Billy the Kid

Henry McCarty a.k.a. William H. Bonney a.k.a. Billy the Kid | |

|---|---|

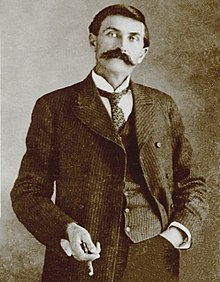

Billy the Kid. (Reversed ferrotype photograph) | |

| Born | November 23, 1859 |

| Died | July 14, 1881 (aged 21) |

| Occupation | Outlaw |

| Parent(s) | Natural Father: not known, poss. Patrick Henry McCarty or William Bonney Stepfather: William Antrim |

Henry McCarty (November 23, 1859[1] – July 14, 1881), better known as Billy the Kid, but also known by the aliases Henry Antrim and William H. Bonney, was a famous 19th century American frontier outlaw and gunman who was a participant in the Lincoln County War. According to legend, he killed 21 men, one for each year of his life, but more likely he participated in the killing of less than half that number.[2]

McCarty (or Bonney, the name he used at the height of his notoriety) was 5'8"-5'9" (173-175 cm) with blue eyes, smooth cheeks, and prominent front teeth.[3][4] He was said to be friendly and personable at times,[5][3] and many recalled that he was as "lithe as a cat".[3] Some contemporaries described him as a "neat" dresser who favored an "unadorned Mexican sombrero".[3] These qualities, along with his cunning and celebrated skill with firearms, contributed to his paradoxical image, as both a notorious outlaw and beloved folk hero.[6]

A relative unknown during his own lifetime, he was catapulted into legend the year after his death when his killer, Sheriff Patrick Garrett, published a sensationalistic biography titled The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid. Beginning with Garrett's account, Billy the Kid grew into a symbolic figure of the American Old West.[7]

Biography

Early life

Little is known about McCarty's background, but most reputable scholars of western history agree that he "was born on the eve of the Civil War in the bowels of an Irish neighborhood in New York City".[8] While his biological father remains an obscure figure, some researchers have theorized that his name was Patrick McCarty, Michael McCarty, William McCarty, or Edward McCarty.[8] There is clear evidence that his mother's name was Catherine McCarty, although "there have been continuing debates about whether McCarty was her maiden or married name".[8] It is generally believed that McCarty's parents were survivors of the Great Irish Famine of the mid-19th century.[8] Some genealogists argue, however, that the future outlaw was born William Henry Bonney, the son of William Harrison Bonney and wife Katherine Boujean, paternal grandson of Levi Bonney and wife Rhoda Pratt and great-grandson of Obadiah Pratt, who in turn were the grandparents of Mormon leader Parley P. Pratt, making him and McCarty first cousins once removed.[9] Furthermore, the late New Mexico historian, Herman P. Weisner, contended that McCarty was of partial Hispanic ancestry. Weisner's theory was based, in part, on the outlaw's remarkable fluency in Spanish and his well-known sympathy for the Hispanic people of the New Mexico Territory.[10]

By 1868, Catherine McCarty had relocated with her two young sons, Henry and Joseph, to Indianapolis, Indiana.[11] There, she met William Antrim, who was 12 years her junior.[12] In 1873, after several years of moving around the country, the couple married and settled in Silver City, New Mexico.[13] Antrim found sporadic work as a bartender and carpenter but soon became more interested in prospecting and gambling for fortune than in his wife and stepsons.[14] Despite this, young McCarty often used the surname "Antrim" when referring to himself.[15]

Faced with a husband who was frequently absent, McCarty's mother supposedly washed clothes, baked pies, and took in boarders in order to provide for her sons.[16] Although she was fondly remembered by onetime boarders and neighbors as "a jolly Irish lady, full of life and mischief", she was afflicted with tuberculosis.[17] The following year, on September 16, 1874, Catherine McCarty died; she was buried in the Memory Lane Cemetery in Silver City.[14] At age 14, McCarty was taken in by a neighboring family who operated a hotel where he worked to pay for his keep. The manager was impressed by the youth, contending that he was the only young man who ever worked for him that did not steal anything.[18] One of McCarty's school teachers later recalled that the young orphan was "no more of a problem than any other boy, always quite willing to help with chores around the schoolhouse".[19] Early biographers sought to explain McCarty's subsequent descent into lawlessness by focusing on his habit of reading dime novels that romanticized crime. A more likely explanation, however, was his slender physique, "which placed him in precarious situations with bigger and stronger boys".[20]

