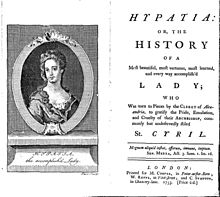

Hypatia

Hypatia (also Hypatia of Alexandria , Greek Ὑπατία Hypatía ; * around 355 in Alexandria ; † March 415 or March 416 in Alexandria) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer and philosopher in late antiquity . Nothing of their work has survived, and details of their teaching are not known. She taught publicly and represented a neo-Platonism, presumably enriched with Cynical ideas . As a representative of a non-Christian philosophical tradition, she belonged to the oppressed pagan minority in the predominantly Christian Alexandria . Nevertheless, she was able to teach unchallenged for a long time and enjoyed a high reputation. In the end, however, she became the victim of a political power struggle in which the church doctor Kyrill of Alexandria instrumentalized religious differences. An incited mob of lay Christian brothers and monks eventually took them to a church and murdered them there. The body was dismembered.

Posterity will remember Hypatia mainly for the spectacular circumstances of her murder. Since the 18th century, the case of pagan persecution has often been cited by critics of the Church as an example of intolerance and hostility towards science. From a feminist point of view, the philosopher appears as an early representative of an emancipated femininity, equipped with superior knowledge, and as a victim of the misogynistic attitude of her opponents. Modern non-scientific representations and fictional adaptations of the material paint a picture that adorns the sparse ancient tradition and, in some cases, greatly modifies it.

Even before Hypatia there was a woman who according to the testimony of Pappos taught in Alexandria mathematics, Pandroseum .

swell

Little is known about Hypatia's life and work. The main sources are:

- seven letters addressed to Hypatia by the Neo-Platonist Synesius of Cyrene , who also mentions them in other letters and in his treatise On the Gift . As a student and friend of Hypatias, Synesios was very well informed. Since he adhered to Neoplatonism, but was also a Christian and even became bishop of Ptolemais , his view is relatively little shaped by taking sides in religious conflicts.

- the church history of Socrates of Constantinople ( Sokrates Scholastikos ), who was a younger contemporary of Hypatias. Regardless of the religious contrast, Socrates portrayed the philosopher respectfully and emphatically condemned her murder as an unchristian act. Most of the representations by later Byzantine historians are based on his information , but some of them assess the events differently than Socrates.

- the philosophical history of the Neoplatonist Damascius , which has only survived in fragments and was written in the period 517-526. Damascius was a staunch supporter of the ancient religion and opponent of Christianity. Nevertheless, he was inclined to make critical judgments about the competence of Neoplatonic philosophers who did not meet his own standards, and his remarks about Hypatia also reveal a derogatory attitude.

- the chronicle of the Egyptian bishop John of Nikiu . John, who writes in the 7th century, that is, reports from a great distance in time, approves of Hypatia's murder and unreservedly takes sides with her radical opponents.

- article dedicated to Hypatia in Suda , a 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia. There, information of different origins and quality are uncritically strung together. The author of the Suda article used news material from the philosophical history of Damascius and probably also from another late antique source, the collection of literary biographies compiled by Hesychios of Miletus , which today has been lost except for fragments. Legendary decoration can be seen in its representation.

Life

Hypatia's father was the astronomer and mathematician Theon of Alexandria , the last scientist known by name at the Museion of Alexandria , a famous state-funded research facility. Hypatia was probably born around 355, because at the time of her death, as the chronicler Johannes Malalas reports, she was already an "old woman", probably around sixty years old. She seems to have lived in her hometown of Alexandria all her life. She received a mathematical and astronomical education from her father. Later she took part in his astronomical work. It is not known who her philosophy teacher was; According to a research hypothesis, Antoninos, a son of the philosopher Sosipatra , comes into consideration.

After completing her education, she began teaching math and philosophy herself. According to Suda, she combined a talent for rhetoric with a prudent, well-considered approach. Socrates of Constantinople reports that listeners came to her from everywhere. Some of her students were Christians. The most famous of them was Synesios, who studied both philosophy and astronomy with her in the last decade of the 4th century. Damascius reports that Hypatia wore the philosopher's coat (tríbōn) and was out and about in the city to teach publicly and to interpret the teachings of Plato or Aristotle or any other philosopher to anyone who wanted to hear her . How this message is to be interpreted is controversial in research. In any event, it does not support the view that Hypatia held a publicly funded chair; there is no evidence of this. Étienne Évrard interprets the formulation of Damascius in the sense of a lesson on the street. The traditional portrayal of Hypatia's teaching method brings the philosopher outwardly closer to cynicism , as does the reference to her philosopher's coat, a garment that was used to associate with Cynics.

Damascius suggests that he disapproved of Hypatia's public appearance. He was of the opinion that philosophy classes should not be given in public and not to everyone, but only to appropriately qualified students. He may have exaggerated in his portrayal of Hypatia's work. In any case, one can infer from his words that they presented philosophical topics that were otherwise used to discuss in a closed circle among appropriately educated people to a relatively broad public.

