Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

| Charles V | |

|---|---|

| Holy Roman Emperor; King of Spain, Naples and Sicily, others | |

| |

| Reign | King of Spain File:Bandera de los Reyes Católicos.gif Holy Roman Emperor King of Naples Sovereign of the NetherlandsFile:Flag - Low Countries medium.png Count of Flanders Duke of Brabant Duke of Milan Duke of Luxembourg Duke of Burgundy |

| Coronation | 1516 |

| Predecessor | Joanna of Castile (Castile) Ferdinand II (Aragon & Naples) Maximilian I (Holy Roman Empire) Philip of Burgundy (Netherlands) |

| Successor | Philip II of Spain (Spain, Naples & Netherlands) Ferdinand I (Holy Roman Empire) |

| Issue | Philip II of Spain Maria of Spain Joan of Spain |

| House | House of Habsburg |

| Father | Philip of Burgundy |

| Mother | Joanna of Castile |

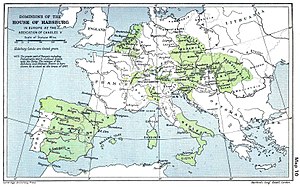

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was ruler of the Burgundian Netherlands (1506-1555), King of Spain (1516-1556), King of Naples and Sicily (1516-1554), Archduke of Austria (1519-1521), King of the Romans (or German King), (1519-1556 but did not formally abdicate until 1558) and Holy Roman Emperor (1530-1556 but did not formally abdicate until 1558). In Spain, though he is often referred to as Carlos V or Charles Quint, he ruled officially as Carlos I, Charles I of Spain.

He was the son of Philip the Handsome and Joanna the Mad of Castile. His maternal grandparents were Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, whose marriage had first united their territories into what is now modern Spain. His paternal grandparents were Emperor Maximilian I and Mary of Burgundy. His aunt was Catherine of Aragon, Queen of England and first wife of Henry VIII, his cousin was Mary I of England who married his son Philip.

Charles V's reign introduced the first documented use of the styles of His Majesty or His Imperial Majesty. Because of his far-reaching territories he was described as ruling an Empire "in which the sun does not set".

Heritage and early life

Combining in himself the heritage of the German Habsburgs, the House of Burgundy, and the Spanish heritage of his mother, Charles, transcended ethnic and national boundaries.

Charles was born in the Flemish city of Ghent and brought up in Mechelen by his aunt Margarete of Austria until 1517. The culture and courtly life of the Burgundian Low Countries were an important influence in his early life. He spoke French as mother language and Flemish from his childhoord years, later adding an acceptable Spanish (which was required by the Castilian Cortes as a condition for becoming king of Castile) and some German. [1] Indeed, he claimed to speak "Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men, and German to my horse."

From his Burgundian ancestors, he inherited an ambiguous relationship with the Kings of France. Charles shared with France his mother tongue and many cultural forms. In his youth, he made frequent visits to Paris, then the largest city of Western Europe. In his words: "Paris is not a city, but a universe" (Lutetia non urbs, sed orbis). But Charles also inherited the tradition of political and dynastical enemity between the Royal and the Burgundian lines of the Valois Dynasty. This conflict was amplified by his accession to both the Holy Roman Empire and the kingdom of Spain.

Though Spain was the core of his kingdom, he was never totally assimilated and especially in his earlier years felt like and was viewed as a foreign prince. He could not speak Spanish very well, as it was not his primary language. Nonetheless, he spent most of his life in Spain, including his final years in a Spanish monastery.

In his youth, Charles was tutored by Adrian of Utrecht, later Pope Adrian VI. His three most prominent subsequent advisors were Lord Chièvres, Jean Sauvage and Mercurino Gattinara.

Marriage and children

Template:House of Habsburg (Charles I arms)

On March 10, 1526, Charles married his first cousin Isabella of Portugal, sister of John III of Portugal.

Their children included:

- Philip II of Spain (1527 - 1598), the only son to reach adulthood.

- Maria of Spain (1528 - 1603), who married her cousin Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor.

- Joan of Spain (1535 - 1573)

Charles is also famous for his many mistresses. Two of them gave birth to two future Governors of the Habsburg Netherlands:

- Johanna Maria van der Gheynst bore Margaret of Parma and

- Barbara Blomberg bore John of Austria.