Forced to seek new lodgings when his foster family began to experience "domestic problems", McCarty moved into a boardinghouse and pursued odd jobs.[20] On September 24, 1875, McCarty was arrested when he was found to be in possession of clothing and firearms that a fellow boarder had stolen from a Chinese laundry owner.[21] Two days after McCarty was thrown in jail, the teenager escaped by worming his way up the jailhouse chimney. From that point on, McCarty was more or less a fugitive.[22] According to some accounts, he eventually found work as an itinerant ranch hand and shepherd in southeastern Arizona.[23] In 1876, he settled in the vicinity of Fort Grant Army Post in Arizona, where he worked local ranches and tested his skills at local gaming houses.[24]

During this time, McCarty became acquainted with John R. Mackie, a Scottish-born ex-cavalry private with a criminal bent.[25] The two men supposedly became involved in the risky, but profitable, enterprise of horse thievery; and McCarty, who targeted local soldiers, became known by the sobriquet of "Kid Atrim".[26] In 1877, McCarty became involved in an altercation with the civilian blacksmith at Fort Grant, a loquacious Irish immigrant named Frank "Windy" Cahill, who took pleasure in bullying young McCarty.[27] On August 17, Cahill reportedly attacked McCarty after a verbal exchange and threw him to the ground. Reliable accounts suggest McCarty retaliated by drawing his gun and shooting Cahill, who died the next day.[28] Years later, Louis Abraham, who knew McCarty in Silver City, denied that anyone was killed in an altercation.[29] Records show, however, that a coroner's inquest concluded that Cahill's shooting was "criminal and justifiable. Some of those who witnessed the incident later claimed that McCarty acted in self-defense.[30]

Fearful of Cahill's friends and associates, McCarty promptly fled Arizona Territory and entered New Mexico Territory.[31] He eventually arrived at the former army post of Apache Tejo, where he joined a band of cattle rustlers who targeted the massive herds of cattle magnate John Chisum.[32] During this period, McCarty was spotted by a resident of Silver City, and the teenager's involvement with the notorious gang was mentioned in a local newspaper.[33]

It is unclear how long McCarty rode with the gang of rustlers known as "the Boys".[34] He next turned up in the house of Heiskell Jones in Pecos Valley, New Mexico. Apaches had stolen McCarty's horse, which forced him to walk many miles to the nearest settlement, which was the Jones's home. She nursed the young man, who was near death, back to health.[35] The Jones family developed a strong attachment to McCarty and gave him one of their horses.[36] At some point in 1877, McCarty began to refer to himself as "Willam H. Bonney".[37]

Lincoln County War

In the Autumn of 1877, Bonney (McCarty) moved to Lincoln County, New Mexico, and was first hired by Doc Scurlock and Charlie Bowdre to work in their cheese factory.[citation needed] He met through them Frank Coe, George Coe and Ab Saunders, three cousins who owned their own ranch near to the ranch of Dick Brewer. After a short stint working on the ranch of Henry Hooker, Bonney began working on the Coe/Saunders ranch.[citation needed]

Late in 1877, along with Brewer, Bowdre, Scurlock, the Coe's and Saunders, Bonney was hired as a cattle guard by John Tunstall, an English cattle rancher, banker and merchant, and his partner, Alexander McSween, a prominent lawyer.[38] A conflict, known later as the Lincoln County War, had begun between the established town merchants, Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan and the ranchers.[39] Events turned bloody on February 18, 1878, when Tunstall, unarmed, was caught on an open range while herding cattle and murdered by William Morton, Jessie Evans, Tom Hill and Frank Baker.[40] Tunstall's murder enraged Bonney and the other ranch hands.[41]

They formed their own group called the Regulators, led by ranch hand Richard "Dick" Brewer, and proceeded to hunt down two of the members of the posse that had killed Tunstall. They captured Bill Morton and Frank Baker on March 6 and killed them on March 9 near Agua Negra. The same day they killed Morton and Baker, Jessie Evans and Tom Hill were involved in a shootout with a farmer they were harassing, resulting in Evans being wounded and Hill being killed. While returning to Lincoln they also killed one of their own members, a man named McCloskey, whom they suspected of being a traitor.[42]

On April 1, Regulators Jim French, Frank McNab, John Middleton, Fred Waite, Henry Brown and Bonney ambushed Sheriff William J. Brady[43] and his deputy, George W. Hindman, [44] killing them both in the high street of Lincoln itself. Bonney was wounded while trying to retrieve a rifle belonging to him, which Brady had taken in an earlier arrest.[42]

