Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Difference between revisions

m →Life: wikilinks, spelling, style |

m grammar |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|European composer (1756–1791)}} |

|||

{{redirect|Mozart}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Mozart}} |

|||

{{pp|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Use British English|date=September 2020}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2023}} |

|||

{{Infobox classical composer |

|||

| name = Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart |

|||

| image = Mozart Portrait Croce.jpg |

|||

| caption = Portrait, {{circa|1781}} |

|||

| parents = [[Leopold Mozart]]<br />[[Anna Maria Mozart]] |

|||

| birth_place = [[Mozart's birthplace|Getreidegasse 9]], Salzburg |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|1791|12|5|1756|1|27|df=y}} |

|||

| death_place = [[Vienna]] |

|||

| death_cause = <!--[[Death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Disputed]]--> |

|||

| list_of_works = [[List of compositions by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|List of compositions]] |

|||

| signature = Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Signature.svg |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1756|1|27|df=y}} |

|||

| birth_name = <!--Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart ([[Mozart's name|other names]]) --> |

|||

| notable_family= [[Mozart family]] |

|||

| spouse = [[Constanze Mozart]] |

|||

| children = <!--6, two survived infancy: {{Unbulleted list|[[Karl Thomas Mozart]]|[[Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart]]}}--> |

|||

}} |

|||

<!-- |

|||

There is consensus IN FAVOR of having an infobox in this article (see [[Special:PermanentLink/1147340491#c-Maddy_from_Celeste-20230330092400-Mozart_Infobox_RFC]] from March 2023). Changes to the infobox should be discussed on the article talk page first to avoid edit warring or disruption. |

|||

Please do not edit this lead section without discussing first on talk page—it's the result of a consensus that involved some work to reach. |

|||

[[Image:Edliner_Mozart.jpg|W. A. Mozart, 1790 portrait by Johann Georg Edlinger|thumb|right|250px]] |

|||

--> |

|||

'''Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart'''{{efn|1=Sources vary regarding the English pronunciation of Mozart's name. {{harvnb|Fradkin|1996}}, a guide for classical music radio, strongly recommends the use of the phoneme {{IPA|[ts]}} for the letter ''z'' (thus {{IPAc-en|ˈ|w|ʊ|l|f|ɡ|æ|ŋ|_|ˌ|æ|m|ə|ˈ|d|eɪ|ə|s|_|ˈ|m|oʊ|t|s|ɑːr|t}} {{respell|WUULF|gang|_|AM|ə|DAY|əs|_|MOHT|sart}}), but otherwise considers English-like pronunciation fully acceptable. The German pronunciation is {{IPA-de|ˈvɔlfɡaŋ ʔamaˈdeːʊs ˈmoːtsaʁt||De-Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.ogg}}.}}{{efn|1=Baptised as '''Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart'''. Mozart used, at different times and places, different versions of his own name; for details, see [[Mozart's name]].}} (27 January 1756{{snd}}5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential [[composer]] of the [[Classical period (music)|Classical period]]. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition resulted in [[List of compositions by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|more than 800 works]] representing virtually every Western classical genre of his time. Many of these compositions are acknowledged as pinnacles of the [[symphony|symphonic]], [[concerto|concertante]], [[chamber music|chamber]], operatic, and [[choir|choral]] repertoire. Mozart is widely regarded as being one of the greatest composers in the history of Western music,{{sfn|Buch|2017|loc="Introduction"}} with his music admired for its "melodic beauty, its formal elegance and its richness of harmony and texture".{{sfn|Eisen|Sadie|2001}} |

|||

Born in [[Prince-Archbishopric of Salzburg|Salzburg]], then in the [[Holy Roman Empire]] and currently in [[Austria]], Mozart showed [[Child prodigy|prodigious]] ability from his earliest childhood. At age five he was already competent on keyboard and violin, he had begun to compose, and he performed before European royalty. His father took him on a [[Mozart family grand tour|grand tour]] of Europe and then [[Mozart in Italy|three trips to Italy]]. At 17, he was a musician at the Salzburg court but grew restless and travelled in search of a better position. |

|||

'''Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart''' ([[January 27]], [[1756]] – [[December 5]], [[1791]]) is among the most significant and enduringly popular [[composer]]s of [[European classical music]]. His enormous output includes works that are widely acknowledged as pinnacles of [[symphony|symphonic]], [[chamber music|chamber]], [[piano]], [[opera|operatic]], and [[choir|choral]] music. Many of his works are part of the standard concert repertory and are widely recognized as masterpieces of the classical style. Mozart himself is universally and nationally recognized as a musical [[genius]], having learned to compose at the age of five and showing an encyclopedic and prodigious grasp of almost every musical form of his time despite having lived only for 35 years. |

|||

While visiting Vienna in 1781, Mozart was dismissed from his Salzburg position. He stayed in Vienna, where he achieved fame but little financial security. During his final years there, he composed many of his best-known [[List of symphonies by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|symphonies]], [[List of compositions by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart#Concertos|concertos]], and [[List of operas by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|operas]]. His [[Requiem (Mozart)|Requiem]] was largely unfinished at the time of [[Death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|his death]] at age 35, the circumstances of which are uncertain and much mythologised. |

|||

==Life== |

|||

== |

==Life and career== |

||

[[File:Casa natale di Mozart.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|Mozart's birthplace at Getreidegasse 9, Salzburg]] |

|||

===Early life=== |

|||

Mozart was born in [[Salzburg]] on [[January 27]], [[1756]]. His parents were [[Leopold Mozart]] and Anna Maria Pertl Mozart. His official name was Johannes Chrystomus Wolfgang Theohilus Mozart, but after some rearranging and translations became Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart was baptized the next day at St. Rupert's Cathedral. As a young child he grew up with a musically enriched father, Leopold, who was one of Europe's leading musical pedagogues, having written ''Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule'' only a few months after Mozart's birth. By age three Mozart's musical abilities were known to his family. His father gave him intensive training in the piano and violin. Mozart was a fast learner, and began composing by age six. |

|||

====Family and childhood==== |

|||

{{see also|Mozart's name|Mozart family|Mozart's nationality}} |

|||

===The years of travel=== |

|||

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born on 27 January 1756 to [[Leopold Mozart]] (1719–1787) and [[Anna Maria Mozart|Anna Maria]], née Pertl (1720–1778), at [[Mozart's birthplace|Getreidegasse 9]] in Salzburg.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Austria|first1=Rosemarie|last1=Arnold|first2=Robert|last2=Taylor|first3=Rainer|last3=Eisenschmid|year=2009|publisher=Baedeker|isbn=978-3-8297-6613-5|oclc=416424772}}</ref> Salzburg was the capital of the [[Archbishopric of Salzburg]], an ecclesiastic principality in the [[Holy Roman Empire]] (today in [[Austria]]).{{efn|1=Source: {{harvnb|Wilson|1999|p=2}}. The many changes of European political borders since Mozart's time make it difficult to assign him an unambiguous nationality; for discussion, see [[Mozart's nationality]].}} He was the youngest of seven children, five of whom died in infancy. His elder sister was [[Maria Anna Mozart]] (1751–1829), nicknamed "Nannerl". Mozart was baptised the day after his birth, at [[Salzburg Cathedral|St. Rupert's Cathedral]] in Salzburg. The baptismal record gives his name in Latinized form, as ''Joannes<!--This is not a spelling mistake; it is indeed "Joannes"--> Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart''. He generally called himself "Wolfgang Amadè Mozart"<!--Caution to outraged Francophones: this is of course not "correct" orthography in either (modern) French or even Italian. The point here is that it is the way Mozart (wrongly?) spelled it, according to the source.-->{{sfn|Deutsch|1965|p=9}} as an adult, but [[Mozart's name|his name]] had many variants. |

|||

[[Image:Martini bologna mozart 1777.jpg|thumb|"Bologna Mozart"—Mozart aged 21 in 1777]] |

|||

Leopold Mozart, a native of [[Augsburg]],{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=21}} then an Imperial Free City in the Holy Roman Empire, was a minor composer and an experienced teacher. In 1743, he was appointed as the fourth violinist in the musical establishment of Count [[Leopold Anton von Firmian]], the ruling [[Archbishopric of Salzburg#Prince-Bishopric (1213–1803)|Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg]].{{sfn|Eisen|Sadie|2001}} Four years later, he married Anna Maria in Salzburg. Leopold became the orchestra's deputy [[Kapellmeister]] in 1763. During the year of his son's birth, Leopold published a violin textbook, ''[[Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule]]'', which achieved success.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=32}} |

|||

Leopold realized that he could earn a substantial income by showcasing his son as a ''[[Wunderkind]]'' in the courts of Europe. Mozart soon gained fame as a musical prodigy capable of such feats as playing blindfolded <!-- the following statement requires supporting evidence or source: or with his hands behind his back, -->or improvising competently and at length on difficult passages he had never seen before. His older sister [[Maria Anna "Nannerl" Mozart|Maria Anna]], nicknamed "Nannerl", was a talented pianist and accompanied her brother on the earlier tours. Mozart wrote a number of piano pieces, in particular [[Duet (music)|duet]]s and [[duo]]s, to play with her. On one occasion when Mozart became ill, Leopold expressed more concern over the loss of income than over his son's well-being. Constant travel and cold weather may have contributed to his subsequent illness later in life. |

