History of Dornbirn

This article covers the history of the city of Dornbirn in Vorarlberg ( Austria ). Today's largest city in the country only gained importance from the middle of the 19th century, when the textile industry flourished in the Austrian Empire . Nevertheless, the origins of the district capital , which today has 49,872 inhabitants (as of January 1, 2020), should also be mentioned here.

Prehistory and early history

Archaeological finds in the Rhine Valley and the Walgau region show early settlement activity in Vorarlberg, particularly in the area of the Inselbergs near Götzis and Koblach . The hills of Feldkirch and the surroundings of Bregenz and Bludenz were also places of lively settlement activity. In the cattle and monk caves in Ebnit , remains of late Ice Age animals ( cave bears and reindeer ) were found, but whether these had been hunted by hunters could not be determined without a doubt. In Dornbirn municipal area, the oldest finds were human presence from Sünser yoke and the banks of Sünser lake in 1800- 1900 m above sea level. A. to be dated to the Middle Stone Age (8000 to 3000 BC). Another find, which was found in 1971 during excavation work for the new construction of the Achmühler Bridge, was identified as a disc-shaped club head made of quartzite and dates from 3000 to 1800 BC. Be assigned. It is the oldest find in the municipality that is still inhabited today.

Roman Empire

Also from the time when the area of today's Dornbirn belonged to the Roman province of Raetia , only a few finds are known in the Dornbirn municipality. In addition to some Roman coins, there is a double-button fibula from the 1st century, which was part of the women's costume of that time. The Roman road from Chur ( Curia Rhaetorum ) to Bregenz ( Brigantium ), the route of which is said to have run along the mountainside through Dornbirn, is also of archaeological interest . Neither in the time of Roman rule nor before that can be confirmed that the municipality was settled.

The Alemannic Conquest

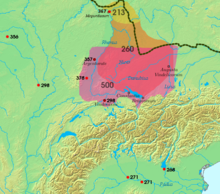

In the middle of the 3rd century warlike Germanic associations advanced from the Main to the area of what is now the German state of Baden-Württemberg . Since the Roman defense line - the Limes - was broken through, the Roman troops withdrew the defensive border on the Rhine, Lake Constance, Iller and Lech ( Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes ). Subsequently, the various Germanic tribes that had invaded this area joined together under the name of Alamanni . As a result, Alemannic combat units struck several times against the south, often also against the Alpine Rhine Valley occupied by the Romans . When the Alemanni finally ventured into the Rhine Valley after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the Franconian Duchy of Alamannia , they encountered a sparsely populated area. In 1898 a grave was discovered in Mittelfeldstrasse, which is clearly Alemannic, this is the first evidence of settlement activity in what is now Dornbirn's municipality. It is not known whether this grave, which presumably belonged to a whole burial ground and suggests a settlement in the 6th and 7th centuries, allows a connection with the later Torrinpuirron . In any case, it can be said that the first Alemannic settlement in today's Dornbirn municipality was located in the area of today's Hatlerdorf district .

middle Ages

First documentary mentions

In the year 719 the monastery of St. Gallen was founded by Otmar von St. Gallen . Within a very short time this became one of the most important spiritual and cultural centers as well as an important power factor. Dornbirn owes its first documentary mention to the numerous possessions of the monastery. A certificate made on October 15, 895 about an exchange of land with a landlord named Hadamar has a contemporary archive note on the back. The Latin original text of this memo is Concambium Hadamari de Schostinizinisvvilare et Torrinpuirron , translated into German that means something like "Exchange of Hadamar to Schostinizinisvvilare and Torrinpuirron". It is considered proven that Torrinpuirron refers to the former settlement in the area of today's Dornbirn. Unfortunately, even after intensive research, it has not yet been clarified where the mentioned area of Schostinizinisvvilare is. Torrinpuirron, on the other hand, stands for The Courts of Torro , whereby Torro was a common Alemannic name at the time (it can be traced back to the year 772 in St. Gallen documents) and the eponymous Torro could be a local farmer who was a settlement of several Höfen (corresponding to the Alemannic settlement forms prevalent at the time) in Niederdorf , today's city center near St. Martin's Church. The second part of the place name, -büren or -beuren was translated as settlement, house, which in turn confirms the above translation as settlement or courtyards of Torro. It was not until 62 years later, on May 21, 957, that the name Thornbiura first appeared as an official part of a document. In this text it is said that the two brothers Engilbret and Huprehen transferred all of their property, which they owned in the villa ( lat. Village) Thornbiura , to the monastery of St. Gallen and that they are due for an annual Martini (November 11th) , Received interest from one pfennig as beneficum ( Latin fiefdom) for management purposes . For the purpose of this donation, the then St. Gallen Abbot Cralo personally came to Dornbirn to take part in the notarization. The two brothers Engilbret and Huplassung are likely to have had a high social status, similar to the nobility , and were accordingly important people that the abbot personally - at that time one of the most important and powerful men in the region - attended this certification.