On April 4, in what would become known as the Gunfight of Blazer's Mills, they tracked down and killed an old buffalo hunter known as Buckshot Roberts, whom they suspected of involvement in the Tunstall murder, but not before Roberts shot and killed Dick Brewer, who had been the Regulators' leader up until that point. Four other Regulators were wounded during the gun battle, which took place at Blazer's Mill.[42]

Killing of Frank McNab and after

After Brewer's death, Frank McNab was elected captain of the Regulators. On April 29, 1878, a posse including the Jessie Evans Gang and the Seven Rivers Warriors, under the direction of Sheriff Peppin, engaged Regulators Frank McNab, Ab Saunders and Frank Coe in a shootout at the Fritz Ranch. McNab was killed in a hail of gunfire, with Saunders being badly wounded, and Frank Coe captured. On April 30, Seven Rivers members Tom Green, Charles Marshall, Jim Patterson and John Galvin were killed in Lincoln, and although the Regulators were blamed, that was never proven, and there were feuds going inside the Seven Rivers Warriors at that time. Frank Coe escaped custody some time after his capture, although it is not clear exactly when, allegedly with the assistance of Deputy Sheriff Wallace Olinger, who also gave him a pistol.

What is known about the morning following McNab's death is that the Regulator "iron clad" took up defensive positions in the town of Lincoln, trading shots with Dolan men as well as U.S. cavalrymen. The only casualty was Dutch Charley Kruling, a Dolan man wounded by a rifle slug fired by George Coe at a distance of 440 yards (400 m). By shooting at government troops, the Regulators gained their animosity and a whole new set of enemies. Around the time of Segovia's death, the Regulator "iron clad" gained a new member, a young Texas cowpoke named Tom O'Folliard, who would become Billy the Kid's best friend and constant sidekick. On May 15, the Regulators tracked down Seven Rivers gang member Manuel Segovia, who is believed to have shot McNab, with him being gunned down by Billy the Kid and Josefita Chavez.

Under indictment for the Brady killing, Bonney and the other Regulators spent the next several months in hiding and were trapped, along with McSween, in McSween's home in Lincoln on July 15, by members of "The House" and some of Brady's men. After a five-day siege, McSween's house was set on fire. Bonney and the other Regulators fled, Bonney killing a "House" member named Bob Beckwith in the process and maybe more. McSween was shot down while fleeing the blaze, and his death essentially marked the end of the Lincoln County Cattle War.

Lew Wallace and amnesty

In the Autumn of 1878, former Union Army General Lew Wallace became Governor of the New Mexico Territory. In order to restore peace to Lincoln County, Wallace proclaimed an amnesty for any man involved in the Lincoln County War who was not already under indictment. Bonney, who had fled to Texas after escaping from McSween's house, was under indictment, but Wallace was intrigued by rumors that the young man was willing to surrender himself and testify against other combatants if amnesty could be extended to him. In March 1879 Wallace and Bonney met in Lincoln County to discuss the possibility of a deal. True to form, Bonney greeted the governor with a revolver in one hand and a Winchester rifle in the other. After taking several days to consider Wallace's offer, Bonney agreed to testify in return for amnesty.

The arrangement called for Bonney to submit to a token arrest and a short stay in jail until the conclusion of his courtroom testimony. Although Bonney's testimony helped to indict John Dolan, the district attorney, one of the powerful "House" faction leaders, disregarded Wallace's order to set Bonney free after testifying. He was returned to jail in June 1879, but slipped out of his handcuffs and fled.

For the next year and a half, Bonney survived by rustling, gambling and killing. In January 1880, during a well-documented altercation, he killed a man named Joe Grant in a Fort Sumner saloon. Grant was boasting that he would kill the "Kid" if he saw him, not realizing the man he was playing poker with was "Billy the Kid." In those days people only loaded their revolvers with five bullets,[citation needed] since there were no safeties and a lot of accidents. The "Kid" asked Grant if he could see his ivory handled revolver and, while looking at the weapon, cycled the cylinder so the hammer would fall on the empty chamber. He then let Grant know who he was. When Grant fired, nothing happened, and Bonney then shot him. When asked about the incident later, he remarked, "It was a game for two, and I got there first". Other stories tell the bullet issue differently. One version is that Billy emptied the gun. Another story tells that Grant just bought the six shot from another man, Chisum cowboy Jack Finan, who just some hours before had shot three rounds without reloading. Grant hadn't reloaded the weapon either, as he didn't know about that. The Kid only turned the empty cartridges up to the hammer.

