Buddenbrooks

1 = Mengstrasse No. 4: Buddenbrooks / Manns parent house, today a museum

2 = Fischergrube: Thomas' new house; Anna's flower shop

3 = town hall: citizenship; Senate

4 = Breite Strasse

5 = Beckergrube: theater; Club

6 = Trave

7 = Mühlenteich

8 = Wall

Buddenbrooks: Decay of a Family (1901) is the earliest of Thomas Mann's great worksand is today considered the first social novel in the German language of international renown. It tells of the gradual decline of a wealthy merchant family over four generations and illustrates the social role and self-perception of the Hanseatic upper middle class between 1835 and 1877. In 1929 Thomas Mann receivedthe Nobel Prize for Literature for Buddenbrooks .

Thomas Mann's own family history served as a template for the plot. The scene of the event is his hometown Lübeck . Without explicitly mentioning the name of the city, many minor characters are demonstrably literary portraits of Lübeck personalities of that time. Thomas Mann himself becomes part of the plot in the character of Hanno Buddenbrook .

History of origin and impact

Emergence

A volume of Mann's novellas was published by S. Fischer Verlag in 1898 under the title Der kleine Herr Friedemann . The publisher Samuel Fischer recognized the talent of the young author and in a letter dated May 29, 1897, encouraged him to write a novel: “But I would be pleased if you would give me the opportunity to publish a larger prose work of yours, maybe a novel, even if it's not that long. "

Buddenbrooks was written between October 1896 and July 18, 1900. Mann mentions the novel for the first time in a letter to a friend, Otto Grautoff , dated August 20, 1897. It was preceded by the end of May 1895, also in a letter to Grautoff, the Mention of a family novel in an autobiographical sketch. In his life outline (1930), Thomas Mann describes the beginning of the work during his stay in Palestrina . Over the next few years the novel grew to the size it is known today. On July 18, 1900, Thomas Mann completed the manuscript and sent it to Samuel Fischer on August 13, 1900. The publisher initially asked the author to cut the manuscript in half, but the author refused. The novel was therefore published unabridged.

The original manuscript was deposited with the Munich lawyer Valentin Heins after Thomas Mann emigrated and destroyed in a bomb attack in his office during the Second World War. Extensive preparatory work and notes are preserved, from which the genesis of the novel emerges.

Edition history

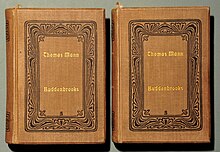

The work was published on February 26, 1901, in two volumes, with an edition of 1,000 copies. Sales were slow. The high price for the time of 12 marks (stapled) and 14 marks (bound, fig right) probably hampered sales. Only the one-volume second edition from 1903 with 2,000 copies, bound for 6 marks, stapled for 5 marks and with the cover design by Wilhelm Schulz , ushered in a series of new editions and brought success. In 1918, 100,000 copies had been sold. In 1924 an English language edition appeared in the United States, translated by Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter . After Thomas Mann had received the Nobel Prize for Literature for Buddenbrooks on November 12, 1929 , an edition of 1 million copies was published in December 1930 at a reduced price, the so-called popular edition for only 2.85 Reichsmarks.

With the appearance of inexpensive paperback editions after the Second World War, the total circulation increased significantly. By 1975 four million copies were sold in German. In 2002 a newly edited edition of Buddenbrooks with commentary volume appeared as part of Thomas Mann's “Great Commented Frankfurt Edition of Works”. In 2005, the TV film series Die Manns - A novel of the century by Heinrich Breloer, broadcast on the occasion of Thomas Mann's 50th anniversary of his death, sparked new interest in Buddenbrooks . The German editions of the novel reached a circulation of over nine million copies by 2010. By 2000 Buddenbrooks had been translated into 38 languages, most recently into Icelandic.

Reactions in Lübeck

In Lübeck, the novel was initially recorded as a key novel . There were two decryption lists circulating in the city, which a bookstore loaned to its customers. Many of the people who saw themselves portrayed were indignant. The author was compared to the scandal writer Fritz Oswald Bilse . Thomas Mann tried to counter the outrage with the essay Bilse und Ich (1906). There he defends the writer's right to use reality as a poetic model: “Don't always ask who is that supposed to be. [...] Don't always say, that's me, that's that one. It is only your expressions from the artist occasionally. Do not disturb his freedom with gossip and abuse. "

content

The novel is divided into eleven parts, each with a different number of chapters.

First part

On a Thursday in October 1835, Buddenbrooks asked their family members, acquaintances and business friends to come to their new house “for a very simple lunch”, according to upper-class custom for the late afternoon. The new home, as a building and property in equal measure, was recently acquired by the bankrupt Ratenkamp family for 100,000 Kurantmarks . The establishment of the representative house, located on Mengstrasse in Lübeck, dates back to 1682.

In the opening part, the reader is introduced to three generations of the Buddenbrook family: The energetic head of the family Johann Buddenbrook d. Ä. and his wife Antoinette; their son Johann Buddenbrook d. J. (called Jean) with his wife Elisabeth (Bethsy), plus their children, eight-year-old Antonie (Tony), nine-year-old Thomas and seven-year-old Christian. The guests are also part of the future novel staff.

Johann Buddenbrook the Elder Ä. is the owner of the grain wholesaler Buddenbrook, which he took over from his father, the company founder. His son Jean is an associate in the family business and is in no way inferior to his father's business acumen. Many times he had been "superior to him in resolutely seizing the advantage." But in contrast to his unsentimental father, he has a tendency towards pietistic piety. He is always anxious to be perceived “as a person with religious feelings”.

Meißner plates with gold rims and heavy silver cutlery are used for eating. The “very simple lunchtime bread” consists of herb soup along with toasted bread, fish, a colossal, brick-red, breaded ham with shallot sauce and such an amount of vegetables that everyone could have been satisfied from a single bowl . This is followed by plettenpudding , a layered mixture of macaroons, raspberries, biscuits and egg cream , to which golden yellow, grape-sweet old malvasia is served in small dessert wine glasses . Finally, the next girl applies butter, cheese and fruit.

In a contrasting parallel plot, the son of the head of the family from his first marriage, Gotthold Buddenbrook, who was not present and who was rejected years ago, is deprived of part of his inheritance. Senior and junior bosses coordinate after the guests have left. The pietistic and pious Jean advises his father to reject Gotthold's demand in good conscience so that the company's assets are not diminished.

Gotthold Buddenbrook had been cast out because of an improper marriage. In spite of the strict prohibition imposed by the head of the family, he had married a Mamsell Stüwing and thus married into a "shop" rather than a company. In the manageable trading town, however, a "precise" distinction was made between the "first and second districts, between the middle class and the lower middle class."

Second part

The Buddenbrooks keep a family chronicle, a thick gilt edged notebook , the records of which go back to the end of the 16th century. In it, on April 14, 1838, Jean Buddenbrook recorded the birth of his daughter Clara, his fourth child, cheerfully and in pious gratitude. Turning the page back he comes across the lines that concern his marriage. “That connection, if he’s honest, wasn’t what you call a love marriage. His father had patted him on the shoulder and drew his attention to the daughter of the rich Kroger, who donated a substantial dowry to the company, he had heartily agreed and from then on he had worshiped his wife as his trusted companion ... With the second marriage of his father was no different. "

The Hagenström family has established a foothold in the city. Mr. Hagenström is co-owner of the export company Strunck & Hagenström and married into a wealthy Jewish family from Frankfurt, which was received with astonishment in the first circles of the city. The Hagenströms soon competed with the Buddenbrooks, both in terms of business and local politics. The children of both families are already competing with each other. When Hagenström's son, little Hermann, demands a kiss from Tony on their way to school in exchange for his breakfast, she fends off him. His sister interferes and the girls get into a fight. "Since that event, the camaraderie was almost over."

In 1842 Madame Antoinette Buddenbrook, wife of Johann the Elder, dies after a short illness. Ä. After her death, the widower becomes more and more apathetic and eventually withdraws from the company. Jean Buddenbrook is now the sole owner of the traditional grain trading company founded in 1768. In March 1842, a few months after his wife passed away, Johann Buddenbrook the Elder also died. Ä. a gentle death. Despite the unfavorable provisions of the father's will for Gotthold Buddenbrook, to which Jean adheres, a tentative reconciliation begins between the half-brothers.

