji]], his high school teacher and future father-in-law, to [[Beijing]] during the [[May Fourth Movement]] in 1923. |

|||

Professor Yang held a faculty position at [[Peking University]]. Because of Yang's recommendation, Mao worked as an assistant librarian at the University with [[Li Dazhao]] as curator. Mao registered as a part-time student at Beijing University and attended many lectures and seminars by famous intellectuals, such as [[Chen Duxiu]], [[Hu Shi]], and [[Qian Xuantong]]. During his stay in Beijing, he engaged himself as much as possible in reading, which introduced him to [[Communist]] theories. He married [[Yang Kaihui]], Professor Yang's daughter and a fellow student, despite an existing marriage arranged by his father at home. Mao never acknowledged this marriage. In October 1930, the Kuomintang (KMT) captured [[Yang Kaihui]] as well as her son, Anying. The KMT imprisoned them both, and Anying was later sent to his relatives after the KMT killed his mother. At this time , Mao was living with [[He Zizhen]], a co-worker and 17 year old girl from [[Yongxing]], [[Jiangxi]].<ref>Hollingworth, Clare, Mao and the men against him (Jonathan Cape, London: 1985), p. 45.</ref> Mao turned down an opportunity to study in [[France]] because he firmly believed that China's problems could be studied and resolved only within China. Unlike his contemporaries, Mao concentrated on studying the peasant majority of China's population. |

|||

=== 2002–2003 === |

|||

In 2002, director [[Steven Spielberg]] cast Fanning in the lead child role of Allison "Allie" Clarke/Keys in the [[science fiction]] [[miniseries]] ''[[Taken]]''. By this time, she had received positive notices by several film critics, including Tom Shales of ''[[The Washington Post]]'', who wrote that Fanning "has the perfect sort of otherworldly look about her, an enchanting young actress called upon ... to carry a great weight."<ref name="post">{{cite web | publisher=The Washington Post via virtuallystrange.net | title=Sci Fi's 'Taken' Grabs You and Doesn't Let Go | url=http://www.virtuallystrange.net/ufo/updates/2002/dec/m03-004.shtml | accessdate=March 13 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> |

|||

On 28 July 1920, Mao, age 24, attended the first session of the [[National Congress of the Communist Party of China]] in [[Shanghai]]. Two years later, he was elected as one of the five commissars of the Central Committee of the Party during the third Congress session. Later that year, Mao returned to Hunan at the instruction of the CPC Central Committee and the Kuomintang Central Committee to organize the Hunan branch of the Kuomintang.<ref name="chronology">[http://news.163.com/05/0908/11/1T4IGSAR00011246_2.html 毛泽东生平大事(1893-1976)] (Major event chronology of Mao Zedong (1891-1977), People's Daily.</ref> In 1923, he was a delegate to the first National Conference of the Kuomintang, where he was elected an Alternate Executive of the Central Committee. In 1924, he became an Executive of the Shanghai branch of the Kuomintang and Secretary of the Organization Department. |

|||

In the same year, Fanning appeared in three films: As a kidnap victim who proves to be more than her abductors bargained for in ''[[Trapped (2002 film)|Trapped]]''; as the young version of [[Reese Witherspoon]]'s character in ''[[Sweet Home Alabama (film)|Sweet Home Alabama]]'', and as Katie in the movie ''[[Hansel and Gretel (2002 film)|Hansel and Gretel]]''. |

|||

For a while, Mao remained in Shanghai, an important city that the CPC emphasized for the [[Revolution]]. However, the Party encountered major difficulties organizing labor union movements and building a relationship with its nationalist ally, the [[Kuomintang]] (KMT). The Party had become poor, and Mao became disillusioned with the revolution and moved back to Shaoshan. During his stay at home, Mao's interest in the revolution was rekindled after hearing of the 1925 uprisings in Shanghai and Guangzhou. His political ambitions returned, and he then went to Guangdong, the base of the Kuomintang, to take part in the preparations for the second session of the National Congress of Kuomintang. In October 1926, Mao became acting Propaganda Director of the Kuomintang.<ref name="chronology"/> |

|||

Fanning was featured even more prominently in two films released in 2003: Playing the uptight child to [[Brittany Murphy]]'s immature nanny in ''[[Uptown Girls]]'', and as Sally in ''[[The Cat in the Hat (film)|The Cat in the Hat]]''. |

|||

In early 1926, Mao returned to Hunan where, in an urgent meeting held by the Communist Party, he made a report based on his investigations of the peasant uprisings in the wake of the [[Northern Expedition (1925–1929)|Northern Expedition]]. This is considered the initial and decisive step towards the successful application of Mao's revolutionary theories.<ref name="peasant">{{cite web|url=http://www.etext.org/Politics/MIM/classics/mao/sw1/mswv1_2.html|title='Report on an investigation of the peasant movement in Hunan' Mao Zedong 1924}}</ref> |

|||

Fanning did [[voice-over]] work for four [[animation|animated]] projects during this period: As Satsuki in [[Walt Disney Pictures|Disney]]'s [[English language]] release of ''[[My Neighbor Totoro]]'', as [[Kim Possible (character)|Kim Possible]] in [[nursery school|preschool]] in the [[Disney Channel]] series ''[[Kim Possible]]'', as a little girl in the [[Fox Broadcasting Company|Fox]] series ''[[Family Guy]]'', and as young [[Wonder Woman]] in an episode of [[Cartoon Network]]'s ''[[Justice League]]''. |

|||

==Political ideas== |

|||

=== 2004–2005 === |

|||

{{main|Maoism}} |

|||

[[Image:Dakota Fanning cropped.jpg|left|thumb|Dakota Fanning at the London premiere of ''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'' in June 2005.]] |

|||

In 2004, Fanning appeared in ''[[Man on Fire (2004 film)|Man on Fire]]'' as Pita, a nine-year-old who wins over the heart of a retired [[assassination|assassin]] ([[Denzel Washington]]) hired to protect her from kidnappers. [[Roger Ebert]] wrote that Fanning "is a pro at only 10 years old, and creates a heart-winning character."<ref name="ebert">{{cite web | publisher=rogerebert.com | title=Man on Fire (review) | url=http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20040423/REVIEWS/404230302/1023 | accessdate=March 13 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> |

|||

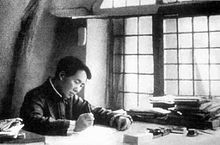

[[Image:Mao-young.jpg|right|thumb|Mao as very a young man.]] |

|||

''[[Hide and Seek (2005 film)|Hide and Seek]]'', was her first release in 2005, opposite [[Robert De Niro]]. The film was generally panned, and critic Chuck Wilson called it "a fascinating meeting of equals — if the child star [Fanning] challenged the master [De Niro] to a game of stare-down, the legend might very well blink first."<ref name="laweekly">{{cite web | publisher=laweekly.com | title=Hide and Seek review | url=http://www.laweekly.com/film/film_results.php?showid=3257 | accessdate=March 13 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> Fanning voiced Lilo (succeeding [[Daveigh Chase]]) in the [[direct-to-video]] film ''[[Lilo & Stitch 2: Stitch Has a Glitch]]''. She also had a small part in the [[Rodrigo Garcia]] film ''[[Nine Lives (2005 film)|Nine Lives]]'' (released in October 2005), in which she shared an unbroken nine-minute scene with actress [[Glenn Close]], who had her own praise for Fanning: "She's definitely an old soul. She's one of those gifted people that come along every now and then."<ref name="close">{{cite web | publisher=monstersandcritics.com | title=Glenn Close raves about Dakota Fanning | url=http://movies.monstersandcritics.com/news/article_1049828.php | accessdate=March 13 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> |

