Bullfinch

| bullfinch | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

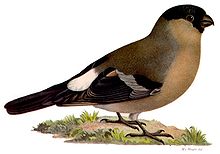

Bullfinch ( Pyrrhula pyrrhula ), male |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Pyrrhula pyrrhula | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The Bullfinch ( Pyrrhula pyrrhula ), also Bullfinch or rare blood Fink called, is a bird art from the family of finches (Fringillidae). It settles in Europe , the Middle East , East Asia including Kamchatka and Japan as well as Siberia . Both in the lowlands and in mountain forests survived the bullfinch in coniferous forests , mainly in spruce - plantations , but also in sparse mixed forests with little conifers or undergrowth. Its diet consists of semi-ripe and ripe seeds of wild herbs and buds . The species is currently not considered endangered.

In the past, the bullfinch was a symbol of clumsiness, clumsiness and stupidity. It can often be found as a decorative background motif on old depictions of the Garden of Eden .

description

Like all members of the genus, the bullfinch is of a stocky shape with a short neck and thin feet. It is characterized by a black headstock, a black chin and a thick, black conical beak. The black wings have a white band. The rump is white, the tail black. The eyes are deep brown. Bullfinches have a body length of about 15 to 19 centimeters. The wingspan is 22 to 26 centimeters and the body weight is usually around 26 grams.

The bullfinch shows a clear sexual dimorphism . The male has a blue-gray back. Wing bands, lower abdomen, lower tail and rump are white, cheeks, chest, flanks and upper abdomen are bright rose-red. The feet are black-brown. The female has a brownish-gray back. The chest, flanks and underside are light gray-brown in color with a very slight tinge of reddish. The feet are blackish.

The young birds have a more brownish plumage than the similar females. The beak is without black. The head is light, but in the juvenile moult it slowly turns black after six to eight weeks. When flying out, young males have a slightly reddish tinge on the chest. Hatched nestlings are characterized by long, gray down on the head and back. The pink throat is provided with a purple-gray spot on the left and right. The beak ridges are yellow. Both the juvenile moult (a partial moult) and the breeding moult of the adult birds, a full moult, take place in Central Europe from August to October. The full moult lasts about 80 to 85 days.

The bullfinch is unique among passerines (Passeriformes) in terms of its sperm . While this is usually pointed and spiral-shaped, this bird is characterized by a round head and a blunt acrosome . Furthermore, the testes are very small in relation to the body size of the bullfinch, which is justified by a lack of competition between the sperm.

Voice and singing

The Gimpel's voice- touch call is expressed in a quiet “bit-bit”. The call is expressed by a soft “djü” or “diü”. It can be heard frequently and relatively far, mainly outside the breeding season, especially from swarms in autumn and winter. In the breeding season it serves to communicate with the partner and as a sign of identification. When excited, bullfinches utter a "dü-dü", while fearful they let you hear a "chrüääh". The aggression call consists of repetitions of a loud "chier-chier". Northern bullfinches of the subspecies P. p. pyrrhula can be clearly identified by the call of the birds of the subspecies P. p. Europaea differentiate: Instead of the soft “djü”, a “dööd” sounds, which is strongly reminiscent of the double-barreled plastic toy horns. This distinctive reputation has given the North European subspecies the nickname “Trumpeter bullfinch”, which is difficult to distinguish visually.

The call of the young birds represents a soft “di-di-di”. From the fifth day these sounds change to a “dsrieh-dsrieh”, from which the begging call gradually emerges, which resembles a loud, stretched “dü-i -eh "sounds. Full boys utter a quiet "rr-rr". In the first few days, the female requests to block with a deep "ooo". Young birds that have flown out regularly give a "diel-diel" as a call to their location.

The bullfinch's song is soft and performed with a twitch of its tail. It consists of whistling tones interrupted by creaking and croaking sounds. With the subspecies P. p. europaea and P. p. coccinea it is performed fluently, while P. p. pyrrhula the tones are interrupted by pauses. In addition, P. p. pyrrhula significantly deeper than the two aforementioned. The song is not important when marking the territory, as the bullfinch shows territorial aggression only in the nest area. Singing is shaped by the male singing from an early age.

