Bordeaux (wine region)

| map | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Data | |

| Wine region : | Bordeaux |

| Country : | France |

| Viticulture since: | approx. 2nd century (Roman times - not documented) |

| Area : | > 120,700 hectares in 2002 |

| Production: | approx. 5.7 million hectoliters (2002) |

| Share of quality wine : | > 75% |

The Bordeaux wine-growing region , or Bordelais in French , is the largest contiguous wine-growing region in the world for quality wine . There are around 3,000 wineries called Château that produce the world-famous wines . A differentiated system of subregional and communal appellations and classifications creates a qualitative hierarchy among them . In contrast, the individual layers play a subordinate role. Their place is taken by the château to which they belong.

Typical are the dry, long-lived red wines , which are fruity in the Médoc and softer and fuller in Saint-Émilion and Pomerol . White wine makes up almost 20% of production . Its top is represented by the noble sweet Sauternes and Barsac . The dry white wines with the most character come from the Graves area southeast of Bordeaux. Since 1991 there has also been an appellation for sparkling wine , the Crémant de Bordeaux .

In 2002, a total of 5.74 million hectoliters of quality wine were produced on a good 120,000 hectares of cultivation area .

Geography, soil and climate

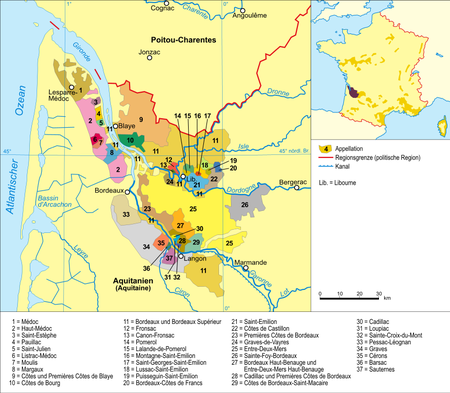

The wine-growing region of Bordeaux includes the locations of the Gironde department in southwestern France that are suitable for quality viticulture . It is located at the mouth of the Garonne and Dordogne rivers at 45 degrees north latitude. The region can be divided into five distinctly different areas:

- The Médoc begins north of Bordeaux and stretches for 70 km on the left bank of the Gironde .

- The Graves begin south of Bordeaux and occupy the southern bank of the Garonne.

- The Entre-Deux-Mers is the hill country between Garonne and Dordogne.

- The Libournais describes the area around the town of Libourne on the right bank of the Dordogne.

- To the northwest of it are Blayais and Bourgeais north of the confluence of the Dordogne and Garonne.

In summary, Médoc and Graves are also referred to as the "Left Bank" and the Libournais as the "Right Bank".

The landscape of the Bordelais rests on a huge limestone plinth from the Tertiary . However, this does not appear everywhere, but is mostly covered by ice-age deposits of sand and gravel. They were brought in from the Isle, Dordogne and Garonne rivers. In the Médoc, they can be several meters thick. These gravel and sand tops allow the vines to take root deeply with excellent drainage. Most of the top wines, the Grands Crus, grow on them . The deeper soils in the immediate vicinity of the rivers ( Palus ), on the other hand, are unsuitable for quality viticulture. In Libournais the situation is more complicated. In Saint-Émilion, the limestone plateau also offers excellent conditions for the vines. Other top plants grow there on molasses , in neighboring Pomerol partly on gravel sand, but also on clay soils. Remarkably, there are also some top-quality wines that are grown on soils that are soaked through. This is the case for some châteaus from Pomerol, Graves and Sauternes.

The nearby Atlantic ensures a mild, balanced climate without extreme temperature fluctuations. The large watercourses and the extensive forest area of the Landes also have a balancing function. However, the different locations (hillside and terrain) create many areas with their own microclimate.