St. Gallen Kellhof in Dornbirn

As already described, the St. Gallen Monastery had a significant influence on the development of the entire Rhine Valley region very early on. After all, the monastery had achieved such great importance that several villages were completely under the monastery (for example Höchst ). The center of such villages was usually a so-called Meier or Kellhof . These were named after the officials who headed them, the Meier ( villicus ) or cellar ( cellarius ). There was also a Kellhof in the Dornbirn settlement. This can be derived, among other things, from the date on which taxes had to be paid in the late Middle Ages and early modern times : St. Othmarstag, the name day of the founder of the St. Gallen monastery. According to research, this Kellhof was located immediately south of the parish church of St. Martin, west of the market street that now exists at the level of the confluence with Schillerstraße.

Rule of the Counts of Bregenz

In the Frankish empire of the Carolingians , the empire was divided into different districts , which officials presided over as the king's deputies. These bore the title comes ( counts ). Those counts who ruled over the Rheingau ( Ringowe ), to which Dornbirn belonged, in the Frankish Empire were the Counts of Bregenz. These came from the noble family of Udalrichingen , which was named after the frequently used name Uodalrich ( Ulrich ). Thanks to a distant relationship with Emperor Charlemagne , this family was able to acquire and maintain the majority of the count's rights on Lake Constance and in the Alpine Rhine Valley . The Counts of Bregenz and the St. Gallen Monastery soon developed into bitter rivals on questions of property policy. These disputes reached their preliminary climax in the 11th century in the context of the Europe-wide investiture dispute . In the context of this dispute, the St. Gallen monastery supported Emperor Heinrich IV , while the Bregenz counts supported the policy of Pope Gregory VII . With the Guelphs , one of the most important Swabian count families also held on to the Pope . When Duke Welf IV made a campaign southwards along the Rhine in 1079 , he apparently annexed the St. Gall possessions and then distributed them as spoils of war to his house monastery, the Benedictine Abbey of Weingarten and the women's monastery at Hofen near Friedrichshafen . The Dornbirner Kellhof should therefore have belonged to the Weingartener, while the St. Martin's Church belonged to the Hofener monastery. It seems that the Counts of Bregenz were also given Dornbirner Gut as a gift, because in the late Middle Ages a considerable estate of the Mehrerau Monastery , which was founded by Count Ulrich X. von Bregenz, can be found in Dornbirn. The courtyards of the Hofen and Mehrerau monasteries were not far from each other, which suggests that they once formed a unit and were only separated afterwards when they were donated to the Counts of Bregenz. After this forcible appropriation of the St. Gallen property, the balance of power in Dornbirn also changed in favor of the Counts of Bregenz. From then on, they not only exercised high jurisdiction , but also the lower jurisdiction previously exercised by the monastery . These court rights of the Bregenz residents were not jeopardized, as none of the three religious institutions in Dornbirn (Hofen Monastery, Mehrerau and Weingarten) had the necessary basis to dispute them.

Rule of the Counts of Montfort

In 1150, Count Rudolf von Bregenz, the last male member of the udalriching aristocratic family of Bregenz, died. His inheritance was shared by his son-in-law, Count Palatine Hugo I of Tübingen, and a distant relative of the deceased, Count Rudolf von Pfullendorf . When Count Palatine Hugo died in 1182, he left Rudolf, the older of his two sons, the title of Count Palatine and all of the Tübingen possessions. His younger son, named Hugo , received goods and rights from the inherited Bregenz inheritance. This Hugo built a castle near Götzis around 1200 , which he named Montfort (strong rock, strong castle). Accordingly, from then on he called himself von Montfort . Around the same time he founded the city of Feldkirch with the construction of the Schattenburg . Hugo's sons, Hugo II and Rudolf, shared the paternal inheritance. While Hugo II received the holdings on the right bank of the Rhine and, among other things, Dornbirn, Rudolf split off with his holdings on the left bank of the Rhine and founded his own ancestral seat near Buchs , which was later named von Werdenberg .