In November 1880, a posse pursued and trapped Bonney's gang inside a ranch house (owned by friend James Greathouse at Anton Chico in the White Oaks area). A posse member named James Carlysle[45] ventured into the house under white flag in an attempt to negotiate the group's surrender, with Greathouse being sent out as a hostage for the posse. At some point in the night it became apparent to Carlysle that the outlaws were stalling, when suddenly a shot was accidentally fired from outside. Carlysle, assuming the posse members had shot Greathouse, decided to run for his life, crashing through a window into the snow outside. As he did so, the posse, mistaking Carlysle for one of the gang, fired and killed him. Realizing what they had done and now demoralized, the posse scattered, allowing Bonney and his gang to slip away. Bonney later wrote to Governor Wallace claiming innocence in the killing of Carlysle and of involvement in cattle rustling in general.

Pat Garrett

During this time, the Kid also developed a friendship with an ambitious local bartender and former buffalo hunter named Pat Garrett. Running on a pledge to rid the area of rustlers, Garrett was elected as sheriff of Lincoln County in November 1880, and in early December he put together a posse and set out to arrest Bonney, now known almost exclusively as Billy the Kid, and carrying a $500 bounty on his head.

The posse led by Garrett fared much better, and his men closed in quickly. On December 19, Bonney barely escaped the posse's midnight ambush in Fort Sumner, during which one of the gang, Tom O'Folliard, was shot and killed. On December 23, he was tracked to an abandoned stone building located in a remote location called Stinking Springs. While Bonney and his gang were asleep inside, Garrett's posse surrounded the building and waited for sunrise. The next morning, a cattle rustler named Charlie Bowdre stepped outside to feed his horse. Mistaken for Bonney, he was killed by the posse. Soon afterward somebody from within the building reached for the horse's halter rope, but Garrett shot and killed the horse, the body of which then blocked the only exit. As the lawmen began to cook breakfast over an open fire, Garrett and Bonney engaged in a friendly exchange, with Garrett inviting Bonney outside to eat, and Bonney inviting Garrett to "go to hell." Realizing that they had no hope of escape, the besieged and hungry outlaws finally surrendered later that day and were allowed to join in the meal.

Escape from Lincoln

Bonney was jailed in the town of Mesilla while waiting for his April 1881 trial and spent his time giving newspaper interviews and also peppering Governor Wallace with letters seeking clemency. Wallace, however, refused to intervene. Bonney's trial took one day and resulted in his conviction for the murder of Sheriff Brady: the only conviction ever secured against any of the combatants in the Lincoln County Cattle War. On April 13, he was sentenced by Judge Warren Bristol to hang. The execution was scheduled for May 13, and he was sent to Lincoln to await this date, held under guard by two of Garrett's deputies, James Bell and Robert Ollinger, on the top floor of the town's courthouse. On April 28, while Garrett was out of town, Bonney stunned the territory by killing both of his guards and escaping.

The details of the escape are unclear. Some historians believe that a friend or Regulator sympathizer left a pistol in a nearby privy that Bonney was allowed to use, under escort, each day. Bonney then retrieved this gun and after Bell had led him back to the courthouse, turned it on his guard as the two of them reached the top of a flight of stairs inside. Another theory holds that Bonney slipped his manacles at the top of the stairs, struck Bell[46] over the head with them and then grabbed Bell's own gun and shot him.[42]

However it happened, Bell staggered out into the street and collapsed, mortally wounded. Meanwhile, Bonney scooped up Ollinger's[47] ten-gauge double barrel shotgun and waited at the upstairs window for Ollinger, who had been across the street with some other prisoners, to come to Bell's aid. As Ollinger came running into view, Bonney leveled the shotgun at him, called out "Hello Bob!" and shot him dead. The townsfolk supposedly gave him an hour that he used to remove his leg iron. The hour was granted in thanks for his work as part of "The Regulators." After cutting his leg irons with an axe, the young outlaw borrowed (or stole) a horse and rode leisurely out of town, reportedly singing. The horse was returned two days later.

Death

Responding to rumors that Bonney was still lurking in the vicinity of Fort Sumner almost three months after his escape, Sheriff Garrett and two deputies set out on July 14, 1881, to question one of the town's residents, a friend of Bonney's named Pedro Maxwell (son of land baron Lucien Maxwell). Near midnight, as Garrett and Maxwell sat talking in Maxwell's darkened bedroom, Bonney unexpectedly entered the room. There are at least two versions of what happened next.

One version says that as the Kid entered, he could not recognize Garrett in the poor light. Bonney drew his pistol and backed away, asking "¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?" (Spanish for "Who is it? Who is it?"). Recognizing Bonney's voice, Garrett drew his own pistol and fired twice, the first bullet hitting Bonney just above his heart, killing him. In a second version, Bonney entered carrying a knife, evidently headed to a kitchen area. He noticed someone in the darkness, and uttered the words "¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?" at which point he was shot and killed in ambush style.