|||

Mao had a great interest in the political system, encouraged by his father. His two most famous essays, both from 1934, 'On Contradiction' and 'On Practice', are concerned with the practical strategies of a revolutionary movement and stress the importance of practical, grassroots knowledge, obtained through experience. Both essays reflect the guerrilla roots of Maoism in the need to build up support in the countryside against a Japanese occupying force and emphasise the need to win over 'hearts and minds' through 'education'. The essays, reproduced later as part of the 'Red Book', warn against the behaviour of the blindfolded man trying to catch sparrows, and the 'Imperial envoy' descending from his carriage to 'spout opinions'. |

|||

[[Image:WotW pub.jpg|thumb|Fanning in ''War of the Worlds''; Director Steven Spielberg praised her ability to show "how she would really react in a real situation".]] |

|||

Fanning completed filming on ''[[Dreamer: Inspired by a True Story]]'' (opposite [[Kurt Russell]]) in late October 2004. Russell declared he was astonished by his co-star's performance in the film. Russell, 54, who plays her father in the movie, declared she is the best actress he worked with in his entire career and that he was astonished by her acting ability and well-rounded attitude. Russell says, "I guarantee you, (Dakota) is the best actress I will work with in my entire career." <ref>{{cite web | publisher=softpedia.com | title=Kurt Russell Says Dakota Fanning Is The Best Actress He Ever Played With | url=http://news.softpedia.com/news/Kurt-Russell-Says-Dakota-Fanning-Is-The-Best-Actress-He-Ever-Played-With-8779.shtml |

|||

| accessdate=April 12 | accessyear=2007}}</ref> |

|||

[[Kris Kristofferson]], who plays her character's grandfather in the movie, said that she's like [[Bette Davis]] [[Reincarnation|reincarnated]].<ref name="bette">{{cite web | publisher=reel.com | title= Dreamer: Inspired By a True Story (2005) DVD Review | url=http://www.reel.com/movie.asp?MID=141246&PID=10121575&Tab=reviews&CID=18 | accessdate=January 28 | accessyear=2007}}</ref> |

|||

In addition to his limited formal education, Mao spent six months studying independently. Mao was first introduced to communism while working at [[Peking University]], and in 1921 he co-founded the Communist Party of China (or CPC) He first encountered Marxism while he worked as a library assistant at Peking University. |

|||

While promoting her role in ''Dreamer'', Fanning became a registered member of [[Girl Scouts of the USA]] at a special ceremony, which was followed by a screening of the film for members of the Girl Scouts of the San Fernando Valley Council. She is not a member of a troop, but rather registered as a "[[Juliette (Girl Scouts)|Juliette]]" ([[GSUSA]]'s title for independently registered girls). |

|||

<ref>{{cite web | publisher=girlscouts.org| title= Dakota Fanning, Movie Star and Girl Scout | url=http://www.girlscouts.org/news/news_releases/2005/dakota_fanning.asp | accessdate=April 28 | accessyear=2007}}</ref> |

|||

Other important influences on Mao were the [[Russian Revolution of 1917|Russian revolution]] and, according to some scholars, the Chinese literary works: ''[[Outlaws of the Marsh]]'' and ''[[Romance of the Three Kingdoms]]''. Mao sought to subvert the alliance of imperialism and feudalism in China. He thought the [[Kuomintang|Nationalists]] to be both economically and politically vulnerable and thus that the revolution could not be steered by Nationalists. |

|||

She then went directly to the set of ''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'', starring alongside [[Tom Cruise]]. Released in reverse order (''War'' in June 2005 and ''Dreamer'' in the following October), both films were critical successes. ''War'' director [[Steven Spielberg]] praised "how quickly she understands the situation in a sequence, how quickly she sizes it up, measures it up and how she would really react in a real situation."<ref name="comingsoonet">{{cite web | publisher=comingsoon.net | title=War of the Worlds: Spielberg & Cruise - Part I | url=http://www.comingsoon.net/news.php?id=10136 | accessdate=March 13 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> |

|||

Throughout the 1930s, Mao led several labour struggles based upon his studies of the propagation and organization of the contemporary labour movements.<ref name="vaughan">{{cite book | title=Mao Zedong As Poet and Revolutionary Leader: Social and Historical Perspectives| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=EWtBMQgUGmEC| last=Chunhou| first=Zhang. C| id=ISBN 0739104063}}</ref> However, these struggles were successfully subdued by the government, and Mao fled from [[Changsha]] after he was labeled a ''radical activist''. He pondered these failures and finally realized that [[industrial]] workers were unable to lead the revolution because they made up only a small portion of China's population, and unarmed labour struggles could not resolve the problems of imperial and feudal suppression. |

|||

After filming was completed on ''War of the Worlds'', Fanning moved straight to another film, without a break: ''[[Charlotte's Web (2006 film)|Charlotte's Web]]'', which she finished filming in May 2005, in [[Australia]]. Released on December 15, 2006, ''Web'' met generally warm critical acclaim. Producer Jordan Kerner said, "...when she was so caught up in ''War of the Worlds'', we had to end up going on a search for other young actresses. They would have been nothing compared to her."<ref name="Moviehole.net">{{cite web | publisher=moviehole.net | title=Exclusive Interview : Jordan Kerner | url=http://www.moviehole.net/interviews/20061204_exclusive_interview_jordan_ker.html | accessdate=December 15 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> Fanning also provided voice work for ''[[Coraline (film)|Coraline]]'', scheduled for release sometime in 2008.<ref name="coraline">{{cite web | publisher=about.com | title=Dakota Fanning Signs on to "Coraline" | url=http://movies.about.com/od/moviesinproduction/a/coraline102505.htm | accessdate=March 13 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> |

|||

Mao began to depend on Chinese peasants who later became staunch supporters of his theory of violent revolution. This dependence on the rural rather than the urban proletariat to instigate violent revolution distinguished Mao from his predecessors and contemporaries. Mao himself was from a peasant family, and thus he cultivated his reputation among the farmers and peasants and introduced them to Marxism.<ref name="peasant"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.etext.org/Politics/MIM/classics/mao/sw1/mswv1_1.html|title='Analysis of the classes in Chinese society' Mao Zedong 1927.}}</ref> |

|||

===2006–2007=== |

|||

Over the summer of 2006, Fanning worked on the film ''[[Hounddog (film)|Hounddog]]'', described in press reports as a "dark story of [[abuse]], violence and [[Elvis Presley]] adulation in the rural South." <ref name="hounddog">{{cite web | publisher=nydailynews.com | title=All shook up over Dakota's Hounddog | url=http://www.nydailynews.com/front/story/436645p-367837c.html | accessdate=July 20 | accessyear=2006}}</ref> Fanning's parents have been criticized for allowing her to film a scene in which her character is [[rape]]d. "It's not really happening," she told [[Reuters]]. "It's a movie, and it's called acting."<ref name="attack">{{cite web | publisher=cnn.com | title=Dakota Fanning: 'It's called acting' | url=http://www.cnn.com/2007/SHOWBIZ/Movies/01/24/sundance.fanning.ap/ | accessdate=January 29 | accessyear=2007}}</ref> Director Deborah Kampmeier addressed the controversy in the January 2007 edition of ''[[Premiere]]'': "The assumption that [Dakota] was violated in order to give this performance denies her talent."<ref name="premiere">{{cite news | title=No More Kid Stuff | publisher=Premiere | date=January 2007}}</ref> |

