Upper Castle (Heidelberg)

| Upper castle | ||

|---|---|---|

|

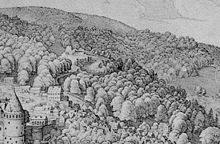

The upper castle (right) after Sebastian Münster from 1527 |

||

| Alternative name (s): | Old castle, old castle, castle on the mountains | |

| Creation time : | 1000 to 1200 | |

| Castle type : | Hilltop castle, spur position, moth | |

| Conservation status: | Burgstall, small remains of the wall | |

| Place: | Heidelberg | |

| Geographical location | 49 ° 24 '25.3 " N , 8 ° 42' 46.2" E | |

|

|

||

The Upper Castle , and Old Castle, Old Castle, castle to mountains called, is an Outbound hilltop castle on the little Gaisberg above the Heidelberg Castle in Heidelberg in Baden-Wuerttemberg . Like Heidelberg Castle, the complex already existed in the High Middle Ages , but was destroyed in 1537 by lightning and an explosion of powder supplies. Today the site of the castle is essentially built over with the whey cure .

history

There are documented references to a castle in Heidelberg from 1225. Until 1294, only one castle is mentioned, in 1303 two castles for the first time. In the future, the castles were differentiated according to their location, whereby the castle was called the Upper Castle in today's Molkenkur , as it is higher than the castle complex on the site of today's Heidelberg Castle on the Jettenbühl . Whether the facility at the whey cure is older than the castle on the Jettenbühl cannot be said without major excavations. Architectural parts found in Heidelberg Castle also suggest a date in the 13th century there. A unanimous opinion about which of the castles is older has not been formed for a long time, even taking into account archaeological findings in the city area, where the associated castle hamlets were to be located.

Only the latest findings suggest that the upper castle is the once more important castle and that its associated hamlet was in the area of St. Peter's Church . The decline in importance of the Upper Castle, major structural changes in the area of the Peterskirche settlement and the founding of Heidelberg with a walled city in the area of today's old town coincide with the upswing of today's castle. At the same time, there are also indications that the settlement near the Peterskirche was even older than the Upper Castle and could not have had any relation to it. The Upper Castle and St. Peter's Church, located outside the medieval city walls, were both relics from the time before the city was founded in the late Middle Ages.

When the Palatinate was divided in 1338, the formulation Haydelberg burg und stat and die ober burg was used to establish a closer relationship between today's castle and the city; from the middle of the 14th century, today's castle was the residence of the Electoral Palatinate, while the upper castle was later Documents rarely occurs and is already referred to as old from the 15th century .

In 1364 the upper castle was occupied by guards from the Electorate of the Palatinate. In 1503 there were three hackney busses on the old castle . In 1515, students were banned from staying in the vicinity of the old castle. It is reasonable to assume that the castle was a part of their defense system at the latest since the upgrading of today's castle to a residence and, due to its exposed location, it was also a symbol of power for the electors. The residence ban issued to the students could be related to the storage of explosives in the upper castle.

The castle is indicated in 1485 on the oldest known view of Heidelberg on a woodcut from the workshop of Johann Prüss and in 1526/27 on a mirror-inverted view by Sebastian Münster as a prominent part of the cityscape above the Residenzburg. A more precise idea of the appearance of the castle is provided by a drawing in the holdings of the Kurpfälzisches Museum, which is attributed to the hand of Count Palatine Ottheinrich from 1537 and which is the template for many later depictions, among others. a. by Heinrich Hoffmann and Theodor Verhas , bot.

A lightning strike on the afternoon of April 25, 1537 triggered an explosion in the castle's powder magazine, which, according to archival sources, contained 200 tons of powder. The events are recorded in a letter from an eyewitness, the Palatinate humanist Jakob Micyllus . He reports the extensive destruction of the entire facility within a single instant. There were five injured and two dead among the nine residents of the outer bailey. The huge explosion threw stones in a wide area through the air. When Palas of the lower castle man by a falling rock was hit.

The stone material left over from the castle was probably used quickly for Ludwig V's extensive building projects , as most of it was soon removed. Already in Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia from 1550 only a few foundation walls of the castle are shown. In 1617 an English traveler mentioned the ruins in his travel diary. In his city panorama of Heidelberg from 1620, Matthäus Merian also shows the remains of the wall at the location of the upper castle and mentions the destruction by explosion in the legend.

During the siege of Heidelberg by imperial troops under Tilly in 1622, the area at the Molkenkur was re-fortified from ruins of the castle with a fortification and was intended to protect the flank of the castle again. As a result of this construction work and the months of attacks by the imperial family, most of the remains of the castle were lost. The castle hill was razed in 1693.