An anecdote handed down in the Suda points in this direction, according to which she showed a student who was in love with her menstrual blood as a symbol for the impurity of the material world in order to make him drastically aware of the dubiousness of his sexual desire. Disdain for the body and physical needs was a feature of the Neoplatonic worldview. Even if the anecdote may have only originated in the course of the legendary formation, it may have a real core; in any case, Hypatia was known not to shy away from deliberately provocative behavior. This is also an indication of a Cynical element in their philosophical attitude: Cynics used to shock calculated in order to produce knowledge.

In addition to the subject matter that Hypatia conveyed to the public, there were also secret teachings that were to be reserved for a smaller group of students. This can be seen from the correspondence of Synesios, who repeatedly reminded his friend and classmate Herculianos of the commandment of secrecy (echemythía) and accused Herculianos of not having observed it. Synesios refers to the Pythagorean command of silence ; The transfer of secret knowledge to unqualified people leads to such vain and incomprehensible listeners for their part passing on what they have heard in a distorted form, which ultimately causes the public to discredit philosophy.

Socrates of Constantinople writes that Hypatia performed in the vicinity of high officials. What is certain is that it belonged to the circle of the Roman prefect Orestes .

Hypatia remained unmarried all of her life. The statement in the Suda that she was married to a philosopher named Isidorus is due to an error. Damascius mentions its extraordinary beauty.

As part of her scientific work, Hypatia also dealt with measuring devices. This can be seen from Synesios's letter request that she send him a “hydroscope”, which apparently meant a hydrometer . Whether the instrument for recording and describing the movements of the celestial bodies, which Synesios had built, was constructed according to Hypatia's instructions, is disputed in research.

death

Hypatia was murdered in March 415 or March 416. The prehistory formed a primarily political and personal conflict with religious aspects, with which it probably originally had nothing to do.

prehistory

Already in the second half of the 4th century there had been strong tensions in Alexandria between parts of the Christian population and followers of the old cults, which led to violent riots with fatalities. In the course of these conflicts, the minority was increasingly pushed back. The Patriarch Theophilos of Alexandria had places of worship destroyed, in particular the famous Serapeum , but the pagan teaching was only temporarily impaired, if at all.

The religious-philosophical worldview of the educated who clung to the old religion was a syncretistic Neo-Platonism, which also integrated parts of Aristotelianism and stoic thoughts into its worldview. These pagan Neoplatonists tried to bridge the differences in the traditional philosophical systems through a coherent synthesis of the philosophical traditions, and thus strived for a unified teaching as a philosophical and religious truth par excellence. The only exception to the synthesis was Epicureanism , which the Neo-Platonists rejected altogether and did not regard as a legitimate variant of Greek philosophy.

Between pagan Neoplatonism and Christianity there was a substantive contrast that was difficult to bridge. Only Synesius, who was both a Christian and a Neoplatonist, tried to harmonize it. In matters of conflict, however, he ultimately gave preference to Platonic philosophy over doctrines. The religiously oriented non-Christian Platonists, who created the spiritual basis for the continued existence of Pagan religiosity in educated circles, appeared to Christians as prominent and stubborn opponents.

People from this pagan milieu did not become victims of persecution and displacement because of their adherence to their religious-philosophical worldview - for example, when conveying conventional educational content to schoolchildren - but because of their cult practice. Since Iamblichos of Chalkis , many Neoplatonists have valued and practiced theurgy , a ritual contact with the gods for the purpose of interacting with them. From a Christian point of view, this was sorcery, idol worship and the conjuring of devilish demons. Radical Christians were not ready to condone such practices, especially since they assumed that it was a malicious use of magic powers.

In addition to the conflicts between pagan and Christian inhabitants of Alexandria, there were also serious rifts among Christians between supporters of different theological schools and disputes between Jews and Christians. This mixed political contradictions and power struggles, the background of which also included personal enmities.

The starting point of the events that ultimately led to Hypatia's death were physical clashes between Jews and Christians, which escalated and claimed numerous lives. The Patriarch Cyril of Alexandria , who had been in office since October 412, was the nephew and successor of Theophilos, whose course of religious militancy he continued. At the beginning of his term in office, Kyrill made a name for himself as a radical opponent of the Jews. An agitator by the name of Hierax, who was active in his sense, stirred up religious hatred. When he appeared in the theater at an event by Prefect Orestes, the Jews present accused him of having only come to stir up a riot. Orestes, who was a Christian but, as the highest representative of the state, had to ensure internal peace, had Hierax arrested and immediately questioned publicly under torture. Thereupon Kyrill threatened the leaders of the Jews. After a night attack by the Jews, who had killed many Christians, Kyrill organized a comprehensive counter-attack. His followers destroyed the synagogues and looted the houses of the Jews. Jewish residents were expropriated and driven from the city. The assertion of Socrates of Constantinople that all Jews living in Alexandria were affected seems, however, to be exaggerated. There was also a Jewish community in Alexandria later. Some of the displaced returned.