|||

==War and Revolution== |

|||

In 2006, at the age of 12, she was invited to join the [[Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences]], becoming the youngest member in the Academy's history.<ref>{{cite news | title=Brokeback stars to join Academy | url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/5153130.stm | publisher=BBC | date=April 2007}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Mao1928.jpg|left|thumb|Mao in 1927]] |

|||

In 1928, Mao conducted the famous [[Autumn Harvest Uprising]] in [[Changsha]], [[Hunan]], as commander-in-chief. Mao led an army, called the "Revolutionary Army of Workers and Peasants", which was defeated and scattered after fierce battles. Afterwards, the exhausted troops were forced to leave Hunan for [[Sanwan]], Jiangxi, where Mao re-organized the scattered soldiers, rearranging the military division into smaller regiments. Mao also ordered that each company must have a party branch office with a commissar as its leader who would give political instructions based upon superior mandates. This military rearrangement in Sanwan, Jiangxi initiated the CPC's absolute control over its military force and has been considered to have the most fundamental and profound impact upon the Chinese revolution. Later, they moved to the [[Jinggang Mountains]], Jiangxi. |

|||

In [[March 2007|March]] and April 2007, she filmed ''[[Winged Creatures]]'', alongside [[Kate Beckinsale]], [[Guy Pearce]], [[Josh Hutcherson]], and [[Academy Award]] winners [[Forest Whitaker]] and [[Jennifer Hudson]]. She plays Anne Hagen, a girl who witnesses her father's [[murder]] and who turns to religion in the aftermath. |

|||

In the Jinggang Mountains, Mao persuaded two local insurgent leaders to pledge their allegiance to him. There, Mao joined his army with that of [[Zhu De]], creating the [[Workers' and Peasants' Red Army of China]], [[Red Army]] in short. (the [[Fourth Front of Workers' and Peasants' Red Army of China]]). |

|||

In July 2007, Fanning filmed for three days a short film titled ''Cutlass'', one of [[Glamour magazine|''Glamour'']]'s "Reel Moments" based on readers' personal essays. ''Cutlass'' was directed by [[Kate Hudson]]. |

|||

From 1933 to 1937, Mao helped establish the [[Soviet Republic of China]] and was elected Chairman of this small republic in the mountainous areas in Jiangxi. Here, Mao was married to [[He Zizhen]]. His previous wife, [[Yang Kaihui]], had been arrested and executed in 1932, just four years after their departure. |

|||

From September to December 2007, Fanning filmed ''[[Push (2009 film)|Push]]'' which centers on a group of young American expatriates with [[telekinesis|telekinetic]] and [[clairvoyant]] abilities who hide from a U.S. government agency in [[Hong Kong]] and band together to try to escape the control of the division.<ref name="Vanity Fair">{{cite news | title=Fanning set to 'Push' for McGuigan | url= http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117970403.html?categoryid=13&cs=1 | publisher=[[Vanity Fair (magazine)|Vanity Fair]] | date=August 2007}}</ref> Dakota plays Cassie Holmes, a thirteen-year-old futureteller. |

|||

[[Image:Mao1931.jpg|right|thumb|Mao in 1935]] |

|||

===2008–present=== |

|||

In January 2008, Fanning began filming the [[The Secret Life of Bees (film)|movie adaptation]] of ''[[The Secret Life of Bees]]'', a novel by [[Sue Monk Kidd]].<ref name="Variety">{{cite news | title=Cast set for 'Secret Life of Bees' |

|||

| url= http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117977996.html?categoryid=13&cs=1 | date=December 2007}}</ref> Set in [[South Carolina]] in 1964, the story centers on Lily Owens (Fanning), who escapes her lonely life and troubled relationship with her father by running away with her caregiver and only friend (played by [[Jennifer Hudson]]) to a South Carolina town where they are taken in by an eccentric trio of beekeeping sisters (played by [[Queen Latifah]], [[Sophie Okonedo]] and [[Alicia Keys]]). Production wrapped in February.<ref name="bees-wrapped"> {{cite news | first=Bruce | last=Smith | title='Bees' author gives film A-OK |

|||

| url= http://www.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/ae/articles/0323secretlifeofbees.html | date=2008-03-23 | accessdate=2008-04-13 }}</ref> Dakota is now a sophomore in high school and is on the varsity cheerleading squad. |

|||

In Jiangxi, Mao's authoritative domination, especially that of the military force, was challenged by the Jiangxi branch of the CPC and military officers. Mao's opponents, among whom the most prominent was [[Li Wenlin]], the founder of the CPC's branch and Red Army in Jiangxi, were against Mao's land policies and proposals to reform the local party branch and army leadership. Mao reacted first by accusing the opponents of [[opportunism]] and [[kulak]]ism and then set off a series of systematic suppressions of them.<ref>{{cite book|last=Lynch|first=Michael J|title=Mao|year=2004|isbn=0415215773|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=fzVSkyaBIGEC&}}</ref> It is reported that horrible forms of torture and killing took place. Jung Chang and Jon Halliday claim that victims were subjected to a red-hot gun-rod being rammed into the anus, and that there were many cases of cutting open the stomach and scooping out the heart.<ref>Jung Chang and Jon Halliday. ''Mao: The Unknown Story.'' pp 99 & 100</ref> The estimated number of the victims amounted to several thousands and could be as high as 186,000.<ref>Jean-Luc Domenach. ''Chine: L'archipel oublie.'' (''China: The Forgotten Archipelago.'') Fayard, 1992. ISBN 2213025819 pg 47</ref> Critics accuse Mao's authority in Jiangxi was secured and reassured through the [[revolutionary terrorism]], or [[Red Terror#Historical significance of the Red Terror|red terrorism]]. |

|||

== Filmography == |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

!Year |

|||

!Film |

|||

!Role |

|||

!Notes |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="3"|[[2001 in film|2001]] |

|||

|''[[Father Xmas]]'' |

|||

|Clairee |

|||

|''20-[[minute]] [[short subject]]'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[I Am Sam]]'' |

|||

|Lucy Diamond Dawson |

|||

|''Shared role with sister [[Elle Fanning]]'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Tomcats]]'' |

|||

|Little Girl in Park |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="4"|2002 |

|||

|''[[Taken]]'' (TV) |

|||

|Allison "Allie" Clarke/Keys |

|||

|''[[Miniseries]]'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Trapped (2002 film)|Trapped]]'' |

|||

|Abigail Jennings |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Sweet Home Alabama (film)|Sweet Home Alabama]]'' |

|||

|Melanie (as a child) |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Hansel and Gretel]]'' |

|||

|Katie |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="3"|[[2003 in film|2003]] |

|||

|''[[Uptown Girls]]'' |

|||

|Lorraine "Ray" Schleine |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[The Cat in the Hat (film)|The Cat in the Hat]]'' |

|||

|Sally |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Kim Possible: A Sitch in Time]]'' |

|||

|Preschool Kim (voice) |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="3"|[[2004 in film|2004]] |

|||

|''[[Man on Fire (2004 film)|Man on Fire]]'' |

|||

|Lupita Martin Ramos |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[My Neighbor Totoro]]'' |