Reign

Burgundy and the Low Countries

In 1506, Charles inherited his father's Burgundian territories, most notably the Low Countries and Franche-Comté, although, as he was a minor, his aunt Margaret acted as regent until 1515.

Charles extended the Burgundian territory with the annexation of Tournai, Artois, Utrecht, Groningen and Guelders. The Seventeen Provinces had been unified by Charles' Burgundian ancestors, but nominally were fiefs of either France or the Holy Roman Empire. In 1549, Charles issued a Pragmatic Sanction, declaring the Low Countries to be a unified entity of which his family would be the heirs.[1]

The Low Countries held an important place in the Empire. For Charles personally, they were the region where he spent his childhood. Because of trade and industry and the rich cities, they were also important for the treasury.

Spain

With the death of his grandfather Ferdinand II on May 30 1516, Charles inherited his grandfather's realm, which included Aragon, Navarre, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia. He also became joint ruler of Castile with, and guardian of, his insane mother Joanna. With the Castilian crown he also gained Granada and the Spanish possessions in the New World.

For the first time the crowns of Castile and Aragon were united in one person. Ferdinand and Isabella had each been sovereign in one kingdom, but only consort in the other.

Charles arrived in his new kingdoms in autumn of 1517. His regent Jiménez de Cisneros came to meet him, but fell ill along the way, not without a suspicion of poison, and died before meeting the King.[2]

Negotiations with the Castilian Cortes proved difficult, and in the end Charles was accepted under the following conditions: he would learn to speak Castilian; he would not appoint foreigners; he was prohibited from taking precious metals from Castile; and he would respect the rights of his mother, Queen Joanna. The Cortes paid homage to him in Valladolid in 1518. In 1519, he was crowned before the Cortes of Aragon in Zaragoza, and the Corts of Catalonia followed.

Charles was accepted as sovereign, even though the Spanish felt uneasy with the Imperial style. Spanish monarchs until then had been bound by the laws; the monarchy was a contract with the people. With Charles it would become more absolute, even though until his mother's death in 1555 Charles did not hold the full kingship of the country.

Soon resistance against the Emperor rose, because of the heavy taxation (funds that were used to fight wars abroad, wars most Castilians had no interest in) and because Charles tended to select Flemings for high offices in Spain and America, ignoring Castilian candidates. The resistance culminated in the Castilian War of the Communities, which was suppressed by Charles. After this, Castile became integrated into the Habsburg empire, and would provide the bulk of the empire's military and financial resources.

| Silver 4 real coin of Carlos V, struck ca. 1542-1555 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse: CAROLVUS ET IOHANA, REGES (Charles and Johanna, Monarchs). Depicts the crest of Castile and León. The strike date was determined by the Assayer L. | Reverse: HISPANIARVM ET INDIARVM (Of the Spains [Spanish kingdoms] and the Indies." Depicts the Strait of Gibraltar between the Pillars of Hercules. Center Latin motto is PLVS VLTRA, or "Further Beyond." |

America

During Charles' reign, the territories in New Spain were considerably extended by conquistadores like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, who caused the Aztec and Inca empires to fall in little more than a decade. Combined with the Magellan expedition's circumnavigation of the globe in 1522, these successes convinced Charles of his divine mission to become the leader of a Christian world that still perceived a significant threat from Islam. Of course, the conquests also helped solidify Charles' rule by providing the state treasury with enormous amounts of bullion. As the conquistador Bernal Diaz observed: "We came to serve God and our Majesty, ... and also to get rich." [1] In 1550, Charles convened a conference at Valladolid in order to consider the morality of the force used against the indigenous populations of Spanish America.

Holy Roman Empire

After the death of his paternal grandfather, Maximilian, in 1519, he inherited the Habsburg lands in Austria. He was also the natural candidate to succeed of the electors, but with the help of the wealthy Fugger family Charles could oust Francis and was elected on June 28, 1519. In 1530, he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Clement VII in Bologna, the last Emperor to receive a papal coronation.

Charles was Holy Roman Emperor over the German states, but his real power was limited by the princes. Protestantism gained a lot of support in Germany, and Charles was determined not to let this happen in the Netherlands. An inquisition was established as early as 1522. In 1550, the death penalty was introduced for all heresy. Political dissent was also firmly controlled, most notably in his place of birth, where Charles personally suppressed the Revolt of Ghent in 1539.[1]

Wars against France

Much of Charles's reign was taken up with wars with France, which found itself encircled by Charles's empire and still maintained ambitions in Italy. The first war with Charles's great nemesis Francis I of France began in 1521. Charles allied with England and Pope Leo X against the French and the Venetians, and was highly successful, driving the French out of Milan and defeating and capturing Francis at the Battle of Pavia in 1525. To gain his freedom, the French king was forced to cede Burgundy to Charles in the humiliating Treaty of Madrid (1526).