After Easter 1842, Thomas Buddenbrook, aged sixteen, joined the company as an apprentice. He works with devotion, imitating the quiet and tenacious industry of his father. The company, "this idolized term", has lost "significant funds" after the payment of inheritance claims and legacies. In a nocturnal conversation, Jean Buddenbrook explains to his wife that the family is “not that extremely rich”.

The high school student Christian Buddenbrook aroused his father's displeasure when it became known that the “fourteen-year-old toddler” with a bouquet for 1 Mark 8½ Schilling, a considerable sum, marched into the cloakroom of an actress at the municipal theater, a “Demoiselle Meyer-de la Grange ”. The young artist is the lover of a well-known bon vivant who is present when the young Christian makes his funny entrance, so that the incident quickly gets around in the narrow city.

For educational reasons, when Tony begins to show "a bad tendency towards pride and vanity" and to exchange love letters with a high school student, he has to go to a boarding school for girls . It is run by the hunchbacked, small Therese (Sesemi) Weichbrodt. Despite their “strict care”, Tony has “a happy youth” here with her two friends Armgard von Schilling and Gerda Arnoldsen.

third part

Tony Buddenbrook is 18 years old. The Hamburg merchant Bendix Grünlich asked Tony's parents for her hand. Tony is upset. “What does this person want from me -! What have I done to him -? ”And bursts into tears. The mother encourages her: “The connection you are presented with is exactly what you would call a good match, my dear Tony. [...] you have time to think about it. [...] But we have to consider that such an opportunity to make your fortune does not come up every day, and that this marriage is exactly what duty and destiny dictate to you. Yes, my child, I have to hold that against you. "

Tony's father talks to his mother after looking through Grünlich's business books and inquiring about him in Hamburg: “I can't help but urgently wish for this marriage, which would only benefit the family and the company! […] Then one more thing, Bethsy, and I cannot repeat that often enough: […] Business is quiet, oh, too quiet. [...] We have not made any progress since father was recalled. "

Greenish Tony persistently courted. Tony is depressed, loses her usual freshness and is emaciated. The father ordered a recreational stay on the Baltic Sea, in Travemünde, in the house of the pilot commander Schwarzkopf, who was well known to him. There she met his son, the medical student Morten, who came home during the semester break. They both fall in love. During a walk to the Mövenstein , Tony promises Morten not to listen to Grünlich and to wait for Morten's doctoral examination. Then he wants to ask her parents for her hand. In a letter Tony writes to her father, “You, the best father, I can tell that I am otherwise bound to someone who loves me and whom I love, that it cannot be told.” Shares their common life plan her father too.

The father writes back that Grünlich threatens suicide if he is turned away, and appeals to Tony's Christian duty. With regard to the traditional marriage decisions of the Buddenbrook family and company, he admonishes Tony: "You shouldn't have to be my daughter, not the granddaughter of your grandfather, who is resting in God, and not at all a worthy member of our family, if you seriously had in mind that you alone, to go your own messy paths with defiance and flutter. "

Informed by Tony's father, Grünlich comes to Travemünde, introduces himself to Morten's father as “Consul Buddenbrook's business friend”, pretends to be as good as engaged to Tony and invokes “older rights”. The staid pilot commander, who respects the class boundaries of his time, scolds his son. The mutual promise of Tony and Morten is over.

Tony submits to family reasons. One morning she proudly enters her engagement to Grünlich in the family chronicle, as she believes that she is serving the family with the engagement. Grünlich received a dowry of 80,000 marks from Jean Buddenbrook. At the beginning of 1846, Tony Buddenbrook married Bendix Grünlich, a businessman in Hamburg.

Thomas leaves for Amsterdam to expand his commercial knowledge. Before that, he says goodbye to his secret lover, the beautiful but poor flower seller Anna , and breaks up their mutual connection. He justified his decision to Anna by saying that he would one day take over the company and therefore have the duty to “play a game” and marry appropriately.

fourth part

On October 8, 1846, Tony gave birth to their daughter Erika. Grünlich bought a villa outside of Hamburg. A rental carriage is ordered for joint visits to Hamburg. He himself drives into town in the morning with “the little yellow car” and only comes back in the evening.

Jean Buddenbrook loses 80,000 marks in one fell swoop due to the bankruptcy of a business partner in Bremen . In Lübeck he has to "savor all the sudden cold, the reluctance, the mistrust that such a weakening of working capital in banks, friends and companies abroad tends to cause." On top of that, Grünlich has become insolvent. Jean Buddenbrook visits Tony in Hamburg and explains her husband's financial situation. Tony is willing to follow Grünlich into poverty out of a sense of duty. If this were done out of love, Jean ponders, he would have to protect his daughter and grandchild from this “catastrophe” and keep Grünlich “at all costs”. He now apologizes to Tony for urging her to marry Grünlich at the time, and assures her that he "sincerely regrets his actions at this hour." In tears, Tony admits that he never loved Grünlich. "He was always disgusting to me ... don't you know that?" In order not to withdraw any more money from the company, both agree that Tony will leave Grünlich and divorce him because of Grünlich's inability to care for his wife and child. “The word 'company' hit the mark. Most likely it was more decisive than even her dislike of Mr. Grünlich. "

In the presence of Grünlich's banker, the Mephistophelian-malicious Kesselmeyer, Jean Buddenbrook looks again at his son-in-law's books. He learns from Kesselmeyer that when he made earlier inquiries about Grünlich, of all people, he turned to his creditor. In order to secure their outstanding claims on Grünlich, they had glossed over his business situation. Grünlich's business books, about which Jean had praised his wife, were also forged. Now he sees the real numbers, scornfully authenticated by Kesselmeyer. It becomes clear that Grünlich married Tony only to receive her dowry and to improve his reputation in the business world. In a fit of anger, Grünlich also admits this.

The 1848 revolution took a very light course in Lübeck, which is described with some irony, not least because of the courageous intervention of Jean Buddenbrook. But his father-in-law Lebrecht Kröger dies of excitement about "the Canaille" in jeans arms.

In 1850, Jean's mother-in-law died and the Buddenbrook family received a considerable inheritance.

Christian Buddenbrook, who was to study and choose an academic career, had broken off this career and started as a commercial apprentice in a London trading company. In the meantime, his discontinuity has led him to Valparaíso in Chile. The Hagenströms, which compete with Buddenbrooks, are making further progress.

Jean Buddenbrook dies unexpectedly in 1855.

Part five

In 1855, at the age of 29, Thomas was the boss of the Buddenbrook company and head of the family. The capital amounts to 750,000 marks. Elisabeth, the widow of Jeans, is used as a universal heiress, which will later prove fatal. The long-time authorized signatory Friedrich Wilhelm Marcus becomes a partner at the will of the late Jean Buddenbrook and brings in equity of 120,000 marks. From now on he will participate in the profit according to this quota. The company's assets (excluding real estate) increase to 870,000 marks with Marcus' contribution. Still, Thomas is dissatisfied. Johann Buddenbrook had over 900,000 in his prime.

The young boss brings freshness and enterprising spirit to the company, even if he has to drag the skeptical Marcus behind him like "a lead ball". Thomas skillfully uses the effects of his personality in business negotiations. He enjoys great popularity and recognition everywhere: with the servants of the housekeeping in Mengstrasse, with the captains of his trading company, the managers in the warehouse clerks, the carters and the warehouse workers.

At his mother's request, Christian returned from overseas in 1856 after an eight-year absence - in a large-checked suit and with manners that imitate the English style. Thomas hires him as authorized signatory and successor to Mr. Marcus. In the office, Christian soon turns out to be a stroll. He makes no secret of his contempt for proper office work from Thomas. His actual talents come into their own in the men's club. There he is in demand with his “amusing, social talent” and provides entertainment for the people present with small improvised appearances.

After Jean Buddenbrook's death, his widow Elisabeth kept up the pious hustle and bustle in the house and intensified it. She holds prayer daily, opens a Sunday school for little girls in the back office rooms and organizes the weekly "Jerusalem Evening" for older women. Pastors and missionaries come and go, including Pastor Sievert Tiburtius from Riga , who will soon be asking for the hand of nineteen-year-old Clara, the youngest daughter of the family. Tony, who lives with her mother, cannot really get used to the pious goings-on.

Thomas is in Amsterdam on business for a long time. In a letter he announced that he had found his future wife there in Gerda Arnoldsen, the daughter of a wealthy business partner and Tony's former pension friend. After the end of the year of mourning, both Clara and Tiburtius and, at the beginning of 1857, Thomas and Gerda married in December 1856, with whom the Buddenbrook family received 100,000 thalers (300,000 marks) dowry.