Frost-free winters, humid spring months and sunny summers from July to October are usually characteristic. The average duration of sunshine per year is approx. 2,000 hours with a rainfall of approx. 900 mm. However, the weather varies greatly from year to year, so that the quality of the vintages is very different. In order for a great vintage to emerge, the following requirements must be met in the growing season from April 1 to September 30:

- Sum of the average temperatures at least 3100 ° C

- At least 15 hot days (maximum temperature over 30 ° C)

- Rainfall between 250 and 350 mm

- At least 1250 hours of sunshine .

Since the grape harvest often extends well into autumn, the weather in October still plays an important role in the quality of a vintage.

Grape varieties

Bordeaux wines are typically cuvées of several individually vinified plots and grape varieties . The artful assemblage of the different parts serves to emphasize the specific character of the terroir and the wine style of the chateau . As a rule, there are at least two grape varieties with a varying composition depending on the weather in a year, often three to five that go into a wine. The grape varieties are never mentioned on a Bordeaux label, but the wine owes its reputation not least to the almost exclusive cultivation of varieties with high quality potential.

The famous red wine from Bordeaux is mainly made from three grape varieties: Cabernet Sauvignon , Merlot and Cabernet Franc . Petit Verdot and Malbec play a supporting role . The Carménère , from which the Cabernet varieties and Merlot presumably originate, has largely disappeared after the phylloxera crisis . The most widely grown white variety is the Sémillon , which owes this position to its excellent suitability for producing noble sweet wines. Dry white wine is mainly made from Sauvignon Blanc , but there are also cuvées in which the Sémillon dominates. In addition, Muscadelle , Ugni Blanc and Colombard also play a role, although only the first of these three varieties in top plants.

Appellations

Appellation hierarchy

Bordeaux has a highly differentiated system of over 50 appellations (AOC; A ppellation d ' O rigine C ontrôlée is a protective seal for the controlled origin ). In a somewhat coarser way, three levels can be distinguished, which express a clear hierarchy. The following rule applies: the smaller the area to which the appellation refers, the higher the quality, reputation and price level of the respective wines.

- The regional appellations Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur apply to the entire Gironde department and form the basis with around 57% of total production.

- Above this are the subregional appellations , each of which only covers parts of the area: Médoc for red wines from the entire Médoc, Haut-Médoc for the higher-lying southern part, Graves for red and white wines from the area south of Garonne and Bordeaux, Entre-Deux-Mers for dry white wines and finally the Côtes de Bordeaux, which are mainly located on the right bank of the Dordogne : Côtes de Bourg , Côtes de Blaye , Premières Côtes de Bordeaux , Côtes de Bordeaux-Saint-Macaire , Côtes de Castillon and Côtes-de-Francs. They represent a good 27% of Bordeaux wines.

- The top is formed by the communal appellations , which each refer to only one or a few neighboring communes. The most famous and most expensive wines come from these. Margaux , Moulis , Listrac , Saint-Julien , Pauillac , Saint-Estèphe in the Médoc as well as Saint-Émilion (Saint-Émilion and Saint-Émilion Grand Cru) and Pomerol with their "satellites" Montagne-Saint-Émilion , Lussac apply exclusively to red wine -Saint-Émilion , Puisseguin-Saint-Émilion , Saint-Georges-Saint-Émilion , Lalande-de-Pomerol , Fronsac and Canon-Fronsac in Libournais. Red and white wines are produced in Pessac-Léognan, immediately south of Bordeaux, while Sauternes , Barsac and Cérons south of the Garonne as well as Cadillac , Loupiac , Sainte-Croix-du-Mont and Sainte-Foy-Bordeaux north of the river make noble sweet white wines. The municipal appellations account for almost 16% of total production.

In the case of communal appellations, it is not mandatory that all vineyards are located on the territory of the respective commune. Grapes from neighboring, but equivalent, municipalities may also be used. However, the wine may only ever be sold under the name of an appellation. For example, estates from Pauillac also own vineyards in the neighboring municipality of Saint-Julien. In principle, wine from an excellent municipality can of course also be sold under a subregional appellation or as “Bordeaux”. However, due to the higher market value, every winemaker will bottle his wine under the higher-ranking appellation if possible, provided the stricter conditions are also met. The Château d'Arsac therefore produces both a Margaux and a Haut-Médoc. The latter comes from the vineyards outside the AOC Margaux area.