Around 1270, the Counts of Montfort split into three lines: Montfort-Feldkirch, Montfort-Bregenz and Montfort-Tettnang. Dornbirn fell again under the influence of the Bregenz count family and remained their subjects until 1338. When the Bregenz line of the Montfort counts died out, Dornbirn came under the rule of Feldkirch together with the rear Bregenzerwald . This change of rule also caused some turbulence in Dornbirn, especially among the upper class. Some of these Dornbirn citizens, led by Johann Huber (Huober) , were committed to joining the Tettnang branch. When Ulrich von Montfort-Feldkirch annexed Dornbirn in 1338, the wealthy citizens had to provide guarantees against fluchsämi (unauthorized moving away). Huber nevertheless went to Count Wilhelm von Montfort-Tettnang, whereupon all his belongings were confiscated. It was not until two years later that an arbitration tribunal lifted these sanctions against Huber.

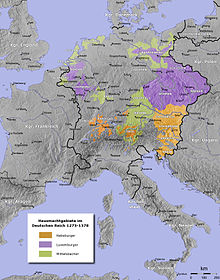

Dornbirn becomes part of the Habsburg Empire

Since the Habsburgs had owned the duchies of Austria and Styria under King Rudolf I in 1278 , they have primarily concentrated on connecting their traditional possessions in the west - in Switzerland , Alsace , in Breisgau and Swabia - with the new territories in the east . The area of today's Vorarlberg and with it the Dornbirn settlement moved into the center of Habsburg interests very soon. In 1337 Rudolf III. and Ulrich II., both from Montfort-Feldkirch, an eternal alliance with the Dukes of Austria, which brought the Montfort-Feldkirch possessions under Habsburg influence over the long term.

In 1363 Duke Rudolf IV was the first Habsburg to gain a foothold in Vorarlberg by buying their castle and rule from the Knights Thumb von Neuburg . At that time, Count Rudolf IV of Montfort-Feldkirch owned the Feldkirch rulership, to which Dornbirn now also belonged. Since three of his four sons died before him, the fourth son - Count Rudolf V, who was Provost of Chur , left the clergy and married Agnes von Mätsch in 1369. After his father's death on March 13, 1375, he succeeded him. On May 22nd of the same year he sold most of his property to Austria for 30,000 guilders . The last installment of this purchase price was paid in 1379.

Therefore, on January 9, 1380, ammen and countrymen of the Bregenzerwald , von Staufen, Langenegg , Dornbirn - including the specially mentioned parcel Knüwen (Knie) - paid homage to their new sovereign, Duke Leopold III. and swore obedience to him. This in turn promised the Dornbirns the indivisibility and unsaleability of the Dornbirn rule. The Dornbirn court invoked this promise in 1655 when it was to be sold to the Emser.

Rule of the Counts of Ems

| (...) I announce to Johann von Sigberg, son of the late Heinrich von Sigberg, (...) that I (...) have sold the honorable knight, Ulrich von Ems and his heirs, truthfully and honestly (.. .) the Mühlebach estate, which is in the parish of Dornbirn, and what goes with it (...)

Excerpt from the translated original text of a deed of purchase from Johann Sigberg from October 16, 1318. |

The Habsburgs let their Feldkirch bailiffs exercise their sovereignty over Dornbirn and all other possessions in the newly acquired Feldkirch domain. In the meantime, the Emsern made a number of important acquisitions in the municipality of Dornbirn. The deed of purchase of Johann Sigberg is historically significant as it represents the first Emsian acquisition of land in Dornbirn. Also on May 21, 1388, knight Ulrich II. Von Ems der Reiche - bought from Weingartner abbot Ludwig Haller the church fee and the widum to Dornbirn for 300 pounds, i.e. the right of patronage over the parish church of St. Martin and the goods belonging to the church's furnishings. On July 20 of the same year, the master and the convent of the Hofen women's monastery near Buchhorn certified the sale of their Dornbirn Kellhof to the knight Ulrich the Younger (this means Ulrich IV - the son of Ulrich II). The purchase price was £ 850 pfennigs . It remains unclear whether at this point in time, as described in the document, court rights were still associated with the Kellhof. A revolt of the people of Dornbirn against the aristocratic manors became clear in the Appenzell Wars, when the Dornbirn natives fought alongside the Appenzeller against the nobility and clergy .