While Thomas and Gerda go on a two-month honeymoon through Northern Italy, Tony furnishes the new and larger house that Thomas had previously acquired for the young couple. After his return, Tony confesses to her brother that she too would like to be married again to relieve the family and because she is bored with her pious mother's household. She even briefly considered accepting a position as a partner in England, even if it was actually "unworthy".

Sixth part

Thomas and Gerda Buddenbrook gave their first "lunch party". The dinner dragged on from five to eleven o'clock. At the stock exchange they talked about it “in the most praiseworthy terms” for eight days. "Truly, it had been shown that the young consul" knew how to represent. "

Tony returns from a long stay in Munich in a good mood. It was there that she met Alois Permaneder, the partner in a hops shop. Thomas suffers from Christian's embarrassing loquacity. Above all, he perceives his constant reports about signs of illness of all kinds (“I can no longer do it”) as uncontrolled, informal and ridiculous. The younger Buddenbrook is only called Krischan in town , and his clowning in the club is well known. But what bothers Thomas most is that Christian does not hide his love affair with Aline Puvogel, a simple extra from the summer theater, as the decency of the family dictates, but rather shows himself "with the one from Tivoli on an open, bright street".

After Christian had claimed in the club that “every businessman is a crook, actually and in the light of day”, a scandal breaks out between the brothers. In a private conversation, Thomas persuades his brother to leave the Buddenbrook company. With an advance on his future inheritance, Christian becomes a partner in a Hamburg trading company.

Tony is hoping for a marriage with the hop dealer Permaneder, her Munich acquaintance, a man of 40 years. Tony's comment: "This time it's not about a brilliant match, just about the fact that the notch from back then is roughly wiped out again by a second marriage." After an awkward decency visit by the mustached bachelor in the Buddenbrook house, the marriage actually takes place and Tony moves to Munich, where she can't really get used to. To her disappointment, Mr. Permaneder retires with the interest from Tony's dowry of 17,000 thalers (51,000 marks). A daughter dies shortly after giving birth. One night Tony surprises her husband when he is drunk and tries to kiss the struggling cook. Tony cuts him off and leaves him standing upright. Herr Permaneder casts a curse so monstrous that Tony cannot utter "the word" for a long time and stubbornly refuses to reveal it to Thomas. She takes the incident as an opportunity to divorce the "man without ambition, without striving, without goals". The “scandal” of a second divorce does not affect her. Thomas can't change her mind. Mr. Permaneder agrees to the divorce and returns Tony's dowry, an act of fairness he was not believed to be capable of.

Seventh part

Hanno, Thomas' and Gerda's son, was born in 1861. He was given the name Justus Johann Kaspar. The baptism will take place in Thomas Buddenbrook's house. One of the two godparents is the ruling mayor. The sponsorship was arranged by consul Thomas Buddenbrook and Tony Permaneder. “It's an event, a victory!” - The last well-wisher is the warehouse worker Grobleben, who cleans the boots of Thomas' family as part of a sideline. His improvised words turn unwillingly into a kind of funeral oration for the clumsy man. Thomas Buddenbrook steps in and helps Grobleben to have a mild exit.

Christian Buddenbrook is now 33 years old, but already looks significantly older. His hypochondriacal complaints seem delusional. In Hamburg, after the death of his business partner, against the advice of his brother, he continued to run the company in which he had entered as a partner as the sole owner and is now facing a financial disaster. Bethsy Buddenbrook, his mother, pays him a further advance of 5,000 thalers (15,000 marks) on his inheritance. This is how Christian can settle his debts and avoid bankruptcy. He plans to move to London soon and take a job there. With Aline Puvogel, the Tivoli extra, he now has an illegitimate daughter for whom he has to pay alimony ; Thomas, however, is of the opinion that the child was only foisted on Christian.

Thomas Buddenbrook is elected Senator in his hometown. He can only just outperform his competitor Hermann Hagenström, the Hermann Hagenström whom Tony refused to kiss when they were children. Hagenström is now one of the “five or six ruling families” in the city.

In 1863 the company flourished like in the times of Johann Buddenbrook the Elder. Ä. But Thomas feels "a decrease in his elasticity, a more rapid wear and tear." In the desire for "a radical change", "after the elimination of everything old and superfluous", Thomas had a new, magnificent house built.

Christian telegraphs from London and expresses his intention to marry Aline Puvogel, which his mother "strictly rejects".

Little Hanno, the future boss of Buddenbrook, is developing slowly. He only learns to walk and speak late.

An unfavorable business deal and a speech duel in urban affairs, in which he was defeated by Hermann Hagenström, gave Thomas Buddenbrook an inkling that he could not hold onto happiness and success in the long term. Resigned, he quotes a Turkish proverb: "When the house is finished, death comes."

Clara Buddenbrook, married Tiburtius, has died. In her last hours she had asked her mother in writing, with an uncertain hand, to pay off her future inheritance to her husband, Pastor Tiburtius. The pious mother ignores the head of the family, Thomas, and complies with the request, which is clearly Tiburtius behind. Thomas is dismayed when he learns that his mother has paid this "wretch" and "legacy sneak" 127,500 Kurantmarks. After all, Tiburtius had already received a dowry of 80,000 marks. The mother justifies herself, Christian and Tony also agreed. Thomas has confidence in the “ailing fool” Christian, who is currently lying in a Hamburg hospital with rheumatoid arthritis. But that Tony should also have agreed, he does not believe his mother: "Tony is a child" and would have told him.

Towards the end of the quarrel with his mother, Thomas confesses: "Business is going bad, it is desperate, exactly since the time that I spent more than a hundred thousand on my house." In 1866, the year of the Austro-Prussian War , Buddenbrooks lost 20,000 thalers (60,000 marks) due to the bankruptcy of a Frankfurt company.

Eighth part

Tony's daughter Erika, now 20 years old, married the director of a fire insurance branch in 1867, Hugo Weinschenk, who was almost forty, a self-confident, uneducated and socially clumsy man who earned an annual income of 12,000 Kurantmarks. Tony is allowed to move into the young couple's apartment in order to be able to help their daughter, who is still inexperienced in the household. Her daughter's marriage makes her overjoyed. "And Tony Buddenbrook's third marriage began."

Christian is back in town. Gerda Buddenbrook, the violin virtuoso, and Christian, who is interested in theater and tingling , get along well.

The nanny Ida Jungmann tells Tony about Hanno's sensitive nature and poor health. He doesn't like going to school, has nightmares and recites poems from Des Knaben Wunderhorn in his sleep . The old family doctor Dr. Grabow also had no real advice and was satisfied with the diagnosis of pavor nocturnus .

At forty-two, Thomas Buddenbrook feels like a "weary man". But he can maintain his facade with a lot of self-discipline. “The elegance of his exterior stayed the same.”

With Tony's mediation - contrary to the principles of the Buddenbrook merchants - Thomas entered into a considerable speculative deal: In the spring of 1868 he bought the money-troubled owner of the Mecklenburg estate Pöppenrade for half the price of his entire annual harvest of grain still " on the stalk ".

A few months later, on July 7th, 1868, the hundredth anniversary of the founding day (1768) of the Buddenbrook company is celebrated. During the celebration, Thomas Buddenbrook received a telegram with the message that a hailstorm had destroyed the “Pöppenrader harvest”.

Gerda Buddenbrook is friends with the organist Pfühl. They argue about Wagner's music . On Monday afternoons, Mr. Pfühl gives little Hanno music and piano lessons. In contrast to school, where it is difficult for him to concentrate, Hanno shows an effortless conception here, "because you only confirmed what he had actually known from time immemorial." On his eighth birthday, Hanno plays from his mother Accompanied by the violin, the assembled family has a little imagination of their own. Aunt Tony embraces him and shouts: "He's going to be a Mozart, " but she didn't understand the slightest thing about the music being played. When Thomas complains to Gerda that music alienates him from his son, Gerda accuses him of lacking the necessary understanding of the art of music.

Hanno is close friends with Kai Graf Mölln, who is the same age. One day alone in the living room, Hanno flips through the family chronicle and reads “the whole genealogical swarm.” Following an intuition , he draws a double line under his name with a ruler. To his father, who confronts him, he replies: "I believed ... I believed ... nothing more would come!"