Johannes von Nikiu, who describes the events from the perspective of the patriarch's supporters, accuses Orestes of taking sides with the Jews. They were ready to attack and massacre Christians because they could have counted on the support of the prefect.

The unauthorized action of the patriarch against the Jews challenged the authority of the prefect, especially since attacks on synagogues were prohibited by law. There was a bitter power struggle between the two men, the highest representatives of the state and the Church in Alexandria. In doing so, Kyrill relied on his militia (the Parabolani ). Around five hundred violent monks from the desert arrived to reinforce his followers. Kyrill had excellent relations with these militant monks, having lived among them for a number of years earlier. In the milieu of the partly illiterate monks there was an attitude hostile to education and radical intolerance towards everything non-Christian; they had already actively supported the Patriarch Theophilos in the persecution of religious minorities. The patriarch's supporters claimed that the prefect protected opponents of Christianity because he sympathized with them and was secretly a pagan himself. The fanatical monks openly confronted the prefect while he was out and about in the city and challenged him with insults. A monk named Ammonios injured Orestes by throwing a stone in the head. Then almost all of the prefect's companions fled, so that he found himself in a life-threatening situation. He owed his salvation to the rushing citizens who chased away the monks and captured Ammonius. The prisoner was interrogated and died under torture. Thereupon Cyril publicly praised the courage of Ammonius, gave him the name "the admirable" and wanted to introduce a martyr cult for him. However, this hardly met with approval from the Christian public, as the actual course of the dispute was all too well known.

assassination

Now Kyrill or someone close to him decided to take action against Hypatia, which was suitable as a target because she was a prominent pagan personality in the immediate vicinity of the prefect. According to the report of Socrates of Constantinople, the most credible source, the rumor was spread that Hypatia, as adviser to Orestes, encouraged Orestes to adopt an unyielding attitude and thus thwart a reconciliation between the spiritual and secular violence in the city. Incited by this, a crowd of Christian fanatics gathered under the leadership of a certain Petros, who held the rank of lecturer in the church , and ambushed Hypatia. The Christians took possession of the old philosopher, brought her to the church Kaisarion, stripped her there naked and killed her with “broken pieces” (another meaning of the word ostraka used in this context is “roof tile”). Then they tore the body to pieces, took its parts to a place called Kinaron, and burned them there.

Johannes von Nikiu presents a version that largely corresponds to that of Socrates in terms of the sequence and only differs slightly in detail. According to his account, Hypatia was brought to the church Kaisarion, but not killed there, but dragged to death naked in the streets of the city. The result was a solidarity between the Christian population and the patriarch, since he had now wiped out the last remnants of paganism in the city. John of Nikiu, whose report appears to reflect the official position of the Church of Alexandria, justifies the murder by claiming that Hypatia seduced the prefect and the city population using satanic sorcery. Under their influence, the prefect no longer attended the service. John describes the editor Petros, the direct instigator of the murder, as an exemplary Christian.

The description of the prehistory of Damascius is hardly credible, who claims that when Kyrill happened to be driving past Hypatia's house, he noticed a crowd that had gathered in front of it, and then decided to get rid of them out of envy of Hypatia's popularity.

For Orestes the murder meant a spectacular defeat and he lost a lot of prestige in the city, as he could neither protect the philosopher who was friends with him nor punish the perpetrators. Lawsuits were brought against the murderers, but without consequences. Damascius claims judges and witnesses were bribed. An embassy from the patriarch went to Constantinople to the court of the Eastern Roman emperor Theodosius II to describe the events from the perspective of Cyril. A little later, however, a year and a half after Hypatia's death, the patriarch's opponents were able to deal a severe blow to him because they succeeded in asserting themselves in Constantinople. Imperial ordinances of September and October 416 stipulated that in future embassies to the emperor would no longer be allowed, bypassing the prefect, and that the patriarch's militia would be reduced and henceforth placed under the control of the prefect. Accordingly, this troop lost the character of a militia that the patriarch could use at will and even use against the prefect. However, these imperial measures did not last long, as early as 418 Kyrill was able to regain command over his militia.

The question of whether the patriarch Kyrill instigated or at least condoned the murder has long been controversial. A clear clarification is hardly possible. In any case, it can be assumed that the perpetrators could assume that they were acting in the interests of the patriarch.

Edward Watts doubts that Petros planned Hypatia's death. Watts points out that in late antiquity there were often confrontations between prominent personalities and an angry mob, but this rarely pursued a killing intention. Targeted killings were rare even in Alexandria, where riots were frequent; it had happened twice in the 4th and 5th centuries, and both times (361 and 457) the victims were unpopular bishops. It is also possible that Petros tried to intimidate the old philosopher into withdrawing from her advisory role with Orestes, but then the situation got out of hand.