Although the popularity of the first story persists, and portrays Garrett in a better light, many historians contend that the second version is probably the accurate one.[48] A markedly different theory, in which Garrett and his posse set a trap for Bonney, has also been suggested, most recently being investigated in the Discovery Channel documentary "Billy the Kid: Unmasked." The theory contends that Garrett went to the bedroom of Pedro Maxwell's sister, Paulita, and tied up and gagged her in her bed. Paulita was an acquaintance of Billy the Kid, and the two had possibly considered getting married. When Bonney arrived, Garrett was waiting behind Paulita's bed and shot the Kid.

Henry McCarty, alias Henry Antrim, alias William H. Bonney, alias Billy the Kid, was buried the next day in Fort Sumner's old military cemetery, between his fallen companions Tom O'Folliard and Charlie Bowdre. A single tombstone was later erected over the graves, giving the three outlaws' names and with the word "Pals" also carved into it. The tombstone has been stolen and recovered three times since being placed in the 1940s, and the entire gravesite is now enclosed by a steel cage.[49]

Notoriety, fact vs reputation

As with many men of the old west dubbed gunfighters, Billy the Kid's reputation exaggerated the actual facts of gunfights in which he was involved. Despite being credited with the killing of 21 men in his lifetime, he is believed to have participated in the killing of only nine men. Five of them died during shootouts in which several of the "Regulators" took part (including the revenge killing of Sheriff Brady); Of the other four, two were in self-defense gunfights and the other two were the killings of Deputies Bell and Olinger during the Kid's jail escape.

He reportedly was cool under fire, as were many of the Regulators, but his reputation was often lofted above what actually took place in reality. For instance, when he and the other Regulators killed Sheriff Brady, the Kid has been alleged to have calmly walked over and picked up a rifle previously seized by Brady. In fact, this never happened, not in that manner. He did take the rifle back, that is certain, but in reality he ran over to where Brady lay, snatching up the rifle while under fire from Deputy Matthews, who wounded both him and Regulator Jim French.

He is often depicted as the "leader" of the Regulators, when in fact he never led them. Dick Brewer led them until his death, Frank McNab followed until he was killed less than a month later, with the final leader being Doc Scurlock. Of the Regulators, several had previously taken part in gunfights and lynchings together. Scurlock, Saunders, the Coe's and Bowdre had stormed the Lincoln jail on July 18, 1876, removing horse thief Jesus Largo, and hanging him outside of town. Frank Coe and Ab Saunders had, just prior to that, tracked down and shot and killed cattle rustler Nicas Meras, in the Baca Canyon. In later depictions the Regulators, with the exception of Bonney, are often portrayed as inexperienced, even bumbling, and looking to Bonney to lead the way, when in fact this was not the case.

Ironically, it would be the notoriety he received due to the Lincoln County War that ultimately would have a negative effect on his appeals for amnesty. While many of the Regulators were able to simply fade away, or due to them being little known they were able to obtain amnesty, Bonney was not. He negotiated with Wallace for amnesty, and had hoped to eventually receive it. But it never came to pass. His attempts were, also, hindered by his continued outlaw lifestyle following the end of the war, despite him committing no major crimes short of horse theft. By all accounts, the one depiction of Bonney aka Billy the Kid that does seem to stand the test of research, is that he was, by most accounts, extremely well liked. There are numerous accounts recorded by those who knew him that depict him as fun loving and jolly, articulate in both his writing and his speech, and loyal to those he cared for.[50]

Left-handed or right-handed?

While Billy the Kid was right-handed, it was widely assumed in the 20th century that he was left-handed. This belief stemmed from the fact that the only known photograph of Bonney, an undated ferrotype, shows him with a Model 1873 Winchester rifle in his right hand and a gun belt with a holster on his left side, where a left-handed person would typically wear a pistol. The belief became so entrenched that in 1958, a biographical film was made about Billy the Kid called The Left Handed Gun starring Paul Newman. Late in the 20th century, it was discovered that the familiar ferrotype was actually a reverse image. This version shows his Model 1873 Winchester with the loading port on the left side. All Model 1873s had the loading port on the right side, proving the image was reversed, and that he was, in fact, wearing his pistol on his right hip. Even though the image has been proven to be reversed, the idea of a left-handed Billy the Kid continues to widely circulate. Perhaps because many people heard both of these arguments and confused them, many hold the belief that Billy the Kid was ambidextrous. Many Billy the Kid sites describe him as such, and the idea of him being ambidextrous is still widely disputed.[51][52][53][50]