From September to the end of February, the females sing as loudly and continuously as the males, but stop singing when the mating season begins.

Hand-reared bullfinches can mimic melodies if taught to them as fledglings. There is an experiment in which ornithologist Jürgen Nicolai whistles the song Ein Jäger from Kurpfalz to a young bullfinch (seen in the film Eating and being eaten ) and the bird tries to whistle the tune.

distribution

The bullfinch colonizes Europe , the Middle East , East Asia including Kamchatka and Japan as well as Siberia . The southern border runs roughly at the level of northern Spain , the Apennines , northern Greece and northern Asia Minor . The bullfinch inhabits both the lowlands and mountain forests, but is absent in areas with little trees and above the forest zone (2000 m). He is a standing and mooring bird . Many northern populations migrate south.

habitat

The Bullfinch lives in coniferous forests , mainly in spruce - plantations , but also in sparse mixed forests with little conifers or undergrowth. It can also be found on the edges of clearings , on clearcuts, as well as on paths and aisles . The bullfinch also frequently visits parks and gardens . However, conifers, especially spruces, must be present here. It is rarely found in cemeteries or biotopes that are overgrown with birch trees and thick bushes. In spring he often looks for fruit plantations or orchards .

nutrition

The bullfinch feeds mainly on semi-ripe and ripe seeds of wild herbs and trees, as well as on buds . Occasionally he eats berries and insects . There are mainly the seeds of nettle plants , Blackberries and the birch and spruce preferred and similar plants. During the summer the bullfinch feeds on the seeds of the dandelion , chickweed and shepherd's purse . It also frequently eats the seeds of forget-me-nots , goose thistle , dock and knotweed . The preferred buds of fruit trees are eaten only in winter and spring.

Reproduction

The bullfinch leads a monogamous brood marriage. Pair formation probably begins before winter sets in, but is often in February. There is still no evidence of lifelong cohesion. The bullfinch reaches sexual maturity in the first year of life. The breeding season is between April and August.

Pair formation

After the juvenile moult, when two unknown bullfinches of different sexes meet, a ritual begins that is important for pairing. The female initially flies with her belly plumage threateningly fluffed up and beak open with hoarse "Chuäh calls" towards the male. Since the male has an instinctive inhibition of attacking females, he usually responds by either flying away quickly or by showing off. However, if the male remains seated without showing any impressive behavior, it will be attacked and injured by the female, calling "chier-chier". If they do not take the opportunity to escape in time, they can be seriously injured or killed.

If the male is interested in the female, he carefully takes a few steps back. From there it tries in turn to shorten the distance with inflated belly plumage and with its tail turned towards the female until the female ceases to hostility. After reaching the female, it touches the female's beak, quickly turns away from her and hops to one side. If this reacts with the same gesture, this ritual is repeated several times. In between, one of the two flies away briefly, but quickly returns to continue with the beaks.

As soon as both birds have decided in favor of each other, tenderness feeding occurs. Here, the female begs the male like a young bird ( infantilism ) by crouching and locking with trembling wings. The male stands up and feeds from the crop. This ritual serves to ensure the dominance of the male.

Courtship and mating

As soon as the gonads have developed, the male can initiate courtship by offering the female a stalk to advertise. To do this, it moves back a few steps with the stalk in its beak and tries to shorten the distance to the female with its belly plumage raised and its tail turned towards the female. After reaching the female, she puts the stalk in her beak, quickly turns away from her and hops to one side. If the female accepts the gift, it begins to beak with the male. If the straw collar has brought about harmony, both partners fly around with nesting material.

The female asks the male to mate by luring the male with soft tenderness sounds like "die-die-die" and crouching down with trembling wings and swinging body movements for copulation . One or both partners can have nesting material in their beak. Mating can take place several times in a row and mostly in the early hours of the morning, less often over the day. At an advanced time of the year, all introductory actions are sometimes dispensed with, but tenderness-feeding is usually made up for.