Works and teaching

Damascius' representation that Hypatia interpreted both the writings of Plato and Aristotle and generally lectured on any philosopher, shows her as a representative of the syncretism prevailing at her time. It was based on a fundamentally uniform doctrine of all philosophical directions that were considered serious at the time. The various directions, with the exception of the despised Epicureanism, were brought together under the roof of Neoplatonism. More recent research no longer doubts that Hypatia was a Neoplatonist. Socrates of Constantinople explicitly states that she belonged to the school that Plotinus founded, and that this was the Neoplatonic. The hypothesis of John M. Rist, according to which Hypatia represented a pre-Neoplatonic philosophy linked to Middle Platonism , did not gain acceptance.

The question of which direction of Neoplatonism Hypatia belonged to is answered differently in research. Since the sources do not convey anything, only hypothetical considerations are possible. According to one assumption, the philosopher placed herself in the tradition of Iamblichus and practiced theurgy accordingly. According to the opposite opinion, it belonged more to the direction of Plotinus and Porphyry , who postulated a redemption of the soul through its own strength through spiritual striving for knowledge.

In the Suda, several works - all mathematical or astronomical in content - are ascribed to her: a commentary on the arithmetic of Diophantos of Alexandria , a commentary on the conic sections of Apollonios von Perge and a text entitled "Astronomical Canon" or "On the Astronomical Canon" . It is unclear whether the latter work was a commentary on the "Handy Tafeln" of the astronomer Ptolemaios , as is usually assumed, or Hypatias' own table work. These writings probably went under early because they are not mentioned anywhere else.

There is not a single concrete mathematical, scientific or philosophical statement passed down that can be ascribed to Hypatia with certainty. However, in the oldest manuscript of the commentary he wrote on Ptolemy's Almagest , her father Theon noted in the title of the third book that it was "a version reviewed by the philosopher Hypatia, my daughter". It is unclear whether this means that she checked the text of the Almagest manuscript, which Theon used to create his commentary, for errors, or whether she intervened in the text of Theon's comment. Traces of a revision can be seen in the comment, which may indicate that she was really involved in this work by her father. However, this can also involve interventions by another, perhaps much later processor.

Assumptions about other works that Hypatia could have written are speculative, as are attempts to find traces of her commenting or editing activity in the traditional texts of the Arithmetic of Diophantos and other works.

reception

Ancient and Middle Ages

Hypatia already enjoyed a legendary reputation during her lifetime. Synesios extolled her and mentioned her great influence in a letter addressed to her, which made her an important factor in public life. Socrates Scholastikos wrote in his church history that she had surpassed the philosophers of her time and was generally admired for her virtue. That she was extremely venerated in Alexandria is also testified by a report handed down by the Suda. Therefore her murder caused a sensation and was condemned by some of the Christian historians. The Arian church historian Philostorgios took the opportunity to hold his theological opponents, the supporters of the Council of Nicaea, responsible for the murder. The process was also known in the Latin-speaking West: a chapter of the church history Historia ecclesiastica tripartita , compiled under Cassiodor's direction , is dedicated to the fate of Hypatias. This version follows the representation of Socrates of Constantinople, but deviates from his report, states that the philosopher was killed with stones.

The poet Palladas is traditionally attributed a poem of praise to Hypatia, of which five verses have been passed down in the Anthologia Palatina . Alan Cameron argues against this ascription and says that the poet was an unknown Christian and that Hypatia, whom he glorified, was not the philosopher, but probably a nun . Enrico Livrea disagrees; he considers the poem to be Hypatia's epitaph. Kevin Wilkinson says Palladas died before the middle of the 4th century; He considers the questions of the authorship of the praise and the identity of the praised woman to be completely open.

The report by John of Nikiu from the 7th century, which justifies the murder, is probably based on a lost late antique depiction, and reflects the point of view of Hypatia's ecclesiastical enemies. In it, she appears as a criminal magician who has brought serious harm to the city using magic spells . Therefore, she had to be killed, as a punishment for her crimes as well as to protect the residents. John belonged to the Coptic Church , which counted Hypatia's opponent Kyrill among its most important saints and did not consider the possibility of wrongdoing by this church father.

According to recent research, the hagiographic representation of the personality and fate of Catherine of Alexandria, venerated as a saint and martyr , was largely constructed from elements of the Hypatia tradition. It is believed that Catherine, allegedly executed in 305, is an invented figure. Their cult is attested from the 7th century. It is possible that a report on Hypatia provided part of the material when the Catherine legend was formed, whereby the roles of Christians and pagans were reversed.

In the 14th century, the Byzantine historian Nikephoros Gregoras reported that the Empress Eudokia Makrembolitissa , who lived in the 11th century, was called "a second Theano and Hypatia". From his words it can be seen that Hypatia lived on in the medieval Byzantine Empire as the model of an excellently educated woman.