|||

|Satsuki Kusakabe (voice) |

|||

|''[[English (language)|English]]-language re-release; directed by [[Hayao Miyazaki]]'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[In the Realms of the Unreal]]'' |

|||

|Narrator (voice) |

|||

|| |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="5"|[[2005 in film|2005]] |

|||

|''[[Hide and Seek (2005 film)|Hide and Seek]]'' |

|||

|Emily Callaway |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'' |

|||

|Rachel Ferrier |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Lilo & Stitch 2]]'' |

|||

|Lilo (voice) |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Dreamer (2005 film)|Dreamer]]'' |

|||

|Cale Crane |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Nine Lives (2005 film)|Nine Lives]]'' |

|||

|Maria |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="1"|[[2006 in film|2006]] |

|||

|''[[Charlotte's Web (2006 film)|Charlotte's Web]]'' |

|||

|Fern Arable |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="2"|[[2007 in film|2007]] |

|||

|''[[Hounddog (film)|Hounddog]]'' |

|||

|Lewellen |

|||

|''Wide release date September, 2008'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|''Cutlass'' |

|||

|Lacy |

|||

|''Short film, available online'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="3"|[[2008 in film|2008]] |

|||

|''[[Winged Creatures]]'' |

|||

|Anne Hagen |

|||

|''Awaiting release'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[The Secret Life of Bees (film)|The Secret Life of Bees]]'' |

|||

|Lily Owens |

|||

|''Awaiting release, release October 17, 2008'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Coraline (film)|Coraline]]'' |

|||

|Coraline (voice) |

|||

|''Post-production, limited release December 2008, wide release February 6, 2009'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="2"|[[2009 in film|2009]] |

|||

|''[[Push (2009 film)|Push]]'' |

|||

|Cassie Holmes |

|||

|''Post-production, release aimed for February 2009'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|''Hurricane Mary'' |

|||

|Narrator |

|||

|''Pre-production, Sister [[Elle Fanning]] plays Anastasia'' |

|||

|} |

|||

Mao, with the help of [[Zhu De]], built a modest but effective army, undertook experiments in rural reform and government, and provided refuge for Communists fleeing the rightist purges in the cities. Mao's methods are normally referred to as Guerrilla warfare; but he himself made a distinction between guerrilla warfare (''youji zhan'') and [[Mobile Warfare]] (''yundong zhan''). |

|||

== Notable TV guest appearances == |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

!Year |

|||

!TV show |

|||

!Role |

|||

!Episode |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="6"|2000 |

|||

|''[[ER (TV Series)|ER]]'' |

|||

|Delia Chadsey |

|||

|"The Fastest Year" |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Ally McBeal]]'' |

|||

|Ally (5 years) |

|||

|"Ally McBeal: The Musical, Almost" |

|||

|- |

|||

||''[[Strong Medicine]]'' |

|||

|Edie's Girl |

|||

|"Misconceptions" |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[CSI: Crime Scene Investigation]]'' |

|||

|Brenda Collins |

|||

|"Blood Drops" |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[The Practice]]'' |

|||

|Alessa Engel |

|||

|"The Deal" |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Spin City]]'' |

|||

|Cindy |

|||

|"Toy Story" |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="4"|2001 |

|||

|''[[Malcolm In The Middle]]'' |

|||

|Emily |

|||

|"New Neighbors" |

|||

|- |

|||

|''The Fighting Fitzgeralds'' |

|||

|Marie |

|||

|"Pilot" |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Family Guy]]'' |

|||

|Little girl |

|||

|"To Love and Die in Dixie" |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[The Ellen Show]]'' |

|||

|Young Ellen |

|||

|"Missing the Bus" |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan="2"|2004 |

|||

|''[[Justice League Unlimited]]'' |

|||

|Young Wonder Woman (voice) |

|||

|"Kid Stuff" |

|||

|- |

|||

|''[[Friends (TV Show)|Friends]]'' |

|||

|Mackenzie |

|||

|"The One with Princess Consuela" |

|||

|} |

|||

Mao's [[Guerrilla Warfare]] and [[Mobile Warfare]] was based upon the fact of the poor armament and military training of the red army which consisted mainly of impoverished peasants, who, however, were all encouraged by revolutionary passions and aspiring after a communist [[utopia]]. |

|||

== Awards == |

|||

'''[[Kids Choice Awards]]'''<br> |

|||

*2007 Favorite Movie Actress |

|||

Around 1930, there had been more than ten regions, usually entitled "[[soviet areas]]," under control of the CPC.<ref name="cambridge">{{cite book | title=The Cambridge History of China (vol. 13, pt. 2)| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Fxs3ROaIhPMC| last=Fairbank| first=John K| coauthors=Albert Feuerwerker| publisher=Cambridge University Press| id=ISBN 0521243386}}</ref> The prosperity of "soviet areas" startled and worried [[Chiang Kai-shek]], chairman of the Kuomintang government, who waged five waves of besieging campaigns against the "central soviet area." More than one million Kuomintang soldiers were involved in these five campaigns, four of which were defeated by the red army led by Mao. By June 1932 (the height of its power), the Red Army had no less than 45,000 soldiers, with a further 200,000 local militia acting as a subsidiary force.<ref name="mobmass">{{cite book | title=Mobilizing the Masses: Building Revolution in Henan| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=1BN9dAqprX8C&| last=Ying-kwong Wou| first=Odoric| date=1994| publisher=Stanford University Press| id=ISBN 0804721424}}</ref> |

|||

'''[[Saturn Award]]'''<br> |

|||

*2006 Best Performance by a Younger Actor, ''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'' |

|||

Under increasing pressures from the KMT encirclement campaigns, there was a struggle for power within the Communist leadership. Mao was removed from his important positions and replaced by individuals (including [[Zhou Enlai]]) who appeared loyal to the orthodox line advocated by Moscow and represented within the CPC by a group known as the [[28 Bolsheviks]]. |

|||

'''[[BFCA Awards|BFCA Award]]'''<br> |

|||

[[Image:Mao.gif|right|thumb|Mao in 1935]] |

|||

*2006 Best Young Actress, ''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'' |

|||

*2002 Best Young Actor/Actress, ''[[I Am Sam]]'' |

|||

[[Chiang Kai-shek]], who had earlier assumed nominal control of China due in part to the Northern Expedition, was determined to eliminate the Communists. By October 1934, he had them surrounded, prompting them to engage in the "[[Long March]]," a retreat from Jiangxi in the southeast to [[Shaanxi]] in the northwest of China. It was during this 9,600 kilometer (5,965 mile), year-long journey that Mao emerged as the top Communist leader, aided by the [[Zunyi Conference]] and the defection of [[Zhou Enlai]] to Mao's side. At this Conference, Mao entered the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Communist Party of China. |

|||

'''[[Sierra Awards|Sierra Award]]'''<br> |

|||

*2005 Youth in Film, ''[[War of the Worlds (2005 film)|War of the Worlds]]'' |

|||

*2002 Youth in Film, ''[[I Am Sam]]'' |

|||

According to the standard Chinese Communist Party line, from his base in [[Yan'an]], Mao led the Communist resistance against the Japanese in the [[Second Sino-Japanese War]] (1937-1945).{{Fact|date=August 2007}} However, Mao further consolidated power over the Communist Party in 1942 by launching the [[Zheng Feng]], or "Rectification" campaign against rival CPC members such as [[Wang Ming]], [[Wang Shiwei]], and [[Ding Ling]]. Also while in Yan'an, Mao divorced He Zizhen and married the actress Lan Ping, who would become known as [[Jiang Qing]]. |