|||

When Nannerl was seven, she began keyboard lessons with her father, while her three-year-old brother looked on. Years later, after her brother's death, she reminisced: |

|||

During his formative years, Mozart completed several journeys throughout [[Europe]], beginning with an exhibition in 1762 at the Court of the Elector of [[Bavaria]] in [[Munich]], then in the same year at the Imperial Court in [[Vienna]]. A long concert tour soon followed (three and a half years), which took him with his father to the courts of [[Munich]], [[Mannheim]], [[Paris]], [[London]], [[The Hague]], again to [[Paris]], and back home via [[Zürich]], [[Donaueschingen]], and [[Munich]]. They went to Vienna again in late [[1767]] and remained there until December [[1768]]. |

|||

<blockquote>He often spent much time at the [[Keyboard instrument|clavier]], picking out thirds, which he was ever striking, and his pleasure showed that it sounded good.{{nbsp}}... In the fourth year of his age his father, for a game as it were, began to teach him a few minuets and pieces at the clavier.{{nbsp}}... He could play it faultlessly and with the greatest delicacy, and keeping exactly in time.{{nbsp}}... At the age of five, he was already composing little pieces, which he played to his father who wrote them down.{{sfn|Deutsch|1965|p=455}}</blockquote> |

|||

[[File:Louis Carrogis dit Carmontelle - Portrait de Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Salzbourg, 1756-Vienne, 1791) jouant à Paris avec son père Jean... - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|right|upright|Mozart family on tour: Leopold, Wolfgang, Nannerl; watercolour by [[Louis Carrogis Carmontelle|Carmontelle]], {{circa|1763}}{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=44}}]] |

|||

[[image:mozart.birth.500pix.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Mozart's birthplace at 9 Getreidegasse, Salzburg, Austria]] |

|||

These early pieces, [[Köchel catalogue|K.]] 1–5, were recorded in the ''[[Nannerl Notenbuch]]''. There is some scholarly debate about whether Mozart was four or five years old when he created his first musical compositions, though there is little doubt that Mozart composed his first three pieces of music within a few weeks of each other: K. 1a, 1b, and 1c.<ref>{{IMSLP |

|||

|work=Andante in C major, K.1a (Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus)|cname=Andante in C major, K. 1a |

|||

|work2=Allegro in C major, K.1b (Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus)|cname2=Allegro in C major, K. 1b |

|||

|work3=Allegro in F major, K.1c (Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus)|cname3=Allegro in F major, K.1c}}</ref> |

|||

In his early years, Wolfgang's father was his only teacher. Along with music, he taught his children languages and academic subjects.<ref name="solomon 1995 39" /> Biographer [[Maynard Solomon|Solomon]] notes that, while Leopold was a devoted teacher to his children, there is evidence that Mozart was keen to progress beyond what he was taught.<ref name="solomon 1995 39">{{harvnb|Solomon|1995|pp=39–40}}</ref> His first ink-spattered composition and his precocious efforts with the violin were of his initiative and came as a surprise to Leopold,{{sfn|Deutsch|1965|p=453}} who eventually gave up composing when his son's musical talents became evident.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=33}} |

|||

After one year spent in Salzburg, three trips to [[Italy]] followed: from December 1769 to March 1771, from August to December 1771, and from October 1772 to March 1773. During the first of these trips, Mozart met [[Andrea Luchesi]] in [[Venice]], [[Giovanni Battista Martini|G.B. Martini]] in [[Bologna]], and was accepted as a member of the famous ''[[Accademia Filarmonica]]''. A highlight of the Italian journey, which is now an almost legendary tale, occurred when he heard [[Gregorio Allegri]]'s ''[[Miserere (Allegri)|Miserere]]'' once in performance in the [[Sistine Chapel]], then wrote it out in its entirety from memory, only returning a second time to correct minor errors: he thus produced the first illegal copy of this closely-guarded property of the Vatican <small><nowiki>[</nowiki>[http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Documents_describing_Mozart%27s_transcription_of_the_Allegri_Miserere source documents]<nowiki>]</nowiki></small>. |

|||

====1762–73: Travel==== |

|||

In September of 1777, accompanied only by his mother, Mozart began a tour of [[Europe]] that included [[Munich]], [[Mannheim]], and [[Paris]], where his mother died. |

|||

{{Main| Mozart family grand tour|Mozart in Italy}} |

|||

While Wolfgang was young, his family made several European journeys in which he and Nannerl performed as [[Child prodigy|child prodigies]]. These began with an exhibition in 1762 at the court of [[Prince-elector]] [[Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria|Maximilian III]] of Bavaria in Munich, and at the Imperial Courts in Vienna and Prague. A long concert tour followed, spanning three and a half years, taking the family to the courts of Munich, [[Mannheim]], Paris, London,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart {{!}} Composer {{!}} Blue Plaques|url=https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/wolfgang-amadeus-mozart/|access-date=25 September 2020|website=English Heritage|archive-date=12 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210412010318/https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/wolfgang-amadeus-mozart/|url-status=live}}</ref> Dover, The Hague, Amsterdam, Utrecht, [[Mechelen]] and again to Paris, and back home via [[Zürich]], [[Donaueschingen]], and Munich.{{sfn|Grove|1954|page=926}} During this trip, Wolfgang met many musicians and acquainted himself with the works of other composers. A particularly significant influence was [[Johann Christian Bach]], whom he visited in London in 1764 and 1765. When he was eight years old, Mozart wrote [[Symphony No. 1 (Mozart)|his first symphony]], most of which was probably transcribed by his father.<ref>{{cite web|title=Mozart Biography|website=midiworld.com|url=http://midiworld.com/mozart1.htm|access-date=20 December 2014|date=2009|first=Joe|last=Meerdter|archive-date=1 July 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170701195157/http://midiworld.com/mozart1.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

During his trips, Mozart met a great number of musicians and acquainted himself with the works of other great composers. A particularly important influence was [[Johann Christian Bach]], who befriended Mozart as a child in London in 1764–65. JC Bach's work is often taken to be an inspiration for the distinctive surface texture of Mozart's music, though not its architecture or drama. |

|||

[[File:Portrait of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at the age of 13 in Verona, 1770.jpg|thumb|left|Mozart aged 14 in January 1770 (School of Verona, attributed to [[Giambettino Cignaroli]])]] |

|||

Even non-musicians caught Mozart's attention: he was so taken by the sound created by [[Benjamin Franklin]]'s [[glass harmonica]] that he composed several pieces of music for it. |

|||

{{listen|type=music|image=none|help=no |

|||

===Mozart in Vienna=== |

|||

| filename = Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Quaerite primum regnum Dei à4, K.86 73v (1770).ogg |

|||

| title = Antiphon "Quaerite primum regnum Dei", K. 86/73v |

|||

| description = Composed 9 October 1770 for admission to the [[Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna]]; Performed by Phillip W. Serna, treble, tenor & bass [[viol]]s |

|||

}} |

|||

The family trips were often challenging, and travel conditions were primitive.{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|pp=51, 53}} They had to wait for invitations and reimbursement from the nobility, and they endured long, near-fatal illnesses far from home: first Leopold (London, summer 1764),{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|pp=82–83}} then both children (The Hague, autumn 1765).{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|pp=99–102}} The family again went to Vienna in late 1767 and remained there until December 1768. |

|||

After one year in Salzburg, Leopold and Wolfgang set off for Italy, leaving Anna Maria and Nannerl at home. This tour lasted from December 1769 to March 1771. As with earlier journeys, Leopold wanted to display his son's abilities as a performer and a rapidly maturing composer. Wolfgang met [[Josef Mysliveček]] and [[Giovanni Battista Martini]] in [[Bologna]] and was accepted as a member of the famous [[Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna|Accademia Filarmonica]]. There exists a myth, according to which, while in Rome, he heard [[Gregorio Allegri]]'s ''[[Miserere (Allegri)|Miserere]]'' twice in performance in the [[Sistine Chapel]]. Allegedly, he subsequently wrote it out from memory, thus producing the "first unauthorized copy of this closely guarded property of the [[Holy See|Vatican]]". However, both origin and plausibility of this account are disputed.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Allegri's Miserere: Conclusions |url=https://www.ancientgroove.co.uk/essays/theories.html |access-date=11 November 2022 |website=www.ancientgroove.co.uk |archive-date=9 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221109040924/https://www.ancientgroove.co.uk/essays/theories.html |url-status=live }}</ref>{{sfn|Gutman|2000|p=271}}{{efn|1=For further details of the story, see {{section link|Miserere (Allegri)|History}}.}}<ref>{{cite news|author= Chrissochoidis, Ilias|title=London Mozartiana: Wolfgang's disputed age & early performances of Allegri's ''Miserere''|newspaper=[[The Musical Times]]| volume= 151|number= 1911 |date=Summer 2010|pages= 83–89}} Provides new information on this episode.</ref> |

|||

In 1781 Mozart visited [[Vienna]] in the company of his employer, the harsh [[Hieronymus Colloredo|Prince-Archbishop Colloredo]], and fell out with him. According to Mozart's own testimony, he was dismissed literally "with a kick in the seat of the pants." Mozart chose to settle and develop his career in Vienna after its aristocracy began to take an interest in him. |