Early modern age

In 1690, Gilles Ménage published his Historia mulierum philosopharum ("History of Women Philosophers"), in which he compiled sources on Hypatia's life and death. The instrumentalization of the topic for religious and philosophical polemics began in the late 17th century. The Protestant church historian Gottfried Arnold judged the role of the patriarch to be criminal in his Unparty Church and Heretic History (first printed in 1699). In the 18th century, the fate of Hypatias was thematized from the point of view of the contrasts between Catholics and Protestants as well as between representatives of the Enlightenment and the Catholic Church. In 1720 the Irish philosopher John Toland , a Deist who had left the Catholic Church, published his anti-church work Tetradymus , which also contained an essay entitled Hypatia , in which he idealized the philosopher and made Cyril fully responsible for the murder. Henry Fielding also referred to Hypatia's fate in his anti-church satire A journey from this world to the next (1743). Her death was considered a striking example of a church-sponsored hand murderous fanaticism particular reconnaissance as Voltaire denounced. Voltaire commented on this, among other things, in his exam important de Milord Bolingbroke ou le tombeau du fanaticisme . For him, Hypatia was a precursor of the Enlightenment that had been eliminated from the clergy. The historian Edward Gibbon had no doubt about Kyrill's responsibility for the murder; he saw in Hypatia's elimination a prime example of his interpretation of late antiquity as an epoch of decay of civilization, which he associated with the rise of Christianity.

Kyrill's guilt was denied or downplayed by Christians with a strong ecclesiastical orientation. The Anglican Thomas Lewis published a pamphlet in 1721 in which he defended Kyrill against Toland's polemics and described Hypatia as the “most impudent school mistress”. The justification of Cyril was also the aim of a treatise published in 1727 by the French Jansenist Claude-Pierre Goujet. Even among the Protestant scholars in Germany, Kyrill found a zealous defender: Ernst Friedrich Wernsdorf denied in a study published in 1747-48 that the patriarch was responsible for the murder.

Modern

Classical Studies and Feminism

An assessment of Hypatia's philosophical, mathematical and astronomical achievements is speculative and problematic in view of the very unfavorable source situation. Christian Lacombrade emphasizes that Hypatia owes her fame to the circumstances of her death, not her life's work. A counter-position to this skeptical assessment of its importance can be found in feminist research, where Henriette Harich-Schwarzbauer in particular, with her habilitation thesis Hypatia von Alexandria, presented in Graz in 1997 . Profiled the testimony to the Alexandrian philosopher . In the feminist discourse, the ancient texts on Hypatia are interpreted from the perspective of gender research . Her fate appears as an example of "how to deal with female intellectuality and how to deal with female authorship". Just as Hypatia's corpse was dismembered, her life's work was also dismembered by tradition. "Surrendering them to oblivion was a calculation."

Philostorgius' statement that Hypatia far surpassed her father in mathematics and astronomy provides an indication of the opinion held in modern scientific and non-scientific literature that she was a leader in these fields in her day. With the emphasis on their scientific qualifications, some modern judges associate the view that their death marks a historic turning point: the end of ancient mathematics and natural science and, in particular, the participation of women in scientific endeavors.

In 1925, Dora Russell , wife of the philosopher Bertrand Russell , published as Mrs. Bertrand Russell a feminist pamphlet called Hypatia or Woman and Knowledge .

Several feminist magazines have been named after the late antique philosopher: Hypatia. Feminist Studies was founded in Athens in 1984; Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy has been published in Bloomington, Indiana since 1986. In Berlin there was the magazine Hypatia from 1991 to 1998 . Discussion of historical women's studies .

Fiction, music, visual arts and film

Modern fiction took up the material and popularized it, poets and writers took up the historical theme and alienated the material in some cases considerably. Charles Leconte de Lisle wrote two versions of a Hypatia poem, which found many readers in the second half of the 19th century, and the short drama Hypatie et Cyrille (1857). He glorified the ideal of a combination of wisdom and beauty that he saw realized in Hypatia. The writer Charles Kingsley achieved the strongest and most lasting effect with his novel Hypatia or New Foes with an Old Face , published in London in 1853 and first published in German in 1858. This novel made Hypatia known to a wide audience. Kingsley treated the material from a Christian but anti-Catholic perspective. Although he painted a generally positive picture of Hypatia, he presented her philosophical way of life as a wrong path. His declared aim was to present Christianity as "the only truly democratic belief" and philosophy as "the most exclusive aristocratic belief". For him, too, the combination of wisdom and beauty is what makes Hypatias so fascinating. Kingsley's design of the fabric formed the basis for Arnold Beer's tragedy Hypatia , a tragedy in verse , published in 1878 . In 1906 Hans von Schubert stated: "Kingsley's Hypatia has long since become the common property of the educated public, a favorite book especially of the historically educated public, including in Germany." Fritz Mauthner wrote a church-critical novel Hypatia (1892).

The opera Hypatia , an azione lirica in three acts, was written by the composer Roffredo Caetani and was published in 1924 and premiered in 1926 at the German National Theater in Weimar. It is about the last day of Hypatias' life. The Italian writer Mario Luzi wrote the drama Libro di Ipazia (1978), in which he thematized the inevitability of the end of the world represented by Hypatia. In 1987 the story Renaissance en Paganie by the Québec- born politician and writer Andrée Ferretti appeared, in which Hypatia plays an important role. In 1989 the Canadian medievalist and writer Jean-Marcel Paquette published the novel Hypatie ou la fin des dieux ("Hypatia or The End of the Gods") under his pseudonym Jean Marcel . In 1988 the youth book author Arnulf Zitelmann published his historical novel Hypatia , in which Hypatia is confronted with the patriarch Kyrill as a champion of free thinking and responsible action.