Nest building and brood

The couple flies together looking for nesting sites. If the male sees a suitable place, it sits down there and gives the quiet nest lock call "chruiehr" from itself. If the female takes the place, she starts building the nest. The nesting place is usually at a height of between 120 and 180 centimeters in a dense spruce. However, it can also lie in other conifers or in thick bushes. While the female builds the nest, the male accompanies it, who every now and then takes a stalk in its beak and lets it fall after a short time. The ring-shaped nest is first built from fine, dry spruce veins. Then thin twigs , roots , herb stalks and stalks are added. Moss is rarely used. Usually the nest is ready after five to six days. Mating and tenderness feeding are continued regularly.

Eggs are laid every day in the early morning hours. Only after the last egg has been laid does the female begin to incubate the clutch on her own, so that the young birds do not hatch with a delay. During the breeding period of 13 to 14 days, the female is regularly supplied with food by the male, usually on the nest. A clutch usually consists of four to six oval eggs. These are sparingly provided with deep purple-brown to almost black spots on a light blue to blue-green, sometimes cloudy bluish background towards the blunt pole.

Development of the young birds

The young birds are born blind and naked. For the first six days , the female tucks and feeds them from the crop with what it regularly receives from the male. The food initially consists of aphids , ants and small snails . The female also initially eats the droppings, after a few days it is deposited by both adult birds on a distant branch. On the eighth day, the brownish-colored boys open their eyes and immediately raise their heads up begging, open their beaks wide and also make typical vocalizations (locks). The adult birds now fly together in search of food and return to feed together. The food now consists mainly of seeds. From the sixteenth or seventeenth day, the nestlings can leave the nest in case of danger. Sometimes they can do this by the twelfth day.

After flying out, the young sit in the branches and regularly let their position be heard so that the adult birds can provide them with food. From the 20th to the 24th day the boys eat independently, on the 35th day they are independent. They are in danger from cats , birds of prey and martens .

Free-living birds live a maximum of six to eight years. However, life expectancy is only three years on average. Up to 17 years are possible in captivity.

behavior

The bullfinch is diurnal and not very territorial. So he defends the nest area, but not a territory . During the breeding season it behaves very inconspicuously as it looks for protection in hedges or in thickets. However, it is easy to spot in winter. The bird's flight is relatively slow and undulating.

At all times of the year, with the exception of moulting , the behavior of pair formation and courtship takes place. During the breeding season, couples and families stay individually. Only in late autumn do small groups with up to ten animals and larger swarms form, which dissolve again between the end of February and the beginning of March. Mostly the proportion of males corresponds to that of females. However, some birds spend the winter in pairs. This includes especially old bullfinches, who usually prefer to stay with their partner.

If two same-sex partners are found among the young birds in summer, they can stick together in autumn and winter, only to separate in the following spring.

Systematics

External system

From the discovery of a bone in the Vitina formation (Quartaccio quarry) near Rome , research suggests that ancestors of the bullfinch from the middle Pleistocene lived there. The humerus , which is less than 20 mm in size , is characterized by a broad central barrier that is shifted to the front, which is not typical for other finch taxa (Fringillidae).

Outside the genus Pyrrhula , the golden siskin ( Carduelis tristis ) and the purple raspberry ( Carpodacus purpureus ) are the closest relatives of the bullfinch.

By comparing the sperm morphology of Pyrrhula pyrrhula and Pyrrhula erythaca , it was found that both have more differences than other closely related species.

Internal system

Different sources assume different numbers of subspecies. According to ITIS there are three subspecies : Pyrrhula p. pyrrhula is the nominate form , plus the cassing finch ( Pyrrhula p. cassinii ) and the Azores bullfinch ( Pyrrhula p. murina ) as subspecies. Nine subspecies are recognized by Avibase:

- Pyrrhula p. pyrrhula is the nominate form. It lives from Scandinavia to Eastern Europe and in northern and central Siberia to the southern Sea of Okhotsk .

- Pyrrhula p. europaea lives on the European mainland. It can be found in the area from Denmark to the lower Oder . The southern border is formed by the northern Lower Saxony and the Rhine-Main triangle . He also lives in the Netherlands , Belgium and Eastern France .

- Pyrrhula p. pileata inhabits the British Isles .

- Pyrrhula p. rossikowi lives in northern Asia Minor , especially in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia .

- Pyrrhula p. iberiae populates the north of the Iberian Peninsula , including the Pyrenees .

- The gray raspberry ( Pyrrhula p. Cineracea ) is monotypical. The male is without red and has a gray belly. He lives in southern Siberia in the area from Altai to Dauria and in the mountains of northern Mongolia .

- The Japanese bullfinch or Ussuri bullfinch ( Pyrrhula p. Griseiventris ) is an intermediate transitional form of P. p. cassini and P. p. cineracea . The male wears red sides of the head and a red band under the chin, which partly still colors the breast, otherwise the underside has a light blue-gray shimmer. It settles in Hokkaidō , Honshū , Sakhalin and the Amur - Ussuri region .

- Pyrrhula p. caspica lives in the areas bordering the Caspian Sea to the south and east .

- The Cassin bullfinch ( Pyrrhula p. Cassinii ) inhabits Kamchatka , the northern Kuriles and the coastal areas of the northern Sea of Okhotsk.

The Azores bullfinch ( Pyrrhula murina ) (Godman, 1866) is monotypical. The male is without red and has a gray belly. He only inhabits the island of São Miguel in the Azores . Here it represents a species of its own that is considered critically endangered (CE). According to phylogenetic studies, the Azorean bullfinch differs fundamentally in mitochondrial DNA from the British and Northern European bullfinches. These differences are greater than among the species in the genus Loxia in Great Britain , but the DNA of the Iberian birds must be taken into account to fully clarify this issue .

Wolters assumes nine subspecies and four species: The bullfinch ( Pyrrhula pyrrhula pyrrhula ) is the nominate form, also P. p. europaea , P. p. pileata , P. p. rossikowi , P. p. iberiae , P. p. coccinea resp. germanica as an intermediate transitional form from P. p. pyrrhula and P. p. europaea and P. p. caspica . The Kuril bullfinch ( P. p. Kurilensis ) has a thicker bill than P. p. griseiventris . Investigations of the mitochondrial cytochrome b of 24 species of goldfinch-like found that the phenotype of the subspecies Pyrrhula p. cinerea and P. p. griseiventris is concordant with the molecular subspecies status . Other species are the gray bullfinch ( Pyrrhula cineracea ), the Japanese or Ussuri bullfinch ( Pyrrhula griseiventris also as subspecies P. p. Griseiventris or P. p. Rosacea ) and the Cassin bullfinch ( P. p. Cassini ) and Azores Bullfinch ( Pyrrhula murina ).

Inventory and inventory development

The global distribution area of the gimp is estimated at 18,000,000 km². The large global population comprises around 45,000,000 to 150,000,000 individuals. Therefore the species is classified as not endangered (LC).

The European breeding population accounts for less than half of the global distribution. It is very large with more than 7,300,000 pairs and was stable between 1970 and 1990. Although there were declines in some countries, particularly France , between 1990 and 2000 , the key population in Russia was stable. The trends in most of Europe were stable or increasing. Since the population as a whole is stable, the bullfinch is consequently classified as secure.

Bullfinches and Human

Etymology and naming

In 1758, Carl von Linné referred to the bullfinch as Loxia pyrrhula . The name Gimpel is derived from the Bavarian-Austrian word gumpen (hop). He is metaphorically often applied to a gullible, as the bird earlier by mimicking the soft Stimmfühlungsrufs or by an already captured decoy was easily catch.

The name bullfinch comes from the fact that the compact, sedate figure with the red robe and black cap was associated with a canon by some people . Other names are blood finch, Rotgimpel, Rotfink, Rotvogel, Pollenbeißer (Bud biter), Gücker and Goll. In East Westphalia the blood finch is called bleotfinken , in the Bergisches Land the blue finch or blotfink and by Erkelenz Blootvenk . In Rheinberg there is a saying: “Dän ös schtols wi ene Gempel.” (High German: “He is proud like a bullfinch.”) In Great Britain the bullfinch is called a bullfinch , in the Netherlands as a goudvink ( gold finch ).

From the 1920s to the 1960s he was known as an advertising figure for a floor wax ( bullfinch noble wax ).