Establishment of the state estates

On August 18, 1391, Count Albrecht III. von Werdenberg-Heiligenberg, Herr zu Bludenz , signed a contract with the Ammann , the council and the citizens of Feldkirch as well as all ammen, courts and citizens in the Feldkirch rulership, to which the Dornbirn settlement also belonged. Bludenz and Feldkirch concluded an alliance for mutual protection for 40 years, which was directed against all possible enemies, with the exception of the dukes of Austria. Historians now regard this peace alliance as the founding document of the Vorarlberg state estates.

Modern times

Witch persecution in Dornbirn

During the economic crisis in the middle of the 16th century, there was an increasing number of judicial persecutions of witches throughout Vorarlberg . These seem to have originated in the Bregenz Forest and then rapidly expanded over the entire Feldkirch rulership and to Bregenz. The outbreak of the wave of witch trials in Dornbirn at the turn of the century was the negotiation against a certain Margareth von Alberschwendi, according to Dornbpeurn . After the Vogt von Feldkirch had the woman tortured for three days in a row without anything being brought against her, the Feldkirch officials turned to the government in Innsbruck to ask how they should proceed. As a result, strict instructions came from Innsbruck to refrain from such careless and unfounded accusations in the future. The Feldkirch officials were also deprived of their independent jurisdiction. The witch trials in the rulers in front of the Arlberg came to an end for the time being.

It was not until the summer of 1563 that another attempt was made to persuade the Feldkirch authorities to initiate a new witch trial. Peter Diem from Dornbirn sued a woman as being responsible for his dwindling livestock. Shortly thereafter, another reprimand was received from Innsbruck that allegations based on superstition should be ignored and, if at all, Peter Diem should be punished. After that, no more talk of witchcraft was heard for a while.

In the autumn of 1585 the first successful witch trial took place in Dornbirn. After an extremely unfavorable economic situation prevailed in those years and Dornbirn was also hit by the plague in 1585, the Dornbirn court reported Ursula Wessin to the Feldkirch authorities. Since the woman had admitted various witchcraft under torture , she was sentenced to death at the stake . Dornbirn experienced the high point of the witch hunt between 1597 and 1605. Dornbirn was the focus of the Vorarlberg witch hunts, so that the Feldkirch authorities in Innsbruck complained about the Dornbirn population because they had demanded numerous witch trials and even seemed ready to lynch justice. This situation drove the people of Feldkirch into a deep crisis, as on the one hand they were pushed to new witch trials by the people of Dornbirn, but on the other hand they were repeatedly admonished by the Innsbruck authorities to intervene against such unlawful accusations and at the same time to negotiate legal accusations as cheaply as possible. This situation saved the lives of many women in Dornbirn.

A sovereign commission found that the ringleader of these unrest in Dornbirn was Peter Rein. The community even turned to Emperor Rudolf II in Prague in their distress . Since caution was now required from the point of view of the authorities, an imperial mandate of November 23, 1598 regarding the legal witch trials was published in Dornbirn at the end of January 1599. The riots and witch trials did not stop until 1605 and even flared up again and again in mass trials. Only when, at the beginning of 1605, Andreas Kalb and his sons were arrested and imprisoned for breaking their original feud, after they had repeatedly accused Jos Wehinger of witchcraft, did the tide of witch persecutions slowly ebb away. Nevertheless, citizens of the "witch's nest" Dornbirn repeatedly came up as witnesses in various witch trials across the country.