|||

In Milan, Mozart wrote the opera ''[[Mitridate, re di Ponto]]'' (1770), which was performed with success. This led to further opera [[commission (art)|commissions]]. He returned with his father twice to Milan (August–December 1771; October 1772{{snd}}March 1773) for the composition and premieres of ''[[Ascanio in Alba]]'' (1771) and ''[[Lucio Silla]]'' (1772). Leopold hoped these visits would result in a professional appointment for his son, and indeed ruling [[Ferdinand Karl, Archduke of Austria-Este|Archduke Ferdinand]] contemplated hiring Mozart, but owing to his mother [[Maria Theresa|Empress Maria Theresa]]'s reluctance to employ "useless people", the matter was dropped{{efn|1={{harvnb|Eisen|Keefe|2006|p=268}}: "You ask me to take the young Salzburger into your service. I do not know why not believing that you have need for a composer or of useless people.{{nbsp}}... What I say is intended only to prevent you from burdening yourself with useless people and giving titles to people of that sort. In addition, if they are at your service, it degrades that service when these people go about the world like beggars."}} and Leopold's hopes were never realized.{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|pp=172, 183–185}} Toward the end of the journey, Mozart wrote the solo [[motet]] ''[[Exsultate, jubilate]]'', [[Köchel catalogue|K.]]165. |

|||

On [[August 4]], [[1782]], he married [[Constanze Weber]] (also spelled "Costanze") against his father's wishes. He and Constanze had six children, of whom only two survived infancy. Neither of these two, Karl Thomas (1784–1858) or [[Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart|Franz Xaver Wolfgang]] (later a minor composer himself; 1791–1844), married or had children. |

|||

===1773–77: Employment at the Salzburg court=== |

|||

1782 was an auspicious year for Mozart's career; his opera ''[[Die Entführung aus dem Serail]]'' ("The Abduction from the Seraglio") was a great success, and he began a series of concerts at which he premiered his own [[piano concerto]]s as [[conducting|conductor]] and [[soloist]]. |

|||

[[File:Mozart's old home.jpg|thumb|upright|{{interlanguage link|Tanzmeisterhaus|de}}, Salzburg, Mozart family residence from 1773; reconstructed 1996]] |

|||

[[Image:5000ATS.jpg|right|thumb|The first foil application (kinegram®) banknote, the 1988 [[Austria]]n 5000 Schilling note. Last 5000 [[Schilling]] banknote before [[Euro]].]] [[Image:1e_oes.png|right|thumb| [[Austria]]n 1 [[Euro]] coin]]In 1782–83, Mozart became closely acquainted with the work of [[Johann Sebastian Bach|JS Bach]] and [[Georg Frideric Handel|Handel]], as a result of the influence of Baron [[Gottfried van Swieten]], who owned many manuscripts of works by the Baroque masters. Mozart's study of these works led, first, to a number of works of his own imitating Baroque style, and later had a powerful influence on his personal musical style, as seen for instance in the [[fugue|fugal]] passages in ''[[Die Zauberflöte]]'' ("The Magic Flute") and the [[Symphony No. 41 (Mozart)|41st Symphony]]. |

|||

After finally returning with his father from Italy on 13 March 1773, Mozart was employed as a court musician by the ruler of Salzburg, [[Hieronymus von Colloredo (1732–1812)|Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo]]. The composer had many friends and admirers in Salzburg{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=106}} and had the opportunity to work in many genres, including symphonies, sonatas, string quartets, [[Mass (music)|masses]], serenades, and a few minor operas. Between April and December 1775, Mozart developed an enthusiasm for violin concertos, producing a series of five (the only ones he ever wrote), which steadily increased in their musical sophistication. The last three—[[Violin Concerto No. 3 (Mozart)|K. 216]], [[Violin Concerto No. 4 (Mozart)|K. 218]], [[Violin Concerto No. 5 (Mozart)|K. 219]]—are now staples of the repertoire. In 1776, he turned his efforts to [[Mozart piano concertos|piano concertos]], culminating in the E{{music|flat}} concerto [[Piano Concerto No. 9 (Mozart)|K. 271]] of early 1777, considered by critics to be a breakthrough work.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=103}} |

|||

In his early Vienna years, Mozart met [[Joseph Haydn]], and the two composers became friends. When Haydn visited Vienna, they sometimes played in an impromptu [[string quartet]] together. Mozart's six quartets dedicated to Haydn date from 1782–85, and are often judged to be his response to Haydn's Opus 33 set from 1781. Haydn was soon in awe of Mozart, and when he first heard the last three of Mozart's series, he told [[Leopold Mozart|Leopold]], "Before God and as an honest man I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name. He has taste, and what is more, the most profound knowledge of composition." |

|||

Despite these artistic successes, Mozart grew increasingly discontented with Salzburg and redoubled his efforts to find a position elsewhere. One reason was his low salary, 150 florins a year;{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=98}} Mozart longed to compose operas, and Salzburg provided only rare occasions for these. The situation worsened in 1775 when the court theatre was closed, especially since the other theatre in Salzburg was primarily reserved for visiting troupes.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=107}} |

|||

As an adult, Mozart, influenced by the ideas of the eighteenth century [[The Age of Enlightenment|European Enlightenment]], became a [[Freemason]], although his lodge was a specifically Catholic rather than deistic one, and worked fervently and successfully to convert his father before the latter's death in 1787. His last opera, ''Die Zauberflöte'', includes Masonic themes and allegory. He was in the same [[Masonic Lodge]] as Haydn. |

|||

Two long expeditions in search of work interrupted this long Salzburg stay. Mozart and his father visited Vienna from 14 July to 26 September 1773, and Munich from 6{{nbsp}}December 1774 to March 1775. Neither visit was successful, though the Munich journey resulted in a popular success with the premiere of Mozart's opera ''[[La finta giardiniera]]''.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=109}} |

|||

Mozart's life was fraught with financial difficulty and illness. Often, he received no payment for his work, and what sums he did receive were quickly consumed by his extravagant lifestyle. |

|||

===1777–78: Journey to Paris=== |

|||

Mozart spent the year 1786 in [[Vienna]] in an apartment which may be visited today at Domgasse 5 behind St Stephen's Cathedral; it was here that Mozart composed ''[[Le nozze di Figaro]]''. He then followed this up in 1787 with one of his greatest works, ''[[Don Giovanni]]''. |

|||

[[File:Martini bologna mozart 1777.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|left|Mozart wearing the badge of the [[Order of the Golden Spur]] which he received in 1770 from [[Pope Clement XIV]] in Rome. The painting is a 1777 copy of a work now lost.{{sfn|Vatican|1770}}]] |

|||

In August 1777, Mozart resigned his position at Salzburg{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|p=225}}{{efn|1=Archbishop Colloredo responded to the request by dismissing both Mozart and his father, though the dismissal of the latter was not actually carried out.}} and on 23 September ventured out once more in search of employment, with visits to [[Augsburg]], Mannheim, Paris, and Munich.{{sfn|Sadie|1998}} |

|||

===Mozart and Prague=== |

|||

Mozart became acquainted with members of the [[Mannheim school|famous orchestra]] in Mannheim, the best in Europe at the time. He also fell in love with [[Aloysia Weber]], one of four daughters of a musical family. There were prospects of employment in Mannheim, but they came to nothing,<ref>{{cite web|last=Drebes|first=Gerald|title=Die 'Mannheimer Schule'—ein Zentrum der vorklassischen Musik und Mozart|language=de|date=1992|url=http://www.gerald-drebes.ch/page8.html|url-status=dead|website=gerald-drebes.ch|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150207142809/http://www.gerald-drebes.ch/page8.html|archive-date=7 February 2015}}</ref> and Mozart left for Paris on 14 March 1778{{sfn|Deutsch|1965|p=174}} to continue his search. One of his letters from Paris hints at a possible post as an organist at [[Palace of Versailles|Versailles]], but Mozart was not interested in such an appointment.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=149}} He fell into debt and took to pawning valuables.{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|pp=304–305}} The nadir of the visit occurred when Mozart's mother was taken ill and died on 3{{nbsp}}July 1778.{{sfn|Abert|2007|p=509}} There had been delays in calling a doctor—probably, according to Halliwell, because of a lack of funds.{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|p=305}} Mozart stayed with [[Melchior Grimm]] at [[Louise d'Épinay|Marquise d'Épinay]]'s residence, 5 [[rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin]].<ref>[https://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/briefe/letter.php?mid=1026 "Letter by W. A. Mozart to his father"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230122140125/https://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/briefe/letter.php?mid=1026 |date=22 January 2023 }}, Paris, 9 July 1778 (in German); [https://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/objs/raradocs/transcr/pdf_eng/0462_WAM_LM_1778.pdf in English] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230122140138/https://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/objs/raradocs/transcr/pdf_eng/0462_WAM_LM_1778.pdf |date=22 January 2023 }}; [[Mozarteum]]</ref> |

|||

Mozart had a special relationship with [[Prague]] and the people of Prague. The audience here celebrated their [[Figaro]] with the much deserved reverence he was missing in his hometown Vienna. His quote "My Czechs understand me" became very famous in the [[Czech Republic|Czech lands]]. Many tourists follow the tracks of this great composer in Prague and visit the Mozart Museum of the Villa Bertramka where they have the opportunity to enjoy a chamber concert. In Prague, ''[[Don Giovanni]]'' was premiered on October 29, 1787 at the National Theater. In the later years of his life Prague provided Mozart many financial resources from commissions. |