Personality traits by first hand accounts

- Frank Coe, who rode as a Regulator, stated in part, years after Bonney's death; "I never enjoyed better company. He was humorous and told me many amusing stories. He always found a touch of humor in everything, being naturally full of fun and jollity. Though he was serious in emergencies, his humor was often apparent even in such situations. Billy stood with us to the end, brave and reliable, one of the best soldiers we had. He never pushed in his advice or opinions, but he had a wonderful presence of mind. The tighter the place the more he showed his cool nerve and quick brain. He never seemed to care for money, except to buy cartridges with. Cartridges were scarce, and he always used about ten times as many as everyone else. He would practice shooting at anything he saw, from every conceivable angle, on and off his horse".[29]

- George Coe, cousin to Frank and also a Regulator, stated in part; "Billy was a brave, resourceful and honest boy. He would have been a successful man under other circumstances. The Kid was a thousand times better and braver than any man hunting him, including Pat Garrett".[29]

- Susan McSween, widow of Alexander McSween, stated in part; "Billy was not a bad man, that is he was not a murderer who killed wantonly. Most of those he killed deserved what they got. Of course I cannot very well defend his stealing horses and cattle, but when you consider that the Murphy Dolan and Riley people forced him into such a lawless life through efforts to secure his arrest and conviction, it is hard to blame the poor boy for what he did".[29]

- Deluvina Maxwell, friend to Billy the Kid, stated; "Garrett was afraid to go back in the room to make sure of whom he had shot. I went in and was the first to discover that they had killed my little boy. I hated those men and am glad that I lived long enough to see them all dead and buried".[29]

- Louis Abraham, a friend to Bonney in Silver City, New Mexico, stated; "The story of Billy the Kid killing a blacksmith in Silver City is false. Billy was never in any trouble at all. He was a good boy, maybe a little too mischievous at times. When the boy was placed in jail and escaped, he was not bad, just scared. If he had only waited until they let him out he would have been all right, but he was scared and ran away. He got in with a band of rustlers in Apache Tejo in part of the county where he was made a hardened character".[29]

Imposters

Legend grew over time that Billy the Kid had somehow cheated death, despite eyewitness accounts. At least two men claimed to be Bonney, and were successful in convincing at least a few people.

Brushy Bill

In 1949, a paralegal named William Morrison located a man in West Texas named Ollie P. Roberts, nicknamed "Brushy Bill", who claimed to be the actual Billy the Kid, and that he indeed had not been shot and killed by Pat Garrett in 1881. Most historians reject the Brushy Bill claim. There were numerous points that both supported and discounted Roberts claim. Although, as stated, most historians discount his claims, people continue to proclaim that he was Billy the Kid. Without DNA evidence, it is likely the battle between Roberts' supporters and his opponents will continue indefinitely.

Despite discrepancies in birth dates and physical appearance, the town of Hico, Texas (Brushy Bill's residence), has capitalized on the Kid's infamy by opening the Billy The Kid Museum.

John Miller

Another claimant to the title of Billy the Kid was John Miller, whose family claimed him posthumously to be Billy the Kid in 1938. Miller was buried at the state-owned Pioneers' Home Cemetery in Prescott, Arizona. Tom Sullivan, former sheriff of Lincoln County, and Steve Sederwall, former mayor of Capitan, disinterred the bones of John Miller in May 2005.[54] DNA samples from the remains were sent to a lab in Dallas, Texas, to be compared against traces of blood taken from a bench that was believed to be the one Bonney's body was placed on after he was shot to death. The pair had been searching for Bonney's physical remains since 2003, beginning in Fort Sumner, New Mexico, and eventually ending up in Arizona. To date, no results of the DNA tests have been made public, although Sederwall has obliquely stated, "What I know is not what's written in history. What I know about this case differs from history".

Popular culture

Billy the Kid has been the subject or inspiration for many popular works, including:

Film

- Billy the Kid, 1930 film directed by King Vidor, starring Johnny Mack Brown as Billy and Wallace Beery as Pat Garrett

- Billy the Kid Returns, 1938: Roy Rogers plays a dual role, Billy the Kid and his dead-ringer lookalike who shows up after the Kid has been shot by Pat Garrett.