When he was released, however, Francis had the Parlement of Paris denounce the treaty because it had been signed under duress. France then joined the League of Cognac that Pope had formed with Henry VIII of England, the Venetians, the Florentines, and the Milanese to resist imperial domination of Italy. In the ensuing war, Charles's sack of Rome (1527) and virtual imprisonment of Pope Clement VII in 1527 prevented him from annulling the marriage of Henry VIII of England and Charles's aunt Catherine of Aragon, with important consequences. In other respects, the war was inconclusive. In the Treaty of Cambrai (1529), called the "Ladies' Peace" because it was negotiated between Charles's aunt and Francis's mother, Francis renounced his claims in Italy but retained control of Burgundy.

A third war erupted in 1535, when, following the death of the last Sforza Duke of Milan, Charles installed his own son, Philip, in the duchy, despite Francis's claims on it. This war too was inconclusive. Francis failed to conquer Milan, but succeeded in conquering most of the lands of Charles's ally the Duke of Savoy, including his capital, Turin. A truce at Nice in 1538 on the basis of uti possidetis ended the war, but lasted only a short time. War resumed in 1542, with Francis now allied with Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I and Charles once again allied with Henry VIII. Despite the conquest of Nice by a Franco-Ottoman fleet, the French remained unable to advance into Milan, while a joint Anglo-Imperial invasion of northern France, led by Charles himself, won some successes but was ultimately abandoned, leading to another peace and restoration of the status quo ante in 1544.

A final war erupted with Francis's son and successor, Henry II, in 1551. This war saw early successes by Henry in Lorraine, where he captured Metz, but continued failure of French offensives in Italy. Charles abdicated midway through this conflict, leaving further conduct of the war to his son, Philip II and his brother, Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor.

Wars against the Ottoman Empire

Charles fought continually with the Ottoman Empire and its sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, for a number of years. The expeditions of the Ottoman force along the Mediterranean coast posed a threat to Habsburg lands and Christian monopolies on trade in the Mediterranean. In Central Europe, the Turkish advance was halted at Vienna in 1529. In 1535 Charles won an important victory at Tunis, but in 1536 Francis I of France allied himself with Suleiman against Charles. While Francis was persuaded to sign a peace treaty in 1538, he again allied himself with the Ottomans in 1542. In 1543 Charles allied himself with Henry VIII and forced Francis to sign the Truce of Crepy-en-Laonnois. Charles later signed a humiliating treaty with the Ottomans, to gain him some respite from the huge expenses of their war, although it wasn't over. However, the Protestant powers in the Holy Roman Empire Diet often voted against money for his Turkish wars, as many Protestants saw the Muslim advance as a counterweight to the Catholic powers. The great Hungarian defeat at the 1526 Battle of Mohacs was in some ways a moral defeat for the West as a whole [citation needed].

Humanism and Reformation

As Holy Roman Emperor, he called Martin Luther to the Diet of Worms in 1521, promising him safe conduct if he would appear. He initially dismissed Luther's idea of reformation as, "An argument between monks". He later outlawed Luther and his followers in that same year but was tied up with other concerns and unable to try to stamp out Protestantism.

1524 to 1526 saw the Peasants' Revolt in Germany and the formation of the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League, and Charles delegated increasing responsibility for Germany to his brother Ferdinand while he concentrated on problems abroad.

In 1545, the opening of the Council of Trent began the Counter-Reformation, and Charles won to the Catholic cause some of the princes of the Holy Roman Empire. He also attacked the Schmalkaldic League in 1546 and at the Battle of Mühlberg defeated John Frederick, Elector of Saxony and imprisoned Philip of Hesse in 1547. At the Augsburg Interim in 1548 he created a doctrinal compromise that he felt Catholics and Protestants alike might share. A more permanent settlement followed with the 1555 Peace of Augsburg.