Weinschenk, Tony's daughter's husband, has repeatedly damaged other insurance companies with fraudulent reinsurance . Tony is horrified to find out, especially when it turns out that Moritz Hagenström, Hermann Hagenström's brother, is the public prosecutor at the trial. She accuses him of particularly harsh persecution of the case and cannot understand that "one of us" (ie from a respected family) can be put in prison. Weinschenk is sentenced to three and a half years in prison.

Part ninth

In autumn 1871 Elisabeth ("Bethsy") Buddenbrook, the former world lady, who had filled her last years with piety and charity, died of pneumonia after a long sick bed and a tough agony . The female servants immediately carry laundry baskets full of clothes and linen from the house, things that the dead woman supposedly promised them. Then the family members divide the household effects of the deceased among themselves.

To the amazement of his siblings, the bachelor Christian claims a large part of the laundry and dishes for himself, because he wants to marry his daughter's mother, Aline Puvogel, an extra from Tivoli. His mother had denied him this all his life. Now Thomas, the new head of the family, denies him. Pale and trembling with anger, he accuses Christian of being no longer his own master. The day the will is opened will show him that he cannot ruin his mother's inheritance: “I will manage the rest of your assets and you will never get your hands on more than a month's allowance.” Christian also wants the two children, Aline Puvogel had born before their daughter, adopt and legitimize his own child. Thomas Buddenbrook: “So that after your death your property would pass to those people?” “Yes,” replied Christian, “that's how it should be.” Thomas forbids him to do that too. This time, however, Christian offers strong resistance, and it comes to pass a bitter argument, as a result of which Thomas threatens: "You won't do it [...] I'll have you declared childish, I'll have you locked up, I'll destroy you."

The house on Mengstrasse was sold for 87,000 marks at the beginning of 1872, to Hermann Hagenström of all people , to Tony's embarrassment . Christian rents a modest three-room apartment for himself and his family, "a Garçon apartment" near the club. Tony moves with his daughter Erika and granddaughter Elisabeth into a bright and “not without claim to refinement furnished floor on Lindenplatze. It was a pretty little apartment and on the front door a blank copper sign read in delicate writing: A. Permaneder-Buddenbrook, widow. "

Part tenth

The 46-year-old Thomas Buddenbrook feels “unspeakably tired and disgruntled”. He plays hollowed out in his elegant wardrobe and with his obliging demeanor like an actor himself. At the stock exchange, so is mocked behind his back, he looks “only decorative”. If he includes the property, his fortune amounts to 600,000 marks.

From Hanno , who is now eleven years old, Thomas is hoping for a "capable and weatherproof" successor. He lets him do gymnastics, skate and swim. In the port he shows him the fire fighting work on the company's own ships. He also takes Hanno with him on social visits to houses to which he has a business obligation. But the son sees through the father's social versatility and realizes the effort this self-portrayal takes.

Hanno is often with his friend Kai. He tells him mysterious stories, the strangest moments of which Hanno accompanies with sweet chord progressions on the harmonium . Hanno usually spends the summer holidays at the sea, away from all the adversities of school. Then he is quite happy in peaceful and sorrowless seclusion.

In 1873 Hugo Weinschenk, Tony's son-in-law, was released early from prison. Since he is no longer socially acceptable in the city, Tony and her daughter secretly expect the separation. After a few days Weinschenk travels to London. He only wants to take his wife Erika and their daughter in when he can offer them a decent life again. From then on his track is lost. Tony posts a search ad a number of times to facilitate her daughter's divorce suit for malicious abandonment.

Gerda Buddenbrook, it is believed in the city, and her husband also fears that, has a relationship with Lieutenant René Maria von Trotha. He visits Buddenbrooks' and makes music with Gerda in the salon, locked away from the other residents and domestic staff. For Thomas Buddenbrook, the pauses in which the music is silent for "so long, long" become painful. But he doesn't dare to confront Gerda with her “nervous coldness in which she lived and which she exuded”. When Hanno and his father meet at the door of the salon, in which Gerda and the lieutenant have been staying for hours, and the music is silent again for a long time, the other strangeness between them is lifted for a few seconds. The sensitive Hanno understands his father's secret jealousy.

Thomas Buddenbrook is 48 years old. His bad physical condition and depressed mood give rise to a premonition of death. “Half sought, half by accident” comes Schopenhauer's main work, “ The world as will and imagination ”. The chapter “About death and its relationship to the indestructibility of our being” reveals to him “an eternal distant view of light.” Death now appears to him as “the return from an unspeakably embarrassing mistake”. Thomas Buddenbrook draws up his will.

In September 1874, on medical advice, Thomas went to the Baltic Sea to relax for a few weeks. Christian joins him of his own free will. There is a tacit reconciliation between the brothers. The monotony of the sea, the mystical and paralyzing fatalism with which the waves roll in, trigger a deep need for calm in Thomas.

Four months later, Thomas has to seek help from dentist Brecht. The tooth extraction failed without anesthesia. On the way home, Thomas faints, falls, and hits the pavement with his face. After a short period of sickness, he dies without having regained himself. Anna, his childhood sweetheart, is let into the drawing room where he is laid out at her request. In a four-horse hearse, followed by a long line of carriages and wagons, Senator Buddenbrook is driven to the cemetery in solemn pomp and buried in the family grave.

Eleventh part

Hanno was not designated as a company heir by his father. The company and property are to be sold within a year by Kistenmaker, the executor and former schoolmate of Thomas. On the paper Thomas had given a fortune of 650,000 marks as a legacy. After a year it turns out that "this sum was not even remotely to be expected". Kistenmaker has no luck with the liquidation of the estate. Word of the losses got around: Several craftsmen and suppliers are pushing Gerda to pay their bills quickly because they fear that they will no longer receive their money.

Christian, whose maternal inheritance is also managed by Kistenmaker, marries Aline Puvogel after the death of his mother and brother, whose veto is no longer an obstacle. Tony writes Aline Puvogel "with carefully poisoned words" that she will never recognize her or her children as relatives. Because of his delusional ideas and obsessions , Aline allows Christian to be admitted to a psychiatric institution against his will and can thus continue her independent life “regardless of the practical and idealistic advantages that she owed to the marriage”.

Gerda Buddenbrook lets Kistenmaker sell the large house that Thomas had built at a loss because she can no longer finance the maintenance, and instead purchases a small villa in front of the castle gate in autumn 1876. She dismisses the long-serving nanny Ida Jungmann, who has never had a particularly good relationship with her and has recently exceeded her authority more often.

When Hanno, now sixteen , is allowed to accompany his mother to the Lohengrin opera , he feels intoxicated by the music. But sorrowful school lessons followed the next day. Hanno's lack of participation in the classroom and an unfortunate accident that is interpreted as a failure at school lead to the teachers' final decision not to move him to the next class. Depressed, Hanno no longer sees a future for himself, not even as a musician: “I can hardly do anything, I can only fantasize a little [...] I can't want anything. I don't even want to get famous. I'm afraid of it, exactly as if there was an injustice involved. "

In the spring of 1877 Hanno died of typhus . In his feverish daze, he closes himself off to the “voice of life”. His lack of will to live allows him to take refuge "on the path that opened up for him to escape." In the winter of the same year, Gerda Buddenbrook said goodbye to Lübeck and returned to her father in Amsterdam.

The theological - eschatological discussion about the existence of a life after death, which Tony Buddenbrook dubiously initiates at the end of the novel and poses the theodicy question, closes the circle to the first scene of the novel, where Tony Buddenbrook, as a little girl, the traditional Christian theology of creation ("I believe that God created me and all creatures") naively recites. The author relates the beginning and end of the world to the rise and fall of Buddenbrooks. The meaningfulness and justice of the world postulated by Sesemi Weichbrodt in conclusion seems to be questioned by the author in a slightly ironic way.

To style

Assembly technology

Thomas Mann saw himself as a naturalistic writer. Using the assembly technique that is characteristic of him , he incorporated foreign material such as occurrences of existing people, events of contemporary history, documents and lexicon articles into the novel. This gave the literary text authenticity. Citizens of Lübeck and relatives of Thomas Mann could recognize themselves in Buddenbrooks .

Leitmotiv and irony

Characteristic of Thomas Mann is his permanent play with leitmotifs .