|||

'''[[Bronze Leopards|Bronze Leopard]]'''<br> |

|||

*2005 Best Actress (shared with other cast members), ''[[Nine Lives (2005 film)|Nine Lives]]'' |

|||

[[Image:Mao1938a.jpg|left|thumb|Mao in 1938, writing ''On Protracted War'' <ref>http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-2/mswv2_09.htm</ref>]] |

|||

'''[[MTV Movie Award]]'''<br> |

|||

*2005 Best Frightened Performance, ''[[Hide and Seek (2005 film)|Hide and Seek]]'' |

|||

During the Sino-Japanese War, Mao Zedong's strategies were opposed by both Chiang Kai-shek and the United States. The US regarded Chiang as an important ally, able to help shorten the war by engaging the Japanese occupiers in China. Chiang, in contrast, sought to build the ROC army for the certain conflict with Mao's communist forces after the end of [[World War II]]. This fact was not understood well in the US, and precious [[lend-lease]] armaments continued to be allocated to the Kuomintang. In turn, Mao spent part of the war (as to whether it was most or only a little is disputed) fighting the Kuomintang for control of certain parts of China. Both the Communists and Nationalists have been criticised for fighting amongst themselves rather than allying against the Japanese Imperial Army. However the Nationalists were better equipped and did most of the fighting against the Japanese army in China.<ref name=Lam/> |

|||

'''[[Satellite Awards|Satellite Award]]''':Special Achievement Award<br> |

|||

*2002 Outstanding New Talent, ''[[I Am Sam]]'' |

|||

In 1944, the Americans sent a special diplomatic envoy, called the [[Dixie Mission]], to the Communist Party of China. According to Edwin Moise, in ''Modern China: A History 2nd Edition'': |

|||

'''[[Young Artist Award]]'''<br> |

|||

*2006 Best Performance in a Feature Film (Comedy or Drama) - Leading Young Actress, ''[[Dreamer: Inspired by a True Story]]'' |

|||

: ''Most of the Americans were favorably impressed. The CPC seemed less corrupt, more unified, and more vigorous in its resistance to [[Japan]] than the [[Guomindang]]. United States fliers shot down over North China...confirmed to their superiors that the CPC was both strong and popular over a broad area. In the end, the contacts with the USA developed with the CPC led to very little.'' |

|||

*2002 Best Performance in a Feature Film - Young Actress Age Ten or Under, ''[[I Am Sam]]'' |

|||

Then again, modern commentators have disputed such claims. Amongst others, Willy Lam stated that during the war with Japan: |

|||

: ''The great majority of casualties sustained by Chinese soldiers were borne by KMT, not Communist divisions. Mao and other guerrilla leaders decided at the time to conserve their strength for the "larger struggle" of taking over all of China once the Japanese Imperial Army was decimated by the U.S.-led Allied Forces.''<ref name=Lam>"[http://hnn.us/roundup/entries/13999.html Willy Lam: China's Own Historical Revisionism]", [[History News Network]], 11 August 2005. Retrieved 15 May 2006.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Mao1946.jpg|right|thumb|Mao in 1946 in [[Yan'an]]]] |

|||

After the end of World War II, the U.S. continued to support Chiang Kai-shek, now openly against the Communist [[People's Liberation Army|Red Army]] (led by Mao Zedong) in the [[Chinese Civil War|civil war]] for control of China. The U.S. support was part of its view to contain and defeat world communism. Likewise, the Soviet Union gave quasi-covert support to Mao (acting as a concerned neighbor more than a military ally, to avoid open conflict with the U.S.) and gave large supplies of arms to the Communist Party of China, although newer Chinese records indicate the Soviet "supplies" were not as large as previously believed, and consistently fell short of the promised amount of aid. |

|||

On 21 January 1949, Kuomintang forces suffered massive losses against Mao's Red Army. In the early morning of 10 December 1949, Red Army troops laid siege to [[Chengdu]], the last KMT-occupied city in mainland China, and Chiang Kai-shek evacuated from the mainland to [[Taiwan]] (Formosa) that same day. |

|||

==Leadership of China== |

|||

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[Image:Mzd25.jpg|right|thumb|[[Propaganda in the People's Republic of China|Chinese poster]] depicting Mao as "the Helmsman", his revolutionary epitaph, 1969]] --> |

|||

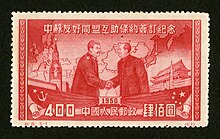

[[Image:Chinese stamp in 1950.jpg|[[Joseph Stalin]] and Mao depicted on a Chinese [[postage stamp]]|left|thumb]] |

|||

The [[People's Republic of China]] was established on 1 October 1949. It was the culmination of over two decades of civil and international war. From 1954 to 1959, Mao was the [[President of the People's Republic of China|Chairman of the PRC]]. During this period, Mao was called Chairman Mao ({{lang|zh-cn|毛主席}}) or the Great Leader Chairman Mao ({{lang|zh-cn|伟大领袖毛主席}}). The Communist Party assumed control of all media in the country and used it to promote the image of Mao and the Party. The Nationalists under General [[Chiang Kai-Shek]] were vilified as were countries such as the United States of America and Japan. The Chinese people were exhorted to devote themselves to build and strengthen their country. In his speech declaring the foundation of the PRC, Mao announced: "The Chinese people have stood up!" |

|||

Mao took up residence in [[Zhongnanhai]], a compound next to the [[Forbidden City]] in Beijing, and there he ordered the construction of an indoor swimming pool and other buildings. Mao often did his work either in bed or by the side of the pool, preferring not to wear formal clothes unless absolutely necessary, according to Dr. [[Li Zhisui]], his personal physician. (Li's book, ''[[The Private Life of Chairman Mao]]'', is regarded as controversial, especially by those sympathetic to Mao.) |