|||

While Mozart was in Paris, his father was pursuing opportunities of employment for him in Salzburg.{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|loc=chs. 18–19}} With the support of the local nobility, Mozart was offered a post as court organist and concertmaster. The annual salary was 450 florins,{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=157}} but he was reluctant to accept.{{sfn|Halliwell|1998|p=322}} By that time, relations between Grimm and Mozart had cooled, and Mozart moved out. After leaving Paris in September 1778 for Strasbourg, he lingered in Mannheim and Munich, still hoping to obtain an appointment outside Salzburg. In Munich, he again encountered Aloysia, now a very successful singer, but she was no longer interested in him.{{sfn|Sadie|1998|loc=§3}} Mozart finally returned to Salzburg on 15 January 1779 and took up his new appointment, but his discontent with Salzburg remained undiminished.<ref>{{cite book|title=Histoire de la musique occidentale|editor1=[[Jean Massin]]|editor2=[[Brigitte Massin]]|publisher=[[Fayard]]|location=Paris|date=1983|page=613|quote=He wrote during that period that, whenever he or someone else played one of his compositions, it was as if the table and chairs were the only listeners.}}</ref> |

|||

===Final illness and death=== |

|||

Mozart's final illness and death are difficult scholarly topics, obscured by Romantic legends and replete with conflicting theories. Scholars disagree about the course of decline in Mozart's health – particularly at what point Mozart became aware of his impending death, and whether this awareness influenced his final works. The Romantic view holds that Mozart declined gradually, and that his outlook and compositions paralleled this decline. In opposition to this, some contemporary scholarship points out correspondence from Mozart's final year indicating that he was in good cheer, as well as evidence that Mozart's death was sudden and a shock to his family and friends. |

|||

Among the better-known works which Mozart wrote on the Paris journey are the [[Piano Sonata No. 8 (Mozart)|A minor piano sonata]], K. 310/300d, the [[Symphony No. 31 (Mozart)|"Paris" Symphony]] (No. 31), which were performed in Paris on 12 and 18 June 1778;{{sfn|Deutsch|1965|p=176}} and the [[Concerto for Flute, Harp, and Orchestra (Mozart)|Concerto for Flute and Harp]] in C major, K. 299/297c.{{sfn|Einstein|1965|pp=276–277}} |

|||

The actual cause of Mozart's death is also a matter of conjecture. His death record listed "hitziges Frieselfieber" ("severe miliary fever"), a description that does not suffice to identify the cause as it would be diagnosed in modern medicine. In fact, dozens of theories have been proposed, which include [[trichinosis]], [[Mercury (element)|mercury]] poisoning, and [[rheumatic fever]]. The contemporary practice of [[bloodletting|bleeding]] medical patients is also cited as a contributing cause. |

|||

===Vienna=== |

|||

Mozart died around 1 am on [[December 5]], [[1791]] while he was working on his final composition, the [[Requiem (Mozart)|Requiem]] (unfinished when he died). A younger composer, [[Franz Xaver Süssmayr]], was engaged by Konstanze to complete the Requiem after Mozart's death. He was not the only composer asked to complete the Requiem but he is associated with it over the others due to his significant contribution. |

|||

====1781: Departure==== |

|||

[[File:Croce MozartFamilyPortrait.jpg|thumb|[[Mozart family]], {{circa|1780}} ([[Johann Nepomuk della Croce|della Croce]]); the portrait on the wall is of Mozart's mother.]] |

|||

In January 1781, Mozart's opera ''[[Idomeneo]]'' premiered with "considerable success" in Munich.{{sfn|Sadie|1980|loc=vol. 12, p. 700}} The following March, Mozart was summoned to Vienna, where his employer, Archbishop Colloredo, was attending the celebrations for the accession of [[Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor|Joseph II]] to the Austrian throne. For Colloredo, this was simply a matter of wanting his musical servant to be at hand (Mozart indeed was required to dine in Colloredo's establishment with the valets and cooks).{{efn|1=Mozart complains of this in a letter to his father, dated 24 March 1781.{{sfn|Spaethling|2000|p=235}}}} He planned a bigger career as he continued in the archbishop's service;{{sfn|Spaethling|2000|p=238}} for example, he wrote to his father: |

|||

According to popular legend, Mozart was penniless and forgotten when he died, and was buried in a pauper's grave. In fact, though he was no longer as fashionable in [[Vienna]] as he had once been, he continued to have a well-paid job at court and receive substantial commissions from more distant parts of Europe, [[Prague]] in particular. Many of his begging letters survive, but they are evidence not so much of poverty as of his habit of spending more than he earned. He was not buried in a "mass grave", but in a regular communal grave according to the 1783 laws. Though the original grave on [[St. Marx cemetery]] was lost, memorial gravestones have been placed there and on [[Zentralfriedhof]]. |

|||

<blockquote>My main goal right now is to meet the emperor in some agreeable fashion, I am absolutely determined he {{em|should get to know me}}. I would be so happy if I could whip through my opera for him and then play a fugue or two, for that's what he likes.<ref name=Spaethling237>{{harvnb|Spaethling|2000|p=237}}; the letter dates from 24 March 1781.</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Mozart did indeed soon meet the Emperor, who eventually was to support his career substantially with commissions and a part-time position. |

|||

In 1809, Constanze married [[Denmark|Danish]] diplomat [[Georg Nikolaus von Nissen]] (1761–1826). Being a fanatical admirer of Mozart, he edited vulgar passages out of many of the composer's letters and wrote a Mozart biography. |

|||

In the same letter to his father just quoted, Mozart outlined his plans to participate as a soloist in the concerts of the ''[[Tonkünstler-Societät]]'', a prominent benefit concert series;<ref name=Spaethling237 /> this plan as well came to pass after the local nobility prevailed on Colloredo to drop his opposition.{{sfn|Spaethling|2000|pp=238–239}} |

|||

Colloredo's wish to prevent Mozart from performing outside his establishment was in other cases carried through, raising the composer's anger; one example was a chance to perform before the Emperor at [[Maria Wilhelmine Thun|Countess Thun]]'s for a fee equal to half of his yearly Salzburg salary. |

|||

The quarrel with the archbishop came to a head in May: Mozart attempted to resign and was refused. The following month, permission was granted, but in a grossly insulting way: the composer was dismissed literally "with a kick in the arse", administered by the archbishop's steward, Count Arco. Mozart decided to settle in Vienna as a freelance performer and composer.<ref name="sadie 1998 4" /> |

|||

The quarrel with Colloredo was more difficult for Mozart because his father sided against him. Hoping fervently that he would obediently follow Colloredo back to Salzburg, Mozart's father exchanged intense letters with his son, urging him to be reconciled with their employer. Mozart passionately defended his intention to pursue an independent career in Vienna. The debate ended when Mozart was dismissed by the archbishop, freeing himself both of his employer and of his father's demands to return. Solomon characterizes Mozart's resignation as a "revolutionary step" that significantly altered the course of his life.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=247}} |

|||

====Early years==== |

|||

{{see also|Haydn and Mozart|Mozart and Freemasonry}} |

|||

Mozart's new career in Vienna began well. He often performed as a pianist, notably in a competition before the Emperor with [[Muzio Clementi]] on 24 December 1781,<ref name="sadie 1998 4">{{harvnb|Sadie|1998|loc=§4}}</ref> and he soon "had established himself as the finest keyboard player in Vienna".<ref name="sadie 1998 4" /> He also prospered as a composer, and in 1782 completed the opera ''[[Die Entführung aus dem Serail]]'' ("The Abduction from the Seraglio"), which premiered on 16 July 1782 and achieved considerable success. The work was soon being performed "throughout German-speaking Europe",<ref name="sadie 1998 4" /> and thoroughly established Mozart's reputation as a composer. |

|||

[[File:Constanze Mozart by Lange 1782.jpg|thumb|upright|1782 portrait of [[Constanze Mozart]] by her brother-in-law [[Joseph Lange]]]] |

|||

Near the height of his quarrels with Colloredo, Mozart moved in with the Weber family, who had moved to Vienna from Mannheim. The family's father, Fridolin, had died, and the Webers were now taking in lodgers to make ends meet.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=253}} |

|||

====Marriage and children==== |

|||

After failing to win the hand of Aloysia Weber, who was now married to the actor and artist [[Joseph Lange]], Mozart's interest shifted to the third daughter of the family, [[Constanze Mozart|Constanze]]. |

|||

The courtship did not go entirely smoothly; surviving correspondence indicates that Mozart and Constanze briefly broke up in April 1782, over an episode involving jealousy (Constanze had permitted another young man to measure her calves in a parlor game).{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=259}} Mozart also faced a very difficult task getting permission for the marriage from his father, [[Leopold Mozart|Leopold]].{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=258}} |