- “The motif, the self-quotation, the symbolic formula, the literal and meaningful back-to-back relationship over long stretches - these were epic means in my opinion, enchanting for me as such; and early on I knew that Wagner's works had a more stimulating effect on my young artistic instinct than anything else in the world. [...] It is really not difficult to feel a touch of the spirit of the Nibelungenring in my ´Buddenbrooks´, this epic generation, linked and interwoven with leitmotifs . "

Almost all characters in a novel are assigned typical attributes, gestures or expressions. On the one hand, this technique helps the reader to remember. On the other hand, such formulas, once their symbolism has been recognized, can be interpreted in advance, or earlier moods hinted at again. In this way they clarify overarching relationships and create a system of relationships within the plant. But above all, they help ironize the stereotypical behavior of certain characters. Tony Buddenbrook, for example, quotes a comment by medical student Morten Schwarzkopf whenever she talks about honey as a “natural product”. The reminiscent repetition shows that after two unhappy marriages and divorces she has still not forgotten her unfulfilled childhood love, and at the same time ironizes her unshakable belief in Morten's scientific competence and her pride in her naively reproduced knowledge.

The novel owes its worldwide success not least to this benevolent irony . It amounts to a distanced acceptance - and thus ultimately to objectivity, because it always implies the downside of what is said. Such ambiguity is a consistent stylistic device in Thomas Mann's oeuvre.

Sometimes Thomas Mann's irony only shows itself in retrospect: A standing phrase Sesemi Weichbrodt, the head of a girls' boarding school, is the words she utters at birth celebrations, weddings or similar occasions: "Be happy, you good kend." On the forhead. As it turns out in the further course of the plot, the addressees thus encouraged become regularly unhappy.

Linguistic polyphony

The young author's artistic daring (Thomas Mann completed the novel at the age of 25) allows him to masterfully interweave languages , dialects , dialects , jargons and other linguistic peculiarities.

“Je, den Düwel ook, c'est la question, ma très chère demoiselle!” This is the second sentence of the novel, a mixture of Low German dialect and French phraseology. It introduces the "linguistic orchestration".

When it comes to foreign languages, French, English and Italian have their say. In addition to her Prussian dialect, the Buddenbrook family's nanny, Ida Jungmann, contributes a little Polish (in Thomas Mann's peculiar and inconsistent German spelling). Latin bring the blessing on the portal "Dominus providebit" as well as the school Ovid reading Hannos under the dreaded Dr. Coat bag .

In addition to High German, Thomas Mann also mastered the native dialect of the Lübeckers, the local Low German , a language that had been the " lingua franca " of the Hanseatic League in the Middle Ages and was not only spoken by ordinary people in the 19th century. But Baltic, West Prussian, Silesian, Swabian and Bavarian language peculiarities are also included. In addition, there is the individual diction of the characters in the novel, e.g. B. Christian Buddenbrook's hypochondriacal phrase: "I can no longer do it". The language palette also includes the professional jargon used by Hanno's teachers.

Characters of the novel

Basically, what Thomas Mann himself said about his figure drawing applies: The peculiarities and character traits of real people were used by him in a recognizable way, but poetically edited, combined and transformed in such a way that any direct inference from a novel character to a historical model is forbidden.

Johann Buddenbrook the Elder

Johann Buddenbrook the Elder (1765–1842) laid the foundation of Buddenbrook's fortune as a grain wholesaler and Prussian army supplier during the Wars of Liberation . His first wife Josephine, "the daughter of a Bremen merchant", whom he must have loved "in a touching way" and to whom he owes the most beautiful year of his life ("L'année la plus heureuse de ma vie"), died in childbirth his son Gotthold (1796). He never forgave the son for this “mother's murder”. In his second marriage, Johann Buddenbrook is "married to Antoinette Duchamps, the child of a rich and well-respected Hamburg family". Both live "respectfully and attentively [...] next to each other" and have a daughter and a son, Johann (Jean) Buddenbrook, who, although not the first-born, inherits the company after his half-brother Gotthold inflamed in passionate love for a certain "Mamsell Stüwing "Was and with her, despite the father's" strict prohibition, entered into [a] mesalliance ".

Johann Buddenbrook is sober objectivity and unshakable self-confidence, down-to-earth and cosmopolitan at the same time - he speaks both Low German and fluent French, in anger occasionally likes to do both at the same time. In addition, he can (accompanied by his daughter-in-law “on the harmonium”) “blow the flute”, a talent that he has not passed on. In his worldview he tends towards the philosophy of the Enlightenment and keeps a mocking distance from religion. However, he also values classical education and doesn't think much of the fact that the younger generation only has mines and money-making in mind, on the other hand, he doesn't like the ideals of romanticism with their love of nature: when his son Jean went against the plan the father refuses to have the overgrown garden tidied up because he prefers the great outdoors, Johann is amused.

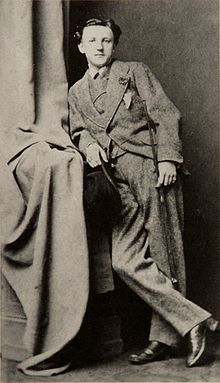

Johann Siegmund Mann I, the founder of the Mann company, is seen as a literary model in Thomas Mann's family (see fig.). The motto of the merchants in the novel comes from him: "My son, enjoy going to the shops during the day, but only do things so that we can sleep peacefully at night". He was 87 years old and, according to Viktor Mann , died "in the March of the Revolution of 1848, as it is said, of a stroke that brought him, the Lübeck bourgeois and republican, his boiling anger over the harmlessly rampaging ' Canaille '".

Consul Johann (Jean) Buddenbrook (approx. 1800–1855)

Johann (Jean) Buddenbrook (approx. 1800–1855) is the son of the second marriage between Johann Buddenbrook the Elder and Antoinette Duchamps. Jean Buddenbrook has "his father's deep-set, blue, observant eyes", but their expression is more dreamy. After the death of old Buddenbrook, he successfully continued the business of the company, as it turns out after his death, although he had "complained constantly in the merchant style". Jean Buddenbrook is the Royal Dutch Consul. In contrast to his father, Jean falls into a religious crush. Nevertheless he is an authority in the city, and his business acumen is not affected by his religiosity.

Consul Johann Siegmund Mann jun. (1797–1863) served as a template for Jean Buddenbrook. He was the actual chronicler of the Mann family, copied the chronicle booklet inherited from his grandfather, the oldest man, in the hereditary "Bible" and added sketches from the life of Johann Siegmund Mann senior. Johann Siegmund Mann also lost his first wife when his son was born and put the business in the hands of his son from his second marriage.

Johann Siegmund Mann jun. was elected "successive" to various offices in his hometown and would probably have brought even more political success if a competitor, Johann Fehling, had not harmed him. The first drafts of the novel's Hagenström family were still called Fehling, while Johann Fehling's children were really called Julchen and Hermann.

Senator Thomas Buddenbrook (1826–1875)

Thomas Buddenbrook, whose father, grandfather and great-grandfather had already worked in the city, “was the bearer of a hundred years of civil fame. The light, tasteful and compellingly amiable way in which he represented and exploited it was probably the most important thing. "

In the city there were rumors: “A little pretentious, this Thomas Buddenbrook, a little… different: different from his ancestors. It was known, especially the draper Benthien, that he not only got all of his fine and new-fangled clothes - and he owned an unusually large number of them: pardessus , skirts , hats, vests, trousers and ties - and that he also obtained his underwear from Hamburg. It was even known that he changed his shirt every day, sometimes twice a day, and that he changed his handkerchief and the Napoleon III. undressed perfumed mustache. And he did all this not for the sake of the company and the representation - the house 'Johann Buddenbrook' did not need that - but out of a personal inclination for the super-fine and aristocratic. "

Thomas Mann gave the young company boss Thomas Buddenbrook features of the dandy .

Tony (Antonie) Buddenbrook, divorced Grünlich, divorced Permaneder (born 1827)

Antonie Buddenbrook called Tony, is the first daughter of Jean and Elisabeth Buddenbrook, sister of Thomas, Christian and Clara, the mother Erika Weinschenks (née Grünlich) and grandmother Elisabeth Weinschenks.