The Black Death in Dornbirn

The plague entered Dornbirn in 1585 and later from 1628 to 1630. Since the inheritance law was changed shortly afterwards, it can be assumed that there were significant losses in the population at the time. Dornbirn was badly hit at the end of the 20s of the 17th century. After the Black Death broke out in Ebnit on July 22, 1628 among a crowd of pilgrims who had come pilgrims , it quickly spread to Ems, Dornbirn and Lustenau. According to a note in the year book , the plague in Dornbirn claimed almost 820 deaths from Rochustag (August 16) 1628 to Candlemas (February 2) 1629, which at that time corresponded to over a third of the total population of Dornbirn. The Dornbirn pastor Martin Schmid was among the victims of the plague. In 1629 the plague broke out again, but only claimed 40 lives. The Black Death visited Dornbirn again in 1630 , whereupon it was decided to go to Schwarzach on Sebastianstag (January 20th) . The name of today's Hatlerdorf district is derived from a legend according to which the entire population of Hatlerdorf except for an old woman and a goat without horns, called Hattel, were carried away during the plague of 1628/29. Due to its exposed location, Kehlegg is said to have been spared the epidemic of 1628/29, but was almost depopulated by the Black Death in 1630 or 1635.

The Emser purchase and its repurchase

As early as 1654, the Counts of Ems had bought the court in Dornbirn from Archduke Ferdinand Karl for 12,000 guilders , albeit with the option of repurchasing it within five years. The Dornbirn population put up bitter resistance and refused to pay homage . A saying from that time shows quite clearly what they thought of Emsian rule: "Better Swiss or Swedish, better dead than Emsian." Strangely, however, these words do not come from the Dornbirns themselves, but were held up against them by the Hohenems Count. Supported by the Vorarlberg provincial estates, they offered to raise 4,000 guilders for the repurchase, but asked for confirmation and increase of their privileges. The Archduke then withdrew the sale at the request of Dornbirn and the state estates on July 31, 1655. He rewarded the people of Dornbirn for their loyalty to the Habsburg family by giving the court a new coat of arms, which is still used today as the city coat of arms.

Re-purchase of Ems

In 1759 the last male descendant of the Hohenems family died. Due to the now missing heir, the imperial county of Hohenems fell back to the emperor . Due to difficulties with the owners who now remained with the Emsern, the heiress, Countess Rebekka von Harrach-Hohenems, was soon ready to sell it. Since the Counts of Ems, who were deeply in debt and mostly living abroad, had not played a major role in state politics for decades, this sale was not a special event. As early as 1767, the imperial court had spoken out in favor of the sale of the Emsian property, but the negotiations that followed soon stalled. At the same time as the Dornbirn ransom , the Wolfurter Kellhof and three years later the Widnau-Haslach farm were sold to locals. The negotiations about the acquisition of the Emsian goods and rights to Dornbirner Grund were not a big secret in the community. The council and the community just did not find it advisable to officially inquire about the price.

On October 6, 1771, the baton holder Josef Danner, the clerk Johannes Zumtobel and the administrator of Neuburg, Johann Georg Stauder, were entrusted with the negotiations by the Dornbirn magistrate Johann Kaspar Rhomberg. The signing of the ransom contract on October 30, 1771 was then also expressly carried out by empowered = legitimate court = and community delegates from Dorenbern. They paid 45,250 guilders for all Emsian possessions, spiritual and secular rights, interest and fiefdoms in the Dornbirn court . The purchase only became legally binding after ratification by the emperor. This was postponed due to problems with the sale of other Emsian properties. The treaty of 1771 was not finally confirmed until three years later, on September 13, 1774, by the government of Upper Austria in Freiburg im Breisgau . In the following year, the people of Dornbirn paid the first installment of 15,250 guilders, the remaining amount was raised by November 1776. To this end, 10,000 guilders were borrowed from Graubünden . With this contract, the community itself became lord of 88 families. The ransom of Ems is seen by historians today as a radical change that would bring about industrialization in the following century.

Revolt against Josephine reforms

In 1789 - one year before the death of Josef II - serious unrest broke out in Dornbirn against the emperor's church reforms . The predominantly Catholic citizens of Dornbirn saw their religious practice threatened and became violent. The hatler Löwenwirt Franz Josef Ulmer soon took the lead in this tumult. Above all, the social differences between the urban Niederdorf and the rural and rural Hatlerdorf played a decisive role: While many merchants, landlords and tradesmen welcomed Josef's reforms, they met with deep rejection from the farmers and field workers. The situation escalated in 1791 when the government decided to use the military against the insurgents. Two people were killed while using firearms . The leader of the Dornbirn troublemakers, Franz Josef Ulmer, was arrested and imprisoned in Innsbruck, where he died shortly afterwards. After this unrest, military units were quartered in Dornbirn for a while, but the residents of Dornbirn had to pay for them themselves.