Cage husbandry, conservation and consumption

In the 19th century the bullfinch was often kept in the craft room. The dominance of English trading houses with extensive connections ensured that they set trading prices before German wholesalers. This competition reduced the profit margin of the quality-minded small traders, who had built up an important line of business over time by trading in bullfinches. In Vogelsberg and Thuringia the bullfinch was taught to whistle songs when trained. Small bullfinches, especially of the subspecies P. p. coccinea , were considered to be particularly capable of learning. The birds were taken out of the nest before they left the nest, so that several times a day they could whistle the song to be learned bit by bit. When they mastered it, the process was repeated with a new section until the song was complete. Talented bullfinches could master up to three songs. In addition, young bullfinches learned through the singing of other songbirds, especially the canary . The birds bred were exported from Germany to the USA .

The bullfinch is kept as a cage bird to this day. If you are interested, breeders will sell animals. Further education through appropriate literature before purchasing these animals is necessary. Bullfinches can be kept both in the cage and in the planted aviary if they are fed appropriately. The feed should be varied and consist mainly of semi-ripe and ripe seeds of wild herbs.

In Germany, taking from nature as eggs or by lifting young birds from nests has been prohibited since July 1, 1888, and wild-caught animals and the trade in animals obtained in this way are largely prohibited. In the implementation of the EU Birds Directive of 1979, which had this as its goal for the entire European area of the EU , extensive access and (with certain exceptions) marketing and ownership bans apply to all specimens of native wild bird species.

Bullfinches were consumed in Germany well into the 19th century. In Italy this is still the case in some cases, although the EU Birds Directive applies there as well.

The bullfinch in art

- The bullfinch can often be found as a decorative background motif on old depictions of the Garden of Eden . For example, bullfinches are depicted in the painting “ Representation of Paradise with the Fall of Man ” (1615) by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens . The former also depicted the species in the painting " Paradise landscape with Noah's ark " (1596), on which the gathering of animals in front of Noah's ark is shown.

- In Otfried Preussler 's children's book The Robber Hotzenplotz , the evil magician Petrosilius Zwackelmann turns the man into a bullfinch and puts it in a cage.

- In Gypsy Baron by Johann Strauss says the duet "Who dared us" with Saffi and Barinkay: "The Bullfinch, who married us!".

- The main character of the film The Ice Cold Angel , Jef Costello, holds a female bullfinch in a cage with which he shares his otherwise sparsely furnished apartment. Considering the film, the bird is interpreted as a counterpart to the routine, largely emotionless world of the protagonist.

literature

- G. Aubrecht: The Azores bullfinch - pursued, lost, rediscovered. In: Gefiederte Welt 2/97, 1997, p. 76.

- Einhard Bezzel : FSVO manual birds. BLV Buchverlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8354-0022-3 .

- Einhard Bezzel: Compendium of the birds of Central Europe. Songbirds. Wiesbaden 1993.

- Horst Bielfeld : siskins, giraffe, bullfinches and grosbeak. Origin, care, species. Ulmer-Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-8001-3675-9 .

- Classen / Massoth: Handbook for Cardueliden. Volume 2, Pforzheim 1994.

- F. Doerbeck: On the biology of the bullfinch in the big city. In: The bird world. No. 4, 1963.

- R. Haffner: Observations in a bullfinch breeding. In: Feathered World. 4/81, 1981, pp. 71-72.

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim : Handbook of the birds of Central Europe. Volume 14/2: Passeriformes. Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-89104-610-3 .

- J. Jung: Fifteen-year-old observations and breeding of the bullfinch. In: Canary friend. 8/87, 1987, pp. 212-216.

- Gerard Le Grand: The rediscovered Azores bullfinch. In: We and Vogel. Volume 15, No. 1, 1983, pp. 37-38.

- KG Mau: About the Japanese bullfinch. In: Canary friend. 8/91, 1991, pp. 214-215.

- J. Nicolai: On the biology and ethology of the bullfinch. In: Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. Volume 13, 1956, pp. 93-132.

- H. Schieger: The bullfinch or bullfinch. In: Feathered World. 1/84: 17-20, 2/84: 41-43, 1984.