- Billy the Kid, 1941 remake of the 1930 film, starring Robert Taylor and Brian Donlevy

- The Outlaw, Howard Hughes' 1943 motion picture

- The Kid from Texas (1950, Universal International) film starring Audie Murphy--location of title character's place of origin changed to appeal to Texans and capitalize on Murphy association with that state

- The Left Handed Gun, Arthur Penn's 1958 motion picture starring Paul Newman

- The Tall Man, 1960 TV series featuring Barry Sullivan as Pat Garrett, the "Tall Man", and Clu Gulager as Billy.

- Billy the Kid vs Dracula, William Beaudine's 1966 motion picture with John Carradine

- Chisum, 1970 movie starring John Wayne as John Chisum, dealing with Billy the Kid's involvement in the Lincoln County War, portrayed by Geoffrey Deuel

- Su Precio...Unos Dólares,[55] a 1970 Mexican film with the characters William Bonney and 'Calamity Jane' Canary.

- Dirty Little Billy,[56] Stan Dragoti's 1972 film starring Michael J. Pollard.

- Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Sam Peckinpah's 1973 motion picture with Kris Kristofferson as Billy, James Coburn as Pat Garrett and with a soundtrack by Bob Dylan

- Gore Vidal's Billy the Kid,[57] Gore Vidal's 1989 film starring Val Kilmer as Billy and Duncan Regehr as Pat Garrett

- Young Guns, Christopher Cain's 1988 motion picture starring Emilio Estevez as Billy and Patrick Wayne, son of John Wayne as Pat Garrett

- Bill And Ted's Excellent Adventure, 1989 film starring Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter, with Dan Shor as Billy the Kid

- Young Guns II, Geoff Murphy's 1990 motion picture starring Emilio Estevez as Billy and William Petersen as Pat Garrett

- Requiem for Billy the Kid, Anne Feinsilber's 2006 motion picture starring Kris Kristofferson

- I'm Not There, (2007) uses Billy the Kid as a persona for Bob Dylan

- In BloodRayne II: Deliverance Billy The Kid is depicted as a Vampire outlaw with a Slavic accent. And is defeated jointly by Rayne and Patt Garrett

Games

- Billy the Kid Returns, a PC game based on the life of Billy the Kid published by Alive Software in 1993

- The Legend of Billy the Kid, a game published by Ocean Software in 1991 for PC and Amiga.

Music

- Bob Dylan's album Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, soundtrack of the 1973 film by Sam Peckinpah

- Jon Bon Jovi's album "Blaze of Glory", used as part of the soundtrack for Young Guns II, and featured the song "Billy Get Your Gun".

- Running Wild's song, "Billy the Kid"

- Charlie Daniels's song, "Billy the Kid"

- Billy Dean's song, "Billy the Kid"

- Diablo Royale's song, "Dead at 21"

- "Me and Billy The Kid", written and recorded by Joe Ely. Also recorded by Marty Stuart and Pat Green.

- Ricky Fitzpatrick's song, "Ballad of Billy the Kid",

- Jerry Granelli's album from 2005 "Sand Hills Reunion" featuring words and music about Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett.

- Billy Joel's song, "The Ballad of Billy the Kid"

- Chris LeDoux's song, "Billy the Kid"

- Will Oldham has related his moniker "Bonnie Prince Billy" to Billy the Kid's alias "William Bonney"

- Tom Pacheco's song "Nobody ever killed Billy the Kid" on his disc "Woodstock Winter"

- Tom Petty's song, "Billy the Kid"

- Marty Robbins' song "Billy the Kid" from the album Gunfighter Ballads & Trail Songs Volume 3

- German Heavy Metal veterans Running Wild's song, "Billy the Kid"

- Dave Stamey's "The Skies of Lincoln County", which features the deceased Bonney as narrator, answering historical distortions by Pat Garrett

- Two Gallants' song "Las Cruces Jail"

- Rapper Fabolous has the alter-ego William H. Bonney for his love of being a babyface outlaw who has his way with women

- Why? references Billy the Kid in "Song of the Sad Assassin"

Stage

- Aaron Copland's 1938 ballet, Billy the Kid

- Joseph Santley's 1906 Broadway play co-written by Santley, in which he also starred

Television and radio

- Purgatory, a 1999 made-for-TV movie on TNT, played by Donnie Wahlberg

- Billy the Kid, a New Mexico PBS documentary

- The first episode of the radio program Gunsmoke, titled Billy the Kid, in which Billy is a 12 year old boy from Kansas who kills a rancher with a knife in the back to steal his pistol, and escapes on a stolen horse.

- The 2003 Discovery Channel Quest, "Billy the Kid: Unmasked" investigated the life and death of Billy the Kid through forensic science.