|||

The marriage took place in an atmosphere of crisis. [[Daniel Heartz]] suggests that eventually Constanze moved in with Mozart, which would have placed her in disgrace by the mores of the time.{{sfn|Heartz|2009|p=47}} Mozart wrote to Leopold on 31 July 1782, "All the good and well-intentioned advice you have sent fails to address the case of a man who has already gone so far with a maiden. Further postponement is out of the question."{{sfn|Heartz|2009|p=47}} Heartz relates, "Constanze's sister [[Sophie Weber|Sophie]] had tearfully declared that her mother would send the police after Constanze if she did not return home [presumably from Mozart's apartment]."{{sfn|Heartz|2009|p=47}} On 4 August, Mozart wrote to Baroness von Waldstätten, asking: "Can the police here enter anyone's house in this way? Perhaps it is only a ruse of Madame Weber to get her daughter back. If not, I know no better remedy than to marry Constanze tomorrow morning or if possible today."{{sfn|Heartz|2009|p=47}} |

|||

The couple were finally married on 4{{nbsp}}August 1782 in [[St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna|St. Stephen's Cathedral]], the day before his father's consenting letter arrived in the mail. In the marriage contract, Constanze "assigns to her bridegroom five hundred gulden which ... the latter has promised to augment with one thousand gulden", with the total "to pass to the survivor". Further, all joint acquisitions during the marriage were to remain the common property of both.{{sfn|Deutsch|1965|p=204}} |

|||

The couple had six children, of whom only two survived infancy:{{sfn|Solomon|1995|pp=265–266}} |

|||

* Raimund Leopold (17 June{{snd}}19 August 1783) |

|||

* [[Karl Thomas Mozart]] (21 September 1784{{snd}}31 October 1858) |

|||

* Johann Thomas Leopold (18 October{{snd}}15 November 1786) |

|||

* Theresia Constanzia Adelheid Friedericke Maria Anna (27 December 1787{{snd}}29 June 1788) |

|||

* Anna Maria (died soon after birth, 16 November 1789) |

|||

* [[Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart]] (26 July 1791{{snd}}29 July 1844) |

|||

===1782–87=== |

|||

In 1782 and 1783, Mozart became intimately acquainted with the work of [[Johann Sebastian Bach]] and [[George Frideric Handel]] as a result of the influence of [[Gottfried van Swieten]], who owned many manuscripts of the [[Baroque music|Baroque]] masters. Mozart's study of these scores inspired compositions in Baroque style and later influenced his musical language, for example in [[fugue|fugal]] passages in ''[[The Magic Flute|Die Zauberflöte]]'' ("The Magic Flute") and the finale of [[Symphony No. 41 (Mozart)|Symphony No. 41]].{{sfn|Eisen|Sadie|2001}} |

|||

In 1783, Mozart and his wife visited his family in Salzburg. His father and sister were cordially polite to Constanze, but the visit prompted the composition of one of Mozart's great liturgical pieces, the [[Great Mass in C minor|Mass in C minor]]. Though not completed, it was premiered in Salzburg, with Constanze singing a solo part.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=270}} |

|||

Mozart met [[Joseph Haydn]] in Vienna around 1784, and the two composers became friends. When Haydn visited Vienna, they sometimes played together in an impromptu [[string quartet]]. Mozart's [[Haydn Quartets (Mozart)|six quartets dedicated to Haydn]] (K. 387, K. 421, K. 428, K. 458, K. 464, and K. 465) date from the period 1782 to 1785, and are judged to be a response to [[String Quartets, Op. 33 (Haydn)|Haydn's Opus 33]] set from 1781.<ref>See {{harvnb|Barry|2000}} for detailed discussion of the influence of Opus 33 on the "Haydn" quartets.</ref> Haydn wrote, "posterity will not see such a talent again in 100 years"{{sfn|Landon|1990|p=171}} and in 1785 told Mozart's father: "I tell you before God, and as an honest man, your son is the greatest composer known to me by person and repute, he has taste and what is more the greatest skill in composition."<ref>{{harvnb|Mozart|Mozart|1966|p=1331}}. Leopold's letter to his daughter [[Maria Anna Mozart|Nannerl]], 14–16 May 1785.</ref> |

|||

From 1782 to 1785 Mozart mounted concerts with himself as a soloist, presenting three or four new piano concertos in each season. Since space in the theatres was scarce, he booked unconventional venues: a large room in the Trattnerhof apartment building, and the ballroom of the Mehlgrube restaurant.<ref name="solomon 1995 293">{{harvnb|Solomon|1995|p=293}}</ref> The concerts were very popular, and [[Piano concertos by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|his concertos]] premiered there are still firm fixtures in his repertoire. Solomon writes that during this period, Mozart created "a harmonious connection between an eager composer-performer and a delighted audience, which was given the opportunity of witnessing the transformation and perfection of a major musical genre".<ref name="solomon 1995 293" /> |

|||

With substantial returns from his concerts and elsewhere, Mozart and his wife adopted a more luxurious lifestyle. They moved to an expensive apartment, with a yearly rent of 460 florins.<ref name="solomon 1995 298">{{harvnb|Solomon|1995|p=298}}</ref> Mozart bought a fine [[fortepiano]] from [[Anton Walter]] for about 900 florins, and a [[Carom billiards|billiard]] table for about 300.<ref name="solomon 1995 298" /> The Mozarts sent their son [[Karl Thomas Mozart|Karl Thomas]] to an expensive boarding school{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=430}}{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=578}} and kept servants. During this period Mozart saved little of his income.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|loc=§27}}{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=431}} |

|||

On 14 December 1784, Mozart became a [[Freemasonry|Freemason]], admitted to the lodge Zur Wohltätigkeit ("Beneficence").{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=321}} Freemasonry played an essential role in the remainder of Mozart's life: he attended meetings, a number of his friends were Masons, and on various occasions, he composed Masonic music, e.g. the [[Maurerische Trauermusik]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Rushton|first=Julian|author-link=Julian Rushton|title=Mozart: An Extraordinary Life|page=67|publisher=[[ABRSM#ABRSM publications|Associated Board of the Royal School of Music]]|year=2005}}</ref> |

|||

====1786–87: Return to opera==== |

|||

[[File:Mozartův klavír 1.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Fortepiano]] played by Mozart in 1787, Czech Museum of Music, Prague<ref>{{cite news|title=Czech Museum of Music to display "Mozart" piano|url=https://www.radio.cz/en/section/curraffrs/czech-museum-of-music-to-display-mozart-piano|website=Radio Praha|access-date=14 December 2018|date=31 January 2007|archive-date=2 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191202105327/https://www.radio.cz/en/section/curraffrs/czech-museum-of-music-to-display-mozart-piano|url-status=live}}</ref>]] |

|||

Despite the great success of ''[[Die Entführung aus dem Serail]]'', Mozart did little operatic writing for the next four years, producing only two unfinished works and the one-act ''[[Der Schauspieldirektor]]''. He focused instead on his career as a piano soloist and writer of concertos. Around the end of 1785, Mozart moved away from keyboard writing<ref>{{harvnb|Solomon|1995}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=September 2010}} and began his famous operatic collaboration with the [[Libretto|librettist]] [[Lorenzo Da Ponte]]. The year 1786 saw the successful premiere of ''[[The Marriage of Figaro|Le nozze di Figaro]]'' in Vienna. Its reception in [[Mozart and Prague|Prague]] later in the year was even warmer, and this led to a second collaboration with Da Ponte: the opera ''[[Don Giovanni]]'', which premiered in October 1787 to acclaim in Prague, but less success in Vienna during 1788.{{sfn|Freeman|2021|pp=131–168}} The two are among Mozart's most famous works and are mainstays of operatic repertoire today, though at their premieres their musical complexity caused difficulty both for listeners and for performers. These developments were not witnessed by Mozart's father, who had died on 28 May 1787.<ref>{{cite book|last=Palmer|first=Willard|author-link=Willard Palmer|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Bs0cSyGLaNMC&pg=PA4|title=W. A. Mozart: An Introduction to His Keyboard Works|page=4|publisher=Alfred Music Publishing|date= 2006|isbn=978-0-7390-3875-8}}</ref> |

|||

In December 1787, Mozart finally obtained a steady post under aristocratic patronage. Emperor Joseph II appointed him as his "chamber composer", a post that had fallen vacant the previous month on the death of [[Christoph Willibald Gluck|Gluck]]. It was a part-time appointment, paying just 800 florins per year, and required Mozart only to compose dances for the annual balls in the [[Hofburg Palace|Redoutensaal]] (see ''[[Mozart and dance]]''). This modest income became important to Mozart when hard times arrived. Court records show that Joseph aimed to keep the esteemed composer from leaving Vienna in pursuit of better prospects.<ref>{{harvnb|Solomon|1995|pp=423–424}}</ref>{{ref|1=A more recent view, {{harvnb|Wolff|2012}}, is that Mozart's position was a more substantial one than is traditionally maintained, and that some of Mozart's chamber music from this time was written as part of his imperial duties.}} |

|||

In 1787, the young [[Ludwig van Beethoven]] spent several weeks in Vienna, hoping to study with Mozart.{{sfn|Haberl|2006|pp=215–255}} No reliable records survive to indicate whether the [[Beethoven and Mozart|two composers]] ever met. |

|||

===Later years=== |

|||

====1788–90==== |

|||

{{see also|Mozart's Berlin journey}} |

|||

[[File:Mozart drawing Doris Stock 1789.jpg|thumb|upright|Drawing of Mozart in [[silverpoint]], made by [[Dora Stock]] during Mozart's visit to Dresden, April 1789]] |