|||

Mao’s first political campaigns after founding the People’s Republic were [[land reform]] and the suppression of [[counter-revolutionaries]], which centered on mass executions, often before organized crowds. These campaigns of mass [[Political repression|repression]] targeted former KMT officials, businessmen, former employees of Western companies, intellectuals whose loyalty was suspect, and significant numbers of rural [[Gentry#China|gentry]].<ref> Steven W. Mosher. ''China Misperceived: American Illusions and Chinese Reality.'' [[Basic Books]], 1992. ISBN 0465098134 pp 72, 73</ref> The [[United States Department of State|U.S. State department]] in 1976 estimated that there may have been a million killed in the land reform, 800,000 killed in the counterrevolutionary campaign.<ref>Stephen Rosskamm Shalom. ''Deaths in China Due to Communism.'' Center for Asian Studies Arizona State University, 1984. ISBN 0939252112 pg 24</ref> Mao himself claimed a total of 700,000 killed during the years 1949–53.<ref>Jung Chang and Jon Halliday. ''Mao: The Unknown Story.'' pg 337: ''"Mao claimed that the total number executed was 700,000, but this did not include those beaten or tortured to death in the post-1949 land reform, which would at the very least be as many again. Then there were suicides, which, based on several local inquiries, were very probably about equal to the number of those killed."'' Also cited in ''Mao Zedong'', by [[Jonathan Spence]], as cited [http://www.nytimes.com/books/00/02/06/reviews/000206.06burnst.html].</ref> However, because there was a policy to select "at least one landlord, and usually several, in virtually every village for public execution",<ref>{{cite book |last=Twitchett |first=Denis |coauthors=John K. Fairbank |title=The Cambridge history of China |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=052124336X |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ioppEjkCkeEC&pg=PA87&dq=at+least+one+landlord,+and+usually+several,+in+virtually+every+village+for+public+execution&ei=wP14R6muKIi0iQHR4ezAAQ&ie=ISO-8859-1&sig=9REVjFOEIx_4TIMFixd7fhgC9FY |accessdate=2008-08-23}}</ref> 1 million deaths seems to be an absolute minimum, and many authors agree on a figure of between 2 million and 5 million dead.<ref> [[Stephane Courtois]], et al. ''[[The Black Book of Communism]]: Crimes, Terror, Repression.'' [[Harvard University Press]], 1999. ISBN 0674076087 pg. 479</ref><ref>[http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/CHINA.TABIIA.1.GIF Estimates, sources and calculations] from [[R. J. Rummel|R.J. Rummel’s]] ''[http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/NOTE2.HTM China’s Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900]'' (See lines 1 through 90.)</ref> In addition, at least 1.5 million people were sent to [[laogai|"reform through labour"]] camps.<ref>{{cite book |last=Short |first=Philip |title=Mao: A Life |publisher=Owl Books |date=2001 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=HQwoTtJ43_AC&pg=PA436&dq=%27%27At+least+a+million-and-a-half+more+disappeared+into+the+newly+established+%27reform+through+labour%27+camps,+purpose-built+to+accommodate+them&ei=L_54R6eOFYq-igG72-2XCA&ie=ISO-8859-1&sig=lJa-WxMPEygPOSBdsIoT13cmSHY |isbn=0805066381 |pages=436 |quote=''At least a million-and-a-half more disappeared into the newly established 'reform through labour' camps, purpose-built to accommodate them.''}}</ref> Mao’s personal role in ordering mass executions is undeniable.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.laogai.org/news/newsdetail.php?id=2392|title=Commentary transferred to Huang Jing regarding the supplementary plan to suppress counterrevolutionaries in Tianjin}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://hrichina.org/public/PDFs/CRF.4.2005/CRF-2005-4_Quota.pdf|title=Mao's "Killing Quotas."] Human Rights in China (HRIC). 26 September 2005, at Shandong University|last=Changyu|first=Li}}</ref> He defended these killings as necessary for the securing of power.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/chinesehistory/pgp/jeremy50sessay.htm|title=''Terrible Honeymoon: Struggling with the Problem of Terror in Early 1950s China.''|last=Brown|first=Jeremy}}</ref> |

|||

Following the consolidation of power, Mao launched the First Five-Year Plan (1953-8). The plan aimed to end Chinese dependence upon agriculture in order to become a world power. With the [[USSR]]'s assistance, new industrial plants were built and agricultural production eventually fell to a point where industry was beginning to produce enough capital that China no longer needed the USSR's support. The success of the First Five Year Plan was to encourage Mao to instigate the Second Five Year Plan, the Great Leap Forward, in 1958. Mao also launched a phase of rapid [[collectivization]]. The CPC introduced price controls as well as a [[Simplified Chinese character|Chinese character simplification]] aimed at increasing literacy. Land was taken from landlords and more wealthy peasants and given to poorer peasants. Large scale industrialization projects were also undertaken. |

|||

Programs pursued during this time include the [[Hundred Flowers Campaign]], in which Mao indicated his supposed willingness to consider different opinions about how China should be governed. Given the freedom to express themselves, liberal and intellectual Chinese began opposing the Communist Party and questioning its leadership. This was initially tolerated and encouraged. After a few months, Mao's government reversed its policy and persecuted those, totalling perhaps 500,000, who criticized, and were merely alleged to have criticized, the Party in what is called the [[Anti-Rightist Movement]]. Authors such as [[Jung Chang]] have alleged that the Hundred Flowers Campaign was merely a ruse to root out "dangerous" thinking.<ref>Chang, Jung; Halliday, Jon. 2005. ''Mao: The Unknown Story''. New York: Knopf. 410. </ref> Others such as Dr [[Li Zhisui]] have suggested that Mao had initially seen the policy as a way of weakening those within his party who opposed him, but was surprised by the extent of criticism and the fact that it began to be directed at his own leadership.{{Fact|date=January 2007}} It was only then that he used it as a method of identifying and subsequently persecuting those critical of his government. The Hundred Flowers movement led to the condemnation, silencing, and death of many citizens, also linked to Mao's Anti-Rightist Movement, with death tolls possibly in the millions. |

|||

===Great Leap Forward=== |

|||

{{Main|Great Leap Forward}} |

|||

In January 1958, Mao launched the second Five-Year Plan known as the ''[[Great Leap Forward]]'', a plan intended as an alternative model for economic growth to the Soviet model focusing on heavy industry that was advocated by others in the party. Under this economic program, the relatively small agricultural collectives which had been formed to date were rapidly merged into far larger [[people's communes]], and many of the peasants ordered to work on massive infrastructure projects and the small-scale production of iron and steel. All private food production was banned; livestock and farm implements were brought under collective ownership. |

|||

Under the Great Leap Forward, Mao and other party leaders ordered the implementation of a variety of unproven and unscientific new agricultural techniques by the new communes. Combined with the diversion of labor to steel production and infrastructure projects and the reduced personal incentives under a commune system this led to an approximately 15% drop in grain production in 1959 followed by further 10% reduction in 1960 and no recovery in 1961. In an effort to win favor with their superiors and avoid being purged, each layer in the party hierarchy exaggerated the amount of grain produced under them and based on the fabricated success, party cadres were ordered to requisition a disproportionately high amount of the true harvest for state use primarily in the cities and urban areas but also for export. The net result, which was compounded in some areas by drought and in others by floods, was that the rural peasants were not left enough to eat and many millions starved to death in what is thought to be the largest [[famine]] in [[human history]]. This famine was a direct cause of the death of tens of millions of Chinese peasants between 1959 and 1962. Further, many children who became emaciated and malnourished during years of hardship and struggle for survival, died shortly after the Great Leap Forward came to an end in 1962 (Spence, 553). |

|||

The extent of Mao's knowledge as to the severity of the situation has been disputed. According to some, most notably Dr. Li Zhisui, Mao was not aware of anything more than a mild food and general supply shortage until late 1959. |

|||

:''"But I do not think that when he spoke on 2 July 1959, he knew how bad the disaster had become, and he believed the party was doing everything it could to manage the situation"'' |

|||

Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, in ''Mao: the Unknown Story'', alleged that Mao knew of the vast suffering and that he was dismissive of it, blaming bad weather or other officials for the famine. |

|||

:''"Although slaughter was not his purpose with the Leap, he was more than ready for myriad deaths to result, and hinted to his top echelon that they should not be too shocked if they happened (438-439)."'' |

|||

Whatever the case, the Great Leap Forward led to millions of deaths in China. Mao lost esteem among many of the top party cadres and was eventually forced to abandon the policy in 1962, also losing some political power to moderate leaders, notably [[Liu Shaoqi]] and [[Deng Xiaoping]]. However, Mao and national propaganda claimed that he was only partly to blame. As a result, he was able to remain Chairman of the Communist Party, with the Presidency transferred to Liu Shaoqi. |

|||

The Great Leap Forward was a disaster for China. Although the steel quotas were officially reached, almost all of it made in the countryside was useless lumps of iron, as it had been made from assorted scrap metal in home made furnaces with no reliable source of fuel such as coal. According to Zhang Rongmei, a geometry teacher in rural Shanghai during the Great Leap Forward: |