If an appellation applies exclusively to white or red wine, other wine may only be sold under the subregional or regional designation approved for it. The red wines of the municipalities of Barsac and Sauternes with their noble sweet top-class wines are simply “Graves”, and the very high-quality white Pavillon Blanc of the famous Château Margaux is even just a “Bordeaux”.

Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur

More than half of the production of Bordeaux is accounted for by the regional appellations Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur , with dry white wine the share is even over 72%. The formal requirements are the lowest here. All locations in the Gironde department that are suitable for quality viticulture are permitted. Only moist peat soils and the floodplain of the rivers are excluded. The permitted basic yield is 65 hectoliters per hectare for white Bordeaux and 55 for red and rosé wine. Since 1974 the planting density has only been a low 2,000 vines per hectare. This density of plants enables a Lenz-Moser education of the vines and thus a simple mechanized cultivation of the vineyards.

The grape varieties permitted for red wine are Merlot , Cabernet Sauvignon , Cabernet Franc , Carménère , Malbec and Petit Verdot . In practice, only the first three are important, with Merlot making up the largest proportion. The minimum alcohol content must be 10% by volume, with the must having a sugar content of at least 178 g / l. The regional AOC provides for two different types of rosé wine. In addition to the classic Bordeaux Rosé , a regional specialty is Bordeaux Clairet , a light red, light red wine.

For white wine, Sémillon , Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadelle are permitted as the main grape varieties and Merlot Blanc , Colombard , Mauzac , Ondenc and Ugni Blanc as complementary varieties with a maximum proportion of 30%. In the dry white wine, the Sauvignon predominates, the complementary varieties hardly play a role today. If the residual sugar content is less than 4 g / l, the addition Sec is mandatory. The production of white Bordeaux AOC has been declining since the mid-1970s, the amount sank from 783,000 hl in 1992 to 400,700 hl in 2002. In contrast, red wine production rose from 2.6 to around 2.85 million hectoliters in the same period .

The Bordeaux supérieur has to meet higher formal requirements. In fact, the appellation is mainly used for strong, storable red wines, while red Bordeaux AOC is more fruity and to drink young. The basic yield is set at 40 hl / ha, plus the age-dependent surcharges. The minimum alcohol content of red wine must be 10.5% by volume, white wine even have 11.5% by volume with at least 212 g / l sugar content of the must. White Bordeaux supérieur is a wine with unfermented residual sugar, but is only produced on approx. 50 hectares (as of 2003).

The regional appellation also includes the wines marketed under the designations Bordeaux Haut-Benauge (only for white wine) and Bordeaux Côtes de Francs (for white and red wine). They may only be produced in the municipalities approved for this purpose. The Haut-Benauge is located in the southern part of the Entre-Deux-Mers , east of the Premières Côtes . In contrast to the Entre-Deux-Mers Haut-Benauge , the Bordeaux Haut-Benauge must have a higher must weight and not be developed dry. In practice, however, it is of little importance.

In contrast, the Côtes de Francs have a significant production volume. The relatively small area (536 ha) is located in the east of the Libournais on the border with the Dordogne department . Here the requirements with yield limits of 50 hl / ha and a minimum alcohol content of 11% by volume are higher for red wine. For dry white wine, even 11.5% by volume must be achieved, and sweet white wines are also included in the appellation. However, production is concentrated on red wines, of which 22,781 hl were produced in 2002, while only 284 hl were white wine.

The Libournais

The Libournais area includes a large part of the so-called right bank. The Libournais vineyards are crossed by two rivers, Isle and Barbanne.