Antonie Buddenbrook remains herself for life: childishly naive and unshakable in her sense of family. As a child, she is deeply impressed by the luxurious lifestyle of her grandparents, which dwarfs that of her parents. Noble becomes one of her favorite words and she has a fondness for satin ribbons that adorned the bedspread in her grandparents' house. In Lübeck adults say hello to little Tony, the child from the Buddenbrook family. "She walked around town like a little queen." Tony is very fond of being part of a respectable family. Despite the obvious family decline and despite her own life, which with two divorces doesn't exactly add to the fame of the family, she is still filled with pride in her origins, only the nobility appears to her even more noble. She likes to explain setbacks with the intrigues of others. B. the hated family Hagenström. When Gerda Buddenbrook says goodbye at the end of the novel to return to Amsterdam, Tony takes over from her the "family papers" with notes on the history of the Buddenbrooks, which were previously kept and continued by the head of the family.

It says about 47-year-old Tony: “Everything, every happiness and every sorrow, she had uttered in a flood of banal and childishly important words that completely satisfied her need for communication. [...] Nothing unspoken ate her; no silent experience bothered her. And that's why she had nothing to do with her past. ”At the same time, despite all the pathos, Tony also understands how to adapt to a new situation with resistance and to maintain her demands despite all the failures: As a divorced woman, she meets the social disregard as a divorced woman with the greater arrogance and Even your last, small apartment will be furnished “elegantly” as best you can.

His aunt Elisabeth Amalie Hyppolita Mann , divorced Elfeld, divorced Haag (1838–1927), served Thomas Mann as a template for Tony Buddenbrook. At Thomas' request, his sister Julia Mann wrote an extensive report about Aunt Elisabeth in 1897. Many details from this description have been taken over literally in the novel (the children's pranks, the "penchant for luxury", the anecdote with the bacon soup), although Julia had asked her brother for discretion, as the people involved were still alive. Like her literary image, Elisabeth Mann was married twice. Her parents also pushed her into her first marriage, and her husband went bankrupt. Elisabeth Mann was initially - according to Viktor Mann - "indignant" about the novel's indiscretion, but then met her fate "with humor and finally with pride" after she was only called Tony in the family.

The novel begins with the words of little Tony who recites from the catechism. She is also present in the final scene - but the very old Therese Weichbrodt has the last word. Tony becomes a contemporary witness for four generations of the Buddenbrook family, but always remains completely present. Even so, Tony isn't the novel's secret heroine. It neither grows nor changes. Even when she later, apparently resignedly, describes herself as an “ugly old woman”, it sounds from her mouth as if a child in disguise was speaking his role in the theater. Tony is the parody of an absolute principle that is relieved of time and the change of things: it is the comical incarnation of Schopenhauer's idea of the species, which gives the individual a kind of immortality in this world and makes him exclaim in all innocence: “Despite time, death and we are still all together! "

Christian Buddenbrook (born 1828)

Christian Buddenbrook (born 1828, the second son of Jean and Elisabeth Buddenbrook and brother of Thomas, Tony and Clara) is the opposite of his older brother Thomas.

When the 28-year-old Christian returned from a multi-year stay abroad, Thomas Mann describes him as follows: “Christian was by no means beautified. He was thin and pale. The skin stretched tightly around his skull everywhere, the large, humped nose protruded sharply and fleshless from between the cheekbones, and the hair on the head was already noticeably thinned. His neck was thin and too long and his skinny legs showed a strong curve outward. "

In contrast to Thomas, Christian does not value social conventions. He's also lacking in diligence and a sense of duty, he keeps rushing enthusiastically into new ventures and professional plans, but after a short time his motivation drops, so that his plans fail: first he wants to study, then he works for his brother in the office, after all, has his own company, takes over an agency for champagne, learns Chinese and "revises" a German-English dictionary - but he doesn't finish any of it, he gives up as soon as the allure of the new has faded or discipline is necessary. Christian is very talented in imitating and caricaturing other personalities, which regularly triggers outbursts of amusement. Christian already had this ability as a child. Already in the first chapter he imitates his teacher, the bizarre Marcellus Stengel, so exactly that the guests at the inauguration ceremony are very amused. Christian can also tell stories “with verve and color”. However, he is sometimes well aware that he has not achieved much in his life by bourgeois standards: When his nephew Hanno was given a puppet theater for Christmas, Christian was completely fascinated by it, but nevertheless admonished his nephew with a touch of seriousness not spending too much time on such things. He, Christian, did this - and therefore nothing was right with him.

Christian becomes a bon vivant and spends his free time with like-minded people in the club or theater, socializing in artistic circles and with women who are not befitting their class. In the whole city he is only known as Krischan and laughs at his jokes, nobody takes him seriously. Annoying family his penchant for is hypochondria and the description of his Zönästhesien . Christian also shows little sense of loyalty and does not pay attention to the consequences that his lifestyle could have on the reputation of the family and the Buddenbrook company. Once in the club he made the remark that actually every businessman is a fraud - and reacts with incomprehension when his angry brother explains to him that such statements (which, to make matters worse, were made in the presence of the worst competitor Hermann Hagenström) to him Damage the company's reputation.

Christian rejects his brother Thomas: "As long as I can remember, you have let such a cold flow on me that I have constantly frozen in your presence".

After his brother's death, no one prevents Christian from marrying Aline Puvogel, his long-time lover (he is convinced that he is the father of their illegitimate daughter Gisela). However, soon after the marriage, Aline can persuade a doctor to admit Christian permanently to a mental hospital because of his delusions.

Friedrich Wilhelm Lebrecht Mann , called "Uncle Friedel" in the family, is a role model for Christian Buddenbrook. Klaus Mann reported that Uncle Friedel was "a neurotic do-it-all" who "hung around the world and complained about imaginary diseases". On October 28, 1913, Friedrich Mann protested against what he believed to be a deplorable depiction in the novel in a much laughed at advertisement in the "Lübecker Generalanzeiger":

- “If the author of 'Buddenbrooks' pulls his closest relatives in the mud in a caricatural way and blatantly reveals their life stories, every right-thinking person will find that this is reprehensible. A sad bird that pollutes its own nest! Friedrich Mann, Hamburg. "

Christian Buddenbrook doesn't just have quirky uncle traits. The discrepancy between the unequal brothers Christian and Thomas already reflects the beginning of the conflict that later broke out between Thomas Mann and his brother and writer rival Heinrich Mann . Christian's way of life is similar to that of young Heinrich Mann.

In the fictional world of the novel, Thomas recognizes his own features in Christian's personality, which he suppresses in himself. In an argument, Thomas Buddenbrook accuses his brother: “I have become what I am,” he said at last, and his voice sounded moved, “because I didn't want to be like you. If I avoided you inside, it happened because I have to watch out for you because your being and essence is a danger to me ... I speak the truth. ”But Christian embodies an existential threat not only for Thomas Buddenbrook, also for his author. Because if he is also "not an artist, he is the beginning of all the moral worries that Thomas Mann had in his life about being an artist."

Gerda Buddenbrook b. Arnoldsen (born 1829)

Gerda lives in Amsterdam with her widowed father. As a young girl, she lived in Lübeck for some time, in the same boarding school for girls as Tony. At that time the girls joked that Gerda could marry one of Tony's brothers. Gerda's sister is already married. Her father is considered "the great businessman and almost an even greater violin virtuoso". Gerda also makes music and is a gifted violinist. She owns a precious Stradivarius . Her receptivity to contemporary music made her an admirer of Wagner .

Thomas Buddenbrook wins Gerda at the height of his career. Until then she had “firmly upheld her decision never to marry.” Thomas was impressed by her musicality, even if music is alien to him. He writes to his mother: “This one or none, now or never!” In addition, Gerda is a brilliant group whose dowry brings fresh capital into the company.

Her beauty makes an impression in Lübeck: lush and tall, with heavy, dark red hair, the brown eyes lying close together surrounded by bluish shadows. The face is “matt white and a little haughty.” In contrast to the pallor and the shadowy eyes, her smile shows white, strong teeth. The enigmatic aura that surrounds them prompts the broker and art lover Gosch to call them " Her [a] and Aphrodite , Brünhilde and Melusine in one person". She fulfills her duties as Senator Buddenbrook without being absorbed in them.

Gerda's musicality contrasts with everyday life in the Buddenbrook family, which is determined by practical issues. While her husband is working on his desk in the basement for the company, he hears her playing music with Lieutenant von Trotha above her in the music room. Thomas Buddenbrook has to painfully recognize a kinship here that he is denied. In terms of motif, Gerda Buddenbrook embodies the music in the novel as a detached and destructive element that stands in the way of fresh energy and business diligence and at the same time is above life's toil and duty. Her son Hanno, the last Buddenbrook, inherited her musicality and cosmopolitanism. Ageless and unchanged from time to time, she left Lübeck after the death of husband Thomas and son Hanno and returned to her hometown of Amsterdam, as if her mission had come true.