|||

:''We took all the furniture, pots, and pans we had in our house, and all our neighbors did likewise. We put all everything in a big fire and melted down all the metal.'' |

|||

Moreover, most of the dams, canals and other infrastructure projects, which millions of peasants and prisoners had been forced to toil on and in many cases die for, proved useless as they had been built without the input of trained engineers, whom Mao had rejected on ideological grounds. |

|||

[[Image:Kissinger Mao.jpg|thumb|Mao, shown here with [[Henry Kissinger]] and [[Zhou Enlai]]; [[Beijing]], 1972.]] |

|||

In the Party Congress at [[Lushan]] in July/August 1959, several leaders expressed concern that the ''Great Leap Forward'' was not as successful as planned. The most direct of these was Minister of Defence and [[Korean War]] General [[Peng Dehuai]]. Mao, fearing loss of his position, orchestrated a purge of Peng and his supporters, stifling criticism of the Great Leap policies. |

|||

There is a great deal of controversy over the number of deaths by starvation during the Great Leap Forward. Until the mid 1980s, when official census figures were finally published by the Chinese Government, little was known about the scale of the disaster in the Chinese countryside, as the handful of Western observers allowed access during this time had been restricted to model villages where they were deceived into believing that Great Leap Forward had been a great success. There was also an assumption that the flow of individual reports of starvation that had been reaching the West, primarily through Hong Kong and Taiwan, must be localized or exaggerated as China was continuing to claim record harvests and was a net exporter of grain through the period. Censuses were carried out in China in 1953, 1964 and 1982. The first attempt to analyse this data in order to estimate the number of famine deaths was carried out by American demographer Dr Judith Banister and published in 1984. Given the lengthy gaps between the censuses and doubts over the reliability of the data, an accurate figure is difficult to ascertain. Nevertheless, Banister concluded that the official data implied that around 15 million excess deaths incurred in China during 1958-61 and that based on her modelling of Chinese demographics during the period and taking account of assumed underreporting during the famine years, the figure was around 30 million. The official statistic is 20 million deaths, as given by [[Hu Yaobang]].<ref name="Short, 761"/> Various other sources have put the figure between 20 and 72 million.<ref name = "maostats"/> |

|||

On the international front, the period was dominated by the further isolation of China, due to start of the [[Sino-Soviet split]] which resulted in [[Khrushchev]] withdrawing all Soviet technical experts and aid from the country. The split was triggered by border disputes, and arguments over the control and direction of world communism, and other disputes pertaining to foreign policy. Most of the problems regarding communist unity resulted from the death of Stalin and his replacement by Khrushchev. Stalin had established himself as the successor of "correct" Marxist thought well before Mao controlled the [[Communist Party of China]], and therefore Mao never challenged the suitability of any Stalinist doctrine (at least while Stalin was alive). Upon the death of Stalin, Mao believed (perhaps because of seniority) that the leadership of the "correct" Marxist doctrine would fall to him. The resulting tension between Khrushchev (at the head of a politically/militarily superior government), and Mao (believing he had a superior understanding of Marxist ideology) eroded the previous patron-client relationship between the [[CPSU]] and CPC. In China, the formerly favourable Soviets were now denounced as "revisionists" and listed alongside "American imperialism" as movements to oppose. |

|||

[[Image:Che-mao.jpg|thumb|left|[[Che Guevara]] being received in China by Mao, at an official ceremony in the Government palace, November 1960]] |

|||

Partly-surrounded by hostile [[United States|American]] military bases (reaching from [[South Korea]], [[Japan]], [[Okinawa]], and [[Taiwan]]), China was now confronted with a new [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] threat from the north and west. Both the internal crisis and the external threat called for extraordinary statesmanship from Mao, but as China entered the new decade the statesmen of the People's Republic were in hostile confrontation with each other. |

|||

At a large Communist Party conference in Beijing in January 1962, called the "Conference of the Seven Thousand," [[President of the People's Republic of China|State President]] [[Liu Shaoqi]] denounced the Great Leap Forward as responsible for widespread famine.<ref name="Chang">Chang, Jung and Jon Halliday, ''Mao: The Unknown Story'' (2006), pp. 568, 579.</ref> The overwhelming majority of delegates expressed agreement, but Defense Minister [[Lin Biao]] staunchly defended Mao.<ref name="Chang"/> A brief period of liberalization followed while Mao and Lin plotted a comeback.<ref name="Chang"/> Liu and [[Deng Xiaoping]] rescued the economy by disbanding the people's communes, introducing elements of private control of peasant smallholdings and importing grain from Canada and Australia to mitigate the worst effects of famine. |

|||

===Cultural Revolution=== |

|||

{{Main|Cultural Revolution}} |

|||

[[Liu Shaoqi]] and [[Deng Xiaoping]]'s prominence gradually became a challenge to Mao's position of power. Liu and Deng, then the State President and General Secretary, respectively, had favored the idea that Mao should be removed from actual power but maintain his ceremonial and symbolic role, and the party will uphold all of his positive contributions to the revolution. They attempted to marginalize Mao by taking control of economic policy and asserting themselves politically as well. |

|||

Facing the prospect of losing his place on the political stage, Mao responded to Liu and Deng's movements by launching the [[Cultural Revolution]] in 1966. Under the pretext that certain liberal "bourgeois" elements of society, labeled as class enemies, continue to threaten the socialist framework under the existing dictatorship of the proletariat, the idea that a Cultural Revolution must continue after armed struggle allowed Mao to circumvent the Communist hierarchy by giving power directly to the [[Red Guard (China)|Red Guards]], groups of young people, often teenagers, who set up their own tribunals. Chaos reigned over the country, and millions were prosecuted, including a famous philosopher, Chen Yuen. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao closed the schools in China and the young intellectuals living in cities were ordered to the countryside. They were forced to manufacture weapons for the Red Army. The Revolution led to the destruction of much of China's cultural heritage and the imprisonment of a huge number of Chinese citizens, as well as creating general economic and social chaos in the country. Millions of lives were ruined during this period, as the Cultural Revolution pierced into every part of Chinese life, depicted by such Chinese [[film]]s as ''[[To Live (film)|To Live]]'', ''[[The Blue Kite]]'' and ''[[Farewell My Concubine (film)|Farewell My Concubine]]''. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, perished in the violence of the Cultural Revolution.<ref name="maostats">{{cite web | url = http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat1.htm#Mao |title=Source List and Detailed Death Tolls for the Twentieth Century Hemoclysm | publisher = Historical Atlas of the Twentieth Century | accessdate=2008-08-23}}</ref> When Mao was informed of such losses, particularly that people had been driven to suicide, he blithely commented: ''"People who try to commit suicide — don't attempt to save them! . . . China is such a populous nation, it is not as if we cannot do without a few people."''<ref>{{citebook|authorlink=Roderick MacFarquhar|last=MacFarquhar|first=Roderick|coauthors=Schoenhals, Michael|title=Mao's Last Revolution|publisher=[[Harvard University Press]]|year=2006|isbn=0674023323|pages=p. 110}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Nixon Mao 1972-02-29.png|thumb|Mao greets United States President [[Richard Nixon]] during his [[1972 Nixon visit to China|visit to China in 1972]]]] |