Survey on the market town

In 1793 the municipality of Dornbirn received the right to a weekly market and thus became a market municipality . At this point in time, the young market town was already able to compete with the cities of Vorarlberg in terms of population - including all three, mind you - and even overtook them in the following years. However, the coalition wars against France soon followed , making a weekly market unthinkable for two decades. Only in 1816 did the community apply for a weekly market again. Monday was set as the market day and the city of Bregenz took over the market organization . However, these weekly markets were held sporadically for a long time.

Dornbirn falls to Bavaria

With the Peace of Pressburg , the Austrian Empire under Emperor Franz I had to cede the Counties of Tyrol and Vorarlberg to the Electorate of Bavaria . As a result, the young market town of Dornbirn fell under Bavarian rule in 1805. During this nearly nine-year period under Bavarian rule Dornbirn became the seat of the district court Dornbirn and one of only six more court locations in Vorarlberg, bringing the Bayern set the current judicial district division in Vorarlberg took anticipated. It is also noteworthy that during the relatively short rule of Bavaria, considerations were in the room to divide Dornbirn into four independent communities due to its size. These were supposed to be the four districts of Dornbirn that existed at that time: Niederdorf (today the Markt district), Hatlerdorf, Oberdorf and Haselstauden. The citizens of Dornbirn fought violently against this division. Among other things, it was argued that some parcels had belonged to the parish for over 1000 years, which also made up a single tax district and only had a parish office . The containment of the Dornbirn Oh , it was said, must be carried out jointly by all residents of the valley floor. A few months later, in 1814, Vorarlberg fell back to Austria during the Congress of Vienna and the idea of splitting up the community fizzled out or was hushed up.

Early industrialization and modern politics

With the construction of the first textile factories and the flourishing of the wealthy textile manufacturer families, modern party politics also took hold in Dornbirn. The first large weaving and embroidery mills appeared around 1830 , but the textile industry had already discovered the city as an ideal location. The most important factory owners came from well-to-do families and immediately assumed political functions in Dornbirn. However, actual industrialization did not make its breakthrough until the middle of the 19th century. The first steam engine was purchased by Salmann & Lenz in 1856 . Shortly afterwards, the large companies FM Hämmerle and FM Rhomberg as well as JA Winder were equipped with such machines. By 1894 all of Dornbirn's large textile factories owned steam engines. Although the largest and most important industrial companies in Dornbirn were established before the construction of the railway in 1870, this boosted the development of industry in Vorarlberg again at the end of the 19th century. This industrial boom now also resulted in the formation of wealthy families in Dornbirn, who also had the money and the power to usurp politics in the largest community in the country.

Contemporary history

City elevation in 1901

One of the most important events in the history of Dornbirn is probably the city elevation in 1901 by Emperor Franz Joseph I. Excerpt from the original text of the city elevation diploma: We (...) have found ourselves moved by our imperial and royal power with our resolution of 21 November 1901 To raise our loyal market DORNBIRN in our state Vorarlberg in the most gracious appreciation of its regular community and its significant upswing above the request of the community council to a city.

Simultaneously with the elevation to the city, the emperor allowed the further use of the coat of arms with the pear tree as city coat of arms. The news of the just approved elevation to the city arrived in Dornbirn on December 5th by telegram . It was then arranged that the bells of all parish churches in what is now the city area should be rung. A few days later, the official town elevation celebrations under Mayor Johann Georg Waibel and a torchlight procession with around 1400 participants were held. Dornbirn was the fourth municipality in Vorarlberg to be elevated to the status of a city, and of these four it was the largest city with just under 13,000 inhabitants. And in fact, the reason for the city elevation was probably the "significant upswing" mentioned in the document. This was justified by the construction of the Dornbirn-Lustenau Electric Railway, which had just started, and the arrival of electric light in the Dornbirn factory halls. In addition, Emperor Franz Josef personally put the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy's first out-of-home telephone into operation in Dornbirn . However, the now famous city elevation certificate was not issued until February 28, 1902 in Vienna .