Gerda Buddenbrook shows parallels to Thomas Mann's mother Julia Mann . They both grow up motherless and spend a few years in a Lübeck girls' boarding school. Julia Mann also leaves the narrow hometown with her class arrogance after the death of her husband . Gerda Arnoldsen reminds more of Gerda von Rinnlingen in the novella Der kleine Herr Friedemann, however, than of Julia Mann . There she brought death to the title hero.

Hanno (Justus Johann Kaspar) Buddenbrook (1861–1877)

Hanno is the only child of Thomas and Gerda Buddenbrook.

“With his long, brown eyelashes and golden brown eyes, Johann Buddenbrook always stood out a little strange among the light-blonde and steel-blue-eyed Scandinavian types of his comrades in the schoolyard and on the street, despite his Copenhagen sailor suit. [...] and still lay, as with his mother, the bluish shadows in the corner of his eyes - these eyes, which, especially when they were turned sideways, looked at them with an expression as timid as they were negative, while his mouth was still closed kept closed in that wistful way. "

Little Johann embodies the fourth generation of Buddenbrook, apart from the ancestors who are only mentioned in the novel. Hanno's health is always at risk. Even as a toddler, its development is delayed. Comparatively harmless childhood illnesses almost lead to death for him. He later has significant problems with his teeth. Hanno is also not mentally robust: He suffers from nightmares and is overly fearful. He finds contact with other children difficult. When pressured, he begins to cry and stutter. His upbringing exacerbates these problems. For example, Ida Jungmann keeps him away from other children, and his father gives him information about the city or the Buddenbrook company without realizing that this makes Hanno even more fearful and discouraged.

In his nature, Hanno has no disposition to be a businessman, nor is he suitable for a position in public because of his shyness and fear of people. When he was already showing his own little fantasy on the piano at the age of eight, he was trusted to become a musician. But you have to give up hope when, despite piano lessons, he cannot play a Mozart sonata flawlessly from the sight, but "just fantasizes a little". His achievements at school leave a lot to be desired, and he is not transferred several times. He suffers from the sometimes quite incompetent and brutal teachers, but also from the teasing of his classmates. Due to a lack of discipline, Hanno does not make it very far, even in subjects in which only memorization is important or the teacher is well disposed towards him; instead of doing his homework, he prefers to fantasize on the piano. He hardly has any friends with his schoolmates, the only friend is Kai Graf Mölln, who is also an outsider due to his origins and the poverty of his father as well as his literary interests. People outside the family see Hanno as an outright failure, even his guardian Kistenmaker tells the pastor that Hanno comes from a rotten family and he must be given up. Hanno himself also sees clearly that he lacks the will to perform, that nothing can come of him, and accepts his fate.

Antoinette Buddenbrook b. Duchamps († 1842)

Antoinette Buddenbrook is the second wife of Johann Buddenbrook the Elder. The wedding with her was by no means a love marriage, but as the daughter of a rich Hamburg merchant, she is a good match. She becomes the mother of Jean Buddenbrook. In 1842 she died after an illness lasting several weeks; her husband is deeply affected, because even if he never loved her as much as his first wife, she stood by his side wisely and dutifully for many years. The fate of Catharina Mann, née Grotjahn, the wife of Johann Siegmund Mann the Elder, served as a template.

Bethsy (Elisabeth) Buddenbrook b. Kroger (1803–1871)

Elisabeth is the wife of Consul Jean (Johann) Buddenbrook and the mother of Thomas, Christian, Tony (Antonie) and Clara. She is initially described as an elegant and cosmopolitan woman who fulfills her role as consul's wife very well:

"Like all Krögers, she was an extremely elegant figure, and if she could not be called a beauty, she gave the whole world a feeling of clarity and trust with her bright and level-headed voice, her calm, safe and gentle movements."

After her husband's death, she adopts his pietistic piety, which, however, escalates into piety, and, like her deceased husband, receives constant visits from pastors and missionaries, to whom she slips donations. Behind the back of her son and head of the family Thomas Buddenbrook, in 1864, when her daughter Clara was dying, she transferred 127,500 Kurantmark to her husband, Pastor Tiburtius, and thus permanently weakened the company's cash assets (see Section 2.7). Even in old age she tries to maintain her former elegance: She continues to wear silk clothes and finally a wig after her hair has turned gray despite a “Parisian tincture”.

Elisabeth Mann, née Marty (1811–1890), wife of the consul Siegmund Mann the Younger, served as a model.

Clara Tiburtius b. Buddenbrook (1838–1864)

Clara is the fourth child of Jean and Elisabeth Buddenbrook. When her father dies, she is still a minor, so Justus Kröger is appointed her guardian. Clara Buddenbrook is described as serious and strict, she shares her father's religious inclinations and finally takes his role as a reader during domestic devotions. In 1856 she married Pastor Tiburtius, who frequented the Buddenbrooks' house, and moved with him to Riga.

“As for Clara Buddenbrook, she was now in her nineteenth year [when she married Tiburtius] and was, with her dark, straight-parted hair, her stern yet dreamy brown eyes, her slightly curved nose, her mouth a little too tightly closed and her tall, slender figure has grown into a young lady of austere and peculiar beauty. […] You had a somewhat imperious tone in dealings with the servants, yes, also with your siblings and your mother, and your alto voice, which only knew how to lower itself with certainty, but never to raise it questioningly, had a commanding character and could often take on a short, hard, intolerant and exuberant timbre. "

Olga Mann, married Sievers (1846–1880), served as the model for the character in the novel, and her husband, the businessman Gustav Sievers, as model for Tiburtius.

Gotthold Buddenbrook (1796-1856)

Gotthold Buddenbrook is the unloved son of Johann Buddenbrook the Elder. Ä. from first marriage. The first wife, Johann Buddenbrooks, died when Gotthold was born. Gotthold was rejected and settled with a small portion of the inheritance because of an idiosyncratic, improper marriage (see above content, first part). Instead of Gotthold, the first-born, his half-brother Jean - from Johann's second marriage - becomes the head of the Buddenbrook company. Gotthold is described as stout and short-legged. After the death of Johann Buddenbrook the Elder Ä. Gotthold asks his half-brother Jean whether the provisions of his father's will have been changed. Although they remain in force and Jean Gotthold does not give a larger portion of the inheritance, the brothers are timidly reconciled - Gotthold realizes that Jean cannot afford to give him a larger share of his father's fortune. After Jean's death, Thomas Buddenbrook voluntarily left the prestigious office of Dutch consul to his uncle as a gesture of reconciliation. Unlike Gotthold, his wife and three daughters still have an aversion to the wealthier relatives in Mengstrasse. Gotthold himself also has little business ambition - after receiving his small share of his father's inheritance, he gives up his “shop” and retires.

Gotthold's daughters Friederike, Henriette and Pfiffi Buddenbrook remain unmarried because they have no dowry. They comment on the setbacks of the Buddenbrook family with glee. For example, after Hanno's birth - instead of rejoicing with the family - they point out with envy and malice that Hanno's weak appearance and delayed development. Even in praise they know how to hide sharp remarks. When their mother dies, they behave as if the constant rejection of their rich relatives had brought them to the grave - in reality, she has become “very old”. Consul Siegmund Mann served as a template for Gotthold Buddenbrook; Luise, Auguste and Emmy Mann are identified as role models for Pfiffi (= Josefine), Henriette and Friederike Buddenbrook. Thomas Mann had previously used the names for the three sisters of the protagonist in his story Der kleine Herr Friedemann .

Klothilde Buddenbrook

Klothilde Buddenbrook is the daughter of a poor relative, Bernhardt Buddenbrook (a nephew of Johann Buddenbrook the Elder), who runs the small estate "Ungnade" in Mecklenburg. Klothilde, nicknamed Thildchen or Thilda, is Tony Buddenbrook's age. She grows up with her and her siblings in the house on Mengstrasse. Since she has no wealth whatsoever, she realizes early on that she will probably never find a husband. She actually remains single, initially lives as a subtenant with the widow Krauseminz and later, at the instigation of Thomas Buddenbrook, finds accommodation in the Johanniskloster, a monastery for unmarried women from long-established families with no assets. She is described as lean, pale, and phlegmatic. At the table, you notice her tremendous appetite, which she satisfies humbly and undeterred. The other family members often tease her in a harmless way, which Thilda does not annoy any further. Thekla Mann is considered her role model.