|||

It was during this period that Mao chose [[Lin Biao]], who seemed to echo all of Mao's ideas, to become his successor. Mao and Lin Biao formed an alliance leading up to the Cultural Revolution in order for the purges to succeed. Mao needed Lin's clout for his plan to work. In return, Lin was made Mao's successor. By 1971, however, because of Lin's grip over the military and Mao's own paranoia, a divide between the two men became clear, and it was unclear whether Lin was planning a military coup or an assassination attempt. Lin Biao died trying to flee China, probably anticipating his arrest, in a suspicious plane crash over [[Mongolia]]. It was declared that Lin was planning to depose Mao, and he was posthumously expelled from the CPC. At this time, Mao lost trust in many of the top CPC figures. The highest-ranking Soviet Bloc intelligence defector, Lt. Gen. [[Ion Mihai Pacepa]] described his conversation with [[Nicolae Ceauşescu]] who told him about a plot to kill Mao Zedong with the help of [[Lin Biao]] organized by [[KGB]].<ref name="Pacepa0">{{citeweb|url=http://article.nationalreview.com/?q=MzY4NWU2ZjY3YWYxMDllNWQ5MjQ3ZGJmMzg3MmQyNjQ=|title=The Kremlin’s Killing Ways|author=Ion Mihai Pacepa|publisher=National Review Online|date=28 November 2006|accessdate=2008-08-23}}</ref> |

|||

In 1969, Mao declared the Cultural Revolution to be over, although the official history of the People's Republic of China marks the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 with Mao's death. In the last years of his life, Mao was faced with declining health due to either [[Parkinson's disease]] or, according to Li Zhisui, [[motor neurone disease]], as well as lung ailments due to [[tobacco smoking|smoking]] and [[heart disease|heart trouble]]. Mao remained passive as various factions within the Communist Party mobilized for the power struggle anticipated after his death. |

|||

==Mao Zedong's final days, Death== |

|||

At five o'clock in the afternoon of 2 September 1976, Mao suffered a heart attack, far more severe than his previous two and affecting a much larger area of his [[heart]]. His body was giving out. The personal doctors group began emergency treatment immediately. [[X rays]] indicated that his lung infection had worsened, and his urine output dropped to less than 300 cc a day. |

|||

Mao was awake and alert throughout the crisis and asked several times whether he was in danger. His condition continued to fluctuate and his life hung in the balance. Three days later, on 5 September Mao's condition was still critical, and [[Hua Guofeng]] called [[Jiang Qing]] back from her trip. She spent only a few moments in Building 202 (where Mao was staying) before returning to her own residence in the Spring Lotus Chamber. On the afternoon of 7 September, Mao took a turn for the worse. Jiang Qing came to Building 202 where she learned the bad news. Mao had just fallen asleep and needed the rest, but she insisted on rubbing his back and moving his limbs, and she sprinkled powder on his body. The medical team protested that the dust from the powder was not good for his lungs, but she instructed the nurses on duty to follow her example later. The next morning, 8 September, she came again. She wanted the medical staff to change Mao's sleeping position, claiming that he had been lying too long on his left side. The doctor on duty objected, knowing that he could breathe only on his left side, but she had him moved nonetheless. Mao's breathing stopped and his face turned blue. Jiang Qing left the room while the medical staff put him on a respirator and performed emergency [[cardiopulmonary resuscitation]]. Mao barely revived, and [[Hua Guofeng]] urged Jiang Qing not to interfere further with the doctor's work, as her actions were detrimental to Mao's health & death. Mao's organs were failing and he was taken off life support few minutes after midnight. September 9 was chosen because it was an easy day to remember. Mao had been in poor health for several years and had declined visibly for some months prior to his death. His body lay in state at the [[Great Hall of the People]]. A memorial service was held in [[Tiananmen Square]] on 18 September 1976. There was a three minute silence observed during this service. His body was later placed into the [[Mausoleum of Mao Zedong]], although he wished to be cremated and had been one of the first high-ranking officials to sign the "Proposal that all Central Leaders be Cremated after Death" in November 1956.<ref>{{cite news |first= |last= |authorlink= |coauthors= |title=China After Mao's Death: Nation of Rumor and Uncertainty |url= |quote=[[Hong Kong]], 5 October 1976. With no word on the fate of the body of Mao Tsetung, almost a month after his death, rumors are beginning to percolate in China, much as they did following the death of Prime Minister Chou En-lai... |publisher=[[New York Times]] |date=6 October 1976 |accessdate=2007-07-21 }}</ref> |

|||

==Cult of Mao== |

|||

Mao's figure is largely symbolic both in China and in the global communist movement as a whole. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao's already glorified image manifested into a [[personality cult]] that stretched into every part of Chinese life. Mao presented himself as an enemy of landowners, businessmen, and Western and American [[imperialism]], as well as an ally of impoverished peasants, farmers and workers. |

|||

At the 1958 Party congress in Chengdu, Mao expressed support for the idea of personality cults if they venerated figures who were genuinely worthy of adulation: |

|||

{{cquote|There are two kinds of personality cults. One is a healthy personality cult, that is, to worship men like Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin. Because they hold the truth in their hands. The other is a false personality cult, i.e. not analyzed and blind worship.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://library.thinkquest.org/26469/cultural-revolution/cult.html |title= Cult of Mao | publisher = library.thinkquest.org | accessdate= 2008-08-23 |quote= This remark of Mao seems to have elements of truth but it is false. He confuses the worship of truth with a personality cult, despite there being an essential difference between them. But this remark played a role in helping to promote the personality cult that gradually arose in the CCP.}}</ref>}} |

|||

In 1962, Mao proposed the Socialist Education Movement (SEM) in an attempt to educate the peasants to resist the temptations of [[feudalism]] and the sprouts of capitalism that he saw re-emerging in the countryside (due to Liu's economic reforms). Large quantities of politicized art were produced and circulated — with Mao at the centre. Numerous posters and musical compositions referred to Mao as "A red sun in the centre of our hearts" (我们心中的红太阳) and a "Savior of the people" (人民的大救星). |

|||

The Cult of Mao proved vital in starting the Cultural Revolution. China's youth had mostly been brought up during the Communist era, and they had been told to love Mao. Secondly, the younger people did not remember the immense starvation and suffering caused by Mao's Great Leap Forward and so did not know anything negative about Mao. Thus they were his greatest supporters. Their feelings for him were so strong that many followed his urge to challenge all established authority. |

|||

In October 1966, Mao's ''[[Quotations From Chairman Mao Tse-Tung]]'', which was known as the ''Little Red Book'' was published. Party members were encouraged to carry a copy with them and possession was almost mandatory as a criterion for membership. Over the years, Mao's image became displayed almost everywhere, present in homes, offices and shops. His quotations were [[Emphasis (typography)|typographically emphasized]] by putting them in boldface or red type in even the most obscure writings. Music from the period emphasized Mao's stature, as did children's rhymes. The phrase ''Long Live Chairman Mao for [[ten thousand years]]'' was commonly heard during the era, which was traditionally a phrase reserved for the reigning [[Emperor of China|Emperor]]. |

|||

After the Cultural Revolution, there are some people who still worship Mao in family altars or even temples for Mao.<ref>{{cite book |last=Lu |first=Xing |others=Contributor Thomas W. Benson |title=Rhetoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution |publisher=University of South Carolina Press |isbn=1570035431 |url=http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN1570035431 |pages=147 |quote= Some continue to worship Mao at their family altars, praying to him for peace and safety ... thousands of people visit the temple each day burning incense and kowtowing to images of Mao}}</ref> |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||