Abdication and later life

Template:Commons2 In 1556, Charles abdicated his various titles, giving his Spanish empire (Spain, the Netherlands, Naples and Spain's posessions in the Americas) to his son, Philip II of Spain. He passed his dynastic Austrian lands and the Holy Roman Empire to his brother, Ferdinand. Charles retired to the monastery of Yuste in Extremadura, but continued to correspond widely and kept an interest in the situation of the empire. He suffered from severe gout and some scholars think Charles V decided to abdicate after a gout attack in 1552 forced him to postpone an attempt to recapture the city of Metz, where he was later defeated.[3].

Charles died on September 21, 1558. Twenty-six years later, his remains were transferred to the Royal Pantheon of The Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial.

Trivia

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. |

- He suffered from an enlarged lower jaw, a deformity which got considerably worse in later Habsburg generations. He struggled to chew his food properly and consequently experienced bad indigestion for much of his life. As a result, he usually ate alone.

- He suffered from joint pain, presumed to be gout, according to his 16th century doctors.[4]

- He was afraid of mice and spiders.

- He was obsessed with clocks and instructed his servants to take them apart and reassemble them in his presence.

- In his retirement, he was carried around the monastery of St. Yuste in a sedan chair. A ramp was specially constructed to allow him easy access to his rooms.

- He passed his time fishing from his window on the first floor and enjoying the smell of incense drifting on the breeze from the abbey church.

Ancestors

| Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor | Father: Philip I of Castile |

Paternal Grandfather: Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor |

Paternal Great-Grandfather: Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Paternal Great-Grandmother: Eleanor of Portugal, Empress | |||

| Paternal Grandmother: Mary of Burgundy |

Paternal Great-Grandfather: Charles the Bold | ||

| Paternal Great-Grandmother: Isabella of Bourbon | |||

| Mother: Joanna of Castile |

Maternal Grandfather: Ferdinand II of Aragon |

Maternal Great-Grandfather: John II of Aragon | |

| Maternal Great-Grandmother: Juana Enriquez | |||

| Maternal Grandmother: Isabella I of Castile |

Maternal Great-Grandfather: John II of Castile | ||

| Maternal Great-Grandmother: Infanta Isabel of Portugal |

References

- ^ a b c d Kamen, Henry (2005). Spain, 1469–1714: a society of conflict (3rd ed.). Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education. 0-582-78464-6.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911 edition.

- ^ "The Severe Gout of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V", from the The New England Journal of Medicine, 355:516–520 August 3 2006

- ^ "Tests confirm old emperor's gout diagnosis." The Record. August 4, 2006, Nation.

Bibliography

- Template:De icon Norbert Conrads: Die Abdankung Kaiser Karls V. Abschiedsvorlesung, Universität Stuttgart, 2003 (text)

- Template:De icon Stephan Diller, Joachim Andraschke, Martin Brecht: Kaiser Karl V. und seine Zeit. Ausstellungskatalog. Universitäts-Verlag, Bamberg 2000, ISBN 3-933463-06-8

- Template:De icon Alfred Kohler: Karl V. 1500–1558. Eine Biographie. C. H. Beck, München 2001, ISBN 3-406-45359-7

- Template:De icon Alfred Kohler: Quellen zur Geschichte Karls V. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-04820-2

- Template:De icon Alfred Kohler, Barbara Haider. Christine Ortner (Hrsg): Karl V. 1500–1558. Neue Perspektiven seiner Herrschaft in Europa und Übersee. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien 2002, ISBN 3-7001-3054-6

- Template:De icon Ernst Schulin: Kaiser Karl V. Geschichte eines übergroßen Wirkungsbereichs. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-17-015695-0

- Template:De icon Ferdinant Seibt: Karl V. Goldmann, München 1999, ISBN 3-442-75511-5

- Template:De icon Manuel Fernández Álvarez: Imperator mundi: Karl V. – Kaiser des Heiligen Römischen Reiches Deutscher Nation.. Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3763011781

- Holy Roman emperors

- German kings

- Spanish monarchs

- Roman Catholic monarchs

- Kings of Sicily

- Monarchs of Naples

- House of Habsburg

- Rulers of Austria

- Rulers of Styria

- Dukes of Carinthia

- Dukes of Brabant

- Dukes of Guelders

- Dukes of Lothier

- Dukes of Luxembourg

- Dukes of Milan

- Counts of Tyrol

- Counts of Flanders

- Counts of Hainaut

- Counts of Holland

- Princes of Asturias

- Knights of the Garter

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- People from Ghent

- Martin Luther

- 1500 births

- 1558 deaths