Libournais appelation

- Saint-Emilion AOC

- Saint-Emilion Grand Cru AOC

- Montagne-Saint-Emilion AOC

- Puisseguin-Saint-Emilion AOC

- Lussac-Saint-Emilion AOC

- Saint-Georges-Saint-Emilion AOC

- Pomerol AOC

- Lalande-de-Pomerol AOC

- Canon-Fronsac AOC

- Fronsac AOC

- Castillon - Côtes-de-Bordeaux AOC

- Francs - Côtes-de-Bordeaux AOC

Bordeaux wines and their sales

Branded and Château wines

There are basically two types of wines in Bordeaux: branded and estate wines (Château wines). Branded wines are compiled by wine merchants from batches of barrel wine that have been found to be suitable. The aim is to offer a wide range of customers a cuvée that is representative and reliable in terms of quality for the respective appellation. Well-known brands are Mouton-Cadet and Michel Lynch . Most of the cooperatives ' wines also fall into this category , such as La Rose Pauillac , Marquis de Saint-Estèphe or Grand Listrac .

Château wines, on the other hand, come from grapes from a single estate. The château does not have to have a (castle) building, but its name must at least be derived from a field name. The wine can also be prepared in a neighboring estate or in a cooperative winery. The reputation of the château is just as important when judging a Bordeaux wine as the appellation from which it comes. The Union des Grands Crus de Bordeaux , which is responsible for the Grand Crus , is an important sales association .

Crus and their hierarchy

A château produces a single representative wine, the Grand Vin . This forms the cru , the plant. This French name, which stands for the individual vineyard in other regions, was transferred to the Château itself in Bordeaux. The relative homogeneity of the terroirs within the appellations - compared, for example, with the extremely small-scale climates of Burgundy - prevented the differentiation of different locations . In addition, some of the best parcels have been owned by the same owner for centuries. Lots that do not meet the requirements of the producer are marketed as a second wine under a different label. Some châteaus even produce third-party wines .

The systematic establishment of the large Médoc-Châteaus as commercial operations and the general orientation of Bordeaux towards export markets allowed the wines to become international branded articles early on. Due to the different qualities and market values, unofficial hierarchies quickly formed among the wines. In 1855, an official classification of the red wines of the Médoc and the sweet wines of Barsac-Sauternes was created on the basis of sales prices achieved over many years. The original plan was to review and expand this classification at regular intervals. In fact, there has only been one revision since then, the rise of Château Mouton-Rothschild from second to first class in 1973. In 1955, the first classification of the goods of Saint-Emilion took place, which is the only one that is regularly checked. In 1959 the red and white wines of the Graves region were also classified. Thus, Pomerol remains the only top appellation without classification. The classified Château wines can be adorned with the predicate Grand Cru Classé (Great Growth). (For details see classification of Bordeaux wines )

In the Médoc, there is another class with the Crus Bourgeois (bourgeois plants), which since 2003 has in turn been divided into Crus Bourgeois Exceptionnels, Crus Bourgeois Supérieurs and Crus Bourgeois. Finally there are the Crus Artisans , a name that has existed for 150 years and has been revived by a producer group since 1989.

Predicates such as “Grand Cru Classé” or “Cru Bourgeois” are worth real money because the sales price of the wine increases by up to 30%, especially on the domestic market. Against this background, it is understandable that excluded or downgraded châteaus were brought before the administrative courts. In 2007 they overturned both the classification of the Crus Bourgeois and the revision of that of Saint-Émilion.

Although the classifications mark the upper class of Bordeaux, they can by no means be used as the sole criterion for top wines. Goods that were too small or qualitatively in crisis were not taken into account in 1855. Today, numerous Crus Bourgeois are hardly inferior to the Crus Classés in terms of quality and constancy. The same applies to some second wines from leading estates. The hierarchy was definitely mixed up by the garage wines that appeared in the 1990s . They are typically characterized by a high concentration, on the one hand by a strong selection of the grapes, on the other hand by the extreme use of new barrique barrels . The concept of terroir fades into the background. The future must show whether these plants, which are often characterized by strong media interest and speculative price jumps, can establish themselves permanently in the top group.