Kröger family

The rich Lebrecht Kröger (born unknown, died 1848) is the father of Elisabeth Buddenbrook, Jean Buddenbrook's wife. As a child, his granddaughter Tony is often a guest for a few weeks in his house, which is more luxurious than his parents' house. Lebrecht Kröger is a cosmopolitan older man of the old school who often gives generous gifts. In the novel he is called the à la mode cavalier . The experience of the riots of 1848 affected him so much that he died on arrival at his doorstep (possibly of a stroke) after a nightly carriage ride through the street riots.

His son Justus Kröger (born 1800, died 1875) marries the shy Rosalie Oeverdieck and with her they have the children Jakob and Jürgen. He soon retires and enjoys life as a "suitier". He sells his parents' stately property, which is divided up and simple houses are built on, which outrages Tony Buddenbrook. After Jean's death, Justus is Clara Buddenbrook's guardian. His sons disappoint: Jakob always attracts attention for his carelessness and dodgy business dealings. His father broke with him when he committed a “dishonesty”, an “assault” at his employer, sent him to America and refused to speak about his son. Only Jacob's mother knows where he is and secretly sells her silver items to send money to the disinherited. Jürgen gives up his law studies after failing the exam twice and becomes a simple post office clerk in Wismar. The originally very large fortune of the Krögers is also constantly dwindling: After Justus used to give gifts that were just as generous as his father, his widow no longer even has a "presentable" dress, not least because of the constant support payments for her criminal son.

Justus dies like Thomas Buddenbrook in 1875.

The Hagenström family

Hagenström, who are new to town, are determined to compete with the Buddenbrooks. In the end, Hermann Hagenström , who is about the same age as Thomas Buddenbrook, “far surpassed him in terms of business”. He was also the first in town to light his living quarters and offices with gas . “The novelty and thus the charm of his personality, what distinguished him and what gave him a leading position in the eyes of many, was the liberal and tolerant basic trait of his being. The casual and generous manner in which he earned and spent money was something different from the tenacious, patient work of his fellow citizens, guided by strictly traditional principles. This man stood on his own two feet, free from the inhibiting shackles of tradition and piety, and everything old-fashioned was alien to him. ”If Hermann Hagenström followed any tradition,“ it was the unrestricted, advanced one inherited from his father, old Hinrich Hagenström , tolerant and unprejudiced way of thinking. ”After the death of Thomas' mother, Hermann Hagenström bought the big house in Mengstrasse. The newcomer, who barely knew his grandfather, gives himself “the historical consecration, the legitimacy, so to speak.” Hagenström's take Buddenbrook's place - just as Buddenbrook's times had been replaced by the Ratenkamps, the previous owners of the house. “Already in spring [1872] he and his family moved into the front building, leaving everything as it was when possible, subject to small occasional renovations and apart from a few immediate changes in line with modern times; for example, all bells have been abolished and the house has been equipped with electric bells. "

Morten Schwarzkopf

Tony likes the factual medical student Morten Schwarzkopf from the very first encounter. After every conversation with him, he impresses her a little more. They both fall in love and promise to wait for each other until Morten has passed his doctorate. Morten remains Tony's only love for life, which is thwarted by Tony's father through a mixture of class arrogance and shopkeeper mentality (see content, third part). Jean Buddenbrook falls for the blender Bendix Grünlich and enforces it as Tony's husband and future family member.

In his talks with Tony, Morten Schwarzkopf represents the liberal standpoint of the bourgeoisie towards the nobility and patrician bourgeoisie. He has little respect for state authorities and has a skeleton that he has put on in a police uniform; he is a member of a fraternity . Toni doesn't quite understand his political views, which are ultimately directed against her own social class, in their naive way, but is nevertheless impressed by his statements. She was also impressed by his scientific knowledge; many years later, when her mother died, she repeated his remarks about "stick flow", a pulmonary edema . The expression “sit on the stones”, which recurs as a leitmotif: Morten Schwarzkopf has to sit on the stone breakwaters away from the elegant beach life and wait for Tony, is indicative of her relationship with the likeable, but from Buddenbrooksches point of view, not befitting Morten. He does not want to show himself to her circle of friends because he feels that he does not belong to them.

Greenish goes bankrupt despite the sizable dowry from the Buddenbrook family. Morten Schwarzkopf becomes - as the proud father later reports - a successful doctor in Breslau (“un hei hett ook all 'ne state practice, the kid”).

Bendix Grünlich

18-year-old Tony gets to know him as a business partner invited by her father to join the private family circle:

“Coming through the garden, hat and stick in the same hand, with rather short strides and slightly forward head, came a man of medium height, about 32 years old, in a green and yellow, wooly, long-lipped suit and gray thread gloves. His face, beneath his light blond, sparse hair, was rosy and smiled; but beside one nostril there was a noticeable wart. His chin and upper lip were shaved and his whiskers hung down long in the English fashion; these favorites were of a decidedly golden yellow color. - Even from a distance he made a gesture of devotion with his large, light gray hat. "

Antonie abhorred him from the very first moment because of his mannered speech and exaggerated gestures, and she quickly saw through that he was telling her parents exactly what they wanted to hear. After a few weeks he proposes to her. Tony refuses. Stubborn and scheming, he tries to get Tony: Grünlich seeks out Morten Schwarzkopf's father and informs him about his marriage plans with Tony, whereupon Morten's father forbids his son to deal with Tony. By skillfully influencing Tony's parents, he finally got married to her.

What looked like being in love turns out to be a calculation. After the wedding, he hardly takes any notice of his young wife. The only thing that mattered to him was the dowry and his creditworthiness as the son-in-law of the Buddenbrook family, which is why he had made the engagement to Tony public even before it took place. In the end, however, his calculation did not work out: Although he had initially received further loans from the banks due to his relatives to Johann Buddenbrook, when he finally became insolvent, his father-in-law refused to pay Grünlich's debts.

Because of Grünlich's bankruptcy , Tony divorced him and returned to their parents' house with their daughter.

Alois Permaneder

“Short-limbed and stout, he wore a wide-open skirt made of brown loden, a light-colored, floral vest that gently curved his belly [...]. The light blonde, sparse, fringed mustache hanging over the mouth gave the round head with its squat nose and rather thin, unstyled hair something seal-like. "His face had a" mixed expression of resentment and honest, clumsy, touching good-naturedness. "

Unforgivable and not to be reproduced under any circumstances is the swear word that Alois Permaneder called after his wife Tony. Many pages of the novel leave the reader in the dark about Permaneder's final words.

“Later, in some way that was never enlightened, individual family members became aware of the 'word', that desparate word that Herr Permaneder had let himself slip that night. What did he say? ”-“ Go to the Deifi , Sau lud'r dreckats! ”-“ So Tony Buddenbrook's second marriage. ”

However, Permaneder is actually a good-natured person. The death of his little daughter hits him very hard. He also has no grudge against Tony, but willingly gives back her dowry after the divorce and years later congratulates the Buddenbrook company by telegram on the anniversary.

Kai Graf Mölln

Kai is Hanno's only friend, "of noble origins and completely neglected appearance". He lives with his father at the gates of the city on his "tiny, almost worthless property that had no name at all". "Motherless [...] the little quay here grew up wild like an animal among chickens and dogs." From the family tree of the count's family, only he and his father still exist, the family estate is anything but stately, but looks more like a simple one Farm. His father's behavior also leaves a lot to be desired. Ida Jungmann is shocked when she visits there with Hanno and encounters the exact opposite of the expected noble nobility. However, aristocratic self-confidence has been retained in Kai. In addition, he is bursting with vitality, is enthusiastic about English literature and an imaginative narrator, without his interest in literature (he also writes himself) foreign to him. There is no (family) history burdensome on him, and he does not feel obliged to civic conventions. The decline of his family did not render him unfit for life. Unlike the sensitive Hanno, Kai doesn't suffer so much from the teachers, but makes fun of them.

Kai and Hanno feel drawn to each other from the first moment. The more active in this friendship is Kai. He “had campaigned for the favor of quiet [...] Hanno with a stormy, aggressive masculinity, who could not be resisted at all.” - A Count Schwerin is regarded as a model for the character in the novel .

Ida Jungmann