|||

Toward the end of the decade, Mozart's circumstances worsened. Around 1786 he had ceased to appear frequently in public concerts, and his income shrank.<ref name="sadie 1998 6">{{harvnb|Sadie|1998|loc=§6}}</ref> This was a difficult time for musicians in Vienna because of the [[Austro-Turkish War (1787–1791)|Austro-Turkish War]]: both the general level of prosperity and the ability of the aristocracy to support music had declined. In 1788, Mozart saw a 66% decline in his income compared to his best years in 1781.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|pp=427, 432}} |

|||

By mid-1788, Mozart and his family had moved from central Vienna to the suburb of [[Alsergrund]].<ref name="sadie 1998 6" /> Although it has been suggested that Mozart aimed to reduce his rental expenses by moving to a suburb, as he wrote in his letter to [[Michael von Puchberg]], Mozart had not reduced his expenses but merely increased the housing space at his disposal.{{sfn|Lorenz|2010}} Mozart began to borrow money, most often from his friend and fellow mason Puchberg; "a pitiful sequence of letters pleading for loans" survives.{{sfn|Sadie|1980|loc=vol. 12, p. 710}} Maynard Solomon and others have suggested that Mozart was suffering from depression, and it seems his musical output slowed.{{sfn|Steptoe|1990|p=208}} Major works of the period include the last three symphonies (Nos. [[Symphony No. 39 (Mozart)|39]], [[Symphony No. 40 (Mozart)|40]], and [[Symphony No. 41 (Mozart)|41]], all from 1788), and the last of the three Da Ponte operas, ''[[Così fan tutte]]'', premiered in 1790. |

|||

Around this time, Mozart made some long journeys hoping to improve his fortunes, visiting Leipzig, Dresden, and Berlin in the spring of 1789, and [[Frankfurt]], Mannheim, and other German cities in 1790. |

|||

====1791==== |

|||

Mozart's last year was, until his final illness struck, a time of high productivity—and by some accounts, one of personal recovery.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|loc=§30}}{{efn|1=More recently, {{harvnb|Wolff|2012}} has forcefully advocated a view of Mozart's career at the end of his life as being on the rise, interrupted by his sudden death.}} He composed a great deal, including some of his most admired works: the opera ''[[The Magic Flute]]''; the final piano concerto ([[Piano Concerto No. 27 (Mozart)|K. 595 in B{{music|flat}}]]); the [[Clarinet Concerto (Mozart)|Clarinet Concerto]] K. 622; the last in his series of string quintets ([[String Quintet No. 6 (Mozart)|K. 614 in E{{music|flat}}]]); the motet [[Ave verum corpus (Mozart)|Ave verum corpus]] K. 618; and the unfinished [[Requiem (Mozart)|Requiem]] K. 626. |

|||

Mozart's financial situation, a source of anxiety in 1790, finally began to improve. Although the evidence is inconclusive,<ref name="solomon 1995 477">{{harvnb|Solomon|1995|p=477}}</ref> it appears that wealthy patrons in Hungary and Amsterdam pledged annuities to Mozart in return for the occasional composition. He is thought to have benefited from the sale of dance music written in his role as Imperial chamber composer.<ref name="solomon 1995 477" /> Mozart no longer borrowed large sums from Puchberg and began to pay off his debts.<ref name="solomon 1995 477" /> |

|||

He experienced great satisfaction in the public success of some of his works, notably ''The Magic Flute'' (which was performed several times in the short period between its premiere and Mozart's death){{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=487}} and the Little Masonic Cantata K. 623, premiered on 17 November 1791.<ref>And not as previously stated on 15 November; see {{harvnb|Abert|2007|p=1307, fn 9}}</ref> |

|||

====Final illness and death==== |

|||

{{Main|Death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart}} |

|||

[[File:Wolfgang-amadeus-mozart 1.jpg|thumb|upright|Posthumous painting by [[Barbara Krafft]] in 1819]]Mozart fell ill while in Prague for the premiere, on 6{{nbsp}}September 1791, of his opera ''[[La clemenza di Tito]]'', which was written in that same year on commission for Emperor [[Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor|Leopold II]]'s coronation festivities.{{sfn|Freeman|2021|pp=193–230}} He continued his professional functions for some time and conducted the premiere of ''[[The Magic Flute]]'' on 30 September. His health deteriorated on 20 November, at which point he became bedridden, suffering from swelling, pain, and vomiting.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=491}} |

|||

Mozart was nursed in his final days by his wife and her youngest sister, and was attended by the family doctor, Thomas Franz Closset. He was mentally occupied with the task of finishing his [[Requiem (Mozart)|Requiem]], but the evidence that he dictated passages to his student [[Franz Xaver Süssmayr]] is minimal.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|pp=493, 588}} |

|||

Mozart died in his home on {{death date and age|df=yes|1791|12|05|1756|01|27}} at 12:55 am.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.classicfm.com/composers/mozart/guides/mozarts-final-year-1791/|title=Mozart's final year and death—1791|publisher=[[Classic FM (UK)]]|access-date=17 December 2017|archive-date=19 December 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171219114033/http://www.classicfm.com/composers/mozart/guides/mozarts-final-year-1791/|url-status=live}}</ref> The ''[[The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians|New Grove]]'' describes his funeral: |

|||

<blockquote>Mozart was interred in a common grave, in accordance with contemporary Viennese custom, at the [[St. Marx Cemetery]] outside the city on 7{{nbsp}}December. If, as later reports say, no mourners attended, that too is consistent with Viennese burial customs at the time; later [[Otto Jahn]] (1856) wrote that [[Antonio Salieri|Salieri]], [[Franz Xaver Süssmayr|Süssmayr]], [[Gottfried van Swieten|van Swieten]] and two other musicians were present. The tale of a storm and snow is false; the day was calm and mild.{{sfn|Sadie|1980|loc=vol. 12, p. 716}}</blockquote> |

|||

The expression "common grave" refers to neither a communal grave nor a pauper's grave, but an individual grave for a member of the common people (i.e., not the aristocracy). Common graves were subject to excavation after ten years; the graves of aristocrats were not.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.aproposmozart.com/Brauneis%20--%20Dies%20irae.rev.Index.pdf|author=Walther Brauneis|author-link=:de:Walther Brauneis|title=Dies irae, dies illa—Day of wrath, day of wailing: Notes on the commissioning, origin and completion of Mozart's Requiem (KV 626)|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140407071543/http://www.aproposmozart.com/Brauneis%20--%20Dies%20irae.rev.Index.pdf|archive-date=7 April 2014}}</ref> |

|||

The cause of Mozart's death is not known with certainty. The official record of ''hitziges Frieselfieber'' ("severe miliary fever",<!--this is not a typo--> referring to a rash that looks like [[millet|millet seeds]]) is more a symptomatic description than a diagnosis. Researchers have suggested more than a hundred causes of death, including acute [[rheumatic fever]],<ref name="Wakin 2010"/><ref>{{cite news|last=Crawford|first=Franklin|date=14 February 2000|title=Foul play ruled out in death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|url=http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2000-02/CUNS-Fpro-1402100.php|newspaper=EurekAlert!|publisher=[[American Association for the Advancement of Science]]|access-date=26 April 2014|archive-date=26 April 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140426233455/http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2000-02/CUNS-Fpro-1402100.php|url-status=dead}}</ref> [[Streptococcus|streptococcal]] infection,<ref>{{cite news|author=Becker, Sander|date=20 August 2009|url=http://www.trouw.nl/tr/nl/4324/Nieuws/article/detail/1152870/2009/08/20/Voorlopig-is-Mozart-bezweken-aan-streptokok.dhtml|title=Voorlopig is Mozart bezweken aan streptokok|trans-title=For the time being Mozart succumbed to streptococcus|work=[[Trouw]]|access-date=25 April 2014|archive-date=24 April 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140424131007/http://www.trouw.nl/tr/nl/4324/Nieuws/article/detail/1152870/2009/08/20/Voorlopig-is-Mozart-bezweken-aan-streptokok.dhtml|url-status=live}}.</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Bakalar|first=Nicholas|date=17 August 2009|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/18/health/18mozart.html|title=What Really Killed Mozart? Maybe Strep|newspaper=[[The New York Times]]|access-date=24 April 2014|archive-date=30 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140630061249/http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/18/health/18mozart.html|url-status=live}}</ref> [[trichinosis]],<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=648393|title=Special Article: What Really Killed Mozart?|journal=[[JAMA Internal Medicine]]|volume=161|issue=11|pages=1381–1389|date=11 June 2001|last=Hirschmann|first=Jan V.|doi=10.1001/archinte.161.11.1381|pmid=11386887|access-date=26 January 2016|archive-date=2 February 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160202071620/http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=648393|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|url=http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=211378|journal=[[JAMA Internal Medicine]]|volume=162|issue=8|pages=946; author reply 946–947|title=Editor's Correspondence: Trichinellosis Is Unlikely to Be Responsible for Mozart's Death|date=22 April 2002|last=Dupouy-Camet|first=Jean|doi=10.1001/archinte.162.8.946|pmid=11966352|type=Critical comment and reply|access-date=26 January 2016|archive-date=2 February 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160202090810/http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=211378|url-status=live}}</ref> [[influenza]], [[mercury poisoning]], and a rare [[Nephrology|kidney]] ailment.<ref name="Wakin 2010">{{harvnb|Wakin|2010}}</ref> |