While the wine world's attention is focused on the grands crus and their equivalents, they account for an estimated 4.5% of Bordeaux's production. Another 5% produce the Crus Bourgeois des Médoc.

Wine trade

Bordeaux has always produced mainly for the national market and export markets. The large production volumes of the châteaus require an efficient distribution system. This is provided by the wine merchants ( Négociants ), mostly based in Bordeaux or Libourne . Brokers ( courtiers ) mediate between them and the châteaus . Today's market for Bordeaux wine is divided into three segments:

- The traditional sales of bottles via wine and food retailers, mail order and increasingly (especially in France itself) via hypermarkets is the most important sales channel. Even large buyers such as retail chains get their bottles mainly from the Négociants in Bordeaux and not directly from the producers. Direct sales to end customers usually only play a subordinate role for the châteaus. The most famous wines, the Grands Crus, are very rarely only sold from the Château, and then not infrequently at "touristy", inflated prices.

- Selling by subscription has become the main distribution channel for the Grands Crus over the past twenty years. Sometimes they sell their entire vintage to the Négociants in the spring following the harvest. The wine is then still in the barrel and is only delivered over a year later after bottling, but the producers get money straight away. The dealers in turn offer their customers the option to subscribe. This is particularly recommended for smaller châteaus, which will later be hard to find in stores, and for purchasing special bottle formats. The price advantage compared to buying after bottling, however, has largely leveled off in recent years.

- A secondary market for older Bordeaux wines has existed for two centuries . Since the large châteaus usually produce several hundred thousand bottles per year, this market is liquid and transparent. Buying at auction can even be considerably cheaper than subscription and offers the opportunity to fill the cellar with matured Bordeaux wines. Older wines are also less subject to speculation.

Price cycles

The prices of the great Bordeaux wines that are new to the market are subject to relatively strong fluctuations from vintage to vintage. On the one hand, these arise on the supply side, as the quality of the vintages and the production quantities can vary greatly. Then there are the movements on the demand side. The Bordeaux prices reflect the economy as well as the fluctuations in the dollar rate. There were strong increases in the course of the dollar bull market from 1983 to 1985 and 1997 to 2000, while the recessions in 1990 and 2001 caused prices to fall. In addition, there are speculative movements, partly fueled by exuberant reporting, such as in the 2000 vintage. The subscription for the 2005 vintage, which took place from mid-2006, also showed enormous swings for the famous top châteaus - with an economically tense market situation for the majority of producers. After calming down in the following years, the 2009 should bring new price records. This is at least indicated by the recent development of the international wine price index Liv-ex 100 , which is dominated by the top Bordeaux.

history

The history of Bordeaux exemplarily demonstrates that top wines are not least the product of socio-economic developments. The central theme is the importance of the city of Bordeaux as a trading center and England's demand for high-quality French wines.

Ancient and Middle Ages

According to Strabo , the port of the ancient “ Burdigala ” already played a central role in the wine trade in the early Roman times - not least with Roman Britain. However, the wine itself came from the "Haut Pays", the southwestern French Oberland (→ Sud-Ouest ). The first vineyards of the Bordelais were planted from the year 56 AD with the onset of the Pax Romana until the reign of Emperor Probus . Both Pliny the Elder and Columella reported successful plantings with vines called Biturica that came from the Spanish region of Navarre . These first non-Mediterranean vineyards of the Romans continued to serve to supply legions stationed in what is now England and Ireland. There were certainly vines in Saint-Emilion , where one of the mansions of the poet Ausonius was located.