First World War

With the assassination of the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne on June 28, 1914 in Sarajevo , the moment of world politics began that is now referred to as the eve of the First World War . In the following four weeks of July, the citizens of Dornbirn also patriotically pursued the significant steps that ultimately led to the declaration of war on Serbia . Nevertheless, the then mayor of Dornbirn Engelbert Luger had hardly any audience, apart from a few random passers-by, when he read the emperor's manifesto “ To my peoples! “Read. With the general mobilization of July 31st, which was proclaimed and placarded throughout the municipality, 2400 Dornbirn men between the ages of 18 and 42 were finally drafted. In Dornbirn, too , the patriotism on display was only a masquerade that was supposed to conceal the thoughtfulness and concern of the population. The now enlisted Dornbirner up to 35 years served primarily with the four Tyrolean imperial regiments and the three regiments of the Tyrolean state rifle. The 35 to 40 year olds, on the other hand, were assigned to the Tyrolean Landsturm Regiments 1 and 2. Contrary to the expectations of the population, however, the soldiers assigned to the Landsturm were soon deployed on the war fronts . Of the 2,400 Dornbirn natives who had entered the war, 87 fell victim to the war in the first year of the war, and 22 were reported missing.

Thus in 1914 there were two more, and in the following year as many as eight follow-up inspections , in which even the 50-year-old men were still tested for their fitness. In May 1915, because of the looming war against Italy and the associated southern front, the “last contingent” was mobilized, the Standschützen. The Dornbirn Standschützen - out of a total of 630 men, 245 were directly from Dornbirn - solemnly left their hometown on May 23, 1915, the day Italy declared war . At the beginning of 1916 there were already around 3,000 people from Dornbirn on the various battlefields, a year later there were 4,000, which corresponded to a quarter of the total population of the city raised in peacetime. A total of 596 soldiers from Dornbirn died in the course of the First World War. 157 men died in combat, 287 died in hospitals , 72 died after the war ended and 80 are missing.

Interwar period

In the years following the Great War , the poor overall economic situation also affected the living conditions of the population in Dornbirn. Jobs , money and food were scarce and the mood was generally bad. Nevertheless, like all of Western Austria , Dornbirn was largely spared the general political confusion of the 1920s and the civil war unrest. The Christian Socialists, who were already very strong before the war, were the determining political power in Dornbirn in the years of the First Republic and also provided all of the city's mayors during this period . The citizens were open or even warm to any new political direction as long as it promised an improvement in the current economic situation. Even before Austria was annexed to the German Reich , Dornbirn was known as the “brown nest” in Vorarlberg due to the high number of self-confessed National Socialists . The number of National Socialists in Dornbirn before the ban on the NSDAP in Austria on June 19, 1933 is estimated today at around 600 to 800 people, with the wealthier industrialists in particular supporting the National Socialists.

Dornbirn's reputation as a brown nest was clearly evident when Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss visited on June 29, 1933, when he was walking through the city under military guard and shouting “ Heil Hitler ”. Ultimately, after a brief address in the cattle market hall, the Chancellor had to leave the city through a side street for his own safety. Between July 5th and 31st, 27 people from Dornbirn were arrested for political activity, which was an absolute record in Vorarlberg. In the months that followed, Dornbirn experienced a hitherto unknown wave of terror. Small bomb attacks and swastika smearings were carried out several times. Over 500 people from Dornbirn were sentenced to a total of more than 25,000 days in prison, and the 9th Company of Infantry Regiment No. 5 was transferred from Krems to Dornbirn.

Period of National Socialism and World War II

On March 12, 1938, after Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg's abdication, the day before, troops of the German Wehrmacht marched into Dornbirn to the general cheer of the population. Anton Plankensteiner immediately moved from Dornbirn to Bregenz as the new Gauleiter to remove Governor Ernst Winsauer from his office. In the referendum on the connection of Austria to the German Reich on April 10, 1938, which took place just under a month later, 98.57% of the voters in Dornbirn voted for the connection. Only 144 people voted against, 22 voted invalid and another 14 abstained.