Hypatia found its way into the visual arts of the 20th century: the feminist artist Judy Chicago dedicated one of the 39 place settings to her in The Dinner Party .

In 2000 the novel Baudolino by Umberto Eco was published . The title character encounters a hybrid creature who connects the upper body of a woman with a goat-shaped body from the belly down and introduces himself as “a Hypatia”. According to her report, she is one of the descendants of students of the philosopher Hypatia who fled after the murder. They all have the name Hypatia. They received the shape of hybrid beings because they reproduce with satyrs . They profess a doctrine of salvation shaped by Gnostic ideas, which they oppose to the Christian doctrine.

In 2009, the director Alejandro Amenábar shot the feature film Agora - The Pillars of Heaven with Rachel Weisz in the lead role through Hypatia . Hypatia is an important astronomer there. Like Aristarchus, she represents a heliocentric worldview and even discovers the elliptical character of the earth's orbit, thereby partially anticipating an early modern model. With her scientific way of thinking she arouses offense in fundamentalist religious circles. Whether the film offers a realistic depiction of the protagonist and the conditions in Alexandria in late antiquity is disputed. According to the director, this is the case. The historian Maria Dzielska, on the other hand, thinks that the film has “little to do with the authentic, historical Hypatia”.

Designations

The asteroid (238) Hypatia is named after Hypatia and was discovered on July 1, 1884 by Viktor Knorre at the Berlin observatory . The lunar crater Hypatia also bears her name. To the north of the crater there are lunar grooves called Rimae Hypatia ("Hypatia grooves"). In 2015 the exoplanet Hypatia ( Iota Draconis b ) was named after Hypatia after an IAU public competition .

Source collection

- Henriette Harich-Schwarzbauer : Hypatia. The late antique sources (= Sapheneia. Volume 16). Peter Lang, Bern et al. 2011, ISBN 978-3-0343-0699-7 (habilitation thesis in a revised version; source texts with introduction, translation and commentary; review at sehepunkte )

literature

Overview representations, manuals

- Henriette Harich-Schwarzbauer : Hypatia. In: Christoph Riedweg et al. (Ed.): Philosophy of the Imperial Era and Late Antiquity (= Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 5/3). Schwabe, Basel 2018, ISBN 978-3-7965-3700-4 , pp. 1892–1898, 2131 f.

- Christian Lacombrade: Hypatia. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 16, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-7772-5006-6 , Sp. 956-967.

- Silvia Ronchey : Hypatia the Intellectual. In: Augusto Fraschetti (Ed.): Roman Women. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2001, ISBN 0-226-26094-1 , pp. 160-189, 227-235.

- Henri Dominique Saffrey: Hypatie d'Alexandrie. In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques. Volume 3, CNRS Éditions, Paris 2000, ISBN 2-271-05748-5 , pp. 814-817.

Monographs, studies

- Michael AB Deakin: Hypatia of Alexandria. Mathematician and Martyr. Prometheus Books, Amherst (New York) 2007, ISBN 978-1-59102-520-7 .

- Maria Dzielska: Hypatia of Alexandria. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1995, ISBN 0-674-43775-6 .

- Silvia Ronchey: Ipazia. La vera storia. Rizzoli, Milano 2010, ISBN 978-88-17-0509-75

- Edward J. Watts: Hypatia. The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017, ISBN 978-0-19-021003-8 .

reception

- Véronique Gély: Hypatia. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 525-534.

Web links

- Literature by and about Hypatia in the catalog of the German National Library

- Texts on Hypatia (English)

- Synesios of Cyrene, Letter 154 to Hypatia, English ( Memento from June 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Johannes von Nikiu, Chronicle 84.87-103 (English)

Remarks

- ↑ Suda, Adler -Nr. Y 166, online .

- ^ The hypothesis of Denis Roques, according to which the father Hypatias was really called Theoteknos, did not prevail; see Henri Dominique Saffrey: Hypatie d'Alexandrie . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 3, Paris 2000, pp. 814–817, here: 814.

- ↑ See Henri Dominique Saffrey: Hypatie d'Alexandrie . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 3, Paris 2000, pp. 814–817, here: 814 f. and Robert J. Penella: When was Hypatia born? In: Historia 33, 1984, pp. 126–128 with further arguments; see. Michael AB Deakin: Hypatia of Alexandria, Mathematician and Martyr , Amherst (New York) 2007, p. 51 f., 174 and Maria Dzielska: Hypatia of Alexandria , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1995, p. 67 f. The old dating approach around 370 is outdated.

- ^ Alan Cameron, Jacqueline Long: Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius , Berkeley 1993, p. 51; Henri Dominique Saffrey: Hypatie d'Alexandrie . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 3, Paris 2000, pp. 814–817, here: 816.