After a decline during the migration period with the invasion of the barbarians and Normans, viticulture was only maintained in Catholic communities to celebrate Holy Mass. When the Moors occupied Spain in the 8th century, they cleared all the vines and only kept the table grapes. As a result, the wine-growing region was able to establish itself briefly as a supplier of red wine to the cities of Córdoba, Seville and Valencia, which revived viticulture and trade in the Middle Ages. The city of Bordeaux had the strategic advantage of being able to supply the markets of Northern and Western Europe unhindered by sea. The problem for the red wine region of Bordeaux, however, was that white wines were more popular in Northern Europe. Ships that loaded salt in La Rochelle also had the opportunity to load white wines from the Loire region there.

Bordeaux received a big boost in 1152: through the marriage of Henry Plantagenet , later King Henry II of England, with Eleanor , the heiress of Aquitaine , a large part of western France came under British rule. Her son, the British King Richard I , often held court in Bordeaux. His brother and successor John concluded an agreement with the citizens of Bordeaux that gave them tax breaks in return for the provision of warships. The reconquest of La Rochelle by the King of France in 1224 finally brought Bordeaux a monopoly in the wine trade with England. In the year 1300, the Bordeaux wine fleet consisted of 900 ships. On average in the 14th century it exported 800,000 hectoliters of wine a year, at least half of which to England. The vineyard area of Bordeaux was then an estimated 100,000 hectares. The Hundred Years War brought Aquitaine back to France in 1453, but the French king confirmed Bordeaux's privileges. Particularly important was the right not to let the Haut Pays wine on the market until one's own wine had been sold. Barrel wine was not very durable and was intended for immediate consumption. The Bordeaux was then rather bright red. The English name Claret for Bordeaux wine was derived from the French word "Clairet" . The stronger wines from Cahors and Gaillac served to improve the weak Bordeaux.

The privileges of Bordeaux (le privilège des vins ) were subsequently confirmed by the French kings:

- Louis XI. in 1462

- Charles VIII in October 1483

- Louis XII. in July 1498

- Henry II on June 28, 1551

- Charles IX , 1561

- Henry III. in July 1583

- Henry IV in October 1602

- Louis XIII in June 1610

- Louis XIV in September 1643

- Louis XV in May 1716

Only an edict from Louis XVI. of April 1776 and a law of August 4, 1789 abolished these privileges.

Modern times

It was not until the end of the 17th century that it was discovered how the barrel wine could be preserved by using sulfur. The Bordelais wine merchants quickly developed the art of barrel expansion, and bottling brought another leap in quality. In the 18th century British demand shifted increasingly to the finer wines, while other markets such as the Netherlands and the colonies gained importance for the average product. When the Médoc was drained and made arable, its potential for producing fine wines became apparent, and the Bordelais trading bourgeoisie invested in their own large goods there. Their names still adorn the labels of great wines, for example Ségur ( Château Calon-Ségur ), Brane ( Château Brane-Cantenac ) or Pichon ( Château Pichon-Longueville ). The first Château wine in today's sense was the Haut-Brion , which was enjoyed as early as 1663 by the British naval officer Samuel Pepys , who was known for his posthumously published personal diary . Since the estates in Bordeaux were a bourgeois domain, the estates survived the period of the French Revolution without great expropriations and fragmentation. This continuity is one of the reasons why the notion of location in Bordeaux is irrelevant. The vineyards have always been identified with the château to which they belong.

In the 19th century, the Bordelais, especially the Médoc, experienced its first great heyday. The many classicist and historicist castle buildings that were erected in the wineries during this period are evidence of this. The classification of the Médoc and Sauternes-Barsac wineries on the occasion of the 1855 World's Fair marks a highlight . It fixed the hierarchy of the leading châteaus and gave them a worldwide special position that is still effective today. In the 1860s and 70s there was a real wave of speculation about the wineries. Baron James Mayer Rothschild , then the richest man in France, bought in 1868 for the record sum of 4.4 million gold francs , the Château Lafite . The devastation caused by powdery mildew and phylloxera from 1870 onwards put an end to it . An antidote was quickly found against powdery mildew, the Bordeaux broth . Phylloxera, on the other hand, required the new planting of all vineyards with resistant grafts . Even renowned châteaus sometimes used hybrid vines . At the end of the 19th century, wine-growing in Bordeaux fell into crisis.