In 1805 Friedrich Peter Wundt described in his first topographical description of Heidelberg about the Burgstall, "that one should hardly believe that any house, much less a castle, was on it" . When Albrecht Wagner acquired the site in 1851 and began building today's Molkenkur, he had the site leveled for his own purposes, which meant that further structural remains of the castle were lost. On Karl von Gramberg's view of the whey facility from 1860 (based on a model from 1856), some hewn stones cleared to one side can be seen in the foreground. Such were found scattered on the site when the city of Heidelberg acquired the whey cure in 1906. The popularity of the Molkenkur restaurant has ensured that the term "Molkenkur" was also adopted in the land registry office for the castle site, so that the old castle gradually disappeared in the minds of the citizens and is only the subject of scientific discussion, especially in relation to today's Castle, was.

The Heidelberg Castle Association carried out excavations at the castle in 1900/01, which, however, did not uncover any sensational finds. The excavation documentation was lost after the death of the excavator Karl Pfaff in 1908. Only a short summary by Pfaff and a newspaper report from 1901 still provide some information about the excavation finds at that time. The few uncovered remains of the wall were not considered worthy of preservation, so that they continued to fall into disrepair, were partly used as a quarry and most of them were leveled again and the areas were later paved. The neck ditch was also expanded and paved as an access route to the whey cure.

In 2001 a new excavation took place, which followed Pfaff's fragmentary findings and allowed the remains of the wall noted by Pfaff to be mapped, but hardly brought any further findings on the buildings. Because some parts of the site have been removed to below the former foundation area, no more wall can be excavated for essential areas of the former castle complex. The stones and other finds found loosely in the area indicated a settlement focus in the 12th and 13th centuries. The facility was expanded around 1300, so that little traces of settlement, but a lot of building material from that time can be identified. In the late 14th and 15th centuries, the castle was then used more intensively and from the 16th century onwards, the finds gradually demolished, before there was a high density of finds again since the time of gastronomic use in the 19th century.

investment

The remains of a mountain moth from the 11th / 12th centuries as well as high medieval buildings, including an approximately rectangular "fort" in the area of the former outer bailey, can be detected . The facility was intended to secure the lower south-west flank of the castle. It had a total area of 130 by 38 meters, the main castle a side position of 38 by 31 meters. Deep neck trenches cut the fortification in the spur position from the higher mountain slope.

In addition to the ramparts from the time of the Thirty Years' War , a few remains of the outer bailey, the tower hill , the neck ditches and on the north side the “Teufelsloch” quarry are still visible. The only remaining wall remnants of the southern ring wall of the castle is in the southeast of today's Molkenkur parking lot and does not begin on the adjacent rock until about half a meter above the parking lot level, which is also impressively demonstrated by the many leveling work that took place after the end of the castle. Many other old walls in the area around the Molkenkur were only built as hillside retaining walls in the 19th century.

literature

- Hans Buchmann: Castles and palaces on the Bergstrasse , therein: Die Burg zu Berge , Stuttgart 1986, pp. 223–226

- Christian Burkhart: The upper castle in Heidelberg: The forgotten Palatine Palace , publisher: Johannes Gutenberg School Heidelberg, Heidelberg 1998, 32 pages

- Friedrich Franz Koenemann: Hikes through Heidelberg forests - goals along the way , Heidelberg 1990

- Rainer Kunze: Die (3) Heidelberger Burgen , In: Mannheimer Geschichtsblätter , NF 4/1997

- Ludwig Merz: Obere Burg and Burgschanze over Heidelberg , In: Unser Land , Heidelberg 1994, pp. 153–157

- Thomas Steinmetz: Castles in the Odenwald. , Verlag Ellen Schmid, Brensbach 1998, ISBN 3-931529-02-9 , p. 62f.

- Thomas Steinmetz: Castles and the city of Heidelberg in the mirror of earlier documented sources , In: Burg und Stadt , Munich 2008, pp. 159–168

- Achim Wendt and Manfred Brenner: "... des lieux depuis si long-temps condamnés au silence". Archaeological search for traces on the upper castle on the Molkenkur , in: Heidelberg. Yearbook on the history of the city 2003/04 , pp. 9–40

Web links

- The fortifications on the Molkenkur (PDF file; 231 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas Steinmetz: Castles in the Odenwald. Brensbach 1998, p. 62f.

- ↑ Wendt / Brenner 2003/04, pp. 32-36.

- ↑ Hans Martin Mumm: From the foundation of the city. Three studies . In: Heidelberg. Yearbook on the history of the city 2009 , pp. 9–20, here p. 15.

- ↑ Published in Strasbourg in 1485 , it is now in the Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart : Inc. Fol. 4081, Bl. XI (according to the chronological table of Heidelberg history 1400-149 9 on the website of the Heidelberger Geschichtsverein eV (HGV))

- ^ Günter Augspurger: The old castle. Heidelberg's “Obere Burg” and the painter Heinrich Hoffmann , in: District Association Handschuhsheim e. V. (Ed.): Yearbook 2010 , Heidelberg 2010, pp. 112–115.