Web links

- Videos, photos and sound recordings for Pyrrhula pyrrhula in the Internet Bird Collection

- NABU entry with sound sample

- Entry at the Swiss Ornithological Institute

- Information page about the Gimpel (private page)

- Another example of singing ( Memento from March 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (MP3; 1.7 MB)

- Pyrrhula pyrrhula in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on January 1 of 2009.

- Feathers of the bullfinch

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Einhard Bezzel: Compendium of the birds of Central Europe. Songbirds. Wiesbaden, 1993.

- ↑ Timothy R. Birkhead, Simone Immler, E. Jayne Pellatt, Robert Freckleton: Unusual Sperm Morphology in the Eurasian Bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula). In: The Auk. Vol. 123, 2006, pp. 383-392 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c Horst Bielfeld: Siskins, Girlitze, Gimpel and Grosbeak. Origin, care, species. Ulmer-Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-8001-3675-9 .

- ↑ Jürgen Nicolai: Family tradition in the development of the Gimpel's song. In: Journal of Ornithology. Volume 100, 1959, pp. 39-46.

- ↑ Birds of the Forest . In: Birds of our region . Atlas Publishing House.

- ^ C. Bedetti: Update Middle Pleistocene fossil birds data from Quartaccio quarry (Vitinia, Roma, Italy). Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza", Roma, Italy - The World of Elephants - International Congress, Rome 2001, online ( Memento from April 13, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ D. Janossy: Humeri of Central European smaller Passeriformes. In: Fragmenta Mineralogica et Paleontologica. Volume 11, 1983, pp. 85-112.

- ^ KH Voous: Distributional History of Eurasian Bullfinches, Genus Pyrrhula. In: The Condor. Volume 51, 1949, pp. 52-81 ( online ).

- ↑ Timothy R. Birkhead, Simone Immler, E. Jayne Pellatt, Robert Freckleton: Unusual Sperm Morphology in the Eurasian Bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula). In: The Auk. Vol. 123, 2006, pp. 383-392 ( online ).

- ↑ ITIS Report: Pyrrhula pyrrhula (Linnaeus, 1758)

- ↑ Avibase Database: Bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) (Linnaeus, 1758)

- ↑ Avibase Database: Azores bullfinch (Pyrrhula murina) (Godman, 1866)

- ^ DA Bannerman, WM Bannerman: Birds of the Atlantic islands. 3: A history of the birds of the Azores. Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh, 1966.

- ↑ Birdlife Factsheet: Azores Bullfinch

- ↑ JA Ramos: Action plan for the Azores Bullfinch (Pyrrhula murina). In: B. Heredia, L. Rose, M. Painter, eds: Globally threatened birds in Europe: action plans. Strasbourg: Council of Europe and BirdLife International, 1996, pp. 347-352 ( PDF file ).

- ^ JA Ramos: Status and ecology of the Priolo or Azores Bullfinch. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, 1993.

- ↑ Hans E. Wolters: The bird species of the earth. Berlin, 1975-1982.

- ↑ A. Arnaiz-Villena, J. Guillén, V. Ruiz-del-Valle, E. Lowy, J. Zamoraa, P.Varela, D. Stefani, LM Allende: Phylogeography of crossbills, bullfinches, grosbeaks, and rosefinches. In: CMLS, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. Volume 58, 2001 pp. 1–8 ( PDF file; 277 kB ).

- ↑ Birdlife Factsheet: Eurasian Bullfinch

- ^ Birds in Europe: Eurasian Bullfinch

- ^ Karl Müller: A parson popular everywhere. About rearing and training bullfinches. In: The Gazebo. Issue 11, pp. 177-179 ( online ).

- ↑ Law on the Protection of Birds of March 22, 1888

- ↑ § 44 Paragraph 1 and 2 of the Federal Nature Conservation Act (BNatSchG) in conjunction with § 7 Paragraph 2 No. 12 and 13 a bb BNatSchG, ie. "specially protected" species with consequent documentation obligations and fines and criminal offenses.

- ↑ Ulrich Behrens: The last samurai. In: filmzentrale. Retrieved August 16, 2019 .