20th century

The loss of earnings in the course of the phylloxera crisis and the lack of vigorous wines, as they come from young vineyards, were met with dubious methods by the Bordelais trade. The panhandles resulted in a sharp drop in prices. In order to restore the damaged reputation, a first law was passed in 1911 that delimited the areas of origin. Since then, a Bordeaux has to come from the Gironde department . This was then confirmed in 1936 with the introduction of the Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée . The self-organization of the producers was a further step. Numerous wine cooperatives were founded in the 1930s . At the instigation of the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce, the Crus Bourgeois des Médoc were classified for the first time in 1932, but they only merged into an association in 1962. In order to guarantee the quality and authenticity of his wine, Baron Philippe de Rothschild (→ Château Mouton-Rothschild ) decided in 1924 that in future all wine should be bottled at the castle itself. It was not until the 1960s that this practice became generally accepted among the top goods.

In the worldwide upswing after the Second World War , Bordeaux was able to free itself from the crisis. Quality viticulture benefited not only from the increasing demand for the top wines, but also from the newly created oenology , the science of wine, which was largely developed at the University of Bordeaux and is now being further developed at the Université Bordeaux II . The wine-growing in Bordeaux thus achieved a role model function worldwide. With increasing mechanization, the style of wine gradually changed, albeit cautiously. 1970 marked a turning point as the last classic Bordeaux vintage. In the 1970s, many wines that were too tannic were produced which later did not develop harmoniously. These less good vintages from 1971 to 1974 are therefore often referred to as the Vietnam years - especially in the American wine scene. This refers to the withdrawal of American troops. In the 1980s, under the influence of oenologists like Michel Rolland and critics like Robert Parker, the trend was towards fruity, full-bodied wines.

This decade, with its otherwise rare series of many good vintages, further stimulated worldwide interest in Bordeaux. Large stock corporations acquired châteaus in the Médoc, thus enabling the sometimes extravagant renovation of the facilities. Examples are Axa ( Château Pichon-Longueville-Baron ), Alcatel ( Château Gruaud-Larose ) and Chanel ( Château Rausan-Ségla ). As in the 19th century, the richest French are again striving for the prestige of owning one of the leading châteaus: in 1993, the billionaire François Pinault acquired the Château Latour , and in 1996, after a long tug-of-war , Bernard Arnault was able to incorporate the Château d'Yquem into his LVMH group. In 1998, Arnault teamed up with the Belgian Albert Frère to acquire Château Cheval Blanc for the record sum of 131 million euros . The joint ownership in Saint-Emilion was expanded in the following years to include the châteaus La Tour du Pin Figeac and Quinault L'Enclos .

The growing demand for full-bodied wines met the Libournais wines, which were only able to emancipate themselves from the dominance of the Médoc after the Second World War. The first classification of the Saint-Émilion plants in 1954 was the prelude to this. In the 1980s, top wines such as Château Pétrus and Château Ausone rose in terms of price, and later they were followed by wines such as Château Pavie or garage wines such as Château Le Pin and Château Valandraud . This development is also reflected in the land prices: the value of one hectare of vineyards in Pomerol rose by over 150% in the 1990s, which in 2001 was more than twice as high as in the communal appellations of the Médoc.

Todays situation

At the beginning of the 21st century, a strong polarization characterizes the situation in Bordeaux. While the prices of top wines are likely to reach historic record levels in the promising 2005, the AOC Bordeaux prices for cask wine are in free fall. The minimum price of 1000 euros per tonneau (900 liters) 2005 Bordeaux, set by the Syndicat des Bordeaux, can no longer be enforced on the market. This is due on the one hand to the steadily falling national demand for simple AOC wines, and on the other hand to the tough competition on the international markets. Countries like Argentina , Chile , South Africa and Australia , which also work with the Bordeaux grape variety profile, have massively increased their production in recent years. Of the 7 million hectoliters of the 2004 vintage, the market was only able to absorb 5.5 million hectoliters. The export of Bordeaux wines fell in 2005 by three percent to 1.72 million hectoliters. In Germany, sales of Bordeaux wines fell from around 500,000 hl in 2000 to 316,000 hl in 2005.