Shortly afterwards the deportations of political opponents and Jews to the Dachau concentration camp began , including the Turteltaub family, the only Jewish family in Dornbirn. The Dornbirn gendarmerie post commander Hugo Lunardon played a decisive role in the fight against the Nazis, who were previously illegal. After the Nazis came to power, he was immediately arrested and transported to the Mauthausen concentration camp, where he was killed on March 14, 1940. Chaplain Carl Lampert , who was beatified in the Dornbirn parish church of St. Martin in 2011 and who worked as a young priest in Dornbirn, was arrested by the National Socialists and executed on November 13, 1944.

During the time of National Socialism in Austria , Dornbirn was next to Bregenz and Bludenz one of the three Vorarlberg district towns in the Reichsgau Tirol-Vorarlberg . During the Second World War , a total of 5,789 men from Dornbirn did military service, some of them voluntarily, some of which were compulsory, and most of them were deployed in the German armed forces. At least 716 of the Dornbirn soldiers died, according to other sources up to 1000.

literature

- Werner Matt, Hanno Platzgummer (ed.): History of the city of Dornbirn . Verlag Stadt Dornbirn, City Archives and City Museum, Dornbirn 2002, ISBN 3-901900-11-X .

- Ingrid Böhler: Dornbirn in wars and crises: 1914 - 1945 . Studienverlag , Innsbruck 2005. ISBN 3-7065-1974-7 .

- Werner Matt: History of Dornbirn . ISBN 978-3-901900-37-2 . In: Office of the City of Dornbirn (Ed.): Dornbirn Portrait . Dornbirn, 2012, ISBN 978-3-901900-46-4 .

- Werner Bundschuh , Harald Walser (Ed.): Dornbirner Statt-Histories. Vorarlberger Authors Society, Bregenz 1987, ISBN 3-900754-00-4 .

Web links

- History of the city in the Dornbirn Lexicon of the Dornbirn City Archives .

- Dornbirn history workshop

Individual evidence

- ↑ Statistics Austria - Population at the beginning of 2002–2020 by municipalities (area status 01/01/2020)

- ↑ Manfred Tschaikner : "So that evil may be exterminated" witch hunts in Vorarlberg in the 16th and 17th centuries. Vorarlberger Authors Society , Bregenz, 1992, ISBN 3-900754-12-8 .

- ↑ The ransom of Dornbirn von Ems - the cause of the rise since 1771 . In: Vorarlberger Verlagsanstalt (Hrsg.): Montfort - Quarterly magazine for history and contemporary studies of Vorarlberg . 23rd year 1971 / issue 3.

- ↑ a b c Werner Matt, Hanno Platzgummer (ed.): History of the city of Dornbirn . 2002, p. 135.

- ↑ Werner Matt, Hanno Platzgummer (ed.): History of the city of Dornbirn . 2002, p. 134.

- ↑ Markus Barnay: Vorarlberg - From the First World War to the present . Haymon Verlag , Innsbruck 2011, ISBN 978-3-85218-861-4 .

- ↑ Werner Matt, Hanno Platzgummer (ed.): History of the city of Dornbirn . 2002, p. 193 ff.

- ↑ Werner Matt, Hanno Platzgummer (ed.): History of the city of Dornbirn . 2002, p. 207.

- ↑ Harald Walser : The death of a state servant. Hugo Lunardon and National Socialism in Dornbirn. In: Werner Bundschuh / Harald Walser (eds.): Dornbirner Statt stories. Bregenz 1987, ISBN 3-900754-00-4 .

- ↑ Richard Gohm (Ed.): Blessed are those who are persecuted for my sake. Carl Lampert - a victim of Nazi arbitrariness 1894–1944 . Tyrolia, Innsbruck 2008.

- ^ Ingrid Böhler: Dornbirn in wars and crises: 1914 - 1945 . Studienverlag , Innsbruck 2005. ISBN 3-7065-1974-7 .

- ^ Wolfgang Weber , Franz Mathis: Vorarlberg. Between Fußach and Flint, Alemannicism and cosmopolitanism. Series of publications by the Research Institute for Political-Historical Studies of the Dr.-Wilfried-Haslauer-Bibliothek 6/4, Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-205-98701-2 , p. 55.