|||

Mozart's modest funeral did not reflect his standing with the public as a composer; memorial services and concerts in Vienna and Prague were well attended. Indeed, in the period immediately after his death, his reputation rose substantially. Solomon describes an "unprecedented wave of enthusiasm"<ref name="Solomonp499">{{harvnb|Solomon|1995|p=499}}</ref> for his work; [[Biographies of Mozart|biographies were written]] first by [[Friedrich Schlichtegroll|Schlichtegroll]], [[Franz Xaver Niemetschek|Niemetschek]], and [[Georg Nikolaus von Nissen|Nissen]], and publishers vied to produce complete editions of his works.<ref name="Solomonp499" /> |

|||

==Appearance and character== |

|||

[[File:Mozart-1783-lange.jpg|thumb|Detail of portrait of Mozart by his brother-in-law Joseph Lange]] |

|||

Mozart's physical appearance was described by tenor [[Michael Kelly (tenor)|Michael Kelly]] in his ''Reminiscences'': "a remarkably small man, very thin and pale, with a profusion of fine, fair hair of which he was rather vain". His early biographer Niemetschek wrote, "there was nothing special about [his] physique.{{nbsp}}... He was small and his countenance, except for his large intense eyes, gave no signs of his genius." His facial complexion was pitted, a reminder of his [[Mozart and smallpox|childhood case of smallpox]].<ref name=Telegraph /> Of his voice, his wife later wrote that it "was a tenor, rather soft in speaking and delicate in singing, but when anything excited him, or it became necessary to exert it, it was both powerful and energetic."{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=308}} |

|||

He loved elegant clothing. Kelly remembered him at a rehearsal: {{nowrap|"[He]}} was on the stage with his crimson [[pelisse]] and gold-laced [[Bicorne|cocked hat]], giving the time of the music to the orchestra." Based on paintings that researchers were able to find of Mozart, he seemed to wear a white wig for most of his formal occasions—researchers of the [[Salzburg Mozarteum]] declared that only one of his fourteen portraits they had found showed him without his wig.<ref name= Telegraph>{{cite news|title=Discovered, new Mozart portrait that shows musician without his wig|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/9797143/Discovered-new-Mozart-portrait-that-shows-musician-without-his-wig.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/9797143/Discovered-new-Mozart-portrait-that-shows-musician-without-his-wig.html |archive-date=10 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live|website=[[The Daily Telegraph|The Telegraph]]|access-date=7 May 2018|date=11 January 2013}}{{cbignore}}</ref> |

|||

Mozart usually worked long and hard, finishing compositions at a tremendous pace as deadlines approached. He often made sketches and drafts; unlike Beethoven's, these are mostly not preserved, as his wife sought to destroy them after his death.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=310}} |

|||

Mozart lived at the center of the Viennese musical world, and knew a significant number and variety of people: fellow musicians, theatrical performers, fellow Salzburgers, and aristocrats, including some acquaintance with Emperor [[Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor|Joseph II]]. Solomon considers his three closest friends to have been Gottfried von Jacquin, Count August Hatzfeld, and Sigmund Barisani; others included his elder colleague [[Joseph Haydn]], singers [[Franz Xaver Gerl]] and [[Benedikt Schack]], and the horn player [[Joseph Leutgeb]]. Leutgeb and Mozart carried on a kind of friendly mockery, often with Leutgeb as the butt of Mozart's [[practical joke]]s.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|loc=§20}} |

|||

He enjoyed [[billiards]], dancing, and kept pets, including a canary, a [[Mozart's starling|starling]], a dog, and a horse for recreational riding.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=319}} He had a startling fondness for [[Mozart and scatology|scatological humour]], which is preserved in his surviving letters, notably those written to his cousin [[Maria Anna Thekla Mozart]] around 1777–1778, and in his correspondence with his sister and parents.{{sfn|Solomon|1995|p=169}} Mozart also wrote scatological music, a series of [[Canon (music)|canons]] that he sang with his friends.<ref>A list of the canons may be found at [[Mozart and scatology#In music]].</ref> He had an ear for languages, and having traveled all over Europe as a boy, was fluent in Latin, Italian, and French in addition to his native Salzburg dialect of German. He possibly also understood and spoke some English, having jokingly written "You are an ass" after his 19-year-old student [[Thomas Attwood (composer)|Thomas Attwood]] made a thoughtless mistake on his exercise papers.<ref>[https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/brexit-news-mozart-multilingual-hidden-talents-68158/ "The hidden talents of Wolfgang Mozart"] by [[Peter Trudgill]], 10 February 2020, ''[[The New European]]''</ref><ref>[https://bll01.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma990027027660100000&context=L&vid=44BL_INST:BLL01&lang=en&search_scope=Not_BL_Suppress&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=LibraryCatalog&query=any,contains,Thomas%20Attwood&facet=creator,include,Mozart,%20Wolfgang%20Amadeus&offset=0 "''Thomas Attwood's studies with Mozart''"] by [[C. B. Oldman|Cecil Bernard Oldman]], 1925</ref> |

|||

Mozart [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the Catholic Church|was raised a Catholic]] and remained a devout member of the Church throughout his life.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Goldstein|first1=Jack|title=101 Amazing Mozart Facts|date=2013|publisher=Andrews UK Limited}}</ref>{{sfn|Abert|2007|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=l6I6BwTMJ3sC&pg=PA743 743]}} He embraced the teachings of [[Freemasonry]] in 1784.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Wolfgang-Amadeus-Mozart/The-central-Viennese-period | title=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Viennese Composer, Operas, Symphonies|encyclopedia=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]}}</ref> |

|||

==Works, musical style, and innovations== |

==Works, musical style, and innovations== |

||

{{mainarticle|1=List of compositions by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart}} |

|||

{{See also|List of compositions by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|List of operas by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart's compositional method}} |

|||

Mozart, along with Haydn and [[Beethoven]], was a central representative of the [[Classical music era|classical]] style. His works spanned the period during which that style transformed from a predominantly simple musical language, as exemplified by the ''stile [[galant]]'' of his contemporaries such as [[Giovanni Battista Sammartini|Sammartini]] and [[Johann Stamitz]], to a mature style which began to incorporate some of the [[counterpoint|contrapuntal]] complexities of the late [[Baroque music|Baroque]], complexities against which the ''galant'' style was a reaction. Mozart's own stylistic development closely paralleled the maturing of the classical style as a whole. In addition, he was a prolific composer and wrote in almost every major genre, including [[symphony]], [[opera]], the solo [[concerto]], chamber music including [[string quartet]] and [[string quintet]]s, and the keyboard sonata. While none of these genres were new, the piano concerto was almost single-handedly developed and popularized by Mozart. Mozart also wrote a great deal of religious music including [[mass (music)|mass]]es. He also composed many dances, [[divertimento|divertimenti]], serenades, and other forms of light entertainment. |

|||

===Style=== |

|||

{{Listen|type=music|image=none|help=no |

|||

The central traits of the classical style can all be identified in Mozart's music. Clarity, balance, transparency, and uncomplicated harmonic language are his hallmark, although in his later works he explored chromatic harmony to a degree rare at the time.<!--I'm not sure that this is true; his harmonic language remained reasonably stable throughout his adulthood, didn't it?--> <!--No, it did not. Have a look at his composition list after K600 versus that between, say, K200 and K300--> Mozart is commonly named along with Schubert as having a gift for pure, simple, and memorable melody, and to many listeners this is his most definitive characteristic. |

|||

|filename=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Symphony 40 g-moll - 1. Molto allegro.ogg |

|||

|title=Symphonie Nr. 40 G minor, K. 550. Movement: 1. Molto allegro |

|||

|description= |

|||

|filename2=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Don Giovanni - Overtüre.ogg |

|||

|title2=Overture to ''Don Giovanni'' |

|||

|description2=Both performed by the Fulda Symphonic Orchestra, conductor: Simon Schindler}} |

|||

Mozart's music, like [[Joseph Haydn|Haydn]]'s, stands as an archetype of the [[Classical period (music)|Classical style]]. At the time he began composing, European music was dominated by the ''[[galant|style galant]]'', a reaction against the highly evolved intricacy of the [[Baroque music|Baroque]]. Progressively, and in large part at the hands of Mozart himself, the [[counterpoint|contrapuntal]] complexities of the late Baroque emerged once more, moderated and disciplined by new [[Musical form|forms]], and adapted to a new aesthetic and social milieu. Mozart was a versatile composer, and wrote in every major genre, including [[symphony]], opera, the solo concerto, chamber music including [[string quartet]] and [[string quintet]], and the piano [[sonata]]. These forms were not new, but Mozart advanced their technical sophistication and emotional reach. He almost single-handedly developed and popularized the Classical [[Mozart piano concertos|piano concerto]]. He wrote a great deal of [[religious music]], including large-scale [[mass (music)|masses]], as well as dances, [[divertimento|divertimenti]], [[serenade]]s, and other forms of light entertainment.{{sfn|Grove|1954|pages=[https://archive.org/details/grovesdictionary01grov/page/958 958–982]}} |