- ↑ Heinrich Dörrie , Matthias Baltes : Platonism in antiquity , Volume 3, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1993, p. 133, note 6; Edward J. Watts: City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria , Berkeley 2006, pp. 194 f .; Maria Dzielska: Hypatia of Alexandria , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1995, p. 56. Markus Vinzent represent the hypothesis of a state-paid teaching activity by Hypatia: “Oxbridge” in late antiquity . In: Zeitschrift für antikes Christianentum 4, 2000, pp. 49–82, here: 67–69 and Pierre Chuvin : Chronique des derniers païens , Paris 1991, p. 90.

- ↑ Étienne Évrard: À quel titre Hypatie enseigna-t-elle la philosophie? In: Revue des Études grecques 90, 1977, pp. 69–74.

- ↑ See Alan Cameron, Jacqueline Long: Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius , Berkeley 1993, pp. 41-44.

- ↑ To understand the anecdote, see Enrico Livrea: I γυναικεῖα ῥάκη di Ipazia . In: Eikasmós 6, 1995, pp. 271-273; Danuta Shanzer: Merely a Cynic Gesture? In: Rivista di filologia e di istruzione classica 113, 1985, pp. 61-66. Cf. Christian Lacombrade: Hypatie, un singular "revival" du cynisme . In: Byzantion 65, 1995, pp. 529-531; John M. Rist: Hypatia . In: Phoenix 19, 1965, pp. 214–225, here: 220 f.

- ↑ Synesios, Letter 143, lines 1-52 Garzya; see. letters 137 (lines 41-45) and 142 (lines 7-9). See Antonio Garzya , Denis Roques (ed.): Synésios de Cyrène , Volume 3: Correspondance. Lettres LXIV – CLVI , 2nd edition, Paris 2003, p. 399 note 11–15, p. 400 note 19, p. 408–410 note. 3–19.

- ↑ Michael AB Deakin: Hypatia of Alexandria, Mathematician and Martyr , Amherst (New York) 2007, pp. 104 f., 193 f.

- ↑ See on this question Tassilo Schmitt : The conversion of Synesius of Cyrene , Munich 2001, pp. 278–280 and note 128.

- ↑ On the question of dating, see Pierre Évieux: Introduction . In: Pierre Évieux, William Harris Burns a. a. (Ed.): Cyrille d'Alexandrie, Lettres Festales , Paris 1991, p. 55 f. Note 1; Michael AB Deakin: Hypatia of Alexandria, Mathematician and Martyr , Amherst (New York) 2007, p. 173 f.

- ^ Alan Cameron: Palladas and Christian Polemic . In: The Journal of Roman Studies 55, 1965, pp. 17–30, here: 26–28; Jean Rougé: La politique de Cyrille d'Alexandrie et le meurtre d'Hypatie . In: Cristianesimo nella storia 11, 1990, pp. 485-504, here: 495.

- ↑ Christopher Haas: Alexandria in Late Antiquity. Topography and Social Conflict , Baltimore 1997, pp. 163-165.

- ↑ Socrates of Constantinople, Church History 7:13.

- ↑ John of Nikiu, Chronicle 84.95.

- ↑ Socrates of Constantinople, Church History 7:14. On these events, see Jean Rougé: La politique de Cyrille d'Alexandrie et le meurtre d'Hypatie . In: Cristianesimo nella storia 11, 1990, pp. 485-504, here: 487-495.

- ↑ Socrates of Constantinople, Church History 7:15.

- ↑ Johannes von Nikiu, Chronik 84,100-103.

- ^ Karl Praechter : Hypatia. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IX, 1, Stuttgart 1914, Col. 242-249, here: 247.

- ↑ Christopher Haas: Alexandria in Late Antiquity. Topography and Social Conflict , Baltimore 1997, pp. 314-316.

- ^ Edward J. Watts: Hypatia. Oxford 2017, p. 115 f.

- ^ Henri Dominique Saffrey: Hypatie d'Alexandrie. In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques. Vol. 3, Paris 2000, pp. 814-817, here: p. 816; Alan Cameron, Jacqueline Long: Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius. Berkeley 1993, p. 49 f. For the opposite position see John M. Rist: Hypatia. In: Phoenix 19, 1965, pp. 214-225.

- ^ Henriette Harich-Schwarzbauer: Hypatia. In: Christoph Riedweg u. a. (Ed.): Philosophy of the Imperial Era and Late Antiquity (= Outline of the History of Philosophy. The Philosophy of Antiquity. Volume 5/3), Basel 2018, pp. 1892–1898, here: p. 1896. Cf. Edward J. Watts: Hypatia. Oxford 2017, p. 43.

- ^ Alan Cameron, Jacqueline Long: Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius , Berkeley 1993, p. 44 f .; Michael AB Deakin: Hypatia of Alexandria, Mathematician and Martyr , Amherst (New York) 2007, pp. 96-98.