- The Histeria! episode "The Wild West" featured Billy the Kid as the guest host, portraying him as an actual kid pretending to host a kids' show (ala Howdy Doody) while on the run from the law.

- TV series The Tall Men ran from 1960 to 1962, starring Clu Gulager as Billy and Barry Sullivan as Pat Garrett

- TV series The Simpsons featured an episode (Treehouse of Horror XIII) where William H. Bonney (Billy the Kid) comes back to life and takes control of Springfield.

- TV series The Time Tunnel eponymous episode Billy the Kid: time travellers encounter Billy, portrayed by Robert Walker, Jr..

- TV series Voyagers! episode "Bully and Billy": time travellers encounter William H. Bonney (Billy the Kid).

- TV series Maverick featured an episode where Bret (James Garner) meets several infamous outlaws, including Billy the Kid.

Comics

- Belgian comic book series Lucky Luke has Billy the Kid as an antagonist in several of its issues, portraying him as a juvenile (or juvenile-looking) outlaw of small stature and childish behaviour. Billy frequently cries, forces the saloon to serve milk and robs grocery stores for lollipops.

Notes

- ^ "Early Life". aboutbillythekid.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 244.

- ^ a b c d Wallis (2007), p. 129.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 222–223.

- ^ Rausch (1995), p. 126.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 244–245.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 249–250.

- ^ a b c d Wallis (2007), p. 6.

- ^ "The Ancestors of Mit Romney". wargs.com. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 153–156.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 14.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 16.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 52–56.

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), p. 78.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 64.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 76.

- ^ Wallis (2007), 84–85.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 83.

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), p. 87.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 87–88.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 89.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 95.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 103.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 107.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 110–111.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 114.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e f "Eulogy". aboutbillythekid.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04. Cite error: The named reference "eulogy" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Wallis (s007), p. 116.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 119.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 128.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 123–131.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 142.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 143–144.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 144.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 159.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 193–196.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 196–197.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 197–198.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 198–199.

- ^ a b c d "Chronology of Billy the Kid". Shadows of the Past, Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Sheriff William Brady". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff George Hindman". The Officers Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff James Carlysle". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff James W. Bell". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Deputy Marshal Robert Olinger". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ O'Toole, Deborah. "Billy the Kid: Myths and Truths". tripod.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Tourist Attractions". Fort Sumner Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ a b "Chronology of the Life of Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War, Part 2". angelfire.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Fact v. Myth". aboutbillythekid.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Brushy Bill–The Truth?". nmia.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Wild West: Billy the Kid". tripod.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ Banks, Leo W. "A New Billy the Kid?". Tucson Weekly. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Su Precio...Unos Dólares". Imdb.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Dirty Little Billy". imdb.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Billy the Kid". imdb.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

References

- Burns, Walter Noble (2001). The Saga of Billy the Kid. Old Saybrook, CN: Konecky & Konecky Associates. ISBN 1568521782

- Jacobsen, Joel (1997). Such Men as Billy the Kid: The Lincoln County War Reconsidered. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803276060

- Rasch, Philip J. (1995). Trailing Billy the Kid. Stillwater, OK: Western Publications. ISBN 0935269193

- Trachman, Paul (1974). The Old West: The Gunfighters. New York: Time-Life Books.

- Tuska, John (1983). Billy the Kid, A Handbook. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803294069

- Utley, Robert M. (1989). Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Wallis, Michael (2007). Billy the Kid: The Endless Ride. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393060683

- DesertUSA: "The Desert's Baddest Boy"

- The Last Escape of Billy the Kid

External links

- Findagrave: Billy the Kid

- Billy the Kid Outlaw Gang

- About Billy the Kid

- Billy the Kid: Outlaw Legend

- Billy the Kid and Posse?

- Court TV's Crime Library: Billy the Kid

- Billy the Kid fanlisting

- Wild West magazine, Billy the Kid: The Great Escape, Barbara Tucker Peterson and Louis Hart, August 1998

- Wild West magazine, The Hunting of Billy the Kid, Frederick Nolan, June 2003

- Wild West magazine, Billy the Kid and the U.S. Marshals Service, David S. Turk, February 2007 (issued December 2006)

- Billy the Kid National Scenic Byway

- Statements made about Billy the Kid by those who knew him, after his death

- 1859 births

- 1881 deaths

- American Presbyterians

- Americans convicted of murder

- Deaths by firearm in the United States

- Outlaws of the American Old West

- Irish-Americans

- People from New Mexico

- People from Manhattan

- People from New York City

- Gunmen of the American Old West

- People convicted of murdering police officers

- American folklore