A short-term solution is distillation: In the Bordelais, 1.5 million hectoliters of wine were processed into industrial alcohol with the help of EU subsidies in 2005 because they were not for sale. In 2006 the Syndicat plans to take out a loan of 15 million euros for the first time to finance another distillation. In the medium term, a reduction in the area under cultivation appears inevitable. Since the beginning of the 1980s, it had grown from 90,000 to 120,000 hectares, with the increase on balance benefiting exclusively the red grape varieties. The proposed introduction of a country wine, Vin de Pays de la Gironde, would reduce production costs due to the higher yields per hectare, but would aggravate the problem of overproduction. The first action plan, however, met with little response: instead of the planned 10,000, just 2,850 hectares of vineyards were closed in 2006.

All in all, 2006 saw a slight increase in the Bordelais. Production fell to 5.9 million hectoliters in 2005, which helped stabilize prices. Total sales rose by seven percent to € 3.23 billion, mainly thanks to exports to the United States and Asia. Nevertheless, many wineries remain highly indebted and are partly for sale under pressure from the banks. This also applies to châteaus in respected communal appellations, whose production costs are not significantly below those of the leading goods. The high inheritance tax in France is sometimes given as a reason for selling.

The “Top 100” of the Bordelais, the Grands Crus and their equivalent châteaus, don't have to worry anyway. The worldwide, speculatively fueled demand for well-known names and high Parker scores allowed them to sell their 2005 only to those negociants who at the same time undertake to buy the following vintages at the conditions set by the château. With the 2005 vintage, retail prices for Premier Crus des Médoc hit the threshold of 500 euros.

The consequences of this policy are likely to become apparent in the following years. The prices for the by no means high-class 2006er have fallen by only 10-15% after doubling in the previous year. For the mediocre 2007 prices have been further reduced, but are still well above the 2004 prices. At this level, the trade , which is forced to buy, is threatened with huge unsalable stocks, the sale of which will drag on for years, similar to the likewise overpriced 1997. The situation will by no means get any better with the new "vintage of the century" 2009, which is attracting all the interest.

See also

- Viticulture in France

- Classification of Bordeaux wines

- Vintage vintages with comments on the younger Bordeaux vintages

literature

- Hubrecht Duijker , Michael Broadbent : Bordeaux Wine Atlas . Hallwag, Bern / Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-444-10492-8

- Michel Dovaz: Bordeaux. Terre de légende . Assouline, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-84323-024-1 .

- Féret: Bordeaux et ses vins . Féret, Bordeaux 2000, ISBN 2-902416-17-2 .

- René Gabriel : Bordeaux Total . Orell Füssli, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-280-05114-2 .

- Robert Parker : Parker Bordeaux . Gräfe & Unzer, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7742-6580-1 .

Web links

- Comité interprofessionnel du vin de Bordeaux (German)

- bordeauxonline.de Information about Bordeaux wine

Individual evidence

- ↑ [1] |

- ↑ a b c d e Philippe Bidalon: Bordeaux. Sous les crus, la crise . In: L'Express , May 17, 2007, pp. 84-90

- ^ A b Christian von Hiller: High prices put off the wine merchants . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , April 27, 2010, p. 21

- ↑ Manfred Klimek alias CaptainCork: Joy in aging. The miracle of wrinkles. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 23, 2015 ; accessed on March 8, 2018 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Christian von Hiller: LVMH joins Cheval Blanc . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , August 17, 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Christian von Hiller: Bordeaux wine is slipping even deeper into the crisis . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , April 19, 2006.