|||

The central traits of the Classical style are all present in Mozart's music. Clarity, balance, and transparency are the hallmarks of his work, but simplistic notions of its delicacy mask the exceptional power of his finest masterpieces, such as the [[Piano Concerto No. 24 (Mozart)|Piano Concerto No. 24]] in C minor, K. 491; the [[Symphony No. 40 (Mozart)|Symphony No. 40]] in G minor, K. 550; and the opera ''[[Don Giovanni]]''. [[Charles Rosen]] makes the point forcefully: |

|||

From his earliest life Mozart had a gift for imitating the music he heard; since he travelled widely, he acquired a rare collection of experiences from which to create his unique compositional language. When he went to London as a child, he met [[Johann Christian Bach|JC Bach]] and heard his music; when he went to Paris, Mannheim, and Vienna, he heard the work of composers active there, as well as the spectacular Mannheim orchestra; when he went to Italy, he encountered the [[Italian overture]] and the [[opera buffa]], both of which were to be hugely influential on his development. Both in London and Italy, the galant style was all the rage: simple, light music, with a mania for [[cadence|cadencing]], an emphasis on tonic, dominant, and subdominant to the exclusion of other chords, symmetrical phrases, and clearly articulated structures. This style, out of which the classical style evolved, was a reaction against the complexity of late Baroque music. Some of Mozart's early symphonies are essentially [[Italian overture]]s, with three movements running into each other; many are "homotonal" (each movement in the same key, with the slow movement in the tonic minor). Others mimic the works of JC Bach, and others show the simple, [[binary form|rounded binary form]]s commonly being written by composers in Vienna. |

|||

<blockquote>It is only through recognizing the violence and sensuality at the center of Mozart's work that we can make a start towards a comprehension of his structures and an insight into his magnificence. In a paradoxical way, [[Robert Schumann|Schumann]]'s superficial characterization of the [[Symphony No. 40 (Mozart)|G minor Symphony]] can help us to see Mozart's daemon more steadily. In all of Mozart's supreme expressions of suffering and terror, there is something shockingly voluptuous.{{sfn|Rosen|1998|p=324}}</blockquote> |

|||

As Mozart matured, he began to incorporate some features of the abandoned Baroque styles into his music. For example, the [[Symphony No. 29 (Mozart)|Symphony No. 29]] in A Major, K. 201, uses a frankly contrapuntal main theme; in addition, in it he began to experiment with irregular phrase lengths, something a ''galant'' composer such as [[Giovanni Battista Sammartini|Sammartini]] would never have done. Some of his quartets from 1773 have fugal finales, probably influenced by Haydn, who had just published his opus 20 set; the influence of the ''Sturm und Drang'' period in German literature, with its brief foreshadowing of the Romantic era to come, is evident in some of the music of both composers of the time. |

|||

During his last decade, Mozart frequently exploited [[Chromaticism|chromatic]] harmony. A notable instance is his [[String Quartet No. 19 (Mozart)|''String Quartet in C major'', K. 465]] (1785), whose introduction abounds in chromatic suspensions, giving rise to the work's nickname, the "Dissonance" quartet. |

|||

In Mozarts's hands [[sonata form]] transformed from the binary models of the baroque into the fully mature form of his later works, with a multiple-theme exposition, extended, chromatic and contrapuntal development, recapitulation of all themes in the tonic key, and coda.<!--What is crucial here is the use of modulation as the dramatic cornerstone of form; it's not so much melody as key change that is the structural innovation--> |

|||

Mozart had a gift for absorbing and adapting the valuable features of others' music. His travels helped in the forging of a unique compositional language.<ref>{{harvnb|Solomon|1995|loc=ch. 8}}. Discussion of the sources of style as well as his early imitative ability.</ref> In London as a child, he met [[Johann Christian Bach|J. C. Bach]] and heard his music. In Paris, Mannheim, and Vienna he met with other compositional influences, as well as the avant-garde capabilities of the [[Mannheim school|Mannheim orchestra]]. In Italy, he encountered the [[Italian overture]] and [[opera buffa]], both of which deeply affected the evolution of his practice. In London and Italy, the [[galant style]] was in the ascendent: simple, light music with a mania for [[cadence|cadencing]]; an emphasis on tonic, dominant, and subdominant to the exclusion of other harmonies; symmetrical phrases; and clearly articulated partitions in the overall form of movements.{{sfn|Heartz|2003}} Some of Mozart's early symphonies are [[Italian overture]]s, with three movements running into each other; many are [[homotonal]] (all three movements having the same key signature, with the slow middle movement being in the [[Relative key|relative minor]]). Others mimic the works of J. C. Bach, and others show the simple [[binary form|rounded binary forms]] turned out by Viennese composers. |

|||

Throughout his life Mozart switched his focus from writing instrumental music to writing operas, and back again. He wrote operas in each style current in Europe: opera buffa, such as ''[[The Marriage of Figaro]]'' or ''[[Così fan tutte]]''; ''[[opera seria]]'', such as ''[[Idomeneo]]'' or ''[[Don Giovanni]]''; and ''[[singspiel]]'', of which the ''[[The Magic Flute|Magic Flute]]'' is probably the most famous example by any composer. In his later operas, he developed the use of subtle and slight changes of instrumentation, orchestration, and tone colour to express or highlight psychological or emotional states and dramatic shifts. Here his advances in opera and instrumental composing interacted upon one another. The increasing sophistication of his use of the orchestra in his symphonies and concerti served as a resource in his operatic orchestration, and his developing subtlety in using the orchestra to psychological effect in his operas reacted back upon his purely instrumental composition. |

|||

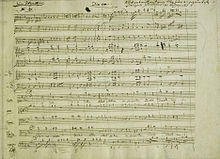

[[File:K626 Requiem Dies Irae.jpg|thumb|Facsimile sheet of music from the Dies Irae movement of the [[Requiem (Mozart)|Requiem Mass in D minor]] (K. 626) in Mozart's handwriting ([[Mozarthaus Vienna|Mozarthaus]], Vienna)]] |

|||

===Influence=== |

|||

As Mozart matured, he progressively incorporated more features adapted from the Baroque. For example, the [[Symphony No. 29 (Mozart)|Symphony No. 29 in A major]] K. 201 has a contrapuntal main theme in its first movement, and experimentation with irregular phrase lengths. Some of his quartets from 1773 have fugal finales, probably influenced by Haydn, who had included three such finales in his recently published [[String Quartets, Op. 20 (Haydn)|Opus 20]] set. The influence of the ''[[Sturm und Drang]]'' ("Storm and Stress") period in music, with its brief foreshadowing of the [[Romanticism|Romantic era]], is evident in the music of both composers at that time. Mozart's [[Symphony No. 25 (Mozart)|Symphony No. 25 in G minor]] K. 183 is another excellent example. |

|||

Mozart would sometimes switch his focus between operas and instrumental music. He produced operas in each of the prevailing styles: [[opera buffa]], such as ''[[The Marriage of Figaro|Le nozze di Figaro]]'', ''[[Don Giovanni]]'', and ''[[Così fan tutte]]''; [[opera seria]], such as ''[[Idomeneo]]''; and [[Singspiel]], of which ''[[The Magic Flute|Die Zauberflöte]]'' is the most famous example by any composer. In his later operas, he employed subtle changes in instrumentation, orchestral texture, and [[Timbre|tone colour]], for emotional depth and to mark dramatic shifts. Here his advances in opera and instrumental composing interacted: his increasingly sophisticated use of the orchestra in the symphonies and concertos influenced his operatic orchestration, and his developing subtlety in using the orchestra to psychological effect in his operas was in turn reflected in his later non-operatic compositions.{{sfn|Einstein|1965|p={{page needed|date=July 2020}}}} |

|||

Many important composers since Mozart's time have worshipped or at least been in awe of Mozart. [[Gioacchino Rossini|Rossini]] averred, "He is the only musician who had as much knowledge as genius, and as much genius as knowledge." [[Ludwig van Beethoven|Beethoven]] told his pupil [[Ferdinand Ries|Ries]] that he (Beethoven) would never be able to think of a melody as great as a certain one in the first movement of Mozart's [[Piano Concerto No. 24 (Mozart)|Piano Concerto No. 24]]. Beethoven also paid homage to Mozart by writing sets of [[theme_and_variations|variations]] on several of his themes: for example, the two sets of variations for cello and piano on themes from Mozart's ''[[The Magic Flute|Magic Flute]]'', and cadenzas to several of Mozart's piano concertos, most notably the [[Piano Concerto No. 20 (Mozart)|Piano Concerto No. 20]], K466 (see below for this system and an explanation). After the only meeting between the two composers, Mozart noted that Beethoven would "give the world something to talk about." As well, [[Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky|Tchaikovsky]] wrote his ''Mozartiana'' in praise of him; and [[Gustav Mahler|Mahler]] died with the name "Mozart" on his lips. The variations theme of the opening movement of [[Piano Sonata No. 11 (Mozart)|the A major piano sonata]] (K331) was used by [[Max Reger]] for his ''Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Mozart'', written in 1914 and among his best-known works in turn. |

|||

== |

===Köchel catalogue=== |

||

{{ |

{{Main|Köchel catalogue}} |

||