- ^ For the former, Alan Cameron advocates: Isidore of Miletus and Hypatia: On the Editing of Mathematical Texts . In: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 31, 1990, pp. 103–127, here: 107–115. Disagrees Wilbur Knorr : Textual Studies in Ancient and Medieval Geometry , Boston 1989, pp 755-765.

- ^ Fabio Acerbi: Hypatia . In: Noretta Koertge (Ed.): New Dictionary of Scientific Biography , Volume 3, Detroit u. a. 2008, pp. 435–437, here: 436. For the Diophantos commentary, see Michael AB Deakin: Hypatia and Her Mathematics . In: The American Mathematical Monthly 101, 1994, pp. 234-243, here: 239 f.

- ^ Philostorgios, Church History 8: 9.

- ↑ Historia ecclesiastica tripartita 11.12.

- ↑ Anthologia Palatina 9,400; Translation by Markus Vinzent: "Oxbridge" in the late late antiquity . In: Zeitschrift für antikes Christianentum 4, 2000, pp. 49–82, here: 70.

- ↑ Alan Cameron: The Greek Anthology from Meleager to Planudes , Oxford 1993, pp. 322-324. Maria Dzielska also expressed herself in this sense: Hypatia of Alexandria , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1995, p. 22 f.

- ↑ Enrico Livrea: AP 9.400: iscrizione funeraria di Ipazia? In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 117, 1997, pp. 99-102 ( online ). Also Polymnia Athanassiadi (ed.): Damascius: The Philosophical History , Athens 1999, p. 131 note 96 believes that the verses refer to the philosopher.

- ↑ Kevin Wilkinson: Palladas and the Age of Constantine . In: The Journal of Roman Studies 99, 2009, pp. 36–60, here: 37 f.

- ↑ On the Coptic perspective see Edward Watts: The Murder of Hypatia: Acceptable or Unacceptable Violence? In: Harold Allen Drake (ed.): Violence in Late Antiquity , Aldershot 2006, pp. 333–342, here: 338–342.

- ↑ See Christine Walsh: The Cult of St Katherine of Alexandria in Early Medieval Europe , Aldershot 2007, pp. 3–26.

- ↑ Michael AB Deakin: Hypatia of Alexandria, Mathematician and Martyr , Amherst (New York) 2007, pp. 135 f., 202; Maria Dzielska: Hypatia of Alexandria , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1995, pp. 21 f .; Christian Lacombrade: Hypatia . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Vol. 16, Stuttgart 1994, Sp. 956–967, here: 966; Christine Walsh: The Cult of St Katherine of Alexandria in Early Medieval Europe , Aldershot 2007, p. 10; Gustave Bardy: Catherine d'Alexandrie . In: Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques , vol. 11, Paris 1949, col. 1503–1505, here: 1504.

- ↑ Nikephoros Gregoras, Rhomean History 8.3.

- ^ Thomas Lewis: The History Of Hypatia ... ( online ).

- ^ Christian Lacombrade: Hypatia . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum Volume 16, Stuttgart 1994, Sp. 956–967, here: 958 f., 965.

- ↑ Henriette Harich-Schwarzbauer: Memories of Hypatia of Alexandria . In: Barbara Feichtinger , Georg Wöhrle (Hrsg.): Gender Studies in the Ancient Studies: Possibilities and Limits , Trier 2002, pp. 97-108, here: 98 f.

- ↑ Michael AB Deakin: Hypatia of Alexandria, Mathematician and Martyr , Amherst (New York) 2007, pp. 110-112, 194 f.

- ↑ See Maria Dzielska: Hypatia of Alexandria , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1995, p. 25 f. Richard Hoche already expressed himself in this sense : Hypatia, Theon's daughter . In: Philologus 15, 1860, pp. 435-474, here: 474; he wrote that with Hypatia "the last glory of pagan science was extinguished", that Christian science had not been able to maintain the traditional fame of Alexandria.

- ^ Charles Kingsley: Hypatia, or New Foes with an Old Face ( English text online , German translation online ).

- ↑ See Emilien Lamirande: Hypatie, Synésios et la fin des dieux. L'histoire et la fiction . In: Studies in Religion - Sciences Religieuses 18, 1989, pp. 467–489, here: 478–480.

- ↑ Hans von Schubert: Hypatia of Alexandria in truth and poetry . In: Prussian Yearbooks 124, 1906, pp. 42–60, here: 43.

- ^ Page of the Brooklyn Museum on the artwork.

- ↑ Umberto Eco: Baudolino , Munich 2001 (translation of the Italian original edition from 2000), pp. 475-510, 595 f.

- ^ German website of the film .

- ↑ Hilmar Schmundt (interviewer): "Hypatia is stylized as a victim of Christianity" . In: Spiegel Online , April 25, 2010 (interview with Maria Dzielska).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hypatia |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hypatia of Alexandria |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Greek mathematician, astronomer and philosopher from late antiquity |

| DATE OF BIRTH | at 355 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Alexandria |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 415 or March 416 |

| Place of death | Alexandria |